The purpose of this study was to evaluate how BRCA genetic test result disclosure and patient characteristics influence attitudes about preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), prenatal diagnosis (PND), and future childbearing. Intentions to undergo PND or PGD do not appear to change after disclosure of BRCA results. Additional counseling for patients who have undergone BRCA testing may be warranted to educate patients about available fertility preservation options.

Keywords: Breast cancer, BRCA, Genetics, Fertility, Preimplantation genetic diagnosis

Abstract

Background.

Women with premenopausal breast cancer may face treatment-related infertility and have a higher likelihood of a BRCA mutation, which may affect their attitudes toward future childbearing.

Methods.

Premenopausal women were invited to participate in a questionnaire study administered before and after BRCA genetic testing. We used the Impact of Event Scale (IES) to evaluate the pre- and post-testing impact of cancer or carrying a BRCA mutation on attitudes toward future childbearing. The likelihood of pursuing prenatal diagnosis (PND) or preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) was also assessed in this setting. Univariate analyses determined factors contributing to attitudes toward future childbearing and likelihood of PND or PGD.

Results.

One hundred forty-eight pretesting and 114 post-testing questionnaires were completed. Women with a personal history of breast cancer had less change in IES than those with no history of breast cancer (p = .003). The 18 BRCA-positive women had a greater change in IES than the BRCA-negative women (p = .005). After testing, 31% and 24% of women would use PND and PGD, respectively. BRCA results did not significantly affect attitudes toward PND/PGD.

Conclusion.

BRCA results and history of breast cancer affect the psychological impact on future childbearing. Intentions to undergo PND or PGD do not appear to change after disclosure of BRCA results. Additional counseling for patients who have undergone BRCA testing may be warranted to educate patients about available fertility preservation options.

Abstract

摘要

背景。患有绝经前乳腺癌的女性可能面临患上与治疗相关之不孕症的风险,且出现 BRCA 突变的可能性更高,这可能影响她们对未来生育孩子的态度。

方法。绝经前女性受邀参与一项问卷调查研究,该研究在 BRCA 基因检测之前和之后分别施行。我们使用了事件影响量表 (IES) ,在检测前和检测后对癌症或携带 BRCA 突变会对未来生育孩子之态度产生何种影响作了评估。在此设置环境下,也对寻求产前诊断 (PND) 或植入前遗传学诊断 (PGD) 的可能性作了评估。单因素分析确定了有助于促成未来愿意生育孩子以及愿意寻求 PND 或 PGD 的因素。

结果。完成了 148 份检测前和 114 份检测后调查问卷。有乳腺癌个人病史的女性的 IES 变化小于没有乳腺癌史的女性 (p = 0.003)。18 名 BRCA 为阳性之女性的 IES 变化大于 BRCA 为阴性的女性 (p = 0.005)。检测之后,分别有 31% 和 24% 的女性会使用 PND 和 PGD。BRCA 结果并未显著影响对使用 PND/PGD 的态度。

结论。BRCA 结果和乳腺癌史会对未来生育孩子的态度产生心理影响。接受 PND 或 PGD 的意向在披露 BRCA 结果后似乎没有改变。可能需要对接受 BRCA 检测的患者提供额外咨询,以让患者了解可用于保护生育能力的方案选项。 (The Oncologist) 2014;19:797–804

Implications for Practice:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate how BRCA genetic test result disclosure and patient characteristics influence attitudes about preimplantation genetic diagnosis and future childbearing. Such an understanding could significantly improve the ability of genetic counselors and healthcare providers to counsel women with possible or identified BRCA mutations. Capturing the opinions on this topic, both before genetic counseling and after result disclosure, can help determine effects on decisions towards future reproduction. These results help health care professionals provide the appropriate information and support during BRCA pre- and postcounseling.

Introduction

Approximately 1 in 200 women under the age of 40 were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2012 [1]. Breast cancer treatment often includes cytotoxic and endocrine therapies that can impair ovarian function and may interrupt childbearing plans [2–4]. Postponing pregnancy after a breast cancer diagnosis may also reduce fertility as a result of advancing maternal age [5]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends that potential treatment-related infertility be discussed at the earliest opportunity so patients can understand and pursue appropriate fertility preservation options [6]. However, many young women who have undergone cancer treatment often do not recall any discussions regarding the impact of cancer treatment on reproductive function or were dissatisfied with the amount of information provided [7–10].

Women diagnosed with premenopausal breast cancer also have a higher risk of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC), which is associated with mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes [11]. After diagnosis of a BRCA mutation, women with HBOC may be less likely to desire additional children than noncarriers [12]. Women with unfulfilled childbearing plans are significantly more distressed about treatment-related infertility, even 10 years after diagnosis [13, 14]. This concern may be compounded when discussing BRCA genetic testing and the implications of a positive result for future and current children [15, 16].

