Abstract

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by elevated serum glucose levels and altered lipid metabolism, due to peripheral insulin resistance and defects of insulin secretion by the pancreatic β-cells. While some cases of obesity and Type 2 diabetes result from genetic dysfunction, the increased worldwide incidence of these two disorders strongly suggest that the contribution of environmental factors such as sedentary life-styles and high-calorie intake may disrupt energy balance. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and its upstream kinase LKB1 are conserved serine/threonine kinases regulating anabolic and catabolic metabolic processes, therefore representing attractive therapeutic targets for the treatment of obesity and Type 2 diabetes. In this review, we will discuss the advantages of targeting the LKB1/AMPK pathway for the treatment of metabolic diseases.

Keywords: AMPK, LKB1, Fyn kinase, insulin, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

The term metabolic syndrome describes a constellation of factors (obesity, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and glucose intolerance) that increase the risk for Type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease and stroke (1). While the causal link between these components of the metabolic syndrome is still under investigation, it is obvious that the events preceding the development of the syndrome itself are related to a dysfunction in whole body metabolic homeostasis.

Glucose, fatty acid and protein metabolism must be precisely maintained to insure energy homeostasis, and dysregulation of these processes results in states of weight loss or weight gain. At the whole organism level, maintenance of energy homeostasis depends on the ability of molecular and cellular mechanisms to efficiently couple energy intake with energy expenditure. For example, obesity is the result of a disordered balance between these two components and insulin resistance or impaired insulin action in skeletal muscle, fat, and liver is one of the earliest detectable defects associated with metabolic diseases. Following this initial phase of insulin resistance, pancreatic β-cells fail to secrete sufficient amounts of insulin to compensate for the increased energy supply, therefore leading to hyperglycemia. Lifestyle modifications such as dietary changes and regular exercise to loose weight are the first therapies for the management of Type 2 diabetes. However, when lifestyle intervention is not sufficient to improve and control serum glucose and lipid levels, drugs that increase insulin action and/or induce whole body energy consumption are appealing candidates to prevent and treat Type 2 diabetes. Anti-diabetic agents typically used to sustain adequate glycemic control lower the glucose by different mechanisms. For example, the α-glucosidase inhibitors block glucose absorption in the gut; the sulphonylureas stimulate β-cell insulin secretion; and the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor increases insulin secretion by increasing GLP-1 and GIP levels, which inhibit glucagon secretion (2; 3). Interestingly, two commonly used drugs that potentiate insulin action; metformin and the thiazolidinediones (TZD) family have been shown to activate the LKB1/AMPK pathway (4). Therefore, interest has focused upon the identification of drugs and basic cellular metabolic pathways that would activate AMPK to improve insulin sensitivity at cellular, tissue and organism levels.

AMPK an LKB1: two key enzymes in the nutrient-sensor pathway

1-AMPK and LKB1 structure and regulation

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a serine/threonine protein kinase that was originally identified as an upstream regulator of two main enzymes of lipid metabolism, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMGR). While the name AMP-activated protein kinase was first given in 1988, it was only in 1994 that mammalian AMPK was purified, sequenced and the catalytic subunit was found to be the homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae stress sensing kinase Snf1 (5; 6). Genetic studies have demonstrated that Snf1 is a protein critical for yeast survival and is responsible for turning on/off genes whose expression changes with glucose deprivation (7). Additionally, Woods et al. (5) showed that Snf1 was activated while yeast ACC activity was inhibited in conditions of low glucose availability, demonstrating that ACC was a downstream target for Snf1 (5). These observations provided evidence that AMPK/Snf1 kinases were key enzymes in the highly conserved metabolic stress-sensing pathway. Over the past 20 years, studies have demonstrated that mammalian AMPK plays an important role in the regulation of cellular and whole-body energy homeostasis. On this basis, AMPK is often considered a metabolic master-switch that mediates cellular adaptations to nutritional and environmental variations which deplete intracellular ATP levels, e.g hypoxia, starvation or prolonged exercise (8) (9; 10).

AMPK is a well-conserved heterotrimeric complex composed of three different subunits α, β, γ (11). In mammals, each AMPK complex combines a catalytic α subunit (α1 and α2), with β (β1 or β2) and γ (γ1, γ2, γ3) regulatory subunits encoded by separate genes, yielding 12 heterotrimeric combinations (8). In addition, the γ2 and γ3 subunits encoding genes give rise to short and long splice variants, adding to the diversity of the complex (9). Differences in expression level and tissue distribution and more recently subcellular distribution of the different subunits of AMPK have also been reported. For example, the α1 subunit was localized to non-nuclear fractions whereas the α2 and β subunits localize in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (12; 13) (14). In addition, the β1 subunit contains a myristoylation site in the N-terminal that can target it to the plasma membrane (15). The AMPK subunits also have different tissue distributions, with the catalytic subunit α1 expressed in the adipose tissue and the α2 subunit highly expressed in skeletal muscle along with the β2 and γ3 regulatory subunits (16–20). Although the precise functional role of the different AMPK subunits has not been entirely elucidated, heterotrimeric complexes containing the α1 subunit appear to be less AMP sensitive (21).

Regulation of AMPK appears to be a combination of direct allosteric activation by AMP and reversible phosphorylation of the T172 residue of the catalytic α subunit by upstream kinases, which is considered the main event responsible for the activation of AMPK since AMPK activity is increased by more than 1000-fold via phosphorylation (22; 23). In comparison, allosteric activation by AMP only increases AMPK activity by 5-fold (24). Under conditions of low cellular energy status, binding of AMP to the regulatory γ subunit of AMPK promotes allosteric activation that triggers an upstream kinase to phosphorylate T172 on the α subunit (25) (26). AMP also appears to prevent α subunit dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases, thereby maintaining AMPK in an activated state. In addition, AMPK can also be activated by modification of the NAD/NADH levels or Ca2+ independently of changes of adenine nucleotide levels (27; 28).

