Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the reliability of clinical grading of vitreous haze using a new 9-step ordinal scale vs. the existing 6-step ordinal scale.

Design

Evaluation of Diagnostic Test (interobserver agreement study).

Participants

119 consecutive patients (204 uveitic eyes) presenting for uveitis subspecialty care on the study day at one of three large uveitis centers.

Methods

Five pairs of uveitis specialists clinically graded vitreous haze in the same eyes, one after the other using the same equipment, using the 6- and 9-step scales.

Main Outcome Measures

Agreement in vitreous haze grade between each pair of specialists was evaluated by the κ statistic (exact agreement and agreement within one or two grades).

Results

The scales correlated well (Spearman’s ρ=0.84). Exact agreement was modest using both the 6-step and 9-step scales: average κ=0.46 (range 0.28–0.81) and κ=0.40 (range 0.15–0.63), respectively. Within-1-grade agreement was slightly more favorable for the scale with fewer steps, but values were excellent for both scales: κ=0.75 (range 0.66–0.96) and κ=0.62 (range 0.38–0.87), respectively. Within-2-grade agreement for the 9-step scale also was excellent [κ=0.85 (range 0.79–0.92)]. Two-fold more cases were potentially clinical trial eligible based on the 9- than the 6-step scale (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Both scales are sufficiently reproducible using clinical grading for clinical and research use with the appropriate threshold (a ≥2 and ≥3 step differences for the 6-step and 9-step scales respectively). The results suggest that more eyes are likely to meet eligibility criteria for trials using the 9-step scale. The 9-step scale appears to have higher reproducibility with Reading Center grading than clinical grading, suggesting Reading Center grading may be preferable for clinical trials.

Uveitis is an important cause of visual loss.1 Treatment of uveitis with anti-inflammatory medication aims to improve or maintain vision by alleviating inflammation. Inflammatory cells and protein exudates in the vitreous make the view of the fundus hazy,2 which usually has been graded by ophthalmoscopy with reference to standard photos3,4 and more recently by grading of color fundus photographs.5 Improvement of vitreous haze is a goal of anti-inflammatory therapy and has been adopted as an appropriate primary or secondary outcome for several clinical trials studying the effect of new treatments on uveitis.6–10 Thus, grading vitreous haze is useful for determining course of patient management and as a quantifiable outcome for clinical trials.

The 6-step ordinal scale developed at the National Eye Institute (NEI) in 1985 for grading vitreous haze was accepted by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group in 2005 as an appropriate scale for use in clinical research; the only change recommended in the original scale was recording the grade of “trace” as 0.5+.3,4 Validation of the 6-step scale has been limited to a small initial study of three observers examining six eyes,3 and a larger study evaluating the scale in a clinical setting, showing modest exact agreement but favorable within-1-grade agreement between one pair of observers (κ value for within-1-grade agreement was 0.75).11 The scale has been implemented in published6–10 and unpublished clinical trials. Many trials have required 2+ or higher vitreous haze for enrollment, in order to permit detection of a change from 2+ to zero haze. In these studies, recruitment has been difficult, because ≥2+ vitreous haze is encountered infrequently in clinical practice.6 In addition, the ordinal scale has been analyzed in some cases as if it were a numerical scale, taking the 0.5+ ordinal step as being 0.5,8,10 which may introduce error given that the steps are not necessarily an equal distance apart, and the 0.5+ step is an ordinal step just like the other steps. While alternative methods for analysis of ordered categorical outcomes exist, they are complicated to implement; thus a scale based on an underlying quantitative foundation would have advantages.

Davis and associates recently proposed a 9-step scale to standardize the grading of vitreous haze using reading center gradings of color fundus photographs.5 The scale offers potential advantages in having more steps (with greater sensitivity to haze differences at the lower end of the scale where most gradings fall); and in being based on a log-linear distribution of image haziness, such that the difference between any 2 steps has the same quantitative meaning. Also, the greater number of steps potentially would broaden patient eligibility for clinical trials in which the goal is to show a ≥2-step difference in vitreous haze. Davis and associates found high inter- and intra-observer agreement (average κ value=0.91 for within-1-grade agreement) using this scale in a Reading Center environment,5 and replicated these findings using baseline images from a major clinical trial, in which vitreous haze correlated well with visual acuity.12 However the scale has not yet been evaluated for its use in a clinical grading environment, which would be less expensive to implement in clinical trials and clinical practice.

