Abstract

Choroidal osteomas are rare benign ossifying tumors that appear as irregular slightly elevated, yellow-white, juxtapapillary, choroidal mass with well-defined geographic borders, depigmentation of the overlying pigment epithelium; and with multiple small vascular networks on the tumor surface. Visual loss results from three mechanisms: Atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium overlying a decalcified osteoma; serous retinal detachment over the osteoma from decompensated retinal pigment epithelium, and most commonly from choroidal neovascularization. Recent evidence points to the beneficial effects of intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor antagonists in improving visual acuity in serous retinal detachment with or without choroidal neovascularization.

Keywords: Argon Laser, Choroidal Osteoma, Intravitreal Bevacizumab, Intravitreal Ranibizumab, Photodynamic Therapy

INTRODUCTION

Choroidal osteoma is a rare benign ossifying tumor characterized by mature cancellous bone involving the choroid. It is an often unilateral condition that affects the juxtapapillary and macular areas of young females. Ever since the first case was presented at the meeting of the Verhoeff Society in 1975 and reported by Gass et al., multiple case reports and case series were published.1,2 But many aspects of this disease regarding its etiology, pathophysiology and treatment remain unidentified.

METHOD OF LITERATURE SEARCH

The literature search was performed in PubMed and Google Scholar. The following search words were used: Choroidal osteoma. No limitations were made. Reviews were studied to create an overview and guidance for further search. The articles reviewed were those published in English, French and German although no language preference was intended. The abstracts in English were read for articles of relevance in other languages.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Choroidal osteoma is a rare condition. The largest case series in the literature includes 61 patients over a 26 year-span of ocular oncology practice in a major tertiary care center.3 Its precise frequency remains unknown. It occurs in all races but predominantly affects young adults in their early twenties with a large range from few months old to late sixties. It has a predilection for women and is unilateral in around 80 percent of cases.3,4,5 A few familial cases were reported6,7,8,9 but their overall proportion is small.4

ETIOLOGY

The exact etiology of choroidal osteoma is unknown. Theories on its origin include congenital causes,7 osseous choristoma,2 inflammatory conditions10,11 and endocrine disorders.6,12 It was not found to be associated with any systemic or ocular condition. Sporadic reports have linked choroidal osteomas to Stargardt's maculopathy,13 polypoidal choroidal maculopathy,14 pregnancy,12,15 recurrent orbital inflammatory pseudotumor,10 intraocular inflammation11 and histiocytosis X16 Also, no established risk factors could be identified despite early hints relating it to trauma.6,17 Despite earlier suggestions, there has been found no association between choroidal osteoma and any abnormality in blood chemistries such as calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, complete blood count and urinalysis.5,6]

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

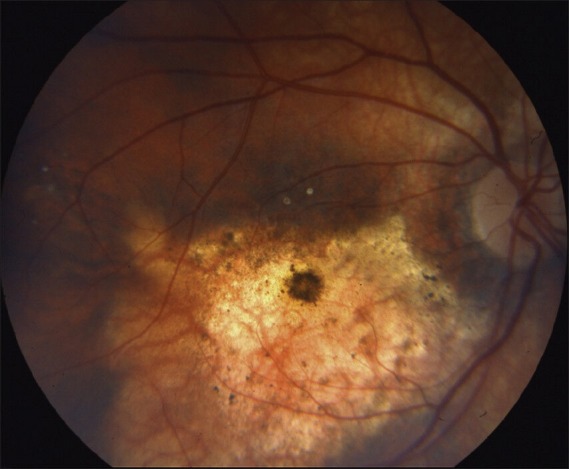

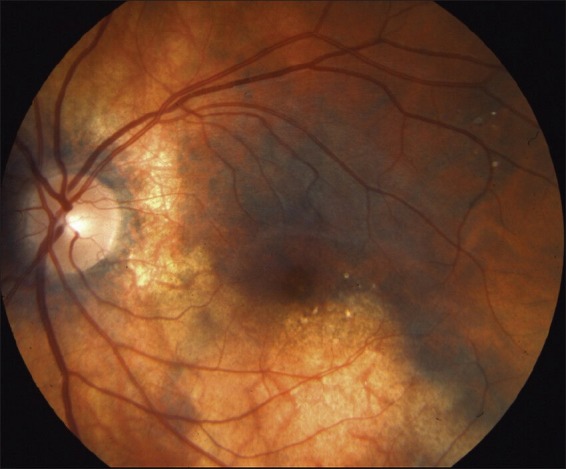

Choroidal osteoma appears a deep, orange-yellow lesion with distinct geographic or scalloped borders [Figures 1 and 2] and branching vessels on the surface of the tumor. The lesion color relates to the level of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) depigmentation.1 Early stages choroidal osteomas tend to have an orange-red color, whereas in later stages they have a yellowish tint from RPE depigmentation.18

Figure 1.