With assisted reproductive technologies (ART), alternative childbearing options are available. Beyond the choices of adoption and oocyte donation, women who desire to have their own biological children yet avoid transmission of a BRCA mutation may be offered prenatal diagnosis (PND), including chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis. These methods are invasive and confer a slightly increased risk of miscarriage. In addition, they may present complicated and difficult choices regarding termination or continuation of an affected pregnancy [17]. A possible alternative to PND is preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). PGD is performed on embryos created through the process of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Embryos are genetically tested for a hereditary condition, such as a BRCA mutation, carried by either parent. Only the unaffected embryos are used to try to conceive.

Patients and providers must recognize some barriers to PGD, particularly for women diagnosed with cancer. The high cost of IVF and PGD is often a burden, particularly when combined with the cost of cancer treatment [18]. Recently, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine stated that oocyte cryopreservation is no longer an experimental procedure [19]. With improvements in oocyte cryopreservation techniques, women may have the additional option to create embryos with their oocytes closer to desired conception. PGD could be considered and accomplished at that time [20, 21]. Studies examining the opinions toward PGD among men and women with a BRCA mutation have shown that 13%–33% would want to pursue PGD if they were trying to conceive [22–25].

Because fertility preservation must be discussed as early as possible after a breast cancer diagnosis, women with a BRCA mutation face the additional burden of making future-oriented reproductive decisions in a short time frame while under significant stress [26]. With the increasing availability and effectiveness of ART, it is important to understand patients’ attitudes toward childbearing in the context of cancer and BRCA mutations [19]. Such an understanding could significantly improve the ability of genetic counselors and fertility specialists to counsel women with possible or identified BRCA mutations. Although opinions of women with a BRCA mutation regarding PGD have been reported, to our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively evaluate the impact of genetic test results on these attitudes. The purpose of this study was to evaluate how BRCA genetic test result disclosure and patient characteristics influence attitudes about PND, PGD, and future childbearing.

Materials and Methods

Women of childbearing age referred to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Clinical Cancer Genetics Program from 2009 to 2011 for HBOC evaluation and genetic consultation were invited to participate in this institutional review board-approved study. Participants completed a questionnaire prior to genetic counseling, and those who underwent genetic testing completed the same questionnaire again following receiving their test results either at their genetic counseling follow-up appointment or by mail.

The psychological impact of cancer and/or carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and the implications for future childbearing were measured using the Impact of Event Scale (IES) [27]. Participants indicated their level of distress for each item on the IES on the basis of their response to the following event: “During the past 7 days I have thought about the impact of cancer or of being a genetic carrier of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene on my ability to conceive or carry a pregnancy successfully.” Three composite scores were calculated from responses to the 15 standard IES items, including intrusion and avoidance subscales and a total score. Responses were scored as 0 for a negative endorsement (“Not at all”) and as 1, 3, or 5 for the three degrees of positive endorsement (“Rarely,” “Sometimes,” and “Often”). Primary outcome measures were the total change in IES (tcIES), intrusion change in IES (icIES), and avoidance change in IES (acIES) scores from before counseling to after receiving results. A positive change in IES corresponds to an increase in distress based on the life event. Univariate analyses were performed to test the significance of the associations between patient characteristics and tcIES, icIES, and acIES using analysis of variance or Spearman correlation coefficients [28]. A linear regression model was obtained by first including an initial set of candidate predictor variables with p ≤ .05 in the univariate analysis and then used to evaluate the associations between patient characteristics and the changes in IES in a multifactor setting [28].

Participants were also questioned about their attitudes toward pregnancy and fertility, as well as the likelihood of pursuing PND or PGD [9]. A short explanation of PND and PGD was provided within the questionnaire. Women provided their attitudes toward PND and PGD under the assumption that they carried an inherited gene mutation by answering the following questions: “How likely would you be to use in vitro fertilization with genetic testing of the embryos?,” “How likely would you be to have the fetus tested during a future pregnancy (through chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis) for an inherited gene mutation?,” and “Do you think that society should allow in vitro fertilization and use of pre-implantation embryo testing to be available to families with inherited cancer problems?” The first two questions had five possible responses ranging from “definitely not” to “definitely.” The third question had two possible responses: yes or no. In the analyses, to avoid adverse effects of sparse data on parameter estimation, we combined the negative endorsements (“definitely not” and “probably not”) into the category “negative,” the positive endorsements (“definitely” and “probably”) into “positive,” and kept “undecided” as “undecided.”

Univariate analyses were performed to test the associations between patient characteristics of interest and attitudes about pregnancy and fertility using a multinomial regression model [29]. A multivariate multinomial regression model was obtained by first including an initial set of candidate predictor variables with a p value of <.10 in the univariate analysis. Backward elimination model selection using a significance level of .05 was performed to select variables for linear regression or multinomial regression model. Once these variables were selected, the functional form of each variable and multicollinearity between the variables were examined. Income and marital status were strongly correlated with each other and therefore were not included in the same multinomial regression models in the model selection procedure.