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to evaluate inter-grader agreement in clinical grading of vitreous haze, with the goal of more rigorously validating the reproducibility of the existing 6-step scale and also evaluating the reproducibility of the proposed 9-step scale for use in clinical and research settings. The study also directly compares the use of the two scales in clinical settings, and assesses correlations between vitreous haze grade and other clinical characteristics.

Methods

Five uveitis specialists participated from three large uveitis centers that had high numbers of cases with severe inflammation. Each clinician had over ten years in subspecialty practice and previously had participated in multicenter uveitis clinical trials using vitreous haze as an outcome. The specialists reviewed the grading criteria for the 6-step and 9-step scales and completed a brief run-in training session to make sure they had equivalent understanding of the grading process. Pairs consisted of one ophthalmologist paired with each of the five host ophthalmologists. The same patients were evaluated by each clinician in the pair, one clinician after the other. The centers were at the Aravind Eye Hospital, Madurai, India (Center 1, Pair 1); the Post-Graduate Institute, Chandigarh, India (Center 2, Pair 2); and Sankara Nethralaya, Chennai, India (Center 3, Pairs 3–5, grading the same group of patients). The study was conducted after obtaining the required approvals from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pennsylvania, Sankara Nethralaya/The Medical and Vision Research Foundation, the L.V. Prasad Eye Institute, and the Aravind Eye Hospital and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology. The study was conducted in accordance with the precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients presenting for uveitis subspecialty care were examined by each clinician pair as the patients presented, one after the other, without discussing the cases or gradings. Some patients had been asked to come in that day based on an expectation of the host clinician that a high level of vitreous haze would be present. Each pair completed live gradings using the same slit lamp biomicroscopes, indirect ophthalmoscopes, and lenses (equipment which previously had been used in clinical trials). Eyes judged to have a diagnosis of uveitis by at least one grader in each pair, based on findings at the time of the gradings without reference to medical records or the clinician’s memory of the case, were included in the analysis.

For the 6-step scale, vitreous haze was graded following the described method, by comparing indirect ophthalmoscopy findings to a printed poster previously used in a clinical trial displaying standard photos, mentally subtracting the effect of media opacities other than vitreous haze.3,4 For grading using the 9-step scale, indirect ophthalmoscopy findings with the best fundus view obtained were compared to photographs demonstrating the 9 levels shown on a laptop computer screen (the same screen at each center),5 without mentally subtracting the effect of media opacities other than vitreous haze. Additional clinical characteristics that might have affected vitreous haze grade were noted by each ophthalmologist based on slit lamp biomicroscopy, again using the same equipment in succession. These included the presence of central corneal opacities, the degrees of posterior synechiae, and lens status (clear lens, cataract, pseudophakia, posterior capsular opacification, or aphakia). Participants kept their response sheets separate so as to avoid biasing one another. Host clinicians who might have seen the patients previously were instructed to ignore any recollection of previous findings, and to record findings based solely on observations made on the day of examination.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies of clinical characteristics and vitreous haze grade were compiled for all participant eyes, except that comments on uveitis type were ignored for eyes graded to have no uveitis activity (because there was no basis on which to determine what the site of uveitis was in this scenario) The probability of any particular 6-step grading given an observed 9-step grading was modeled using cumulative logistic regression, adjusting only for the grader, applying generalizations of general estimating equations (GEE)13 to account for correlation between the eyes of individual patients (SAS v9.3, SAS Inc., Cary, NC). Inter-observer agreements within each scale and intra-observer agreements between the two scales were assessed using simple agreement and calculation of the κ statistic (Stata 11 Intercooled software, StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). A κ value of 0.00 to 0.20 was considered slight agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 fair, 0.41 to 0.60 moderate, 0.61 to 0.80 substantial, and 0.81 to 1.0 almost perfect agreement.14

