Abstract

Studies of remote memory for semantic facts and concepts suggest that hippocampal lesions lead to a temporally graded impairment that extends no more than ten years prior to the onset of amnesia. Such findings have led to the notion that once consolidated, semantic memories are represented neocortically and are no longer dependent on the hippocampus. Here, we examined the fate of well-established semantic narratives following medial temporal lobe (MTL) lesions. Seven amnesic patients, five with lesions restricted to the MTL and two with lesions extending into lateral temporal cortex (MTL+), were asked to recount fairy tales and bible stories that they rated as familiar. Narratives were scored for number and type of details, number of main thematic elements, and order in which the main thematic elements were recounted. In comparison to controls, patients with MTL lesions produced fewer details, but the number and order of main thematic elements generated was intact. By contrast, patients with MTL+ lesions showed a pervasive impairment, affecting not only the generation of details, but also the generation and ordering of main steps. These findings challenge the notion that, once consolidated, semantic memories are no longer dependent on the hippocampus for retrieval. Possible hippocampal contributions to the retrieval of detailed semantic narratives are discussed.

Keywords: semantic memory, narratives, remote memory, amnesia, medial temporal lobes, consolidation

1. Introduction

The study of remote memory in patients with medial temporal lobe (MTL) amnesia provides important insights into the nature of hippocampal-neocortical interactions supporting the formation of durable long-term memories. In recent years, much of this research has focused on the fate of episodic memories, in light of contradictory findings regarding the temporal extent and severity of episodic memory loss following hippocampal lesions. These findings have been leveraged as critical sources of support for competing theories of memory consolidation (Moscovitch, Nadel, Winocur, Gilboa, & Rosenbaum, 2006; Squire, 1992; Squire & Alvarez, 1995; Winocur & Moscovitch, 2011).

Less controversial has been the status of semantic memory following MTL lesions. Studies of remote memory for facts, public events, and personalities typically show either intact remote memory in patients with lesions restricted to the hippocampal region or retrograde amnesia extending at most 10 years (for review, see Fujii, Moscovitch, & Nadel, 2000; Moscovitch, et al., 2006; Winocur & Moscovitch, 2011), although there are exceptions finding a more extensive gradient (Cipolotti, et al., 2001; Reed & Squire, 1998), possibly reflecting the fact that memory for public information can be aided by personal, episodic recollections in healthy participants (Westmacott, Black, Freedman, & Moscovitch, 2004). The temporally graded semantic memory loss in patients with hippocampal lesions stands in contrast to the much more extensive impairment seen in patients whose lesions involve surrounding neocortex (Fujii, et al., 2000; Moscovitch, et al., 2006; Squire & Bayley, 2007; Winocur & Moscovitch, 2011). These findings have been taken to suggest that the hippocampus has a time-limited role in semantic memory. That is, the hippocampus is thought to be critical for initially linking informational elements that are processed in disparate neocortical areas into coherent memories. With repeated re-activation of these hippocampal-cortical interactions, linkages within a distributed neocortical network are strengthened, such that eventually memories can be retrieved without hippocampal mediation (Squire, 1992; Squire & Alvarez, 1995; Squire & Zola, 1998).

Neuropsychological studies exploring the role of the MTL in semantic memory have focused almost exclusively on memory for isolated elements of information. However, important information may also be gained from assessing memory for more complex semantic narratives that require the description of multiple semantic elements in their dynamic unfolding. Moscovitch and Melo (1997) were the first to examine memory for semantic narratives in amnesic patients. They asked a group of patients of mixed etiology to describe in detail historical events in response to a cue word, in a manner parallel to the method used to assess autobiographical memory. Although the primary focus of this study was on confabulation, non-confabulating amnesic patients were also impaired at describing historical events; in fact, their descriptions of historical events were no better than their descriptions of personal autobiographical events. More recently, Rosenbaum and colleagues (Rosenbaum, Gilboa, Levine, Winocur, & Moscovitch, 2009) assessed patient K.C.’s memory for fairy tales and bible stories, and similarly found that his narratives contained many fewer details than those of controls.

In both of these studies, the semantic knowledge was acquired long before onset of amnesia, and as such, the observed impairments stand in contrast to the findings of the semantic fact studies reviewed above, which typically found impairments restricted to knowledge acquired in the recent time period preceding the onset of amnesia. However, the implications of the findings from the narrative studies for the role of the MTL in semantic memory are unclear because the lesions in many of the amnesic patients under study included areas outside the MTL. In our own work (Race, Keane, & Verfaellie, 2013), we recently found that patients with lesions restricted to the MTL, while able to generate non-personal (semantic) issues that were significant in the past (e.g., “When you were growing up, what were the most important issues facing the environment?”), provided much less detail in elaborating on the impact of these issues. This impairment may be due to the demands on generative semantic memory that also characterize recall of historical events or fables. However, the impoverished retrieval of semantic information in amnesic participants in Race et al. (2013) could also have been due to the fact that such retrieval in control participants was facilitated by episodic memory processes involved in the recovery of autobiographical details (e.g., recalling being in a long line at the gas station when elaborating on the impact of oil shortages on people’s lives), thus providing an alternative explanation for the impairment in amnesia.