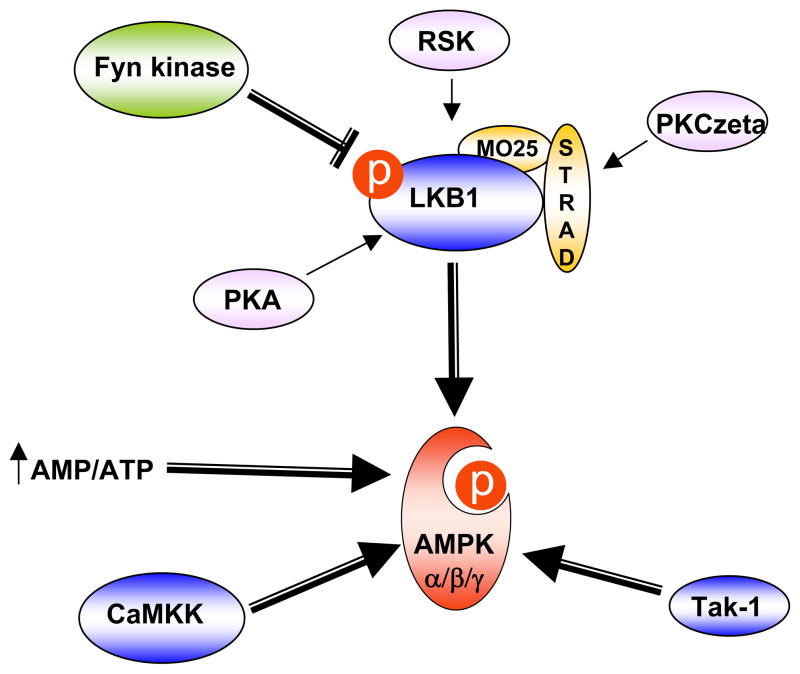

Based on several genetic studies performed in yeast, three upstream AMPK kinases have been identified (Fig. 1). (TGF)-β-activated kinase-1 (Tak-1) was recently identified as an upstream kinase for AMPK. However, whether Tak-1 directly or indirectly activates AMPK is still controversial (29; 30). In contrast, two other AMPK kinases have been shown to directly phosphorylate the AMPK α subunit on T172 (31–33). In neurons, calcium-stimulated activation of AMPK is dependent upon the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK) family that phosphorylates the α subunit T172 residue (31). Although CaMKKs have also been shown to activate AMPK in the skeletal muscle under mild tetanic contraction, CaMKK expression is very low in peripheral tissues and is primarily restricted to brain, testis, thymus and T-cells (34) (35). In contrast, LKB1 is expressed in insulin-responsive tissues and muscle-specific LKB1 knockout mice are unable to activate AMPKs (36–38). Although other factors can also regulate the activity of the AMPK since a residual phosphorylation is observed in the LKB1-deficient cells, LKB1 is considered the main enzyme that regulates AMPK activity under conditions of energy deprivation.

Figure 1. AMPK/LKB1 pathway regulation.

AMPK is regulated by direct allosteric activation (increase of the ratio AMP/ATP) and by reversible phosphorylation on the T172 residue of the catalytic α subunit. Several AMPK upstream kinases have been identified. CaMKK activates AMPK principally in the brain and LKB1 is considered the main AMPK upstream kinase in insulin responsive peripheral tissues. Recently, Tak-1 was also shown to activate AMPK. Regulation of LKB1 involves co-factor association (MO25 and STRAD) and phosphorylation by several upstream kinases such as PKA, RSK or PKCzeta. Recently, Fyn kinase was shown to regulate LKB1 activity through inhibitory phosphorylation of the Y216 and Y365 residues.

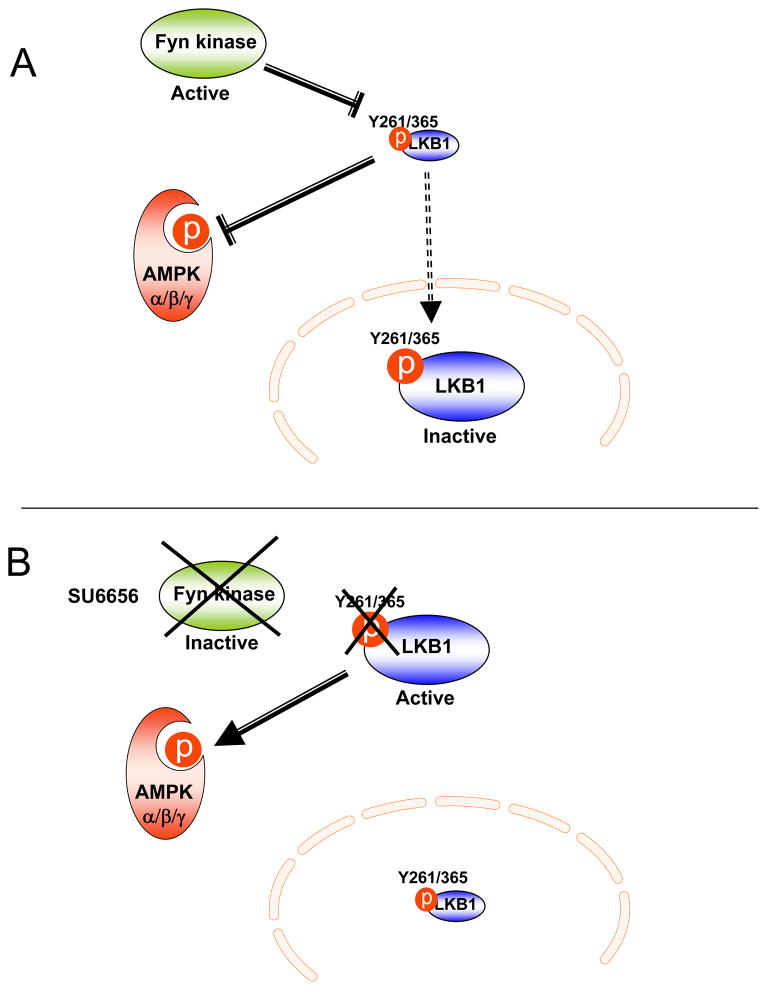

LKB1, a serine/threonine kinase originally identified as a tumor suppressor protein mutated in Peutz-Jegher syndrome, controls diverse cellular processes including cellular polarity, cancer and metabolism (39; 40). Regulation of LKB1 appears to be a complex process that involves phosphorylation on diverse residues (S31, S325, T366 and S431) and association into a ternary complex with one subunit of MO25 (MO25α or MO25β) and one subunit of STRAD (STRADα or STRADβ) (36; 41) (Fig. 1). Serine 431 in LKB1 is highly conserved in all organisms except Caenorhabditis elegans and is phosphorylated by p90 ribosomal S6 protein kinase (RSK) and protein kinase A (PKA) (42; 43). Although the phosphorylation of S431 was initially described as critical for LKB1 activity, recent studies have suggested that it might not be necessary and other activation mechanisms might occur (44). In particular, LKB1 subcellular localization is an important event regulating LKB1 activity since LKB1 functions as a tumor suppressor only when it localizes in the cytoplasm and appears to be inactive when restricted to the nucleus of cells (36). Several studies have aimed at determining the mechanisms of LKB1 nuclear export/import. It has been reported that LKB1 undergoes sirtuin-mediated deacetylation with the acetylated form restricted to the nucleus and the deacetylated form redistributed to the cytoplasm (45). In addition, S307 has been identified to trigger LKB1 nuclear export in response to PKCzeta stimulation and via increased association with STRADα and CRM1, a nuclear protein exportin (46). More recently, Fyn tyrosine kinase, a member of the Src family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases, was shown to directly phosphorylate LKB1 on tyrosine 261 and 365 residues and mutations of these sites in LKB1 sequence results in LKB1 export into the cytoplasm followed by increased AMPK phosphorylation (47) (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Fyn kinase-dependent regulation of the LKB1/AMPK pathway.

A) Fyn kinase phosphorylates LKB1 on Y261 and Y365 residues, inhibiting LKB1 activity and subsequently decreasing AMPK phosphorylation/activity. B) LKB1 is redistributed from the nucleus into the cytoplasm of cells treated with the Fyn kinase inhibitor, SU6656. The non-phosphorylated LKB1 form phosphorylates and activates AMPK.

2-Role of LKB1/AMPK in glucose metabolism

Physical activity improves lipid profile, decreases both body weight and percentage of fat mass and also affects muscle, adipose tissue and liver insulin sensitivity, leading to a general improvement of glycemia in obese and type 2 diabetic individuals. These beneficial effects are partly due to increased lipid oxidation and expression of proteins involved in mitochondria biogenesis, leading to an increase in the oxidative capacity of the skeletal muscle. Interestingly, AMPK activity is increased during physical activity and could mediate some of the favorable effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity, lipid and glucose utilization in the skeletal muscle and in extra-muscular tissues such as adipose tissue and liver (48). Interestingly, GLUT4-mediated glucose transport, hexokinase II and mitochondrial markers in skeletal muscle are increased by AICAR (5-Aminoimidazole-4-Carboxamide-1-β-D-Ribonucleoside), a pharmacological AMP mimetic that can serve as an AMPK agonist (49–51). In addition, discrepancy has been observed between α1 and α2 catalytic subunits since whole-body deletion of AMPKα1 does not result in any metabolic phenotype (52). On contrast, AMPKα2 knockout mice have increased adiposity (53; 54). However, these animals display only mild insulin-resistance. Similarly, glucose tolerance was not affected by the over-expression of a kinase-dead (KD) form of AMPKα2 in the cardiac muscle (49), although the contribution of the heart to whole body glucose disposal is relatively small. More recently, models of whole body knockout of β1 and β2 subunits of AMPK (55; 56) also showed phenotypic differences, possibly due to alterations of AMPKα subunits in different tissues or a central compensatory effect. The use of tissue specific deletions of β1 and β2 should help determine the role of these subunits in regulating muscle/liver metabolism and clarify the functions of each subunit of the αβγ heterotrimer.

