Observational studies increasingly argue for the growing equipoise of using stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) in high-risk patient subgroups of stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This model adds to this literature by considering cost-effectiveness and the implications of both health and cost on a publicly funded health care system at the national level. The use of SABR for NSCLC in Canada is projected to result in significant cost savings and survival gains.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, Cost-effectiveness, Microsimulation model, Health policy

Abstract

Background.

The Cancer Risk Management Model (CRMM) was used to estimate the health and economic impact of introducing stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) for stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in Canada.

Methods.

The CRMM uses Monte Carlo microsimulation representative of all Canadians. Lung cancer outputs were previously validated internally (Statistics Canada) and externally (Canadian Cancer Registry). We updated costs using the Ontario schedule of fees and benefits or the consumer price index to calculate 2013 Canadian dollars, discounted at a 3% rate. The reference model assumed that for stage I NSCLC, 75% of patients undergo surgery (lobectomy, sublobar resection, or pneumonectomy), 12.5% undergo radiotherapy (RT), and 12.5% undergo best supportive care (BSC). SABR was introduced in 2008 as an alternative to sublobar resection, RT, and BSC at rates reflective of the literature. Incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated; a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 (all amounts are in Canadian dollars) per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) was used from the health care payer perspective.

Results.

The total cost for 25,085 new cases of lung cancer in 2013 was calculated to be $608,002,599. Mean upfront costs for the 4,318 stage I cases were $7,646.98 for RT, $8,815.55 for SABR, $12,161.17 for sublobar resection, $16,266.12 for lobectomy, $22,940.59 for pneumonectomy, and $14,582.87 for BSC. SABR dominated (higher QALY, lower cost) RT, sublobar resection, and BSC. RT had lower initial costs than SABR that were offset by subsequent costs associated with recurrence. Lobectomy was cost effective when compared with SABR, with an ICER of $55,909.06.

Conclusion.

The use of SABR for NSCLC in Canada is projected to result in significant cost savings and survival gains.

Implications for Practice:

SABR is increasingly being used in stage I NSCLC patients with varying levels of comorbidities. In this study, we measure the financial and health impact of introducing SABR for stage I NSCLC in Canada. While SABR is cost-effective for medically inoperable and borderline operable patients, lobectomy is preferred for those who are eligible. The use of SABR is thus projected to result in significant cost and survival gains at the population level.

Introduction

Lung cancer continues to be the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Despite this dismal prognosis, early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is potentially curable, with 5-year overall survival approaching 50% [2]. The standard of care for these patients is resection; however, approximately 25% of patients are unfit for surgery because of advanced age and/or comorbid illness [3]. In addition, alternative treatment with conventional radiotherapy (RT) is associated with poor local control and low overall survival rates [4]. Given the marginal benefit of conventional RT over best supportive care (BSC), a significant proportion of patients remains untreated, even in the modern era [5].

As a convenient treatment option delivered over a few fractions with low morbidity, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) has changed the landscape for the otherwise medically inoperable stage I NSCLC patient [6]. Local control rates are in excess of 90% and appear to be generalizable across various fractionating schemes and delivery platforms [7, 8]. Given the success of SABR in the medically inoperable patient, other indications in stage I NSCLC are active areas of research. For operable patients, propensity score-matched analyses demonstrate similar survival and recurrence outcomes for SABR and surgery [9]. In addition, SABR is increasingly being used in patients with a solitary pulmonary nodule without pathologic confirmation of lung cancer, particularly in frail patients for whom the risks of biopsy are high [7, 10]. This strategy appears to be justified in areas in which the diagnosis of benign disease is low and validated models exist to calculate the likelihood of malignancy [11, 12]. The use of SABR for these and other indications has had an important clinical impact because its introduction is correlated with improved overall survival for stage I NSCLC at the population level [13, 14].

The anticipated rises in incidence of early lung cancer and the indications of SABR have tremendous ramifications on the demand for health care resources in any payer system. In the absence of randomized data, comparative effectiveness research evaluating the role of SABR in stage I NSCLC takes on greater importance to assess the relative clinical and cost implications at a population level. The goal of this project is to determine the cost-effectiveness of SABR for various scenarios in stage I NSCLC in the context of the publically funded Canadian health care system.

