Abstract

The Janani Suraksha Yojana, India’s “safe motherhood program,” is a conditional cash transfer to encourage women to give birth in health facilities. Despite the program’s apparent success in increasing facility-based births, quantitative evaluations have not found corresponding improvements in health outcomes. This study analyses original qualitative data collected between January, 2012 and November, 2013 in a rural district in Uttar Pradesh to address the question of why the program has not improved health outcomes. It finds that health service providers are focused on capturing economic rents associated with the program, and provide an extremely poor quality care. Further, the program does not ultimately provide beneficiaries a large net monetary transfer at the time of birth. Based on a detailed accounting of the monetary costs of hospital and home deliveries, this study finds that the value of the transfer to beneficiaries is small due to costs associated with hospital births. Finally, this study also documents important emotional and psychological costs to women of delivering in the hospital. These findings suggest the need for a substantial rethinking of the program, paying careful attention to incentivizing health outcomes.

Keywords: India, maternal health, infant health, childbirth, health policy, conditional cash transfer, qualitative research

Introduction

Despite its recent economic development, India faces important challenges to improving maternal and infant health (Bhutta et al., 2004; Claeson et al., 2000). India’s vital registration system found that the national maternal mortality rate was 178 deaths per 100,000 births in 2010–2012, and 292 in Uttar Pradesh, the country’s most populous state, and the state in which the field work for this study was carried out (Office of the Registrar General, 2013). Neonatal mortality is also very high: 35 per 1000 live births nationally in 2008, and 50 per 1000 live births in Uttar Pradesh in 2011 (Annual Health Survey, 2011).

In order to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality, the Indian government introduced the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), a “safe motherhood program,” in 2005. JSY provides cash transfers to women who give birth in government and accredited private health facilities rather than at home, and in some circumstances, payments to village health workers to accompany pregnant women to health facilities for delivery. In 2009–2010, according to administrative data compiled by Accountability Initiative, 2012, India’s JSY program cost about $300 million that year, and had over 10 million beneficiaries, making it the largest conditional cash transfer in the world by number of beneficiaries (Lim et al., 2010). The Government of India allocated 11 percent of the budget of the National Rural Health Mission, an initiative of rural health sector reform, to JSY.

JSY’s strategy of encouraging hospital births takes a different approach than previous efforts from India to make home birth safer, such as training birth attendants and promoting good neonatal care practices (Stephens, 1992; Kumar et al., 2008). JSY is part of a larger group of recent programs in South Asia that subsidize hospital deliveries, including a voucher scheme in Bangladesh (Ahmed and Khan, 2011; Nguyen et al., 2012) and the Safe Delivery Incentive Program in Nepal (Ensor et al., 2009; Witter et al., 2011; Powell-Jackson and Hanson, 2012). A related program is Rwanda’s “Pay for Performance,” in which health centers were paid by the visit and service. Basinga et al., 2011 found that this program increased hospital deliveries without improving some aspects of quality of care, such as prenatal visits.

Surveys have found high rates of participation in JSY (UNFPA, 2008; Khan et al., 2010; Sidney et al., 2012) and there are now several quantitative impact evaluations of the program. These studies find that JSY increases hospital delivery but does not improve health outcomes. Dongre, 2010 finds that finds that Indian states that got higher intensity JSY programs improved rates of hospital delivery faster than states that got lower intensity programs. Mazumder et al., 2011 find that JSY has failed to improve neonatal mortality. Lim et al., 2010 use three identification strategies to look for an effect of JSY on neonatal mortality. The first two strategies, a matching analysis and a “with-versus-without” analysis, are methodologically weak because they fail to account for selection of women into the program. The third strategy is a district level difference-in-differences analysis which compares the change in neonatal mortality in districts that got JSY with the change in neonatal mortality in districts that did not get the program. This strategy is methodologically strongest, and does not find an effect of JSY on neonatal mortality. Lim et al., 2010 also use this strategy to look for an effect of JSY on maternal mortality and do not find one.

Qualitative studies are needed to understand the puzzle of why JSY increases hospital births without improving health outcomes. The few qualitative studies that exist are implementation studies that focus on the administrative details of the program (Malini et al., 2008 and Scott and Shanker, 2010). The main contributions of this study are to address the question of why JSY does not improve health outcomes, and to provide a clear picture of the value of the program to beneficiaries. The findings suggest that JSY does not improve maternal and infant health because the program does nothing to restructure the incentives of service providers in a dysfunctional health system (see Das & Hammer, 2007 & Banerjee et al., 2008). Service providers are focused on capturing the economic rents from JSY, and provide an extremely poor quality of care.

Even if the conditionality of a cash transfer program does not improve outcomes, it might still be worthwhile if it transfers money to families in poverty in a time of need. For instance, Case, 2002 describes the South African pension, a relatively large unconditional transfer that is used by families to invest in health improvements. This paper, which provides a detailed accounting of the costs of home and hospital births, finds that the value of JSY transfers to beneficiaries is small. It also finds that women who deliver at the hospital have emotionally and psychologically taxing experiences that should be included when considering the value of the program.