The goal of the present study was to examine memory for well-established semantic narratives in patients with MTL amnesia. Like Rosenbaum and colleagues (Rosenbaum, et al., 2009), we turned to memory for fairy tales and bible stories because these stories are learned early in life, typically many years prior to the onset of amnesia, and their retrieval is not in any obvious way facilitated by autobiographical memory.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Eight patients with amnesia (two female) participated in the study. For each of these individuals, the neuropsychological profile indicated severe impairment limited to the domain of memory. Experimental data from one patient were excluded because she indicated low familiarity with all the stories, and as such, only the demographic and neuropsychological data for the remaining seven patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic, Neuropsychological and Neurological Characteristics

| Patients | Etiology | Age | Edu | WAIS, III

|

WMS, III

|

Hipp Vol Loss | Subhipp Vol Loss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIQ | WMI | GM | VD | AD | ||||||

| P01 | Anoxia + L Temporal Lobectomy | 48 | 16 | 86 | 92 | 49 | 53 | 52 | 63% | 60%a |

| P02 | CO Poisoning | 55 | 14 | 111 | 130 | 59 | 72 | 52 | 22% | - |

| P03 | Encephalitis | 83 | 18 | 133 | 128 | 45 | 53 | 58 | N/A | |

| P04 | Cardiac Arrest | 59 | 17 | 134 | 130 | 70 | 75 | 67 | N/A | |

| P05 | Cardiac Arrest | 62 | 16 | 110 | 99 | 62 | 68 | 61 | N/A | |

| P06 | Anoxia/Ischemia | 43 | 12 | 103 | 97 | 59 | 68 | 55 | 47% | - |

| P07 | Encephalitis | 70 | 13 | 99 | 104 | 49 | 56 | 58 | N/A | |

Note: Age = Age (years); Edu = Education (years); WAIS, III = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, III; VIQ = Verbal IQ; WMI = Working Memory Index; WMS, III = Wechsler Memory Scale, III; GM = General Memory; VD = Visual Delayed; AD = Auditory Delayed; Hipp Vol Loss = Hippocampal Volume Loss; Subhipp Vol Loss = subhippocampal Volume Loss; CO = carbon monoxide.

Volume loss in left anterior parahippocampal gyrus (i.e., entorhinal cortex, medial aspect of the temporal pole, and medial portion of perirhinal cortex.

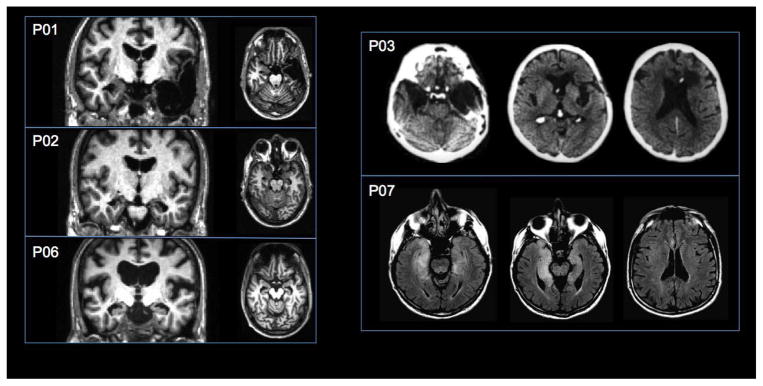

Etiology of amnesia was ischemic or anoxic event in four patients, herpes encephalitis in two patients, and status epilepticus followed by temporal lobectomy in one patient. MRI/CT scans confirmed MTL pathology for five patients. Two could not be scanned because of medical contraindications (P04 and P05). MTL pathology for these patients was inferred based on etiology and neuropsychological profile. For two patients (P01 and P03), damage extended beyond the MTL to include anterolateral temporal neocortex. For one patient (P07) MRI was acquired in the acute phase of illness and there were no visible lesions on T1-weighted images. However, T2-flair images showed bilateral hyperintensities in the MTL and anterior insula. Patients’ lesions are presented in Figure 1. As shown in Table 1, volumetric data for the hippocampus and subhippocampal cortices using methodology reported elsewhere (Kan, Giovanello, Schnyer, Makris, & Verfaellie, 2007) indicated that the lesion was restricted to the hippocampus in two patients (P02, P04).

Figure 1.

MRI and CT scans depicting lesions for five of the seven amnesic patients (see methods). The left side of the brain is displayed on the left side of the image. T1-weighted MRI images show lesion location for P01, P02, and P06 in the coronal and axial plane, CT images show lesion location for P03 in the axial plane, and T2-flair images show lesion location for P07 in the axial plane.

Twenty healthy control subjects (13 female) who were matched to the amnesic group in terms of age (mean =56.9), education (mean=15.6), WAIS-III VIQ (mean=111.7) and Working Memory Index2 (mean=107.9; all t’s <1) also participated in the study. All participants provided informed consent in accordance with the Institutional Review Boards of Boston University and the VA Boston Healthcare System.

2.2. Materials

Five fairy tales and four bible stories were selected as narratives for the present study: Little Red Riding Hood, Hansel and Gretel, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, The Three Little Pigs, Cinderella, Moses and the Exodus, Noah’s Ark, Adam and Eve, and The Nativity.

For each story, a recognition test was constructed that consisted of statements reflecting true details of the story (e.g. “The wolf arrives at the grandmother’s house before Little Red Riding Hood”) and statements incorporating two types of false details: inaccurate story details and story intrusions. Inaccurate details were story elements that were factually incorrect or described events that were the opposite of what actually happens in the story (e.g. “The wolf enters and poisons the grandmother before he eats her”). Story intrusions were details that occur in other popular narrative stories that were not part of the experiment (e.g. “Determined to reach the grandmother’s house first, the wolf gives Little Red Riding Hood an enchanted apple that makes her fall asleep for a short while”). The recognition test for each story contained between 35 and 40 statements that told the story in chronological order. The average number of true details, inaccurate details, and story intrusions varied slightly across stories to ensure that all statements presented in chronological order formed a coherent narrative. Across stories, there were on average 19.3 true statements, 8.4 false statements containing inaccurate details, and 9.9 story intrusions.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were first presented with a list of the nine stories and were asked to rate their familiarity with each story using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (vaguely familiar) to 5 (very familiar). Subjects were then asked to indicate on a separate sheet their four most familiar stories. Memory was tested for the four stories that each participant selected as having the highest familiarity, provided a minimum familiarity rating of 33. This familiarity cut-off was set to ensure that poor memory was not a result of a lack of pre-morbid familiarity with the stories.

