Abstract

Background: Epidemiologic literature suggests that exposure to air pollutants is associated with fetal development.

Objectives: We investigated maternal exposures to air pollutants during weeks 2–8 of pregnancy and their associations with congenital heart defects.

Methods: Mothers from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, a nine-state case–control study, were assigned 1-week and 7-week averages of daily maximum concentrations of carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, and sulfur dioxide and 24-hr measurements of fine and coarse particulate matter using the closest air monitor within 50 km to their residence during early pregnancy. Depending on the pollutant, a maximum of 4,632 live-birth controls and 3,328 live-birth, fetal-death, or electively terminated cases had exposure data. Hierarchical regression models, adjusted for maternal demographics and tobacco and alcohol use, were constructed. Principal component analysis was used to assess these relationships in a multipollutant context.

Results: Positive associations were observed between exposure to nitrogen dioxide and coarctation of the aorta and pulmonary valve stenosis. Exposure to fine particulate matter was positively associated with hypoplastic left heart syndrome but inversely associated with atrial septal defects. Examining individual exposure-weeks suggested associations between pollutants and defects that were not observed using the 7-week average. Associations between left ventricular outflow tract obstructions and nitrogen dioxide and between hypoplastic left heart syndrome and particulate matter were supported by findings from the multipollutant analyses, although estimates were attenuated at the highest exposure levels.

Conclusions: Using daily maximum pollutant levels and exploring individual exposure-weeks revealed some positive associations between certain pollutants and defects and suggested potential windows of susceptibility during pregnancy.

Citation: Stingone JA, Luben TJ, Daniels JL, Fuentes M, Richardson DB, Aylsworth AS, Herring AH, Anderka M, Botto L, Correa A, Gilboa SM, Langlois PH, Mosley B, Shaw GM, Siffel C, Olshan AF, National Birth Defects Prevention Study. 2014. Maternal exposure to criteria air pollutants and congenital heart defects in offspring: results from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Environ Health Perspect 122:863–872; http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307289

Introduction

Epidemiologic studies provide inconsistent evidence of an association between exposure to air pollutants and congenital heart defects (CHDs) (Agay-Shay et al. 2013; Dadvand et al. 2011a, 2011b; Dolk et al. 2010; Gilboa et al. 2005; Hansen et al. 2009; Padula et al. 2013; Rankin et al. 2009; Ritz et al. 2002; Strickland et al. 2009; Vrijheid et al. 2011). A recent meta-analysis identified two associations: nitrogen dioxide (NO2) exposure and tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) exposure and coarctation of the aorta (COA) (Vrijheid et al. 2011). However, only five defects/defect groupings were explored.

Most previous studies used monitoring data and assigned exposure by averaging daily pollutant averages over postconception weeks 3–8. This method does not capture the temporal variability in exposure across windows with greater impact on cardiac development, which could mask or attenuate associations. Using daily maximum concentrations, as opposed to averages, to calculate exposure would better capture daily exposure peaks and more closely parallel regulatory standards issued by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA 2012). Teratogenic models have suggested that environmental insults have a threshold below which there is no observed impact on the fetus (Dolk and Vrijheid 2003). Based on these past models of teratogenicity, the higher exposures represented by daily maxima could be more relevant to disruption of cardiac development. Separating a single overall average into weekly averages would also allow for the exploration of specific windows of susceptibility and reduce potential misclassification of exposure.

In this study we used data from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS), a large population-based case–control study of birth defects, to investigate the association between CHDs in offspring and ambient concentrations of the following criteria air pollutants during early pregnancy: carbon monoxide (CO), NO2, ozone (O3), particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 10 μm (PM10), particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm (PM2.5), and SO2.

Methods

Study population. The NBDPS recruits cases from population-based, active surveillance congenital anomaly registries in nine U.S. states and includes live births and stillbirths > 20 weeks gestation or at least 500 g, as well as elective terminations of prenatally diagnosed defects when available (Yoon et al. 2001). Arkansas, Iowa, and Massachusetts ascertain cases statewide, whereas California, Georgia, New York, North Carolina, Texas, and Utah ascertain cases in select counties. Cases are reviewed by clinical geneticists using standardized study protocols to determine study eligibility and classification, and cases with chromosomal/microdeletion disorders and disorders of known single-gene deletion causation are excluded. Controls are unaffected livebirths who are randomly selected from vital records or hospital records, depending upon study center. The NBDPS has been approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of all participating centers, and all participants provided written or oral informed consent before participation. These analyses were reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina IRB.

For this analysis, the study population consisted of all controls and eligible cases with a simple, isolated CHD (i.e., a single CHD with no extra-cardiac birth defects present) and an estimated date of delivery (i.e., due date) from 1 October 1997 through 31 December 2006. During this time period, the participation response was 69% among all cases and 65% for controls. Within the NBDPS, a team of clinicians with expertise in pediatric cardiology reviewed information abstracted from the medical record and centrally assigned a single, detailed cardiac phenotype to each case whose diagnosis was confirmed by echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, surgery, or autopsy and documented in the medical record. Phenotypes were then aggregated into individual CHDs and defect groupings (Botto et al. 2007). The following additional groups were created because of limited sample size of individual defects: a) other conotruncal defects, which included common truncus, interrupted aortic arch–type B (IAA-type B), interrupted aortic arch–not otherwise specified (IAA-NOS), double outlet right ventricle associated with transposition of the great arteries (DORV-TGA) and not associated with TGA (DORV-other), and conoventricular septal defects (VSD-conoventricular); and b) atresias that included both pulmonary and tricuspid atresia. Simple, isolated CHD cases represented 64% (n = 12,383) of the total CHD cases. We restricted the analysis to offspring with a single CHD to create more etiologically homogeneous case groups, although this limits the generalizability of our findings. Women who reported having pregestational diabetes (types 1 and 2) during their pregnancy were excluded owing to the established association with CHD (Correa et al. 2008). Women living > 50 km from a pollutant-specific air monitor were excluded from that analysis.

Exposure assignment. Each woman reported the due date that was provided by her clinician during pregnancy to obtain the gestational age of the infant at birth. Using the gestational age to estimate the date of conception, we assigned calendar dates to each week of pregnancy. Women’s residential addresses during pregnancy were centrally geocoded to ensure consistency across study centers. Each geocoded address during weeks 2–8 of pregnancy was matched to the closest air monitor for each pollutant, with > 50% of the data available using ArcGISv10 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) and monitor locations obtained from U.S. EPA’s Air Quality System (U.S. EPA 2013). Participants from 1996–1998 were excluded from the analysis of PM2.5 because monitoring began in 1999.

We used the daily maximum hourly measurement for CO, NO2, and SO2, the daily maximum 8-hr average for O3, and 24-hr measurements of PM10 and PM2.5 to assign exposure. We averaged over the daily maximum or 24-hr measurements for weeks 2–8 of pregnancy to assign a 7-week and also 1-week averages of the daily values. We included week 2 in addition to the standard window of cardiac development, because of the potential for lag effects of air pollution (van den Hooven et al. 2012). If only a single measurement was taken during a given week, it was assigned as the weekly exposure. Ambient levels of each pollutant except O3 were categorized into the following categories, using the distribution of pollutant concentration among controls: less than the 10th centile (referent), 10th centile to less than the median, the median to less than the 90th centile, and greater than or equal to the 90th centile. These categories captured the departure from linearity observed in initial, exploratory analyses (data not shown). For similar reasons, O3 was categorized into quartiles. Centiles were calculated separately for the 7-week and 1-week measures of exposure.

