Abstract

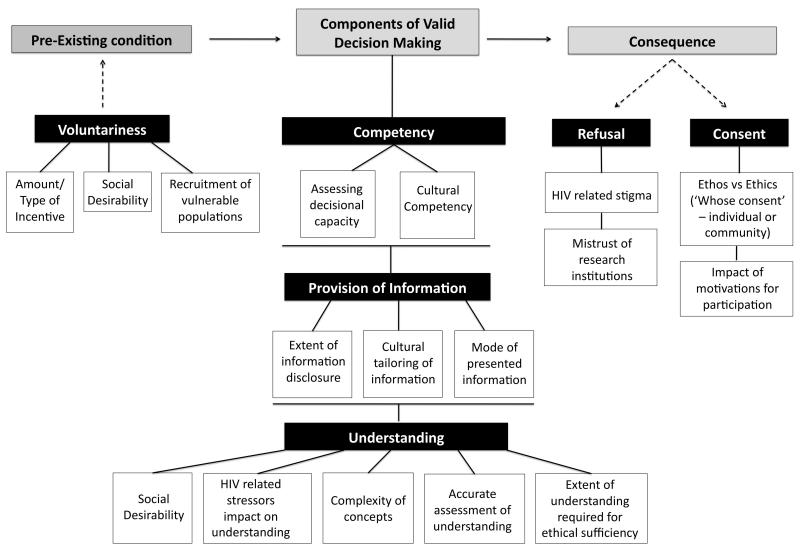

The informed consent (IC) process for HIV vaccine trials poses unique challenges and would benefit from improvements to its historically-based structure and format. Here, we propose a theoretical framework that provides a basis for systematically evaluating and addressing these challenges. The proposed framework follows a linear pathway, starting with the precondition of voluntariness, three main variables of valid decision-making (competency, provision of information and understanding) and then the consequential outcome of either refusal or consent to participate. The existing literature reveals that culturally appropriate provision of information and resultant understanding by the vaccine trial participant are among the most significant factors influencing the authenticity of valid decision-making, though they may be overridden by other considerations, such as individual altruism, mistrust and HIV-related stigma. Community collaborations to foster bidirectional transmission of information and more culturally tailored consenting materials therefore represent a key opportunity to enhance the informed consent process. By providing a visual synopsis of the issues most critical to IC effectiveness in a categorical and relational manner, the framework provided here presents HIV vaccine researchers a tool by which the informed consent process can be more systematically evaluated and consequently improved.

Keywords: HIV Vaccine Trials, Informed Consent, Theoretical Models, HIV vaccine, HIV

Introduction

The informed consent process (ICP) creates the legal and formal record of a person’s willingness to participate in a clinical trial1,2, and as such is integral to all clinical research trials3. Rooted in principles of beneficence, justice and respect for persons4-6, the ICP seeks to obtain true consent, which the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (IOMS) defines as “consent given by a competent individual who has received the necessary information; who has adequately understood the information; and who, after considering the information, has arrived at a decision without having been subject to coercion, undue influence or inducement, or intimidation7.”

The structure and basic format of the ICP has changed little over time4 and has been slow to adapt to changes in research, emerging health concerns, community attitudes and societal values4,8. Because of the powerful effect of such changes on HIV vaccine research, UNAIDS has created guidelines to govern the ICP in HIV vaccine trials9,10, which reflect the special challenges1,3,9,11-13 associated with such research – including both the sensitive social issues14-17 and complex scientific concepts1,9,14,18 that must be conveyed to trial participants. In addition, HIV vaccine trials face other ethical dilemmas, such as the extent of treatment offered to people who become HIV infected during course of a study19-24. These challenges have been well documented in review studies3,9,25, but there is presently no formal conceptual framework that comprehensively incorporate these issues. Such a framework could have considerable value in defining the components of a system, and thereby revealing opportunities for overall optimization and tailoring to the needs of specific study populations.

Subjective Model of Informed Consent by Meisel at al.26

Meisel et al.26 propose a theoretical psychological model of ICP based on the elements of valid decision-making for clinical trials. The authors describe four main variables that comprise valid decision-making: provision of information, competency, understanding, and voluntariness. The latter is a precondition for the first three, which together form the basis for the consequential outcome (consent or refusal).