Materials and Methods

The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) was established in 2007 by the Canadian government to create a national cancer control plan. CPAC subsequently developed the Cancer Risk Management Model (CRMM), a Web-enabled platform (http://www.cancerview.ca) that allows researchers to simulate the impact of different oncologic health policies such as risk factor modification, screening interventions, and new treatment modalities for common malignancies. The relative merits of these strategies can be analyzed by forecasting their influence on cancer incidence, mortality, costs, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), and accordingly, cost-effectiveness. This is achieved through discrete-event, continuous-time, Monte Carlo microsimulation of millions of individual biographies of all Canadians from birth to death.

Details regarding the development of the CRMM module for lung cancer have been described previously [15, 16]. Briefly, lung cancer incidence is determined in part by cumulative smoking and radon exposure [17]. In the model, patients are evaluated by their family physician and referred for investigation by a specialist, after which stage- and histology-appropriate treatment is initiated. The proportion of patients receiving alternative treatments due to advanced age, comorbidity, and/or poor performance status are informed by provincial patterns of practice [18]. Survival by stage and histology were extracted from a review of the medical literature, and follow-up procedures were conducted in accordance with published provincial guidelines [18].

The model was previously validated internally using Statistics Canada data and externally with Canadian Cancer Registry data to ensure that all demographics, economics, risk factors, incidence of cancer, and oncologic outcomes reflected observed levels in the Canadian population before 2007 [16]. In the present study, professional fees were obtained from the most recent edition of the Ontario schedule of fees and benefits (http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/). Other direct and indirect health care costs abstracted in the previous version of the CRMM model were adjusted to reflect 2013 Canadian dollars using the consumer price index from the Bank of Canada. A 10-year time horizon was used, and both costs and QALYs were discounted at a 3% rate.

A QALY is a health outcome measure that takes into account both the quantity and quality of life. The preference score for the quality of life associated with a health state is referred to as a “utility” and ranges from 1 (full health) to 0 (death). The Classification and Measurement System of Functional Health, which assess functional capacity over 11 health domains, was used to assign utility scores derived by Statistics Canada for various stage-specific lung cancer health states at diagnosis, treatment, remission, recurrence, and end of life [19, 20].

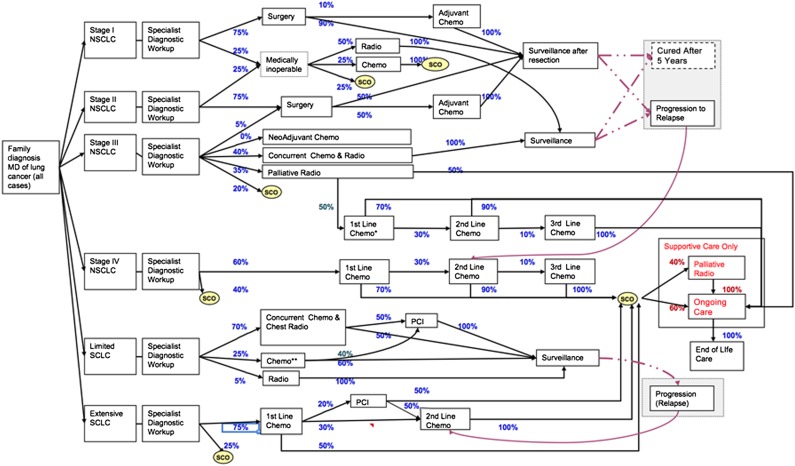

A schematic of the management algorithm used by the CRMM (version 2.0) for lung cancer is depicted in Figure 1. In this reference version of the model, it was assumed that for stage I NSCLC, 75% of patients would undergo surgical resection, with the remaining patients receiving either conventional RT or BSC. The proportions of surgical procedures performed were lobectomy (66%), sublobar resection (i.e., wedge resection; 33%), and pneumonectomy (1%). Although there is growing interest in the role of segmentectomy in stage I NSCLC [21], sublobar resection in the reference version of the current CRMM model was programmed exclusively to reflect cost and clinical outcomes related to wedge resection only. To evaluate the impact of the introduction of SABR in the Canadian population starting in 2008, three scenarios were evaluated. Initially, SABR was modeled to replace conventional RT. Then, SABR was introduced as a treatment option for previously untreated patients, modeled after a Dutch population-based time-trend analysis in which the proportion of untreated patients decreased by 25% [13]. Finally, SABR was evaluated as an alternative treatment option for surgical patients undergoing either sublobar resection or lobectomy.