Statistical analysis. The following variables obtained from the maternal interview were identified as potential confounders through directed acyclic graph analysis (Greenland et al. 1999) and included in the final adjustment set: maternal age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, tobacco smoking in the first month of pregnancy, alcohol consumption during the first trimester, and maternal nativity. Maternal age was represented as a single, continuous term, measured at the time of conception. Race/ethnicity was self-reported and categorized into the following groups: white non-Latino, black non-Latino, Latino, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other. Educational attainment was collapsed into six categories: 0–6 years of education, 7–11 years, high school graduate or equivalency, 1–3 years of college or trade school, 4 years of college or completion of a bachelor’s degree, and an advanced degree. Household income was self-reported as < $10,000 annually, > $50,000 annually, or in-between. We adjusted for any tobacco use in the first month of pregnancy and differentiated between some alcohol consumption (less than four drinks) and binge drinking (four or more drinks) during the first trimester. Maternal nativity was defined as self-report of being born outside the United States.

To account for potential differences in case ascertainment by study center, models were also adjusted for the center-specific ratio of septal defects to total CHDs. Identifying septal defects often depends on method of case ascertainment (Martin et al. 1989). All potential confounders, as well as distance to major roadway, prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), and maternal occupation status during pregnancy were assessed for effect measure modification by constructing logistic regression models with and without interaction terms and conducting likelihood ratio tests using an a priori alpha level of 0.1. Distance to the closest major road—defined as an interstate, U.S. highway, state, or larger county highway—was constructed using ArcGISv10 and then dichotomized at 50 m. Prepregnancy BMI was defined using self-reported maternal height and weight and categorized according to National Institutes of Health (1998) guidelines into underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25), overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30), and obese (BMI ≥ 30). Maternal occupation status was defined as ever working outside the home during any time during pregnancy.

For each pollutant, models were constructed to explore individual defects and defect-groupings. If a woman did not have at least one monitoring value for each week of exposure, she was excluded from the weekly analysis. We explored the relationships between all weeks and all defects because of uncertainty in pregnancy dating when using an estimated date of conception and the lack of clearly elucidated mechanisms by which cardiac development could be disrupted by exposure to air pollution. Animal research suggests that exposures outside the typical period of development for an individual heart structure could also be etiologically relevant (Morgan et al. 2008).

Because we simultaneously assessed multiple weeks of exposure and multiple defects/groupings, we constructed two-stage hierarchical regression models to account for the correlation between estimates and partially address multiple inference (Greenland 1992; Witte et al. 1998). The first-stage, represented in Equation 1, was an unconditional, polytomous logistic regression model of individual CHDs on exposure (x) defined as either all 1-week averages of maximum or 24-hr pollutant values or the single 7-week average, and the full adjustment set (w) detailed above.

|

[1] |

bd is the vector of regression coefficients corresponding to pollutant exposure for an individual CHD (d), cd is the vector of regression coefficients corresponding to the covariates for a given defect, and m is the total number of individual types of CHDs. The second-stage model, which defines how the first-stage betas are associated, is given in Equation 2:

βi = Zir + δi, [2]

where Zi is a row in the design matrix that includes an intercept term and then indicator variables for type of defect, broader defect grouping, and exposure week/level for the ith β, r is the vector of coefficients corresponding to the variables included in the design matrix, and δi are independent normal random variables with a mean of zero and a variance of τ2 that describe the residual variation in βi. The obtained second-stage coefficients, r, are used to estimate values toward which the first-stage coefficients will be shrunk, with the magnitude of the shrinkage depending on the precision of the maximum-likelihood estimate obtained in stage 1 and the value of the second-stage variance, τ2 (Greenland 1992; Witte et al. 1998). We fixed τ2 at 0.5, corresponding to a prior belief with 95% certainty that the residual odds ratio (OR) will fall within a 16-fold span.

To assess whether our results were robust to changes in model specification, we conducted sensitivity analyses by setting the value of τ2 to 0.25, corresponding to a 7-fold OR span, as well as to a value of 1, corresponding to a 50-fold span. We also explored different specifications for the design matrix, in turn defining the prior value as a common mean for all defects, a common mean for each defect, or a common mean for each exposure week/level, across defects. Individual defects with > 10 but < 100 cases were excluded from hierarchical models and explored using Firth’s penalized maximum-likelihood method to address the quasi-complete separation that occurred due to small sample size (Heinze and Schemper 2002). These defects included the individual defects collapsed into the other conotruncals and atresia categories described above; Ebstein’s anomaly, which was part of the right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO) defect grouping; and muscular ventricular septal defects (VSDmuscular), which was part of the septal defect-grouping. IAA-type A and partial anomalous pulmonary venous return had < 10 cases each and were excluded from all individual analyses, but were included in the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) and anomalous pulmonary venous return (APVR) defect groupings, respectively. To assess whether pollutant–defect relationships conformed to a monotonic dose response, we reanalyzed the data using incremental coding which compares each category of exposure to its immediate predecessor. If the incremental ORs are all above (or below) 1, the relationship conforms to a monotonic dose response (Maclure and Greenland 1992).

To explore associations with CHDs within a multipollutant context, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted among participants who lived within 50 km of each type of monitor. PCA is used to reduce the number of correlated variables into a smaller number of artificial variables that capture most of the variance of the original variables while being uncorrelated with each other (Hatcher 1994). This allows the resulting factors to be included within the same model, reducing issues of multicollinearity. Applying PCA, we retained components that accounted for at least the same or more variance than one of the original pollutant variables. We then applied a varimax rotation and calculated factor scores for each participant. These factor scores were categorized using the 10th, 50th, and 90th centiles and used to assign exposure in hierarchical models.

Results

Demographics of the NBDPS controls and CHD defect groupings providing residential address information and eligible to be matched to the closest air monitor for each pollutant are presented in Table 1. Case distribution varied by study site, particularly for the septal defect grouping. The ratios used to adjust for case-ascertainment differences by site are located in the Supplemental Material, Table S1. The percentage of women who lived 50 km from an air pollution monitor varied from 56% for SO2 to 73% for PM10. Demographics were similar across the pollutant-specific populations, although women who lived within 50 km of a SO2 monitor were slightly older and were more likely to be white or African American, work outside the home, have higher household income, and report alcohol consumption during pregnancy (data not shown). The number of cases/controls by exposure distribution for each pollutant are represented in Table 2, along with the pollutant levels that were used to define exposure categories. Median distance to the monitor was similar across pollutants, although women tended to live farther from SO2 monitors and closer to PM2.5 monitors.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of geocoded, nonpregestational diabetic population of CHD groupings and controls, National Birth Defects Prevention Study (1997–2006).

| Demographics | Controls | APVR | AVSD | Conotruncal | LVOTO | RVOTO | Septal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | |||||||

| Arkansas | 611 (9.7) | 18 (11.6) | 10 (12.2) | 89 (8.9) | 66 (8.0) | 110 (15.1) | 321 (17.4) |

| California | 871 (13.8) | 27 (17.4) | 5 (6.1) | 159 (15.8) | 111 (13.4) | 60 (8.3) | 110 (6.0) |

| Iowa | 806 (12.7) | 10 (6.5) | 15 (18.3) | 96 (9.6) | 122 (14.7) | 95 (13.1) | 189 (10.2) |

| Massachusetts | 916 (14.5) | 28 (18.1) | 15 (18.3) | 187 (18.7) | 117 (14.1) | 121 (16.6) | 240 (13.0) |

| Metro Atlanta, Georgia | 750 (11.9) | 19 (12.3) | 11 (13.4) | 140 (13.9) | 99 (11.9) | 92 (12.6) | 231 (12.5) |

| New York | 637 (10.1) | 13 (8.4) | 7 (8.5) | 110 (11.0) | 86 (10.4) | 68 (9.3) | 125 (6.8) |

| North Carolina | 452 (7.1) | 8 (5.2) | 4 (4.9) | 56 (5.6) | 27 (3.3) | 33 (4.5) | 74 (4.0) |

| Texas | 815 (12.9) | 20 (12.9) | 7 (8.5) | 115 (11.5) | 88 (10.6) | 66 (9.1) | 439 (23.8) |

| Utah | 470 (7.4) | 12 (7.7) | 8 (9.8) | 52 (5.2) | 113 (13.6) | 83 (11.4) | 119 (6.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White, non-Latino | 3,797 (60.0) | 89 (57.4) | 62 (75.6) | 612 (61.0) | 592 (71.4) | 474 (65.1) | 1,032 (55.8) |

