Abstract

Nej1 is an essential factor in the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway and interacts with the DNA ligase complex, Lif1-Dnl4, through interactions with Lif1. We have mapped K331-V338 in the C-terminal region of Nej1 to be critical for its functionality during repair. Truncation and alanine scanning mutagenesis have been used to identify a motif in Nej1, KKRK (331–334), which is important for both nuclear targeting and NHEJ repair after localization. We have identified F335-V338 to be important for proper interaction with Lif1, however this region is not required for Nej1 recruitment to HO endonuclease-induced DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. Phenylalanine at position 335 is particularly important for the role of Nej1 in repair and the loss of association between Nej1 and Lif1 correlates with a decrease in cell survival upon either transient or continuous HO expression in nej1 mutants.

Keywords: DNA repair, Nej1p, Lif1p, Non-homologous end-joining, double-strand breaks

1. Introduction

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, DSBs can be repaired by homologous recombination (HR), or by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ). NHEJ is conserved in yeast and mammals and requires the core components: Yku70/80 (Ku70/80), Lif1-Dnl4 (XRCC4-DNA ligase IV) and Nej1 (XLF), as well as the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 (MRX) complex in yeast (reviewed in [1]). The initial step in the NHEJ pathway is the localization and binding of the Yku70/80 heterodimer to the DNA double-strand ends. Yku70/80 is crucial for recruitment of additional NHEJ factors to breaks, including the Lif1-Dnl4 complex and Nej1 [2–4].

Lif1-Dnl4 ligates DNA ends [4–8] together and interacts with Nej1 [9–11]. Nej1 stimulates Dnl4 activity [4] and this effect is presumably mediated by the interaction of Nej1 with Lif1, as Nej1 does not directly interact with Dnl4 [9]. The Nej1-Lif1 interaction has been mapped to the N-terminal region of Lif1 (1–157) and the C-terminal region of Nej1 (173–342) [9–11]. The C-terminus of Nej1 also binds DNA, which is important for NHEJ in vivo [12]. Lastly, in response to damage, Nej1 is phosphorylated on S297 and S298 by the Dun1 checkpoint kinase. Phosphorylation at S297/S298 does not affect the Nej1-Lif1 interaction, however it does regulate NHEJ and/or repair by single-strand annealing [13, 14].

Here, we demonstrate that the C-terminal region (CTR) of Nej1 between K330 and V338 is critical for Nej1 localization to the nucleus, for its interaction with Lif1 and for NHEJ repair in vivo. Following recruitment to the site of damage, residues F335-V338 in Nej1 mediate interactions with Lif1 that are critical for repair. The degree of interaction between Lif1 and Nej1, wild type and mutants, correlates with survival following DSB induction, strongly suggesting that Nej1 binding to Lif1-Dnl4 is central for NHEJ.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Yeast strains

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| JC-727 | MATα; hml::ADE hmr::ADE ade3::GAL-HO ade1 leu2-3, 112 lys5 trp1::hisG ura3-52 | JKM179, [34] |

| JC-1280 | MATα leu2::proLEU2-lexAop6 his3 trp1 ura3-52 | [35] |

| JC-1342 | JC-727 with nej1Δ::KanMX6 | MAV015, [36] |

| JC-1687 | JC-727 with nej1-13Myc::trp1 | This study |

| JC-1691 | JC-727 with nej1-(1-330)-13Myc::TRP1 | This study |

| JC-2505 | JC-727 with nej1-(1-334)-13Myc::TRP1 | This study |

| JC-2530 | JC-727 with nej1-(1-335)-13Myc::TRP1 | This study |

| JC-2668 | JC-727 with nej1-(1-338)-13Myc::TRP1 | This study |

| JC-2669 | JC-727 with nej1-(1-336)-13Myc::TRP1 | This study |

| JC-2648 | JC-1342 with nej1 F335A::URA3 | This study |

| JC-2651 | JC-1342 with nej1 G336A::URA3 | This study |

| JC-2655 | JC-1342 with nej1 K337A::URA3 | This study |

| JC-2659 | JC-1342 with nej1 V338A::URA3 | This study |

| JC-2789 | JC-1342 with NEJ1::URA3 | This study |

| JC-2844 | JC-1342 with nej1-F335A/G336A/K337A/V338A::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3133 | JC-2648 with nej1 F335A-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3134 | JC-2844 with nej1 F335A/G336A/K337A/V338A-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3149 | JC-2651 with nej1 G336A-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3159 | JC-2655 with nej1 K337A-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3160 | JC-2659 with nej1 V338A-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3193 | JC-727 with SV40-NLS-NEJ1-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3194 | JC-727 with SV40-NLS-nej1-330-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3209 | JC-2789 with NEJ1-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

| JC-3215 | JC-727 with SV40-NLS-nej1 K331A/K332A/R333A/K334A-13Myc::TRP::URA3 | This study |

All strains except JC-1280 that was used for yeast two-hybrid analysis are derivatives of JKM179.

