Abstract

A plant-based paste fermented by lactic acid bacteria and yeast (fermented paste) was made from various plant materials. The paste was made of fermented food by applying traditional food-preservation techniques, that is, fermentation and sugaring. The fermented paste contained major nutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids), 18 kinds of amino acids, and vitamins (vitamin A, B1, B2, B6, B12, E, K, niacin, biotin, pantothenic acid, and folic acid). It contained five kinds of organic acids, and a large amount of dietary fiber and plant phytochemicals. Sucrose from brown sugar, used as a material, was completely resolved into glucose and fructose. Some physiological functions of the fermented paste were examined in vitro. It was demonstrated that the paste possessed antioxidant, antihypertensive, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy and anti-tyrosinase activities in vitro. It was thought that the fermented paste would be a helpful functional food with various nutrients to help prevent lifestyle diseases.

Keywords: fermentation, functional food, lactic acid bacteria, yeast

Introduction

The major part of Japanese dietary habits was once plant food. However, in recent years, Western-style dietary habits have been adopted, and various so-called lifestyle diseases are currently predominant. Therefore, the development of foods that promote health and wellbeing is one of the key research priorities of the food industry.1

On the other hand, many irregular agricultural products are wasted without consumption in Japan. Effective utilization of such irregular agricultural resources is desired. We focus on fermented pastes, which are produced by food-preserving techniques such as fermentation and sugar-extraction. The nutritional compounds in fermented pastes appear to be easily digested and administrated, because of their fermentation-processes.2,3 We have developed a fermented paste that contributes to good health, while effectively utilizing underused plant materials. Many fermented foods have been studied for their effects on physiological functions in humans.3 However, little is known about plant-based fermented food(s).

In this paper, we studied the manufacturing process, conducted nutritional analyses, and examined some in vitro physiological functions of the fermented paste that we have developed.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of plant-based paste

Plant-based paste fermented by lactic acid bacteria and yeast (the fermented paste) was made of more than 70 kinds of plant raw materials. Fifteen species of lactic acid bacteria were added as a starter (Table 1). Fresh, in-season plant materials, which were taken as extracts, were soaked with brown sugar. Such extracts were blended with powder materials like cereals and seaweeds, ground, and then the prepared plant paste was fermented using lactic acid bacteria and yeast.

Table 1.

Materials of fermented paste.*

| Material name | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar | Saccharum officinarum (Brown sugar), Zea mays and Solanum tuberosum (Oligosaccharide) | 50% |

| Fruits | Prunus americana (Prune), Prunus mume (Mume), Citrus junos (Yuzu), Fragaria ananassa (Strawberry), Malus domestica (Apple), Citrus iyo (Iyokan), Vitis spp. (Grape), Ficus carica (Fig), Diospyros kaki (Persimmon), Actinidia deliciosa (Kiwifruit), Citrus unshiu (Satsuma mandarin), Citrus limon (Lemon), Fortunella spp. (Kumquat), Akebia spp. (Akebia), Vitis coignetiae (Crimson Glory Vine), Myrica rubra (Chinese bayberry), Rubus buergeri (Buerger raspberry), Vaccinium spp. (Blueberry), Rubus occidentalis (Blackberry), Rubus idaeus (Raspberry), Chaenomeles sinensis (Chinese quinces), Prunus persica var. vulgaris (Peach), Pyrus serotina var. culta (Japanese Pear), Elaeagnus spp. (Oleasters) | 23% |

| Vegetables and wild herbs | Cucurbita maxima (Pumpkin), Daucus carota (Carrot), Artemisia princeps (Mugwort), Brassica oleracea (Cabbage, Kale, and Broccoli), Spinacia oleracea (Spinach), Raphanus sativus (Japanese radish), Solanum melongena (Eggplant), Perilla frutescens (Perilla), Lycopersicon esculentum (Tomato), Capsicum annuum (Sweet pepper), Cucumis sativus (Cucumber), Momordica charantia (Bitter gourd), Brassica campestris (Komatsuna, Qing geng cai, and Vitamin-na), Curcuma longa (Turmeric), Mallotus japonicas (Japanese mallotus), Plantago asiatica (Chinese plantain), Hordeum vulgare (Young leaf of barley), Sasa veitchii (Striped bamboo), Arctium lappa (Burdock), Equisetum arvense (Field horsetail), Eriobotrya japonica (Loquat leaf), Corchorus olitorius (Jew’s mallow), Angelica furcijuga (Japanese moutain ginseng), Petroselinum crispum (Parsley), Oenanthe javanica (Japanese parsley), Apium graveolens var. dulce (Celery), Nelumbo nucifera (Lotus root), Cryptotaenia japonica (Mitsuba), Zingiber mioga (Japanese ginger), Asparagus officinalis (Asparagus), Zingiber officinale (Ginger) | 17% |