Figure 1.

Schema of the lung cancer module of the Cancer Risk Management Model version 2.0.

Abbreviations: **, Some may get second line chemo and palliative radio at recurrence; Chemo, chemotherapy; MD, medical doctor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PCI, prophylactic cranial irradiation; Radio, radiotherapy; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; SCO, supportive care only.

Two-piece Weibull distributions were developed in the initial CRMM to predict for stage- and treatment-specific recurrence and overall survival parameters. Weibull distributions model increasing, decreasing, or constant failure rates to produce estimates of survival and, accordingly, are commonly used in health technology assessment [22]. The same methods were used to generate outcomes related to SABR for the three scenarios described. To model outcomes for SABR patients who previously received no treatment or conventional RT, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 0236 multi-institutional SABR trial was used [8]. Because outcomes from RTOG 0236 extend to only 3 years, individual patient data from the VU University, an institution with one of the largest experiences with SABR in stage I NSCLC, were used as supplementation to predict for more long-term results [10]. Potentially operable patients treated with SABR from the same database were used to model outcomes related to SABR patients who initially received either surgery or sublobar resection [23].

For each scenario, an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated by dividing the incremental costs associated with SABR by the incremental QALYs gained. A willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per QALY gained (all amounts are in Canadian dollars) was used to determine whether each potential indication for SABR was cost effective from the Canadian health care payer perspective.