2.2 Plasmids

A LacZ reporter plasmid, pSH18034, containing lexAgal1-lacZ, was used to monitor protein interactions quantitatively in yeast two-hybrid experiments. Prey vectors were created by the ligation of NEJ1 into pJG4-6 and the bait plasmid was generated by the ligation of LIF1 into pGAL-lexA [15]. Mutants were created by site-directed mutagenesis using Stratagene QuickChange™ mutagenesis. Nej1 integration plasmids were created by ligation of the Nej1 gene sequence along with its endogenous promoter and 3′ untranslated region (UTR) into a pRS306-derived plasmid carrying a URA3 marker. Integration plasmids containing the SV40 NLS were created by PCR of the Nej1 promoter with a reverse primer containing the SV40 NLS sequence. This fragment, a PCR product containing the ORF of Nej1, and a 13-Myc::TRP fragment, with complementary ends were ligated into pRS306 integration plasmid. The SV40 NLS nej1-1 was created by GenScript USA Inc (Piscataway, NJ). Wild type and mutants of Nej1 were reintegrated into the genome of JC-1342 and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

2.3 Media

For experiments with strains containing the galactose inducible HO-endonuclease, cells were grown in YPLGg media consisting of 1% yeast extract, 2% bactopeptone, 2% lactic acid, 3% glycerol and 0.05% glucose. For yeast two-hybrid experiments cells were grown in standard amino acid dropout media lacking histidine, tryptophan and uracil (SC-His/-Trp/-Ura) and containing 2% raffinose as the carbon source.

2.4 Antibodies

Primary antibodies were anti-LexA (mouse; Santa Cruz, 2–12), anti-HA (mouse; Sigma, HA-7), anti-Myc (mouse; Santa Cruz, 9E10), and anti-actin (rabbit; Sigma, A2066). Secondary antibodies were coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Biorad) or to Alexa 594 (goat anti-mouse; Molecular Probes, Eugene) for immunofluorescence.

2.5 Western blotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared by silica bead beating in lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes, 140 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% triton, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete pellet, Roche)). For Nej1-Myc detection, cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C.

2.6 Indirect immunofluorescence

Overnight cultures were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 1h at room temperature (RT). Cells were incubated in SK solution (0.1M KPO4/1.2M sorbitol) containing zymolase (0.4 mg/mL; US Biological) at RT until spheroplasted. Spheroplasted cells were adhered to poly-lysine coated coverslips and treated as described in [16]. Coverslips were blocked with 1% BSA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at RT and then incubated with primary antibody for 1h followed by a 30 min incubation secondary antibody. Coverslips were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI in 1 μg/mL of PBS) and mounted on slides with Vectashield (Vector Labs). Images were obtained on a Leica DMIRE2 fluorescent microscope at 100× magnification (Leica Microsystems Inc.).

2.7 HO endonuclease survival assays

Cell pellets from overnight cultures grown at 25°C in YPAD were washed and resuspended in water. Cells were plated on solid agar YPLG containing either 2% glucose or 2% galactose and incubated at RT for 3–4 days. In transient assays, HO-endonuclease expression was induced in exponentially growing cultures by the addition of galactose. Cultures were incubated for 3h at 30°C. Samples were plated on YPAD at time 0 and after 3h of induction. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 2 days. Survival was calculated relative to uninduced cells. All the survivors that were tested after transient induction were MATα, indicating that their repair was precise.

2.8 Plasmid repair assays

Plasmid repair assays were performed with pRS414 as previously described [12–14]. Briefly, cells were transformed using the standard lithium acetate method with either 10 ng uncut plasmid to correct for transformation efficiency or 0.1 μg XhoI digested plasmid and plated on SC-TRP plates. Cells were grown at 30°C for 3 days. Survival was determined relative to cells expressing wild type Nej1.

2.9 Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and Real-time PCR

ChIP was performed as described in [17] with the addition of a chromatin fractionation step following cell lysis at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. Chromatin pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer before sonication. Nej1-Myc was immunoprecipitated with anti-mouse Dynabeads (Invitrogen) uncoupled or coupled to anti-Myc antibody (mouse; Santa Cruz, 9E10) for 2h at 4°C. Following crosslink reversal, DNA was obtained by phenol/chloroform extraction and precipitated with ethanol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7900 sequence detector system. Reactions contained PerfeCTa qPCR supermix (Quanta Biosciences Inc.), primers and 5′ FAM-labelled/3′ TAMRA labelled probes specific to HO1 (1.6 kb away from cut site), HO2 (0.6 kb away from cut site), HO6 (at the cut site) or SMC2 (control). Enrichment was calculated relative to SMC2 and corrected for cut efficiency, which was determined from the loss of PCR product produced at HO6 after 3h induction compared to time 0 as previously described in [17]

2.10 Yeast two-hybrid assays

Bait and prey plasmids, as well as the reporter plasmid were transformed into JC1280. Transformed cells were grown in SC-His/-Trp/-Ura media containing 2% raffinose overnight and used to inoculate fresh media containing either 2% glucose or 2% galactose. Cultures were grown for 6h at 30°C. β-galactosidase activity was measured in permeabilized cells from induced and uninduced cultures [18].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 The C-terminus of Nej1

