Abstract

Purpose

To update and extend prior work reviewing websites that discuss home drug testing for parents and assess the quality of information that the websites provide to assist them to decide when and how to use home drug testing.

Methods

We conducted a world-wide web search that identified eight websites providing information for parents on home drug testing. We assessed the information on the sites using checklist developed with field experts in adolescent substance abuse and psychosocial interventions that focus on urine testing.

Results

None of the websites covered all of items on the 24-item checklist, and only three covered at least half of the items (12, 14, and 21 items, respectively). The five remaining websites covered less than half the checklist items. The mean number of items covered by the websites was 11.

Conclusions

Among the websites that we reviewed, few provided thorough information to parents regarding empirically-supported strategies to effectively use drug testing to intervene on adolescent substance use. Furthermore, most websites did not provide thorough information regarding the risks and benefits to inform parents’ decision to use home drug testing. Empirical evidence regarding efficacy, benefits, risks, and limitations of home drug testing is needed.

Keywords: Home drug testing, adolescents, parents, substance abuse, substance dependence

Introduction

In 1997, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first home drug testing kit to be available without a prescription, and, within the following year, more than 200 products were approved for home drug testing. Since then, many for-profit companies have made these products commercially available for online purchase. Additionally, concerned parents have developed their own websites providing information and advice in an effort to help other parents prevent or address their child’s drug and alcohol use (Levy et al., 2004). Parents seek advice from a variety of sources, including the Internet, regarding adolescent substance use; however, information on these websites is not necessarily empirically supported (Levy et al., 2004; Schwartz et al., 2003). Given that the commercial industries that sell home drug testing products do not report their sales data, it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of home testing product purchased by parents (Moore & Haggerty, 2001). However, in 2011 over 1.7 million adolescents between the ages of 12–17 in the U.S. were estimated to have a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) with 1.1 million meeting criteria for dependence or abuse on illicit or prescription drugs, 900,000 for alcohol dependence or abuse, and 380,000 for both (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011), suggesting that there is a large potential market for the use of home testing products.

Parental monitoring has been associated with less use of alcohol and drugs (Clark, Shamblen, Ringwalt, & Hanley, 2012; Kaynak et al., 2013). Although these studies defined monitoring as keeping track of children’s friends, whereabouts, activities, and social plans, the potential for using home drug tests for more direct parental monitoring of substance use is apparent. However, empirical evidence specific to the benefits of parental monitoring through home drug testing has not been directly established, and health professionals stress safety concerns, including the technical limitations of testing, failure to correctly administer and use testing kits, false-positive and false-negative test results, and inaccurate interpretations of the results (Arcinegas-Rodriguez et al., 2011; Casavant, 2002; American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Davidson, 2009; Levy et al., 2004; Levy et al., 2006a & 2006b; Moore & Haggerty, 2001). In addition, health professionals have cautioned parents to be aware of potential unintended psychosocial and behavioral consequences from parent-administered home drug testing. These include increases in conflict and violence and other disruptions to the relationship between parents and their children due to violating the children’s rights and trust (Arcinegas-Rodriguez et al., 2011; AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Levy et al., 2004), children switching to heavy drinking and new or synthetic drugs that might not be included in the home drug test panel or be harder or impossible to detect by home drug testing (AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Heyman & Adger, 1996; Levy et al., 2004; Levy et al., 2006b; Levy et al., 2007), increasing drug use right after home drug testing as children assume that parents will not test them again, parents’ following unsubstantiated claims and advice, and delayed diagnosis and treatment of potentially serious substance use or psychiatric disorders (AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Heyman & Adger, 1996; Levy et al., 2004). These concerns have led the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007) and other professional organizations to recommend against parental home drug testing without professional guidance and likely have contributed to adamant resistance to home drug testing among some professionals.