| Mushrooms | Lentinula edodes (Shiitake mushroom), Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi), Auricularia auricular (wood ear), Grifola frondosa (Maitake mushroom) | 2% |

| Seaweed | Saccharina japonica (Kombu), Undaria pinnatifida (Wakame), Fucus vesiculosus (Fucus), Hizikia fusiformis (Hijiki) | 1% |

| Pulse and cereals | Glycine max (Soybean), Theobroma cacao (Cocoa), Zea mays (Sweet corn), Oryza sativa (Rice) | 6% |

| Lactic acid bacteria | Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. acetotolerans, L. amylovorus, L. brevis, L. buchneri, L. casei, L. fermentum, L. kefiranofaciens, L. plantarum, Lactococcus lactis, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Pediococcus acidilactici, P. damnosus, P. pentosaceus, P. urinae-equi | 1% |

Notes:

Plant-based paste 3-year-fermented by lactic acid bacteria and yeast. Seventy-one species of domestic plant materials were commercially purchased and used for preparing the fermented paste, except Prunus americana (Prune, from USA). Fucus vesiculosus (Fucus, from Norway), Glycine max (Soybean, from USA), and Theobroma cacao (Cocoa, from Malaysia).

Growth of microorganisms

The growth of lactic acid bacteria and yeast, as well as the pH of fermented paste in the first step (0- to 200-days) was determined. Plate count agar with bromocresol purple (BCP) was used to count colonies of lactic acid bacteria, and was incubated at 37 °C for 72 hrs. Potato dextrose agar (PDA) was prepared to count colonies of fungi and was cultured at 30 °C for 6 days. Colony count data was expressed as CFU/g. The fermented paste was diluted by 10% (weight/weight (w/w)) with water and the pH of the diluted solution was measured with a pH meter.

Identification of yeast

For the identification of yeast, samples fermented from less than one year to three years were used. The colonies grown on PDA were picked up and suspended in a solution containing 1% (volume/volume (v/v)) Triton X-100. The solution containing DNA was treated at 99 °C for 10 minutes (min), and a portion of the 28S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) gene was amplified with PCR using ITS1F primer: GTAACAAGGT(T/C)TCCGT, or ITS1R primer: CGTTCTTCATCGATG. The amplified base sequence was determined and identified. The amplification program used was as follows: preheating at 94 °C for 3 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds (sec), annealing at 55 °C for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and finally a terminal extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The DNA products were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator FS version 1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). Homology searches of the obtained sequences were performed with the BLAST program, available at the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) website.

Nutrient analysis

Major nutrient analysis

Three-year fermented paste was used for nutrient analysis. General constituents, minerals, amino acids, vitamins, organic acids, and sugars were analyzed according to the methods of the Japanese Society for Food Science and Technology.4 Neutral dietary fiber was determined according to Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC) after neutralization of the sample.5

Physiological functions

Antioxidative activity and polyphenol content

Zero-year (less than one year), one-year, two-year, and three-year fermented pastes were assayed. Polyphenol was analyzed according to the methods of Dey and Harborn.6 Fermented paste was extracted with 80% acetone, and the extract was determined at 760 nm using spectrophotometer and quantified by comparison with caffeic acid as a standard. For antioxidative activity, fermented paste was suspended in the same quantity of water and the suspension was filtrated. The filtrate was dissolved with 50% (v/v) ethanol. Superoxide dismutase-like activity (SOD-like activity) was determined according to the methods of Myagmar and Aniya.7

Antihypertensive activity

Angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory activity was determined using hippury-L-histidyl-L-leucine (HHL) as a substrate according to the method of Okamoto and colleagues.8 Three-year fermented paste was used. Fermented paste was extracted with the same quantity of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and the extract was lyophilized. ACE from rabbit lung was used as a standard.