Right fundus photograph showing a posterior pole choroidal osteoma involving the macula with overlying atrophy of the retina and choroid (Courtesy of Dr Sami Uwaydat, University of Arkansas)

Figure 2.

Left fundus photograph showing a peripapillary and inferior arcade choroidal osteoma sparing the fovea. Patient had bilateral choroidal osteomas with the right fundus depicted in Figure 1 (Courtesy of Dr Sami Uwaydat, University of Arkansas)

Histopathology illustrates dense bony trabeculae with marrow spaces traversed by pathognomonic dilated thin-walled blood vessels, termed spider or feeder vessels. These vessels seem to connect the choriocapillaris to the larger choroidal vessels.1,2,18]

Tumor growth occurred in 41-64% of cases followed for a period of 10 years.3,4,6,11,19,20,21 Except for infrequent instances of rapid growth,22 most choroidal osteomas have a slow random growth, on any of the non-calcified margins, with an increase in mean basal diameter of around 0.37 mm per year.3

Tumor decalcification and resolution, originally described by Trimble in 1988, occurs in around50 percent of cases and is characterized by thin, atrophic, yellow-gray region with overlying RPE and choriocapillaris atrophy. It is associated with poor long-term visual acuity3,23,24 when the decalcification is located under the fovea due to overlying photoreceptor loss.25 Decalcification can be spontaneous26 or triggered by either laser photocoagulation19,23,27 or photodynamic therapy (PDT)28 that probably induce osteoclastic activity in the lesion. Most recently, optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging has demonstrated how decalcification of an osteoma occupying the full choroidal thickness lead to the apposition of the overlying retina to the underlying sclera.29

Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) are very common in choroidal osteomas. Tumors with overlying hemorrhage and irregular surface are at a greater risk of developing CNV.3 Overall, CNV occurred in 31-47 percent of cases,3,4 with a suggested association with decalcification due to the disruption of the RPE and Bruch membrane.3 Shields hypothesized that this RPE layer disruption allows growth of underlying choroidal new vessels.5 Alternatively, Foster theorized that neovascular membranes are extensions of the osteoma itself.30 In support of his hypothesis, osteoclasts were detected in a surgically removed neovascular membrane, and recent OCT imaging is showing neovascular membranes emanating from the central portion of the osteoma.29

Choroidal osteomas are also known to be associated with subretinal fluid, hemorrhages and serous retinal detachment. Serous retinal detachment occurs in choroidal osteoma frequently in the absence of CNV. In fact, only about23 percent of eyes with subretinal fluid have concomitant CNV.4 It is speculated to be the result of multiple pinpoint RPE leakage sites over the osteoma as detected by fluorescein angiography.31 Alternatively, atrophy of the RPE and Bruch membrane is thought to decrease their capacity to remove subretinal fluid emanating from the disrupted outer blood-retinal barrier.32

PROGNOSIS

On long-term follow up of choroidal osteomas (up to 10 years), around 64 percent of eyes with subretinal fluid resolved spontaneously.4 The remaining eyes with non-resolving subretinal fluid had a poor visual outcome.4 The visual prognosis is influenced by the tumor location, decalcification status, overlying RPE atrophy, presence of CNV, persistence of subretinal fluid and occurrence of subretinal hemorrhages. Overall, the estimated 10-year probability of losing visual acuity to the level of 6/60 (20/200) and less is around 56-58 percent.3,4 In an analysis of 74 eyes with choroidal osteoma, good visual acuity (20/20-20/40) was found in 24 of 30 eyes (80%) without foveolar involvement of tumor compared with 20 of 44 eyes (45%) with foveolar involvement.3