Levy et al. (2004) recommended against home drug testing by parents after conducting a world-wide web search in 2001 to closely examine the contents of websites that specifically advertised drug testing products to parents. The study identified eight websites that sold home drug testing kits and had a specific section for parents. All of them listed multiple reasons why parents should perform home drug testing; for example, to support children in resisting peer pressure and give parents the evidence of their children’s substance use. Content covered by the reviewed websites included educational materials for interested readers, information on the role of parents in preventing adolescent substance use, news stories related to adolescent substance use, recommendations for developing a family drug and alcohol policy such as repeated random testing, obtaining a child’s assent before performing a test, and what to do if their child admits to drug or alcohol use. Five of the eight websites included direct links to other websites for substance abuse-related support groups and government and nonprofit organizations. No website provided detailed instructions for collecting a valid specimen according to the protocol recommended by National Institutes on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 2009); three recommended confirmatory testing for positive urine tests conducted by parents; one provided technical assistance for testing urine samples; and four suggested that parents seek professional help if their child tested positive for drugs. Although some of the drug-related information presented on these websites might be useful, Levy et al. (2004) concluded that parents would be better served by referral to professionals for an assessment of their child’s suspected substance use.

Although there have been no well-controlled trials evaluating home drug testing conducted independently by parents, providing rewards and consequences contingent on biochemical drug testing results, confirmed by professional testing laboratories, has often been successfully implemented in clinical research (Dutra et al., 2008; Griffith et al., 2000; Lussier et al., 2006) and shows very good efficacy in treating outpatients with substance use disorders (Castells et al., 2009). This approach has also been efficacious and safe when combined with parent training to monitor their children’s substance misuse and provide contingent rewards and consequences (Donohue et al., 2009; Stanger et al., 2009). The parent training in these studies has included weekly in-person counseling sessions for 3–4 months, covering topics on identifying and labeling adolescent behavior, developing contingency plans, and building limit-setting, monitoring, and relationship skills (Stanger et al., 2009).

Taking procedural information from empirically-supported urine monitoring interventions implemented by professionals and parents, we conducted a website review examining the comprehensiveness of the information provided for parents to (1) do home drug testing using procedures similar to those that have empirical support; (2) evaluate risks and benefits of the procedure; and (3) take appropriate precautions to reduce risks. Our purpose was not only to examine the extent to which websites provided this information for parents 10 years after the Levy et al. (2004) review, but also to extensively examine psychosocial contents of reviewed websites with an empirically-based checklist.

Method

Checklist Items for Website Review

We developed an initial checklist based on the biological testing section of a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 2009) drug use screening manual; manuals of empirically-supported contingency management and parental training interventions that focus on urine monitoring; and literature describing clinicians’ concerns regarding home drug testing by parents (Arcinegas-Rodriguez et al., 2011; Casavant, 2002; AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Heyman & Adger, 1996; Levy et al., 2004; Levy et al., 2006a & 2006b; Levy et al., 2007; Moore & Haggerty, 2001). We then requested feedback on the checklist from a panel of five external experts (see acknowledgement) that included two of the authors of the earlier review (Levy et al., 2004) and other established scientists and clinicians in the field of substance abuse covering, pediatrics, adolescent medicine, and adolescent psychosocial substance abuse treatment. Based on their comments, we elaborated on the existing content, and added four more checklist items. The final checklist (Table 1) contained a total of 24 items in three categories: assessing appropriateness for home drug testing and preparing for it (e.g., who is appropriate to test or be tested, potential for positive and negative effects, how to introduce the testing); how to conduct home testing (e.g., how to initiate a test, verify that the urine is their child’s, interpret results, deliver consequences); and provision of additional information and resources (e.g., technical support, counseling support, treatment options). The revised checklist was again circulated and received final agreement from the field experts.

Table 1.

| Website | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items for Assessing and Preparing for Home Drug Testing | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Total # of websites |

|

| 1 | Helps parents identify an adult who would be appropriate to implement home drug testing | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 2 | Tells parents how to evaluate whether their child is an appropriate candidate for home testing | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| 3 | Explicitly warns parents that home drug testing their child may lead the child to switch to use different or untestable substances (e.g., bath salts, synthetic marijuana) | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 4 | States potential benefits of home drug testing for their child | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 |

| 5 | Discuss empirical support or lack thereof for warnings and potential benefits | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | X | 2 |

| 6 | Instructs parents how to introduce the idea of and reason for home drug testing | X | X | X | X | - | - | - | X | 5 |

| 7 | Instructs parents to receive assent from their children before performing a test | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Items Directly Relevant to Home Drug Testing | ||||||||||