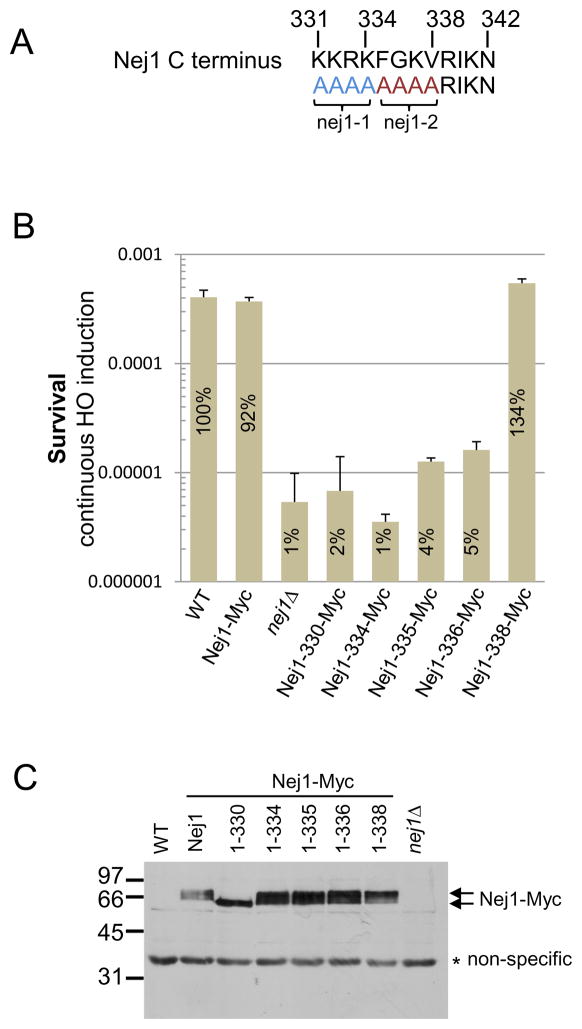

The C-terminus of Nej1 is highly conserved amongst family members (Figs. 1A and S1). To assess the importance of the last 12 amino acids of Nej1 for repair in a physiologically relevant setting, we determined survival upon HO endonuclease induction in a series Nej1-13Myc epitope-tagged truncation mutants (Fig. 1B; [20]). Consistent with previous reports [12, 19, 21, 22], cells lacking NEJ1 exhibited a marked decrease in cell survival (Fig. 1B). The survival of both Nej1-330-Myc and Nej1-334-Myc mutants was similar to nej1Δ cells with a 50 to 100-fold reduction in survival. Nej1-335-Myc and Nej1-336-Myc mutants also exhibited reduced survival, albeit to a lesser degree, however survival of the Nej1-338-Myc truncation appeared similar to, or better than, wild type (Fig. 1B). The addition of a C-terminal Myc epitope did not impact the functionality of full-length Nej1 dramatically, as survival was only slightly reduced compared to the untagged strain (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. The C-terminal region of Nej1 is required for Nej1 function.

(A) The C-terminus of Nej1 (amino acids 331–342) with the products of nej1-1 and nej1-2 mutants indicated. (B) Survival upon continuous expression of the HO-endonuclease in wild type (JC-727), nej1Δ cells (JC-1342), nej1-Myc (JC-1687), nej1-330-Myc (JC-1691), nej1-334-Myc (JC-2505), nej1-335-Myc (JC-2530), nej1-336-Myc (JC-2669), or nej1-338-Myc (JC-2668) cells. Survival was determined by colony number on galactose relative to uninduced cells plated on glucose. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least 3 independent experiments. (C) Western blot analysis from a 12% SDS-PAGE gel with an anti-Myc antibody to detect Nej1 was performed on the indicated strains with a non-specific band serving as a loading control.

The Nej1 truncation proteins expressed at similar levels to wild type ruling out defects attributed to a decrease in protein expression levels (Fig. 1C). Taken together, our data suggest residues between K331 and V338 are critically important for Nej1 function in NHEJ. As previously reported [13], Nej1-Myc displayed a phosphorylation dependent mobility shift (Figs. 1C and S2). With the exception of Nej1-330-Myc, all truncation mutants showed a dramatic shift in mobility that was indicative of phosphorylation. Although Nej1-330-Myc displayed a more subtle shift attributable to phosphorylation, which was only visible on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, its mobility was distinct from wild type and the other mutants (Fig. 1C and S2). It is possible that the Nej1-330-Myc truncation disrupts phosphorylation at S297 or S298, however the C-terminus may direct the phosphorylation of other unidentified site(s) as the mobility shift we detect appeared to be independent of Dun1 kinase and DNA damage, which have been shown previously to be important for phosphorylation at these sites (Fig. S2; [13])