Voluntariness means that the person making the decision must be free from coercion, unjust persuasions and enticements. Provision of information requires that the participant must be informed on the risks, benefits of participation, potential side effects and alternative treatments if applicable. Competency refers to the person’s capacity to make a valid decision (i.e., is the person capable and reasonably able to make the decision and free from decision-impairing influences such as cognitive disability). Understanding speaks to whether a person comprehends the information that is provided to the extent of knowing the ramifications of their participation. The consequential outcome should follow the steps prior to it and is the patient making a well-reasoned and informed choice to consent to receive the study intervention - or refusal.

The proposed framework does not intend to change the traditional concept of informed consent (IC), but rather seeks to visually depict the process components of IC and related challenges in HIV vaccine trials, and provide a needed structure for strategic evaluation (Figure 1). Major advantages of the framework are that its components are both comprehensive and easy to extrapolate to the IC in any clinical trial, including preventive HIV vaccine trials.

Figure 1. Theoretical Model of the Informed Consent Process in HIV Vaccine Trials.

This model delineates the critical issues in Informed Consent in HIV vaccine trials and organizes them into relational components within a theoretical framework.

Applying the Theoretical Model of Informed Consent Process to IC in HIV Vaccine Trials Pre-Existing Condition

Voluntariness

HIV disproportionately affects marginalized groups (e.g. societal minorities, impoverished communities, and those with chemical dependency problems)16,27-35. Thus, both Phase I/II safety trials and Phase III efficacy trials of experimental HIV vaccines should ideally be tested in these populations. However, vaccine research involving these vulnerable groups comes with an ethical responsibility to guard against unintended coercion of subjects due to poverty, low educational attainment and/or social status and reduced cognitive capacity3,36. In this light, it is important to note that financial compensation for trial participation is viewed by some trial participants as part of the “informal economy” in marginalized communities16,37,38, and even modest financial incentives may have strong effects on behavior, as related to HIV/AIDS16. Non-financial incentives to participation in HIV vaccine trials may also be significant – and can include improved medical ‘care’ to enrolled volunteers that might otherwise be inaccessible16,18,39.

Monetary incentives can increase willingness to participate in vaccine trials17,18,38,40, yet the nature and amount of incentives remains controversial38. Three main models have been proposed: the ‘wage payment model’, the ‘reimbursement model’ and the ‘market model’11. Unfortunately, none is ideal - and choosing the most appropriate for the specific vaccine trial context is critical. This has traditionally been overseen by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for each individual study, but remains fundamentally a subjective exercise with little in the way of data-driven policy guidelines designed to minimize coercion while maintaining fairness.

Social desirability also affects the authenticity of voluntariness in vaccine trials9,41. Potential participants may feel the need to please others who are perceived to have power (e.g., medical personnel) in order to make a favorable impression9,42,43. This is especially likely for socially vulnerable groups who may be traditionally disempowered. “Fear of reprisal” is also a concern in this regard, as the intended community may feel that not participating or withdrawal may have adverse ramifications from those in authority. Use of community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods, such as the use of community advisory boards (CABs) or other social advocacy groups9 and participation of members of the intended population in research activities, may help in closing the cultural gap between scientists and the community.

Components of Valid Decision Making

Competency

It is generally assumed that individuals who meet inclusion criteria and are free from mental disorders or the immediate influence of substance abuse, are able to make valid decisions44. In making this assumption, researchers may overlook the importance of formally assessing reasoning competencies, and the ability to comprehend study-related information44. The existence of multiple reports of insufficient volunteer understanding in the HIV vaccine literature underscores this concern9,12 and suggests that more formal assessment of decisional competency should be considered in the inclusion/exclusion criteria for HIV vaccine studies, especially in vulnerable populations45. Indeed, it may be possible to take advantage of materials developed in other types of studies (substance abuse, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease46) or, the short validated decisional assessment instrument developed by Jeste et al.47.

The cultural competency of HIV researchers is also a critical issue48,49 and highlights the importance of cultural responsiveness training of trial staff. Participants stand to benefit if ‘cultural reconnaissance’ is conducted during the early stages of trial design (i.e. an investigative and immersive effort to understand the cultural and social context of the trial)11,48-50 so that research practices are more in keeping with their socio-cultural norms. Consistent with this, many research groups have highlighted the value of community level involvement through the requirement of CAB review of protocols in development, 11,23,28,48,51-53, however there remains a need to find a way to guarantee effective community input on a consistent basis.