| 8 | Instructs parents to establish a drug and alcohol policy with regard to testing (e.g., repeated random testing) | X | X | - | X | X | X | - | X | 6 |

| 9 | Tells parents how to set consequences with their child with the testing result | X | X | - | X | - | X | - | - | 4 |

| 10 | Instructs parents how to initiate urine testing for that day | X | - | - | - | X | - | - | - | 2 |

| 11 | Instructs parents how to verify that the urine is their child’s | X | - | X | X | X | - | X | X | 6 |

| 12 | Instructs parents how to use the testing kit after urine collection | X | X | X | - | X | - | - | - | 4 |

| 13 | Instructs parents how to interpret the test result correctly | X | X | X | - | X | - | - | - | 4 |

| 14 | Warns testers to have professional back-up on interpreting the results in case of negative consequences contingent on or reactions to positive results | X | - | X | - | X | X | - | - | 4 |

| 15 | Cautions parents on the conceptual and technical limitations of drug screening kits | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 |

| 16 | Instructs parents what to do and what not to do with the testing result | X | X | X | X | - | X | - | - | 5 |

| 17 | Instructs parents what to say and what not to say with the testing result | - | - | X | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Items that Offer Additional Information to Home Drug Testing | ||||||||||

| 18 | Offers professional technical support (either by themselves or referral) for parents | X | X | X | - | X | X | - | - | 5 |

| 19 | Offers professional counseling support (either by themselves or referral) for parents | - | X | X | X | - | - | X | - | 4 |

| 20 | Offers a list of treatment referrals in case of positive results | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | 7 |

| 21 | Provides information about types of treatment | X | - | - | X | - | X | X | - | 4 |

| 22 | Instructs parents how to fade or intensify testing frequency | - | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 23 | Instructs parents when to fade or intensify testing frequency | X | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 |

| 24 | Instructs parents how to suggest treatment to their child | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Total # of checklist items | 21 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 6 | ||

Website Selection

The authors employed comprehensive web-search strategies described by Levy et al. (2004) and Schmidt and Ernst (2004), selecting the most commonly used search engines (Google®, Yahoo®, and Bing®) and a meta-search engine (WebCrawler®) to yield the maximum number of commonly visited websites. We used four search terms (“parent”, “drug test”, “home”, and “kit”) connected by the Boolean operator (“AND”).

We reviewed the first 50 websites returned by each search engine. Focusing on the first 50 websites replicates the method from prior work by Levy et al. (2004), and is a frequently-used approach that restricts the review to sites most likely accessed, given that 90% of search engine users do not look at search results beyond the first page (Freeman & Chapman, 2012). For our review, we included websites that (1) were returned in at least two search engines; (2) discussed home drug testing products whether or not they were directly available for sale on that website; and (3) addressed parents as potential consumers. Websites met the second criterion if a website introduced home drug testing products, whether by non-profit websites developed by concerned parents and by for-profit websites that offered products. Websites met the third criterion if they included words or phrases such as “parent”, “your child”, “your teen”, and “your kid”. We excluded websites that advertised products that required sending test samples to a laboratory for analysis and did not allow parents to determine the results at home (e.g., hair samples). The websites were reviewed online and printed in their entirety between June and July 2012. Each site was reviewed independently by two of the authors (Fairfax-Columbo and Ball) to determine if the site met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Discrepancies in decision of which website to include or exclude between the two authors were discussed with two investigators (Washio and Kirby) and resolved by reviewing the inclusion and exclusion criteria, then coming to an agreement on whether to include or exclude a website for review. Examples include determining whether the page was directed toward parents and excluding websites with only an option of hair sample testing. The decisions were then incorporated to clarify inclusion and exclusion criteria as needed.

Evaluation of the Selected Websites

Each site was also reviewed independently by the same two of authors using the checklist to evaluate the type of information given to parents. Both authors checked correspondence between the content in each website and checklist items to code the type of information provided. We did not include information listed in blogs associated with the websites because the information in the blog was not provided by the website owner but by readers.

The authors compared their checklists with each other. When the authors did not agree on the part corresponding to a checklist item within a website or when only one of them identified or did not identify a part corresponding to a checklist item, the website was reviewed by two investigators (Washio and Kirby), and the discrepancies were discussed and resolved. These decisions were then used to clarify criteria for the checklist items. The evaluation was replicated in August 2012 by another author (Cassey) who was not involved in the initial evaluation to again verify results and look for any updates on these websites. No significant changes in the content of the websites were noted.

