SYNOPSIS

While about 14% of older Americans are now taking an antidepressant, this broad use of antidepressants has not been associated with a notable decrease in the burden of geriatric depression. This article, based on a selective review of the literature, explores several explanations for this paradox. First, we discuss and reject the possible explanations that antidepressants are not effective in the treatment of depression or that the results of randomized clinical trials are not applicable to the treatment of depression in “real-world” clinical settings. Instead, we propose that the efficacy of antidepressants depends in large part on the way they are used. We present evidence supporting that the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy is associated with better outcomes when it is guided by a treatment algorithm (a “stepped care approach”) as opposed to an attempt to individualize treatment. We review published guidelines and pharmacotherapy algorithms that were developed for the treatment of geriatric depression. Finally, we propose an updated algorithm based on the authors’ interpretation of the available evidence.

Keywords: Major depressive disorder, geriatrics, old age, antidepressant agents, drug therapy, guidelines, algorithm, stepped care

Introduction

About 14% of older Americans are now taking an antidepressant (1,2,3). However, this broad use of antidepressants has not been associated with a notable decrease in the burden of geriatric depression (4,5)). This article, based on a selective review of the literature, explores several explanations for this paradox. First, we discuss and reject the possible explanations that antidepressants are not effective in the treatment of depression or that the results of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are not applicable to the treatment of depression in “real-world” clinical settings. Instead, we propose that the efficacy of antidepressants depends in large part on the way they are used. We present evidence supporting that the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy is associated with better outcomes when it is guided by a treatment algorithm (a “stepped care approach”) as opposed to an attempt to individualize treatment. We review published guidelines and pharmacotherapy algorithms that were developed for the treatment of geriatric depression. Finally, we propose an updated algorithm based on the authors’ interpretation of the available evidence.

Are Antidepressants Effective for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder?

Some authors have proposed that antidepressants are either not effective or only minimally effective except in patients with the most severe depression, pointing out the small effect sizes in meta-analyses including both published and unpublished placebo-controlled randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of antidepressants (e.g., 6,7,8). Several analyses have been published specifically to refute these results (e.g., 9,10,11, 12 (12- Gibbons et al, 2012) or to show that psychotropic medications (including antidepressants) are as efficacious as drugs used to treat general medical conditions (13)Leucht et al, 2012. The debate about the true efficacy of antidepressants (i.e., whether there is a meaningful difference in the remission or response rates experienced by patients randomized to an antidepressant or a placebo) continues (14); (15); (16). Regardless of the degree to which antidepressants are more efficacious than placebo, patients treated with active antidepressants should experience at least the improvement associated with the use of a placebo. However, some published data suggest that patients whose depression is treated under usual care (non-study) conditions are actually less likely to respond to antidepressant treatment or experience a remission of their depressive symptoms than depressed patients who receive a placebo in a RCT. Poor outcomes of depressed patients treated under usual care conditions have been reported both in patients treated by primary care providers (PCP) and in those treated by psychiatrists. For instance, (17) reported that only 30% of adult patients with a major depressive disorder (MDD) who were treated by a psychiatrist experienced remission of their major depressive episode after 3 months, a rate that is lower than the 30-40% rate of remission typically associated with placebo in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adults with MDD (12. (Gibbons et al, 2012); (13)

Are the Results of Randomized Controlled Trials of Antidepressants Applicable to “Real-World” Geriatric Practice?

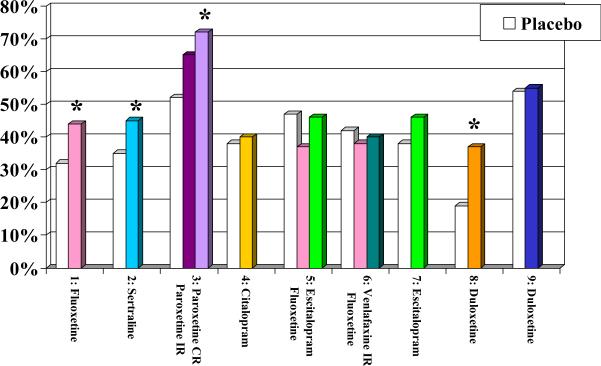

Some authors have proposed that antidepressants are not as effective in clinical practice as in RCTs because patients who participate in RCTs are not representative of patients who are treated in “real-world” clinical practice. This argument is supported by some published data showing that, due to the required eligibility criteria they have to meet to participate, depressed subjects included in RCTs differ from the population from which they are drawn (18) (19). However, the gap between the efficacy of antidepressants when used in an RCT and their lower effectiveness when used under usual care conditions persists in studies that randomize depressed participants who meet the same eligibility criteria to an experimental intervention or to usual care. For instance, in two large geriatric studies --IMPACT ((20) (21) and PROSPECT (22 Mulsant et al, 2001) (23) (24) (25); -- older depressed participants who met the same eligibility criteria were randomized to either an experimental intervention or treatment as usual. In these two studies, the response rates associated with usual care (IMPACT: 16% after 12 months; PROSPECT: 19% after 4 months -- see Table 1) were less than half the response rates associated with placebo (mean + SD: 40 + 10%; median: 38%; range: 19-54% -- see Figure 1A) in the nine published placebo-controlled RCTs that have assessed the efficacy of second-generation antidepressants in older patients with MDD (26); (27); (28); (29); (30); (31); (32) (33) (34)

Table 1.