Setting & context

JSY uses pre-program rates of institutional delivery to distinguish between “low-performing” and “high-performing” states, and considers Uttar Pradesh, the state where this study took place, to be “low-performing.” JSY transfers to beneficiaries are higher in low-performing states than high-performing ones, and, other than delivery in an approved institution, there are no eligibility requirements (see Dongre, 2010 for more details). Although at the national level, the program allows women who deliver in accredited private facilities to receive JSY transfers; in Uttar Pradesh, JSY transfers are only made to women who deliver in public facilities (Khan et al., 2010). The program does not make transfers for women who deliver at home.

Three villages from a poor, populous, rural district in Uttar Pradesh were studied as a part of this project.1 The district has high early life mortality; neonatal mortality was almost 15% higher than the Uttar Pradesh average in 2011 (Annual Health Survey, 2011). The villages were selected from three Gram Panchayats (local government administrative units) for their caste and class diversity. All are located within 10 kilometers of the district capital town. Only one of the villages has any households with electricity, and many families live in houses made of mud and cow dung rather than bricks and cement. The choice to study only three villages was made in order to permit the researcher to make repeated visits to the same participants. This longitudinal approach increased the depth of information gathered by allowing the author to gain access to, and the trust of, pregnant and recently delivered women, a group who, in rural Uttar Pradesh, is often sheltered from outsiders.

The villages chosen for the study are arguably among the places where JSY is most likely to affect the fraction of deliveries that take place in health facilities. The fraction of facility-based deliveries in the district before JSY was implemented was quite low; the District Level Health Survey (DLHS) 2002 indicates that less than 20 percent of women who gave birth in the district between 2001 and 2002 did so in a health facility, and the DLHS 2008, which was done as the JSY program was being launched in the district, found that 21.4 percent of last births since 2004 took place in a health facility. These figures indicate the large potential for behavior change in response to JSY.2

Birth histories suggest that JSY had an effect on the delivery location of the 20 women who participated in the study; details about the participants are given below. Most of the women in the study had given birth or been pregnant prior to their most recent birth. Only 27% of their prior births took place in a health facility rather than at home. Of births that took place before 2008, the year that ASHAs were assigned to the three villages and the de facto start of JSY in those villages, only 13% took place at the hospital. Table 1 shows that in contrast to the high rates of home birth prior to JSY, only three of the 20 births studied for this project in 2012 took place at home.

Table 1.

Characteristics of and number of interviews with pregnant and recently delivered women

| village ID | woman ID | number of interviews | birth order of studied birth | location of studied birth | prior home births | prior hospital births | age | years of education | caste | economic status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 8 | 4 | hospital | 1 | 2 | 32 | 0 | lower | poor |

| 1 | 2 | 7 | 3 | hospital | 1 | 1 | 24 | 10 | higher | less poor |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | hospital | 0 | 1 | 24 | 10 | higher | less poor |

| 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | hospital | 4 | 0 | 19 | 0 | lower | poor |

| 1 | 5 | 6 | 2 | hospital | 0 | 1 | 18 | 0 | lower | poor |

| 2 | 6 | 8 | 3 | home | 1 | 1 | 24 | 8 | higher | less poor |

| 2 | 7 | 8 | 2 | home | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | higher | poor |

| 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 | hospital | 3 | 0 | 25 | 0 | lower | poor |

| 2 | 9 | 7 | 8 | home | 7 | 0 | 33 | 0 | lower | poor |

| 2 | 10 | 6 | 2 | hospital | 1 | 0 | 23 | 8 | lower | poor |

| 2 | 11 | 3 | 3 | hospital | 1 | 1 | 23 | 0 | higher | less poor |

| 2 | 12 | 5 | 1 | hospital | 0 | 0 | 18 | 10 | higher | less poor |

| 2 | 13 | 5 | 2 | hospital | 0 | 1 | 24 | 5 | lower | poor |

| 2 | 14 | 2 | 1 | hospital | 0 | 0 | 19 | 5 | higher | less poor |

| 3 | 15 | 7 | 1 | hospital | 0 | 0 | 21 | 5 | lower | poor |

| 3 | 16 | 7 | 4 | hospital | 2 | 1 | 28 | 0 | lower | poor |

| 3 | 17 | 6 | 5 | hospital | 4 | 0 | 31 | 7 | higher | less poor |

| 3 | 18 | 6 | 4 | hospital | 2 | 1 | 30 | 2 | lower | less poor |

| 3 | 19 | 6 | 3 | hospital | 1 | 1 | 23 | 0 | lower | poor |

| 3 | 20 | 7 | 2 | hospital | 1 | 0 | 20 | 8 | higher | less poor |

Qualitative evidence also supports the idea that, in this sample of women, the JSY cash incentive motivated hospital deliveries. In later interviews, participants spoke openly about this; an upper caste woman, who had delivered her youngest daughter in the government maternity hospital after three home births, said, “people are running after those 1400 rupees.” One of the women who gave birth at home regretted that her labor progressed too quickly to go to the hospital. Her mother-in-law was annoyed that they would not receive the 1400 rupee payment and said that the village health worker—called an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA)—was upset with them for not leaving early enough for the hospital. To put the value of the intended transfer into context, the Planning Commission of the Government of India reported the average monthly per capita expenditure for rural Uttar Pradesh in 2011–2012 to be 1073 rupees (Planning Commission, 2013).

