Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of quality of care (QoC) on patients’ quality of life (QoL). In a cross-sectional study, two domains of QoC and the World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref questionnaire were combined to collect data from 1,059 pre-discharge patients in four accredited hospitals (ACCHs) and four non-accredited hospitals (NACCHs) in Saudi Arabia. Health and well-being are often restricted to the characterization of sensory qualities in certain settings such as unrestricted access to healthcare, effective treatment, and social welfare. The patients admitted to tertiary health care facilities are generally able to present themselves with a holistic approach as to how they experience the impact of health policy. The statistical results indicated that patients reported a very limited correlation between QoC and QoL in both settings. The model established a positive, but ultimately weak and insignificant, association between QoC (access and effective treatment) and QoL (r = 0.349, P = 0.000; r = 0.161, P = 0.000, respectively). Even though the two settings are theoretically different in terms of being able to conceptualize, adopt, and implement QoC, the outcomes from both settings demonstrated insignificant relationships with QoL as the results were quite similar. Though modern medicine has substantially improved QoL around the world, this paper proposes that health accreditation has a very limited impact on improving QoL. This paper raises awareness of this topic with multiple healthcare professionals who are interested in correlating QoC and QoL. Hopefully, it will stimulate further research from other professional groups that have new and different perspectives. Addressing a transitional health care system that is in the process of endorsing accreditation, investigating the experience of tertiary cases, and analyzing deviated data may limit the generalization of this study. Global interest in applying public health policy underlines the impact of such process on patients’ outcomes. As QoC accreditation does not automatically produce improved QoL outcomes, the proposed study encourages further investigation of the value of health accreditation on personal and social well-being.

Keywords: accreditation, quality of care, quality of life, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

The common hypothesis among healthcare professionals is that high mortality and morbidity rates in many low-income countries can be attributed to ineffective health policies.1–3 A lack of basic life needs such as clean water, sanitation,4 and unproductive healthcare systems5 are significant social health inequalities at the macro-level. Although alleviating pain and its consequences is one of the major goals of medicine,6 the current trend of healthcare regulations in many health systems focuses on hospitals,7 and not on patients nor their needs and expectations. Health regulations, which once served the community, now serve the health institutions. Patients’ well-being is affected by multiple factors including accreditation policy and quality of care (QoC) implementation. With respect to hospitalization, these concepts may reveal substantial effects on social welfare. The unintended consequence of improving quality of life (QoL) is often hindered by our dominant logic about the effectiveness of some health policies. The simple question that is raised here is: what is the impact of substantive regulations, especially high QoC, on patients’ health and well-being? The objective of this study is, therefore, to explore the impact of QoC on patients’ QoL in a Saudi sample. The study addresses healthcare access and treatment effectiveness as major dimensions of QoC in accredited and non-accredited public hospitals, and how that may influence patients’ QoL in tertiary health settings.

Health care accreditation

Perhaps the most prevailing and implemented health policy worldwide in the last three decades is health accreditation. The prevalence of hospital accreditation has increased as hospital quality standards have improved.8 To pass accreditation, a healthcare organization must undergo an external assessment by an independent body. The assessment represents a measure of the level of compliance to prescribed standards of the healthcare service.9 Accreditation status demonstrates that a healthcare organization has already achieved minimum safety and quality standards.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Council addressed the definition of quality and stated: “quality of care is the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”10 Generally, the aim of quality in healthcare is continuous patient improvement.11 The rationale behind adopting healthcare standards is based on both patient safety and better health outcomes. For instance, high levels of preventable injuries among inpatients can be easily addressed through compliance of inpatient healthcare standards. Many health researchers and organizations claim that the aim of healthcare quality is to attain optimal health outcomes.12,13 Health accreditation is a functional landmark of hospital performance in almost all healthcare systems.14

Saudi Arabia healthcare system

The Saudi Arabia (SA) healthcare system has recently adopted a policy of continuous improvement with a focus on better health outcomes for patients, improvement in QoL, and meeting patients’ expectations and values including personal well-being and social welfare.15 These social welfare issues address nonmedical and socioeconomic concerns, such as difficulty in acquiring transport to a medical facility, which may prevent patients from being able to access the healthcare available to them.

In a bureaucratic and centralized system, the Ministry of Health (MOH); as a single body finances, controls, and regulates the SA healthcare system.16 Furthermore, the Saudi HealthCare Council’s recent endorsement of innovations, such as the accreditation program, demonstrates their determination to implement QoC in all MOH facilities.

The government, as the principal provider of healthcare, introduced the Central Board of Accreditation for Healthcare Institutions (CBAHI), thereby ensuring all national hospitals now have effective clinical management, in addition to qualified staff, to improve the quality of healthcare delivery. The accreditation of 21 public hospitals has prompted many other hospitals and health professionals to consider the value of hospital accreditation on QoL.

Since its inception in 2005, CBAHI management has vowed to provide patients with “a high standard of health and medical care, supported by highly trained staff.”17 All hospitals are inspected by the MOH to ensure compliance with the national minimum standards and local regulations. The Riyadh Health Directorate (RHD) undertakes frequent and random assessments to ensure quality improvement processes are in place, and that patient care and treatment are continuously updated, improved, and visible.

Containing more than 881 standards, the CBAHI manual is based on comparable international standards18 with a culturally tailored orientation to reflect cultural sensitivities, conditions, and requirements. However, CBAHI has focused on 22 essential departmental standards aiming at “setting up a system where patient and staff safety and satisfaction are the focus of the operation.”17 Both public and private institutions are required to meet these standards, not only to improve their quality and patient safety, but also to be able to operate within the new health insurance schemes. All health standards are now measured against these performance indicators, whose primary focus is to improve and underpin current hospital performance. Although accreditation standards are comparable worldwide19 and are an essential part of the SA healthcare system, the IOM stresses its significance in contributing to optimizing organizational performance: “Accreditation is a useful tool for improving the quality for services provided to the public by setting standards and evaluating performance against those standards.”20

Using such standards in public health is widespread, as the aim is to “command and control health services.”21 Healthcare organizations implement a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) to judge how well they are performing. These KPIs are subjective and internally defined, and they are subject to reasonable criteria.22 O’Connor23 strongly believes that when selecting, developing, or modifying a test, one should take into account the main purpose behind the test. In designing a study to assess health standards, KPI selection should also consider the level of influence that a provider can hold.24 Therefore, KPIs are selected systematically, using criteria that are measurable, reliable, and take into account patient behavior. Once essential KPIs have been determined, how to measure them must then be decided.25,26 The ideal features of a quality indicator are: relevance to the study outcome; reliability of findings; ease of measurement; and amenability to quality control.27 A matrix of KPIs is necessary to avoid compromising overall performance by focusing on one KPI to the exclusion of others. This concept is known as “standardization” in healthcare services.