Provision of Information

HIV vaccine researchers are ethically and legally bound to make volunteers aware of all known individual risks and benefits of study participation, as well as the procedures and the underlying scientific rationale for the study. There is however the issue of unforeseeable risks (a concern for participants and researchers alike) — and whether true consent can be achieved in the absence of knowing such information. However, in keeping with the traditional concept of IC, researchers are ethically required to advise participants of the possibility of unknown immediate and/or long-term risks. Participant understanding of the ‘unknowns’ as an inherent part of clinical trials is crucial, as they must agree to a certain level of potential uncertain risk. However, mechanisms (e.g., external data safety monitoring boards) are in place to continuously monitor and assess all potential risks in order to help ensure the safety of trial participants.

Additional supporting trial information can be provided to participants, however this information and the mode by which it is presented is often left to the discretion of researchers and IRB’s. This can lead to misunderstandings, a failure to appreciate the real world perspective of the target population, researcher-biased information and reduced overall participation9. For example, researchers may not feel obliged to dispel cultural myths that propagate their own end or inform participants of indirect harm that can occur as a result of their participation, as this may discourage enrollment. Most research groups attempt to address this concern by instituting permanent CABs, which function to advise trial staff on community perspectives and needs11,40,48,49,54. CABs in conjunction with regulatory ethics boards may also assist by conducting formal a priori putative assessments to ensure that information being dispended is comprehensive, accurate, free from researcher biases, community-specific, and culturally relevant and appropriate, if true IC is to be obtained in keeping with ethical mandates. . This can significantly improve the quality and relevance of recruitment materials and the ICP – as exemplified by the Carraguard Phase 3 microbicide trial (HPTN 035)11, in which the materials used directly reflected community involvement.

A closely related issue is the vehicle by which trial information is communicated to the community. This is strongly influenced by ethos of a given population group9. Should someone from the community (e.g., an elder or respected leader of the same ethnic or cultural background) present the information to be in keeping with socially accepted norms?9,48,49 To what extent should the representative community member be allowed to speak for the ‘individual’? In what forum should this information be presented (e.g., a community gathering, or the person’s home)? Such questions require further exploration and consideration, especially when researchers from one country (e.g., the U.S.) conduct clinical trials in another nation or region where norms and cultural sensibilities may differ (e.g., South Africa)9,10,27,55. CABs become particularly essential in these cases to ensure that cultural appropriateness is optimally achieved.

It is also important to consider the most effective way to present trial-related information. HIV vaccine researchers have explored media ranging from video55, to audiotapes13, to physical props, to traditional pen and paper approaches. For many vaccine sites, traditional written documents are the medium of choice - but there is a tension with respect to providing sufficient information without overwhelming participants9. Some sites have used a combination of media, with some measure of success13,56 - though Flory and Emmanuel’s systematic review of 42 studies on IC processes revealed that no one method is fool-proof25. Again, CABs and/or community partners play a critical role in informing researchers on best modality of information presentation and what works best for their community peers’ reception.

Understanding

HIV vaccine trials must communicate complex information to participants, including concepts such as vaccine-induced seropositivity9,18,40, which are commonly misunderstood by most trial volunteers15,40 and/or people they come into contact with (medical provider, family, etc). In addition, other topics such as the meaning and need for a placebo group, the actual vs. perceived protective effect of HIV vaccination, and composition of the candidate vaccine are also unclear for many participants13,18,40,55. Scientists have responded to the complexity of these topics by using instructional and educational videos55,57, developing culturally sensitive consent processes11,49, simplifying the consent form through the use of pictures and lower grade language level14,58, combining audiovisual forums56, and using audio tapes13 for participants with lower or negligible literacy59. Despite this, however, there is a general consensus that more effective methods to deliver these complex concepts are needed, and that they should be tailored to participants ‘learning style’ (visual vs. auditory learner for example) and/or cultural persuasions. The preliminary evidence supporting person-to-person extended discussion and test/feedback approaches were described as the more effective methods for improving volunteer understanding in the ICP. Care must be taken however, in the interpretation of the observed improvement in understanding results as rote memorization in understanding assessments may have played a role25.

How volunteer understanding is assessed and the validity of assessment tools are thus central concerns in HIV vaccine trials3,9,12. Current assessments of understanding may only measure rote memorization of information, rather than real understanding12. To address this, a variety of assessments have been developed to better assess understanding - including open-ended questions, more conceptual multiple choice questions, and verbal summation of study material to study nurses12,60-62 - though there is still a concern that a significant number of participants are consenting without fully understanding6,62. This also highlights the issue of whether ethical boards should mandate that researchers dedicate resources to more rigorous assessment protocols or leave it to the judgment of principal investigators that may prioritize budgetary constraints over ethical dilemmas such as thoroughly assessing participant understanding.