Antibacterial activity

Lactobacillus acidophilus NBRC13951, Lactobacillus brevis NBRC3960, Lactobacillus fermentum NBRC3071, Lactococcus lactis NBRC12007, Enterococcus faecalis NBRC3971, Escherichia coli NBRC3301, Salmonella typhimurium NBRC12529, Staphylococcus aureus NBRC3060, Pseudomonas aeruginosa NBRC3080, Vibrio parahaemolyticus NBRC12711, Providencia rettgeri NBRC13501, and Streptococcus mutans NBRC13955 were purchased from the National Institute of Technology and Evaluation, Biological Resource Center, Japan (NBRC). Lactobacillus plantarum THT030701 was purchased from Sceti K. K., Japan. Staphylococcus aureus IID1677 was purchased from International Research Center for Infectious Diseases Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo, Japan (IID). Helicobacter pylori JCM12036 and Porphyromonas gingivalis JCM12257 were purchased from Japan Collection of Microorganisms, RIKEN Bioresource Center, Japan (JCM). The agar media for the assay of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus acidophilus NBRC13951, L. brevis NBRC3960, L. fermentum NBRC3071, L. plantarum THT030701, Lactococcus lactis NBRC12007, Enterococcus faecalis NBRC3971) and Streptococcus mutans NBRC13955 used de man, Rogosa, Sharpe (MRS) agar (OXIOD, England); those of Helicobacter pylori JCM12036 and Porphyromonas gingivalis JCM12257 used blood agar; those of Vibrio parahaemolyticus NBRC12711 used LB agar (polypeptone 1.0% (w/v), yeast extract 0.5%, NaCl 1.0%, agar 1.3%, pH 7.0); those of the other bacteria used nutrient agar (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan) as a standard media. Moreover, test media were mixed 5% (w/v) with three-year fermented paste and standard media described above, and their pH levels were adjusted with NaOH. The mixed agar media were poured into Petri dishes. After solidification, 50 mL of the diluted bacteria were spread on plates containing a sample. Plates were incubated at the respective optimum conditions. After incubation, colonies on the plates were counted.

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 (ovine) was performed using a commercially-available enzyme immunoassay (Colorimetric COX (ovine) Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three-year fermented paste was extracted with the same quantity of PBS and the extract was diluted to the optimum conditions.

Anti-allergy activity

Inhibition of 15-LOX was determined using the Cayman Chemical Lipoxygenase (LOX) Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three-year fermented paste was extracted with the same quantity of PBS and the extract was diluted to the optimum conditions.

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity

Tyrosinase activity was determined with mushroom tyrosinase and 3,4-dihydroxy-D-phenylalanine (L-DOPA) according to the method of Nihei and colleagues.9 Three-year fermented paste was extracted with the same quantity of PBS. The extract was diluted to the optimum conditions. The inhibitory percentage of tyrosinase was calculated.

Results and Discussion

The growths of microorganisms and pH levels in the fermented paste during fermentation period

The fermented paste was made based on a recipe shown in Table 1. The maximum growths of lactic acid bacteria and yeast in the fermented paste during the fermentation period were 5.8 log10 (CFU/g) and 7.4 log10 (CFU/g), respectively. The mass of bacteria and yeast in the paste changed within 2 to 4 log10 (CFU/g). The pH of the fermented paste was 5.4 at 0 days and 4.3 at 90 days.

Moreover, though yeast in the fermented paste was not added artificially as a starter, it was thought that yeast took part in fermentation of the paste. Colonies grown on PDA were picked up, and their 18S ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid (rDNA) (18S rRNA gene) sequences were determined with PCR and the primer for fungal 18S rDNA. Although the colonies were grown in the fermented paste, both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida apicola were thought to be main yeasts. When the yeast identified as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida apicola were cultured on PDA, Saccharomyces cerevisiae produced a smell like alcohol and Candida apicola smelled like fruit (ester). Hanseniaspora osmophila is known to grow in food or drink with high sugar content such as molasses and wine, and was also picked up in the fermented paste. These yeasts contributed to the fermentation of the paste.

Nutrient analysis

Major nutrient analysis

The fermented paste was a fermented food, for which water activity was kept high to prevent the growth of bad bacteria. As a major component of the fermented paste was saccharides, it had a higher viscosity and was low in protein and fat (Table 2). Its pH level was 4.1 and it had a high amount of potassium as it contained a lot of plant materials. It also contained zinc, iron, iodine and manganese, which were microelements. Furthermore, it had 1,900 mg per 100 g of dietary fiber corresponding to the content of figs, asparagus, and komatsuna. Meanwhile, toxic metals such as lead and mercury were not detected.