Hospital accreditation, however, does not always produce improved outcomes. For example, Sack et al28 found no significant relationships between accredited hospitals (ACCHs) and patient satisfaction. In fact, patients did not choose ACCHs because of their accreditation or because of the QoC they offered, but because of other factors such as patient satisfaction. Despite this, many healthcare policies and health services organizations continue to focus almost exclusively on attaining health accreditation in the belief that it is a major achievement for a health institution. The CBAHI, which introduced these standards, considers patient safety and expectation as the priority when delivering healthcare services.

Health accreditation has gained international and national attention. While highlighting the importance of implementing QoC, CBAHI cites patient expectations, better outcomes, and safety as their priorities for health services management and policymakers alike.17

QoC in tertiary care

To decipher whether the best practice of healthcare quality has been attained, the concepts of access and effectiveness are systematically addressed in any given health setting.29,30 Access covers the functionality of the intended healthcare services provided in meeting a patient’s needs, and how these services are made available. Effectiveness ensures that the healthcare provided involves the patient in its decision making and adopts certain institutional quality measures such as patient rights and safety. The primary purpose of QoC is to ensure that the quality of patient care is in accordance with contemporary established guidelines.31

Access to healthcare organizations

Having access to appropriate and timely use of personal health services may lead to the best health outcomes.32 Patients can face a nonclinical obstacle in accessing clinical services, such as admission procedures and bed availability. Conversely, they may face obstacles when accessing the clinics, for example a lack of a particular medical service could force them to seek out a different health facility. While the first situation emphasizes access functionality, the second pertains to health continuity under the right service availability. Both scenarios increase the likelihood of the irrational utilization of health services, and also place a greater financial burden on the patient and the hospital.33 Seamless referrals,34 periodical follow up, and the provision of best outcomes35 are all associated with how a hospital should function, and are referred to in this paper as “Tertiary Service Access” (TSA).

Nowadays, patients worldwide do not have adequate access to a national network of hospitals and clinics, nor can they obtain the local and basic medical treatment they might need. Sophisticated surgical procedures, such as open heart surgery and organ transplants, are routinely performed in most of the middle- and upper-economic countries by medical professionals who meet the highest international standards. In addition, medications are readily available to patients at a low cost since, in most cases, the government subsidizes such medical needs. The simple question that arises here is whether a hospital can offer actual tertiary healthcare services once a patient has accessed the hospital. These factors are mainly related to admission procedures,36 bed availability,37 having a flexible appointment in outpatient departments,38 and cooperative staff.39 Organizational factors that impede access are referred to as “Organizational Services Access” (OSA) in this research.

Effectiveness of treatment in healthcare organizations

Some medical professionals and health care researchers have expressed concerns about the effectiveness and appropriateness of many contemporary and emerging medical practices. Effective outcomes provide the practical and relevant evidence that is needed to inform real-world healthcare decisions regarding patients, providers, and policymakers. The main difference between doing things right (to achieve short-term goals, such as accreditation) and doing the right thing (to ensure permanent improvement in long-term goals, such as community prosperity and individual well-being) is “wisdom.”40 When considering the effective outcomes in health care, two major concepts have been explored: system capability and dependability. Effectiveness is normally associated with the system’s capability to treat the cases clinically well, while dependability is associated with stimulating the management to introduce quality measures and continuous improvement. By doing the right thing for the right reasons, an organization is acting in the best interests of the patient, the staff, the institution, and society in general. Although they should share effective available treatment (TRE), perhaps what differentiates non-accredited hospitals (NACCHs) from ACCHs is that the latter exceeds in communicating QoC tools.

A patient’s experience within the SA healthcare system is positive and encouraging due to its free-for-service, assumed universal, access with high QoC, and also because the MOH both regulates and monitors the system. Together, these factors produce a highly effective system. TRE comprises a patient’s participation in his or her treatment plan41 and options,42 while addressing issues related to medical complications43 and length of stay.44

Once an organization is assessed, there should be certain QoC tools implemented, communicated, and practiced in that organization. These criteria ultimately describe how the hospital depends upon compliance with certain rules and regulations established by accreditation. Ensuring the implementation of beneficial QoC tools encompasses legal and ethical issues in the provider–patient relationship. For example, the right to quality medical care without prejudice,15 a patient’s rights bill,45 and the right to receive high-quality standards of healthcare and treatment15 are all legal considerations. Ethical factors include an individual’s right to privacy,46 nurses’ empathy,47 and physician competence.41 One common approach to measuring health access and effectiveness is through patient assessments, revealing how easy or difficult, effective or ineffective, patients found their experiences with the healthcare services they accessed.

In non-medical institutions, obtaining accreditation is usually associated with better performance.48,49 Research, including the findings from this paper, shows concerningly that patients currently do not effectively participate in healthcare evaluations, particularly when it is supposed to reflect their own well-being and the outcomes of their care.50 Access to healthcare services and their effectiveness are the most functional domains of QoC; they reveal the structural and process outcomes in healthcare systems.

QoL in tertiary care

Complete physical, mental, and social well-being are propositions that underpin “leading health.”51 It is a “reflection of the way that patients perceive and react to their health status and to other, non-medical aspects of their lives.”52 During the evaluation or measurement stages, self-reported outcomes are collected and considered as landmarks for patients, policymakers, and society in general. Though it is a subjective gauge, it is an additional measurement of health outcomes that can provide, for example, physician reporting on improvements in their patients. A single index of health status is both feasible and highly desirable.53

In addition to multidimensional indicators,54 medical care contributes substantially to improving patients’ QoL,55,56 especially in tertiary care. Due to its complexity, which involves multidisciplinary factors and the impact of long periods of time, it is rare to track the outcomes of health programs. For example, Wholey and Hatry57 argued that “few government agencies provide timely information on the quality and outcomes of their major program.” In practical terms, the results tend to reveal how often patients are unharmed rather than how well the hospital has performed. “The change in a patient’s current and future health status that can be attributed to antecedent healthcare” is referred to, according to Donabedian,58 as an outcome. Additionally, he asserts that outcomes “remain the ultimate valuators of the effectiveness and quality of medical care.”59 The functional scale, rather than the numeric, standardized, or client satisfaction scale, is normally conceptualized to measure outcome performance.60

Dominant logic in healthcare standardization

Related to an accepted way of thinking, what a healthcare organization utilizes and adopts to create effective performance is described, in this context, as dominant logic. In essence, it is an interpretation of how a hospital has succeeded or failed. It describes the cultural norms and beliefs that the hospital managers espouse and the standards they adopt. For instance, in hospitals that employ staff from all over the world, standardization is not only useful, it is essential. It ensures that staff members who come from different medical backgrounds will work to a set of uniform and acceptable standards, irrespective of their education or training. In this sense, dominant logic is a common way of thinking about standardization across different departments. Some of the restrictive and rigid protocols adopted by corporations have the unfortunate effect of stifling free thought and innovation, causing health management professionals to consider standards in a one-dimensional, superficial way.