For the recall task, participants were asked to recount each story from beginning to end, as if the experimenter had never heard the story before. They were instructed to be as descriptive as possible, including as many details as they could recall. If a participant was unable to provide any accurate information about the narrative, a predetermined cue was given (e.g. for Little Red Riding Hood, the experimenter would prompt with, “If I say ‘disguised wolf,’ can you recall anything from the story?”). Participants were allowed to continue until their story reached its natural ending. At this point, the experimenter gave a general prompt (e.g. “Can you tell me anything else that happens in the story?”). If participants were able to provide additional details, they continued with their narrative until they indicated that they had finished.

For the recognition task, each narrative was presented on a computer screen, one statement at a time in sequential order, using E-Prime software. Participants were asked to state for each sentence whether it was true or false. The title of the narrative remained on the screen throughout the presentation of statements. Before beginning the recognition task, participants completed a practice session, consisting of eight sentences that described a scene from the popular movie “The Wizard of Oz.” Half of the sentences were true and the remaining half were false and included both inaccurate details and story intrusions. Participants were asked to read each sentence out loud and to indicate whether they believed the sentence was true or false. Participants received feedback from the experimenter, and the different types of false statements were pointed out. When participants indicated that they understood the task, they continued with the test narratives. The experimenter recorded participant responses on a computer keyboard. No feedback was given during the recognition test.

Control participants completed recall and recognition for all four stories in a single session. For the amnesic patients, the task was broken up into multiple sessions to accommodate their slower pace and/or fatigue. Each session consisted of recall of one or more stories followed by recognition of the same stories.

2.4. Scoring

The narratives from the recall task were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. Narratives were scored for (1) number and type of details and (2) number and order of main steps. The narratives were scored twice, once excluding information provided following the prompt, and once including prompted information. Because the scoring methods did not affect the overall results, we report only the latter scores.

Details were scored using an adaptation of the autobiographical interview scoring procedure (Levine, Svoboda, Hay, Winocur, & Moscovitch, 2002). Each narrative was first segmented into distinct details, and each story detail was then assigned as an accurate detail, false statement, repetition, or external comment such as meta-cognitive thought. Accurate details were further assigned to one of five categories (i.e. event, perceptual/description, place, time, thought/emotion). Inter-rater reliability was calculated based on 25% of the narratives provided by patients and an equal number of narratives provided by controls. Following methods used in prior studies (Levine, et al., 2002; Race, Keane, & Verfaellie, 2011; Race, et al., 2013) the primary scorer was not blind to subject status, but the second trained scorer was blind to subject status. Inter-rater reliability was high for total number of accurate details (Cronbach’s α = 0.98) and for each type of detail (α = 0.98 for event details, α = 0.93 for perceptual/description details, α = 0.90 for place details, α = 0.89 for time details, and α = 0.96 for thought/emotion details). Likewise, there was high agreement in scoring of repetitions (α = 0.97), false details (α= 0.84), and other statements (α = 0.92).

Following on Rosenbaum et al. (2009), we also calculated the number of main thematic elements included in each participant’s narratives. This calculation was based on pilot data obtained in a group of 15 control subjects who were matched in terms of age and education to the amnesic patients. These participants were asked to list the most important elements of each story, allowing for a maximum of 10 elements for each narrative. Elements listed by 50% of the pilot subjects were considered main thematic elements. In addition to the number of thematic elements, we scored the extent to which the order in which these elements were generated adhered to the correct sequence of events, using the method of Rosenbaum et al. (2009). One point was given for each element that occurred in a position later than its appropriate position in the story, and we allowed for the possibility that there was more than one appropriate position for some elements. This score was divided by the total number of thematic elements generated (to take into account the number of incorrect orderings that were possible), with zero representing a perfect order score and higher ratios a more disordered sequence of elements. By definition, order scoring was only possible if a minimum of two thematic elements were generated.

Recognition was scored by calculating the proportion of hits and false alarms for each narrative.

3. Results

3.1. Story familiarity

The familiarity ratings of amnesic patients (median = 4.25) were numerically lower than those of controls (median = 4.75), a difference that was marginally significant (Mann-Whitney U=35, p<.06)4.

3.2. Recall

3.2.1. Recall of details

As can be seen in Table 2, amnesic patients provided fewer accurate details than controls [t(25)=3.27, p<.01)], but there were no group differences in the number of inaccurate details, repetitions, or external comments [all t’s<1, d’s<.29].

Table 2.

Mean Number (and SEM) of Accurate Details, False Details, Repetitions, and External Comments Generated by Controls and Amnesic Patients.

| Accurate | False | Repetition | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 40.18 (6.58) | 2.34 (.48) | 2.00 (.45) | 6.68 (1.13) |

| Amnesics | 16.32 (3.14) | 1.64 (.51) | 2.79 (2.22) | 7.15 (3.06) |

| MTL | 20.30 (2.50) | 1.50 (.71) | 3.50(3.13) | 8.82 (4.05) |

| MTL+ | 6.38 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

Note: MTL = patients with lesions restricted to the medial temporal lobes; MTL+ = patients with lesions extending into anterolateral temporal cortex.