Results

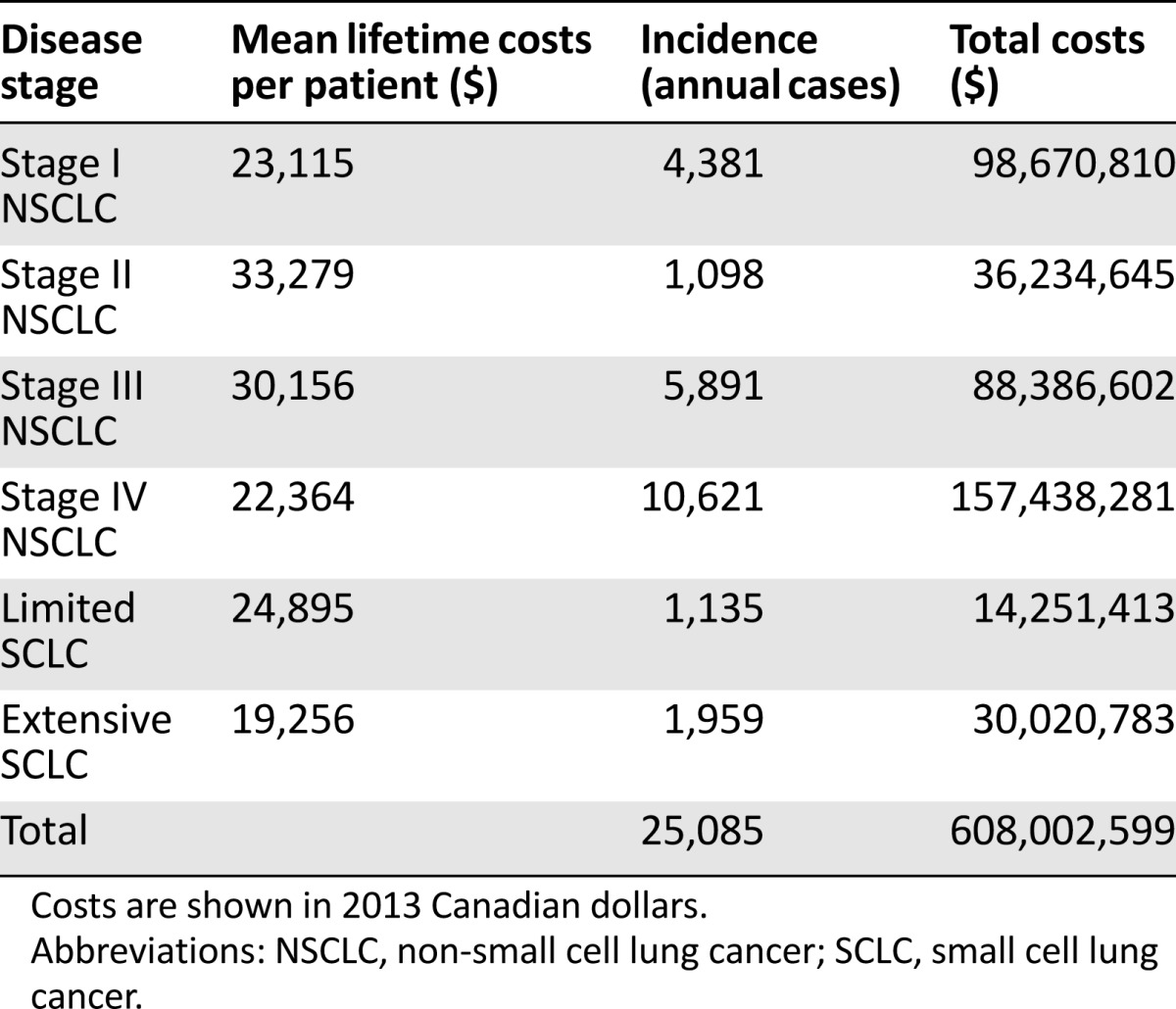

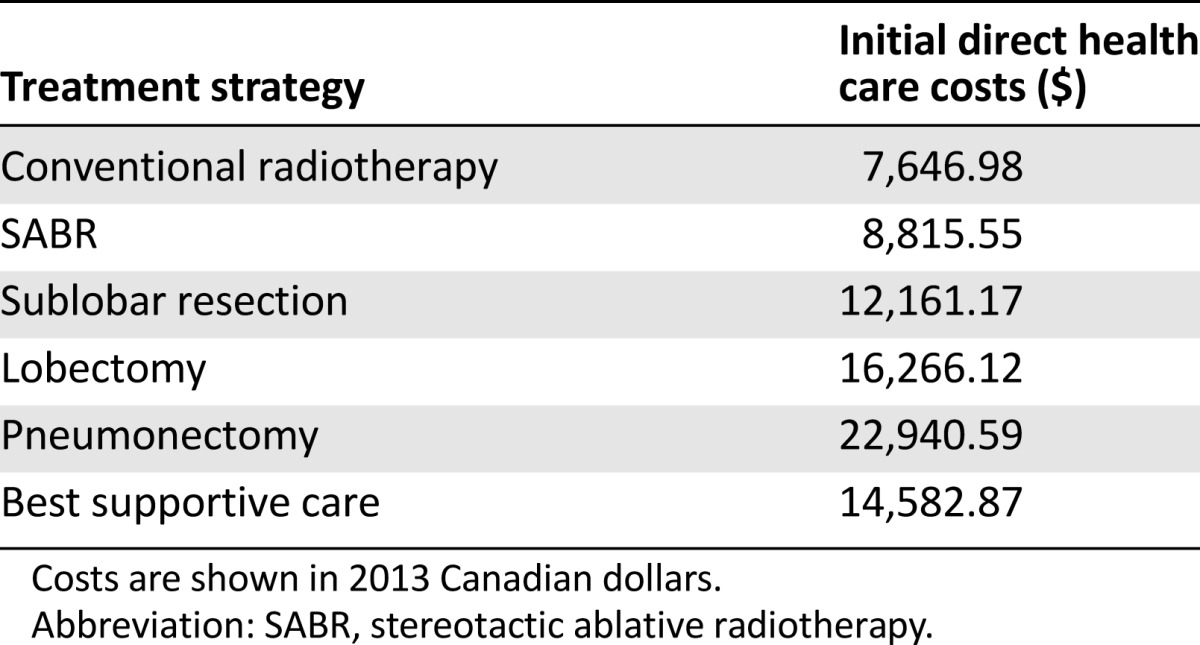

The model predicted for 25,085 new cases of lung cancer in Canada in 2013, of which 4,381 were forecast to be stage I NSCLC. In the reference case, total lifetime costs associated with the management and treatment of all lung cancers in this year were $608,002,599. Anticipated stage-specific total and mean individual lifetime costs as well as incidence for this year are summarized in Table 1. Table 2 summarizes the mean upfront costs per case for the 4,318 stage I cases: RT, $7,646.98; SABR, $8,815.55; sublobar resection, $12,161.17; lobectomy, $16,266.12; pneumonectomy, $22,940.59; and BSC, $14.582.87. Although RT was associated with lower upfront costs when compared with SABR, this was offset by subsequent costs associated with recurrence.