Prahalad and Bettis61 suggested that the manner with which top managers deal with the increasing diversity of strategic decisions in an organization depended on the cognitive orientation of top managers only. Accordingly, process logic consists of the mental maps developed through knowledge and experience in the core health industry. Instead of treating employees as assets who have knowledge and experience, and who can, and should, participate in improving health performance, members of staff are actively discouraged to openly reveal what they believe. Almost all of them are instructed to closely follow certain standards within a specific paradigm, thus perpetuating a 19th century management style which elevates machine activity above human activity.

Delegation of authority is a common function of management. The practice of change management and the authority and delegation of certain powers to subordinates are central in allowing an organization to function as a well-oiled machine.62 The philosophy of standardization is not universally accepted as important,63 but it is a fundamental component of accreditation. Standardization is viewed as a tool that will automatically lead to improvement within a health service; achieving accreditation is seen as concrete evidence of that improvement.9 As indicated earlier, accreditation is directing and controlling health services to bring about continued improvement. However, with so much focus on achieving accreditation, there is very limited opportunity for management to practice basic management functions, such as delegation of authority.

In identifying the dominant logic assumptions of the accreditation criteria, this review proposes that the philosophical basis of accreditation practice is “a barrier to transformational management.”64 From a managerial viewpoint, standardization conflicts fundamentally with the principles of change management. While staff should be encouraged and trained to deliver improvements and innovations to health services, standardization means they are not. Rather management teams that focus on standardization may affect staff behaviors, which actually prevent staff from promoting change and innovation, and thus compromising patient health outcomes.

Patients’ behavior and knowledge

Unawareness of health complications and the absence of certain risks to disease are common in much health research.65–68 Looking at the more common factors that affect a patient’s behavior, it is notable that many factors can be related to personal or social activity.69 Personal health activity (PHA) and social health activity (SHA) are activities related directly to participants’ surroundings and their adoption of personal health lifestyles. The literature does not yet adequately describe the potential capabilities, utility, or components of both types of activities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the frequencies of personal health activities (PHA) and social health activities (SHA) at non-accredited hospitals (NACCHs) and accredited hospitals (ACCHs).

| BEHAVIORS | “YES” RESPONSES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACCHs | NACCHs | Z-TEST STATISTIC | |||||

| n | % | n | % | Z | P | ||

| PHA | Smoking | 66 | 32.10% | 97 | 17.90% | 5.35 | <0.001* |

| Exercising | 24 | 43.30% | 112 | 20.70% | 7.92 | <0.001* | |

| Education | 13 | 60.50% | 350 | 64.60% | −1.36 | 0.175 | |

| Balanced diet | 21 | 62.10% | 161 | 29.70% | 10.58 | <0.001* | |

| SHA | Drug instructions | 83 | 74.10 % | 240 | 44.30% | 9.85 | <0.001* |

| Vaccinations | 16 | 80.50% | 306 | 56.50% | 8.38 | <0.001* | |

| Social network | 24 | 82.00% | 309 | 57.0 0% | 8.81 | <0.001* | |

Note:

Significant difference (P < 0.05) between the participants’ behaviors.

On personal level, PHA includes exercising, not smoking, awareness of health issues, and maintaining a better diet. On social level, SHA endorses activities such as complying with dispensed medicine instructions, encouraging follow-up, receiving basic and periodical family vaccines, and being involved in social ties.

Health activity, whether personal or social, depends on one’s awareness of his or her health risks. The health outcomes related to chronic diseases, however, can often be improved through preventive health educational programs like weight loss or, at a minimum, no further weight gain. Thus, health awareness is to everyone’s benefit.

World Health Organization Quality of Life‐Bref instrument

The definition of health is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) and its domains as a complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being. The WHO Quality of Life-Bref (WHOQOL-Bref) instrument covers all these aspects. Substantial efforts have been made to properly operationalize the sub-concepts of various aspects of life included in the instrument.

The WHO’s definition of health is the most widely spread. While many hospitals are seeking accreditations, their patients’ values, demands, well-being, and desired outcomes are partially overlooked in many health programs. Thus, the framework of this paper is based on utilizing health service outcomes with an emphasis on the WHO’s health definition. The WHOQOL-Bref provides data for both research and clinical purposes. Although it is a relatively brief instrument, its structure allows one to acquire specific information covering many aspects of life. WHOQOL-Bref also enhances decisions on level developments70 and reveals hospital experience. The respondents express how much they have experienced these items in terms of health outcomes. Scores represent one’s personal experience and satisfaction regarding various aspects of life, and of healthcare services.

QoL is a reflection of a patient’s perceptions regarding their well-being. Although most QoL tools consist of health domains, it is rare to explore their outcomes on health services and patients’ well-being. The similarities between QoC and QoL illustrate that both aim to achieve patient-centeredness. Over time, the objectives of both concepts have broadened, and they have started to lose their functionality theoretically and practically. While QoC investigates the structure of the hospital, QoL examines personal perspectives and their associated outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Simple comparisons between quality of care (QoC) and quality of life (QoL).

| ASPECT | QoC | QoL |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Institutionalized care | Personalized care |

| Relating to the illness | Relating to the person | |

| Focusing on minor parts of the patient | Responding to the needs of the whole person | |

| Definition | Temporal condition | Perpetual state |

| Theory | Structural | Holistic |

| Focus | Structure based | Outcomes based |

Methods

A survey was employed to establish research priorities based on two health aspects that provide snapshots of the current state of a healthcare system.71 For the first part, a questionnaire was piloted which evaluated patients’ access to healthcare and the effectiveness of treatment. For the second part, the WHOQOL-Bref was distributed to patients who were about to be discharged (n = 1,200) from eight public hospitals in the Riyadh region of SA. Through cluster sampling, only completed questionnaires (n = 1,059) were processed in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for descriptive and inferential analysis. The tool had been validated and approved to an acceptable degree of reliability. Additionally, personal and social factors that could affect patients’ behaviors were introduced. Ethical approvals were obtained from Monash University in Australia and by the MOH.