Table 2.

Nutritional compounds and amino acids in fermented paste.

| Per 100 g | |

|---|---|

| Water content | 34,000 mg |

| Protein | 3,700 mg |

| Lipid | 1,300 mg |

| Carbohydrate | 59,000 mg |

| Ash | 2,200 mg |

| Sodium | 140 mg |

| Potassium | 620 mg |

| Calcium | 130 mg |

| Magnesium | 68 mg |

| Phosphorus | 97 mg |

| Zinc | 11 mg |

| Iron | 3.0 mg |

| Iodine | 3.0 mg |

| Manganese | 1.0 mg |

| Selenium | None |

| Lead | None |

| Total mercury | None |

| Dietary fiber (NDF*) | 1,900 mg |

| Arginine | 90 mg |

| Lysine | 110 mg |

| Histidine | 40 mg |

| Phenylalanine | 140 mg |

| Tyrosine | 70 mg |

| Leucine | 230 mg |

| Isoleucine | 130 mg |

| Methionine | 40 mg |

| Valine | 150 mg |

| Alanine | 150 mg |

| Glycine | 150 mg |

| Proline | 200 mg |

| Glutamic acid | 530 mg |

| Serine | 140 mg |

| Threonine | 120 mg |

| Aspartic acid | 450 mg |

| Cystine | 40 mg |

| Tryptophan | 40 mg |

Notes:

Neutral dietary fiber.

The amino acid composition analysis showed that 18 species of amino acids were contained in the fermented paste. Specially, the contents of glutamic acid and aspartic acid were high.

All analyzed B vitamins (Vitamin B1, B2, niacin, pantothenic acid, B6, biotin, folic acid, and B12) were detected in the fermented paste (Table 3). The quantity of niacin from fermented paste was more than the estimated quantity (0.7 mg/100 g) from its raw materials. More than half of the niacin could have been produced by lactic acid bacteria and yeast, which participated in fermentation of fermented paste. However, the fermented paste did not have vitamin C. Since vitamin C is easily oxidized, it was thought that vitamin C in the fermented paste was oxidized during the fermentation process.

Table 3.

Vitamin content of fermented paste.

| Per 100 g | |

|---|---|

| Vitamin A (retinol equivalent) | 20 μg |

| α-carotene | 25 μg |

| β-carotene | 190 μg |

| Cryptoxanthin | 77 μg |

| Vitamin B1 (thiamin) | 50 μg |

| Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) | 70 μg |

| Niacin | 1,700 μg |

| Pantothenic acid | 190 μg |

| Vitamin B6 | 270 μg |

| Biotin | 12 μg |

| Folic acid | 1.0 μg |

| Vitamin B12 | 0.030 μg |

| Vitamin C | nd |

| Vitamin D | nd |

| Vitamin E (α-tocopherol) | 400 μg |

| β-tocopherol | nd |

| γ-tocopherol | 200 μg |

| δ-tocopherol | 100 μg |

| Vitamin K | 30 μg |

Abbreviation: nd; not detected.

Lactic, acetic, citric, malic, and succinic acids were contained as organic acids in the fermented paste (Table 4). Sucrose from brown sugar, which was used as a material, was completely resolved into glucose and fructose, and isomaltose was detected.

Table 4.

Organic acid and sugar contents in fermented paste.

| Per 100 g | |

|---|---|

| Lactic acid | 0.16 g |

| Acetic acid | 0.090 g |

| Citric acid | 0.20 g |

| Malic acid | 0.13 g |

| Succinic acid | 0.030 g |

| Tartaric acid | nd |

| Fumaric acid | nd |

| Glucose | 21 g |

| Fructose | 16 g |

| Galactose | nd |

| Arabinose | nd |

| Mannose | nd |

| Sucrose | nd |

| Isomaltose | 0.87 g |

Abbreviation: nd, not detected.