Similar to the approach we took in a previous paper evaluating agreement in grading clinical characteristics related to uveitis,11 we evaluated exact agreement and within-1- or within-2-grade agreement (i.e. if two clinicians graded vitreous haze within 1 or 2 grades of each other, that grade was considered to reflect within-1- or within-2-grade agreement respectively). For the 6-step scale, we also evaluated agreement within 1 grade except requiring grades 0 and 4 to have exact agreement (modified-1-grade approach), in an effort to mimic the approach suggested by the SUN Working Group in which a change of 2 grades or else a change of 1 grade to the floor or ceiling of the scale is considered a clinically important degree of change. Weighted κ values were calculated, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated via bootstrapping 1000 times.

Results

The total number of uveitic eyes (patients) graded and included in the final analysis was 44 (30) at Center 1 (Pair 1), 79 (43) at Center 2 (Pair 2), and 81 (46) at Center 3 (Pairs 3–5).

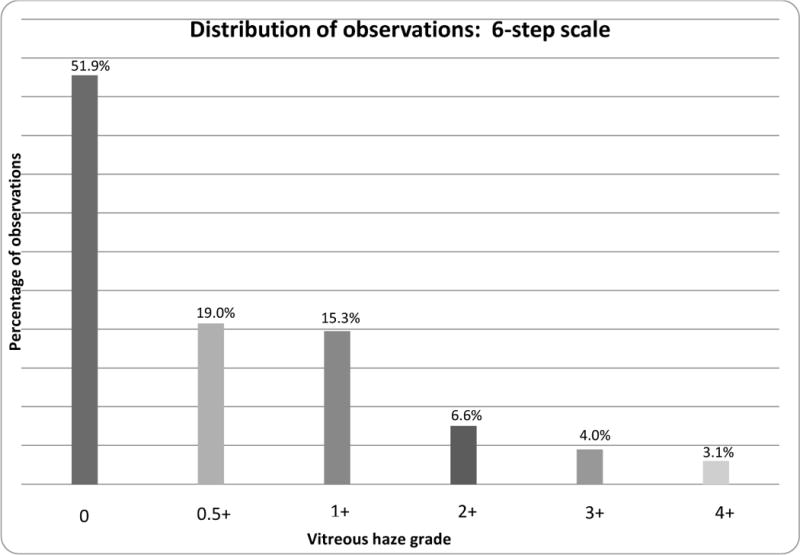

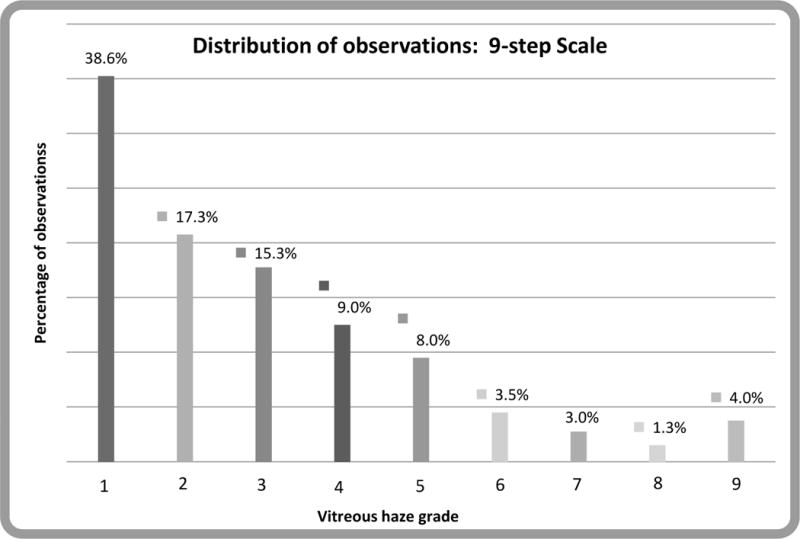

In this group of cases, even though several were asked to come in on the day of evaluation because they were expected to have high levels of vitreous haze, only 14% of uveitic eyes were given a grading of ≥2+ on the 6-step scale (see Figure 1a). Comparatively, 29% and 20% of eyes were given a grading of ≥3 and ≥4 respectively on the 9-step scale (see Figure 1b).