The components of QoC and QoL were derived by taking into account the structure, processes, and outcomes model as outlined by Donabedian,72 the WHO,73 and Campbell et al,29 while defining QoC. In this study, QoL was selected as the outcome (the dependent variable) and QoC as the process (independent variable).74 The covariance variables are associated with patients’ behaviors.

Subjects

The first author collected a large cross-sectional stream of data from eight public Saudi hospitals. Eligible subjects were patients who were admitted to specialized clinics, such as cardiology and malignant neoplasm, in four tertiary ACCHs and four tertiary NACCHs in the Riyadh region between February 2011 and June 2011. Twelve-hundred patients were invited to participate in the present study, which explored the effectiveness of their treatment before being discharged from these hospitals.

Data collection

Some hospital inpatients were invited to complete a survey one day prior to being discharged, and the survey asked questions about the patient’s level of satisfaction with the treatment and healthcare services received.

The questionnaire explored the demographic and social characteristics related to the actual healthcare treatment that the patient received (Table 2). The questions were related to treatment and hospital standards, and were scored on a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging between total agreement and total disagreement.

Table 2.

Summary of the questionnaire contents.

| DEMO* | BEHAVIOR | ACCESS | EFFECTIVENESS | QoL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERSONAL | SOCIAL | FUNCTIONALITY | AVAILABILITY | CAPABILITY | INDEPENDENCE | WELL-BEING | ||||

| PHA | SHA | TSA | OTA | TRE | QOC | PYS | PSY | SOC | ENV | |

| Factors: 11 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 8 |

| Age | Smoking | Medication | Outcomes | Admission | Opinion | Safety | Pain | Positive | Personal | Financial |

| Gender | Exercise | Vaccination | Referral | Bed | Treatment | Confidentiality | Fatigue | Negative | Sex | Information |

| Nationality | Education | Networks | Follow-up | OPD | Procedures | Rights | Sleep | Esteem | Social | Leisure |

| Insurance | Diet | Cooperation | Complications | Empathetic | Medications | Concentration | Home | |||

| Statues | LOS | Competency | Mobility | Image | Access | |||||

| Education | Standards | Activities | Spirituality | Safety | ||||||

| Occupation | Capacity | Environment | ||||||||

| Income | Transport | |||||||||

| Residency | ||||||||||

| Access | ||||||||||

| Preference | ||||||||||

Demo = Demographic characteristics.

Subject recruitment

The most common method for subject recruitment used in this research was through liaison with the Research Department in Riyadh Health Affairs. At the first level, this involved accessing the major hospitals through RHD to contact the chief executive officers (CEOs) in tertiary hospitals to facilitate the dissemination of the questionnaire, and finally, collecting the questionnaires from the CEOs’ offices. The second and third levels require further clarification.

Each hospital’s CEO was invited to take part in this study. They were informed about the research and its objectives at their hospital by the ethical committee of the MOH, and various staff members were allocated to coordinate this study. The nursing department head, quality specialists, social services personnel, and other key persons were appointed to disseminate and collect the data from patients and forward it to the RHD. The researcher provided brief instructions and information about the nature of the research, its objectives, importance, and how patients might respond to each question. Liaison personnel agreed to meet the sample specifications and to follow the recruitment procedures and timescales on a stage-by-stage basis. It was emphasized that participation in this research was voluntary, and that participants could withdraw at any time. Participants’ responses to the questionnaire were anonymous. Facilitators became the only channel through which to distribute the questionnaires to the participants. Communication between the patients and the facilitators was based on certain criteria, and conditions were established to which both parties were asked to adhere.

Participants were strongly encouraged to fill in the questionnaire independently and without any interference from the researcher or any member of the hospital. Were any ambiguous statement or prejudice evident, participants were encouraged to contact the liaison. The researcher was not directly involved with the patients. There was only a brief session between the researcher and the hospital facilitators. The facilitators were also encouraged to fully understand each question and to check that each questionnaire was collected and placed in a specific envelope without identifying the respondent’s details. In the final stage, the researcher dealt mainly with the CEO’s office in each hospital. The recruitment process took almost five months, at which point all relevant data had been finalized.

Ethics

The study was approved by the MOH, SA, and Monash University. The first author was affiliated with Monash University while conducting this study. Data collection did not include any personal information that could identify the participants. All data remained confidential.

Statistical analysis

Participants’ demographics were summarized using descriptive statistics. For ordinal and nominal data, normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The median of the cumulative access and effectiveness scores were calculated for both groups. Nonparametric inferential tests were performed using the methods described by Sheskin75 and implemented in SPSS version 19.0 using the protocols described by Field.76

Predictor variables consisted of patients’ demographic data and patients’ healthy behaviors, while the dependent variables included items related to physical, mental, social, and environmental well-being. Valid percentages were used to overcome missing data problems. Frequency distributions in ACCHs and NACCHs were described and compared. Finally, the mean score of patients’ overall reports of their respective treatments was stated.

Results

Out of 1,200 questionnaires, only 1,059 were valid for analysis using basic and inferential analysis. The distribution of the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents is described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

| CRITERIA | NUMBER | PERCENTAGE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 630 | 59.5% |

| Female | 429 | 40.5% | |

| Age (years) | 20≤ | 68 | 6.4% |

| 20–60 | 817 | 77.2% | |

| 60≥ | 174 | 16.4% | |

| Nationality | Citizen | 807 | 76.2% |

| Non-citizen | 252 | 23.7% | |

| Marital status | Single | 733 | 69.2% |

| Married | 280 | 26.4% | |

| Divorced | 46 | 4.3% | |

| Level of education | No official education | 332 | 31.3% |

| High school or below | 634 | 59.8% | |

| More than high school | 93 | 8.8% | |

| Occupation | Government sector | 507 | 47.8% |

| Business sector | 476 | 44.8% | |

| Unemployed | 76 | 7.17% | |

| Health insurance | Yes | 148 | 13.9% |

| No | 911 | 86.1% | |

| Income | No income | 104 | 9.8% |

| Less than SR 5.000 | 540 | 51.0% | |

| Between SR 5.000–10.000 | 331 | 31.3% | |

| More than SR 10.000 | 84 | 7.93% | |

| Living in | Riyadh | 771 | 72.8% |

| Other territory | 288 | 27.2% | |

| Accessing | ER | 311 | 29.3% |

| Referral | 339 | 32.0% | |

| Others | 409 | 34.20% | |

| Preference | Public hospitals | 627 | 59.2% |

| Private hospitals | 298 | 28.1% | |

| Both | 86 | 8.12% | |

| Others | 48 | 4.53% | |

| Total | 1059 |

Behavioral characteristics of the patients

The Z-test statistics, based on the frequencies of the “yes” responses to questions about PHA and SHA behaviors, indicated that a significantly higher proportion of the patients at ACCHs reported healthy personal behaviors than those at NACCHs (Table 4). The frequency distributions of the number of healthy behaviors of the patients at the two types of hospitals were significantly different (Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic = 6.689; P < 0.001).