In addition to low pre-program rates of hospital delivery, there are several other reasons why women from the study villages may be more likely to change their behavior as a result of the JSY program than women in other parts of India. First, villages’ proximity to the government maternity hospital means that pregnant women rarely have to pay for transportation to the hospital. Women in the study villages were able to get to the hospital in carts pulled by bicycles, on family members’ motorcycles, or in cycle rickshaws. In contrast, a survey done by the UNFPA found that women in Uttar Pradesh who delivered in health facilities paid on average 294 rupees, or about $6, in transportation costs to reach the facility (UNFPA, 2008).

Second, the hospital studied, unlike smaller public health facilities that give JSY transfers, is a women’s hospital which serves only gynecology patients, and is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Smaller facilities have high rates health worker absence (Chaudhury et al., 2006). The hospital studied is better equipped and staffed than smaller facilities in the area; for instance, some staff are qualified to perform cesarean sections. The hospital reported to the author that over 13,000 deliveries, or more than 35 per day, were performed in 2011, which was more than a three-fold increase over the administrative figure reported for 2006.

The third reason why women from the study villages were particularly likely to respond to JSY is that all three villages have been assigned government village health workers, or ASHAs, who are paid to bring women to the hospital for delivery. The presence of an ASHA is important to the functioning of the program because it gives village level actors an incentive to implement the program, a feature which has been important to the implementation of other government health programs as well (see Spears, 2012 on the Total Sanitation Campaign).

Methods

Participants and data collection

Data for this study come from semi-structured interviews with pregnant and recently delivered women, interviews with government health workers, and observations in villages and at a government maternity hospital. The interview data were collected from January to March, 2012 and from July to August, 2012. Interviews with the women were facilitated by the research assistant and conducted in Hindi and the local dialect. Interviews with government health workers were conducted by the author in Hindi. Detailed field notes were taken about each interview, as well as about each observation.

In each village, a census of women who were at least seven months pregnant at the time of listing, or who had delivered in the two months prior to the listing was taken. Twenty-one women were listed as eligible for the study, but three did not agree to participate. During the course of the study, two additional women joined; one woman came to her parents’ home in a study village in late February and delivered in March, and another who was not identified at the time of listing approached the researcher because she was recently delivered and wanted to participate.

Twenty pregnant and recently delivered women participated in 114 semi-structured interviews. Table 1 presents information about each participant’s birth history, age, years of education, caste, relative economic status, and the number of interviews in which she participated. The number of interviews per participant ranged from 2 to 8, and depended on the woman’s availability; some women returned to their natal villages for holidays during the study period, limiting the number of interviews that could be conducted. Although the author addressed questions to a specific woman in each interview, in practice, the interviewee’s female relatives often joined the interviews.

Individual in-depth interviews were also carried out with government-employed birth workers; these are summarized in table 2. Three ASHAs, who were hired by the government as part of the JSY program in 2008 to work in the study villages, were interviewed in their homes. On paper, ASHAs have many responsibilities, both in their villages and at health facilities. In practice, the ASHAs did the tasks for which they were paid, including accompanying women to the hospital for delivery and for sterilization, and those that were directly supervised by the Auxiliary Nurse Mid-Wife (ANM), a higher ranking government health worker, including calling children to be vaccinated when the ANM visited the village. In principle, it is the ANM’s job to monitor the implementation of the program by holding monthly meetings with the ASHAs. Two of the three ASHAs were observed working with the ANM in the village, and two were observed carrying out their work at the government maternity hospital.

Table 2.

Number of interviews conducted with each type of birth worker

| birth worker ID | role | number of interviews |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ASHA | 3 |

| 2 | ASHA | 3 |

| 3 | ASHA | 3 |

| 4 | nurse | 1 |

| 5 | nurse | 2 |

| 6 | doctor | 2 |

| 7 | doctor | 3 |

| 8 | JSY administrator | 1 |

Between January 2012 and November, 2013, the author visited the government maternity hospital over twenty times to accompany or visit beneficiaries, to interview doctors, nurses, and administrators, and to observe the JSY program. The author presented herself as a doctoral candidate researching maternal and infant health, and in the hospital’s busy atmosphere, dense with women, infants, and their many attendants, she attracted little attention, particularly after the first couple of visits.

Research strategy and data analysis

This project relied on a grounded theory approach. Grounded theory is a methodology in which data collection and analysis proceed iteratively so that analysis informs later stages of data collection and theories emerge from the data (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Charmaz, 1983). The project also made extensive use of observation, using the strategies described in Patton, 1987, who describes how observation allows researchers to gather information on sensitive topics that respondents avoid in interviews, and how it complements and contextualizes the selective perceptions of interviewees. In this project, observation helped the author see beyond the “official government transcript” about the program, which is quite different from how it operates in this context.

In the first stage of data collection, the author developed questions about the JSY program based on initial interviews and observations. This led to a second stage of data collection, in which semi-structured questionnaires were used; these were especially useful for the accounting analysis presented in table 3. The author also observed ASHAs’ visits to women in villages, hospital births and the collection of JSY payments at the hospital. Data analysis involved the development of codes and categories that allowed the author to recognize patterns in the data. Memos and diagrams, or notes based on these codes and categories, were used to draw comparisons between experiences of birth and birth work before and after the program. Such analyses allowed the author to identify gaps in the data; these gaps were filled by a third set of interviews and observations. The final analysis attempted to place the experiences of these particular beneficiaries and birth workers in the broader context of maternal and infant health in rural India.