| Black, non-Latino | 682 (10.8) | 9 (5.8) | 10 (12.2) | 102 (10.2) | 50 (6.0) | 98 (13.5) | 238 (12.9) |

| Latino | 1,460 (23.1) | 44 (28.4) | 4 (4.9) | 221 (22.0) | 159 (19.2) | 116 (15.9) | 467 (25.3) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 168 (2.7) | 7 (4.5) | 3 (3.7) | 35 (3.5) | 13 (1.6) | 13 (1.8) | 53 (2.9) |

| Other | 219 (3.5) | 6 (3.9) | 3 (3.7) | 34 (3.4) | 15 (1.8) | 27 (3.7) | 58 (3.1) |

| Education | |||||||

| 0–6 years | 210 (3.3) | 7 (4.6) | 1 (1.2) | 40 (4.0) | 27 (3.3) | 19 (2.6) | 58 (3.1) |

| 7–11 years | 844 (13.4) | 25 (16.3) | 6 (7.3) | 121 (12.1) | 99 (12.0) | 81 (11.1) | 293 (15.9) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 1,516 (24.1) | 37 (24.2) | 20 (24.4) | 239 (23.9) | 186 (22.5) | 196 (26.9) | 452 (24.5) |

| 1–3 years college or trade school | 1,726 (27.4) | 42 (27.5) | 29 (35.4) | 276 (27.6) | 227 (27.4) | 196 (26.9) | 551 (29.8) |

| 4 years college or Bachelors degree | 1,414 (22.5) | 30 (19.6) | 20 (24.4) | 229 (22.9) | 216 (26.1) | 181 (24.9) | 367 (19.9) |

| Advanced degree | 581 (9.2) | 12 (7.8) | 6 (7.3) | 95 (9.5) | 73 (8.8) | 55 (7.6) | 126 (6.8) |

| Maternal age [years (mean ± SD)] | 27.0 ± 6.1 | 26.7 ± 6.7 | 26.9 ± 5.3 | 27.8 ± 6.2 | 27.8 ± 5.8 | 27.7 ± 6.1 | 27.0 ± 6.5 |

| Nativity | |||||||

| Born in United States | 5,110 (81.2) | 118 (77.1) | 70 (85.4) | 804 (80.4) | 697 (84.2) | 633 (87.0) | 1,527 (82.7) |

| Household income | |||||||

| < $10,000 | 1,066 (18.5) | 26 (19.1) | 13 (16.5) | 167 (17.7) | 105 (13.5) | 109 (16.1) | 351 (20.4) |

| $10,000–$50,000 | 2,695 (46.7) | 69 (50.7) | 41 (51.9) | 410 (43.4) | 368 (47.2) | 321 (47.4) | 853 (49.7) |

| > $50,000 | 2,012 (34.9) | 41 (30.2) | 25 (31.7) | 367 (38.9) | 306 (39.3) | 248 (36.6) | 514 (29.9) |

| Occupational status | |||||||

| Worked outside home | 4,545 (72.1) | 97 (63.4) | 70 (85.4) | 742 (74.2) | 604 (72.9) | 544 (74.7) | 1,279 (69.3) |

| Smoking | |||||||

| First month | 967 (15.3) | 26 (17.0) | 26 (31.7) | 140 (14.0) | 114 (13.8) | 122 (16.8) | 373 (20.2) |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||

| No drinking | 3,981 (63.6) | 101 (67.3) | 50 (61.0) | 603 (60.9) | 550 (66.9) | 473 (66.2) | 1,210 (65.9) |

| < 4 drinks | 1,509 (24.1) | 31 (20.7) | 19 (23.2) | 251 (25.3) | 165 (20.1) | 164 (22.9) | 405 (22.1) |

| ≥ 4 drinks | 770 (12.3) | 18 (12.0) | 13 (15.9) | 137 (13.8) | 107 (13.0) | 78 (10.9) | 222 (12.1) |

| BMI | |||||||

| < 18.5 (underweight) | 316 (5.2) | 8 (5.4) | 4 (5.0) | 50 (5.2) | 34 (4.3) | 25 (3.6) | 96 (5.4) |

| 18.5 to < 25 (normal) | 3,373 (55.4) | 79 (53.7) | 46 (57.5) | 519 (53.5) | 426 (53.8) | 330 (46.9) | 910 (51.0) |

| 25 to < 30 (overweight) | 1,404 (23.1) | 31 (21.1) | 18 (22.5) | 221 (22.8) | 182 (23.0) | 190 (27.0) | 425 (23.8) |

| BMI ≥ 30 (obese) | 993 (16.3) | 29 (19.7) | 12 (15.0) | 180 (18.6) | 150 (18.9) | 159 (22.6) | 354 (19.8) |

| Proximity to roadway | |||||||

| < 50 m | 1,168 (18.5) | 37 (23.9) | 14 (17.1) | 192 (19.1) | 156 (18.8) | 112 (15.4) | 331 (17.9) |

| Values are n (%) unless otherwise noted. | |||||||

Table 2.

CHD cases and controls by exposure level of criteria air pollutants, National Birth Defects Prevention Study (1997–2006; except for PM2.5 1999–2006).

| Pollutant and outcome | < 10th centile | 10th to < 50th centile | 50th to < 90th centile | ≥ 90th centile | Distance to monitor 25th, 50th, 75th centile (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO (ppm) | < 0.58 | 0.58 to < 1.16 | 1.16 to < 2.13 | ≥ 2.13 | 7.0, 14.8, 26.5 |

| Controls (n) | 434 | 1,740 | 1,739 | 436 | |

| All cases (n) | 271 | 1,202 | 1,235 | 308 | |

| LVOTO (n)a | 53 | 249 | 229 | 49 | |

| Aortic stenosis (n) | 12 | 50 | 45 | 10 | |

| COA (n) | 22 | 106 | 80 | 21 | |

| HLHS (n) | 18 | 91 | 102 | 17 | |

| Conotruncal | 66 | 305 | 312 | 70 | |

| dTGA | 22 | 102 | 102 | 21 | |

| TOF | 33 | 162 | 167 | 37 | |

| Other conotruncals | 11 | 41 | 43 | 12 | |

| APVRb | 17 | 42 | 36 | 10 | |

| TAPVR | 15 | 42 | 29 | 10 | |

| AVSD | 5 | 20 | 25 | 3 | |

| RVOTOc | 46 | 202 | 207 | 47 | |

| Pulmonary/tricuspid atresia | 12 | 41 | 39 | 9 | |

| PVS | 33 | 142 | 154 | 36 | |

| Septald | 84 | 382 | 424 | 128 | |

| VSDpm | 47 | 185 | 215 | 54 | |

| ASD | 36 | 172 | 159 | 49 | |

| NO2 (ppb) | < 18.9 | 18.9 to < 33.3 | 33.3 to < 45.5 | ≥ 45.5 | 6.8, 13.7, 25.1 |

| Controls (n) | 396 | 1,584 | 1,591 | 397 | |

| All cases (n) | 248 | 1,088 | 1,152 | 309 | |

| LVOTOa (n) | 43 | 211 | 235 | 56 | |

| Aortic stenosis (n) | 7 | 47 | 42 | 14 | |

| COA (n) | 12 | 74 | 103 | 26 | |

| HLHS (n) | 23 | 86 | 89 | 16 | |

| Conotruncal | 58 | 277 | 285 | 71 | |

| dTGA | 23 | 92 | 99 | 24 | |

| TOF | 27 | 150 | 140 | 38 | |

| Other conotruncals | 8 | 35 | 46 | 9 | |

| APVRb | 16 | 36 | 35 | 13 | |

| TAPVR | 15 | 33 | 32 | 13 | |

| AVSD | 9 | 18 | 22 | 4 | |

| RVOTOc | 38 | 164 | 194 | 63 | |

| Pulmonary/tricuspid atresia | 6 | 41 | 34 | 9 | |

| PVS | 32 | 109 | 143 | 50 | |

| Septald | 84 | 380 | 379 | 101 | |

| VSDpm | 43 | 178 | 189 | 51 | |

| ASD | 36 | 163 | 161 | 35 | |

| O3 (ppb)e | < 32.2 | 32.2 to < 42.9 | 42.9 to < 51.8 | ≥ 51.8 | 6.8, 12.8, 21.9 |