Figure 1a.

Distribution of vitreous haze in eyes with uveitis at all three centers, using the 6-step scale.2,3

Figure 1b.

Distribution of vitreous haze in eyes with uveitis at all three centers, using the 9-step scale.5

Clinicians using the 6-step scale mentally subtract the effect of media opacities when grading vitreous haze. In contrast, when using the 9-step scale, the effect of these media opacities is not mentally subtracted. In our study population, such opacities included central corneal opacity in 3.4% of eyes, ≥180 degrees of posterior synechiae in 8.6% of eyes, and cataract or posterior capsular opacification in 28% of eyes (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Other characteristics in ocular exam.

| Characteristic | % of eyes |

|---|---|

| Central Corneal Opacity | 3.4 |

| ≥180 degrees of posterior synechiae | 8.6 |

| Cataract or posterior capsular opacification | 28 |

| Presence of uveitis activity (including minimal activity) | 59 |

| Site of Uveitis2 | |

| Anterior | 20.83 |

| Intermediate | 18.30 |

| Anterior/Intermediate | 9.80 |

| Posterior | 26.96 |

| Panuveitis | 24.10 |

Exact, within-1-grade, modified-1-grade, and within-2-grade agreement between grader pairs are given in Table 2. For the 6-step scale, exact agreement between the two clinicians in each pair at Centers 1 and 2 was 59% and 89% respectively, with corresponding κ values of 0.39 and 0.81 respectively. At Center 3, exact agreement for Pairs 3–5 was 49%, 58% and 62%, with corresponding κ values of 0.28, 0.40 and 0.41 respectively. Exact agreement between clinicians tended to be lower when using the 9-step scale (with more, finer gradations) than the 6-step scale. At Centers 1 and 2, the weighted κ values were 0.42 and 0.63. At Center 3, the weighted κ values for Pairs 3–5 were 0.38, 0.42, and 0.15 respectively.

Table 2.

Agreement between graders, using alternative standards of agreement. Κ values from 0.00 to 0.20 corresponded to slight agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 fair, 0.41 to 0.60 moderate, 0.61 to 0.80 substantial, and 0.81 to 1.0 almost perfect agreement.7

| Grader pair | Agreement | 6-step Scale Κ Value (range) | 9-step scale Κ Value (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=44) | Exact | 0.39 (0.22–0.57) | 0.42 (0.25–0.58) |