Nonetheless, these studies suggest another pathway in conjunction with or independent of AMPK for the regulation of glucose/lipid homeostasis. In line with this, studies have demonstrated that exercise-induced glucose uptake is only partially affected in mice lacking AMPKα2 and in the muscle of the AMPKα2 dominant negative mice (52; 57). On the other hand, muscle-specific LKB1 knockout mice show a near complete inhibition of contraction-induced glucose uptake in the skeletal muscle with an ablated AMPKα activity (38). This discrepancy suggests additional mechanisms by which LKB1 controls exercise-mediated glucose transport. Interest has recently been focused on AMPK-related kinases, such as SNARK (58). A recent study has shown that SNARK activity is increased during muscle contraction and this effect was abolished in the muscle-specific LKB1 knockout mice (59). Whole-body SNARK heterozygotic knockout mice also have impaired contraction-stimulated glucose transport in the skeletal muscle (59). In addition, heterozygous deficient SNARK mice display increased adiposity and develop obesity with age (60), suggesting that SNARK could have a role in glucose and lipid metabolism.

In addition to the role of the LKB1/AMPK axis in skeletal muscle, AMPK was also shown to regulate glucose metabolism in liver. An important component of Type 2 diabetes is an increase in hepatic glucose production that is not repressed by insulin. Studies using the AMPK agonist, AICAR (61; 62), and transient expression of a constitutively active form of AMPKα2 in the liver of wild type animals (63), have revealed that the glucose lowering effects of AMPK activation were mediated by the regulation of the CREB regulated transcription co-activator 2 (TORC2) leading to the CREB-dependent transcription of PGC1-α and subsequently inhibition of PEPCK and glucose-6-phosphatase (64).

3-Role of LKB1/AMPK in fatty acid metabolism

In addition to its role in muscle and liver glucose utilization, AMPK also plays a critical role in the regulation of fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle and liver (65; 66). Increasing fatty acid utilization appears to be an attractive way to prevent both obesity and insulin resistance, which are also characterized by intra-muscular and hepatic lipid accumulation (67). In the liver, AMPK enhances fatty acid oxidation by phosphorylating the inhibitory site of the acetyl-CoA-carboxylase (ACC), one of the main rate-controlling enzymes for the synthesis of malonyl-CoA, which is the substrate for fatty acid synthesis and a potent allosteric inhibitor of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (68) (69; 70). Therefore, the inhibition of ACC via activation of AMPK leads to a drop of malonyl-CoA levels, de-repressing fatty acid oxidation and decreasing lipid accumulation. AMPK also represses pyruvate kinase and fatty acid synthase expression, thus contributing to decreased lipogenesis (20; 71; 72). The effects of AICAR in the skeletal muscle on fatty acid oxidation have been documented to be AMPK mediated (73). However, phosphorylation levels of ACC, a downstream target of AMPK, were increased in the skeletal muscle of mice expressing a kinase-dead form of AMPK. This suggests that other pathways independent of AMPK (i.e: modulation of malonyl-CoA levels by MCD) are involved in the regulation of fatty acid oxidation. However, AMPK activation is required for adiponectin and leptin-mediated fatty acid oxidation (74; 75). The latter acutely activates AMPK (76) and increases its expression (77) but leptin also has more prolonged effects on AMPK activation through the stimulation of α-adrenergic receptors in the muscle via mechanisms involving the sympathetic nervous system (78).

4-Role of LKB1/AMPK in pancreatic β-cells function

If left untreated, the asymptomatic insulin resistance phase of Type 2 Diabetes is followed by defects in insulin secretion that result in severe hyperglycemia. Chronic high glucose levels have been shown to deteriorate pancreatic β-cells metabolism, leading to elevated cytotoxic products, such as ceramides and diacylglycerol, that play a role in β-cell death, resulting in insulin secretion defects (79). The role of AMPK in the control of β-cell death and insulin secretion has generated numerous publications -sometimes with conflicting results. Several studies have demonstrated the pro-apoptotic role of AMPK in isolated β-cells ((80; 81) via enhanced mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (82; 83), leading to a decrease in β-cell mass. Therefore, activation of AMPK in β-cells appears to repress insulin secretion. In line with this, insulin secretion is increased in animal models that over-express a dominant negative form of AMPK (84) and AICAR inhibits glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (21), although a more recent study has shown that AICAR stimulates secretion in isolated islets (85). Differences between the cellular models and the molecular tools used in these studies might explain some of the discrepancies and this certainly highlights the complexity of the role of AMPK in β-cell function. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that stimulation of AMPK activity in prediabetic Zucker rats by systemic administration of AICAR prevented hyperglycemia, improved insulin sensitivity and preserved β-cell function (86). Therefore, the AMPK-mediated suppression of insulin secretion could have positive aspects since it would limit the toxic effects of glucose in pancreatic β-cells, and counteract the overproduction of insulin observed in the first stage of Type 2 diabetes. Counter-intuitively, by reducing insulin secretion and decreasing β-cell glycotoxicity, AMPK activation would protect pancreatic β-cell integrity and would ultimately reduce hyperglycemia and increase peripheral insulin responsiveness in Type 2 diabetic individuals.

5-Role of LKB1/AMPK in food intake regulation

The role of AMPK in the regulation of lipid, glucose metabolism and in general of energy homeostasis is not only restricted to AMPK action in peripheral tissues. AMPK is also widely expressed throughout the brain and in particular AMPK is found in neurons of the hypothalamus, suggesting a role for AMPK in the regulation of food intake (87). Interestingly, hypothalamic AMPK is regulated by energy availability as fasting increases and feeding decreases AMPK activity (88). Fasting and feeding are characterized by changes in nutrient availability such as glucose and hormone levels. Interestingly, low glucose concentrations or 2-deoxy-glucose treatment increase AMPK activity in ex-vivo hypothalamic cultures. On the other hand, high glucose or pyruvate supplementation decreases AMPK expression and phosphorylation levels (89; 90). In line with this, hypothalamic AMPK activity and food intake are increased in animals injected with 2-deoxy-glucose (91). In addition, acute peripheral or central hyperglycemia induction inhibits AMPK activity in several areas of the hypothalamus (88), in particular the arcuate nucleus (ARC), which contains neurons involved in the regulation of food intake, insulin sensitivity and energy expenditure. Hypothalamic AMPK activity is also altered under chronic dietary changes. However, suppression of the AMPK activity in the hypothalamus of diet-induced obese animals (92) might be attributable to other factors such as changes of insulin or leptin -and other adipokine- levels rather than solely changes of energy levels.