| Controls (n) | 442 | 1,769 | 1,768 | 443 | |

| All cases (n) | 308 | 1,311 | 1,204 | 269 | |

| LVOTOa (n) | 60 | 228 | 223 | 55 | |

| Aortic stenosis (n) | 9 | 47 | 48 | 8 | |

| COA (n) | 23 | 86 | 87 | 27 | |

| HLHS (n) | 27 | 92 | 85 | 20 | |

| Conotruncal | 85 | 300 | 283 | 68 | |

| dTGA | 31 | 92 | 112 | 19 | |

| TOF | 42 | 169 | 135 | 40 | |

| Other conotruncals | 12 | 39 | 36 | 9 | |

| APVRb | 8 | 45 | 47 | 12 | |

| TAPVR | 7 | 41 | 45 | 11 | |

| AVSD | 6 | 17 | 22 | 4 | |

| RVOTOc | 38 | 196 | 202 | 51 | |

| Pulmonary/tricuspid atresia | 7 | 41 | 40 | 10 | |

| PVS | 25 | 142 | 147 | 36 | |

| Septald | 109 | 523 | 427 | 79 | |

| VSDpm | 47 | 203 | 200 | 45 | |

| ASD | 44 | 279 | 196 | 31 | |

| PM10 (μg/m3) | < 14.9 | 14.9 to < 24.2 | 24.2 to < 40.6 | ≥ 40.6 | 6.0, 13.5, 25.2 |

| Controls (n) | 462 | 1,853 | 1,853 | 464 | |

| All cases (n) | 298 | 1,377 | 1,387 | 271 | |

| LVOTOa (n) | 54 | 229 | 276 | 52 | |

| Aortic stenosis (n) | 12 | 54 | 63 | 8 | |

| COA (n) | 15 | 97 | 97 | 22 | |

| HLHS (n) | 24 | 76 | 115 | 21 | |

| Conotruncal | 64 | 295 | 311 | 87 | |

| dTGA | 25 | 97 | 98 | 32 | |

| TOF | 33 | 150 | 175 | 43 | |

| Other conotruncals | 6 | 48 | 38 | 12 | |

| APVRb | 8 | 52 | 45 | 13 | |

| TAPVR | 8 | 45 | 39 | 13 | |

| AVSD | 2 | 25 | 24 | 4 | |

| RVOTOc | 55 | 202 | 225 | 40 | |

| Pulmonary/tricuspid atresia | 16 | 40 | 46 | 6 | |

| PVS | 33 | 151 | 164 | 29 | |

| Septald | 115 | 572 | 503 | 75 | |

| VSDpm | 44 | 227 | 214 | 37 | |

| ASD | 56 | 292 | 233 | 36 | |

| PM2.5 (μg/m3) | < 7.77 | 7.77 to < 12.1 | 12.1 to < 19.7 | ≥ 19.7 | 5.3, 10.4, 20.7 |

| Controls (n) | 440 | 1,763 | 1,763 | 441 | |

| All cases (n) | 378 | 1,420 | 1,212 | 301 | |

| LVOTOa (n) | 66 | 250 | 207 | 73 | |

| Aortic stenosis (n) | 21 | 61 | 39 | 14 | |

| COA (n) | 28 | 92 | 88 | 25 | |

| HLHS (n) | 15 | 95 | 77 | 33 | |

| Conotruncal | 71 | 287 | 291 | 87 | |

| dTGA | 25 | 90 | 95 | 25 | |

| TOF | 35 | 150 | 161 | 50 | |

| Other conotruncals | 11 | 47 | 35 | 12 | |

| APVRb | 14 | 51 | 36 | 13 | |

| TAPVR | 12 | 46 | 32 | 11 | |

| AVSD | 3 | 26 | 27 | 6 | |

| RVOTOc | 58 | 206 | 229 | 47 | |

| Pulmonary/tricuspid atresia | 14 | 46 | 34 | 11 | |

| PVS | 39 | 143 | 178 | 35 | |

| Septald | 166 | 600 | 418 | 75 | |

| VSDpm | 49 | 229 | 222 | 38 | |

| ASD | 115 | 369 | 189 | 36 | |

| SO2 (ppb) | < 3.45 | 3.45 to < 9.7 | 9.7 to < 19.9 | ≥ 19.9 | 8.9, 18.8, 30.2 |

| Controls (n) | 350 | 1,403 | 1,404 | 351 | |

| All cases (n) | 231 | 1,048 | 1,098 | 240 | |

| LVOTOa (n) | 33 | 190 | 200 | 39 | |

| Aortic stenosis (n) | 9 | 39 | 32 | 7 | |

| COA (n) | 13 | 69 | 92 | 21 | |

| HLHS (n) | 10 | 81 | 72 | 11 | |

| Conotruncal | 48 | 221 | 258 | 60 | |

| dTGA | 16 | 76 | 87 | 21 | |

| TOF | 24 | 117 | 133 | 33 | |

| Other conotruncals | 8 | 28 | 38 | 6 | |

| APVRb | 9 | 33 | 35 | 7 | |

| TAPVR | 9 | 27 | 32 | 6 | |

| AVSD | 3 | 14 | 21 | 8 | |

| RVOTOc | 26 | 203 | 183 | 31 | |

| Pulmonary/tricuspid atresia | 8 | 37 | 35 | 5 | |

| PVS | 15 | 155 | 135 | 22 | |

| Septald | 112 | 387 | 398 | 93 | |

| VSDpm | 33 | 164 | 192 | 49 | |

| ASD | 76 | 196 | 151 | 29 | |

| Abbreviations: APVR, anomalous pulmonary venous return; ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; COA, coarctation of the aorta; dTGA, transposition of the great arteries; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstructions; PVS, pulmonary valve stenosis; RVOTO, right ventricular outflow tract obstructions; TAPVR, total anomalous pulmonary venous return; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSDpm, perimembranous ventricular septal defects.aLVOTO grouping also includes cases of interrupted aortic arch–type A, which was not analyzed individually due to limited sample size. bAPVR grouping also includes cases of partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, which was not analyzed individually due to limited sample size. cRVOTO grouping also includes cases of Ebstein’s anomaly, which was not analyzed individually in the hierarchical analysis due to limited sample size. dSeptal grouping also includes cases of muscular ventricular septal defects (VSDmuscular), which was not analyzed individually in the hierarchical analysis due to limited sample size. The exception is PM2.5: VSDmuscular were collected only in the first year of the study when PM2.5 measurements were not available. eO3 exposure was categorized into quartiles using the distribution among the controls. The referent was < 25th percentile, and the other 3 categories were 25 to < 50, 50 to < 75, and ≥ 75. | |||||