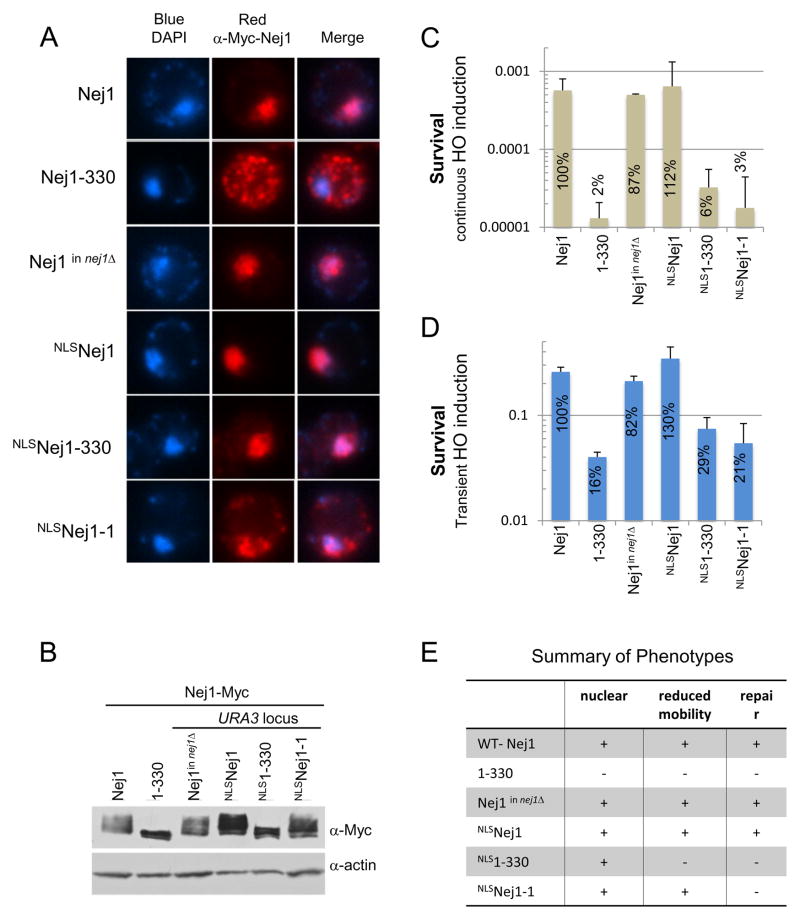

3.2 Nuclear localization and repair with Nej1 NLS mutants

The KKRK motif (331–334) of Nej1 binds DNA [12], however it is also a putative nuclear localization signal, thus we compared the subcellular localization pattern of Nej1 and Nej1-330 by indirect immunoflorescence (Fig. 2A). Full-length Nej1 was primarily nuclear and colocalized with DAPI, however the Nej1-330 truncation displayed a dramatically different pattern, appearing mostly cytoplasmic (Fig. 2A). To artificially target Nej1-330 to the nucleus we generated a fusion with an SV40–NLS. Indeed, localization was restored as the resulting NLSNej1-330 truncation looked indistinguishable from wild type (Fig. 2A). This indicated that the KKRK sequence contributes to Nej1 localization in the nucleus. The phosphorylation pattern of Nej1-330 and NLSNej1-330 looked similar to each other and distinct from wild type (Fig. 2B), therefore targeting Nej1-330 to the nucleus did not seem restore wild type levels of phosphorylation. The influence of the C-terminal region on phosphorylation must be indirect as there are no serine, threonine or tyrosine residues present in the terminal amino acids that are removed in Nej1-330.

Fig. 2. Nej1 KKRK serves as an NLS and is critical for DNA repair.

(A) Indirect immunofluorescence was performed using an anti-Myc antibody to detect Nej1 and DNA was stained with DAPI. (B) Western blot analysis from a 10% SDS-PAGE gel with an anti-Myc antibody was performed to detect Nej1 with actin serving as a loading control. (C) Survival as described in Fig. 1B upon continuous induction of the HO endonuclease or (D) following transient induction of the HO endonuclease where strains were plated on YPAD after a 3h incubation in 2% galactose. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. Values shown indicate percent survival relative to NEJ1. Strains used are Nej1-Myc (JC-1687), Nej1-330-Myc (JC-1691) and Myc-tagged mutants integrated at the URA3 locus of nej1Δ cells including, Nej1-Myc (JC-3209), SV40-NLS-Nej1-Myc (JC-3193), SV40-NLS-Nej1-330-Myc (JC-3194), and SV40-NLS-Nej1-1-Myc (JC-3215). (E) Phenotypic summary of wild type and NLS mutants for nuclear localization in Fig. 2A, reduced mobility/phosphorylation in Fig. 2B, and survival as a measure of repair in Fig. 2C.

When Nej1-330 was targeted to the nucleus, as with NLSNej1-330 (Fig. 2A), there was a slight increase in repair above the truncation alone, however survival remained markedly down (Fig. 2C). Additionally, when we targeted a Nej1 mutant KKRK/AAAA (331–334) to the nucleus by fusion with SV40-NLS, NLSNej1-1 (Fig. 2A), we also observed that survival after damage remained down to the extent of nej1Δ and the 1–330 truncation (Fig. 2C) even as phosphorylation was restored (Figs. 2B and E). This suggests that KKRK (331–334) is important for repair in addition to nuclear targeting [12], but that residues between 334 and 338 are also critical for NHEJ (Figs. 1B and 2C).