| Modified-1-grade | 0.79 (0.61–0.96) | ||

| Within-1-grade | 0.80 (0.53–1.000) | 0.64 (0.45–0.82) | |

| Within-2-grade | 0.92 (0.69–1.00) | ||

| 2 (n=72) | Exact | 0.81 (0.67–0.93) | 0.63 (0.49–0.76) |

| Modified-1-grade | 0.85 (0.71–0.95) | ||

| Within-1-grade | 0.96 (0.83–1.00) | 0.87 (0.74–0.97) | |

| Within-2-grade | 0.86 (0.70–0.96) | ||

| 3 (n=79) | Exact | 0.40 (0.26–0.54) | 0.38 (0.27–0.50) |

| Modified-1-grade | 0.49 (0.31–0.66) | ||

| Within-1-grade | 0.66 (0.46–0.83) | 0.60 (0.45–0.75) | |

| Within-2-grade | 0.81 (0.66–0.94) | ||

| 4 (n=78) | Exact | 0.28 (0.16–0.43) | 0.42 (0.27–0.56) |

| Modified-1-grade | 0.46 (0.29–0.64) | ||

| Within -1-grade | 0.66 (0.46–0.82) | 0.62 (0.45–0.76) | |

| Within-2-grade | 0.86 (0.71–0.97) | ||

| 5 (n=76) | Exact | 0.41 (0.27–0.56) | 0.15 (0.04–0.26) |

| Modified-1-grade | 0.52 (0.34–0.68) | ||

| Within-1-grade | 0.67 (0.48–0.81) | 0.38 (0.22–0.54) | |

| Within-2-grade | 0.79 (0.61–0.93) | ||

| Average (n=349) | Exact | 0.46 (0.28–0.81) | 0.40 (0.15–0.63) |

| Within-1-grade | 0.75 (0.66–0.96) | 0.62 (0.38–0.87) | |

| Within-2-grade | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) |

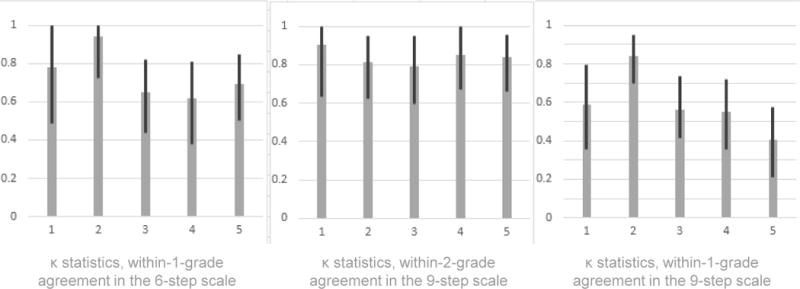

For the 6-step scale, within-1-grade agreement was “substantial” to “almost perfect” for all five pairs of graders (κ of 0.80, 0.96, 0.66, 0.66, and 0.67 for Pairs 1–5 respectively). Modified-1-grade agreement was less favorable, dropping below the “substantial” range in three of five pairs (κ of 0.79, 0.85, 0.49, 0.46, and 0.52 respectively). For the 9-step scale, within-1-grade agreement was slightly less favorable than in the 6-step scale (κ of 0.64, 0.87, 0.60, 0.62, and 0.38 for Centers 1–5 respectively). However, within-2-grade agreement for the 9-step scale (κ of 0.91, 0.81, 0.79, 0.85, and 0.84 for Centers 1–5 respectively) was more favorable than either within-1-grade or modified-1-grade agreement on the 6-step scale (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

κ statistics for agreement in grading indices of ocular inflammation, with 95% confidence intervals. Within-1-grade agreement was slightly less favorable in the 9-step scale than in the 6-step scale; however, within-2-grade agreement for the 9-step scale was the most favorable.

Discussion

Our study found that exact interobserver agreement in clinical grading of vitreous haze is, on average, less than would be desirable for clinical research, whether using the established 6-step scale or the new 9-step scale. However, a favorable degree of agreement occurs when the standard for agreement is relaxed to an appropriate degree for each scale, requiring more relaxation for the scale with finer gradations.

Our results confirmed the reliability of the 6-step scale for clinical studies, replicating four of five times the single prior observation of limited exact agreement, with only one in five pairs having κ≥0.6, but favorable within-1-grade agreement (0.66<κ<0.96) between clinician graders of vitreous haze.11 Modified-1-grade agreement, an attempt to mimic the SUN-promulgated definition of change (where a change from 0.5+ to the floor of 0 or 3+ to the ceiling of 4+ is considered a change), provided slightly less agreement, perhaps reflecting difficulty discriminating between minimal haze and no haze. Thus a simple 2-step change definition may be preferable when using a clinical grading approach.

For the 9-step scale, developed with the intent of using it for photographic (Reading Center) grading, both exact agreement and within-1-grade agreement were less than on the 6-step scale, presumably because adjacent gradations of vitreous haze in the standard photos are closer together for the 9-step than the 6-step scale. Within-2-grade agreement using the 9-step scale was better than within-1-grade agreement using the 6-step scale, but both approaches were favorable. Thus, either scale should be suitable for clinical research based on clinical gradings of vitreous haze, as long as a 3-step change for the 9-step scale and a 2-step change for the 6-step scale are used in order to avoid substantial numbers of cases counted as events based on test-retest variability. Our results suggest that the 9-step scale is less reliable with clinical grading than photographic grading, given that the latter produced outstanding within-one-grade interobserver agreement (κ=0.91).5