Some participants did not complete all questions on a given questionnaire. Analyses were performed on available data noted by the denominator indicating number of completed questions. All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, http://www.sas.com), and S-PLUS (version 8.04; S-Plus, Palo Alto, CA, http://s-plus-8.0.softinfodb.com) was used to carry out the computations for all analyses.

Results

One hundred fifty-five women completed precounseling questionnaires. Seven of them were excluded from analysis owing to reported loss of childbearing potential prior to cancer treatment. Of the remaining 148 women, 30 did not undergo genetic testing, and 4 were lost to follow-up. Hence, we analyzed 114 postcounseling questionnaires. Study population characteristics are shown in Table 1. Women who completed precounseling questionnaires had a mean age of 35 years and a median of 36 years (SD = 6 years, range = 20–45 years). Seventy percent (104 of 148) of women who completed precounseling questionnaires were diagnosed with breast cancer, and 60% (62 of 103) of affected women had already received chemotherapy, excluding one individual that did not have chemotherapy information available. Thirty-two women stated that they were not currently having menstrual cycles, possibly owing to their birth control use or to concomitant chemotherapy; however, all women had been premenopausal prior to starting chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics

Of the women who completed the precounseling questionnaire, 57% (46 of 81) of the women less than or equal to 36 years old and 28% (17 of 60) of the women over 36 years old expressed interest in future childbearing (seven individuals did not report an age). After receiving genetic test results, 55% (35 of 64) of the younger women and 19% (8 of 43) of the older women still expressed interest in future childbearing. Of the women who underwent genetic testing, 13 tested positive for a BRCA1 mutation and 5 tested positive for a BRCA2 mutation. Six women carried a variant of uncertain significance in either BRCA1 or BRCA2. Women with a variant of uncertain significance in either BRCA gene were excluded from all final analyses, given the ambiguous nature of this genetic test result.