DIAGNOSIS

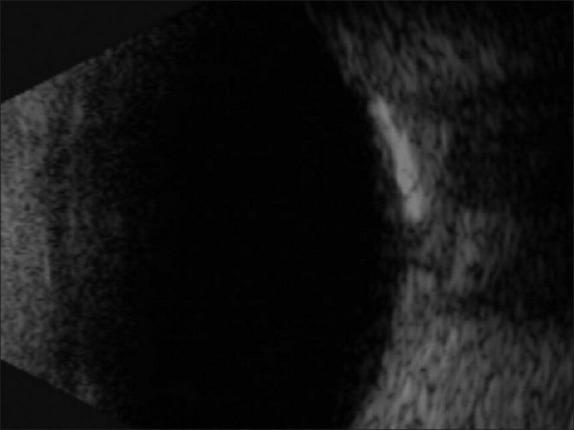

The diagnosis of choroidal osteoma is mainly clinical. Patients usually present with symptoms of blurred vision, metamorphopsia, photophobia or visual field defects. Between 8 and 30 percent of cases remain asymptomatic.3,4 The tumor appears as an orange-yellow distinct lesion [Figures 1–4]. Ancillary diagnostic tests include fluorescein angiography, auto fluorescence, ultrasound imaging (A or B-scan), computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Due to the presence of calcified components, choroidal osteomas have high acoustic reflectivity and shadowing on ultrasonography: High intensity echo spike on A scan imaging. On B scan imaging, the osteoma appears as a slightly elevated choroidal mass [Figure 5]. It appears dense at higher sensitivity, and remains highly reflective at lower scanning sensitivities on B scan ultrasound. A characteristic shadowing or sound attenuation can be seen posterior to the lesion that gives it the appearance of a pseudo-optic nerve.5,33]

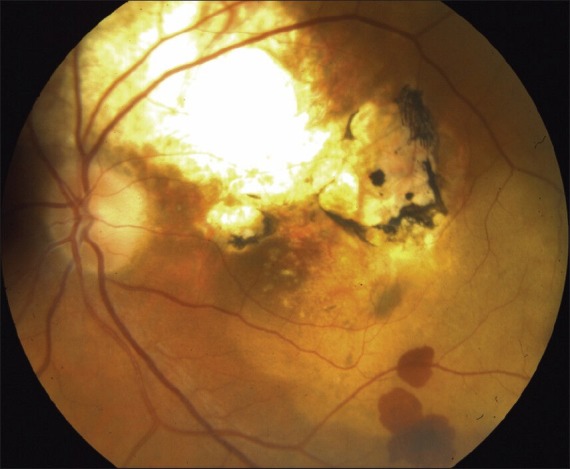

Figure 4.

Left peripapillary extrafoveal osteoma of the choroid measures 3 by 2 disc diameters and is associated with subfoveal CNV that responded to 2 consecutive intravitreal bevacizumab injections with visual improvement over one year of follow-up. B-scan, OCT and fluorescein angiography transits are shown in Figures 7-9 (Courtesy of Dr Eman Al Kahtani, King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital)

Figure 5.

B-scan demonstrates focal subretinal calcification from 2:00 to 3:00 o'clock next to the optic disc. (Courtesy of Dr Eman Al Kahtani, King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital)

A hyperdense choroidal plaque with the same density as bone typically appears at the level of the tumor on CT scan. MRI images show a hyperintense signal with gadolinium-DPTA enhancement on T1-weighted images, and a relative low intensity on T2-weighted images.34

On fluorescein angiography, choroidal osteoma have early patchy hyperfluorescent choroidal filling pattern with late diffuse staining [Figure 6]. Fluorescein angiography is also helpful in detecting RPE atrophy, CNV formation or the characteristic spider vessels.3,28,29,32,35]

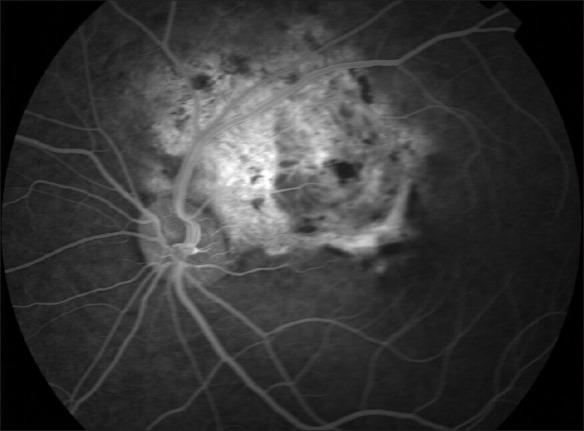

Figure 6.

Fluorescein angiography 35-second transit reveals dye leakage in the foveal region (CNV) and dye staining in the area of chronic RPE decompensation overlying the choroidal osteoma at 1 o'clock near the peripapillary area (Courtesy of Dr Eman Al Kahtani, King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital)

On fundus auto-fluorescence imaging, various patterns have been detected depending on the level of decalcification, lipofuscin accumulation, outer retina and RPE atrophy. Auto-fluorescence increased in metabolically stressed outer retina and RPE, and was absent in atrophic or dysfunctional RPE. Sisk thus proposed abnormal foveal auto-fluorescence as a marker for poor visual prognosis.34 Recently, calcified choroidal osteomas were shown to have relatively well preserved fluorescence on blue-light autofluorescence; whereas the decalcified areas had reduced overall fluorescence.29