There is also a need to define, from an evidence-based standpoint, the appropriate level of understanding that is sufficient for trial enrollment37. In practice, this is achieved by researchers selecting an essentially arbitrary threshold score on an evaluation instrument to which participants must meet to enroll- e.g., a “grade” of 81%55 or 75%63. This approach however, does not consider whether a participant may have failed to understand a small subset of essential concepts. This issue is compounded by the heavily stigmatized nature of HIV17,31,64-66, which can strongly affect understanding67. It is essential that researchers work in concert with the intended community through CABs and other community partners, to raise awareness and communicate accurate information prior to study recruitment 10,15,28,48,68.

Consequence

Refusal and Consent

The choice to refuse or consent to participate in a trial is not often predicated on motivational factors such as altruism and perceived positive incentives to participate17,40,69 rather than the information provided. In such cases, participants may have decided to or refuse to participate even before the consenting process, the latter decision possibly being rooted in underlying mistrust, stigma or negative stereotypes32,33,40. This is understandable in light of widespread popular awareness of current and past research abuses, notoriously, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Guatemala Syphilis study70, and requires that HIV vaccine researchers must rebuild trust during trial procedures such as the ICP33,40. For example, it is well documented that African Americans and Latinos have lower participation rates in HIV vaccine trials16,30 and that investigators must initiate creative approaches to encourage their participation30. Research abuses and issues of mistrust have been documented in many other countries, presenting a formidable barrier to participation in vaccine trials internationally 65.

Finally, there is the matter of individual consent vs. community consent37,50. In the United States individual right to choose is highly prioritized and is culturally the norm, however in more communally minded societies decisions are often made in concert with others – including elders, spiritual leaders, family members and community members9. When a person from such a society gives individual consent, it can be important to determine if this decision is reflective of a community approved choice - since failure to obtain “community consent” may have adverse ramifications for the individual49 and could even lead to termination of enrollment in that particular community11. However it is also important to consider whether a person’s choice is indeed an individual decision rather than one coerced by group influences. Studies have shown that fear about breach of confidentiality is a strong disincentive for participation 54,71. To circumvent these social pressures, measures of confidentiality should be rigidly upheld and individuals reassured that the parameters of their involvement are kept confidential.

Limitations of the Framework

The linear fashion of the framework can limit the application IC as a dynamic process. In its linearity it can suggest that IC goes from point A (voluntariness) to B (decision making) and then end. However, the process of consent can be an ongoing enterprise whereby scientists continually reassess whether a person feels that their decision is voluntary as the trial proceeds, whether they understand the ramifications of their participation and whether more information needs to be provided even after an initial decision is made, to ensure that the person is fully aware, dictating the need for secondary consent. While this may be a limitation of the model, this structure of consent can be applied at various time points along the course of a trial, thus circumventing the apparent finiteness of the proposed model. The model seeks to highlight the primary challenges in HIV vaccine IC but does not include other relevant challenges such as: the evolution of cultural norms towards researcher biases and potential negative consequences of this; how best to assure the competency of investigators in providing accurate information and conducting IC protocols; and to what extent research groups should be held responsible for potential negative consequences of trial participation. Finally, the model still adheres to the traditional concept of consent and may reinforce current ideologies about consent. However, the model is so structured to better capture the current challenges of IC in vaccine trials, which have been bred in the traditional understanding of consent. Changing the fundamental concept structure of consent requires more extensive investigation and the development of evidence-based solutions.

Conclusion

This paper describes a conceptual framework that can be used by HIV vaccine researchers to systematically evaluate and improve IC protocols. Existing consent protocols can be mapped onto the different components of the framework and examined using this perspective, to determine if they are effectively addressing key challenges with respect to the study protocol, target population(s) and individual study participants. By facilitating strategic evaluation, the model challenges researchers to find innovative ways to overcome these existing hurdles, and reform or add to the fundamental structure of consent, to better protect the ethical rights of participants. The model provides a critical synopsis of challenges for participants to consider when engaging in a trial so as to help safeguard their ethical rights. This proposed framework also highlights the importance of carefully considering cultural issues, and working in close collaboration with the community, in order to develop processes that can be tailored to a wide range of research populations/ settings. Ultimately, this framework provides the foundation for the improvement of the ICP for scientifically complex clinical research in vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by the Division of AIDS, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Developmental Center for AIDS Research Grant P30 AI078498 (NIH/NIAID) and the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. The work was also partly supported by the University of Rochester CTSA award number TL1 TR000096 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Cindi A. Lewis, Public Health Sciences, University of Rochester Medical Center, 265 Crittenden Blvd, CU 420644, Rochester, NY 14642, 585-275-0482, cindi_lewis@urmc.rochester.edu