Table 3.

An estimate of the value of the JSY payment for poorer and less poor families

| Less poor families | Poorer families | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| expense | |||

| transport to hospital | −20 | −20 | |

| fees paid to nurses and ayas | −650 | −500 | |

| supplies from the medical store (including injections, medications and cotton to absorb postpartum blood) | −110 | −110 | |

| soap and/or oil at the hospital | −10 | 0 | |

| chai and snacks in the hospital | −50 | −50 | |

| admission paper | −1 | −1 | |

| blood and urine tests | −50 | −50 | |

| charges for birth certificate and discharge papers | −50 | −50 | |

| payment to ASHA | −200 | −100 | |

| opportunity cost of husband’s time to retrieve and cash the check | −110 | −75 | |

| total expenses | −1251 | −956 | |

| savings | |||

| savings on cord cutting | 21 | 11 | |

| savings on cost of blade to cut cord | 1 | 1 | |

| savings on postpartum massage | 220 | 175 | |

| savings on employing a dhobi | 0 | 50 | |

| total savings | 242 | 237 | |

| JSY payment | 1400 | 1400 | |

| value of JSY payment | 391 | 681 | |

Ethical approval

The study was granted ethical approval by the Internal Review Board at the author’s university.

Results

This section presents the finding that JSY does not improve maternal and infant health because service providers are focused on capturing the economic rents from JSY, and provide an extremely poor quality of care. It also presents detailed accounting of the costs of home and hospital births to show that the net value of JSY transfers to beneficiaries is small. Finally, it documents the emotional and psychological costs to participants of delivering at the hospital.

Government birth workers seek to capture economic rents created by JSY

Government birth workers in the study site have financially benefited from JSY. The three ASHAs who participated in the study are part of a larger group of over 13,600 ASHAs in Uttar Pradesh, whose positions were created between 2005 and 2010 by the National Rural Health Mission (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2012). Rather than receiving a salary, ASHAs are supposed to be paid conditional on performing a variety of village-based health activities. In practice, however, they were rarely paid for activities other than accompanying women to the hospital for delivery. Like JSY payments to beneficiaries, JSY payments to ASHAs are less than the advertised amount. Two of the three ASHAs in the study villages said that one sixth of the JSY payment from every birth is regularly retained by higher ranking health officials.

ASHAs supplement their incomes in several ways. They accept payments from the families of women who they accompany to the hospital. ASHAs earn extra money by offering the services of an ASHA to women who come to the hospital without one. ASHAs can facilitate higher JSY payments for urban women, who, according to the rules of the program, are supposed to receive 1000 rupees instead of 1400. The position of ASHA is seen as a lucrative one compared to other work villagers might do; evidence of this is that ASHAs’ husbands often chose to supervise and facilitate the work of their wives. In doing so, they reduce the cost of transportation to the hospital for their wives (men can drive motorcycles or bicycles, women would have to take a rickshaw), and abide by the socially conservative norms of the society, which frown upon women going to public places, such as the hospital, without a male escort. But, they pay the opportunity cost of their own time.

Hospital staff also gain from the JSY program. Although under the table payment for service was common at the government maternity hospital prior to JSY, the hospital staff now use ASHAs to facilitate payments from patients’ families. Before delivery, ASHAs advise families to save or borrow an appropriate amount of money to bring to the hospital. After delivery, ASHAs locate the woman’s husband or relatives in the public area of the hospital, and bring them news of the baby, and staff members’ request for payment. ASHAs feel compelled to cooperate with this system, both because of their low rank in the health bureaucracy, and because paperwork from nurses facilitates the collection of their own compensation. One ASHA explained that she could not protest her role a rent collector. If she did, she said, “the nurses would write ‘no ASHA’ on the birth certificate.”

In addition to being able to collect payments more easily, hospital staff are receiving payments from more patients than before JSY was implemented. The number of deliveries reported by the maternity hospital more than tripled between 2006 (about 4,100 reported deliveries) and 2011 (about 13,300 reported deliveries). The latter number is likely inflated; the hospital may want to show the state government that it is implementing JSY well, and may over-report the number of patients in order to collect extra JSY payments. However, the participants’ birth histories suggest that many deliveries that would otherwise have occurred at home now occur at the district maternity hospital. According to the head doctor of the hospital, very few additional staff joined during this period.

Further evidence of JSY’s financial benefit to staff was the presence of a young nurse, who was not an official employee of the hospital, in the delivery room. After completing her internship for nursing school at the district maternity hospital, and proving herself to be a hard worker, she was informally allowed to continue working without a salary. Although her outside option was a job in a private clinic paying approximately 10,000 rupees a month, she worked at the hospital for several months, supporting herself on side payments, some fraction of which she paid to higher ranking nurses.

The quality of hospital care is extremely poor

Jeffrey and Jeffrey, 2010’s claim that “[e]ncouraging institutional deliveries without rectifying…serious shortcomings in the modes of operation within government services is a seriously flawed approach” (1717) was supported by the over 20 separate observations that this author made at the hospital. In the crucial moments for survival after birth, babies are routinely left in delivery pans, covered by cloth, and unmonitored, while most of the staff sits outside the delivery room. Often, newborns do not receive basic immunizations before leaving the hospital, and are rarely breastfed after birth despite widespread knowledge of its benefits among hospital staff.