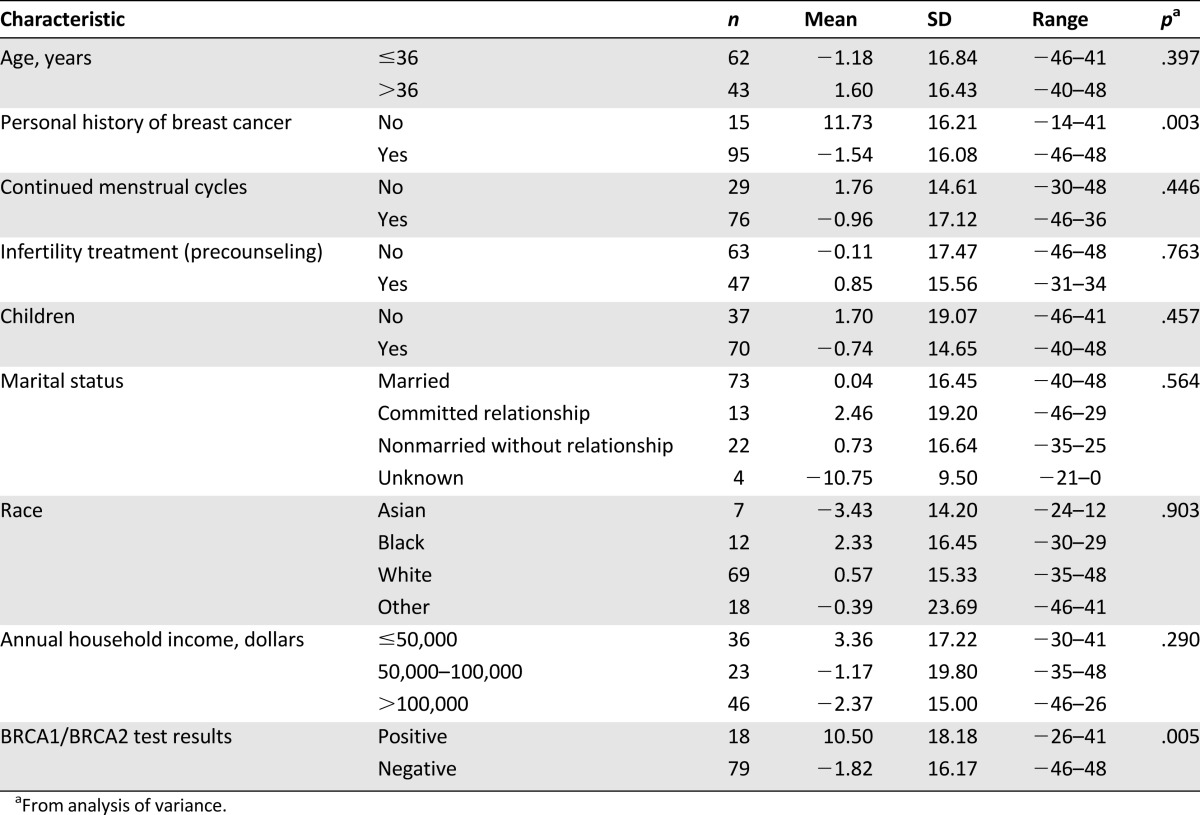

Associations between the results of the tcIES and patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis indicated age was negatively correlated with IES scores on the precounseling questionnaire (Spearman correlation coefficient [r] = −.20, p = .017) and on the postresults questionnaire (r = −.18, p = .072). Younger women reported higher IES scores (i.e., more experience of distress specific to future pregnancies and cancer and/or BRCA mutation status) than older women. However, age was not significantly correlated with the tcIES between the two questionnaires (r = .03, p = .725).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and total change in Impact of Event Scale

Participants with a personal history of breast cancer had significantly lower mean tcIES scores than those who had not been diagnosed with breast cancer (p = .003). The average tcIES score of patients without breast cancer increased by 11.73 (SD = 16.21) after counseling compared with before counseling, whereas the average tcIES score among individuals with a history of breast cancer decreased by −1.54 (SD = 16.08). Participants who were BRCA-positive had higher tcIES than those who were BRCA-negative (p = .005). The average tcIES of the BRCA-positive patients was 10.50 (SD = 18.18) higher after BRCA result disclosure compared with before counseling, whereas the average tcIES among BRCA-negative individuals was −1.82 (SD = 16.17). No other patient characteristics were shown to be significantly associated with tcIES in the univariate analyses. In multivariate analyses, participants who were BRCA-positive had higher tcIES than those who were BRCA-negative (p = .029) with adjustment of a diagnosis of breast cancer (p = .039).

In univariate analyses of the IES subscales (avoidance and intrusion), BRCA results, and a personal history of cancer were the only variables that significantly changed between pre- and postquestionnaire. Multivariate analyses showed that women without breast cancer had a significant increase on icIES after receiving genetic test results (p = .008) but not on acIES (p = .081). In regards to BRCA genetic test results, BRCA-positive individuals had significantly higher acIES (p = .021), but not a significant change on icIES (p = .084) compared with BRCA-negative individuals.

Analysis of women’s attitudes toward genetic testing of future pregnancies was based on the intended use of PND and PGD. Of the women who completed the precounseling questionnaire, 26% (38 of 144) and 28% (40 of 142) expressed a high likelihood of using PND and PGD, respectively, if they knew or suspected their cancer was caused by an inherited gene mutation. After receiving their BRCA genetic test results, 31% (35 of 112) were likely to pursue PND, and 24% (27 of 113) would use PGD. Prior to counseling, there was no significant difference between the decisions to pursue PND versus PGD (p = .468) nor following result disclosure (p = .475).