Outcomes in Two Randomized Studies Comparing an Stepped—Care Approach vs. Treatment-As-Usual for the Treatment of Late-Life Depression

| Study | N | Treatment algorithm | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMPACT (Unutzer et al, 2001; Unutzer et al, 2002) | 1801 | Step 1: AD (typically a SSRI) or PST (8-12 weeks) Step 2: -Non-response: Switch to other AD or PST -Partial response: Combine with other AD or PST Step 3: -Combine AD and PST -Consider ECT or other specialty services |

Rate of response (50% reduction in depression score) after 12 months: Intervention: 45% Usual care: 19% |

| PROSPECT (Mulsant et al, 2001; Bruce et al, 2004; Alexopoulos et al, 2005; Alexopoulos et al, 2009) | 599 | Step 1: Optimize current AD (if applicable) Non-response - Switch to: Step 2: citalopram 30 mg once a day Step 3: bupropion SR 100-200 mg twice a day Step 4: venlafaxine XR 150-300 mg once in AM Step 5: nortriptyline (target 80-120 ng/ml) Step 6: mirtazapine 30-45 mg in the evening Partial response – Add: Step 2: bupropion SR 100-200 mg twice a day Step 3: nortriptyline (target 80-120 ng/ml) Step 4: lithium (target 0.60-0.80 mEq/l) Then, steps 2, 4, 6 for non-responders Also, IPT can be used as an alternative to AD or as an augmentation to AD. |

Rate of response (HDRS score of 10 or below) - After 4 months: Intervention: 33% Usual care: 16% - After 12 months: Intervention: 54% Usual care: 45% |

AD: antidepressant; ECT: electro-convulsive therapy; IPT: interpersonal therapy; HDRS: Hamilton depression rating scale; PST: problem-solving therapy; SSRI: selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitor

The process of care in the experimental intervention group in IMPACT and PROSPECT or in other RCTS is very different from the process of usual care in primary care or psychiatric practice (see Table 2). Several lines of evidence suggest that the differences in outcomes are due to these differences in the process of care. For example, a meta-analysis has shown that in placebo-controlled RCTs of antidepressants for adult MDD lasting 6 weeks, two additional follow-up visits at week 3 and week 5 improve outcomes of both placebo and of active antidepressants, accounting for 41% of the improvement observed with placebo and 27% for the improvement with an antidepressant (35). The effect of additional visits was cumulative and proportional (i.e., two extra visits yielded twice the benefits of one additional visits) and it was not due to a lower likelihood of dropping out (i.e., the drop-outs rates were similar with 4, 5, or 6 follow-up visits) (35).

Table 2.

Processes of Care When Using Antidepressants Under Experimental Conditions vs. Usual Care Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Usual Care Condition | |

|---|---|---|

| Schedule of visits | Fixed; 4-6 visits over 6 weeks; 6-12 visits over 8-12 weeks. | Based on physician's and patient's availability; 2-3 visits over 12 weeks |

| Duration of visits | 30-60 minutes. | 10-20 minutes. |

| Treatment protocol | Predetermined; minimal adaptations based on patient's characteristics (e.g., slower titration for frail patients). | Individualized for each patient based on their characteristics and preferences. |

| Selection of antidepressant | Small number of antidepressants preselected based on best evidence or guidelines and used in all patients. | Large number of antidepressants, each used in a small number of patients; matching patient's clinical characteristics with perceived features of specific antidepressants. |

| Dose titration and change in treatment | Predetermined; based on operationalized criteria, protecting clinicians from personal biases or pressures from patients or their families. | Negotiated at each visit with each patient based on perceived adverse effects or lack of improvement. Changes often ill-advised or ill-timed. |

| Monitoring of symptoms and adverse effects | Systematic monitoring with use of structured interviews and validated scales. | Monitoring based on spontaneous reports and ad-hoc clinical interviews. |

| Main focus of clinical interactions | Maximizing treatment adherence with psychoeducation, characterization of changes in patient's symptoms, management of adverse effects. | Negotiating whether and how antidepressants should be used, titrated up or down, switched, or augmented; selection of augmenting or alternative agents. |

Besides the frequency, duration, and quality of follow-up visits, RCTs and usual care also differ in the quantity and quality of the antidepressant pharmacotherapy offered. In PROSPECT, older patients were systematically screened for the presence of depression and the PCPs were notified when their patients were found to suffer from a clinically significant depression requiring treatment. Still, when assessed after 4, 8, 12, 18, or 24 months, only 50-60% of the patients randomized to usual care were found to be receiving any treatment for depression (25). These low rates of initiation, continuation, and maintenance of treatment in the older participants of PROSPECT are consistent with the low rates reported in both older (36 Kessler et al, 2009) and younger ((17); (4) adults. By contrast, 80-90% of the PROSPECT patients randomized to the intervention were receiving some treatment for depression when assessed after 4, 8, 12, 18, or 24 months (25).

How Should Clinicians Select Antidepressants to Treat their Older Patients?

To make matters worse, barely half of adults who receive depression treatment under usual care receive minimally adequate treatment ((17); (4). Again, the low level of the quality of antidepressant pharmacotherapy under usual care is attributable in large part to issues related to the process of care, in particular the way clinicians select antidepressants (see Table 2). For instance, despite evidence showing that all antidepressants have comparable efficacy or effectiveness in the acute, continuation, or maintenance treatment of MDD (37), a majority of physicians try to match each individual patient to a specific antidepressant. The limited empirical data on which strategy physicians use to match patients to antidepressants suggest that they consider three main factors: presence of specific “target” symptoms --in particular, insomnia, anxiety, fatigue, or appetite changes; presence of comorbid conditions --in particular panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or post-traumatic disorder; or avoidance of specific side effects --in particular, sexual dysfunction, weight gain, fatigue, anticholinergic effects, or agitation (38).

Avoidance of specific adverse effects makes sense and it is endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with MDD (39). However, there is no convincing evidence that any selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) is superior to other SSRIs or SNRIs in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Similarly, trying to target specific depressive symptoms based on the distinct side-effect profiles of various antidepressants appears to be a futile pursuit given that response to specific medications is not predicted by specific symptoms or symptom clusters (40); (41); (42). For instance, an analysis assessed whether a “sedating antidepressant” (imipramine) would be better tolerated or more efficacious than an “activating antidepressant” (fluoxetine) in 355 depressed patients enrolled in an RCT who presented with insomnia (43) (Simon et al, 1998). During four weeks of treatment, patients were significantly more likely to discontinue imipramine than fluoxetine, regardless of whether they had a low or high level of insomnia; after four weeks, the remission rates for those with a high level of insomnia were 16% with imipramine vs. 21% with fluoxetine (and 23% vs. 38% for those with low level of insomnia); there was no significant interaction between level of insomnia and treatment group for either discontinuation rates or remission rates (43).