The continuous induction of the HO-endonuclease (as in Fig. 1B and 2C) allows for the measurement of imprecise NHEJ as cells are only able to survive and form colonies if they repair the cut site and introduce a mutation into the HO recognition site (or if a mutation is acquired that affects HO-endonuclease expression [24]). To investigate precise NHEJ in these mutants, we transiently induced the HO-endonuclease for 3h at which time we obtain over 95% cut efficiency (data not shown) before plating the cells on YPAD to repress endonuclease expression (Fig 2D; as in [25]). Under these conditions overall cell survival was about 100 times greater than with continuous induction (Fig. 2C and D). The addition of SV40 NLS to wild type Nej1, NLSNej1, resulted in a slight enhancement in survival upon HO induction (Figs. 2C and D), however this might be a result of the protein expression level (Fig. 2B). In general, the same repair patterns during continuous induction were observed with the nej1 mutants upon transient HO induction (Figs. 2C and D). The KKRK motif was previously shown to mediate DNA binding and be required for NHEJ [12] and our results substantiate its importance, but further indicate that this region also serves as a NLS.

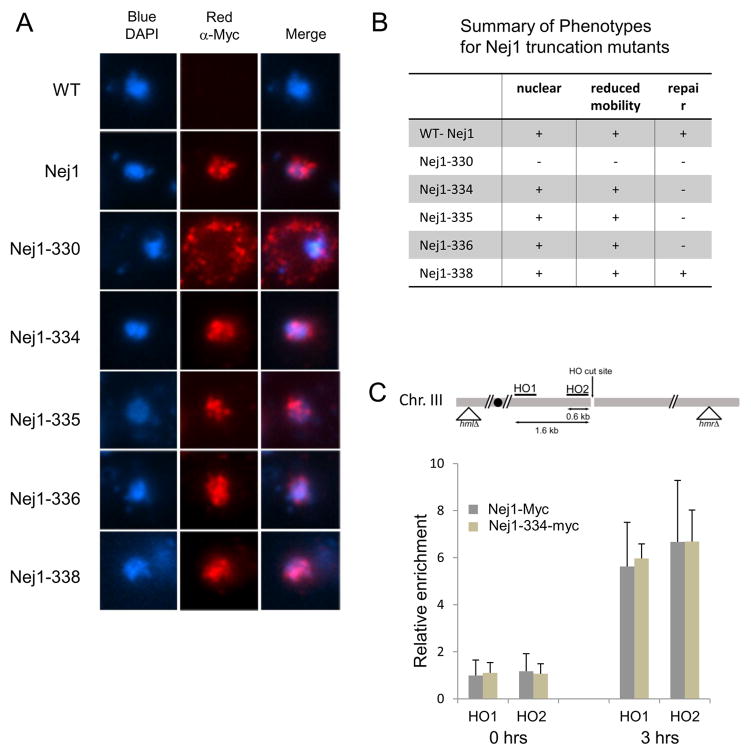

Consistently, nuclear localization was restored in cells harboring the Nej1-334-Myc construct in which the KKRK motif was reintroduced (Figs. 3A, and B). In mammalian cells, the C-terminal 12 amino acids of the Nej1 homolog, XLF, are required for its recruitment to DSBs (Fig. S1; [23]). Thus, to determine whether the repair defect observed for Nej1-334-Myc could be explained by a lack of recruitment to DSBs, we performed ChIP on Nej1-Myc and Nej1-334-Myc at an HO endonuclease-induced DSB (Fig. 3C). After 3 hours of induction, Nej1-Myc and Nej1-334-Myc were similarly recruited to sites 0.6 kb (HO2) and 1.6 kb (HO1) away from the DSB (Fig. 3C). Taken together, our data confirms the importance of the Nej1-CTR for NHEJ in vivo, however, and in contrast to XLF, the CTR of Nej1 beyond 334 is not critical for recruitment to DSBs. This is consistent with the Yku70/80-Nej1 interaction being mediated by the N-terminal region of Nej1 [4].

Fig. 3. The C-terminal region of Nej1 beyond K334 is not required for Nej1 recruitment to DSBs.

(A) Indirect immunofluorescence was performed using an anti-Myc antibody on wild type (JC-727), Nej1-Myc (JC-1687), and Nej1-330-Myc (JC-1691), Nej1-334-Myc (JC-2505), Nej1-335-Myc (JC-2530), Nej1-336-Myc (JC-2669), Nej1-338-Myc (JC-2668) truncation mutants. DNA was stained with DAPI. (B) Phenotypic summary of wild type and truncation mutants for nuclear localization in Fig. 3A, reduced mobility/phosphorylation in Fig. 1C, and survival as a measure of repair in Fig. 1B. (C) Recruitment of Nej1-Myc (JC-1687) and Nej1-334-Myc (JC-2505) to DSBs was determined in ChIP assays. Relative enrichment before (0h) and 3h after HO endonuclease induction was calculated as the PCR signal at HO1 (1.6kb away) or HO2 (0.6kb away) normalized to the signal at a control locus (SMC2) and corrected for cut efficiency. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments.