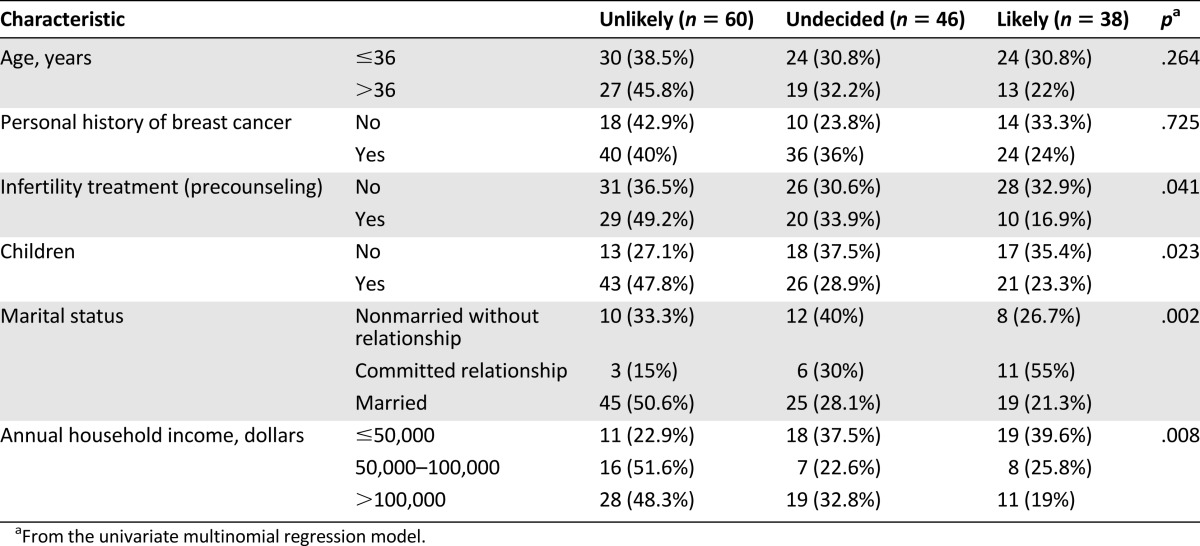

Attitudes toward PND on the precounseling questionnaire are shown in Table 3. Several characteristics demonstrated statistical significance and were further evaluated by multinomial regression models. Specifically, women without children were more likely to have PND for BRCA mutations than those with children (p = .014). Patients whose annual household income was <$50,000 were more likely to use PND than those with an income of $50,000–$100,000 (p = .059) or >$100,000 (p = .005). Regarding marital status, patients who were not married but in a committed relationship were more likely to use PND than married individuals (p = .001) and those not in a committed relationship (p = .063). None of the patient characteristics were significantly associated with a difference in attitude toward PND on the postresults questionnaire. Specifically, BRCA test results did not significantly differ attitudes regarding PND between BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative patients (p = .247).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics and precounseling intentions of prenatal diagnosis in the univariate setting

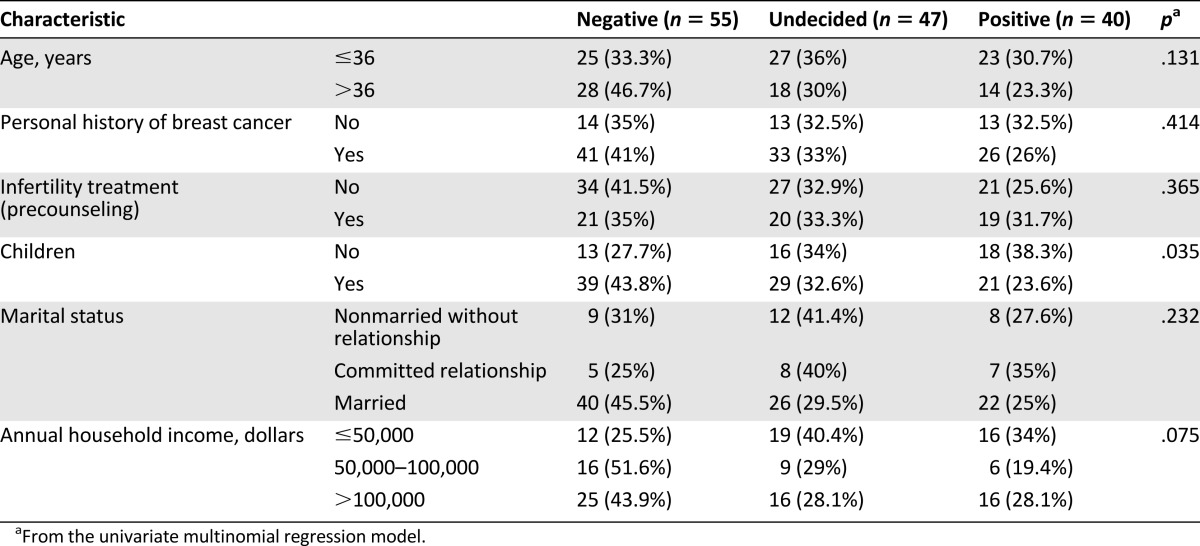

Table 4 shows precounseling likelihood to pursue PGD. Participants who did not have children were more likely to use PGD than those with children (p = .035). The same pattern was observed on the postresults questionnaire (p = .001). There was no significant difference between the likelihood of participants who tested BRCA-positive or -negative toward intentions to use PGD (p = .206).

Table 4.

Patient characteristics and precounseling intentions of preimplantation genetic diagnosis in the univariate setting

Lastly, the distribution of patients who held positive, undecided, or negative attitudes toward PND and PGD was the same before counseling and after testing (p = .845 for PND and p = .497 for PGD). Although a substantial number of women said they were unlikely to pursue PGD, prior to counseling, 83% (114 of 138) of the women said that PGD should be available to families with inherited cancer syndromes. Following result disclosure, 79% (87 of 110) still believed PGD should be available for this purpose.

Discussion

We found that undergoing BRCA genetic testing is a distressing event in a young woman’s life that can significantly impact her feelings about future family building. Although a notable proportion of our study population would not pursue PND or PGD, a substantial percentage were undecided, which warrants further investigation into the factors impacting the decision to use PND and/or PGD. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to assess the immediate effects of BRCA result disclosure and history of breast cancer on future childbearing plans and the likelihood of pursuing PND or PGD.