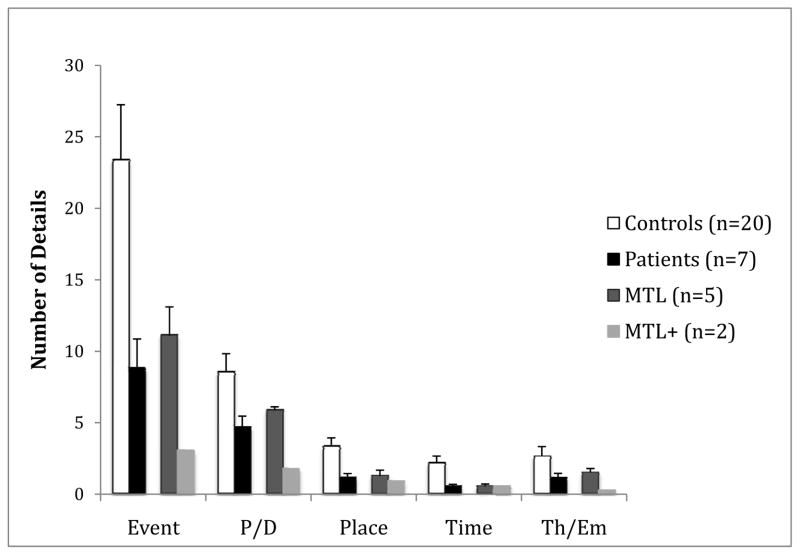

The average number of accurate details recalled, broken down by detail type, is presented in Figure 2. Because of non-homogeneity of variance, data were subjected to logarithmic transformation prior to analysis. Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used to correct for violation of sphericity. A two-way mixed factorial ANOVA with group as the between-subjects variable and type of accurate detail (event, perceptual/description, place, time, thought/emotion) as the within-subjects variable revealed a main effect of group [F(1, 25) = 4.99, p =.035, η2=.17] and a main effect of type of accurate detail [F(2.8, 70.2) = 135.74, p <. 001, η2=.65]. The group x detail type interaction was marginal [F(2.8, 70.2) = 2.21, p =.099, η2=.05].

Figure 2.

Mean number of accurate details of each type generated by controls (white bars), the whole amnesic patient group (black bars), amnesic patients with lesions restricted to the MTL (dark grey bars), and amnesic patients with lesions extending into anterolateral temporal cortex (MTL+; light grey bars). P/D = Perceptual/Description; Th/Em = Thought/Emotion. Error bars indicate SEM.

The two patients with MTL+ lesions provided the lowest number of accurate details. To evaluate whether the impairment in the amnesic group was due solely to the inclusion of the MTL+ patients, we performed an additional analysis comparing only patients with MTL lesions to controls. The main effect of group was not significant [F(1,23)=1.86, p=.19, η2=.08], but the main effect of detail type [F(3.1,70.8) = 139.22, p < .001, η2=.84] was modified by a group x detail type interaction [F(3.1,70.8) = 3.0, p =.034, η2=.02]. Post hoc comparisons indicated that the MTL patients were impaired in generating event, place, and time details [t’s>1.99, p’s<.033, one-tailed, d’s>.99], but not perceptual or thought/emotion details [t’s <1, d’s<.33]. Moreover, the two patients with volumetrically confirmed lesions limited to the hippocampus (H-only) performed as poorly as the remaining MTL patients (H-only mean total details = 17.6; H+ mean total details = 22.1).

We used correlational analyses to determine if retrieval of narrative details in the amnesic group was related to frontal executive function and/or to semantic retrieval. We calculated an executive score based on the average ranking on four measures derived from the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (number of categories and percent perseverative errors), the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (total number of appropriate responses), and Trails B (reaction time). This correlation was nonsignificant (rho=.04). The correlation between semantic fluency and retrieval of narrative details was also nonsignificant (r =.26, p=.57).

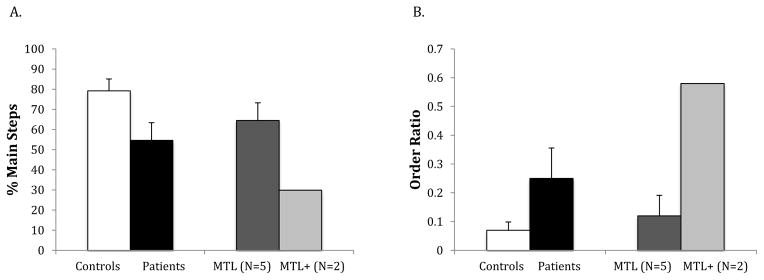

3.2.2. Recall and ordering of thematic elements

The amnesic group as a whole recalled fewer thematic elements (mean=54.6%) than did controls [mean= 79.2%; t(25) = 2.66, p=.014, d=1.06]. However, this finding was due to the performance of the MTL+ patients (see Figure 3A). The performance of the MTL patients was not significantly different from that of controls [t(23) =1.46, ns, d=.61]. Follow-up analyses using a modified t-test for single cases (Crawford & Howell, 1998) for each of the MTL patients indicated that there was no evidence for reduced recall of thematic elements in any of these patients [t’s < 1.59, p’s>.12, d’s<.73]. By contrast, each of the two MTL+ patients had lower recall of thematic elements than controls [t’s > 2.38, p’s < .01, d’s>1.09].

Figure 3.

Results for generation of main steps (A) and ordering of main steps (B) in controls (white bars), the whole amnesic group (black bars), amnesic patients with lesions restricted to the MTL (dark grey bars), and amnesic patients with lesions extending into anterolateral temporal cortex (MTL+; light grey bars).

The order score for the amnesic group was significantly higher than that for the control group [t(25) = 2.47, p =.021, d=.99], indicative of worse sequential ordering of thematic elements. This pattern was again due to the performance of the MTL+ patients (see Figure 3B). MTL patients as a group scored no differently than controls (mean = .12, t < 1, d=.32). Follow-up analyses using a modified t-test for single cases (Crawford & Howell, 1998) indicated that both MTL+ patients had higher (i.e. worse) order scores than controls [t’s > 3.03, p’s < .01, d’s>1.54]. Four of the 5 MTL patients scored no differently than controls (t’s < 1, d’s<.24), whereas one scored worse5 [t(19) = 3.19, p < .01, d=1.46].

3.3. Recognition

Preliminary analysis revealed no difference between the two types of false details, and therefore, data from these two conditions were combined for subsequent analyses. The percentage of hits and false alarms for each group is presented in Table 3. Response accuracy (hits – false alarms) was marginally lower in the amnesic group (mean = 49.5%) than in the control group [mean = 64.5%, t(25) = 1.96; p = .06, d=.78], but this effect was again due to the performance of the MTL+ patients (mean = 21.4%). MTL patients as a group performed no differently than controls (mean = 60.8%, t < 1, d=.26). Follow-up analyses using a modified t-test for single cases (Crawford & Howell, 1998) indicated that there was no evidence for impaired recognition in any of the MTL patients [t’s < 1.05, p’s > .30, d’s<.48]. However, the two MTL+ patients performed more poorly than controls [t’s > 2.37, p’s < .01, d’s>1.09].