Minimal empirical data are available to assess other strategies used by physicians to individualize treatment for depression. In a RCT for chronic depression, initial preference for pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy was a strong predictor of treatment outcome following randomization to pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy (but, surprisingly, not of the likelihood of dropping out) (44). In a 20-year old retrospective chart review, 20/35 (57%) patients responded to an antidepressant to which they had responded previously, while 19/24 (79%) were treated with a different antidepressant and responded (45). To our knowledge, there are no other published data to support or contradict the wisdom of heeding a depressed patient's preference for a specific treatment or of favoring an antidepressant to which a patient has responded in the past (40) (Simon & Perlis, 2010).

Most clinicians are surprised when they hear that individualized interventions under usual care conditions (i.e., selection of a specific antidepressant based on a patient's unique characteristics and treatment management based on patient's unique experience) yield significantly worse outcomes than a systematic approach used under experimental conditions (i.e., all patients receiving a preselected antidepressant and treatment changes guided by predetermined criteria). However, for the treatment of geriatric depression, the benefits of using a stepped-care approach built around a treatment algorithm are supported not only by the results of IMPACT ((20, 21)Unutzer et al, 2001; Unutzer et al, 2002) and PROSPECT (22) Mulsant et al, 2001; (23) Bruce et al, 2004; (24) Alexopoulos et al, 2005; (25) Alexopoulos et al, 2009) but also by four other studies showing that about 80% of older patients with MDD seen in psychiatric settings can respond to such an approach (46); (47) Whyte et al, 2004; (48); (49).

What Can we Learn from Guidelines for the Pharmacotherapy of Geriatric Depression?

Taken together, the data discussed above suggest that clinicians could double the treatment response rates experienced by their older depressed patients if they adopted a more systematic approach to treatment. Treatment guidelines summarizing and interpreting the relevant evidence and expert opinion offer a starting point to clinicians who want to follow such an approach. To our knowledge, the most recent guidelines for the pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression were published in 2006 (50); (51). The recommendations from these Canadian guidelines and from earlier US expert consensus guidelines (52) are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Recommendations for the Pharmacotherapy of Major Depression from the 2001 US expert consensus guidelines (53) (50) (51)

| 2001 US Expert Consensus Guidelines | 2006 Canadian Guidelines | |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred treatment | An antidepressant (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] or venlafaxine XR preferred) plus psychotherapy. | An antidepressant, psychotherapy, or a combination of both if the depression is of mild or moderate severity; a combination of an antidepressant and psychotherapy for severe depressions. |

| Specific antidepressant | Citalopram and sertraline are preferred with paroxetine as another first-line option. | Citalopram, sertraline, venlafaxine, bupropion or mirtazapine. |

| Starting dose | Begin with “somewhat lower doses” than in younger adults. | Half of the recommended dose for younger adults. |

| Increases in dose | Wait 2-4 weeks before increasing a low dose if there is little or no response and 3-5 weeks if there is a partial response. | Aim for “an average dose” within one month if the medication is well tolerated. In the absence of improvement after at least 2 weeks on “an average dose”, increase dose gradually (up to maximum recommended dose) until clinical improvement or, limiting side effects are observed. |

| When to change treatment | After 3-6 weeks at a “therapeutic” or the maximum tolerated dose” if there is little or no response and 4-7 weeks if there is a partial response. | After at least 4 weeks at the maximum tolerated or recommended dose if there is no or minimal response after 4-8 weeks if there is some partial response. |

| What to do in case of minimal or no response to initial antidepressant | Preferred option: switch to venlafaxine or bupropion. Alternative option: switch to nortriptyline, mirtazapine, or another SSRI | Consider “all reasonable treatment options” including ECT, combination of antidepressants or mood stabilizers, addition of psychotherapy |

| What to do in case of partial response to initial antidepressant | Combine or augment initial antidepressant with another agent | Switch to another antidepressant of the same or another class while considering the risk of losing the improvements made with the first treatment |

| Agents to consider for combination or augmentation | Bupropion, lithium, or nortriptyline | Mirtazapine, bupropion, or lithium |

SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

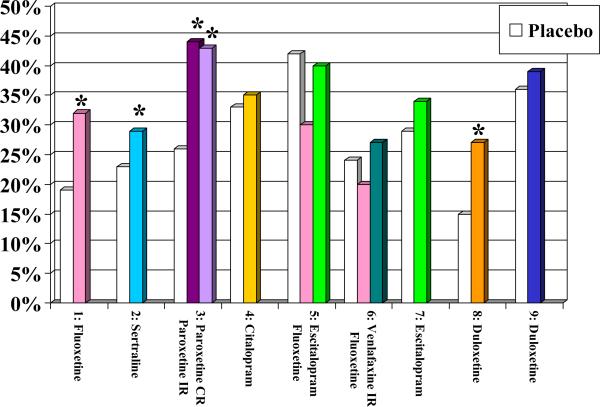

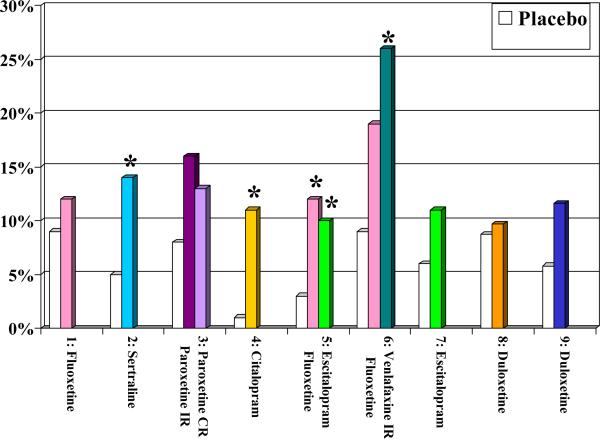

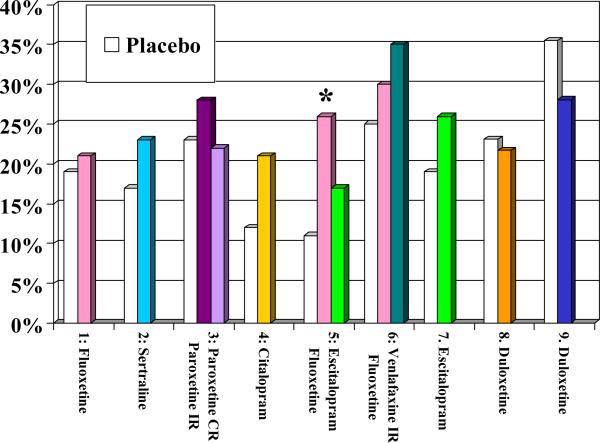

Overall, the recommendations from these two guidelines are consistent. One could argue that while they are informed by evidence, they reflect more the preference of the experts involved in their creation than the direct results of RCTs. As of April 2014, we know of nine published placebo-controlled trials of the efficacy and tolerability of SSRIs or SNRIs in the acute treatment of older patients with MDD ((26) Tollefson et al, 1995; (27)Schneider et al, 2003; (28) Rapaport et al, 2003; (29)Roose et al, 2004; (30)Kasper et al, 2005; (31)Schatzberg & Roose, 2006; (32) Bose et al, 2008; (33) Raskin et al, 2007; (34) Robinson et al, 2014). Figure 1 displays the response rates, remission rates, drop-out rates attributed to adverse effects, and overall drop out rates in these nine RCTs. Fluoxetine (in one of three trials), sertraline (in one trial), paroxetine (in one trial), and duloxetine (in one of two trials) were more efficacious than placebo; by contrast, the unique placebo-controlled trial that has assessed the efficacy of citalopram and the two placebo-controlled trials that have assessed the efficacy of its S-enantiomer, escitalopram, have failed to demonstrate their superiority to placebo (see Figure 1A & 1B). Still, in both the US and Canadian guidelines, citalopram was recommended as a first-line treatment. Experts – including some of the authors of this paper (22) Mulsant et al, 2001)– have typically attributed their preference for citalopram to its lack of drug-drug interaction and its good tolerability “in their clinical experience.” However, in placebo-controlled trials, all SSRIs except for paroxetine were associated with significantly higher rates of discontinuation attributed to adverse effects than placebo (see Figure 1C) and only fluoxetine (in one of three trials) was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of overall premature discontinuation (i.e., discontinuation for any reason) than placebo (see Figure 1D). The Canadian guidelines also recommend the use of bupropion, mirtazapine or venlafaxine as first-line treatment and both the US and Canadian guidelines recommend the use of bupropion or venlafaxine as second-line treatment. Neither bupropion nor mirtazapine has been assessed in a published placebo-controlled trial in older patients with major depressive disorder, and the two trials that have assessed the efficacy of venlafaxine as a first-line treatment have failed to demonstrate its superiority to placebo. However, in two small non-blinded studies, 14/27 (52%) older patients responded to a switch to venlafaxine after having failed to respond to 1-3 other antidepressants (47) (Whyte et al, 2004; (53) Mazeh et al, 2007)

Figure 1A.

Response Rates in Nine Published Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials of Newer Antidepressants

Figure 1B.

Remission Rates in Nine Published Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials of Newer Antidepressants

Figure 1C.

Discontinuation Rates Attributed to Adverse Effects in Nine Published Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials of Newer Antidepressants

Figure 1D.

Overall Discontinuation Rates Published in Nine Published Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials of Newer Antidepressants

* significant difference between antidepressant and placebo

An Updated Algorithm for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Geriatric Depression

Beyond the two questions of which antidepressant to use and at what dose, there is a paucity of data in adult depressed patients (54); (55); (56); (57); (58); (59); (60) and almost none in older patients (47) (Whyte et al, 2004; (61); (62) ; (63) that directly address the practical questions faced by clinicians when they treat an actual patient, such as: how long should one wait before making a change in treatment? When is it preferable to substitute another antidepressant or to add a second antidepressant or another psychotropic agent ? Which specific antidepressant should one substitute? Which psychotropic agent should one add? Mindful of these limitations in the literature, the five authors convened during a workshop held in September 2013 at the annual meeting of the Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry to discuss what changes, if any, they would consider to the recommendations from the 2001 US or 2006 Canadian guidelines and to the published algorithms discussed above, if they had to propose an updated algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression? While guidelines tend to list several recommended alternatives, treatment algorithms are typically more prescriptive, focusing on a series of well-defined steps (see Table 1). Thus the authors tried to arrive at a consensus on what would constitute the preferred steps when treating older patients presenting with non-bipolar non-psychotic MDD. However, they did not reach a unanimous endorsement for any steps; Table 4 presents the preferred choice of the majority with the alternative(s) endorsed by the minority.

Table 4.

Updated Pharmacotherapy Algorithm for the Treatment of Late-Life Depression

| Majority consensus and minority alternative | |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Escitalopram Alternatives: sertraline, duloxetine |

| Step 2 for minimal or non-response) | Switch to duloxetine Alternatives: venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine |

| Step 3 for minimal or non-response | Switch to nortriptyline Alternative: bupropion |

| Step 2-3 for partial response | Augment antidepressant with lithium or an atypical antipsychotic Alternatives: combine SSRI or SNRI with mirtazapine or bupropion |

| Duration of each step | 6 weeks Alternatives: 4 weeks; 8 weeks |

SSRI: selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

While older depressed patients typically present with comorbid physical conditions and some cognitive impairment, the proposed steps were not tailored for specific comorbid conditions (e.g., Parkinson's disease, dementia, or chronic pain). Given the availability of older published guidelines and algorithms, the authors considered the newer antidepressants available (e.g., escitalopram, duloxetine), recent safety data (e.g., the data and warnings about the possible cardiovascular effects of citalopram), and newer data and indications for the use of atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, quetiapine) in the treatment of MDD. However, the authors reaffirmed their agreement with principles of judicious prescribing –including initiating only one medication at a time; avoiding premature changes; and being circumspect about new medications for which rare adverse effects may not have been recognized yet (64) -- leading them to favor simpler steps (e.g., one medication rather than two) and safer steps (e.g., medications less likely to be involved in drug-drug interactions or medications less likely to be associated with serious adverse events). Finally, while the authors acknowledge a role for both psychotherapy (e.g., (65) Reynolds et al, 2010) and brain stimulation (66Dombrovski & Mulsant, 2007); (67) in the treatment of geriatric depression, this algorithm focuses on pharmacologic agents. Similarly, while they acknowledge the crucial role of long-term continuation and maintenance pharmacotherapy for the prevention of relapse and recurrence of geriatric depression (68), the proposed algorithm focuses on the use of antidepressant during the acute phase of treatment.