Personal history of breast cancer and BRCA test results significantly affected the postresults change in participants’ distress regarding childbearing plans. Women without a history of breast cancer were more likely to increase in distress on the IES than those with a history of breast cancer. Women with a personal history of breast cancer have already been impacted by a major life event. This experience has been reported among a population of BRCA1 carriers noting higher distress levels among those with no history of cancer, suggesting that women with cancer may perceive a higher likelihood of a positive test result given their personal history, attenuating the impact of distress [30]. A more recent study reported BRCA-positive result disclosures were more distressing on individuals with cancer compared with those unaffected; however, the sample size of affected individuals was small [31]. Further investigation is warranted to determine how these populations differ in their response to positive results, particularly in the context of childbearing. When evaluating the subscales of the IES, women without a history of breast cancer showed a significant increase in IES after result disclosure in the intrusion response set (p = .008) but not on the avoidance response set. Women without a history of breast cancer experienced more intrusive thoughts (i.e., other things kept making them think about it or they thought about it when they did not mean to) regarding a future pregnancy.

Participants in our study showed a significant change in IES responses after receiving BRCA test results. Women with a positive test result reported more distress with regard to future childbearing than that reported prior to genetic testing; this increase in distress was significant in the avoidance subscale but not in the intrusion subscale (p = .021 and p = .084, respectively) compared with noncarriers. Among young female cancer survivors desiring a future pregnancy, avoidance is used as a coping strategy when reminded of concerns regarding infertility [13]. Previous studies have found similar reactions from patients undergoing HBOC genetic counseling; after result disclosure, BRCA carriers exhibited increased levels of distress immediately following the disclosure of test results, but this distress dissipated over time [32].

Receiving a diagnosis of breast cancer or having a BRCA mutation is an anxiety-provoking event that can impact patients’ psychosocial well-being [30, 33–36]. Using the IES, we found that younger women (≤36 years) reported more distress about a future pregnancy than older participants (>36 years) (p = .017). However, age was not significantly correlated with a change in this impact between the precounseling and postresult questionnaires. Although all women in this study were assumed to have childbearing potential, it is understandable that the younger group of women would be more strongly impacted, because these events were more likely to occur at a time that interrupts childbearing. Previous studies noted that a positive BRCA test result reduced the likelihood to have additional children [12, 37]. Our study showed a decreased interest in future childbearing, specifically among women of >36 years of age, after BRCA genetic test result disclosure. Whether the experience of cancer in this population and undergoing genetic testing in combination affect this trend or work independently is not known. Schover et al. [9] found that 56% of young male and female cancer survivors still expressed a substantial interest in future childbearing. The diagnosis of cancer did not alter previous desires in the majority of participants, particularly among individuals with no previous children. In contrast, Smith et al. [12] found that women who were BRCA1 mutation carriers were less likely to want additional children compared with noncarriers. The impact of BRCA results over time was investigated in a large retrospective study of male and female BRCA carriers without a personal history of breast cancer at least 1 year after their genetic test result disclosure. Eighty-four percent (385 of 460) of the study population stated that the BRCA result disclosure did not affect their ongoing reproductive plans [25]. These differences in intentions are captured along varying timelines and potentially different age groups after the adverse event and may suggest a change in childbearing plans over time. The younger subset of our population did not particularly change their interests in future childbearing, consistent with previous studies; however, our older subset showed decreased interest, reflecting the differences between these age groups.

Our study also captured the likelihood to use PND and/or PGD in a young, high-risk population because these procedures may offer BRCA-positive individuals options in future family planning. We found 26% and 28% of women, prior to BRCA testing, would likely use PND and PGD, respectively. Following BRCA result disclosure, 31% would likely use PND and 24% would use PGD. There was no statistical difference between the likelihood to use PND versus PGD. PGD has been reported as a more acceptable option than PND because of the difficult decisions surrounding termination of pregnancies testing positive for a hereditary condition, particularly in regards to adult-onset conditions [38, 39]. The similar likelihood to pursue PND or PGD suggests patients may not fully comprehend the differences between these methods.

Previous studies have evaluated opinions toward PGD in a retrospective setting. The present study aimed to capture the immediate impact of BRCA genetic test results and the theoretical likelihood of pursuing these procedures, because thoughts and feelings toward the topic may change over time. Staton et al. [22] found that 88% of the BRCA-positive women participating in their study were worried about the potential transmission of the known mutation to their children, but only 13% would consider PGD. Menon et al. [23] reported that 38% of BRCA-positive participants who had completed childbearing plans would have considered PGD, but only 14% of the BRCA-positive individuals still planning a future pregnancy would consider PGD. The theoretical use of PGD among BRCA carriers has consistently been a smaller percentage of the high-risk population, and often, those reporting a higher likelihood of pursuing PGD are those not planning a future pregnancy, which is consistent with the findings seen in the present study [24, 25]. Interestingly, BRCA test results did not affect the likelihood of pursuing PGD. This finding may indicate that the theoretical likelihood of using PGD is more dependent on an a priori opinion toward the method than on testing outcomes. Several ethical and social considerations influence an individual’s attitudes toward the use of PGD, including opinions about the use of IVF, selection of embryos based on genetic characteristics (particularly for an adult-onset condition), perceived burden of the condition, and personal experience [25, 40–42].