Results

Sixty of 200 websites across four search engines introduced home drug testing products. Eight of the 60 websites came up in more than two search engines and listed information specifically targeting parents. Although the search returned the same number of websites as Levy et al., (2004), none of the website addresses (i.e., URL) overlapped with the previous review. Three of the websites from Levy et al. (2004) had been terminated, four did not appear within the first 50 sites returned in our search, and one did not meet our inclusion criterion (i.e., hair testing by professional laboratories).

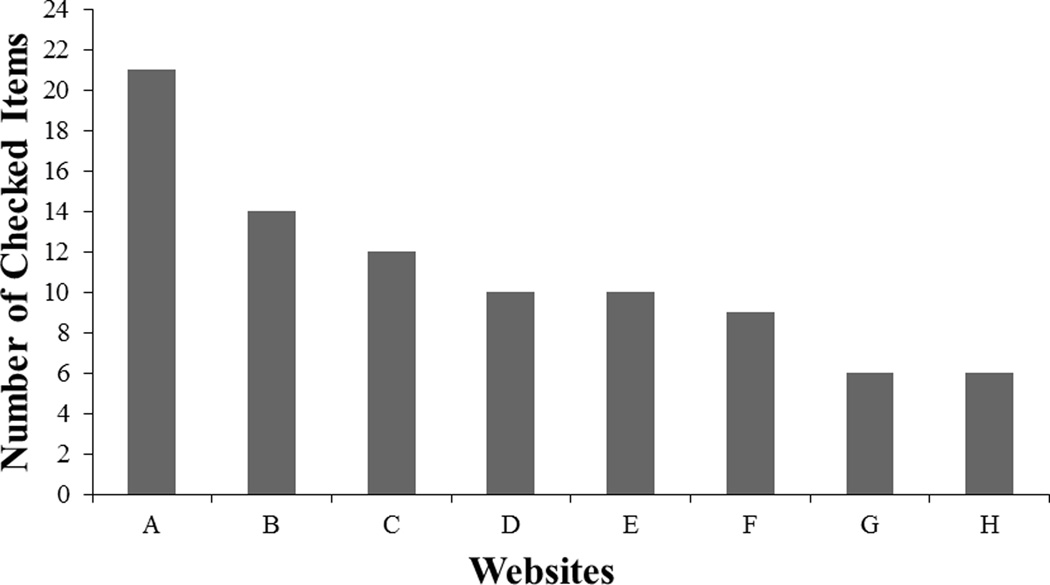

We found that none of the websites covered all of items on the checklist, and only three covered at least half the number of items on the checklist (12, 14, and 21 items, respectively; see Figure 1). The five remaining websites covered less than half the checklist items, with the number of items covered ranging from 6 to 10 items. Overall, the mean number of items covered across all eight websites was 11.

Figure 1.

The number of checked items on the checklist in each website. The checklist has a total of 24 items.

The total number of websites that covered each checklist item is presented in Table 1 (see last column). Eight items were covered by more than half the reviewed websites (i.e., on 5 or more websites). It is worth noting that the checklist items “States potential benefits of home drug testing for their child” and “Cautions parents on the conceptual and technical limitations of drug screening kits” were covered by all the reviewed websites. Although all the websites included cautions, the amount of information provided in each website varied.

Discussion

We found that the number of websites discussing home drug testing for parents and meeting our inclusion criteria was low (N = 8) and had not increased in number relative to the earlier review a decade ago (Levy et al., 2004). Unfortunately, as was the case a decade ago, most of the websites lacked content consistent with professional guidelines and evidence-based procedures considered important by relevant field experts. As such, most websites did not provide parents with enough information to allow them to be well-informed in considering if and when to use home drug testing or how to use it to achieve optimal benefits. Not all safety concerns emphasized by substance use professionals (described in the introduction) were addressed by the reviewed websites, especially regarding: a) potential increase in disruptions to the relationship between parents and their children due to violating the children’s rights and trust (Arcinegas-Rodriguez et al., 2011; AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Levy et al., 2004; Checklist Items# 1, 2, 7, 10, and 17); b) children switching to heavy drinking and new or synthetic drugs that might not be included in the home drug test panel or be harder or impossible to detect by home drug testing (AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Heyman & Adger, 1996; Levy et al., 2004; Levy et al., 2006b; Levy et al., 2007; Checklist Items# 3 and 5); c) increasing drug use right after home drug testing as children assume that parents will not test them again, and d) failure to make adequate treatment referral (AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007; Heyman & Adger, 1996; Levy et al., 2004; Checklist Items# 22, 23, and 24).