3.3 Site-direct mutagenesis of Nej1

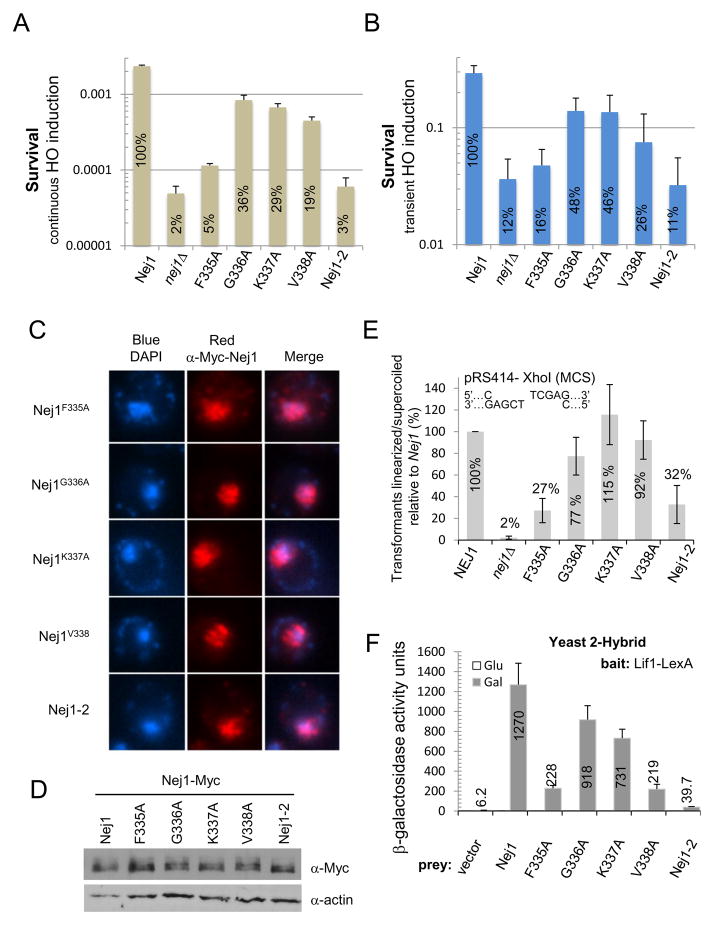

Although nuclear localization, phosphorylation, and recruitment to the site of damage were observed with Nej1-334-Myc (Figs. 1C and 3), this mutant still exhibited defects in NHEJ similar to that of nej1Δ cells, while Nej1-338-Myc supported wild type levels of repair (Fig. 1B). To identify critical residues between F335 and V338 for Nej1 function in NHEJ repair we integrated Nej1 sequences, either wild type or alanine substitution, into the URA3 locus of nej1Δ cells. NEJ1 reintegration restored NHEJ (Fig. 4A and B), however the nej1 mutants, with alanine substitutions at F335, G336, K337 or V338, compromised survival to varying degrees. The most striking defects were seen with F335A and Nej1-2, FGKV/AAAA (335–338), as both mutants approached nej1Δ levels of repair (Fig. 4A and B). The other alanine point mutants at positions G336-V338 displayed significant, but more moderate defects, at 3 to 5-fold below that of wild type NEJ1 upon continuous HO induction (Fig. 4A). During transient HO-endonuclease cutting, the G336A and K337A mutants displayed partial activity with survival at ~50% of wild type. Cells expressing F335A, V338A, or Nej1-2, displayed a repair defect similar to that of nej1Δ cells with less than 30% survival relative to wild type (Fig. 4B). All alanine mutants were expressed and targeted to the nucleus, looking indistinguishable from wild type Nej1 (Figs. 4C and D). We note that overexpression of any one of the mutants in nej1Δ cells partially rescued the loss of viability phenotype and resulted in survival above those levels observed when the mutants were expressed endogenously (Fig. S3A). This suggested the point mutants behaved as hypomorphic alleles rather than exhibiting a dominant negative effect.

Fig. 4. Amino acids 335-338 of Nej1 are important for interactions with Lif1 and Nej1 function.

(A) Survival upon continuous induction of the HO endonuclease or (B) following transient induction of the HO endonuclease where strains were plated on YPAD after a 3h incubation in 2% galactose. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. Values shown indicate percent survival relative to NEJ1. NEJ1 (JC-2789), nej1-F335A (JC-2648), -G336A (JC-2651), -K337A (JC-2655), -V338A (JC-2659), or nej1-2 (JC-2844) driven by the NEJ1 promoter, were integrated at the URA3 locus in nej1Δ cells (JC-1342). (C) Indirect immunofluorescence was performed using an anti-Myc antibody on Nej1-F335A-Myc (JC-3133), Nej1-G336A-Myc (JC-3149), Nej1-K337A-Myc (JC-3159), Nej1-V338A-Myc (JC-3160), and Nej1-2-Myc (JC-3134). DNA was stained with DAPI. (D) Western blot analysis from a 10% SDS-PAGE gel with an anti-Myc antibody was performed to compare expression of the indicated Nej1 mutants with Nej1-Myc (JC-3209) with actin serving as a loading control. (E) Plasmid repair assay with nej1Δ cells (JC-1342) complemented with NEJ1 (JC-2789), nej1-F335A (JC-2648), -G336A (JC-2651), -K337A (JC-2655), -V338A (JC-2659), or nej1-2 (JC-2844). Cells were transformed with undigested or XhoI (5′ overhand, MCS) digested pRS414 before plating on SC-TRP. Error bars indicate standard deviation for three independent experiments. (F) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of the Nej1-Lif1 interaction where β-galactosidase activity was measured in strain JC-1280 transformed with vectors allowing for the expression of LexA-Lif1 as the bait and wild type Nej1 (Nej1), Nej1-F335A, -G336A, -K337A, -V338A or Nej1-2 (FGKV/AAAA) as the prey. Values shown are the average β-galactosidase measurements of three independent experiments and error bars represent the standard deviation.