QoC and QoL in health care

Twenty-seven outliers identified by Mahalanobis distance statistics at P < 0.001 were excluded before the regression analysis was performed. The regression statistics are presented in Table 5 for the ACCHs.

Table 5.

Multiple linear regression model to predict quality of life (QoL) for patients at accredited hospitals (ACCHs).

| VARIABLE | STANDARDIZED COEFFICIENTS β | t | P | COLLINEARITY VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.306 | 16.840 | 0.000* | |

| Behaviors | 0.162 | 4.042 | 0.000* | 1.023 |

| TSA | 0.226 | 4.990 | 0.000* | 1.316 |

| OSA | −0.009 | −0.176 | 0.860 | 1.566 |

| TRE | 0.120 | 2.246 | 0.025* | 1.818 |

| QoC | 0.178 | 3.804 | 0.000* | 1.400 |

Adjusted R2 = 19.3%; F = 25.748; P < 0.001; f2 = 0.239.

Based on the responses of the patients at ACCHs, the multiple linear regression (MLR) model explained 19.3% the variance in QoL. The effect size given by f2 = 0.239 was medium, implying that the model had only moderate practical and theoretical significance. The variance inflation factor (VIF) statistics were <3, indicating that the independent variables were not highly collinear. All of the β coefficients were significantly different from zero at P < 0.05 except for β = −0.009 for OSA. Consequently, patients’ access to OSA was not a significant predictor of QoL for patients at ACCHs. Violation of the assumption of homogeneity of variance was reflected by the unequal distribution of residuals on either side of their mean value. There were also several large outliers (i.e., excessively large or small residuals), which could bias the results. Consequently, the inferences that could be made from the results of the regression analysis were compromised and could be misleading.

Based on the responses of the patients at NACCHs, the MLR model (Table 6) explains the 13.5% variance in QoL. The effect size given by f2 = 0.156 was medium, implying that the model had only moderate practical and theoretical significance. The VIF statistics were <3, indicating that the independent variables were not collinear (i.e., they were not strongly intercorrelated with each other). All the β coefficients were significantly different from zero at P < 0.05, except for behaviors (β = 0.010). Patients’ behaviors were not a significant predictor of QoL.

Table 6.

Multiple linear regression model to predict quality of life (QoL) for patients at non-accredited hospitals (NACCHs).

| VARIABLE | STANDARDIZED COEFFICIENTS β | t | P | COLLINEARITY VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.529 | 33.079 | 0.000* | |

| Behaviors | 0.010 | 0.243 | 0.808 | 1.047 |

| TSA | −0.129 | −3.017 | 0.003* | 1.149 |

| OSA | −0.371 | −7.183 | 0.000* | 1.672 |

| TRE | 0.351 | 6.646 | 0.000* | 1.747 |

| QoC | 0.155 | 3.240 | 0.001* | 1.422 |

Adjusted R2 = 13.5%; F = 17.817; P < 0.001; f2 = 0.156.

Reflected by the unequal distribution of residuals on either side of their mean value, the inferences that could be made from the regression coefficients were, however, compromised by violation of the assumption of homogeneity of variance. Ideally, there should be a random scatter of residuals with no geometric pattern. The wedge-shaped pattern of the residuals reflected heteroskedacity (i.e., the variance increased as the predicted value of Y increased). There were several deleted outlier (i.e., excessively large or small residuals) results. Since Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) analysis is based on sums of squares, the squaring of the outliers would generate statistical bias.

The relationships between QoC and QoL

The assumption that logarithmically transformed dependent and independent variables were normally distributed was tested visually, using frequency distribution histograms. Although they deviated from perfect normal distributions, as indicated by bell-shaped curves, all but one of the frequency distributions were sufficiently bell-shaped to assume approximate normality for the purposes of parametric statistics. The frequency distribution of behaviors, however, clearly deviated from normality, which could potentially compromise the results in terms of correlation and regression (Table 7).

Table 7.

Multiple linear regression model to predict quality of life (QoL).

| VARIABLE | STANDARDIZED COEFFICIENTS β | t | P | COLLINEARITY VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.404 | 29.277 | <0.001* | ||

| χ1 | Behavior | 0.109 | 3.365 | 0.001* | 1.257 |

| χ2 | TSA | 0.116 | 3.756 | <0.001* | 1.138 |

| χ3 | OSA | −0.113 | −3.143 | 0.002* | 1.530 |

| χ4 | QoC | 0.138 | 3.781 | <0.001* | 1.588 |

| χ5 | TRE | 0.189 | 4.922 | <0.001* | 1.762 |

| χ6 | Provider | −0.261 | −8.248 | <0.001* | 1.198 |

Adjusted R2 = 0.136; F = 28.092; P < 0.001.

The model explained 13.6% of the variance in QoL, which is a relatively moderate effect size. The t-statistics indicated that all of the independent variables were statistically significant (different from zero) at P < 0.01. The VIF statistics between 1.138 and 1.762 indicated that there was little collinearity between the independent variables. The model using standardized regression coefficients was as follows:

| (1) |

where γ = Logt QoL; χ1 = Logt Behavior; χ2 = Logt TSA; χ3 = Logt OSA; χ4 = Logt QoC; χ5 = Logt TRE; χ6 = Accreditation.

The largest regression coefficient was β6 = −0.261, implying that hospital type was the most important predictor of the variance in QoL, followed by β5 = 0.189 for TRE, and β4 = 0.138 for QoC. Access was less important, as indicated by β2 = 0.116 and β3 = –0.113, while behavior was the least important predictor, as indicated by β1 = 0.109. While all variables are kept constant in Logt10, surprisingly the result suggests that the multiplicative factor of QoL is decreased by 26.1% when the patient is admitted to an accredited facility.

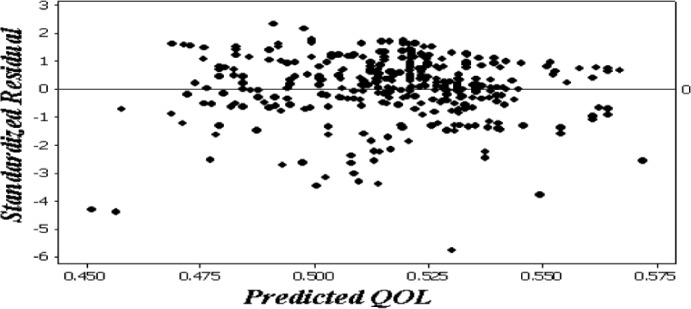

The residuals deviated from normality and were not evenly distributed on either side of their mean values, reflecting non-homogeneity of variance (Fig. 1). Consequently, the data violated the assumptions of MLR, implying that the statistics were biased, and the interpretation could be misleading.