Table 1.

Lifetime costs of lung cancer by stage of disease and total costs for cases diagnosed in 2013

Table 2.

Initial direct health care costs per case for stage I non-small cell lung cancer costs stratified by treatment

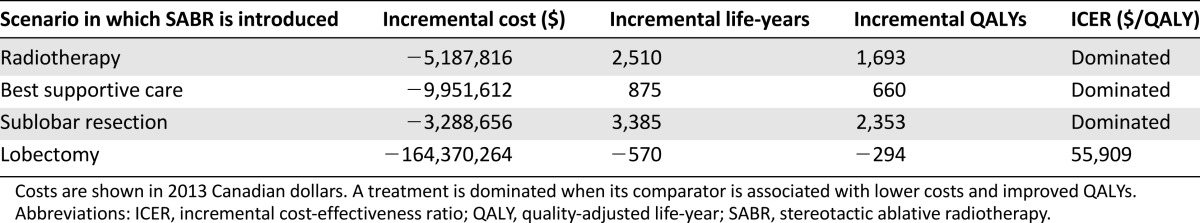

When compared with SABR, conventional RT, sublobar resection, and BSC were dominated (i.e., were more expensive and produced lower QALYs [Table 3]). Lobectomy was cost effective when compared with SABR, producing more QALYs but at a higher cost, with an ICER of $55,909.06.

Table 3.

Cost-effectiveness of SABR

The implementation of SABR for the three cost-effective indications resulted in average savings of $18,190,729.40 per year between 2008 and 2017 (conventional RT, $5,127,645; sublobar resection, $9,745,432.80; BSC, $3,317,651.60). From a clinical perspective, the use of SABR prevented 566.2 deaths from lung cancer per year, with an average annual gain of 8663.6 life-years or 5,979.6 QALYs.

Discussion

This model indicates that in a population of approximately 35 million Canadians, SABR was the most cost-effective treatment modality for medically inoperable and borderline operable stage I NSCLC, dominating conventional RT, BSC, and sublobar resection. For operable patients, lobectomy was considered to be the preferred treatment, with an ICER of $55,909.06 over SABR. Adhering to these cost-effect measures over a 10-year period would result in potential savings of nearly $200 million, a gain of tens of thousands of life years, and avoidance of more than 5,000 deaths from lung cancer. The majority of the cost savings and survival improvements are due to the use of SABR in patients who would otherwise be left untreated. In the CRMM, BSC is more costly than SABR because the former is calculated as an aggregate cost of all aspects of care related to the final 3 months of life in a typical NSCLC patient (including a proportion of patients who are hospitalized), informed by provincial data [24].

Because radiotherapy in Canada is provided through publicly funded cancer centers where market forces have limited influence on costing, these findings can serve as a benchmark for policy makers worldwide in any payer system.

Lobectomy is widely considered to be the treatment of choice for stage I NSCLC patients who are medically fit; direct randomized comparisons with SABR are unavailable. This is not due to a lack of international effort to obtain such data: only 68 of the combined target of 2,410 patients were ever enrolled in three phase III randomized controlled trials; all closed due to poor accrual [25, 26]. Although the present model, among others [27], determined that lobectomy was the most cost-effective option for stage I NSCLC, several other comparative effectiveness studies argue for treatment equivalence in this setting [28]. A propensity-matched population-based analysis using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare (SEER-Medicare) database, for example, suggested that although long-term survival rates did not differ between SABR and surgery, short-term mortality is improved at <1% versus 4%, respectively [29]. A Markov model previously published by our group indicated that the overall survival benefit of lobectomy over SABR disappeared when postoperative mortality rates increased beyond 3% [30]. Although the present study is unable to confirm these findings because the CRMM does not allow for deterministic sensitivity analysis of this parameter, a contemporaneous review of patients with stage I NSCLC (with varying levels of comorbidity but fit for operation) who underwent surgery revealed 90-day postoperative mortality rates that ranged from 1.1% to 9.5% [31]. Centralization of surgical resections to high-volume centers does not appear to reduce postoperative mortality rates [32], and in higher risk patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a systematic review found the 30-day mortality rate following surgery to be 10% (range: 7%–25%) and 0% following SABR [33]. Although these borderline-operable patients may represent a minority of all surgical stage I NSCLC patients, initial mortality risk is a factor that patients and physicians should consider when choosing a treatment strategy, even if there may be a survival benefit with lobectomy over SABR. This is especially true because risk-averse patients have been shown to be hesitant to choose the strategy that involves an increased risk of death in the near future [34].