The role of AMPK in appetite regulation was first demonstrated by the injection of AICAR in either the third ventricle or the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (93). Minokoshi et al (93) soon after showed that expression of a dominant negative (DN) form of AMPK in the hypothalamus reduced food intake whereas the expression of a constitutively active (CA) form of AMPK had the opposite effect, demonstrating the importance of AMPK in the integration of energy states and nutrient signals, centrally. An important point to consider is that conventional AMPK (α2 or α1) knockout mice do not display alteration of food intake or energy expenditure, suggesting that other isoforms or compensatory pathways may substitute. Alternatively, this could result from a balanced inhibition of both orexigenic and anorexigenic neurons resulting in no net phenotype. Claret et al. (94) addressed this issue by specific analysis of AMPKα2 in orexigenic (NPY and AgRP) and anorexigenic (POMC) neurons of the hypothalamus. Deletion of AMPKα2 in AgRP (agouti-related protein) neurons resulted in a lean phenotype despite no alteration of food intake whereas deletion of AMPKα2 in the POMC (proopiomelanocortin) neurons surprisingly resulted in obese animals. In addition, AgRP-specific AMPK deletion resulted in impaired response to low glucose concentrations, illustrating the essential role of AMPK in glucose sensing.

The importance of hypothalamic AMPK activity in leptin-mediated appetite regulation was investigated in several studies. AICAR treatment or constitutively active AMPK expression in the hypothalamus were reported to inhibit the leptin anorexigenic effects (88; 95), suggesting that AMPK inhibition was necessary for leptin’s effects on food intake. However, in another study leptin-mediated inhibition of food intake was not altered in the AgRP-specific AMPK knockout animals (94). Hypothalamic AMPK activity is positively regulated by ghrelin (96), suggesting that AMPK could be part of orexigenic signaling. Interestingly, central regulation of AMPK by some hormones (i.e: leptin, ghrelin) is opposite to this of the periphery, possibly due to the tissue-specificity of upstream regulatory factors (kinase and phosphatase) of AMPK.

Targeted therapies

1-Insulin sensitizers

Since AMPK mediates glucose transport, fatty acid oxidation and mitochondria biogenesis in the skeletal muscle and inhibits hepatic glucose output, AMPK has emerged as a potential target for the treatment of obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Consequently, during the past decade, considerable efforts to determine molecules activating AMPK have been developed. Notably, AMPK activity is increased in response to two insulin sensitizers, metformin and the rosiglitazone (Fig. 2) (4). Rosiglitazone and in general the thiazolidinedione family (TZD) have been shown to activate AMPK in skeletal muscle via the increase of the AMP/ATP ratio and/or the enhancement of adiponectin secretion (4; 97). In addition, TZD treatment delays Type 2 diabetes in individuals already affected with impaired fasting glucose (98). Since the early 1950s, the biguanine drug metformin was used to treat Type 2 diabetes and other cardiovascular complications associated with obesity. Although metformin increases AMPK in the skeletal muscle and enhanced peripheral glucose uptake in diabetic patients (99; 100), the main glucose-lowering effects of metformin have been attributed to its ability to suppress hepatic glucose production via a mechanism mediated by LKB1. The LKB1/AMPK pathway was reported to regulate the phosphorylation of the CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 2 (TORC2), increasing CREB activity and subsequently activating PCG1α transcription and inhibiting gluconeogenesis (101). However, evidence has also pointed to a direct phosphorylation of the CREB-binding protein rather than TORC2 to mediate the effects of metformin on PEPCK and glucose-6-phosphatase inhibition (102). In addition, a recent study suggests that the inhibitory effects of metformin on gluconeogenesis are linked to a reduction of the cellular energy charge, that is a decrease of ATP, rather than the LKB1/AMPK pathway itself (103). Moreover, in this same study the authors also demonstrate that metformin lowers blood glucose levels in liver of AMPK-deficient mice, suggesting an AMPK-independent pathway to control hepatic glucose production and demonstrating the complexity of the mechanism of metformin action.

Figure 2. Diverse AMPK activators.

AMPK activity is increased by diverse factors such as low glucose conditions, exercise, adipokines (i.e leptin and adiponectin), AICAR and insulin sensitizing agents such as metformin or thiazolidinediones (TZD).

2- Fyn kinase as a novel target to control the LKB1/AMPK action

While the mechanisms underlying the effects of insulin sensitizing agents are still under investigation, the LKB1/AMPK axis remains one of most promising targets to treat the deleterious effects of Type 2 diabetes. The identification of upstream factors regulating LKB1 and AMPK are an attractive path of research. Recently, we have reported that the Src kinase family member Fyn played a role in insulin sensitivity and lipid utilization in vivo (104).

2-a-Fyn kinase in the insulin signaling

Fyn kinase is one of the nine members of the Src family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases. The biological functions of Fyn kinase are diverse and include regulation of mitogenic signaling and cell cycle entry, proliferation, integrin-mediated interactions, reproduction and fertilization, axonal guidance, and differentiation of oligodendrocytes and keratinocytes (105–107). Fyn kinase has largely been described for its role in immune function (108–111) (112). However, beside these complex developmental phenotypes, several studies have implicated Fyn kinase -and the Src kinase family- in the regulation of insulin signaling through the lipid raft microdomains of the plasma membrane. Indeed, post-translational modifications redistribute Fyn kinase reversibly from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane, in particular to the lipid rafts (113). Fyn kinase phosphorylates caveolin in response to insulin stimulation in the 3T3L1 adipocytes (114) and also interacts with other proteins such as flotilin (115) and CD36 (116) that are components of the lipids rafts. In this regard, the physical association of Fyn kinase with CD36, also know as FAT (fatty acid translocase), suggested a connection between the insulin signaling via the lipid raft organization and the regulation of fatty acid uptake and/or oxidation. In addition, Fyn kinase has also been shown to activate the PI3-kinase signaling pathway through the direct interactions with c-Cbl (117) and IRS1 (118). More recently, a study showed that a constitutively active form of Src inhibits pyruvate kinase (119). Finally, a study has shown that pharmacological inhibition of the Src kinase family inhibited 3T3L1 adipocyte differentiation (120). Together these studies suggested a role for Fyn kinase in the insulin signaling.

2-b-Fyn kinase as a new molecule in the nutrient-sensing pathway

Recently, we have reported that conventional Fyn knockout mice displayed a marked reduction in adiposity, reduced fasting glucose and insulin levels and markedly improved insulin sensitivity (104). Fyn kinase deficiency also results in improved plasma and tissue triglycerides levels as well as elevation of the energy expenditure and enhanced fatty acid oxidation. Importantly, the enhanced catabolism predominantly occurred during the fasted states and the Fyn-deficient mice were able to convert to an adequate anabolic state during the feeding cycle. Interestingly, mitochondrial markers and AMPK phosphorylation and activity were increased in the adipose tissue and the skeletal muscle of the Fyn knockout mice. More recently, the pharmacological inhibition of the Src family was shown to prevent 3T3L1 lipid accumulation (120). Similarly, the acute systemic pharmacological inhibition of Fyn kinase by the inhibitor SU6656 in wild type mice induced weight loss via decreased adipose tissue mass without affecting the lean mass. These effects were due to increased fatty acid oxidation associated with whole-body energy expenditure, therefore reproducing the metabolic effects observed in the Fyn knockout mice (47). More importantly, a direct interaction between Fyn kinase and LKB1 was recently demonstrated, as Fyn kinase phosphorylates LKB1 on two tyrosine residues (Y261 and Y365) and modulates LKB1 subcellular localization. Mutations of Y261 and Y365 resulted in LKB1 being re-localized into the cytoplasm of muscle cells and subsequent increase in AMPK phosphorylation, demonstrating a cross talk between the AMPK pathway and Fyn kinase, via Fyn-dependent regulation of LKB1 (Fig. 3).