Anecdotally, we noted that information was often presented in an unsystematic way, making it difficult for parents to determine when they had reviewed all of the important information regarding home drug testing. For example, information frequently was provided on different pages within the website, with no central location summarizing the information or providing links to the other pages. The only exception was Website H, which listed information relevant to the checklist items in one parent-related webpage. Future websites should present information in a more systematic and visible manner.

Parents are potentially major consumers of home drug testing products and should be provided with professionally informed guidelines, such as those listed in the checklist, to maximize the potential benefits of home drug testing. The information should also indicate when and why parents should seek additional professional support for home drug testing and the type of potential support to seek and expect. Extrapolating from empirically-supported adolescent treatments, the professional support ideally would at least provide parents with support in communication skills, dealing with drug-positive urine tests, and praising or providing other rewards for drug-negative tests (cf. Kirby et al., 1999; Moos, 2007; Stanger et al., 2009; Waldron & Turner, 2008). Because research suggests that new intervention skills are less likely to be acquired from information alone than when coaching and feedback from a skilled professional is involved (cf. Manual et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2004), parents’ skills in home drug testing will most likely improve under the guidance of behavioral health professionals, and information on websites should be seen as supplemental to these sources. However, parents should understand that this type of ideal training is not widely available and that few professionals have experiences assisting with home drug testing. As such, they may be more likely to find a professional that will work with them but insist on laboratory testing. Furthermore, parents should be prepared to encounter professionals that strongly advise against home testing or laboratory testing. In fact, in addition to expressing concerns about safety, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2007) states that more empirical research is promptly needed to examine benefits, risks, and limitations of home drug testing. Lack of empirical evidence might also be one of the leading contributors to lack of knowledge, training, and, thus, practice regarding drug testing not only for parents but also for medical professionals. Finally, empirical evidence regarding well-defined protocols may also help medical professionals make proper referrals to behavioral and mental health professionals upon identifying drug-positive results, instead of dealing with the positive results in their office (Levy et al., 2006a & 2006b).

We used the same search terms and procedures that Levy et al. (2004) used for the purposes of updating and expanding their review and for exploring the extent to which website information may have changed over the past decade. Future reviews might expand or revise the search terms and ranges to capture a wider variety of websites discussing home drug testing.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we suggest that websites could be improved by including more information derived from biological testing guidelines; manuals of empirically-supported contingency management and parental training interventions that focus on urine monitoring; and literature describing clinicians’ concerns regarding home drug testing by parents. This information could better assist parents to more effectively consider when and how to use home drug testing. Empirical research directly examining efficacy, benefits, risks, and limitations in home drug testing is needed to better inform the development of professionally-approved guidelines for using home testing products. Guidelines then could be provided by websites in a systematic and reader-friendly manner. In addition to including instructions and recommendations for parents, websites ideally would also include a list of professionals and other resources available to directly help parents to use the products effectively and avoid potentially harmful consequences.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Kathleen Myers, Catherine Stanger, Sharon Levy, John Knight, and Mark J. Fishman for reviewing this manuscript and providing feedback regarding the checklist examining webpage content.

Funding Source: This study was supported by an NIH grant, 5P50DA027841.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributors’ Statement

Yukiko Washio: Dr. Washio conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the review, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Jaymes Fairfax-Columbo: Mr. Fairfax-Columbo helped review the literature, develop the checklist, and review and evaluate the websites.

Emily Ball: Ms. Ball helped develop the checklist and review and evaluate the websites.

Heather Cassey: Ms. Cassey helped review the literature and provided a secondary evaluation of the websites.

Amelia M. Arria: Dr. Arria assisted in re-conceptualizing and revising the manuscript.