As described in Banerjee et al., 2013, who study maternal mortality in Bihar and Jharkhand, basic emergency maternal care is rarely provided. Women whose deliveries are complicated or dangerous are routinely told to leave hospital, and to seek care in a larger one, more than two hours away. One of the 20 participants in the study, who was severely anemic, was turned out of the hospital after the birth of her daughter, without a blood transfusion, and in serious condition. Although her daughter died before she left the hospital, the staff nonetheless charged her family for delivering the infant. This participant was more fortunate than other women in need of blood transfusions who came to the hospital during the study period; others died in the hospital or after being sent to other facilities.

The value of the JSY transfer is small, and is smaller for less poor than for poorer women

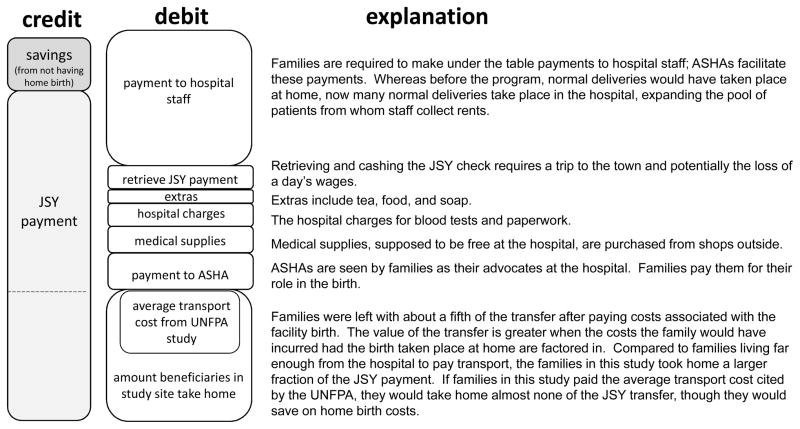

Does the JSY program make an effective wealth transfer to families at a time when they are likely to be spending money on women and infants? In this setting, although JSY does make a net transfer to the families of women who deliver in the government maternity hospital, the amount of that transfer is far less than the amount advertised by the program. Figure 1 summarizes the accounting exercise that is described in this section, averaging over all of the families of women in the study. The left bar, labeled “credit,” depicts the JSY payment that women who give birth in health facilities receive from the government, and the savings their families experience by not having a home birth. The next column, labeled debit, depicts how much of the transfer is used on participation in the JSY program. It clearly shows why the actual value of the transfer is far lower than advertised amount.

Figure 1.

The net value of the JSY payment

Studies of childbirth in Uttar Pradesh have documented that women from different socioeconomic backgrounds have different experiences of childbirth (Jeffrey et al., 1988; Pinto, 2008). Wealthier, higher caste women tend to incur higher costs at the time of a birth than poorer, low caste women, and they tend to observe more post-partum restrictions on movement and work. In many ways, hospital births motivated by JSY payments look more alike for women of different social classes than home births. However, the JSY assistance constituted a larger net transfer to poor families than to less poor families because the latter pay less for services at the time of birth. Families were split into the categories or “poor” and “less poor” based on their observed characteristics of their economic status, including quality of dwelling, quality of food, assets, quality of children’s schooling, etc. Table 3 shows the goods and services that poor and less poor families purchased at the time of the last child’s birth in the government maternity hospital. It estimates the actual value of the JSY transfer by considering both expenses incurred in choosing a hospital birth and the savings from not choosing a home birth.

Although advertised as free, hospital births are not, in practice, free

Although prominently displayed signs in the government maternity hospital declare that the services and medicines are provided free of cost to the patient, in practice, they are not. Nurses send ASHAs to buy supplies, including intramuscular injections of oxytocin and epidosin to speed delivery (see Jeffrey et al. 2007), cotton used to absorb blood after birth, and occasionally medicines from medical shops outside the hospital. Patients also pay for official papers and for tests done at the hospital. Because many recently delivered women want to return home more quickly than the government guidelines mandate after birth, ASHAs retrieve their discharge papers.

Women recognize the work that the ASHAs do on their behalf and see ASHAs as their advocates at the hospital. Tasks regularly undertaken by the three ASHAs in the study include arranging tetanus toxoid injections with the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife, coming to a woman’s house to check on her close to the time of delivery, escorting her to the hospital, dealing with the demands of hospital staff, and arranging paperwork. While women are eager to speak, somewhat angrily, about payments to hospital staff, they are more hesitant to talk about payments to ASHAs. In later interviews, though, nearly all disclosed that their families had paid 100 or 200 rupees to the ASHA, depending on their means.

It is noteworthy that the largest single expense associated with a hospital delivery is the under the table fees paid to the hospital staff. Families from the study villages paid between 500 and 700 rupees to hospital staff on duty when they were admitted or when their babies were born. Relatively better off families paid more for deliveries, as did families who had boys rather than girls. The higher payments by families who have boy babies can be understood in the context of Indian son-preference (Arnold et al., 1998; Das Gupta, 1987): families whose babies are boys are happier about the birth, more thankful to hospital staff, and therefore willing to make higher payments.