These findings suggest that developing a pharmacological intervention to inhibit Fyn function would have the potential to induce selective weight loss by decreasing fat mass and simultaneously increasing insulin sensitivity. However, while there is only one fyn gene, three splice variants have been described, encoding for three Fyn isoforms with distinct structural properties, levels of enzymatic activity, tissue distribution and signaling pathways (111; 121–123). This suggests that Fyn-dependent LKB1/AMPK regulation might differ accordingly to the Fyn kinase isoform expressed in a particular tissue. Therefore, additional work is necessary to precisely determine the role of the different isoforms- and their potential inhibition- in the regulation of LKB1 phosphorylation and subcellular localization. Nonetheless, these data establish Fyn kinase as a novel nutrient-sensor coupled to AMPK and suggest that altering the Fyn-dependent regulation of LKB1 either by directly inhibiting Fyn kinase activity of disturbing the interaction between Fyn and LKB1 may have potential benefits for the treatment of obesity and Type 2 Diabetes.

Executive summary.

Obesity and Type 2 diabetes are the result of an inadequate balance between energy intake and energy expenditure.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and its upstream kinase LKB1 regulate glucose and lipid metabolism in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and liver.

Metformin is one of the the main therapeutic agents for the treatment of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes and primarily functions by reducing hepatic glucose production. Metformin lowers ATP levels, resulting in the activation of the AMPK/LKB1 nutrient sensor pathway. However, recent studies have suggested that the glucose lowering effects of metformin also occur via an AMPK-independent pathway.

The identification of upstream factors regulating LKB1 and AMPK are an attractive path of research for the treatment of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

Fyn kinase, a member of the Src kinase family, was recently shown to phosphorylate LKB1 and subsequently regulate LKB1 subcellular localization, which allowed LKB1 to either interact or not interact with AMPK. Therefore Fyn kinase represents a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

Future perspectives.

Currently, approximately 300 million individuals worldwide are obese with 40 million obese individuals in the US alone. Obesity is the largest risk factor for the development of Type 2 diabetes, which is preceded by impaired insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in peripheral tissues and impaired inhibition of hepatic glucose output. Type 2 Diabetes and insulin resistance are also associated with a cluster of diseases described as the metabolic syndrome. Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches are urgently needed to prevent and treat these disorders. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) represents an attractive target in the prevention of Type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance since several AMPK activators have been successfully used to reduce basal glucose levels in diabetic animals. However due to the widespread expression and functions of AMPK, concerns about the possible deleterious consequences of the use of AMPK activators in humans have been raised. The recent identification of upstream regulators of AMPK opens a new pathway for the development of specific therapeutic interventions directed specifically at key tissues.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by grants from the Ellison Medical Foundation (New Scholar Award in Aging) and the National Institutes of Health (DK078886).