First-Line Antidepressant

Despite two negative geriatric placebo-controlled RCTs (see Figure 1), our updated algorithm recommends escitalopram as the preferred first-line agent (with sertraline and duloxetine as alternatives). The change from citalopram – recommended in the 2001 US and 2006 Canadian guidelines-- reflects the warning from the US Food and Drug administration that citalopram has now been associated with a dose-dependent QT interval prolongation (which can cause torsade de pointes, ventricular tachycardia, or sudden death) and the related maximum recommended dose of 20 mg per day for patients older than 60 years of age (69). Some may argue that this warning is more a medico-legal concern than a clinical concern given the lack of cardiotoxocity associated with higher doses of citalopram in a pharmacoepidemiology study of more than 600,000 mid-life and late-life patients (70) . However, the significant lengthening of QTc in a recent placebo-controlled trial involving 186 older patients with dementia (71) is a reminder that, when assessing causal relationships, RCTs cannot be replaced by analyses of non-randomized observational data, even when they attempt to control for a large number of potential confounders (72) (Mulsant, 2014).

Second Step Treatment for Non-Responders

The selection of duloxetine as the preferred second-line agent (with venlafaxine or desvenlafaxine as alternatives) for older patients who fail to improve significantly on escitalopram is congruent with the 2001 US guidelines recommending to switch to an antidepressant from another class when a patient fails to respond to an SSRI (see Table 3). This preference for switching antidepressant classes is not supported by STAR*D, in which adult patients whose treatment was switched from citalopram to bupropion, sertraline, or venlafaxine did not differ significantly with respect to outcomes, tolerability, or adverse events (56) (59) (Rush et al, 2006, 2008). While there is no geriatric study similar to STAR*D, as discussed above, the efficacy of venlafaxine in older patients who failed to respond to a SSRI is supported by two small studies (47) (Whyte et al, 2004; (53) Mazeh et al, 2007). While we are not aware of similar geriatric data for duloxetine, its efficacy is supported by one of two published placebo-controlled RCTs (33) Raskin et al, 2007); also, in these two placebo-controlled trials (33) Raskin et al, 2007; (34) Robinson et al, 2014), duloxetine and placebo had similar discontinuation rates attributed to adverse effects. By contrast, in a single placebo-controlled RCT (31)Schatzberg & Roose, 2006), the efficacy of venlafaxine IR was not different from placebo, while its discontinuation rate attributed to adverse effects was higher than with placebo (see Figure 1).

Duloxetine was also favored over venlafaxine because of its indication not only for MDD and generalized anxiety disorder but also for the management of several pain syndromes that are quite common in older depressed patients: neuropathic pain associated with diabetes, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain (73) . However, these potential advantages of duloxetine are not supported by the much larger number of RCTs conducted in younger patients with MDD: in two recent meta-analyses that compared the results of RCTs of duloxetine and other antidepressants in adults patients with MDD duloxetine was not more efficacious than SSRIs or venlafaxine but it was associated with a higher drop-out rate than escitalopram or venlafaxine (74); (75) . Similarly, in a pooled analysis of four head-to-head RCTs in adult patients with MDD, the effect of duloxetine or paroxetine on pain did not differ significantly (42) .

Third Step Treatment for Non-Responders

When older patients have failed an SSRI and an SNRI, our algorithm recommends the use of nortriptyline (with bupropion as an alternative). Again, preference is given to a switch to an antidepressant of a different class as opposed to augmenting or combining the failed antidepressant. The evidence that two psychotropic agents are more efficacious than one is relatively strong in younger patients (76) but much less so in older adults (61) in whom polypharmacy causes more adverse events than monotherapy (47) . The choice of a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) is supported by several geriatric RCTs that established their efficacy and safety in the 1980's and 1990's (77) . Similarly, the choice of nortriptyline among the TCAs is justified both by available RCTs and by data showing that it is less likely to cause orthostatic hypotension, falls, or anticholinergic side effects than tertiary amine TCAs (i.e., amitriptyline, clomipramine, doxepin, and imipramine) (78 Chew et al, 2008); (79). However, contrary to the widespread belief of many experienced psychiatrists, there is no convincing evidence that TCAs are more efficacious than SSRIs, but there is strong evidence than SSRIs are better tolerated, in particular by older patients (80) ; (81); (82); (83) .

Second or Third Step Treatment for Partial Responders

For patients who have experienced a partial response to a first or second line antidepressant (typically, a SSRI or a SNRI), the updated algorithm recommends augmenting the antidepressant with lithium or an atypical antipsychotic (or, alternatively, combining it with mirtazapine or bupropion). The preference for an augmentation (or combination) strategy over switching to another agent is consistent with the 2001 US guidelines and with the caution in the 2006 Canadian guidelines that a partial improvement may be lost during a switch of medications. While the use of lithium as an augmenting agent is supported by a larger number of geriatric studies than is the use of an atypical antipsychotic (84) (61) (85) Steffens et al, 2011), drug titration and ongoing monitoring of an atypical antipsychotic are easier to implement. In terms of selecting a specific atypical antipsychotic, the use of aripiprazole as an augmenting agent in older patients with MDD who had failed to respond to an antidepressant is supported by a small open study in 24 older patients (remission rate: 50%) (84) (Sheffrin et al, 2009) and a secondary analysis of 409 subjects aged 50-67 years who had participated in three different placebo-controlled RCTs (remission rates: 33% vs. 17% with placebo) (85) . The use of quetiapine is supported by a placebo-controlled RCT in which 338 older patients with MDD had higher remission and response rates which quetiapine monotherapy (50-300 mg/day) than with placebo (remission rates: 56% vs. 23%; response rates: 64% vs. 30%) (86). In these trials, aripiprazole and quetiapine were well tolerated (akathisia was the most common adverse effect with aripiprazole and somnolence with quetiapine) but clinicians need to remain mindful of the incontrovertible risk of increased mortality risk associated with atypical antipsychotics in late life (74).