Stephen Dewhurst, Microbiology and Immunology, University of Rochester Medical Center 601 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642 (585) 275-3216, stephen_dewhurst@urmc.rochester.edu.

James M. McMahon, School of Nursing University of Rochester Medical Center 601 Elmwood Avenue Rochester, NY 14642 585-276-3951.

Catherine A. Bunce, Infectious Diseases Dept., University of Rochester Medical Center 601 Elmwood Ave.; Box 689 Rochester, NY 14642 (585) 275-5744, catherine_bunce@urmc.rochester.edu.

Michael C. Keefer, Infectious Diseases Dept., University of Rochester Medical Center 601 Elmwood Ave.; Box # 689 Rochester, NY 14642 (585) 275-8058, michael_keefer@urmc.rochester.edu.

Amina P. Alio, Public Health Sciences, University of Rochester Medical Center, 265 Crittenden Blvd, CU 420644, Rochester, NY 14642, (585) 275-0482, amina_alio@urmc.rochester.edu.

References

- 1.Kahn P, editor. AIDS vaccine handbook: Global Perspectives. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lidz CW. Informed consent: a critical part of modern medical research. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2011 Oct;342(4):273–275. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318227e0cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariner WK. Taking informed consent seriously in global HIV vaccine research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Feb 1;32(2):117–123. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson GE. Is informed consent broken? The American journal of the medical sciences. 2011 Oct;342(4):267–272. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31822a6c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faden RF, Beauchamp TL. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jefford M, Moore R. Improvement of informed consent and the quality of consent documents. The lancet oncology. 2008 May;9(5):485–493. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avrett S, Carroll S, Collins C, et al. HIV Vaccine Handbook: Community Perspectives on Participating in Research, Advocacy, and Progress. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition; Washington, D.C.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padberg RM, Flach J. National efforts to improve the informed consent process. Seminars in oncology nursing. 1999 May;15(2):138–144. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(99)80071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindegger G, Richter LM. HIV vaccine trials: critical issues in informed consent. South African journal of science. 2000 Jun;96:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNAIDS . Ethical considerations in HIV preventive vaccine research: A UNAIDS guidance document. UNAIDS; WHO; Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrory EC, Friedland BA, Woodsong C, MacQueen KM. Informed Consent in HIV Prevention Trials Report of an International Workshop. Population Council Family Health International; New York City: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindegger G, Milford C, Slack C, Quayle M, Xaba X, Vardas E. Beyond the checklist: assessing understanding for HIV vaccine trial participation in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006 Dec 15;43(5):560–566. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000247225.37752.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coletti AS, Heagerty P, Sheon AR, et al. Randomized, controlled evaluation of a prototype informed consent process for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Feb 1;32(2):161–169. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy DA, O’Keefe ZH, Kaufman AH. Improving Comprehension and Recall of Informationfor an HIV Vaccine Trial among Women at risk for HIV: Reading Level Simplification and Inclusion of Pictures to Illustrate Key Concepts. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1999;11(5):389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen M, Lau CY. Social impact of preventive HIV vaccine clinical trial participation: a model of prevention, assessment and intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2008 Feb;66(4):945–951. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman PA, Duan N, Roberts KJ, et al. HIV Vaccine Trial Participation Among Ethnic Minority Communities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:210–217. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179454.93443.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Kegeles S, et al. Willingness to volunteer in future preventive HIV vaccine trials: issues and perspectives from three U.S. communities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001 Jan 1;26(1):63–71. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200101010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koblin BA, Heagerty P, Sheon A, et al. Readiness of high-risk populations in the HIV Network for Prevention Trials to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials in the United States. AIDS. 1998 May 7;12(7):785–793. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald DW, Pape JW, Wasserheit JN, Counts GW, Counts GW, Corey L. Provision of treatment in HIV-1 vaccine trials in developing countries. Lancet. 2003 Sep 20;362(9388):993–994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ethics in HIV vaccine research. Bulletin of medical ethics. 2000 Jul-Aug;(160):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klitzman R. Views of the process and content of ethical reviews of HIV vaccine trials among members of US institutional review boards and South African research ethics committees. Developing world bioethics. 2008 Dec;8(3):207–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berkley S. Thorny issues in the ethics of AIDS vaccine trials. Lancet. 2003 Sep 20;362(9388):992. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher CB. Enhancing HIV vaccine trial consent preparedness among street drug users. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics: JERHRE. 2010 Jun;5(2):65–80. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HN, Tabet SR, Corey L, Celum CL. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial participants who seroconvert. Vaccine. 2006 Jan 23;24(4):532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants’ understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004 Oct 6;292(13):1593–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meisel A, Roth LH, Lidz CW. Toward a model of the legal doctrine of informed consent. The American journal of psychiatry. 1977 Mar;134(3):285–289. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guenter D, Esparza J, Macklin R. Ethical considerations in international HIV vaccine trials: summary of a consultative process conducted by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Journal of medical ethics. 2000 Feb;26(1):37–43. doi: 10.1136/jme.26.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyamathi A, Koniak-Griffin D, Tallen L, et al. Use of community-based participatory research in preparing low income and homeless minority populations for future HIV vaccines. Journal of interprofessional care. 2004 Nov;18(4):369–380. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Djomand G, Katzman J, di Tommaso D, et al. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities in NIAID-funded networks of HIV vaccine trials in the United States, 1988 to 2002. Public Health Rep. 2005 Sep-Oct;120(5):543–548. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobieszczyk ME, Xu G, Goodman K, Lucy D, Koblin BA. Engaging members of African American and Latino communities in preventive HIV vaccine trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Jun 1;51(2):194–201. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181990605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyblade L, Singh S, Ashburn K, Brady L, Olenja J. “Once I begin to participate, people will run away from me”: understanding stigma as a barrier to HIV vaccine research participation in Kenya. Vaccine. 2011 Nov 8;29(48):8924–8928. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of general internal medicine. 1999 Sep;14(9):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of internal medicine. 2002 Nov 25;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moutsiakis DL, Chin PN. Why blacks do not take part in HIV vaccine trials. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007 Mar;99(3):254–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts KJ, Newman PA, Duan N, Rudy ET. HIV vaccine knowledge and beliefs among communities at elevated risk: conspiracies, questions and confusion. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005 Dec;97(12):1662–1671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minnies D, Hawkridge T, Hanekom W, Ehrlich R, London L, Hussey G. Evaluation of the quality of informed consent in a vaccine field trial in a developing country setting. BMC medical ethics. 2008;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.London L, Kagee A, Moodley K, Swartz L. Ethics, human rights and HIV vaccine trials in low-income settings. Journal of medical ethics. 2012 May;38(5):286–293. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slomka J, McCurdy S, Ratliff EA, Timpson S, Williams ML. Perceptions of financial payment for research participation among African-American drug users in HIV studies. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007 Oct;22(10):1403–1409. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colfax G, Buchbinder S, Vamshidar G, et al. Motivations for participating in an HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Jul 1;39(3):359–364. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000152039.88422.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchbinder SP, Metch B, Holte SE, Scheer S, Coletti A, Vittinghoff E. Determinants of enrollment in a preventive HIV vaccine trial: hypothetical versus actual willingness and barriers to participation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 May 1;36(1):604–612. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200405010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartlett CJ, Doorley R. Social Desirability Response Differences Under Research, Simulated Selection and Faking Instructional Sets. Personnel Psychology. 1967;20(3):281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher RJ. Social Desirability Bias and the Validity of Indirect Questioning. Journal of Consumer Research. 1993;20(2):303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams SA, Matthews CE, Ebbeling CB, et al. The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. American journal of epidemiology. 2005 Feb 15;161(4):389–398. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wendler D. Can we ensure that all research subjects give valid consent? Archives of internal medicine. 2004 Nov 8;164(20):2201–2204. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf LE, Lo B. Informed consent in HIV research. Focus. 2004 Apr;19(4):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunn LB, Nowrangi MA, Palmer BW, Jeste DV, Saks ER. Assessing decisional capacity for clinical research or treatment: a review of instruments. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006 Aug;163(8):1323–1334. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, et al. A new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical research. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007 Aug;64(8):966–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woodsong C, Karim QA. A model designed to enhance informed consent: experiences from the HIV prevention trials network. American journal of public health. 2005 Mar;95(3):412–419. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richter LM, Lindegger GC, Abdool Karim Q, Gasa N. Guidelines for the development of culturally sensitive approaches to obtaining informed consent for participation in HIV vaccine-related trials. School of Psychology, University of Natal, UNAIDS; Scottsville, South Africa: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhutta ZA. Beyond informed consent. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004 Oct;82(10):771–777. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mosavel M, Simon C, van Stade D, Buchbinder M. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) in South Africa: engaging multiple constituents to shape the research question. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Dec;61(12):2577–2587. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quinn SC. Ethics in public health research: protecting human subjects: the role of community advisory boards. American journal of public health. 2004 Jun;94(6):918–922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Quinn SC, et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. American journal of public health. 2001 Dec;91(12):1938–1943. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mills E, Nixon S, Singh S, Dolma S, Nayyar A, Kapoor S. Enrolling women into HIV preventive vaccine trials: an ethical imperative but a logistical challenge. PLoS medicine. 2006 Mar;3(3):e94. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joseph P, Schackman BR, Horwitz R, et al. The use of an educational video during informed consent in an HIV clinical trial in Haiti. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006 Aug 15;42(5):588–591. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000229998.59869.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryan R, Prictor M, McLaughlin KJ, Hill S. Audio-Visual presentation of information for informed consent for participation in clinical trials. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003717.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barbour GL, Blumenkrantz MJ. Videotape aids informed consent decision. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1978 Dec 15;240(25):2741–2742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corneli AL, Sorenson JR, Bentley ME, et al. Improving participant understanding of informed consent in an HIV-prevention clinical trial: a comparison of methods. AIDS and behavior. 2012 Feb;16(2):412–421. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9977-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agre P, Campbell FA, Goldman BD, et al. Improving informed consent: the medium is not the message. Irb. 2003 Sep-Oct;25(Suppl)(5):S11–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmer BW, Cassidy EL, Dunn LB, Spira AP, Sheikh JI. Effective use of consent forms and interactive questions in the consent process. Irb. 2008 Mar-Apr;30(2):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shafiq N, Malhotra S. Ethics in clinical research: need for assessing comprehension of informed consent form? Contemporary clinical trials. 2011 Mar;32(2):169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhansali S, Shafiq N, Malhotra S, et al. Evaluation of the ability of clinical research participants to comprehend informed consent form. Contemporary clinical trials. 2009 Sep;30(5):427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sugarman J, Corneli A, Donnell D, et al. Are there adverse consequences of quizzing during informed consent for HIV research? Journal of medical ethics. 2011 Nov;37(11):693–697. doi: 10.1136/jme.2011.042358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mawar N, Saha S, Pandit A, Mahajan U. The third phase of HIV pandemic: social consequences of HIV/AIDS stigma & discrimination & future needs. The Indian journal of medical research. 2005 Dec;122(6):471–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mills E, Cooper C, Guyatt G, et al. Barriers to participating in an HIV vaccine trial: a systematic review. AIDS. 2004 Nov 19;18(17):2235–2242. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411190-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beatty LA, Wheeler D, Gaiter J. HIV Prevention Research for African Americans: Current and Future Directions. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30(1):40–58. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brooks RA, Etzel MA, Hinojos E, Henry CL, Perez M. Preventing HIV among Latino and African American gay and bisexual men in a context of HIV-related stigma, discrimination, and homophobia: perspectives of providers. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2005 Nov;19(11):737–744. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frew PM, Archibald M, Hixson B, del Rio C. Socioecological influences on community involvement in HIV vaccine research. Vaccine. 2011 Aug 18;29(36):6136–6143. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bartholow BN, MacQueen KM, Douglas JM, Jr., Buchbinder S, McKirnan D, Judson FN. Assessment of the changing willingness to participate in phase III HIV vaccine trials among men who have sex with men. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes and human retrovirology: official publication of the International Retrovirology Association. 1997 Oct 1;16(2):108–115. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199710010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zenilman JM. Ethics gone awry: the US Public Health Service studies in Guatemala; 1946-1948. Sexually transmitted infections. 2013 Jun;89(4):295–300. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jenkins RA, Temoshok LR, Virochsiri K. Incentives and disincentives to participate in prophylactic HIV vaccine research. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes and human retrovirology: official publication of the International Retrovirology Association. 1995 May 1;9(1):36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]