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- Snf1

Sucrose-Non-fermenting factor 1

- AICAR

5-Aminoimidazole-4-Carboxamide-1-β-D-Ribonucleoside

- ACC

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- CaMKK

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase

- Tak-1

(TGF)-β-activated kinase-1

- TORC2

CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 2

- TZD

thiazolidinedione

- PKA

protein kinase A

- RSK

p90 ribosomal S6 protein kinase

- PKCzeta

protein kinase C zeta

References

- 1.Aschner P. Metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for diabetes. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 8:407–412. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirby M, Yu DM, O’Connor S, Gorrell MD. Inhibitor selectivity in the clinical application of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition. Clin Sci (Lond) 118:31–41. doi: 10.1042/CS20090047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Alessio DA, Denney AM, Hermiller LM, Prigeon RL, Martin JM, Tharp WG, Saylan ML, He Y, Dunning BE, Foley JE, Pratley RE. Treatment with the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor vildagliptin improves fasting islet-cell function in subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:81–88. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fryer LG, Parbu-Patel A, Carling D. The Anti-diabetic drugs rosiglitazone and metformin stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase through distinct signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25226–25232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woods A, Munday MR, Scott J, Yang X, Carlson M, Carling D. Yeast SNF1 is functionally related to mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase and regulates acetyl-CoA carboxylase in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19509–19515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stapleton D, Gao G, Michell BJ, Widmer J, Mitchelhill K, Teh T, House CM, Witters LA, Kemp BE. Mammalian 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase non-catalytic subunits are homologs of proteins that interact with yeast Snf1 protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29343–29346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polge C, Thomas M. SNF1/AMPK/SnRK1 kinases, global regulators at the heart of energy control? Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardie DG. AMPK: a key regulator of energy balance in the single cell and the whole organism. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32 (Suppl 4):S7–12. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viollet B, Athea Y, Mounier R, Guigas B, Zarrinpashneh E, Horman S, Lantier L, Hebrard S, Devin-Leclerc J, Beauloye C, Foretz M, Andreelli F, Ventura-Clapier R, Bertrand L. AMPK: Lessons from transgenic and knockout animals. Front Biosci. 2009;14:19–44. doi: 10.2741/3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Steinberg GR, Kemp BE. AMPK in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1025–1078. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2008. Review on AMPK structure, functions and activation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woods A, Cheung PC, Smith FC, Davison MD, Scott J, Beri RK, Carling D. Characterization of AMP-activated protein kinase beta and gamma subunits. Assembly of the heterotrimeric complex in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10282–10290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salt I, Celler JW, Hawley SA, Prescott A, Woods A, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: greater AMP dependence, and preferential nuclear localization, of complexes containing the alpha2 isoform. Biochem J. 1998;334 (Pt 1):177–187. doi: 10.1042/bj3340177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kodiha M, Rassi JG, Brown CM, Stochaj U. Localization of AMP kinase is regulated by stress, cell density, and signaling through the MEK-->ERK1/2 pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1427–1436. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00176.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki A, Okamoto S, Lee S, Saito K, Shiuchi T, Minokoshi Y. Leptin stimulates fatty acid oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene expression in mouse C2C12 myoblasts by changing the subcellular localization of the alpha2 form of AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4317–4327. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02222-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warden SM, Richardson C, O’Donnell J, Jr, Stapleton D, Kemp BE, Witters LA. Post-translational modifications of the beta-1 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase affect enzyme activity and cellular localization. Biochem J. 2001;354:275–283. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stapleton D, Mitchelhill KI, Gao G, Widmer J, Michell BJ, Teh T, House CM, Fernandez CS, Cox T, Witters LA, Kemp BE. Mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase subfamily. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:611–614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhoeven AJ, Woods A, Brennan CH, Hawley SA, Hardie DG, Scott J, Beri RK, Carling D. The AMP-activated protein kinase gene is highly expressed in rat skeletal muscle. Alternative splicing and tissue distribution of the mRNA. Eur J Biochem. 1995;228:236–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thornton C, Snowden MA, Carling D. Identification of a novel AMP-activated protein kinase beta subunit isoform that is highly expressed in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12443–12450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z, Heierhorst J, Mann RJ, Mitchelhill KI, Michell BJ, Witters LA, Lynch GS, Kemp BE, Stapleton D. Expression of the AMP-activated protein kinase beta1 and beta2 subunits in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1999;460:343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods A, Azzout-Marniche D, Foretz M, Stein SC, Lemarchand P, Ferre P, Foufelle F, Carling D. Characterization of the role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the regulation of glucose-activated gene expression using constitutively active and dominant negative forms of the kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6704–6711. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6704-6711.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salt IP, Johnson G, Ashcroft SJ, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase is activated by low glucose in cell lines derived from pancreatic beta cells, and may regulate insulin release. Biochem J. 1998;335 (Pt 3):533–539. doi: 10.1042/bj3350533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardie DG. The AMP-activated protein kinase pathway--new players upstream and downstream. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5479–5487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardie DG, Hawley SA, Scott JW. AMP-activated protein kinase--development of the energy sensor concept. J Physiol. 2006;574:7–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suter M, Riek U, Tuerk R, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Neumann D. Dissecting the role of 5′-AMP for allosteric stimulation, activation, and deactivation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32207–32216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein SC, Woods A, Jones NA, Davison MD, Carling D. The regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by phosphorylation. Biochem J. 2000;345(Pt 3):437–443. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musi N. AMP-activated protein kinase and type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:583–589. doi: 10.2174/092986706776055724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rafaeloff-Phail R, Ding L, Conner L, Yeh WK, McClure D, Guo H, Emerson K, Brooks H. Biochemical regulation of mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase activity by NAD and NADH. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52934–52939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurley RL, Anderson KA, Franzone JM, Kemp BE, Means AR, Witters LA. The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases are AMP-activated protein kinase kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29060–29066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Momcilovic M, Hong SP, Carlson M. Mammalian TAK1 activates Snf1 protein kinase in yeast and phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25336–25343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie M, Zhang D, Dyck JR, Li Y, Zhang H, Morishima M, Mann DL, Taffet GE, Baldini A, Khoury DS, Schneider MD. A pivotal role for endogenous TGF-beta-activated kinase-1 in the LKB1/AMP-activated protein kinase energy-sensor pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17378–17383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604708103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawley SA, Pan DA, Mustard KJ, Ross L, Bain J, Edelman AM, Frenguelli BG, Hardie DG. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab. 2005;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawley SA, Boudeau J, Reid JL, Mustard KJ, Udd L, Makela TP, Alessi DR, Hardie DG. Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRAD alpha/beta and MO25 alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol. 2003;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, Hurley RL, Witters LA, DePinho RA, Cantley LC. The tumor suppressor LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates apoptosis in response to energy stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3329–3335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308061100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen TE, Rose AJ, Jorgensen SB, Brandt N, Schjerling P, Wojtaszewski JF, Richter EA. Possible CaMKK-dependent regulation of AMPK phosphorylation and glucose uptake at the onset of mild tetanic skeletal muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1308–1317. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00456.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson KA, Means RL, Huang QH, Kemp BE, Goldstein EG, Selbert MA, Edelman AM, Fremeau RT, Means AR. Components of a calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade. Molecular cloning, functional characterization and cellular localization of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase beta. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31880–31889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36**.Alessi DR, Sakamoto K, Bayascas JR. LKB1-dependent signaling pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:137–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142702. A complete review on LKB1 structure and functions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakamoto K, Goransson O, Hardie DG, Alessi DR. Activity of LKB1 and AMPK-related kinases in skeletal muscle: effects of contraction, phenformin, and AICAR. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E310–317. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00074.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakamoto K, McCarthy A, Smith D, Green KA, Grahame Hardie D, Ashworth A, Alessi DR. Deficiency of LKB1 in skeletal muscle prevents AMPK activation and glucose uptake during contraction. EMBO J. 2005;24:1810–1820. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hemminki A, Tomlinson I, Markie D, Jarvinen H, Sistonen P, Bjorkqvist AM, Knuutila S, Salovaara R, Bodmer W, Shibata D, de la Chapelle A, Aaltonen LA. Localization of a susceptibility locus for Peutz-Jeghers syndrome to 19p using comparative genomic hybridization and targeted linkage analysis. Nat Genet. 1997;15:87–90. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jenne DE, Reimann H, Nezu J, Friedel W, Loff S, Jeschke R, Muller O, Back W, Zimmer M. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Genet. 