Conclusion

More than 60 years after their introduction into clinical practice, antidepressants remain the mainstay of the treatment of depression in older adults. Their continuing use is supported by solid evidence. However, the typical outcomes of antidepressant treatment under usual care conditions are mediocre at best. Following a systematic approach to their use can improve these outcomes. At its core, such a systematic approach requires a treatment algorithm. However, most published RCTs of the pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression assess only one treatment step, typically the first, or, more rarely, the second. Thus, given our current state of knowledge, treatment algorithms for the pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression can be informed by evidence, but are not yet truly evidence-based.

KEY POINTS.

The efficacy of antidepressants depends in large part on the way they are used. Under usual care conditions, the outcomes of antidepressant pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression have been shown to be mediocre at best.

Trying to individualize treatment by matching each patient with a specific antidepressant based on the patient's symptoms and an antidepressant putative side-effect profile is ineffective. Instead, the outcomes of antidepressant pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression can be improved markedly when antidepressants are prescribed following an algorithmic (“stepped-care”).

Published guidelines and algorithms for the antidepressant pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression are informed by published evidence but they do not conform to this evidence. This article presents an updated algorithm for the antidepressant pharmacotherapy of geriatric depression that is based on the authors’ interpretation of the available evidence.

Data From: 1. Tollefson et al, 1995; 2. Schneider et al, 2003; 3. Rapaport et al, 2003; 4. Roose et al, 2004; 5. Kasper et al, 2005; 6. Schatzberg & Roose, 2006; 7. Bose et al, 2008; 8. Raskin et al, 2007; 9. Robinson et al, 2014.

1. Tollefson GD, Bosomworth JC, Heiligenstein JH, Potvin JH, Holman S. A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine in geriatric patients with major depression. The Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995; 7(1):89-104.

2. Schneider LS, Nelson JC, Clary CM, Newhouse P, Krishnan KR, Shiovitz T, Weihs K, Sertraline Elderly Depression Study Group. An 8-week multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in elderly outpatients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160(7):1277-85.

3. Rapaport MH, Schneider LS, Dunner DL, Davies JT, Pitts CD. Efficacy of controlled-release paroxetine in the treatment of late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003; 64(9):1065-74.

4. Roose SP, Sackeim HA, Krishnan KR, Pollock BG, Alexopoulos G, Lavretsky H, Katz IR, Hakkarainen H, Old-Old Depression Study Group. Antidepressant pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression in the very old: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161(11):2050-9.

5. Kasper Kasper S, de Swart H, Friis Andersen H. Escitalopram in the treatment of depressed elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005; 13(10):884-91

6. Schatzberg A, Roose S. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in geriatric outpatients with major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006; 14(4):361-70.

7. Bose A, Li D, Gandhi C. Escitalopram in the acute treatment of depressed patients aged 60 years or older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008; 16(1):14-20.

8. Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, Sheikh J, Xu J, Dinkel JJ, Rotz BT, Mohs RC. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007; 164(6):900-9.

9. Robinson M, Oakes TM, Raskin J, Liu P, Shoemaker S, Nelson JC. Acute and long-term treatment of late-life major depressive disorder: duloxetine versus placebo. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014; 22(1):34-45.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURES

Funding sources:

This work was supported in part by grant MH083643 from the US National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Mulsant currently receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the US National Institute of Health (NIH), Bristol-Myers Squibb (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial) and Pfizer (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial). Within the past three years he has received research support from Eli-Lilly (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial). He directly owns stocks of General Electric (less than $5,000).

Dr. Blumberger currently receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the US National Institute of Health (NIH). He receives research support and in-kind equipment support from Brainsway Ltd for an investigator-initiated clinical trial and a sponsor-initiated clinical trial. He receives in-kind equipment support from Tonika-Magventure for an investigator-initiated study.

Dr. Ismail has served as a consultant to Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli-Lilly, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer and Sunovion.

Dr. Rabheru receives compensation from the Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario. He receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Dr. Rapoport receives research funding from the Canadian Institute for Health Research and from the Ontario Ministry of Transportation.

References

- 1.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):848–56. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant Use in Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief; No. 76. 2011 Oct; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db76.pdf Accessed on April 12, 2014. [PubMed]