Although district officials and hospital administrators publicly claim that women do not pay for delivery at the district maternity hospital, ASHAs know better than to make such promises to pregnant women. One ASHA explained how she convinces families to bring pregnant women to the hospital: “I tell them, maybe there are seven or eight hundred rupees of spending at the hospital, but you are getting two or three hundred more than that.” Her statement reflects the reality that the program transfers much less than the advertised 1400 rupees to beneficiaries; indeed, her estimate of the transfer is actually quite close to difference between the payment and the total expenses listed in table 3.

A final cost associated with participating in the program is the opportunity cost of retrieving the check for the JSY payment and cashing it at a bank. Husbands miss a day of work to accompany their wives and infants to retrieve the payment. Many of the husbands work as day laborers or rickshaw pullers. The loss of wages for table 3 was calculated based on reported daily wages, and adjusted down to reflect that husbands do not find work every day.

Delivery at the hospital saves on some home birth expenses, but not all

A calculation of the transfer should take into account that families would have incurred different expenses if the birth had taken place at home. Women described how, after home births, a family member is sent to buy a clean blade from the shop, and to summon the low caste birth worker, who will cut the umbilical cord, clean up the room where the birth took place, and dispose of the blood and placenta. In the 5 to 10 days following a birth, this low caste birth worker comes to the woman’s house to massage and bathe the mother. (See Pinto, 2008 for a more complete description of this work.) Table 3 gives the approximate cost of this service.

Following home births, most families hire a dhobi, or washerman, because the cloths on which a woman bleeds during childbirth are considered ritually dirty. Regular washing by the household’s women will not get them clean; they should be cleaned by someone from the dhobi caste. However, in the case of a hospital birth, many lower caste families did not hire a dhobi, explaining that “all of the dirtiness happened there.” For both Hindu and Muslim higher caste families, though, delivering in the hospital does not change the calculus of whether or not to hire a dhobi after a birth. As the mother-in-law of a high caste Muslim family explained, “even if we throw the cloths [used in the hospital] out, we still have to call the dhobi, so that other people see this.”

The two types of families saved approximately the same amount of money, about 250 rupees, by delivering in the hospital rather than at home. Adding the savings and the JSY payment, and subtracting the expenses yields a net transfer of about 400 rupees from the JSY program for less poor families and about 700 rupees for poorer families.

Giving birth at the hospital is emotionally and psychologically taxing

The previous section documented that the actual value of the JSY transfer is less than the advertised transfer. The non-monetary costs of hospital births are more difficult to quantify. Both groups of women—those who are relatively poor in their villages and those who are relatively better off—are subject to demeaning treatment at the government maternity hospital.

The following is an excerpt from field notes taken during a interview with Lilam, a poor, low caste young woman, and her female relatives:

Interviewer: “How was it in the hospital?”

Lilam looked up, narrowed her eyes, pursed her lips, and looked back down at the pot she was scrubbing with sand. She did not respond.

Interviewer: “So you did not have an OK time in the hospital?”

Lilam: “No.”

She did not look up from the pot she was scrubbing.

Interviewer: “Why not?”

When Lilam looked up, she gave the impression she might be about to cry. She started to respond, hesitated, and then looked back down at her work.

Interviewer: “Was it because of the pain, or the money, or something else?”

Lilam: “There will be pain [when someone gives birth], it was because of the money.”

Lilam went on to explain that her husband fought with the staff to try to avoid paying them the money he had scrambled to borrow from neighbors before they left for the hospital.

Eventually, he paid 480 rupees so that she could be admitted.

Interviewer: “So what would happen if you said that you weren’t going to pay?”

Lilam’s mother-in-law: “If you don’t pay, they don’t look at you, or admit you, or cut the cord. If you don’t pay, they turn you out.”

Lilam’s female relative: “The hospital was built to help people, but if you don’t pay, they run you off.”

During the exchange with her female relatives, Lilam was quiet, seemingly grateful that her female relatives had joined the interview. She did not seem to want to talk much about the demeaning and vulnerable situation that the hospital staff had put her in: without their cooperation, she would not be eligible for the JSY transfer, but without a large, upfront payment, they would not permit her to deliver there.

Ramila, an upper caste woman, had delivered three children at home before giving birth in the hospital. She described how stressful an experience the hospital delivery had been, particularly because the nurses seemed to be in such a hurry for her to deliver. She said: “the nurses at the hospital don’t want it [labor] to take any time at all, they want everything to happen quickly!” The medical details Ramila gave of the birth seem to support this analysis. She was given labor-inducing intramuscular injections and an episiotomy, despite having delivered three children without episiotomies, and despite the hospital’s policy (stated by the head doctor) of doing episiotomies only for first births. Ramila, who did not consent to the episiotomy, explained why, she believed, it had been done: “if it takes even a little bit of time, then the nurses go straight to the operation.”

While it is possible that there was a valid medical reason for the episiotomy, it is significant that Ramila was not aware of it. It is noteworthy that the birth of Ramila’s baby happened only a few minutes before the nurses changed shifts, suggesting that the nurse who attended Ramila may have been in a hurry to collect payment for Ramila’s delivery, rather than forfeiting it to the next nurse on duty. Reflecting on whether she would give birth at the hospital again, Ramila said that “going to the hospital is completely useless…we should have our pains at home.” Other high caste women and their mothers-in-law echoed this sentiment. Upon being asked whether the costs of going to the hospital outweighed the benefit of the JSY payment, Najma’s mother-in-law, high caste Muslim woman, answered emphatically, “It is only good [to give birth] at home!”