Figure 1.

Non-homogeneity of variance of predicting quality of life (QoL).

Discussion

While the results have shown reasonable evidence regarding the implementation of QoC in most hospitals, the participants’ reports have demonstrated a largely similar view, with partially negative connotations and sometimes outright conflict with QoL. The relationship between implementing QoC and obtaining high levels of QoL with a focus on health accreditation outcomes remains fairly limited. Taking its findings from the perceptions of pre-discharge patients in tertiary public hospitals who volunteered to take part, this study tackles the structural components of QoC and associates them with patients’ QoL. It is suggested that further research may wish to explore this trend, perhaps by refining the accreditation performance of particular chronic cases in other healthcare systems.

In a publicly funded healthcare system, there is a trend to seek accreditation from national and international agencies. The MOH has endeavored to treat communicable and non-communicable diseases statewide. Management is committed to encourage health institutions to improve their overall performance by adopting contemporary healthcare standards. Indeed, both ACCHs and NACCHs seek better outcomes. Consequently, healthcare management is under pressure to fill the gap between treating current cases and improving performance. This is perhaps one interpretation of the identical result in the first phase. Another justification for such a consistent result is that health policy and quality improvements have focused on quick results while conducting their survey. There is, at the same time, a homogeneity of medical cases and of the demographic characteristics of the participants, which may yield the same result.

Both settings revealed a minor influence on achieving QoL. This study is similar to Patrick et al77 who found out that a patient’s functional status correlated moderately with certain health outcomes. Other researchers78 have concluded a positive association between the quality of the treatment component and health-related QoL for certain groups of patients. Even when dealing with elements of quality improvement goals, such as the decrease in medical errors, accreditation has not yet indicated any association.79 In an attempt to identify the prevalence of medication errors (parts of QoC) in ACCHs and NACCHs, Barker et al79 found that there was no significant difference in the error rates for either setting.

The availability of medical treatment has shown a negative association with QoL. The psychological approach to chronic diseases varies from one nation to another, where culture and ethnicity play a major role.80 As part of access availability in QoC, the OSA has shown unfavorable consequences on many participants’ QoL. Patients admitted that those who attend a tertiary hospital were more likely to undergo perpetual procedures, treatments, and most of the time, they would be cared for by the same staff. That participants failed to achieve better outcomes within a hospital facility may be attributed to not focusing enough on the potential positive outcomes of their illness.81

Although accreditation is still voluntary in many countries, including SA, it has become “statutory and most new programs are government-sponsored.”82 Instead of expecting better QoL after accreditation, this study shows that accreditation does not increase participants’ well-being. When health is funded and operated by one resource, there is an ethical consideration where a real conflict of interest unintentionally occurs. Instead of focusing on achieving tangible services for patients, some health institutions have worked under pressure to achieve accreditation, believing that it alone would deliver dominant and fruitful outcomes for patients. Although it reinforces the safety culture of a healthcare system,83 the health accreditation process has recently diverged slightly from the real mission of health, including pain alleviation and well-being, to focus on more financial and administrative burdens.84

Even among some healthcare professionals, the potential benefits of health accreditation are often associated with where the program is run.85 Under the spotlight of ethics, the stated purpose of accreditation of “safeguarding the public”86 is debatable. Alkhenizan and Shaw87 concluded that the CBAHI standards needed a significant modification to meet the international definition of quality, yet no major revisions have yet been made to narrow this gap. Simons et al88 argued that a health service would better manage trauma cases once that service was accredited. However, a conclusion drawn by Øvretveit84 indicated that there is “no guarantee that an organization which is well assessed will always provide high quality care.” In 2007, a report was published by the Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Health and Aging (DOHA),89 which aimed at evaluating the effect of health accreditation on the delivery of QoC and QoL in aged care homes. A conclusion of this report highlighted a positive impact of accreditation on residents’ QoC and QoL.

The present study, however, has weakness and strengths. For example, this study was conducted only in tertiary hospitals. It also investigates a single healthcare episode, where a respondent may have been influenced by consecutive treatments as well as treatments received outside of these hospital. According to Harzing,90 respondents in Arab countries, which exhibit Hofstede’s91 cultural dimensions of a high-power distance, provide a high level of uncertainty avoidance and a strong sense of collectivism. Thus, respondents may attempt to avoid confrontation by generally providing positive or agreeable responses to questionnaires and interviews. In contrast, Minkov92 found that Arab respondents were more likely to exhibit polarized quality judgments in their assessments of current domestic social issues, based on the 2007 Pew Research Centre survey in 47 nations. Additionally, the case in SA might be different from those of other health accreditation processes. One of the principal strengths of this study is its framework. It is rare to trace hospital standards and human well-being; this study explores these relations, and further frameworks are expected to be developed by other researchers in different settings. The domain of practical activities is another strength of this study, where policymakers in the healthcare system may now consider including more practical measures of QoC to improve the overall hospital performance and increase patients’ well-being.

In sum, these findings must be interpreted in light of the functionality of the SA healthcare system. First, patients have fewer options in choosing the hospital type; patients are usually referred to the most clinically suitable hospital. In the standard case, patients are only familiar with the services provided in that hospital, and they are not able to make comparisons to other hospitals. Second, patients face many rules which restrict hospital admissions therefore patients tend to be satisfied when they have been admitted to hospital at all. Overall, most healthcare standards are structurally-based rather than outcomes-based.93 One limitation of this study was that the sample was drawn from very advanced chronic cases. Consequently, participants might be influenced by their pre-existence health conditions. The hospitals were drawn from one region in SA and other locations might lead to the reporting of different experiences. Also, this study was established in a specific geographical context.