1998;18:38–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baas AF, Boudeau J, Sapkota GP, Smit L, Medema R, Morrice NA, Alessi DR, Clevers HC. Activation of the tumour suppressor kinase LKB1 by the STE20-like pseudokinase STRAD. EMBO J. 2003;22:3062–3072. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sapkota GP, Kieloch A, Lizcano JM, Lain S, Arthur JS, Williams MR, Morrice N, Deak M, Alessi DR. Phosphorylation of the protein kinase mutated in Peutz-Jeghers cancer syndrome, LKB1/STK11, at Ser431 by p90(RSK) and cAMP-dependent protein kinase, but not its farnesylation at Cys(433), is essential for LKB1 to suppress cell vrowth. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19469–19482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009953200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins SP, Reoma JL, Gamm DM, Uhler MD. LKB1, a novel serine/threonine protein kinase and potential tumour suppressor, is phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and prenylated in vivo. Biochem J. 2000;345(Pt 3):673–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fogarty S, Hardie DG. C-terminal phosphorylation of LKB1 is not required for regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase, BRSK1, BRSK2, or cell cycle arrest. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:77–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806152200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lan F, Cacicedo JM, Ruderman N, Ido Y. SIRT1 modulation of the acetylation status, cytosolic localization, and activity of LKB1. Possible role in AMP-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27628–27635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805711200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie Z, Dong Y, Zhang J, Scholz R, Neumann D, Zou MH. Identification of the serine 307 of LKB1 as a novel phosphorylation site essential for its nucleocytoplasmic transport and endothelial cell angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3582–3596. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01417-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47**.Yamada E, Pessin JE, Kurland IJ, Schwartz GJ, Bastie CC. Fyn-dependent regulation of energy expenditure and body weight is mediated by tyrosinephosphorylation of LKB1. Cell Metab. 11:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.12.010. Study demonstrating that Fyn kinase phosphorylates LKB1 and regulates LKB1 subcellular localization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruderman NB, Park H, Kaushik VK, Dean D, Constant S, Prentki M, Saha AK. AMPK as a metabolic switch in rat muscle, liver and adipose tissue after exercise. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;178:435–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mu J, Brozinick JT, Jr, Valladares O, Bucan M, Birnbaum MJ. A role for AMP-activated protein kinase in contraction- and hypoxia-regulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurth-Kraczek EJ, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Winder WW. 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase activation causes GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 1999;48:1667–1671. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bergeron R, Russell RR, 3rd, Young LH, Ren JM, Marcucci M, Lee A, Shulman GI. Effect of AMPK activation on muscle glucose metabolism in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E938–944. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.5.E938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jorgensen SB, Viollet B, Andreelli F, Frosig C, Birk JB, Schjerling P, Vaulont S, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF. Knockout of the alpha2 but not alpha1 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase isoform abolishes 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranosidebut not contraction-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1070–1079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villena JA, Viollet B, Andreelli F, Kahn A, Vaulont S, Sul HS. Induced adiposity and adipocyte hypertrophy in mice lacking the AMP-activated protein kinase-alpha2 subunit. Diabetes. 2004;53:2242–2249. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viollet B, Andreelli F, Jorgensen SB, Perrin C, Geloen A, Flamez D, Mu J, Lenzner C, Baud O, Bennoun M, Gomas E, Nicolas G, Wojtaszewski JF, Kahn A, Carling D, Schuit FC, Birnbaum MJ, Richter EA, Burcelin R, Vaulont S. The AMP-activated protein kinase alpha2 catalytic subunit controls whole-body insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:91–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI16567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dzamko N, van Denderen BJ, Hevener AL, Jorgensen SB, Honeyman J, Galic S, Chen ZP, Watt MJ, Campbell DJ, Steinberg GR, Kemp BE. AMPK beta1 deletion reduces appetite, preventing obesity and hepatic insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 285:115–122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steinberg GR, O’Neill HM, Dzamko NL, Galic S, Naim T, Koopman R, Jorgensen SB, Honeyman J, Hewitt K, Chen ZP, Schertzer JD, Scott J, Koentgen F, Lynch GS, Watt MJ, Vandenderen BJ, Campbell DJ, Kemp BE. Whole-body deletion of AMPK {beta}2 reduces muscle AMPK and exercise capacity. J Biol Chem. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujii N, Hirshman MF, Kane EM, Ho RC, Peter LE, Seifert MM, Goodyear LJ. AMP-activated protein kinase alpha2 activity is not essential for contraction- and hyperosmolarity-induced glucose transport in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39033–39041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Egan B, Zierath JR. Hunting for the SNARK in metabolic disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E969–972. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00178.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koh HJ, Toyoda T, Fujii N, Jung MM, Rathod A, Middelbeek RJ, Lessard SJ, Treebak JT, Tsuchihara K, Esumi H, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Sucrose nonfermenting AMPK-related kinase (SNARK) mediates contraction-stimulated glucose transport in mouse skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:15541–15546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008131107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsuchihara K, Ogura T, Fujioka R, Fujii S, Kuga W, Saito M, Ochiya T, Ochiai A, Esumi H. Susceptibility of Snark-deficient mice to azoxymethane-induced colorectal tumorigenesis and the formation of aberrant crypt foci. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:677–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lochhead PA, Salt IP, Walker KS, Hardie DG, Sutherland C. 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside mimics the effects of insulin on the expression of the 2 key gluconeogenic genes PEPCK and glucose-6-phosphatase. Diabetes. 2000;49:896–903. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Viana AY, Sakoda H, Anai M, Fujishiro M, Ono H, Kushiyama A, Fukushima Y, Sato Y, Oshida Y, Uchijima Y, Kurihara H, Asano T. Role of hepatic AMPK activation in glucose metabolism and dexamethasone-induced regulation of AMPK expression. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;73:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foretz M, Ancellin N, Andreelli F, Saintillan Y, Grondin P, Kahn A, Thorens B, Vaulont S, Viollet B. Short-term overexpression of a constitutively active form of AMP-activated protein kinase in the liver leads to mild hypoglycemia and fatty liver. Diabetes. 2005;54:1331–1339. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koo SH, Flechner L, Qi L, Zhang X, Screaton RA, Jeffries S, Hedrick S, Xu W, Boussouar F, Brindle P, Takemori H, Montminy M. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature. 2005;437:1109–1111. doi: 10.1038/nature03967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merrill GF, Kurth EJ, Hardie DG, Winder WW. AICA riboside increases AMP-activated protein kinase, fatty acid oxidation, and glucose uptake in rat muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E1107–1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.6.E1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Assifi MM, Suchankova G, Constant S, Prentki M, Saha AK, Ruderman NB. AMP-activated protein kinase and coordination of hepatic fatty acid metabolism of starved/carbohydrate-refed rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E794–800. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00144.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Lipid-induced insulin resistance: unravelling the mechanism. Lancet. 375:2267–2277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60408-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saddik M, Gamble J, Witters LA, Lopaschuk GD. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase regulation of fatty acid oxidation in the heart. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25836–25845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McGarry JD, Brown NF. The mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase system. From concept to molecular analysis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cook GA, Gamble MS. Regulation of carnitine palmitoyltransferase by insulin results in decreased activity and decreased apparent Ki values for malonyl-CoA. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2050–2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leclerc I, Kahn A, Doiron B. The 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits the transcriptional stimulation by glucose in liver cells, acting through the glucose response complex. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Foretz M, Carling D, Guichard C, Ferre P, Foufelle F. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits the glucose-activated expression of fatty acid synthase gene in rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14767–14771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee WJ, Kim M, Park HS, Kim HS, Jeon MJ, Oh KS, Koh EH, Won JC, Kim MS, Oh GT, Yoon M, Lee KU, Park JY. AMPK activation increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle by activating PPARalpha and PGC-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, Mori Y, Ide T, Murakami K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Ezaki O, Akanuma Y, Gavrilova O, Vinson C, Reitman ML, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Yoda M, Nakano Y, Tobe K, Nagai R, Kimura S, Tomita M, Froguel P, Kadowaki T. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Peroni OD, Fryer LG, Muller C, Carling D, Kahn BB. Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2002;415:339–343. doi: 10.1038/415339a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kamohara S, Burcelin R, Halaas JL, Friedman JM, Charron MJ. Acute stimulation of glucose metabolism in mice by leptin treatment. Nature. 1997;389:374–377. doi: 10.1038/38717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Steinberg GR, Rush JW, Dyck DJ. AMPK expression and phosphorylation are increased in rodent muscle after chronic leptin treatment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E648–654. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00318.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Minokoshi Y, Haque MS, Shimazu T. Microinjection of leptin into the ventromedial hypothalamus increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues in rats. Diabetes. 1999;48:287–291. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El-Assaad W, Buteau J, Peyot ML, Nolan C, Roduit R, Hardy S, Joly E, Dbaibo G, Rosenberg L, Prentki M. Saturated fatty acids synergize with elevated glucose to cause pancreatic beta-cell death. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4154–4163. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kefas BA, Cai Y, Ling Z, Heimberg H, Hue L, Pipeleers D, Van de Casteele M. AMP-activated protein kinase can induce apoptosis of insulin-producing MIN6 cells through stimulation of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;30:151–161. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0300151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kefas BA, Heimberg H, Vaulont S, Meisse D, Hue L, Pipeleers D, Van de Casteele M. AICA-riboside induces apoptosis of pancreatic beta cells through stimulation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetologia. 2003;46:250–254. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-1030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cai Y, Martens GA, Hinke SA, Heimberg H, Pipeleers D, Van de Casteele M. Increased oxygen radical formation and mitochondrial dysfunction mediate beta cell apoptosis under conditions of AMP-activated protein kinase stimulation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Riboulet-Chavey A, Diraison F, Siew LK, Wong FS, Rutter GA. Inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase protects pancreatic beta-cells from cytokine-mediated apoptosis and CD8+ T-cell-induced cytotoxicity. Diabetes. 2008;57:415–423. doi: 10.2337/db07-0993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.da Silva Xavier G, Leclerc I, Varadi A, Tsuboi T, Moule SK, Rutter GA. Role for AMP-activated protein kinase in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and preproinsulin gene expression. Biochem J. 2003;371:761–774. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gleason CE, Lu D, Witters LA, Newgard CB, Birnbaum MJ. The role of AMPK and mTOR in nutrient sensing in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10341–10351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pold R, Jensen LS, Jessen N, Buhl ES, Schmitz O, Flyvbjerg A, Fujii N, Goodyear LJ, Gotfredsen CF, Brand CL, Lund S. Long-term AICAR administration and exercise prevents diabetes in ZDF rats. Diabetes. 2005;54:928–934. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Turnley AM, Stapleton D, Mann RJ, Witters LA, Kemp BE, Bartlett PF. Cellular distribution and developmental expression of AMP-activated protein kinase isoforms in mouse central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1707–1716. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Minokoshi Y, Alquier T, Furukawa N, Kim YB, Lee A, Xue B, Mu J, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Birnbaum MJ, Stuck BJ, Kahn BB. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2004;428:569–574. doi: 10.1038/nature02440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee K, Li B, Xi X, Suh Y, Martin RJ. Role of neuronal energy status in the regulation of adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase, orexigenic neuropeptides expression, and feeding behavior. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3–10. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chau-Van C, Gamba M, Salvi R, Gaillard RC, Pralong FP. Metformin inhibits adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated kinase activation and prevents increases in neuropeptide Y expression in cultured hypothalamic neurons. Endocrinology. 2007;148:507–511. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim MS, Park JY, Namkoong C, Jang PG, Ryu JW, Song HS, Yun JY, Namgoong IS, Ha J, Park IS, Lee IK, Viollet B, Youn JH, Lee HK, Lee KU. Anti-obesity effects of alpha-lipoic acid mediated by suppression of hypothalamic AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med. 2004;10:727–733. doi: 10.1038/nm1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martin TL, Alquier T, Asakura K, Furukawa N, Preitner F, Kahn BB. Diet-induced obesity alters AMP kinase activity in hypothalamus and skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18933–18941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Andersson U, Filipsson K, Abbott CR, Woods A, Smith K, Bloom SR, Carling D, Small CJ. AMP-activated protein kinase plays a role in the control of food intake. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12005–12008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Claret M, Smith MA, Batterham RL, Selman C, Choudhury AI, Fryer LG, Clements M, Al-Qassab H, Heffron H, Xu AW, Speakman JR, Barsh GS, Viollet B, Vaulont S, Ashford ML, Carling D, Withers DJ. AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2325–2336. doi: 10.1172/JCI31516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mountjoy PD, Bailey SJ, Rutter GA. Inhibition by glucose or leptin of hypothalamic neurons expressing neuropeptide Y requires changes in AMP-activated protein kinase activity. Diabetologia. 2007;50:168–177. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kola B, Hubina E, Tucci SA, Kirkham TC, Garcia EA, Mitchell SE, Williams LM, Hawley SA, Hardie DG, Grossman AB, Korbonits M. Cannabinoids and ghrelin have both central and peripheral metabolic and cardiac effects via AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25196–25201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tomas E, Tsao TS, Saha AK, Murrey HE, Zhang CcC, Itani SI, Lodish HF, Ruderman NB. Enhanced muscle fat oxidation and glucose transport by ACRP30 globular domain: acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibition and AMP-activated protein kinase activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16309–16313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222657499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gerstein HC, Yusuf S, Bosch J, Pogue J, Sheridan P, Dinccag N, Hanefeld M, Hoogwerf B, Laakso M, Mohan V, Shaw J, Zinman B, Holman RR. Effect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1096–1105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Musi N, Hirshman MF, Nygren J, Svanfeldt M, Bavenholm P, Rooyackers O, Zhou G, Williamson JM, Ljunqvist O, Efendic S, Moller DE, Thorell A, Goodyear LJ. Metformin increases AMP-activated protein kinase activity in skeletal muscle of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2074–2081. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Goodarzi MO, Bryer-Ash M. Metformin revisited: re-evaluation of its properties and role in the pharmacopoeia of modern antidiabetic agents. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2005;7:654–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shaw RJ, Lamia KA, Vasquez D, Koo SH, Bardeesy N, Depinho RA, Montminy M, Cantley LC. The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science. 2005;310:1642–1646. doi: 10.1126/science.1120781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.He L, Sabet A, Djedjos S, Miller R, Sun X, Hussain MA, Radovick S, Wondisford FE. Metformin and insulin suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis through phosphorylation of CREB binding protein. Cell. 2009;137:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103**.Foretz M, Hebrard S, Leclerc J, Zarrinpashneh E, Soty M, Mithieux G, Sakamoto K, Andreelli F, Viollet B. Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice independently of the LKB1/AMPK pathway via a decrease in hepatic energy state. J Clin Invest. 120:2355–2369. doi: 10.1172/JCI40671. Study demonstrating the glucose lowering effects of metformin are not mediated by AMPK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104*.Bastie CC, Zong H, Xu J, Busa B, Judex S, Kurland IJ, Pessin JE. Integrative metabolic regulation of peripheral tissue fatty acid oxidation by the SRC kinase family member Fyn. Cell Metab. 2007;5:371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.04.005. Study demonstrating the Fyn kinase play an important role in lipid metabolism. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Saito YD, Jensen AR, Salgia R, Posadas EM. Fyn: a novel molecular target in cancer. Cancer. 116:1629–1637. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sperber BR, Boyle-Walsh EA, Engleka MJ, Gadue P, Peterson AC, Stein PL, Scherer SS, McMorris FA. A unique role for Fyn in CNS myelination. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2039–2047. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02039.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Engen JR, Wales TE, Hochrein JM, Meyn MA, 3rd, Banu Ozkan S, Bahar I, Smithgall TE. Structure and dynamic regulation of Src-family kinases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3058–3073. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8122-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Picard C, Gilles A, Pontarotti P, Olive D, Collette Y. Cutting edge: recruitment of the ancestral fyn gene during emergence of the adaptive immune system. J Immunol. 2002;168:2595–2598. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Salmond RJ, Filby A, Qureshi I, Caserta S, Zamoyska R. T-cell receptor proximal signaling via the Src-family kinases, Lck and Fyn, influences T-cell activation, differentiation, and tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:9–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sefton BM, Taddie JA. Role of tyrosine kinases in lymphocyte activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:372–379. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Takeuchi M, Kuramochi S, Fusaki N, Nada S, Kawamura-Tsuzuku J, Matsuda S, Semba K, Toyoshima K, Okada M, Yamamoto T. Functional and physical interaction of protein-tyrosine kinases Fyn and Csk in the T-cell signaling system. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:27413–27419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Palacios EH, Weiss A. Function of the Src-family kinases, Lck and Fyn, in T-cell development and activation. Oncogene. 2004;23:7990–8000. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Alland L, Peseckis SM, Atherton RE, Berthiaume L, Resh MD. Dual myristylation and palmitylation of Src family member p59fyn affects subcellular localization. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16701–16705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mastick CC, Saltiel AR. Insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of caveolin is specific for the differentiated adipocyte phenotype in 3T3-L1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20706–20714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu J, Deyoung SM, Zhang M, Dold LH, Saltiel AR. The stomatin/prohibitin/flotillin/HflK/C domain of flotillin-1 contains distinct sequences that direct plasma membrane localization and protein interactions in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16125–16134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bull HA, Brickell PM, Dowd PM. Src-related protein tyrosine kinases are physically associated with the surface antigen CD36 in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;351:41–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hunter S, Burton EA, Wu SC, Anderson SM. Fyn associates with Cbl and phosphorylates tyrosine 731 in Cbl, a binding site for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2097–2106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sun XJ, Pons S, Asano T, Myers MG, Jr, Glasheen E, White MF. The Fyn tyrosine kinase binds Irs-1 and forms a distinct signaling complex during insulin stimulation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10583–10587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Wu N, Asara JM, Cantley LC. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a phosphotyrosine-binding protein. Nature. 2008;452:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature06667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sun Y, Ma YC, Huang J, Chen KY, McGarrigle DK, Huang XY. Requirement of SRC-family tyrosine kinases in fat accumulation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14455–14462. doi: 10.1021/bi0509090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cooke MP, Perlmutter RM. Expression of a novel form of the fyn proto-oncogene in hematopoietic cells. New Biol. 1989;1:66–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Goldsmith JF, Hall CG, Atkinson TP. Identification of an alternatively spliced isoform of the fyn tyrosine kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:501–504. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sudol M, Greulich H, Newman L, Sarkar A, Sukegawa J, Yamamoto T. A novel Yes-related kinase, Yrk, is expressed at elevated levels in neural and hematopoietic tissues. Oncogene. 1993;8:823–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]