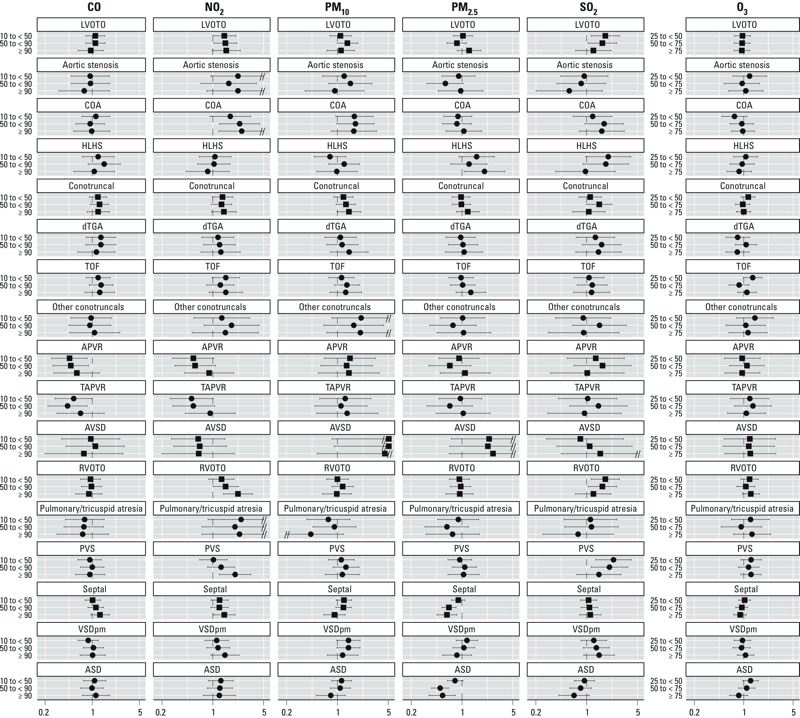

Exposure assigned as a single 7-week average of daily maxima or 24-hr measurements. Figure 1 shows the estimated adjusted ORs and 95% CIs resulting from the hierarchical regression models of the 7-week average exposure to individual pollutants and CHDs (see Supplemental Material, Table S2, for corresponding numerical data). Crude estimates were similar to estimates adjusted for confounders (data not shown). Larger ORs were observed with greater NO2 exposure for individual defects within the LVOTO and RVOTO groupings. Women with the highest average daily maximum exposure to NO2 (> 45.5 ppb) had more than two times the odds of both COA (OR = 2.5; 95% CI: 1.21, 5.18) and PVS (OR = 2.03; 95% CI: 1.23, 3.33) as women with the lowest exposure (< 18.9 ppb). We observed a positive association between SO2 exposure and PVS, although it was attenuated at the highest exposure level (OR for 10th–50th/10th centile contrast = 2.34; 95% CI: 1.33, 4.14; OR for 50th–90th/10th centile contrast = 2.06; 95% CI: 1.16, 3.67; OR for 90th/10th centile contrast = 1.48; 95% CI: 0.74, 2.97). Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) was associated with exposure to PM2.5 (90th/10th centile contrast: OR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.07, 3.89) but not NO2. We observed increased odds of perimembranous ventricular septal defects (VSDpm) (OR for 90th/10th centile contrast = 1.48; 95% CI: 0.91, 2.42) and reduced odds of atrial septal defects (ASD) (OR for 90th/10th centile contrast = 0.67; 95% CI: 0.41, 1.09) with SO2 exposure. We also observed reduced odds of ASDs with exposure to PM2.5 (OR for 50th–90th/10th contrast = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.38, 0.65; OR for 90th/10th contrast = 0.54; 95% CI: 0.35, 0.81). Although imprecise, the effect estimates for APVR and CO and NO2 exposures indicated lower odds with greater exposure, although the negative association was attenuated at the highest exposure level. The associations between NO2 and PVS, NO2 and COA, SO2 and VSDpm, and SO2 and ASDs increased monotonically with increasing exposure (data not shown). For both PM10 and NO2, we found evidence of effect measure modification by distance to a major road in first-stage maximum likelihood models, using our a priori criterion of a likelihood ratio test p-value < 0.1 (PM10 likelihood ratio test: χ2 = 30.5, p = 0.03; NO2 likelihood ratio test: χ2 = 34.5, p = 0.01). In both cases, ORs were generally greater for women who lived within 50 m of a roadway (see Supplemental Material, Table S3).

Figure 1.

Estimated adjusted ORs and 95% CIs between CHDs and 7-week average of daily maxima/24-hr measures of criteria air pollutants, National Birth Defects Prevention Study 1997–2006 (for PM2.5, 1999–2006). Abbreviations: APVR, anomalous pulmonary venous return; ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; COA, coarctation of the aorta; dTGA, transposition of the great arteries; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstructions; PVS, pulmonary valve stenosis; RVOTO, right ventricular outflow tract obstructions; TAPVR, total anomalous pulmonary venous return; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSDpm, perimembranous ventricular septal defects. Other conotruncal category includes common truncus, interrupted aortic arch–type B and type not specified, double outlet right ventricle defects, and conoventricular septal defects. A double slash (//) indicates truncation of the results. Squares indicate defect groupings; circles indicate individual defects. Defect groupings include all individual defects listed underneath with the following additions: LVOTO, IAA‑type A; APVR, partial APVR; RVOTO, Ebstein’s anomaly; Septal, muscular venricular septal defects (VSDmuscular), except for PM2.5. VSDmuscular were collected only in the first year of study when no PM2.5 data were available. Those defects could not be analyzed within the hierarchical regression due to limited sample size. ORs were estimated from hierarchical regression models. First stage was a polytomous logistic model, adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity, age educational attainment, household income, maternal smoking status and alcohol consumption during early pregnancy, nativity, and site-specific heart defect ratio. Second stage was a linear model with indicator variables for defect, defect grouping, and level of exposure. For all pollutants except O3, the three categories of exposure are as follows: 10th centile to < 50th centile, 50th centile to < 90th centile, and ≥ 90th centile, with the referent level being < 10th centile among controls. For ozone, the three categories of exposure were 25th to < 50th centile, 50th centile to < 75th centile, and ≥ 75th centile, with the referent grouping being below the 25th centile. Pollutant levels that define the category cut points are provided in Table 2. See Supplemental Material, Table S2, for corresponding numeric data.

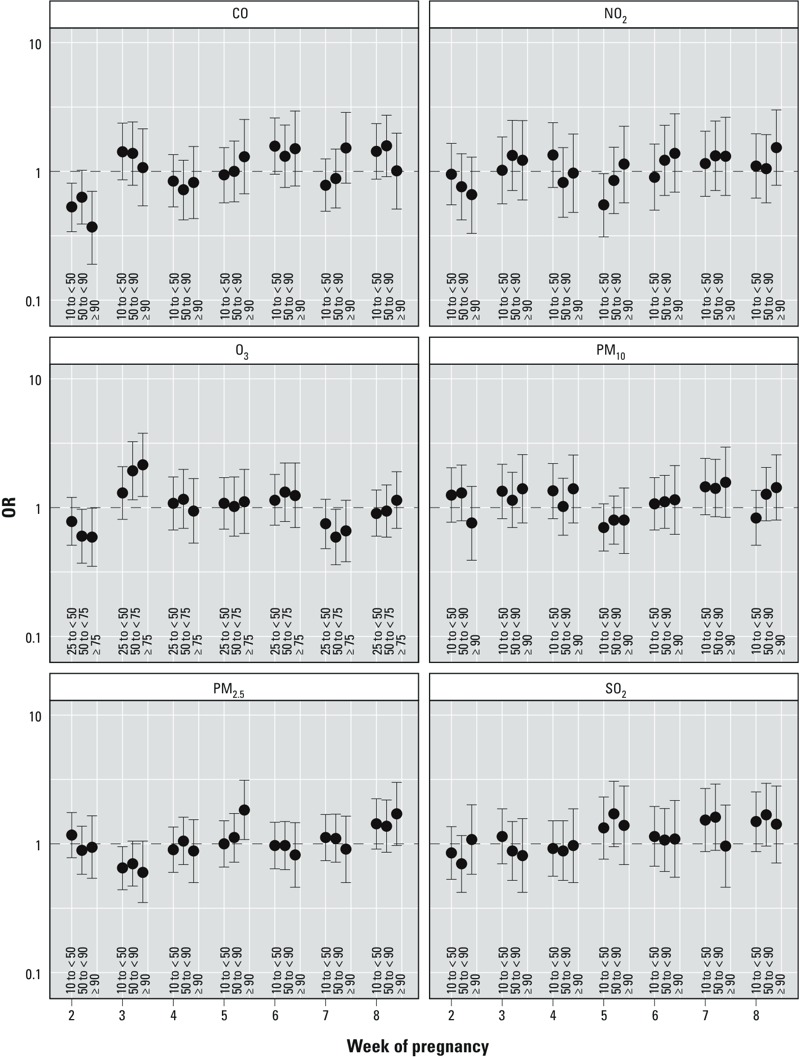

Exposure assigned as 1-week average of daily maxima or 24-hr measurements. Full results for the weekly exposure analyses are provided in Supplemental Material, Table S4. PVS showed variability within the window of cardiac development for multiple pollutants (Figure 2). Both CO and O3 had individual weeks where the estimates were larger in magnitude than estimates obtained using the summary exposure and where the other weeks were closer to null, suggesting a period of greater susceptibility (CO, week 2: 90th/10th centile comparison: OR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.19, 0.7; O3, week 3: 75th/25th centile comparison: OR = 2.15; 95% CI: 1.22, 3.78). PM2.5 had no association with PVS when a summary measure of exposure was used, but there was an almost doubling of odds in week 5 when comparing women with exposure greater than the 90th centile to women with exposure less than the 10th centile (OR = 1.83; 95% CI: 1.08, 3.12) that was similarly observed in week 8.