Regardless of the likelihood to pursue PGD, 79% of women we surveyed after result disclosure stated that PGD should be available to families with inherited cancer syndromes. It has previously been reported that women believe that information about PGD should be provided to mutation carriers, primarily from their genetic counselor [24]. With such a large percentage of BRCA mutation carriers noting the importance of receiving information regarding PGD, the question of when to provide education on PGD during the course of HBOC diagnosis and counseling needs to be answered. Julian-Reynier et al. [25] reported that the majority of BRCA carriers expected information regarding PGD/PND along with genetic test results by a cancer geneticist, whereas Hurley et al. [43] noted that BRCA carriers were often overwhelmed at the time of the genetic result disclosure and that careful psychosocial assessment should determine the best timing for information delivery. This supports the utility of a multidisciplinary team, including providers from oncology, genetic counseling, psychiatry, and reproductive medicine in the development of personalized assessment.

One limitation of this study is the potential variation in the time between the two questionnaires. Although surveys were provided at the genetic counseling result disclosure when possible, if results were provided by telephone, then timing to completion of the mailed survey could not be controlled. This lack of control limits the ability to account for confounding effects of cancer treatment and other variables that may have affected the completion of the survey. Also, the total number of patients analyzed and the number of BRCA-positive patients were small, allowing the observation of trends but only a few statistically significant results. Although a short description of PND and PGD was provided, individuals may have lacked a complete understanding of these methods including the benefits and risks. Additionally, the barriers to accessibility of these procedures, including financial or physical, were not assessed.

Another unknown variable of this analysis is whether the region where people live affect both their attitude and/or uptake of PGD or PND. This analysis included patients both local to our institution as well as those who traveled from other states to this tertiary care facility. However, this analysis is limited by small numbers of patients from most other regions other than Texas. Future analyses and collaborations would be helpful in determining whether geographical region affects these findings.

Conclusion

This study was unique in its ability to capture opinions both before and after BRCA result disclosure. Women without a history of breast cancer who were found to be BRCA carriers experienced more distress after genetic test disclosure. Women with breast cancer who had an identified BRCA mutation did not show a significant change between their precounseling and postresults responses, which suggests that the impact of a breast cancer diagnosis supersedes the impact of having a BRCA gene mutation. Most of the women surveyed believed that PGD should be discussed and offered as a reproductive option; however, few would pursue PGD in a theoretical future pregnancy. Premenopausal women may benefit from further discussion beyond a one-time genetic result disclosure session. Additional counseling sessions provide an opportunity for improved processing time and repetitive counseling on the important topics and decisions, particularly time to explore the available options, such as cryopreservation and deferring decisions regarding PGD.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support provided by the Wolff-Toomim Fund and the Texas Business Women Fund. We thank Sarah Bronson in the Department of Scientific Publications at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for grammatical assistance and stylistic suggestions for this publication.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: For further reading on the topic of infertility in young breast cancer survivors, see “Estimates of Young Breast Cancer Survivors at Risk for Infertility in the U.S.” by Katrina F. Trivers et al., on pages 814–822 of this issue.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Leslie Schover, Jennifer K. Litton

Provision of study materials or patients: Ashley H. Woodson, Kimberly I. Muse, Michelle Jackson, Richard L. Theriault, Gabriel N. Hortobágyi, Banu Arun, Jennifer K. Litton

Collection and/or assembly of data: Ashley H. Woodson, Danielle N. Mattair, Jennifer K. Litton

Data analysis and interpretation: Ashley H. Woodson, Heather Lin, Jennifer K. Litton

Manuscript writing: Ashley H. Woodson, Kimberly I. Muse, Heather Lin, Jennifer K. Litton

Final approval of manuscript: Ashley H. Woodson, Kimberly I. Muse, Heather Lin, Michelle Jackson, Danielle N. Mattair, Leslie Schover, Terri Woodard, Laurie McKenzie, Richard L. Theriault, Gabriel N. Hortobágyi, Banu Arun, Susan K. Peterson, Jessica Profato, Jennifer K. Litton