Conclusion

The objective of this study was to trace the impact of QoC, particularly in accredited and non-accredited settings, on patients’ well-being. The overall results showed a slight influence on patients’ wellness. Theoretically, like many health research outcomes, one major recommendation is to reform the role of accreditation.94 In this study, the absence of a holistic approach to formulating health accreditation—that is, treating accreditation as an end in itself, and not primarily as a means to improving health outcomes for patients—might have already narrowed our current perspectives. This is a rational view, which holds that an organization is effective only if it achieves specific objectives, and that the performance of a healthcare organization is based on the effective treatment it provides to its patients and the QoC it delivers. There is, however, only a minor influence of health services on a population’s overall health determinants.95

The role and process of healthcare accreditation has deviated from the fundamental aspects of health function and patients’ experiences. While accreditation is a crucial tool in healthcare improvement, it alone will not miraculously transform it, as many people claim. Accreditation should be the means to an end, not an end in itself. Those who extol ‘static accreditation’ as a means of improving patients’ QoL tend to confuse a ‘dominant mind-set’ with ‘actual outcomes’. While rules and regulations should ethically and logically lead to an improvement in patient well-being and better QoL, this research shows that these factors lead to a minor positive result on patient outcomes. Choosing appropriate performance measures is essential, and a continuous evaluation study is needed to obtain definitive results based on actual patient experiences, values, and principles. Such a study would provide independent and unbiased research outcomes, which should then be used to inform the standards used to achieve accreditation.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the first author PhD thesis conducted in Monash University, Australia, funded by King Saud University.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Analyzed the data: WA. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: WA. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: ST. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: WA, ST. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: WA, ST. Made critical revisions and approved final version: ST. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the author has provided signed confirmation of compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Jim Nuovo, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: Authors disclose no funding sources.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Strong K, Mathers C, Leeder S, Beaglehole R. Preventing chronic diseases: how many lives can we save? Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1578–1582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng H. Do people die from income inequality of a decade ago? Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(1):36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9061):1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet] Facts and figures: water, sanitation and hygiene links to health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; [Accessed 10 July 2010]. Available from: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/factsfigures04/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janicki MP, Dalton AJ, Henderson CM, Davidson PM. Mortality and morbidity among older adults with intellectual disability: health services considerations. Disabil Rehabil. 1999;21:5–6. 284–294. doi: 10.1080/096382899297710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordenfelt L. On the goals of medicine, health enhancement and social welfare. Health Care Anal. 2001;9(1):15–23. doi: 10.1023/A:1011350927112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruotsalainen PS, Blobel BG, Seppälä AV, Sorvari HO, Nykänen PA. A conceptual framework and principles for trusted pervasive health. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e52. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walston S, Al-Harbi Y, Al-Omar B. The changing face of healthcare in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28(4):243–250. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(3):172–183. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohr KN, Schroeder SA. A strategy for quality assurance in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(10):707–712. doi: 10.1056/nejm199003083221031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deming WE. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aaronson NK, Acquadro C, Alonso J, et al. International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Qual Life Res. 1992;1(5):349–351. doi: 10.1007/BF00434949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell PH, Ferketich S, Jennings BM. Quality health outcomes model. American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel on Quality Health Care. Image J Nurs Sch. 1998;30(1):43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao PR. Outcomes in healthcare: achieving transparency through accreditation. In: Lee ACG, Carol MF, editors. Measuring Outcomes in Speech-Language Pathology: Contemporary Theories, Models, and Practices. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publisher; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strategic Plan 2010–2020. [Accessed 22 May 2010]. Available from: http://www.MoH.gov.sa/Ministry/About/Pages/Strategy.aspx.

- 16.Searle CM, Gallagher EB. Manpower issues in Saudi health development. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1983;61(4):659–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hospital Accreditation Manual. [Accessed 2 April 2009]. Available from: http://www.cbahi.org/apps/default.aspx?id=142.

- 18.Patient Safety in Anesthesia. [Accessed 13 September 2011]. Available from: http://www.ispub.com/ostia/index.php?xmlFilePath=journals/ijh/vol8n2/safety.xml.