To further verify the importance of F335-V338 in NHEJ we carried out in vivo plasmid repair assays. Compared to wild type, the G336A mutant showed a mild defect, however the K337A and V338A mutants repaired similarly to NEJ1 (Fig. 4E). The F335A mutant exhibited a 3-fold reduction in end-joining repair (Fig. 4E), which was less severe than the “null-like” defect observed after HO induction (Fig. 4A and B). This allowed us to determine if the individual defects of the alanine mutants were additive. Similar to F335A, the nej1-2 mutant retained some end-joining activity above a complete loss of NEJ1 (Fig. 4E). In all, our results indicate that amino acids F335-V338 of Nej1 are individually important for NHEJ repair in vivo and that F335 is particularly important for Nej1 function.

3.4 Interaction between Lif1 and Nej1 mutants

The primary function of Nej1/XLF is thought to be the stimulation of DNA ligase activity through the interaction of Nej1/XLF with the Lif1/XRCC4-Dnl4/DNA ligase IV complex [4,27]. Mutations in XLF that disrupt XRCC4 binding have been shown to impair NHEJ in vitro and in vivo [28, 30, 31]. However, in yeast the importance of Nej1-Lif1 interactions for repair has not been fully characterized. We reasoned that defects observed with the alanine-scanning mutants were likely subsequent to Nej1 targeting because the Nej1-334-Myc truncation was still recruited to the break site (Fig. 3B). Previously yeast two-hybrid analysis was performed that mapped the interaction between Nej1 and Lif1 to be between the C-terminus of Nej1 and the N-terminus of Lif1 [9, 10, 11], thus we utilized this approach for consistency and to obtain quantitative measurements for interactions between Lif1 and Nej1, wild type and mutants.

Wild type Nej1 or alanine point mutants were expressed as HA-tagged prey and LexA-tagged Lif1, was the bait. All Nej1 proteins expressed at similar levels (Fig. S3B) and exhibited interaction with Lif1, however none interacted to the level of wild type Nej1 (Fig. 4F). G336A and K337A displayed a 20–40% decrease in their interactions with Lif1 while the F335A and V338A mutants displayed the most dramatic defects with an ~80% reduction (Fig. 4F). The level of Lif1 interaction with the different Nej1 mutants correlated to the level of survival observed for cells expressing these mutants following HO-endonuclease induction (Figs. 4A and B). Although we cannot rule out additional functionality for the F335-V388 region of Nej1 during repair, one primary function appears to be in mediating interaction with Lif1.

3.5 Conclusions

In conclusion, Nej1 and its mammalian homolog XLF are required for efficient NHEJ both in vitro and in vivo (reviewed in [1, 32]). Here we define residues in the C-terminus of Nej1 that are critical for nuclear localization, interaction with its binding partner, Lif1, and NHEJ. Similar to the interaction between XLF and XRCC4, our work supports the hypothesis that Nej1 binding to Lif1 is essential for efficient NHEJ in vivo. While the N-terminal regions of XLF and XRCC4 interact, it is the CTR of Nej1 that interacts with Lif1. Thus, our results help explain the difference between the CTR of mammalian XLF, which is not necessary for NHEJ or V(D)J recombination in vivo [33], and the CTR of yeast Nej1, which is critical for NHEJ-mediated repair.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Nej1-CTR in essential for NHEJ-mediated DNA repair

Residues K331-K334 serve as a nuclear localization signal in Nej1

F335 is critical for interactions with Lif1 and NHEJ

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Denise Bustard for initially constructing the Nej1 integration vector and JE Haber for yeast strains. BLM was supported by graduate studentships from NSERC and AHFMR/Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions. This work was supported by Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (JC and SPLM), operating grants from CIHR (MOP-82736 to JC and MOP-13639 to SPLM), NSERC (418122 to JC), National Institutes of Health, Structural Cell Biology of DNA Repair Machines P01 Grant CA92584 (SPLM). Additional support was provided from the Engineered Air Chair in Cancer Research (SPLM). SPLM is a professor of the Killam Trust.