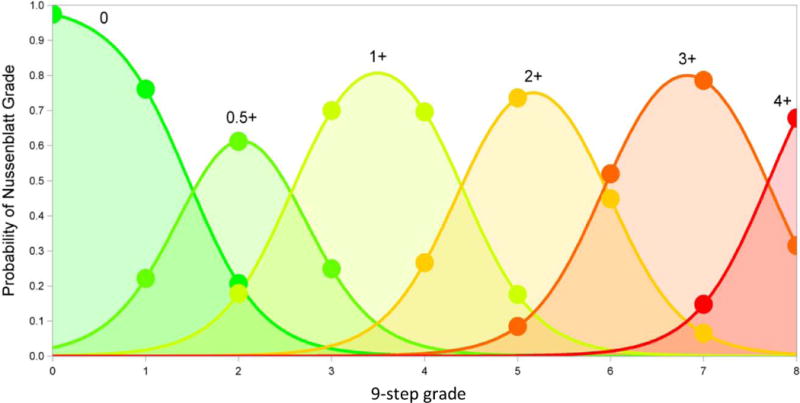

An important advantage of the 9-step scale appears to be discrimination among lower levels of vitreous haze than the 6-step scale, potentially allowing a wider range of cases to be enrolled into a clinical trial. In this study, 29% and 20% of eyes had grade 3 or 4 or higher haze respectively on the 9-step scale, versus 14% with grade 2+ or higher haze on the 6-step scale. Given that the study population came from three centers with a high prevalence of patients with active inflammation, the percentage of subjects meeting enrollment criteria likely would be lower at most centers participating in clinical trials. In addition, many studies necessitate a ≥2-step change in vitreous haze to prove treatment efficacy, a change which would be more easily attained using a grading scale with finer delineations of vitreous haze. Although the two scales correlate with each other, there is sufficient spread in their gradings to prevent the use of a simple conversion factor to compare between them (see Figure 3). Thus, one or the other scale should be used consistently in clinical studies or practices.

Figure 3.

Predicted probabilities of each 6-step grade over the range of 9-step grades. Based on a cumulative logistic regression model for the effect of the continuous 9-step grade on the ordered value of the 6-step grade, adjusted for grader.

A Reading Center approach using the 9-step scale may offer several advantages over clinical grading using either the 6-step or 9-step scales: it has high inter- and intra-observer reliability,5,12 likely would broaden eligibility (and thus simplify recruitment) if grade 3 haze were acceptable, and would permit robust detection of smaller changes in vitreous haze. Broader eligibility may reduce costs to a greater extent than the additional expense of a reading center, as well as enhance generalizability to the broader uveitis population with less extreme levels of vitreous haze. Finally, having auditable images on file could be advantageous for high impact studies, as could the straightforward masking of reading center graders in studies with unmasked ophthalmologists. The main negative of a Reading Center approach would be the slight delay in determining study eligibility; cases would have to be photographed, graded, promptly enrolled, and treated before the level of vitreous haze changed.

A difference between the 6-step and 9-step scales is the latter’s inclusion of non-vitreous media opacities in the overall haze grade: specifically corneal opacities, posterior synechiae, and cataract or posterior capsular opacification.12 With the 6-step scale, clinicians are supposed to mentally subtract these opacities when grading the vitreous.3 The extent to which mental subtraction can be done in a consistent manner is unclear. With the 9-step scale using a photographic approach, if the photographer is unable to adjust the viewing angle to negate the obstruction, the grader would record the apparent haze, having no ability to mentally subtract media opacities. These obstructions produce an additional source of variability in vitreous haze grade, likely affecting clinical grading using either scale as well as photographic grading using the 9-step scale.

Comparisons of haze scores over time assume that media opacities are stationary during the trial, an assumption that may be unjustified with longer follow-up times or with studies comparing treatments that have different effects on media opacities (e.g., cataracts when one treatment is a corticosteroid and the other is not). Information about media opacities should be available and considered when interpreting vitreous haze grades. If the effect of treatments on media opacities is similar, inflating the sample size modestly is likely an adequate compensation for this problem, as changes in media are likely to be unrelated to treatment assignment. If one treatment has a larger effect on media opacities than the other, improvements in vitreous haze in the group receiving treatment with greater effect on media opacity may be obscured, leading to underestimation of the benefit of that treatment for vitreous haze.