Figure 2.

Estimated adjusted ORs and 95% CIs of pulmonary valve stenosis for categorical measures of 1-week averages of daily maxima/24-hr measures of criteria air pollutants, plotted for weeks 2–8 of pregnancy, National Birth Defects Prevention Study 1997–2006 (for PM2.5, 1999–2006). ORs were estimated from hierarchical regression models. First stage was a polytomous logistic model, adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity, age, educational attainment, household income, maternal smoking status and alcohol consumption during early pregnancy, nativity, and site-specific heart defect ratio. Second stage was a linear model with indicator variables for defect, defect grouping, and level of exposure. For all pollutants except O3, the three categories of exposure are as follows: 10th centile to < 50th centile, 50th centile to < 90th centile, and ≥ 90th centile, with the referent level being < 10th centile among controls. For O3, the three categories of exposure were 25th to < 50th centile, 50th centile to < 75th centile, and ≥ 75th centile, with the referent grouping being < 25th centile. Pollutant levels that define the category cut points are provided in Table 2. See Supplemental Material, Table S4, for corresponding numeric data.

Week 2 of pregnancy was another potential window of susceptibility to PM2.5. Women having a child with TOF had almost twice the odds of being above the 90th centile versus below the 10th centile for PM2.5 exposure in week 2 of pregnancy as controls (OR = 1.96; 95% CI: 1.11, 3.46), whereas women with a baby with atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) had more than three times the odds (OR = 3.43; 95% CI: 1.36, 8.66). Women with offspring with defects within the septal grouping were less likely to have higher PM2.5 exposure during this time (90th/10th centile comparison OR = 0.6; 95% CI: 0.4, 0.9). Using the summary exposure revealed a slightly elevated OR for VSDpm among women with SO2 exposure greater than the 90th centile (OR = 1.48; 95% CI: 0.91, 2.42), but weekly analysis revealed this association was limited to week 3, and the magnitude increased (VSDpm OR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.1, 3.56). During other weeks, the ORs for VSDpm comparing the 90th centile to the 10th centile ranged from 0.77 to 1.13.

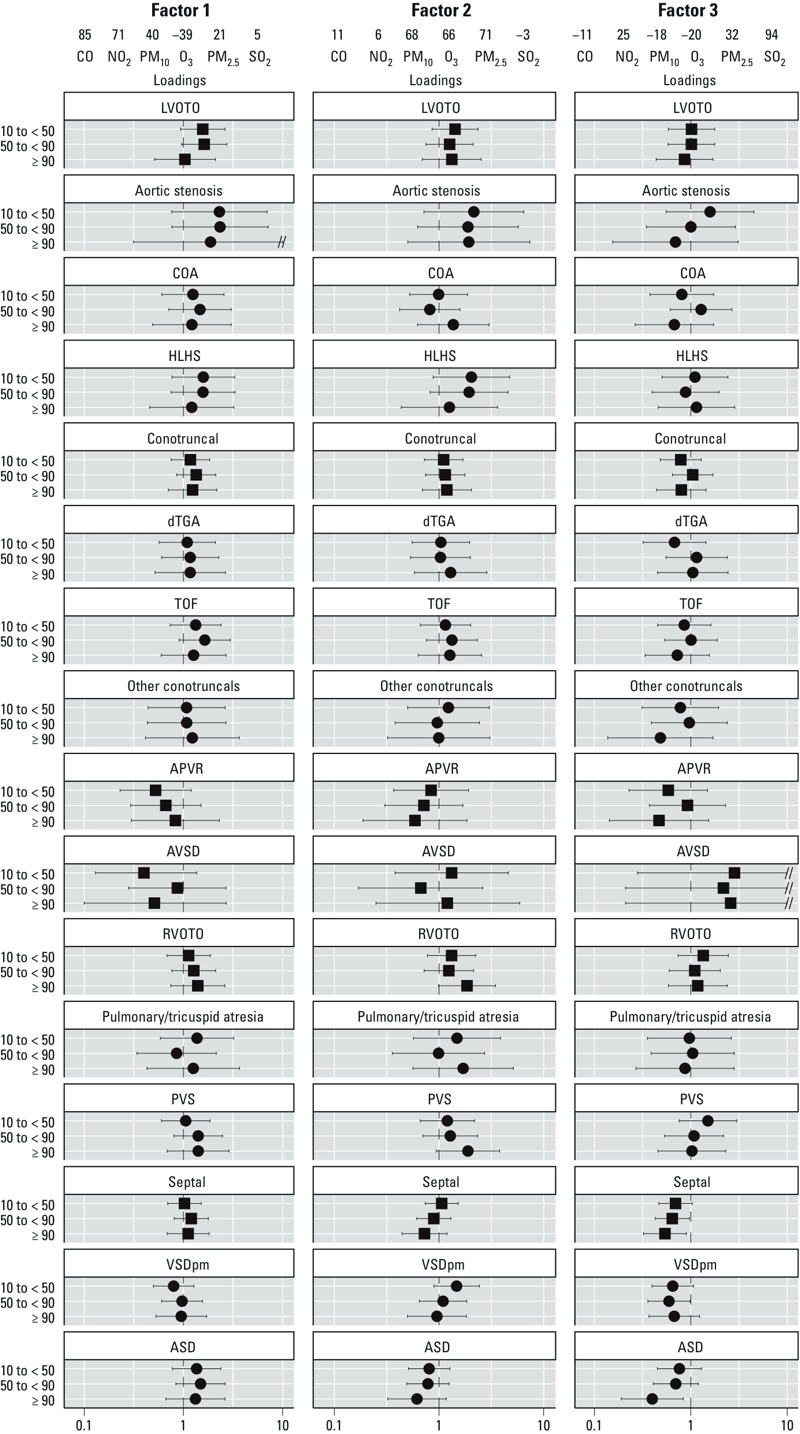

PCA. Only 26% of the geocoded population (n = 2,914) had exposure data for all pollutants. These women were primarily from the Massachusetts and Atlanta, Georgia, sites, nonsmokers, and living in a higher-income household. African-American women made up a slightly larger percentage of these women when compared with the individual pollutant populations (data not shown). With this subsample, three factors emerged from the PCA. The factor that explained the largest amount of variance was loaded primarily by CO and NO2, gaseous pollutants likely related to direct emissions from local sources such as motor vehicle traffic. The second factor, driven by PM10, PM2.5, and O3, represents local particulates and secondary pollutant generation. The third factor was loaded by SO2 and most likely represents emissions from regional sources, potentially from coal combustion.

Findings were less precise than single-pollutant models due to the reduced sample size (Figure 3; see also Supplemental Material, Table S5, for corresponding numeric data). We observed ORs > 1 for the NO2 loaded factor (factor 1) and LVOTO defects, particularly aortic stenosis and HLHS and the PM10/PM2.5/O3 factor (factor 2) and HLHS, although these associations were diminished or absent at the highest exposure level. The ORs for the NO2 loaded factor (factor 1) and PVS were attenuated when compared with results from the NO2 single-pollutant model. We also observed monotonically increasing ORs between PVS and exposure to the PM10/PM2.5/O3 factor (factor 2), which was not observed in any of the single-pollutant models for those individual pollutants. Within the multipollutant context, the SO2 loaded factor (factor 3) was inversely associated with the septal defect grouping, as well as both ASD and VSDpm. In the single-pollutant models, we observed a slight inverse association with ASD, but a slightly positive association with VSDpm. The slightly increased ORs for SO2 exposure and PVS and HLHS observed in the single-pollutant model were not observed in the results from the PCA.