Abbreviations

- CTR

C-terminal region

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DSBs

double-strand breaks

- NHEJ

non-homologous end-joining

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Daley JM, Palmbos PL, Wu D, Wilson TE. Nonhomologous end joining in yeast. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:431–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.113340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu D, Topper LM, Wilson TE. Recruitment and dissociation of nonhomologous end joining proteins at a DNA double-strand break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;178:1237–1249. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmbos PL, Wu D, Daley JM, Wilson TE. Recruitment of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dnl4-Lif1 complex to a double-strand break requires interactions with Yku80 and the Xrs2 FHA domain. Genetics. 2008;180:1809–1819. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.095539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X, Tomkinson AE. Yeast Nej1 is a key participant in the initial end binding and final ligation steps of nonhomologous end joining. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4931–4940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.195024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teo SH, Jackson SP. Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA ligase IV: involvement in DNA double-strand break repair. EMBO J. 1997;16:4788–4795. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schar P, Herrmann G, Daly G, Lindahl T. A newly identified DNA ligase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in RAD52-independent repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Genes & Development. 1997;11:1912–1924. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson TE, Grawunder U, Lieber MR. Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining. Nature. 1997;388:495–498. doi: 10.1038/41365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrmann G, Lindahl T, Schar P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae LIF1: a function involved in DNA double-strand break repair related to mammalian XRCC4. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:4188–4198. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande RA, Wilson TE. Modes of interaction among yeast Nej1, Lif1 and Dnl4 proteins and comparison to human XLF, XRCC4 and Lig4. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1507–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank-Vaillant M, Marcand S. NHEJ regulation by mating type is exercised through a novel protein, Lif2p, essential to the ligase IV pathway. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3005–3012. doi: 10.1101/gad.206801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ooi SL, Shoemaker DD, Boeke JD. A DNA microarray-based genetic screen for nonhomologous end-joining mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2001;294:2552–2556. doi: 10.1126/science.1065672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulek M, Yarrington R, McGibbon G, Boeke JD, Junop M. A critical role for the C-terminus of Nej1 protein in Lif1p association, DNA binding and non-homologous end-joining. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1805–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahnesorg P, Jackson SP. The non-homologous end-joining protein Nej1p is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter SD, Vigasova D, Chen J, Chovanec M, Astrom SU. Nej1 recruits the Srs2 helicase to DNA double-strand breaks and supports repair by a single-strand annealing-like mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12037–12042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903869106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aushubel FM, Brent R, Kinston R, Moore D, Seidman JJ, Smith J, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotta M, Laroche T, Gasser SM. Analysis of nuclear organization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods in Enzymology. 1999;304:663–672. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Attikum H, Fritsch O, Hohn B, Gasser SM. Recruitment of the INO80 complex by H2A phosphorylation links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling with DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2004;119:777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams A, Gottschling DE, Kaiser CA, Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavero S, Chahwan C, Russell P. Xlf1 is required for DNA repair by nonhomologous end joining in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2007;175:963–967. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.067850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SE, Moore JK, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner RD, Haber JE. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kegel A, Sjostrand JO, Astrom SU. Nej1p, a cell type-specific regulator of nonhomologous end joining in yeast. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1611–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valencia M, Bentele M, Vaze MB, Herrmann G, Kraus E, Lee SE, Schar P, Haber JE. NEJ1 controls non-homologous end joining in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2001;414:666–669. doi: 10.1038/414666a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yano K, Morotomi-Yano K, Lee KJ, Chen DJ. Functional significance of the interaction with Ku in DNA double-strand break recognition of XLF. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:841–846. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore JK, Haber JE. Cell cycle and genetic requirements of two pathways of nonhomologous end-joining repair of double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2164–2173. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SE, Paques F, Sylvan J, Haber JE. Role of yeast SIR genes and mating type in directing DNA double-strand breaks to homologous and non-homologous repair paths. Current Biology. 1999;9:767–770. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L, Trujillo K, Ramos W, Sung P, Tomkinson AE. Promotion of Dnl4-catalyzed DNA end-joining by the Rad50/Mre11/Xrs2 and Hdf1/Hdf2 complexes. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riballo E, Woodbine L, Stiff T, Walker SA, Goodarzi AA, Jeggo PA. XLF-Cernunnos promotes DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 re-adenylation following ligation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:482–492. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andres SN, Modesti M, Tsai CJ, Chu G, Junop MS. Crystal structure of human XLF: a twist in nonhomologous DNA end-joining. Mol Cell. 2007;28:1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Chirgadze DY, Bolanos-Garcia VM, Sibanda BL, Davies OR, Ahnesorg P, Jackson SP, Blundell TL. Crystal structure of human XLF/Cernunnos reveals unexpected differences from XRCC4 with implications for NHEJ. EMBO J. 2008;27:290–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malivert L, Ropars V, Nunez M, Drevet P, Miron S, Faure G, Guerois R, Mornon JP, Revy P, Charbonnier JB, Callebaut I, de Villartay JP. Delineation of the Xrcc4-interacting region in the globular head domain of cernunnos/XLF. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26475–26483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.138156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy S, Andres SN, Vergnes A, Neal JA, Xu Y, Yu Y, Lees-Miller SP, Junop M, Modesti M, Meek K. XRCC4’s interaction with XLF is required for coding (but not signal) end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1684–1694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahaney BL, Hammel M, Meek K, Tainer JA, Lees-Miller SP. XRCC4 and XLF form long helical protein filaments suitable for DNA end protection and alignment to facilitate DNA double strand break repair. Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;19 doi: 10.1139/bcb-2012-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malivert L, Callebaut I, Rivera-Munoz P, Fischer A, Mornon JP, Revy P, de Villartay JP. The C-terminal domain of Cernunnos/XLF is dispensable for DNA repair in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1116–1122. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01521-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SE, Moore JK, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner RD, Haber JE. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golemis EA, Gyuris J, Brent R. Interaction Trap/ Two Hybrid System to Identify Interacting Proteins. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocals in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1996. pp. 20.21.21–20.21.23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valencia M, Bentele M, Vaze MB, Herrmann G, Kraus E, Lee SE, Schar P, Haber JE. NEJ1 controls non-homologous end joining in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2001;414:666–669. doi: 10.1038/414666a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.