- 19.Auras S, Geraedts M. International comparison of nine accreditation programs for ambulatory care facilities. J Public Health. 2011;19:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies . The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies HT, Lampel J. Trust in performance indicators? Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):159–162. doi: 10.1136/qshc.7.3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfskill SJ. Effectively managing self-pay balances using KPIs. Healthc Financ Manage. 2007;61(4):54–56. 58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor R. Measuring Quality of Life in Health. Sydney, Australia: Churchill Livingstone; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kastrup M, von Dossow V, Seeling M, et al. Key performance indicators in intensive care medicine. A retrospective matched cohort study. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1267–1284. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . The World Health Report 2003—Shaping the Future. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell SM, Hann M, Hacker J, Durie A, Thapar A, Roland MO. Quality assessment for three common conditions in primary care: validity and reliability of review criteria developed by expert panels for angina, asthma and type 2 diabetes. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(2):125–130. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sack C, Scherag A, Lütkes P, Günther W, Jöckel KH, Holtmann G. Is there an association between hospital accreditation and patient satisfaction with hospital care? A survey of 37,000 patients treated by 73 hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(3):278–283. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1611–1625. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxwell RJ. Quality assessment in health. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288(6428):1470–1472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6428.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spertus JA, Bonow RO, Chan P, et al. ACCF/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures ACCF/AHA new insights into the methodology of performance measurement: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on performance measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(21):1767–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute of Medicine . Access to Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitehead M, Dahlgren G, Evans T. Equity and health sector reforms: can low-income countries escape the medical poverty trap? Lancet. 2001;358(9284):833–836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05975-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McBride D, Hardoon S, Walters K, Gilmour S, Raine R. Explaining variation in referral from primary to secondary care: cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c6267. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization . Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao J, Tang S, Tolhurst R, Rao K. Changing access to health services in urban China: implications for equity. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16(3):302–312. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skowronski GA. Bed rationing and allocation in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7(6):480–484. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200112000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altuwaijri MM, Sughayr AM, Hassan MA, Alazwari FM. The effect of integrating short messaging services’ reminders with electronic medical records on non-attendance rates. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(2):193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terraza-Núñez R, Toledo D, Vargas I, Vázquez ML. Perception of the Ecuadorian population living in Barcelona regarding access to health services. Int J Public Health. 2010;55(5):381–390. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell A. On learning and the systems that facilitate it. Center for Quality of Management Journal. 1999;2(5):27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carr SJ. Assessing clinical competency in medical senior house officers: how and why should we do it? Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(940):63–66. doi: 10.1136/pmj.2003.011718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams MT, Domanico J, Marquez L, Leblanc NJ, Turkheimer E. Barriers to treatment among African Americans with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(4):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Qahtani S, Al-Dorzi HM. Rapid response systems in acute hospital care. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5(1):1–4. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.58952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Everett G, Uddin N, Rudloff B. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay for community internists, hospitalists, and academicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):662–667. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almoajel A. Hospitalized patients awareness of their rights in Saudi governmental hospital. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research. 2012;11:329–335. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spiegel M, Pechlaner C. Quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1866–1868. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200311063491916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alligood MR, May BA. A nursing theory of personal system empathy: interpreting a conceptualization of empathy in King’s interacting systems. Nurs Sci Q. 2000;13(3):243–247. doi: 10.1177/08943180022107645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu SI, Chen JH. The performance evaluation and comparison based on enterprises passed or not passed with ISO accreditation: an appliance of BSC and ABC methods. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management. 2012;29(3):295–319. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naser K, Karbhari Y, Mokhtar Z. Impact of ISO 9000 registration on company performance: evidence from Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal. 2004;19(4):509–516. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mair FS, May C, O’Donnell C, Finch T, Sullivan F, Murray E. Factors that promote or inhibit the implementation of e-health systems: an explanatory systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(5):357–364. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.099424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet] WHO definition of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Accessed 17 May 2012]. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gill TM, Feinstein AR. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA. 1994;272(8):619–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaplan R, Anderson J, Ganiats T. The Quality of Well-Being Scale: rationale for a single quality of life index. In: Walker SR, Rosser RM, editors. Quality of Life Assessment: Key Issues in the 1990s. Lancaster, UK: Kluwer Academic Publisher; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hajiran H. Toward a quality of life theory: net domestic product of happiness. Soc Indic Res. 2006;(75):31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van den Berg JP, Kalmijn S, Lindeman E, et al. Multidisciplinary ALS care improves quality of life in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2005;65(8):1264–1267. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180717.29273.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Sjödén PO, et al. Chemotherapy improves survival and quality of life in advanced pancreatic and biliary cancer. Ann Oncol. 1996;7(6):593–600. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wholey JS, Hatry HP. The case for performance monitoring. Public Adm Rev. 1992;(52):604–610. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donabedian A. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin LL, Kettner PM. Measuring the Performance of Human Service Programs. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prahalad CK, Bettis RA. The dominant logic: a new linkage between diversity and performance. Strategic Management Journal. 1986;7(6):485–501. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kondalkar VG. Organization Behavior. New Delhi, India: New Age International; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kohn A. The trouble with Rubrics. English Journal. 2006;95(4):12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 64.White KR, Thompson S, Griffith JR. Biennial Review of Healthcare Management. Vol. 11. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2011. Transforming the dominant logic of hospitals; pp. 133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin RH. Relationship between risk factors, knowledge and preventive behaviour relevant to skin cancer in general practice patients in south Australia. Br J Gen Pract. 1995;45(396):365–367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merghani TH, Zaki M, Ahmed AM, Toum IM. Knowledge, attitude and behavior of asthmatic patients regarding asthma in urban areas in Khartoum State, Sudan. Khartoum Medical Journal. 2011;4(1):524–531. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dorresteijn JA, Kriegsman DM, Assendelft WJ, Valk GD. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD001488. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001488.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cameron C. Patient compliance: recognition of factors involved and suggestions for promoting compliance with therapeutic regimens. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24(2):244–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aveling EL, Martin G, Armstrong N, Banerjee J, Dixon-Woods M. Quality improvement through clinical communities: eight lessons for practice. J Health Organ Manag. 2012;26(2):158–174. doi: 10.1108/14777261211230754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheikh MR, Ali SZ, Hussain A, Shehzadi R, Afzal MM. Measurement of social capital as an indicator of community-based initiatives (CBI) in the Islamic Republic of Iran. J Health Organ Manag. 2009;23(4):429–441. doi: 10.1108/14777260910979317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schäfer T, Gericke C, Busse R. Health services research. In: Ahrens W, Pigeot I, editors. Handbook of Epidemiology. New York, NY: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2005. pp. 1473–1543. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization . Monitoring and Evaluation of Health Systems Strengthening: An Operational Framework. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Accessed 23 January 2012]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/HSS_MandE_framework_Nov_2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Owen JM, Alkin MC. Program Evaluation: Forms and Approaches. 3rd ed. New South Wales, Australia: Allen and Unwin; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sheskin DJ. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. London, UK: Sage publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patrick D, Danis M, Southerland L, Hong G. Quality of life following intensive care. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(3):218–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02596335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vladislavovna Doubova Dubova S, Flores-Hernández S, Rodriguez-Aquilar L, Pérez-Cuevas R. Quality of care and health-related quality of life of climacteric stage women cared for in family medicine clinics in Mexico. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barker KN, Flynn EA, Pepper GA, Bates DW, Mikeal RL. Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(16):1897–1903. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stanton AL, Revenson TA, Tennen H. Health psychology: psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:565–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Ridder D, Geenen R, Kuijer R, van Middendorp H. Psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Lancet. 2008;372(9634):246–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.World Health Organization . Quality and Accreditation in Healthcare Services: A Global Review. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 83.El-Jardali F, Dimassi H, Jamal D, Jaafar M, Hemadeh N. Predictors and outcomes of patient safety culture in hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Øvretveit J. Quality evaluation and indicator comparison in health care. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2001;16(3):229–241. doi: 10.1002/hpm.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Russo P. Accreditation of public health agencies: a means, not an end. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(4):329–331. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000278022.18702.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.World Health Organization . Accreditation Guidelines for Educational/Training Institutions and Programmes in Public Health: Report of the Regional Consultation, Chennai, India, 30 January – 1 February 2002. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alkhenizan A, Shaw C. Assessment of the accreditation standards of the Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions in Saudi Arabia against the principles of the International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30(5):386–389. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.67082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Simons R, Kasic S, Kirkpatrick A, Vertesi L, Phang T, Appleton L. Relative importance of designation and accreditation of trauma centers during evolution of a regional trauma system. J Trauma. 2002;52(5):827–833. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200205000-00002. discussion 833–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Department of Health and Aging . Evaluation of the Impact of Accreditation on the Delivery of Quality of Care and Quality of Life to Residents in Australian Government Subsidised Residential Aged Care Homes. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Aging; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harzing AW. Response styles in cross-national survey research: a 26-country study. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management. 2006;6:243–266. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Instructions and Organizations Across Nations. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Minkov M. Nations with more dialectical selves exhibit lower polarization in life quality judgments and social opinions. Cross Cult Res. 2009;43(3):230–250. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Griffith JR, Knutzen SR, Alexander JA. Structural versus outcomes measures in hospitals: a comparison of Joint Commission and Medicare outcomes scores in hospitals. Qual Manag Health Care. 2002;10(2):29–38. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200210020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Worthington W, Silver LH. Regulation of quality of care in hospitals: the need for change. Law Contemp Probl. 1970;35:305–333. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roemer MI. National health systems as market interventions. J Public Health Policy. 1989;10(1):62–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]