- 3.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in long-term use of antidepressant medications: results from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(2):169–77. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V. Age differences in major depression: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):225–37. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirsch I. The Emperor's New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth. The Bodley Head; London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;12(1):47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fountoulakis KN, Moller HJ. Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re interpretation of the Kirsch data. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;12(3):405–412. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vöhringer PA, Ghaemi SN. Solving the antidepressant efficacy question: effect sizes in major depressive disorder. Clin Ther. 2011;(12):B49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thase ME, Larsen KG, Kennedy SH. Assessing the ‘true’ effect of active antidepressant therapy v. placebo in major depressive disorder: use of a mixture model. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;12:501–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons, et al. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leucht S, Hierl S, Kissling W, et al. Putting the efficacy of psychiatric and general medicine medication into perspective: review of meta-analyses. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:97–106. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;12(4):851–864. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huedo-Medina T, Johnson B, Kirsch I, Kirsch, et al. calculations are correct: reconsidering Fountoulakis & Moller's re-analysis of the Kirsch data. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012. 2008;12:1193–1198. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fountoulakis KN, Veroniki AA, Siamouli M, Möller HJ. No role for initial severity on the efficacy of antidepressants: results of a multi-meta-analysis. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyers BS, Sirey JA, Bruce M, Hamilton M, Raue P, Friedman SJ, Rickey C, Kakuma T, Carroll MK, Kiosses D, Alexopoulos G. Predictors from early recovery from major depression among people admitted to community-based clinics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:729–735. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI, Posternak MA. Are subjects in pharmacological treatment trials of depression representative of patients in routine clinical practice? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):469–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Posternak MA. Generalizability of antidepressant efficacy trials: differences between depressed psychiatric outpatients who would or would not qualify for an efficacy trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 b;162(7):1370–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JW, Jr, Callahan CM, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, Hoffing M, Arean P, Hegel MT, Schoenbaum M, Oishi SM, Langston CA. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care. 2001;39(8):785–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, Hoffing M, Arean P, Hegel MT, Schoenbaum M, Oishi SM, Langston CA. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulsant, et al. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Bruce ML, Moonseong H, Ten Have T, Raue P, Bogner H, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF. Remission in depressed geriatric primary care patients: a report from the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:718–724. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexopoulos G, Reynolds C, Bruce M, Katz I, Raue P, Mulsant B, Oslin D, Ten Have T, the PROSPECT Group Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):882–890. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tollefson GD, Bosomworth JC, Heiligenstein JH, Potvin JH, Holman S. A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine in geriatric patients with major depression. The Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7(1):89–104. doi: 10.1017/s1041610295001888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider LS, Nelson JC, Clary CM, Newhouse P, Krishnan KR, Shiovitz T, Weihs K. Sertraline Elderly Depression Study Group. An 8-week multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in elderly outpatients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1277–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rapaport MH, Schneider LS, Dunner DL, Davies JT, Pitts CD. Efficacy of controlled-release paroxetine in the treatment of late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(9):1065–74. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roose SP, Sackeim HA, Krishnan KR, Pollock BG, Alexopoulos G, Lavretsky H, Katz IR, Hakkarainen H, Old-Old Depression Study Group Antidepressant pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression in the very old: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):2050–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasper Kasper S, de Swart H, Friis Andersen H. Escitalopram in the treatment of depressed elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(10):884–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schatzberg A, Roose S. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in geriatric outpatients with major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(4):361–70. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194645.70869.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bose A, Li D, Gandhi C. Escitalopram in the acute treatment of depressed patients aged 60 years or older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181591c09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, Sheikh J, Xu J, Dinkel JJ, Rotz BT, Mohs RC. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):900–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson M, Oakes TM, Raskin J, Liu P, Shoemaker S, Nelson JC. Acute and long-term treatment of late-life major depressive disorder: duloxetine versus placebo. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Therapeutic effect of follow-up assessments on antidepressant and placebo response rates in antidepressant efficacy trials: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007:190287–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.028555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler, et al. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:772–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmerman M, Posternak M, Friedman M, Attiullah N, Baymiller S, Boland R, Berlowitz S, Rahman S, Uy K, Singer S. Which factors influence psychiatrists' selection of antidepressants?. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1285–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 2010 Revision. http://psychiatryonline.org/content.aspx?bookID=28§ionID=1667485#654274 Accessed on line: April 13, 2014.

- 40.Simon GE, Perlis RH. Personalized medicine for depression: can we match patients with treatments? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1445–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gartlehner G, Thaler K, Hill S, Hansen RA. How should primary care doctors select which antidepressants to administer? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(4):360–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thaler KJ, Morgan LC, Van Noord M, Gaynes BN, Hansen RA, Lux LJ, Krebs EE, Lohr KN, Gartlehner G. Comparative effectiveness of second-generation antidepressants for accompanying anxiety, insomnia, and pain in depressed patients: a systematic review. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(6):495–505. doi: 10.1002/da.21951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon GE, Heiligenstein JH, Grothaus L, Katon W, Revicki D. Should anxiety and insomnia influence antidepressant selection: a randomized comparison of fluoxetine and imipramine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):49–55. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Markowitz JC, Manber R, Arnow B, Klein DN, Thase ME. Patient preference as a moderator of outcome for chronic forms of major depressive disorder treated with nefazodone, cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, or their combination. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(3):354–61. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Remillard A, Blackshaw S, Dangor A. Differential responses to a single antidepressant in recurrent episodes of major depression. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:359–61. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steffens DC, McQuoid DR, Krishnan KRR. The Duke Somatic Treatment Algorithm for Geriatric Depression (STAGED) Approach. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36(2):58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whyte EM, Basinski J, Farhi P, Dew MA, Begley A, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF. Geriatric depression treatment in nonresponders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12):1634–41. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kok RM, Nolen WA, Heeren TJ. Outcome of late-life depression after 3 years of sequential treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. Apr. 2009;119(4):274–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribeiz S, Avila R, Martins CB, Moscoso MA, Steffens DC, Bottino CM. Validation of a treatment algorithm for major depression in older Brazilian sample. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(6):647–653. doi: 10.1002/gps.3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buchanan D, Tourigny-Rivard MF, Cappeliez P, Frank C, Janikowski P, Spanjevic L, Malach FM, Mokry J, Flint A, Herrmann N. National Guidelines for Seniors’ Mental Health: The Assessment and Treatment of Depression. Can J Geriatr. 2006;9(Suppl 2):S52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canadian Coalition for Senior's Mental Health National Guidelines for Seniors’ Mental Health -- The Assessment and Treatment of Depression. 2006 Available at: http://www.ccsmh.ca/en/projects/depression.cfm. Accessed April 5, 2014.