Figure 3.

Estimated adjusted ORs and 95% CIs between CHDs and pollutant factors identified through PCA within the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1999–2006. Abbreviations: APVR, anomalous pulmonary venous return; ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; COA, coarctation of the aorta; dTGA, transposition of the great arteries; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstructions; PVS, pulmonary valve stenosis; RVOTO, right ventricular outflow tract obstructions; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSDpm, perimembranous ventricular septal defects. Other conotruncal category includes common truncus, IAA‑type B and -NOS, double outlet right ventricle defects, and conoventricular septal defects. A double slash (//) indicates truncation of the results. Squares indicate defect groupings; circles indicate individual defects. Defect groupings include all individual defects listed underneath with the following additions: LVOTO, IAA‑type A; APVR, total and partial APVR; RVOTO, Ebstein’s anomaly. Those defects could not be analyzed within the hierarchical regression due to limited sample size. Loadings represent the relative weight of each of the original pollutant variables used to obtain the value of the computed factor. ORs were estimated from hierarchical regression models. First stage was a polytomous logistic model, adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity, age educational attainment, household income, maternal smoking status and alcohol consumption during early pregnancy, nativity, and site-specific heart defect ratio. Second stage was a linear model with indicator variables for defect, defect grouping, and level of exposure. For all factors, the three categories of exposure are as follows: 10th centile to < 50th centile, 50th centile to < 90th centile, and ≥ 90th centile, with the referent level being < 10th centile among controls. Pollutant levels which define the category cutpoints are provided in Table 2. See Supplemental Material, Table S5, for corresponding numeric data.

The sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of model specification did not show a material difference in results obtained when using different values of second-stage variance or varying factors defining the predicted values (data not shown). To explore our choice of a 50-km buffer size, we restricted our analyses to women who lived within 10 km of a monitor and used the same exposure categories and model construction described previously (see Supplemental Material, Table S6). Sample size was reduced to 27.5–48.1% (n = 1,683–3,709) of the original study population depending on pollutant. Despite the greater imprecision, many estimates remained similar: For example, the observed positive associations in the full population between higher exposure to NO2 and LVOTO (OR = 1.53; 95% CI: 0.98, 2.39) and RVOTO defects (OR = 2.22; 95% CI: 1.40, 3.52) were only slightly changed when restricting to the population within 10 km of an air monitor (LVOTO OR = 1.44; 95% CI: 0.58, 3.61; RVOTO OR = 2.33; 95% CI: 0.75, 7.22). The inverse association between PM2.5 exposure and the septal defect grouping also remained consistent after limiting the population. Although most null estimates remained so, some null estimates increased in magnitude, suggesting a potential for an association in the restricted population. For example, the OR for LVOTO defects comparing the highest and lowest quartiles of O3 exposure was 0.94 in the population within 50 km of a monitor (95% CI: 0.73, 1.22) but was 1.62 (95% CI: 0.84, 3.13) in the population within 10 km of a monitor. A similar increase in magnitude was observed for PM2.5 and LVOTO defects. The estimates related to SO2 exposure changed the most, with multiple ORs > 1 in the population of women living within 50 km of a monitor crossing over the null when the population was restricted to those within 10 km.

Discussion

We found that the odds of several CHDs were higher among women with greater exposures to criteria air pollutants. We observed monotonically increasing associations between NO2 exposure and both COA and PVS. We also observed that women with a child with HLHS were two times as likely to live in an area with the highest level of PM2.5 exposure as women whose child did not have a CHD, although a similar association was not seen for women in the middle-high exposure level. Using 1-week averages, we observed temporal variability in odds of certain CHDs within the window of cardiac development. Marked by positive or negative associations in individual weeks with near null relationships in the other weeks, this pattern was observed for AVSD, PVS, TOF, and the septal defect grouping when looking across weeks of PM2.5 exposure, PVS when examining weeks of O3 exposure, and VSDpm across weeks of SO2 exposure, although we did not observe a consistent week of greater susceptibility across different defects and pollutants.

Our findings suggest preliminary evidence that there may be periods of higher or lower susceptibility within the window of cardiac development. Embryological evidence indicates the timing of specific stages of cardiac development, beginning with the migration of cells to form the endocardial tubes and culminating with the septation of the ventricles and outflow tracts in weeks 7 and 8 of development (Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 2005). However, there is experimental research showing that triggering oxidative stress in diabetic mice can result in apoptosis among migrating neural crest cells, which later results in outflow tract defects (Morgan et al. 2008), and that neural crest cells enable the endocardial cushions to form the cardiac valves (Jain et al. 2011). This suggests it is possible that pollutant-induced oxidative stress in earlier weeks of development can trigger similar disruptions in neural crest cells that later affect development of cardiac structures, and that windows of susceptibility to environmental insults may not always directly coincide with the established stages of fetal heart development. Further research is needed to explore how timing of exposure within this narrow window may affect the risk of CHDs or whether the fluctuations in results we observed when examining weekly exposure are attributable to random noise.

Findings from the PCA-based analysis continued to show greater odds of certain CHDs with increasing pollutant exposure. The inverse association between SO2 and ASDs observed in the single-pollutant analysis was also observed in the PCA-based analysis. However, the positive associations between exposure to SO2 and PVS and VSDpm found in the single-pollutant analysis were not observed when the SO2-loaded component was examined simultaneously with other pollutant components. These differences could be attributable to co-pollutants not accounted for in the single-pollutant models or to different demographics of the subsample of women with data on all pollutants. We often observed a decrease in odds at the highest ambient level, compared with the median-high group, in both the PCA-based analyses and single-pollutant models. Ritz (2010) has previously suggested that this nonlinearity could be attributable to differential pregnancy loss at very high exposures. It is also possible that women who live in highly polluted areas spend less time outdoors, causing exposure to be lower than what the ambient level suggests.

Our findings were consistent with the primary associations reported in the previous meta-analysis (Vrijheid et al. 2011): NO2 and TOF, and SO2 and COA, as well as an association between greater NO2 exposure and COA, which was suggested in the meta-analysis, although not robust to the exclusion of the largest study. We observed some of the findings from individual studies that were not identified in the meta-analysis; for example, we observed the association between SO2 and VSDs reported by Gilboa et al. (2005) and the inverse association between PM2.5 and ASDs reported by Padula et al. (2013), but not other findings such as the inverse associations between SO2 and conotruncal defects reported by both Gilboa et al. (2005) and Hansen et al. (2009). Differences in findings between studies could be attributable to spatial variation in source of pollutants and composition of particulates, as well as differences in case ascertainment and exposure assignment (Vrijheid et al. 2011).

This study has a number of strengths, including the large geographic scope and sample size of the NBDPS that allows analysis of systematically classified individual CHDs, while limiting analyses to simple, isolated defects to avoid heterogeneity from etiologies of multiple defects. Including live births, fetal deaths, and elective terminations prevents incomplete case ascertainment, and collecting complete residential history avoids misclassification of exposure due to using residence at delivery (Miller et al. 2010). We explored timing of exposure within the critical window of heart development and used daily maxima so as not to smooth over potentially relevant variability in exposure. Using hierarchical regression allowed us to improve estimation and partially address the issue of multiple testing, and using PCA allowed us to assess the relationship between air pollutants and CHDs in a multipollutant context.