Table 3.

Mean Proportion (and SEM) of Targets (Hits) and False Details (FAs) Endorsed by Controls and Amnesic Patients as well as Corrected Recognition Performance (Hits-FAs).

| Hits | FAs | Hits-FAs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 88.47 (1.94) | 24.00 (3.99) | 64.48 (3.58) |

| Amnesics | 86.09 (2.01) | 36.57 (8.92) | 49.52 (7.96) |

| MTL | 84.89 (2.49) | 24.12 (4.78) | 60.76 (4.32) |

| MTL + | 89.11 | 67.68 | 21.42 |

Note: FAs = False Alarms; MTL = patients with lesions restricted to the medial temporal lobes; MTL+ = patients with lesions extending into anterolateral temporal cortex.

4. Discussion

The results of this study are consistent with those of Moscovitch and Melo (1997) and Rosenbaum and colleagues (Rosenbaum, et al., 2009) in that they demonstrate that patients with amnesia are impaired in their ability to recount detailed semantic narratives. Our findings go beyond these previous studies, however, in that they elucidate the contribution of both MTL and anterolateral temporal regions to memory for semantic narratives.

Patients with lesions restricted to the MTL produced narratives that were reduced in amount of detail, but they had preserved schematic representations of the stories, as indexed by the fact that their narratives included a similar number of thematic elements as those of controls. Further, even though recall of narrative details was impoverished, recognition of such details was intact. These results suggest that lesions of the MTL do not result in loss of knowledge about premorbidly acquired semantic narratives, but rather, interfere with the ability to recover that knowledge in rich detail.

In contrast, patients with lesions extending into anterolateral temporal neocortex had a pervasive impairment in memory for semantic narratives. This impairment was apparent not only in their difficulty retrieving story details, but also in their impoverished access to schematic representations and their inability to distinguish true from false story details. These findings accord well with the notion that the anterior and lateral temporal lobes are the critical storage sites for semantic memories (Hodges, 2003; Rogers, et al., 2004; Saffran & Schwartz, 1994); Hodges, 2003; Saffran & Schwartz, 1994). Lesions affecting these regions lead to a degradation of semantic knowledge that manifests regardless of method of testing.

Despite the fact that neocortical regions are the permanent storage sites of semantic memories, it appears that they are not in themselves sufficient for all aspects of semantic memory retrieval. Our results suggest that while schematic representations can be accessed without mediation of the MTL, generative retrieval of semantic detail, even for stories acquired long before onset of amnesia, remains dependent on the MTL.

Before considering the implications of these findings, it is important to rule out a potential alternative explanation of the impairment in retrieval of semantic details in MTL amnesia. Namely, could patients’ impairment be due to compromised strategic retrieval processes mediated by the frontal lobes? Such processes are important for establishing a retrieval mode and guiding the memory search (Moscovitch & Melo, 1997). By this explanation, MTL patients’ reduced detail production might be due to incidental frontal damage leading to a disruption of executive control processes rather than to a disruption of MTL-mediated memory processes. This possibility is unlikely since none of the MTL patients had visible frontal lesions. Further, the absence of a correlation between retrieval of narrative detail and a composite executive score argues against a disruption of executive function as the cause of patients’ impoverished detail generation.

A further question concerns whether the observed impairment can be linked to a specific structure within the MTL. Both neuropsychological (Moss, Rodd, Stamatakis, Bright, & Taylor, 2005; Wang, Lazzara, Ranganath, Knight, & Yonelinas, 2010) and imaging data (Moss, Rodd, Stamatakis, Bright, & Taylor, 2005; Tyler, et al., 2013) suggest a role for perirhinal cortex in semantic processing, raising the possibility that the impairment in detail generation in the MTL group might be due to damage to perirhinal cortex. Our results argue against this explanation, as the impairment in detail generation was also evident in two patients with volumetrically confirmed damage limited to the hippocampus. Rather, our findings suggest a critical role for the hippocampus in the production of detailed semantic narratives.

The fact that memory for detailed semantic narratives acquired early in life depends on the integrity of the hippocampus reveals a striking contrast with memory for isolated semantic facts, as for the latter, the contribution of the hippocampus gradually diminishes over time until memory can be supported neocortically. A possible way to reconcile these findings is with reference to the specific demands involved in retrieval of semantic narratives. Moscovitch and Melo (1997) have suggested that memories that have a narrative structure, regardless of whether they are episodic or semantic in nature, may place special demands on the hippocampus.

Consistent with this notion, both episodic and semantic narrative memories are characterized by reduced detail in MTL patients. Yet, whereas semantic narratives are reduced in semantic detail (present study and Race et al., 2013), episodic narratives are reduced in episodic detail, but not in semantic detail (Race et al., 2011; Rosenbaum et al., 2009; Steinvorth et al., 2005). This apparent inconsistency in amnesics’ retrieval of semantic details in the context of different types of narratives likely reflects the differential demands on semantic retrieval: semantic details are not inherently necessary for the recounting of past episodic events, as evidenced by the fact that participants generate relatively few semantic details as part of their episodic narratives, whereas retrieval of semantic details is central to the recounting of semantic narratives. Thus, the two types of narrative tasks may be differentially sensitive to impairments in retrieval of semantic detail.

It is notable that the present impairment in detail generation occurred in the context of fables or bible stories that recount events. In that sense, this deficit might be seen as resembling the previously reported impairment in recounting autobiographical episodes (Race et al., 2011). In the present instance, however, the deficit is considered semantic rather than episodic because the events are not personally experienced episodes. But to the degree that one considers any sort of event, whether personally experienced or not, as episodic in nature, one might describe the present deficit as occurring within the episodic domain. However, to consider the recall of fairy tales and bible stories as episodic in nature blurs the traditionally accepted boundary between personally experienced events and semantic knowledge. Therefore, we argue that the present findings, taken together with the findings of impaired semantic retrieval in Race et al. (2013), can be best characterized as an impairment in detailed semantic retrieval.