The treatment described by these two women is consistent with observations made at the hospital—women were yelled at, slapped by hospital staff, and badgered for higher payments, and episiotomies were routinely performed without permission and stitched without local anesthesia. It is similarly consistent with treatment of patients described by Jeffrey and Jeffrey, 2010, who write about “staff who embezzle government funds, extort money illegally and treat patients in distress in discriminatory, demeaning and punitive ways” (1717). Although it is beyond the scope of this study to explore the following hypothesis in detail, it is important to mention that the JSY program may actually exacerbate poor treatment at the hospital. Overcrowding may lead to more short-tempered behavior on the part of the nurses. Additionally, higher willingness to pay on the part of patients, caused by the future JSY payment, may lead to their greater tolerance for corruption and rough treatment.

These data highlight two important patterns about the non-monetary costs of births at the hospital. The first is that both groups of women seem to experience high psychological costs of hospital births. The second is that better-off women are more likely express the idea that going to the hospital was, in the end, not worth the costs. Perhaps this is because they and their families are less accustomed to demeaning treatment, and it may also be because the value of the transfer they receive is less in both absolute and relative terms than the transfer received by poorer people.

Conclusion

This study has addressed the question of why the JSY program, which motivates many women to go to the hospital for birth, does not improve health outcomes. It finds that service providers, who are focused on capturing the rents from JSY, provide an extremely poor quality of care. This study also examined the value of the program to beneficiaries, since, even if the conditionality of a cash transfer program does not improve outcomes, it might still be worthwhile to transfer money to families in poverty in a time of need. Indeed, some scholars believe that JSY is accomplishing that. In a recent article for the popular press, Glassman and Birdsall, 2013 praise JSY, saying that the increase in facility-based births is evidence that “the best way to let poor people have more money is give it to them.”

However, this study’s accounting of the costs of hospital delivery suggests that, in this instance, the program did not importantly transfer wealth to the families at the time of birth. In the study site, the value of the transfer received by poorer women is greater than that received by less poor women, but both groups receive far less than the 1400 rupees promised by the JSY program. It is important to note that in most other rural places, the value of the transfer would be even lower than it was in the study site because of the costs of transportation to the health facility. This study also documents the psychological and emotional costs of delivering at the hospital, which arise from the maltreatment of women and their families by hospital staff. These costs need to be considered in the broader discussion of JSY’s costs and benefits.

The findings on quality of care, the low value of the transfer and mistreatment at the hospital raise the question: why do families participate in the program? Although it is beyond the scope of this study to address this question in detail, social pressure used by ASHAs and the fact that pregnant women, who have low intra-household rank, often do not decide where they will give birth are potentially important reasons. However, there are open questions about whether families, after having had an initial experience with JSY, will continue to opt for facility-based deliveries, and whether hospital staff may be motivated to charge smaller under the table fees to maintain interest in hospital delivery.

Ultimately, the JSY program does nothing to restructure health worker incentives to improve the quality of care provided to mothers and infants, nor does it provide a substantial transfer of resources to families at a time when they might otherwise be investing in women and infants. In other words, when mothers are paid to be physically present in facilities, health service providers in contexts such as this one seek to capture rents from the program, but have little incentive to improve health outcomes. These findings suggest the need for a substantial rethinking of the JSY program with careful attention to incentivizing health outcomes.

Highlights.

Qualitative study of India’s conditional cash transfer for birth in health facilities drawing on fieldwork in Uttar Pradesh

Addresses why the program has not improved health despite increasing hospital births

Finds that health workers capture economic rents of the program and provide poor quality care

Finds that the net monetary value of participation is low and psychological costs are high

Suggests that the program should be restructured to incentivize health outcomes

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge helpful comments from Elizabeth Armstrong, Veena Das, Josephine Duh, Jeffrey Hammer, Reetika Khera, three anonymous reviewers, and especially Elizabeth Chiarello, Sara McLanahan and Dean Spears. Baby Parveen Qurreshi provided excellent and indispensible research assistance. All errors are my own. Partial support for this research was provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant #5R24HD047879).

Footnotes

The district that was studied was more disadvantaged than the state as a whole. The 2011 census reported a district female literacy rate of 42%, compared to the state’s 59%, a scheduled caste population of 32%, compared to the state’s 21%, and an electrification rate of 13%, compared to the state’s 37%.