Assigning exposure using ambient concentrations of pollutants at their residential location does not account for time spent indoors and pollutant concentrations at other relevant locations. This exposure misclassification could influence our effect estimates if there are differences in these factors between cases and controls—for example, if mothers of case offspring had more difficult pregnancies, limiting their outdoor movement. There is also the potential for exposure misclassification by assigning exposure using the nearest monitor. Previous research suggests that even when limiting to the closest monitor within 10 km, the 10th–90th percentile exposure contrast is larger for nearest monitor analyses than for other forms of exposure assessment (Marshall et al. 2008). This would have less of an impact on our study where we categorized exposure based on the distribution, rather than performing contrasts on a fixed-unit change in exposure. In simulation analyses of air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events, Kim et al. (2009) found that hazard ratios derived using nearest-monitor exposures were more biased than those derived using exposures obtained from kriging, particularly as the monitoring network became sparse. These biases tended to be toward the null, suggesting that our estimates may underestimate the true relationship between air pollutants and CHDs.

The NBDPS had a response slightly lower than 70% and is subject to potential selection bias based on who agrees to participate. Additionally, there is the potential for selection bias if the factors that contribute to women living near a pollutant monitor are also associated with pollutant exposure and CHDs. We did not observe strong associations between maternal demographic factors that could influence residential location and the presence of CHDs within our full population. However, our results may not be generalizable to populations who live > 50 km from an air monitor. Because air pollutants vary spatially, study center may confound the relationship between air pollutants and CHDs through pathways such as differences in case ascertainment and resident sociodemographics. We controlled for a marker of case ascertainment in our model, but we may not have completely accounted for differences in case ascertainment across sites, and residual confounding due to unmeasured, spatially varying factors including other environmental exposures could affect our results. Our PCA analysis was based on a highly select population who live near multiple pollutant monitors and may not be generalizable to the larger population.

We conducted many analytic contrasts, and although hierarchical regression partially addresses multiple comparisons, it is possible that some of our findings are attributable to chance. We used hierarchical regression because other methods that deal with multiple comparisons do not account for the association between estimates that occurs when assessing weekly exposures simultaneously. It is possible that certain subgroups in the population may be more vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution due to their diet, genetics, co-exposures, or other factors not addressed in this study. If this is the case, we may have underestimated or missed an association between air pollutants and CHDs that would be seen only in that select population.

In this study, we observed increased odds of several CHDs with greater pollutant exposure. Some of these positive associations were observed only during specific weeks within the window of cardiac development, suggesting that accounting for temporal variability in pollutant concentrations and developmental susceptibility can improve effect estimation. Future research should focus on further exploration of temporal windows of susceptibility and examining the risk of CHDs within a multipollutant context, in order to gain understanding of the contribution of the different air pollutants.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participating study centers, including the California Department of Public Health, Maternal Child and Adolescent Health Division, for providing data on study subjects for the National Birth Defects Prevention Study.

Footnotes

This study was supported in part through cooperative agreements under Program Announcement 02081 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to the centers participating in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study including cooperative agreement U50CCU422096. Additionally, this research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30ES010126 and T32ES007018) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (T32HD052468).

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the California Department of Public Health, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

- Agay-Shay K, Friger M, Linn S, Peled A, Amitai Y, Peretz C. Air pollution and congenital heart defects. Environ Res. 2013;124:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botto LD, Lin AE, Riehle-Colarusso T, Malik S, Correa A. Seeking causes: classifying and evaluating congenital heart defects in etiologic studies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79(10):714–727. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa A, Gilboa SM, Besser LM, Botto LD, Moore CA, Hobbs CA, et al. Diabetes mellitus and birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):e231–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand P, Rankin J, Rushton S, Pless-Mulloli T. Ambient air pollution and congenital heart disease: a register-based study. Environ Res. 2011a;111(3):435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand P, Rankin J, Rushton S, Pless-Mulloli T. Association between maternal exposure to ambient air pollution and congenital heart disease: a register-based spatiotemporal analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2011b;173(2):171–182. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolk H, Armstrong B, Lachowycz K, Vrijheid M, Rankin J, Abramsky L, et al. Ambient air pollution and risk of congenital anomalies in England, 1991–1999. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(4):223–227. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.045997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolk H, Vrijheid M. The impact of environmental pollution on congenital anomalies. Br Med Bull. 2003;68:25–45. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa SM, Mendola P, Olshan AF, Langlois PH, Savitz DA, Loomis D, et al. Relation between ambient air quality and selected birth defects, seven county study, Texas, 1997–2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):238–252. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Bartelings MM, Deruiter MC, Poelmann RE.2005Basics of cardiac development for the understanding of congenital heart malformations. Pediatr Res 57: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. A semi-Bayes approach to the analysis of correlated multiple associations, with an application to an occupational cancer-mortality study. Stat Med. 1992;11(2):219–230. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen CA, Barnett AG, Jalaludin BB, Morgan GG.2009Ambient air pollution and birth defects in Brisbane, Australia. PLoS One 44e5408; 10.1371/journal.pone.0005408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1994. A Step-by-Step Approach to Using SAS® for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze G, Schemper M.2002A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med 2116): 2409–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Engleka KA, Rentschler SL, Manderfield LJ, Li L, Yuan L, et al. Cardiac neural crest orchestrates remodeling and functional maturation of mouse semilunar valves. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(1):422–430. doi: 10.1172/JCI44244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Sheppard L, Kim H. Health effects of long-term air pollution: influence of exposure prediction methods. Epidemiology. 2009;20(3):442–450. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31819e4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclure M, Greenland S. Tests for trend and dose response: misinterpretations and alternatives. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(1):96–104. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JD, Nethery E, Brauer M. Within-urban variability in ambient air pollution: Comparison of estimation methods. Atmos Environ. 2008;42(6):1359–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR, Perry LW, Ferencz C. Increased prevalence of ventricular septal defect: epidemic or improved diagnosis. Pediatrics. 1989;83(2):200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Siffel C, Correa A. Residential mobility during pregnancy: patterns and correlates. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(4):625–634. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0492-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SC, Relaix F, Sandell LL, Loeken MR. Oxidative stress during diabetic pregnancy disrupts cardiac neural crest migration and causes outflow tract defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82(6):453–463. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1998. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. NIH Publication no. 98-4083. [Google Scholar]

- Padula AM, Tager IB, Carmichael SL, Hammond SK, Yang W, Lurmann F, et al. Ambient air pollution and traffic exposures and congenital heart defects in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27(4):329–339. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin J, Chadwick T, Natarajan M, Howel D, Pearce MS, Pless-Mulloli T. Maternal exposure to ambient air pollutants and risk of congenital anomalies. Environ Res. 2009;109(2):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz B. Air pollution and congenital anomalies. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(4):221–222. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.051201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz B, Yu F, Fruin S, Chapa G, Shaw GM, Harris JA. Ambient air pollution and risk of birth defects in Southern California. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(1):17–25. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland MJ, Klein M, Correa A, Reller MD, Mahle WT, Riehle-Colarusso TJ, et al. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular malformations in Atlanta, Georgia, 1986–2003. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(8):1004–1014. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). 2012. Available: http://epa.gov/air/criteria.html [accessed 11 November 2013]

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). Technology Transfer Network (TTN) Air Quality System (AQS) Data Mart. 2013. Available: http://www.epa.gov/ttn/airs/aqsdatamart [accessed 11 November 2013]

- van den Hooven EH, de Kluizenaar Y, Pierik FH, Hofman A, van Ratingen SW, Zandveld PY, et al. 2012Chronic air pollution exposure during pregnancy and maternal and fetal C-reactive protein levels: the Generation R Study. Environ Health Perspect 120746–751.; 10.1289/ehp.1104345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijheid M, Martinez D, Manzanares S, Dadvand P, Schembari A, Rankin J, et al. 2011Ambient air pollution and risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect 119598–606.; 10.1289/ehp.1002946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte JS, Greenland S, Kim LL. Software for hierarchical modeling of epidemiologic data. Epidemiology. 1998;9(5):563–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon PW, Rasmussen SA, Lynberg MC, Moore CA, Anderka M, Carmichael SL, et al. The National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(suppl 1):32–40. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.