It is important to consider MTL patients’ impairment in detailed retrieval of semantic narratives against the backdrop of their preserved performance in narrative tasks that do not require retrieval of informational elements from memory. We previously showed that MTL patients perform normally on a picture description task in which they are asked to tell a story about a visually presented scene (Race et al., 2011). One important difference between the two tasks is that the picture description task is less constrained, in the sense that there are multiple appropriate responses for describing a picture, in comparison to a single correct unfolding for a fairy tale or bible story. Additionally, the presence of a scene in the picture description task may provide a degree of external support for building up a narrative that is not present in the semantic narrative task, where information needs to be generated internally, and where it may be easier to lose track of an unfolding narrative. Although MTL patients in the present study were no more likely than controls to repeat story details in their narrative, it is nonetheless possible that their anterograde memory problems contributed to difficulty staying on track with the recounting of a semantic narrative.

There are several ways in which intact MTL function, and hippocampal functioning in particular, may be critical for the retrieval of detailed semantic narratives. One possibility is that the MTL is engaged whenever detailed associative information is retrieved, regardless of the episodic or semantic nature of a memory task (Mckenzie & Eichenbaum, 2011; Waidergoren, Segalowicz, and Gilboa, 2012). A number of neuroimaging studies have demonstrated hippocampal activation during semantic tasks that have a strong generative demand (Burianova & Grady, 2007; Burianova, McIntosh, & Grady, 2010; Maguire & Mummery, 1999; Ryan, Cox, Hayes, & Nadel, 2008; Sheldon & Moscovitch, 2012; Whitney, et al., 2009). Moreover, Waidergoren et al. (2012) have demonstrated that a generative retrieval process akin to recollection may operate intrinsically within semantic retrieval, and is not simply the result of recollection of episodic information in support of a semantic task. In the case of semantic narratives, although the schematic or gist representation may serve as the overarching framework for retrieval, it may not be sufficient in itself to elicit a multitude of story details. Rather, retrieval of one story element may serve as a retrieval cue for additional details with which it is associated, either sequentially or in terms of underlying story structure. Support for the notion that such extended associative retrieval processes may critically depend on the hippocampus comes from a recent electrophysiological study that found that hippocampal activity predicts the retrieval of semantically related information during memory search (Manning, Sperling, Sharan, Rosenberg, & Kahana, 2012), as well as from a lesion study in which patients with MTL damage showed impaired retrieval of semantic detail when associative aspects of remote semantic information were probed (Waidergoren et al., 2012).

It has been argued that aside from its role in retrieval of narrative details, the MTL may also play a critical role in binding story elements into coherent, multi-element representations. This explanation draws on the notion that the hippocampus is critical for relational processes that link together disparate pieces of information in the service of long-term memory retrieval (Cohen & Eichenbaum, 1993; Eichenbaum, Yonelinas, & Ranganath, 2007; Henke, 2010). Although more commonly associated with episodic memory, such hippocampal binding functions may also apply to semantic memory (Race, et al., 2013). Rosenbaum and colleagues (Rosenbaum, et al., 2009) suggested that the lack of detail in K.C.’s recounting of semantic narratives reflects a deficit in reconstructive processes that bind informational elements into a coherent narrative. It is not possible, however, to directly link any proposed mechanism responsible for K.C.’s deficit to the role of the hippocampus, given that K.C.’s damage is extensive, and goes beyond the MTL to include the frontal lobes.

Distinguishing between a detailed associative retrieval and a binding explanation of patients’ impoverished semantic narratives is challenging. For instance, Rosenbaum et al. (2009) favored a binding interpretation of K.C.’s impairment because K.C.’s intact ability to discriminate true from false details in a recognition task suggested that there was no loss of actual knowledge for the semantic narratives. However, this finding does not in itself rule out a retrieval interpretation, as recall of details poses demands on associative retrieval processes that recognition does not. In our own data, the lack of correlation between performance on a semantic fluency task, a task that requires associative search through semantic memory, and retrieval of details in the semantic narratives could be taken as evidence against the associative retrieval interpretation, thus adding weight to a binding interpretation. However, the production of narratives based on picture descriptions might be expected to make equal demands on hippocampal binding processes, yet MTL patients perform normally on this task (Race et al., 2011). To distinguish between these two interpretations, future studies will be needed that uncouple demands on detail generation from demands on integrated narrative construction. One way in which this might be accomplished is in the context of a fluency task that requires generation of details from a fairy tale, without the need to construct a coherent narrative.

The notion that hippocampally-mediated retrieval and/or binding processes are critical for the reconstruction of semantic narratives acquired long ago poses a challenge for both standard consolidation theory (Squire, 1992; Squire & Alvarez, 1995; Squire & Zola, 1998) and multiple trace theory (Moscovitch et al., 2006; Winocur & Moscovitch, 2011) as both postulate that the hippocampus is necessary for the maintenance and retrieval of semantic information for only a limited period of time: once consolidated, semantic memories are thought to be retrieved in their original form neocortically, without recourse to the hippocampus. The finding that MTL patients show normal recognition of narrative details suggests that detailed semantic representations are indeed stored neocortically, yet reconstruction of the memory in rich detail continues to depend on the hippocampus.

The proposal that reconstruction of detailed semantic memories, like episodic memories, continues to depend on interactions between the hippocampus and neocortex also allows for the possibility of continued hippocampal updating after consolidation is complete. In that regard, even though we avoided narratives that recently received widespread attention in popular media (e.g. film), it is nonetheless possible that participants had additional exposure to the semantic narratives in more recent years. For control participants, such re-exposure may serve to re-engage the hippocampal network that was engaged during initial learning, further strengthening the existing neocortical connections. It may also allow for the integration of additional information into the already existing neocortical representation (Kan, Alexander, & Verfaellie, 2009; Tse, et al., 2007). The disruption of this updating process in patients with MTL amnesia may have further placed them at a disadvantage.