Elena Bresani: Ms. Bresani helped develop the checklist and revise the manuscript.

Brenda Curtis: Dr. Curtis helped re-conceptualize and revise the manuscript.

Kimberly C. Kirby: Dr. Kirby participated in conceptualizing and designing the study, finalizing the checklist and evaluation procedures, and in revising the manuscript.

References

- Arcinegas-Rodriguez S, Gaspers MG, Lowe MC., Jr Metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia, and severe myalgias: An attempt to mask urine drug screen results. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2011;27(4):315–317. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182131592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AC, DiGuiseppi G, Laudet A, Rosenwasser B, Knoblach D, Carpenedo CM, Kirby KC. Developing an evidence-based, multimedia group counseling curriculum toolkit. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;43(2):178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casavant MJ. Urine drug screening in adolescents. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2002;49(2):317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(01)00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells X, Kosten TR, Capella D, Vidal X, Colom J, Casas M. Efficacy of opiate maintenance therapy and adjunctive interventions for opioid dependence with comorbid cocaine use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(5):339–349. doi: 10.1080/00952990903108215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HK, Shamblen SR, Ringwalt CL, Hanley S. Predicting high risk adolescents' substance use over time: The role of parental monitoring. The. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2012;33(2–3):67–77. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0266-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Substance Abuse (American Academy of Pediatrics; AAP), Council on School Health (AAP) Knight JR, Mears CJ. Testing for drugs of abuse in children and adolescents: Addendum - testing in schools and at home. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):627–630. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson H. When it happens in a family: Aiding parents of substance-abusing adolescents. Family Court Review. 2009;47(2):253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue B, Azrin N, Allen DN, Romero V, Hill HH, Tracy K, Van Hasselt VB. Family behavior therapy for substance abuse and other associated problems: A review of its intervention components and applicability. Behavior Modification. 2009;33(5):495–519. doi: 10.1177/0145445509340019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden S, Leyro T, Powers M, Otto M. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B, Chapman S. Measuring interactivity on tobacco control websites. Journal of Health Communication. 2012;17(7):857–865. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.650827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, Simpson DD. Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: A meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58(1):55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RB, Adger H., Jr Testing for drugs of abuse in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1996;98(2):305–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaynak O, Meyers K, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Winters KC, Arria AM. Relationships among parental monitoring and sensation seeking on the development of substance use disorder among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(1):1457–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KC, Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Garvey KA, La Monaca V. Community reinforcement training for family and significant others of drug abusers: A unilateral intervention to increase treatment entry of drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56(1):85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Harris SK, Sherritt L, Angulo M, Knight JR. Drug testing of adolescents in general medical clinics, in school and at home: Physician attitudes and practices. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006a;38(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Harris SK, Sherritt L, Angulo M, Knight JR. Drug testing of adolescents in ambulatory medicine. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006b;160(2):146–150. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Sherritt L, Vaughan BL, Germak M, Knight JR. Results of random drug testing in an adolescent substance abuse program. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):843–848. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Van Hook S, Knight J. A review of Internet-based home drug-testing products for parents. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):720–726. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel JK, Austin JL, Miller WR, McCrady BS, Tonigan JS, Meyers RJ, Smith JE, Bogenschutz MP. Community reinforcement and family training: A pilot comparison of group and self-directed delivery. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;43(1):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore D, Haggerty K. Bring it on home: Drug testing and the relocation of the war on drugs. Social and Legal Studies. 2001;10(3):377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Theory-based active ingredients of effective treatments for substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(2–3):109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Accessed July 25, 2013];Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/resource-guide/biological-specimen-testing.

- Stanger C, Budney AJ, Kamon JL, Thostensen J. A randomized trial of contingency management for adolescent marijuana abuse and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105(3):240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K, Ernst E. Assessing websites on complementary and alternative medicine for cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2004;15(5):733–742. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RH, Silber TJ, Heyman RB, Sheridan MJ, Estabrook DM. Urine testing for drugs of abuse: A survey of suburban parent-adolescent dyads. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157(2):158–161. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Turner CW. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):238–261. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Website. [Accessed October 15, 2012];2011 Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2011SummNatFindDetTables/NSDUH-DetTabsPDFWHTML2011/2k11DetailedTabs/Web/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsTOC2011.htm.