Limitations of the study include the possibility of unconscious bias on the part of the host clinician in grading haze of a patient due to prior knowledge of his/her disease condition. However, for the site where two host clinicians participated, the agreement between the hosts was similar (pair 5) to the level of agreement between hosts and the visiting specialist (pairs 1–4). Another limitation is that we attempt to make inferences regarding potential errors in grading over time by comparing agreement between different observers at a single point in time. Also, given that only uveitis specialists participated, agreement might have been more favorable than if non-specialists had participated. However, the results should be generalizable to other specialists who would be participating in clinical trials. Strengths of the study included appropriate sample size and replication of results across multiple centers, which generally agreed. Agreement values were calculated for each center’s set of cases separately, thereby minimizing the potential influence of systematic differences between the eye centers and patient populations on interobserver agreement.

In conclusion, we found limited exact agreement between uveitis specialist graders for the 6-step and 9-step scales, and modest within-1-grade agreement for the 9-step scale, using a clinical grading approach. However, excellent within-1-grade and within-2-grade agreement were noted for the 6-step and 9-step scales respectively. The 9-step scale may have the advantages of finer discrimination of lower levels of haze in clinical use, allowing more patients with lower levels of vitreous haze to be included in studies, and providing a more robust foundation for analyzing results by transposing ordinal steps onto a numerical scale than does the 6-step scale (which in reality is ordinal, not linear). Additionally, given the excellent within-1-grade agreement of the 9-step scale in a Reading Center environment, there are several potential advantages to using this approach in clinical trials rather than either scale with clinical grading, even though the validity of clinical grading using the appropriate design is supported by our results. Both approaches to clinical grading are appropriate for clinical and research use, taking into account these limitations, and their selection (or use of a Reading Center approach with the 9-step scale for studies) can depend on users’ preferences and priorities.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

Support was provided by the Scheie Eye Institute, the Paul and Evanina Bell Mackall Foundation, and Research to Prevent Blindness.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

References

- 1.Rothova A, Suttorp-van Schulten MS, Frits Treffers W, Kijlstra A. Causes and frequency of blindness in patients with intraocular inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:332–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.4.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrester JV. Uveitis: pathogenesis. Lancet. 1991;338:1498–501. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92309-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nussenblatt RB, Palestine AG, Chan CC, Roberge F. Standardization of vitreal inflammatory activity in intermediate and posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:467–71. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis JL, Madow B, Cornett JI, et al. Scale for photographic grading of vitreous haze in uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:637–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowder C, Belfort R, Lightman S, et al. Ozurdex HURON Study Group Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for noninfectious intermediate or posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:545–53. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodaghi B, Gendron G, Wechsler B, et al. Efficacy of interferon alpha in the treatment of refractory and sight threatening uveitis: a retrospective monocentric study of 45 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:335–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.101550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markomichelakis N, Delicha E, Masselos S, Sfikakis PP. Intravitreal infliximab for sight-threatening relapsing uveitis in Behçet disease: a pilot study in 15 patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:534–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen QD, Ibrahim MA, Watters A, et al. Ocular tolerability and efficacy of intravitreal and subconjunctival injections of sirolimus in patients with non-infectious uveitis: primary 6-month results of the SAVE Study. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect [serial online] 2013;3(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1869-5760-3-32. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3610181/. Accessed February 12, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dick AD, Tugal-Tutkun I, Foster S, et al. Secukinumab in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis: results of three randomized, controlled clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:777–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kempen JH, Ganesh SK, Sangwan VS, Rathinam SR. Interobserver agreement in grading activity and site of inflammation in eyes of patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:813–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madow B, Galor A, Feuer WJ, et al. Validation of a photographic vitreous haze grading technique for clinical trials in uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeger SC, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]