Our model assumes that the use of SABR, instead of conventional RT, in stage I NSCLC translates into improvement of overall survival. Although this finding has not been demonstrated in a prospective trial, other forms of comparative effectiveness research, including a population-based propensity-score matched analysis of the SEER-Medicare database, indicate that patients with stage I NSCLC who were treated with SABR had improved local control rates compared with their conventional RT counterparts, leading to improvement in overall survival [29]. Biologically, this hypothesis of an association between higher local control and overall survival rates from RT is certainly plausible and has been demonstrated by meta-analyses and randomized trials in breast, prostate, and head and neck cancers [35]. As results from at least three randomized controlled trials evaluating SABR versus conventional RT are awaited [36], the overwhelming evidence in the interim suggests that radiation at biological effective doses below 100 Gy should be used with caution [37].

Additional conclusions of our study are in keeping with other decision analytic models evaluating the use of SABR in NSCLC. Sher et al. compared SABR with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for the medically inoperable stage I NSCLC patient from the Medicare perspective [38]. This American study found that ICER (in U.S. dollars) for SABR over 3D-CRT was $6,000/QALY, and the ICER for SABR over RFA was $14,100/QALY, conclusions that were robust over a series of one-way sensitivity analyses as well as probabilistic sensitivity analyses of local control rates and utilities. Grutters et al. similarly determined that SABR is more cost effective compared with 3D-CRT for medically inoperable stage I NSCLC in the Dutch setting [39]. This study also explored the value of pursuing research in more costly particle-based carbon ion and proton therapies. The latter was dominated by both carbon ions and SABR. Although carbon-ion therapy was cost effective, assuming a ceiling ratio of €80,000/QALY, the certainty of the decision to implement this modality over SABR as the standard treatment for medically inoperable stage I NSCLC nationally was marginally better than the flip of a coin (52% vs. 48%). Our study also found that SABR was cost effective when compared with wedge resection, analogous to the findings of an American cost-effectiveness analysis [27]. This study, much like our analysis (due to technical factors related to how the CRMM was coded), did not directly consider segmentectomy as a treatment option. A future Markov model to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of segmentectomy in stage I NSCLC is being planned.

The CRMM projection of the future rise in the incidence of stage I NSCLC in Canada was based primarily on an anticipated shift in demographics in an aging population. Such an increase does not account for the potential implementation of low-dose computed tomography screening. In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) reported a 20% reduction in mortality from lung cancer when compared with chest x-ray [40]. Although this landmark study has led several organizations to recommend [41] or suggest [42] that physicians offer screening to individuals at high risk for lung cancer, results from the Pan-Canadian CT screening trial are awaited to determine generalizability of the NLST’s findings in a Canadian population [43]. This, and most other low-dose CT screening trials, use surgery for suspected or confirmed lung cancer [44]. The Dutch-Belgian lung cancer screening trial (NELSON), however, allowed for the use of high-dose radiotherapy in patients with a growing solitary pulmonary nodule without a histologic diagnosis. Experts have argued that an 85% likelihood of malignancy is the threshold for treatment without prior pathology [45]. In a practical step, the Pan-Canadian study has developed a predictive tool to calculate likelihood of malignancy, based on patient and nodule characteristics for patients screened with low-dose CT, that can be accessed through online calculators [43]. Ultimately, if CT screening is implemented, it is foreseeable that the use of SABR will increase in parallel with the even faster increase in stage I NSCLC cases, thereby leading to additional cost savings and QALY gains over those projected by this study.