Finally, our findings also provide novel information regarding the neural regions involved in the correct ordering of thematic elements in a semantic narrative. Patients with lesions extending into temporal neocortex, but not those with lesions limited to the MTL, had difficulty reconstructing the temporal sequence of the main elements provided in their narratives. This suggests that information about the sequential unfolding of the thematic elements of a story does not depend on the integrity of the MTL, but rather, is represented as part of a neocortically supported schematic representation. Our results in the semantic domain parallel findings in a study of autobiographical memory (St-Laurent, Moscovitch, Tau, & McAndrews, 2011): as expected, patients with MTL lesions provided reduced autobiographical details, but they had intact memory not only for the major sub-events comprising an episode, but also for their chronological order.

It is of interest to consider the performance of K.C. in the context of our findings, as K.C. demonstrated poor sequential organization. Rosenbaum and colleagues (Rosenbaum, et al., 2009) took K.C.’s difficulty as reflecting the broader role of the MTL in binding. However, the intact performance of the MTL patients in the current study calls into question this interpretation. Given that K.C.’s lesion extends into frontal cortex, a more likely possibility is that his poor ordering reflects the role of frontal regions in ordering of events and actions within a narrative (Allain, et al., 2001; Partiot, Grafman, Sadoto, Flitman, & Wild, 1995; Sirigu, et al., 1995; Zalla, Phipps, & Grafman, 2002) and/or within remote memory (Yasuno, et al., 1999). By this view, while basic order information may be part of the schematic representation, executive processes are necessary to maintain and organize this information in the context of an unfolding narrative.

Rosenbaum and colleagues (Rosenbaum, et al., 2009) interpreted K.C.’s poor temporal order as an expression of reduced narrative coherence. Our finding of intact ordering in MTL patients does not negate the possibility that MTL regions play an important role in the coherence of discourse. In addition to the sequence of thematic elements in a story, other factors such as the sequence and organization of details and the interrelatedness of utterances contribute to the overall sense of continuity in a story. Recent evidence suggests that patients with MTL lesions have reduced coherence in generating different types of discourse (Kurczek & Duff, 2011; Race, Keane, & Verfaellie, 2012), although it is not known whether this deficit extends to the recall of semantic narratives. While the present study has focused on a quantitative analysis of patients’ narratives, further studies evaluating qualitative aspects of their recall, such as global and local coherence (Glosser & Deser, 1991), will be needed to more fully understand the impact of MTL lesions on remote memory for semantic narratives.

Another question that remains for future study is whether there are strategies that might help recovery of narrative detail in patients with MTL lesions. Rudoy and colleagues (Rudoy, Weintraub, & Paller, 2009) have suggested that individuals with severe anterograde amnesia may habitually use a gist-based retrieval orientation when recalling remote memories, because their inability to remember details of recent events leads to the development of recall strategies wherein details are left out. Although it is unlikely that strategy differences alone can account for the severe impairment in detail generation observed in this study, it would nonetheless be of interest to evaluate whether induction of a detail-oriented strategy could improve the retrieval of neocortically represented semantic narratives in patients with MTL lesions.

We examined memory for well-established semantic narratives in amnesic patients

MTL patients produced narratives that had reduced detail

The number and order of main thematic elements was normal in MTL patients

Patients with MTL+ lesions were impaired on all measures

Findings are inconsistent with theories of memory consolidation

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant #R01MH093431 and the Clinical Science Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank Dr. Daniela Palombo for help with lesion analysis and Aubrey Wank for help with data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

The Working Memory Index was prorated based on Digit Span and Arithmetic performance.

As noted in the subject section, this resulted in the elimination of an amnesic patient who indicated insufficient familiarity with any of the stories. Additionally, only 3 stories met the set familiarity criterion for one control subject and 2 amnesic patients.

The marginally significant reduction in familiarity ratings was due the MTL subgroup (Mann-Whitney U=21.5, p<.06), as the patients in the MTL+ subgroup had familiarity scores in the normal range. We compared the performance of the MTL patients to that of a subset of controls who were matched in their familiarity ratings. These analyses yielded the same results as those including all control participants.