The Government of India’s Annual Health Survey of 2011 found that 47% of births in that year took place in an institution.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Accountability Initiative. Technical report, Budget Brief. 2012. National Rural Health Mission: GoI, 2011–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Khan M. Is demand side financing equity enhancing? Lessons from a maternal voucher scheme in Bangladesh. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;72(10):1704–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annual Health Survey. Technical report. Government of India: 2011. Annual health survey: Uttar Pradesh. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold F, Choe MK, Roy TK. Son Preference, the Family-Building Process and Child Mortality in India. Population Studies. 1998;52:301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Basinga P, Gertler PJ, Binagwaho A, Soucat AL, Sturdy J, Vermeersch CM. Effect on maternal and child health services in Rwanda of payment to primary health-care providers for performance: an impact evaluation. The Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1421–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, John P, Singh S. Stairway to death: Maternal mortality beyond the numbers. Economic and Political Weekly. 2013;XLVIII(31):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Duflo E, Glennester R. Putting a band-aid on a corpse: Incentives for nurses in the Indian health care system. Journal of the European Economic Association. 6(2–3):487–500. doi: 10.1162/JEEA.2008.6.2-3.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Z, Gupta I, DeSilva H, Manandhar D, Awasthi S, Moazzem Hossain SM, Salam MA. Maternal and child health: Is South Asia ready for change? British Medical Journal. 2004;328:816–819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonu S, Bhushan I, Rani M, Anderson I. Incidence and correlates of ‘catastrophic’ maternal health care expenditure in India. Health Policy and Planning. 2009;24:445–456. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A. Health, income and economic development. In: Pleskovic B, Stern N, editors. Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics. World Bank; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. The grounded theory method: An explication and interpretation. In: Emerson R, editor. Contemporary field research: A collection of readings. Waveland Press; 1983. pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury N, Hammer J, Kremer M, Muralidharan K, Rogers H. Missing in action: Teacher and health worker absence in developing countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(1):91–116. doi: 10.1257/089533006776526058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeson M, Bos E, Mawji T, Pathmanathan I. Reducing child mortality in India in the new millennium. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:1192–1199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Hammer J. Money for Nothing: The dire straits of medical practice in Delhi, India. Journal of Development Economics. 2007;83(1):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Das Gupta Monica. Selective discrimination against female children in rural Punjab, India. Population and Development Review. 1987;13:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dongre A. Effect of monetary incentives on institutional deliveries: Evidence from India. 2010. working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Ensor T, Clapham S, Prasai DP. What drives health policy formulation?: Insights from the Nepal maternity incentive scheme. Health Policy. 2009;90(2–3):247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman A, Birdsall N. Can India defeat poverty? Foreign Policy. 2013 available online: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2013/01/08/can_india_defeat_poverty.

- Planning Commission. Technical report. Government of India: 2013. Press note on poverty estimates. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey P, Jeffrey R, Lyon A. Labour pains and labour power: Women and childbearing in India. Zed Books Ltd; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery P, Das A, Dasgupta J, Jeffery R. Unmonitored intrapartum oxytocin use in home deliveries: Evidence from Uttar Pradesh, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 2007;15(30):172–178. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery P, Jeffery R. Only when the boat has started sinking: A maternal death in rural north India. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71:1711–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan ME, Hazra A, Bhatnagar I. Impact of Janani Suraksha Yojana on selected family health behaviors in rural Uttar Pradesh. Journal of Family Welfare. 2010;(56):9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Mohanty S, Kumar A, Misra R, Santosham M, Awasthi S, Baqui A, Singh P, Singh V, Ahuja R, Singh JV, Malik GK, Ahmed S, Black R, Bhandari M, Darmstadt G. Effect of community-based behavior change management on neonatal mortality in Shivgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61483-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Dandona L, Hoisington J, James S, Hogan M, Gakidou E. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: An impact evaluation. The Lancet. 2010;375:2009–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malini S, Tripathi RM, Khattar P, Nair KS, Tekhre YL, Dhar N, Nandan D. A rapid appraisal on functioning of Janani Suraksha Yojana in south Orissa. Health and Population: Perspectives and Issues. 2008;31(2):126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar S, Mills A, Powell-Jackson T. Financial incentives in health: New evidence from India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana. 2011. working paper. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Rural Health Mission. 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/NRHM.htm.

- Mohanty S, Srivastava A. Out-of-pocket expenditure on institutional delivery in India. Health Policy and Planning. 2012:1–16. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs057. advanced access. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Rural Health Mission. Technical report. Government of India: 2009. National Rural Health Mission (2005–2012): Mission document. [Google Scholar]

- Nuygen H, Hatt L, Islam M, Sloan N, Chowdhury J, Schmidt J, Hossain A, Wang H. Encouraging maternal health service utilization: An evaluation of the Bangladesh voucher program. Social Science and Medicine. 2012;74(7):989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Registrar General. Technical report. Sample Registration System; Government of India: 2013. Special Bulletin on Maternal Morality in India: 2010–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. How to use qualitative methods in evaluation. Sage Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto S. Where there is no midwife: Birth and loss in rural India. Berghahn Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Jackson T, Hanson K. Financial incentives for maternal health: Impact of a national programme in Nepal. Journal of Health Economics. 2012;31:271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Shanker S. Tying their hands? Institutional obstacles to the success of the ASHA community health worker programme in rural north India. AIDS Care. 2010;22(s2):606–612. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidney K, Diwan V, El-Khatib Z, de Costa A. India’s JSY cash transfer program for maternal health: Who participates and who doesn’t – a report from Ujjain district. Reproductive Health. 2012;9(2):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens C. Training urban traditional birth attendants: Balancing international policy and local reality: Preliminary evidence from the slums of India on the attitudes and practice of clients and practitioners. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;35(6):811–817. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Spears D. Effects of rural sanitation on infant mortality and human capital: Evidence from India’s Total Sanitation Campaign. 2012. working paper. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Concurrent assessment of Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) in selected states: Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. UNFPA; 2008. technical report. [Google Scholar]

- Witter S, Khadka S, Nath H, Tiwari S. The national free delivery policy in Nepal: Early evidence of its effects on health facilities. Health Policy and Planning. 2011;26(suppl 2):ii84–ii91. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]