- 52.Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Carpenter D, Docherty JP, Ross RW. Pharmacotherapy of depression in older patients: a summary of the expert consensus guidelines. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2001;7(6):361–376. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazeh D, Shahal B, Aviv A, Zemishlani H, Barak Y. A randomized single-blind comparison of venlafaxine with paroxetine in elderly patients suffering from resistant depression. Int ClinPsychopharmacol. 2007;22:371–375. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32817396ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fava M, Alpert J, Nierenberg A, Lagomasino I, Sonawalla S, Tedlow J, Worthington J, Baer L, Rosenbaum JF. Double-blind study of high-dose fluoxetine versus lithium or desipramine augmentation of fluoxetine in partial responders and nonresponders to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(4):379–87. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quitkin FM, Petkova E, McGrath PJ, Taylor B, Beasley C, Stewart J, Amsterdam J, Fava M, Rosenbaum J, Reimherr F, Fawcett J, Chen Y, Klein D. When should a trial of fluoxetine for major depression be declared failed?. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):734–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rush A, Trivedi M, Wisniewski S, Stewart J, Nierenberg A, Thase M, Ritz L, Biggs M, Warden D, Luther J, Shores-Wilson K, Niederehe G, Fava M. STAR*D Study Team. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1231–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trivedi M, Fava M, Wisniewski S, Thase M, Quitkin F, Warden D, Ritz L, Nierenberg A, Lebowitz B, Biggs M, Luther J, Shores-Wilson K, Rush A. STAR*D Study Team. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1243–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thase M, Friedman E, Biggs M, Wisniewski S, Trivedi M, Luther J, Fava M, Nierenberg A, McGrath P, Warden D, Niederehe G, Hollon S, Rush A. Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:739–52. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rush A, Wisniewski S, Warden D, Luther J, Davis L, Fava M, Nierenberg A, Trivedi M. Selecting among second-step antidepressant medication monotherapies: Are clinical, demographic, or first-step treatment results informative? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:870–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.8.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Posternak MA, Baer L, Nierenberg AA, Fava M. Response rates to fluoxetine in subjects who initially show no improvement. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(7):949–54. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cooper C, Katona C, Lyketsos K, Blazer D, Brodaty H, Rabins P, de Mendonça Lima CA, Livingston G. A systematic review of treatments for refractory depression in older people. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):681–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mulsant BH, Houck PR, Gildengers AG, Andreescu C, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Miller MD, Stack JA, Mazumdar S, Reynolds CF., 3rd What is the optimal duration of a short-term antidepressant trial when treating geriatric depression? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(2):113–20. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000204471.07214.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sackeim HA, Roose SP, Lavori PW. Determining the duration of antidepressant treatment: application of signal detection methodology and the need for duration adaptive designs (DAD). Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(6):483–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schiff GD, Galanter WL, Duhig J, Lodolce AE, Koronkowski MJ, Lambert BL. Principles of Conservative Prescribing. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(16):1433–1440. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reynolds FCF, III, Dew MA, Martire LM, Miller MD, Cyranowski JM, Lenze E, Whyte EM, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Karp JF, Gildengers A, Szanto K, Dombrovski AY, Andreescu C, Butters MA, Morse JQ, Houck PR, Bensasi S, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Frank E. Treating depression to remission in older adults: a controlled evaluation of combined escitalopram with interpersonal psychotherapy versus escitalopram with depression care management. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(11):1134–1141. doi: 10.1002/gps.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dombrovski, Mulsant 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blumberger DM, Mulsant BH, Fitzgerald PB, Rajji TK, Ravindran AV, Young LT, Levinson AJ, Daskalakis ZJ. A randomized double-blind sham controlled comparison of unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant major depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(6):423–435. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.579163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reynolds CF, III, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Frank E, Miller MD, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Butters MA, Stack JA, Schlernitzauer MA, Whyte EM, Gildengers A, Karp J, Lenze E, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kupfer DJ. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. New Eng J Med. 2006;354(11):1130–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: revised recommendations for Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) related to a potential risk of abnormal heart rhythms with high doses. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391.htm Accessed April 12, 2014.

- 70.Zivin K, Pfeiffer PN, Bohnert AS, Ganoczy D, Blow FC, Nallamothu BK, Kales HC. Evaluation of the FDA warning against prescribing citalopram at doses exceeding 40 mg. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):642–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12030408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, Devanand DP, Frangakis C, Ismail Z, Marano C, Meinert CL, Mintzer JE, Munro CA, Pelton G, Rabins PV, Rosenberg PB, Schneider LS, Shade DM, Weintraub D, Yesavage J, Lyketsos CG. CitAD Research Group. Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(7):682–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mulsant BH. Challenges of the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(4):317–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Physician Drug Reference Drug Summary - Cymbalta (duloxetine hydrochloride) 2014 http://www.pdr.net/drug-summary/cymbalta?druglabelid=288&id=2223 Accessed on April 14, 2014.

- 74.Schueler YB, Koesters M, Wieseler B, Grouven U, Kromp M, Kerekes MF, Kreis J, Kaiser T, Becker T, Weinmann S. A systematic review of duloxetine and venlafaxine in major depression, including unpublished data. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(4):247–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cipriani A, Koesters M, Furukawa TA, Nosè M, Purgato M, Omori IM, Trespidi C, Barbui C. Duloxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006533. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006533.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rocha FL, Fuzikawa C, Riera R, Hara C. Combination of antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):278–81. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318248581b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rajji TK, Mulsant BH, Lotrich FE, Lokker C, Reynolds CF., 3rd Use of antidepressants in late-life depression. Drugs & Aging. 2008;25(10):841–53. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chew, et al. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 79.American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012. 2012;60(4):616–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderson IM. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. J Affect Disord. 2000;58(1):19–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilson K, Mottram P. A comparison of side effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in older depressed patients: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(8):754–62. doi: 10.1002/gps.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Machado M, Iskedjian M, Ruiz I, Einarson TR. Remission, dropouts, and adverse drug reaction rates in major depressive disorder: ameta-analysis of head-to-head trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(9):1825–37. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.von Wolff A, Hölzel LP, Westphal A, Härter M, Kriston L. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in the acute treatment of chronic depression and dysthymia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2013;144(1-2):7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sheffrin M, Driscoll HC, Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Miller MD, Butters MA, Dew MA, Reynolds CF., 3rd Pilot study of augmentation with aripiprazole for incomplete response in late-life depression: getting to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(2):208–13. doi: 10.4088/jcp.07m03805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steffens DC, Nelson JC, Eudicone JM, Andersson C, Yang H, Tran QV, Forbes RA, Carlson BX, Berman RM. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder in older patients: a pooled subpopulation analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(6):564–72. doi: 10.1002/gps.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Katila H, Mezhebovsky I, Mulroy A, Berggren L, Eriksson H, Earley W, Datto C. Randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.010. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin RC, Chiu E, Katona C, et al. Guidelines on Depression in Older People: Practicing the Evidence. Martin Dunitz Ltd; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Harman JS, Mulsant BH, Kelleher KJ, Schulberg HC, Kupfer DJ, Reynolds CF., 3rd Narrowing the gap in treatment of depression. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(3):239–53. doi: 10.2190/Q3VY-T8V9-30MA-VC5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman MV. Clinical trials in psychiatry: do results apply to practice?’. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;46:352–355. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, Attiullah N, Friedman M, Boland RJ, Baymiller S, Berlowitz SL, Rahman S, Uy KK, Singer S, Chelminski I. Why isn't bupropion the most frequently prescribed antidepressant? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005a;66(5):603–10. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]