This patient’s impaired order performance was due to a very high score for one story, for which he recounted the ending at the very beginning. The other elements, however, were in correct order.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allain P, Le Gall D, Etcharry-Bouyx F, Forgeau M, Mercier P, Jean E. Influence of centrality and distinctiveness of actions on script sorting and ordering in patients with frontal lobe lesions. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2001;21:643–665. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.4.465.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burianova H, Grady CL. Common and unique neural activations in autobiographical, episodic and semantic retrieval. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19:1520–1534. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.9.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burianova H, McIntosh AR, Grady CL. A common functional brain network for autobiographical, episodic, and semantic memory retrieval. Neuroimage. 2010;49:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolotti L, Shallice T, Chan D, Fox N, Scahill R, Harrison G, et al. Long-term retrograde amnesia... the crucial role of the hippocampus. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:151–172. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Eichenbaum H. Memory, Amnesia, and the Hippocampal System. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Howell DC. Comparing an individual’s test score againt norms derived from small samples. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1998;12:482–486. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AR, Ranganath C. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2007;30:123–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T, Moscovitch M, Nadel L. Consolidation, retrograde amnesia, and the temporal lobe. In: Boller F, Grafman J, editors. The Handbook of Neuropsychology. 2. Vol. 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Glosser G, Deser T. Patterns of discourse production among neurological patients with language disorders. Brain and Language. 1991;40:67–88. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(91)90117-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke K. A model for memory systems based on processing modes rather than consciousness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nrn2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges JR. Semantic dementia: A disorder of semantic memory. In: D’Esposito M, editor. Neurological Foundations of cognitive Neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT press; 2003. pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kan IP, Alexander MP, Verfaellie M. Contribution of prior semantic knowledge to new episodic learning in amnesia. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21:938–944. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan IP, Giovanello KS, Schnyer DM, Makris N, Verfaellie M. Role of the medial temporal lobes in relational memory: Neuropsychological evidence from a cued recognition paradigm. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2589–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurczek J, Duff MC. Cohesion, coherence, and declarative memory: Discourse patterns in individuals with hippocampal amnesia. Aphasiology. 2011;25:700–712. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2010.537345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Svoboda E, Hay JF, Winocur G, Moscovitch M. Aging and autobiographical memory: dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval. Psychology and aging. 2002;17:677–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Mummery CJ. Differential modulation of a common memory retrieval network revealed by positron emission tomography. Hippocampus. 1999;9:54–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:1<54::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning JR, Sperling MR, Sharan A, Rosenberg EA, Kahana MJ. Spontaneously reactivated patterns in frontal and temporal lobe predict semantic clustering during memory search. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:8871–8878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5321-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckenzie S, Eichenbaum H. Consolidation and reconsolidation: Two lives of memories? Neuron. 2011;71:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch M, Melo B. Strategic retrieval and the frontal lobes: Evidence from confabulation and amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:1017–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch M, Nadel L, Winocur G, Gilboa A, Rosenbaum RS. The cognitive neuroscience of remote episodic, semantic and spatial memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HE, Rodd JM, Stamatakis EA, Bright P, Tyler LK. Anteromedial temporal cortex supports fine-grained differentiation among objects. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:616–627. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partiot A, Grafman J, Sadoto N, Flitman S, Wild K. Brain activation during script event processing. Neuro Report. 1995;8:3091–3096. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199602290-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race E, Keane MM, Verfaellie M. Medial temporal lobe damage causes deficits in episodic memory and episodic future thinking not attributable to deficits in narrative construction. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:10262–10269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1145-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race E, Keane MM, Verfaellie M. Medial temporal lobe contributions to the organization of memory and future thought. Paper presented at the Society for Neuroscience; New Orleans, LA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Race E, Keane MM, Verfaellie M. Loosing sight of the future: Impaired semantic prospection following medial temporal lobe lesions. Hippocampus. 2013;23:268–277. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JM, Squire LR. Retrograde amnesia for facts and events: Findings from four new cases. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:3943–3954. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03943.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TT, Lambon-Ralph MA, Garrard P, Bozeat S, McClelland JL, Hodges JR, et al. Structure and deterioration of semantic memory: A neuropsychological and computational investigation. Psychological Review. 2004;111:205–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum RS, Gilboa A, Levine B, Winocur G, Moscovitch M. Amnesia as an impairment of detail generation and binding: Evidence from personal, fictional, and semantic narratives in KC. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2181–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudoy JD, Weintraub S, Paller KA. Recall of remote episodic memories can appear deficient because of a gist-based retrieval orientation. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:938–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan LR, Cox C, Hayes SM, Nadel L. Hippocampal activation during episodic and semantic memory retrieval: Comparing category production and category cued recall. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2109–2121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffran EM, Schwartz MF. Of cabbages and things: Semantic memory from a neuropsychological perspective—a tutorial review. In: Umilta C, Moscovitch M, editors. Attention and Performance XV: Conscious and Nonconscious Information Processing. Cambridge, MA: MIT press; 1994. pp. 507–536. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon N, Moscovitch M. The nature and time-course of medial temporal lobe contributions to semantic retrieval: An fMRI study on verbal fluency. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1451–1466. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirigu A, Zalla T, Pillon B, Grafman J, Agid Y, Dubois B. Selective impairments in managerial knowledge following prefrontal cortex damage. Cortex. 1995;31:301–316. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR. Memory and the hippocampus: A synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys and humans. Psychological Review. 1992:195–231. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Alvarez P. Retrograde amnesia and memory consolidation: a neurobiological perspective. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1995;5:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Bayley PJ. The neuroscience of remote memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2007;17:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola SM. Episodic memory, semantic memory and amnesia. Hippocampus. 1998;8:205–211. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:3<205::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinvorth S, Levine B, Corkin S. Medial temporal lobe structures are needed to re-experience remote autobiographical memories: Evidence from H.M. and W.R. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:479–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Laurent M, Moscovitch M, Tau M, McAndrews MP. The temporal unraveling of autobiographical memory narratives in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy or excisions. Hippocampus. 2011;21:409–421. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler LK, Chiu S, Zhuang J, Randall B, Devererux BJ, Wright P, et al. Objects and categories: Feature statistics and object processing in the ventral stream. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;25:1723–1735. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse D, Langston RF, Kakeyama M, Bethus I, Spooner PA, Wood ER, et al. Schemas and memory consolidation. Science. 2007;316:76–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1135935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waidergoren S, Segalowicz J, Gilboa A. Semantic memory recognition is supported by intrinsic recollection-like processes: “The butcher on the bus” revisited. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:3573–3587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WC, Lazzara MM, Ranganath C, Knight RG, Yonelinas AP. The medial temporal lobe supports conceptual implicit memory. Neuron. 2010;68:835–842. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmacott R, Black SE, Freedman M, Moscovitch M. The contribution of autobiograhical significance to semantic memory: Evidence from Alzheimer’s disease, semantic dementia, and amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:25–48. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney C, Weis S, Krings T, Huber W, Grossman M, Kircher T. Task-dependent modulations of prefrontal and hippocampal activity during intrinsic word production. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21:697–712. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winocur G, Moscovitch M. Memory transformation and systems consolidation. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2011;17:766–780. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuno F, Hirata M, Takimoto H, Taniguchi M, Nakagawa Y, Ikejiri Y, et al. Retrograde temporal order amnesia resulting from damage to the fornix. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1999;67:102–105. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.1.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalla T, Phipps M, Grafman J. Story processing in patients with damage to the prefrontal cortex. Cortex. 2002;38:215–231. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]