The conclusions of this study must be considered in the context of both strengths and limitations. The CRMM was built with rigorous internal and external validation of population-based lung cancer parameters in Canada before 2007; however, like any model, limitations are inherent where key assumptions are made. We assumed that SABR was implemented uniformly across the country for each cost-effective indication in the 2008 calendar year because the CRMM does not allow for differential uptake by province. This year was chosen because a Canadian pattern of practice survey indicated that SABR was available for lung cancer at only 1 of 41 cancer centers before 2008 and was more widely available to 90% of the entire population by 2011 [46]. Because the lung cancer module of the CRMM was initially constructed with the intent to evaluate CT screening and chemotherapeutic modalities, this feedback has been relayed to CPAC so that such analyses may be available for future radiation oncology evaluations.

Conclusion

Observational studies increasingly argue for the growing equipoise of using SABR in high-risk patient subgroups of stage I NSCLC. This model adds to this literature by considering cost-effectiveness and the implications of both health and cost on a publically health care funded system at the national level. Although lobectomy was found to be the most cost-effective treatment overall, studies are ongoing to determine the most appropriate treatment for fit patients. Ultimately, although the findings of this modeling study are in keeping with published data, individual patient decision making should be shared with the patient and the multidisciplinary team.

Acknowledgments

We thank Natalie Fitzgerald from the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer and Bill Flanagan from Statistics Canada for their technical support in using the Cancer Risk Management Model. A.V.L. is the 2013 recipient of the CARO-Elekta Research Fellowship and was awarded the 2014 Detweiler Travelling Fellowship from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. A.V.L. and D.A.P. received the Western University International Research Award to support this work. The VU University Medical Center has a research agreement with Varian Medical Systems. This analysis is based on the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer’s Cancer Risk Management Model. The Cancer Risk Management Model has been made possible through a financial contribution from Health Canada, through the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The assumptions and calculations underlying the simulation results were prepared by the London Regional Cancer Program and the VU University Medical Center, and the responsibility for the use and interpretation of these data is entirely that of the authors.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Alexander V. Louie, George B. Rodrigues, David A. Palma, Suresh Senan

Provision of study material or patients: Alexander V. Louie, David A. Palma, Suresh Senan

Collection and/or assembly of data: Alexander V. Louie

Data analysis and interpretation: Alexander V. Louie, George B. Rodrigues, David A. Palma, Suresh Senan

Manuscript writing: Alexander V. Louie, George B. Rodrigues, David A. Palma, Suresh Senan

Final approval of manuscript: Alexander V. Louie, George B. Rodrigues, David A. Palma, Suresh Senan