Physiological functions

Antioxidative activity and polyphenol content

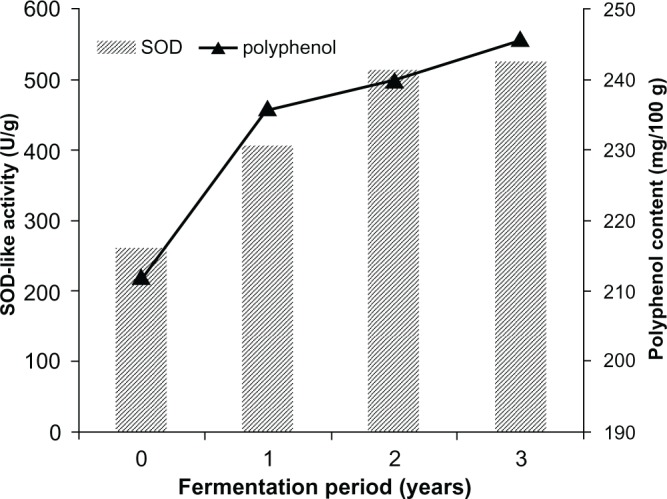

The time course of antioxidative activity (SOD-like activity) and polyphenol content in the fermented paste was determined. Antioxidative activity and polyphenol content were increased step-by-step during fermentation period. Furthermore, there appeared to be a high correlation between antioxidative activity and polyphenol content (Fig. 1). Polyphenol content of the fermented paste (3-year fermentation) was 246 mg per 100 g. This is twice that of red wine (145 mg per 100 g) and 6 times that of cocoa beverage (43 mg per 100 g).

Figure 1.

The time course of antioxidant activity and polyphenol content in fermented paste.

Notes: Pastes from zero-years to three-years were assayed. For antioxidative activity, the fermented pastes were dissolved with 50% (v/v) ethanol. Superoxide dismutase-like activities were determined. Polyphenols of the fermented pastes extracted with acetone were determined by spectrophotometer and quantified by comparison with caffeic acid as a standard.

Antihypertensive activity

The inhibitory activity of the angiotensin conversion enzyme (ACE) was measured in the water-soluble component of the fermented paste. The inhibitory activity of the fermented paste was 61.4% of that of control, and the same extent as that of turmeric (Table 5).

Table 5.

ACE inhibitory activity of 3-year fermented paste.

| ACE inhibitory activity (%) | |

|---|---|

| Fermented paste | 61.4 |

| Bitter gourd | 99.0 |

| Jew’s mallow | 68.6 |

| Turmeric | 63.0 |

| Parsley | 40.7 |

Antibacterial activity

Since the paste was fermented in an open condition like sake, wine, miso, and soy sauce, it was thought that many species of microorganisms would grow, contaminating the fermented paste. However, microbiological control by a traditional food preservation technique and antibacterial compound produced by predominant lactic acid bacteria and yeast in fermented paste suppressed the growth of bad bacteria. Strains and culturing conditions that were used in this assay were shown in Table 6. The fermented paste had no antibacterial activity against Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus brevis, Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecalis and Eschericia coli. When Eschericia coli was assayed on the plate containing 5% of the fermented paste, it did not demonstrate antibacterial activity against Eschericia coli. However, it was confirmed that the fermented paste did not contain Eschericia coli or coliform bacteria. Furthermore, the paste did not demonstrate potential antibacterial activity against Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. This is because the colonies formed on the plates with the paste were smaller than those on the control plates (without the paste). In contrast, there was high antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Providencia rettgeri, and Staphylococcus aureus IID1677. The strain of Staphylococcus aureus IID1677 was tolerant to methicillin. There was also antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. As a result, the fermented paste had antibacterial activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The antibacterial activity of the paste did not change when it was neutralized and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min before the antibacterial test. The molecular weight of the antibacterial compounds was less than 1,000. Organic acids such as lactic acid, acetic acid, citric acid and bacteriocin, which is an antibacterial peptide produced by bacteria, were thought to be the compounds of antibacterial action (Table 4).

Table 6.

Microorganisms and growth conditions used for antibacterial tests, and antibacterial activity of fermented paste.

| Temperature | Incubation time | Condition | Colony account (CFU/plate) | Antibacterial activity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus acidophilus NBRC13951 | 37 °C | 36 hr | Anaerobic | 5%/control* = 1097/908 | – |

| Lactobacillus brevis NBRC3960 | 37 °C | 36 hr | Anaerobic | 5%/control = 577/517 | – |

| Lactobacillus fermentum NBRC3071 | 37 °C | 36 hr | Anaerobic | 5%/control = 132/140 | – |

| Lactobacillus plantarum THT030701 | 37 °C | 36 hr | Anaerobic | 5%/control = 125/148 | – |

| Lactobacillus lactis NBRC12007 | 37 °C | 36 hr | Anaerobic | 5%/control = 138/139 | – |

| Enterococcus faecalis NBRC3971 | 37 °C | 36 hr | Anaerobic | 5%/control = 408/546 | – |