Disclosures

Richard L. Theriault: UpToDate (Other); Gabriel N. Hortobágyi: Antigen Express, Novartis, Pfizer, Taivex (C/A); Novartis (RF); Jennifer K. Litton: Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Biomarin (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bath LE, Wallace WH, Shaw MP, et al. Depletion of ovarian reserve in young women after treatment for cancer in childhood: Detection by anti-Müllerian hormone, inhibin B and ovarian ultrasound. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2368–2374. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne J, Fears TR, Gail MH, et al. Early menopause in long-term survivors of cancer during adolescence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:788–793. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, et al. Risk of menopause during the first year after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2365–2370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasch J, Gratacós E. Delayed childbearing: Effects on fertility and the outcome of pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24:187–193. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283517908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2917–2931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thewes B, Meiser B, Rickard J, et al. The fertility- and menopause-related information needs of younger women with a diagnosis of breast cancer: A qualitative study. Psychooncology. 2003;12:500–511. doi: 10.1002/pon.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge AH, Gelber S, Peppercorn J, et al. Web-based survey of fertility issues in young women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4174–4183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schover LR, Rybicki LA, Martin BA, et al. Having children after cancer. A pilot survey of survivors’ attitudes and experiences. Cancer. 1999;86:697–709. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<697::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffy CM, Allen SM, Clark MA. Discussions regarding reproductive health for young women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:766–773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith KR, Ellington L, Chan AY, et al. Fertility intentions following testing for a BRCA1 gene mutation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:733–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canada AL, Schover LR. The psychosocial impact of interrupted childbearing in long-term female cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2012;21:134–143. doi: 10.1002/pon.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camp-Sorrell D. Cancer and its treatment effect on young breast cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speice J, McDaniel SH, Rowley PT, et al. Family issues in a psychoeducation group for women with a BRCA mutation. Clin Genet. 2002;62:121–127. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch HT, Snyder C, Lynch JF, et al. Patient responses to the disclosure of BRCA mutation tests in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer families. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;165:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milunsky A, Milunsky JM. Genetic disorders and the fetus: Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fasouliotis SJ, Schenker JG. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis principles and ethics. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2238–2245. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.8.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Practice Committees of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Mature oocyte cryopreservation: A guideline. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Toukhy T, Kamal A, Wharf E, et al. Reduction of the multiple pregnancy rate in a preimplantation genetic diagnosis programme after introduction of single blastocyst transfer and cryopreservation of blastocysts biopsied on day 3. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2642–2648. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Landuyt L, Verpoest W, Verheyen G, et al. Closed blastocyst vitrification of biopsied embryos: Evaluation of 100 consecutive warming cycles. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:316–322. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staton AD, Kurian AW, Cobb K, et al. Cancer risk reduction and reproductive concerns in female BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Fam Cancer. 2008;7:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s10689-007-9171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menon U, Harper J, Sharma A, et al. Views of BRCA gene mutation carriers on preimplantation genetic diagnosis as a reproductive option for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1573–1577. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, Wilson C, et al. Attitudes of high-risk women toward preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2361–2368. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Julian-Reynier C, Fabre R, Coupier I, et al. BRCA1/2 carriers: Their childbearing plans and theoretical intentions about having preimplantation genetic diagnosis and prenatal diagnosis. Genet Med. 2012;14:527–534. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Oktay K. Fertility preservation and pregnancy in women with and without BRCA mutation-positive breast cancer. The Oncologist. 2012;17:1409–1417. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woolson R, Clarke W. Statistical Methods for the Analysis of Biomedical Data. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croyle RT, Smith KR, Botkin JR, et al. Psychological responses to BRCA1 mutation testing: Preliminary findings. Health Psychol. 1997;16:63–72. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Roosmalen MS, Stalmeier PF, Verhoef LC, et al. Impact of BRCA1/2 testing and disclosure of a positive test result on women affected and unaffected with breast or ovarian cancer. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;124A:346–355. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton JG, Lobel M, Moyer A. Emotional distress following genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2009;28:510–518. doi: 10.1037/a0014778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Oostrom I, Meijers-Heijboer H, Lodder LN, et al. Long-term psychological impact of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation and prophylactic surgery: A 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3867–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beran TM, Stanton AL, Kwan L, et al. The trajectory of psychological impact in BRCA1/2 genetic testing: Does time heal? Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:107–116. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, et al. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: Five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C, et al. Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early-stage patients. Health Psychol. 1999;18:159–168. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fortuny D, Balmaña J, Graña B, et al. Opinion about reproductive decision making among individuals undergoing BRCA1/2 genetic testing in a multicentre Spanish cohort. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1000–1006. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ormondroyd E, Donnelly L, Moynihan C, et al. Attitudes to reproductive genetic testing in women who had a positive BRCA test before having children: A qualitative analysis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:4–10. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cameron C, Williamson R. Is there an ethical difference between preimplantation genetic diagnosis and abortion? J Med Ethics. 2003;29:90–92. doi: 10.1136/jme.29.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knoppers BM, Bordet S, Isasi RM. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis: An overview of socio-ethical and legal considerations. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:201–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vergeer MM, van Balen F, Ketting E. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis as an alternative to amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: Psychosocial and ethical aspects. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;35:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang CW, Hui EC. Ethical, legal and social implications of prenatal and preimplantation genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19(Suppl 2):23–33. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hurley K, Rubin LR, Werner-Lin A, et al. Incorporating information regarding preimplantation genetic diagnosis into discussions concerning testing and risk management for BRCA1/2 mutations: A qualitative study of patient preferences. Cancer. 2012;118:6270–6277. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]