Disclosures

Alexander V. Louie: Varian Medical Systems (RF); Suresh Senan: Varian Medical Systems (RF, H); Lilly Oncology (SAB). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rami-Porta R, Crowley JJ, Goldstraw P. The revised TNM staging system for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;15:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cykert S, Dilworth-Anderson P, Monroe MH, et al. Factors associated with decisions to undergo surgery among patients with newly diagnosed early-stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:2368–2376. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wisnivesky JP, Bonomi M, Henschke C, et al. Radiation therapy for the treatment of unresected stage I-II non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:1461–1467. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vest MT, Herrin J, Soulos PR, et al. Use of new treatment modalities for non-small cell lung cancer care in the Medicare population. Chest. 2013;143:429–435. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirvani SM, Chang JY, Roth JA. Can stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in early stage lung cancers produce comparable success as surgery? Thorac Surg Clin. 2013;23:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guckenberger M, Allgäuer M, Appold S, et al. Safety and efficacy of stereotactic body radiotherapy for stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer in routine clinical practice: A patterns-of-care and outcome analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:1050–1058. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318293dc45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1070–1076. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varlotto J, Fakiris A, Flickinger J, et al. Matched-pair and propensity score comparisons of outcomes of patients with clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer treated with resection or stereotactic radiosurgery. Cancer. 2013;119:2683–2691. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senthi S, Lagerwaard FJ, Haasbeek CJ, et al. Patterns of disease recurrence after stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for early stage non-small-cell lung cancer: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:802–809. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herder GJ, van Tinteren H, Golding RP, et al. Clinical prediction model to characterize pulmonary nodules: Validation and added value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Chest. 2005;128:2490–2496. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verstegen NE, Oosterhuis JW, Palma DA, et al. Stage I-II non-small-cell lung cancer treated using either stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) or lobectomy by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS): Outcomes of a propensity score-matched analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1543–1548. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haasbeek CJ, Palma D, Visser O, et al. Early-stage lung cancer in elderly patients: A population-based study of changes in treatment patterns and survival in the Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2743–2747. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palma D, Visser O, Lagerwaard FJ, et al. Impact of introducing stereotactic lung radiotherapy for elderly patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: A population-based time-trend analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5153–5159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans WK, Wolfson MC, Flanagan WM, et al. Canadian Cancer Risk Management Model: Evaluation of cancer control. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29:131–139. doi: 10.1017/S0266462313000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans WK, Wolfson MC, Flanagan WM, et al. The evaluation of cancer control interventions in lung cancer using the Canadian Cancer Risk Management Model. Lung Cancer Manage. 2012;1:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittemore AS, McMillan A. Lung cancer mortality among U.S. uranium miners: A reappraisal. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;71:489–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans WK, Ung YC, Assouad N, et al. Improving the quality of lung cancer care in Ontario: The lung cancer disease pathway initiative. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:876–882. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828cb548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIntosh CN, Connor Gorber S, Bernier J, et al. Eliciting Canadian population preferences for health states using the Classification and Measurement System of Functional Health (CLAMES) Chronic Dis Can. 2007;28:29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans WK, Connor Gorber SK, Spence ST, et al. Health state descriptors for Canadians: Cancers. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith CB, Kale M, Mhango G, et al. Comparative outcomes of elderly stage I lung cancer patients treated with segmentectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus open resection. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:383–389. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heitjan DF, Kim CY, Li H. Bayesian estimation of cost-effectiveness from censored data. Stat Med. 2004;23:1297–1309. doi: 10.1002/sim.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagerwaard FJ, Verstegen NE, Haasbeek CJ, et al. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in patients with potentially operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navaratnam S, Kliewer EV, Butler J, et al. Population-based patterns and cost of management of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after completion of chemotherapy until death. Lung Cancer. 2010;70:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moghanaki D, Karas T. Surgery versus SABR for NSCLC. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e490–e491. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louie AV, Senthi S, Palma DA. Surgery versus SABR for NSCLC. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e491. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah A, Hahn SM, Stetson RL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of stereotactic body radiation therapy versus surgical resection for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:3123–3132. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senan S. Surgery versus stereotactic radiotherapy for patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: More data from observational studies and growing clinical equipoise. Cancer. 2013;119:2668–2670. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirvani SM, Jiang J, Chang JY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of 5 treatment strategies for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:1060–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.07.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louie AV, Rodrigues G, Hannouf M, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy versus surgery for medically operable Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: A Markov model-based decision analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:964–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senthi S, Senan S. Surgery for early-stage lung cancer: Post-operative 30-day versus 90-day mortality and patient-centred care. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:675–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundaresan S, McLeod R, Irish J, et al. Early results after regionalization of thoracic surgical practice in a single-payer system. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:472–478; discussion 478–479. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palma D, Lagerwaard F, Rodrigues G, et al. Curative treatment of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer in patients with severe COPD: Stereotactic radiotherapy outcomes and systematic review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1149–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeil BJ, Weichselbaum R, Pauker SG. Fallacy of the five-year survival in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:1397–1401. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197812212992506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palma DA, Senan S. Early-stage non-small cell lung cancer in elderly patients: Should stereotactic radiation therapy be the standard of care? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:1058–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.07.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitera G, Swaminath A, Rudoler D, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing conventional versus stereotactic body radiotherapy for surgically ineligible stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e130–e.136. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senthi S, Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, et al. Outcomes of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for central lung tumours: A systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2013;106:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sher DJ, Wee JO, Punglia RS. Cost-effectiveness analysis of stereotactic body radiotherapy and radiofrequency ablation for medically inoperable, early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:e767–e774. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grutters JP, Kessels AG, Pijls-Johannesma M, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of radiotherapy with photons, protons and carbon-ions for non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2010;95:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wood DE, Eapen GA, Ettinger DS, et al. Lung cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:240–265. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: A systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307:2418–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:910–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seigneurin A, Field JK, Gachet A, et al. A systematic review of the characteristics associated with recall rates, detection rates and positive predictive values of computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:781–789. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senan S, Paul MA, Lagerwaard FJ. Treatment of early-stage lung cancer detected by screening: Surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy? Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e270–e274. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70592-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lund CR, Cao JQ, Liu M, et al. The distribution and patterns of practice of stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy in Canada. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2014;45:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]