| Staphylococcus aureus NBRC3060 | 37 °C | 18 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 191/289 | Growth inhibition |

| Staphylococcus aureus IID1677 | 37 °C | 18 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 0/201 | + |

| Streptococcus mutans NBRC13955 | 37 °C | 48 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 0/235 | + |

| Escherichia coli NBRC3301 | 37 °C | 18 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 110/112 | – |

| Salmonella typhimurium NBRC12529 | 37 °C | 18 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 20/40 | Growth inhibition |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa NBRC3080 | 37 °C | 48 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 0/290 | + |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus NBRC12711 | 35 °C | 24 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 0/162 | + |

| Providencia rettgeri NBRC13501 | 30 °C | 18 hr | Aerobic | 5%/control = 0/294 | + |

| Helicobacter pylori JCM12036 | 37 °C | 96 hr | Microaerophile | 5%/control = 0/191 | + |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis JCM12257 | 37 °C | 96 hr | Anaerobic | 5%/control = 0/716 | + |

Notes:

5%/control; Comparison between colonies grown on agar media containing 5% of fermented paste and colonies grown on agar media containing 0% of fermented paste.

Anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy, and anti-tyrosinase activities

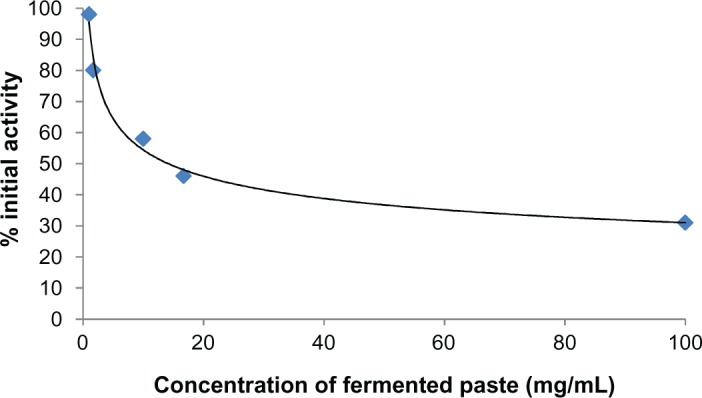

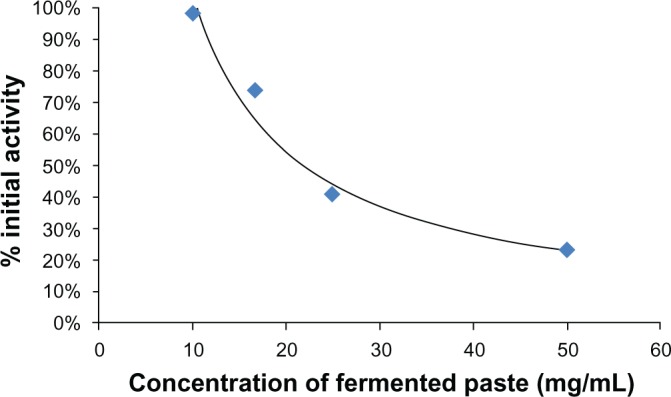

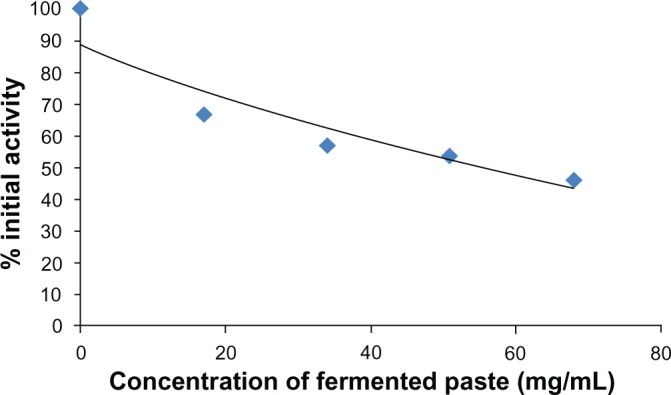

The activity of COX-2 was inhibited by the water-soluble extract of the fermented paste. Its IC50 was 14.2 mg/mL (fresh weight (FW); Fig. 2). The activities of 15-LOX and tyrosinase had the same tendency as COX-2. The activity of 15-LOX was also inhibited by the water-soluble extract of the fermented paste. The IC50 was 21.3 mg/mL (FW; Fig. 3). The activity of tyrosinase was inhibited by the water-soluble fraction. The IC50 was 58.5 mg/mL (FW; Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

COX-2 inhibitory activity of fermented paste.

Notes: Inhibition of COX-2 (ovine) was performed by Colorimetric COX (ovine) Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit. Three-year fermented paste was extracted and diluted with PBS. The activity of COX-2 was inhibited by a water-soluble extract of the fermented paste. The IC50 was 14.2 mg/mL (FW).

Figure 3.

15-LOX inhibitory activity of fermented paste.

Notes: Inhibition of 15-LOX was determined using the Cayman Chemical Lipoxygenase (LOX) Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit. Three-year fermented paste was extracted and diluted with PBS. The activity of 15-LOX was inhibited by a water-soluble extract of the fermented paste. The IC50 was 21.3 mg/mL (FW).

Figure 4.

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity of fermented paste.

Notes: Tyrosinase activity was determined with mushroom tyrosinase and 3,4-dihydroxy-D-phenylalanine (L-DOPA). Three-year fermented paste was extracted and diluted with PBS. The activity of tyrosinase was inhibited by the water-soluble fraction. The IC50 was 58.5 mg/mL (FW).

Conclusion

The fermented paste was made from various plant materials and was fermented by lactic acid bacteria and yeast. The paste was created to be a fermented food in order to be preservable for long time periods, and to provide a supplement with great variety of nutrients. The fermented paste contained not only protein, lipid, and carbohydrate but also minerals, amino acids, vitamins, organic acids and sugars. Moreover, it also contained many phytochemicals as functional ingredients, such as polyphenols and dietary fibers. Polyphenols were known to have various physiological functions such as antioxidative, antibacterial, immunostimulatory, anti-virus, and anti-cancer. Recently they attract great deal of attention as cosmetics, food additives, and pharmaceuticals.10 Since the fermented paste was made using various plant materials, it was thought that it may contain polyphenols. Major polyphenols in it should be identified. The fermented paste also contained amino butyric acid (GABA) as a functional ingredient. As results of physiological function analysis, it had antioxidative, antihypertensive, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy and anti-tyrosinase activities. Since polyphenol content in fermented paste was increasing during fermentation and mature period, the increase of antioxidative activity could be related to the production of melanoidin by Maillard reaction and polymerization of polyphenols. Furthermore, it was suggested that fermented paste had the inhibitory activities of COX and LOX, which were key enzymes with anti-inflammatory and anti-allergy properties, respectively. It was thought that the fermented paste was not only a supplement of various nutrients but also a helpful functional fermented food for the prevention lifestyle diseases.

Acknowledgements

This project was partially supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan though Science and Technology Grant from Okayama prefecture, Japan.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SK. Analysed the data: SK. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: NN, HT, KI. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Funding

Author(s) disclose no funding sources.

Competing Interests

Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication author(s) have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. Any disclosures are made in this section. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Klaenhammer TR, Kullen MJ. Selection and design of probiotics. Int J Food Microbiol. 1999;50:45–57. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(99)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohira I, Nakae T. The isolation and identification of lactic acid bacteria from naturally fermented wild plants and fruits. Japanese Journal of Dairy and Food Science. 1987;36:69–75. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DC, Hwang WI, Jn MJ. In vitro antioxidant and anticancer activities of extracts from a fermented food. J Food Biochem. 2003;27:449–59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura R, et al., editors. New Food Analysis Method. Korin publishing Co; Japan: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emery DF, editor. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists. Ninth Edition. American Association of Cereal Chemists, Inc; St. Paul, USA: 1995. Insoluble Dietary Fiber. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dey PM, Harborn JB, editors. Methods in Plant Biochemistry, Volume 1 Plant Phenolics. Academic Press; Salt Lake City, USA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myagmar BE, Aniya Y. Free radical scavenging action of medicinal herbs from Mongolia. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:221–9. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okamoto A, Hanagata H, Matsumoto E, Kawamura Y, Koizumi Y, Yanagida F. Angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory activities of various fermented foods. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:1147–9. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nihei K, Yamagiwa Y, Kamikawa T, Kubo I. 2-Hydroxy-4-isopropylbenzaldehyde, a potent partial tyrosinase inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:681–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakajima N. Enzymatic stabilization and functionalization of natural-bioactive compounds as the cosmetic materials. Annual Report of Cosmetology. 2004;12:45–51. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]