On indocyanine green angiography, choroidal osteomas show early hypo-fluorescence, followed by fine diffuse multifocal fluorescence that becomes confluent in late transits.36

Since the introduction of the OCT technology, choroidal osteomas have been described using different types of OCT instruments . Using the time-domain optical coherence tomography (TD-OCT), irregular plate-like high-signal intensity areas were detected in the region of the tumor with multiple tracks of high refractivity posterior to the tumor.33 These lines of high refractivity posterior to the tumor were later postulated to correspond to the tumor-choroid interface, or to displacement of choroidal melanocytes by the tumor toward the choriocapillaris and inner scleral lamella.29 Using the spectral-domain SD-OCT and Fourier domain FD-OCT with higher resolution and penetration, a wide range of tumor reflectivity patterns was demonstrated from hypo-reflective to iso-reflective to hyper-reflective.37,38 Furthermore, a latticework reflective pattern in calcified tumor regions that has similitude to the original osteoma spongy bone histopathology was illustrated.29,37 The overlying retina was noticed to be preserved in architecture over the calcified areas while photoreceptor loss was noted over the decalcified areas.25,29,33,39]

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Choroidal osteomas can be easily confused with other entities with similar presentations. One study estimated that up to 90 percent of eye care practitioners initially missed the diagnosis of choroidal osteoma.40 In fact, choroidal osteomas are included in the large differential diagnosis of ocular tumors and ocular calcification. These include amelanotic choroidal melanoma, amelanotic choroidal nevus, metastatic choroidal carcinoma, circumscribed choroidal hemangioma, disciform macular degeneration, posterior scleritis, idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification, choroidal cartilage, leukemia, retinoblastoma and others [Table 1].

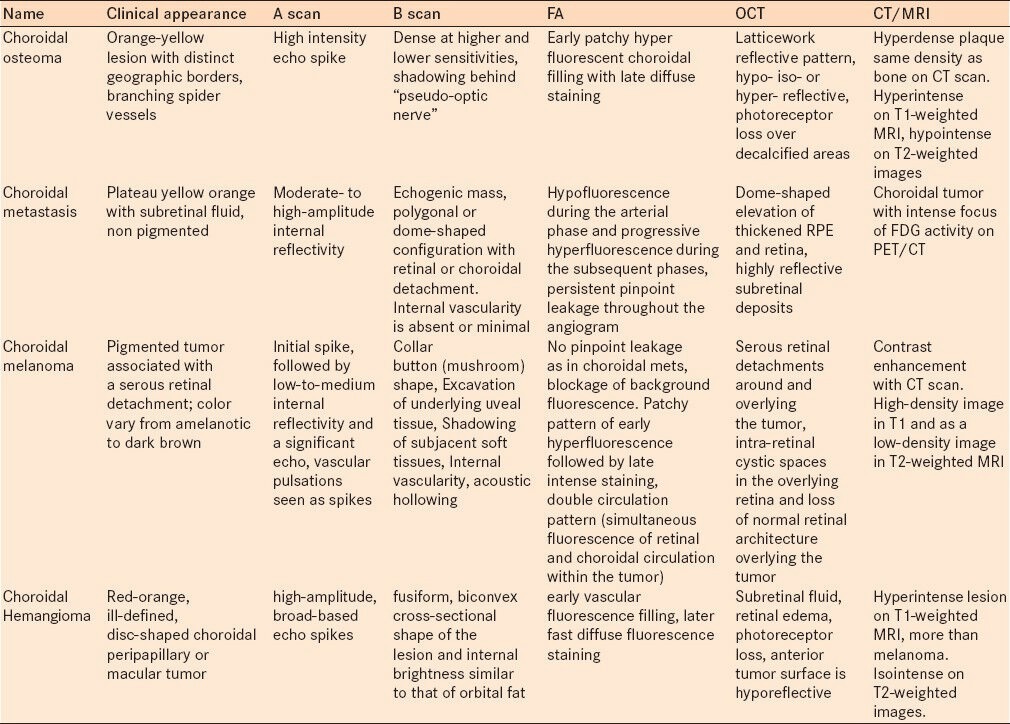

Table 1.

Differentiating clinical manifestations of various choroidal lesions (osteoma, melanoma, hemangioma and metastatic lesions)

Amelanotic choroidal melanomas are usually more elevated and have less defined margins. Also lacking distinct margins are the amelanotic choroidal nevi and metastatic carcinomas, with the latter usually associated with a large serous retinal detachment. Moreover, idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification is rather multifocal in pattern and is more likely to be bilateral compared to choroidal osteoma.3,41]

TREATMENT

There is no standard of treatment for choroidal osteomas, but therapies are directed for complications arising from choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and subretinal fluid.

Osteomas with CNV

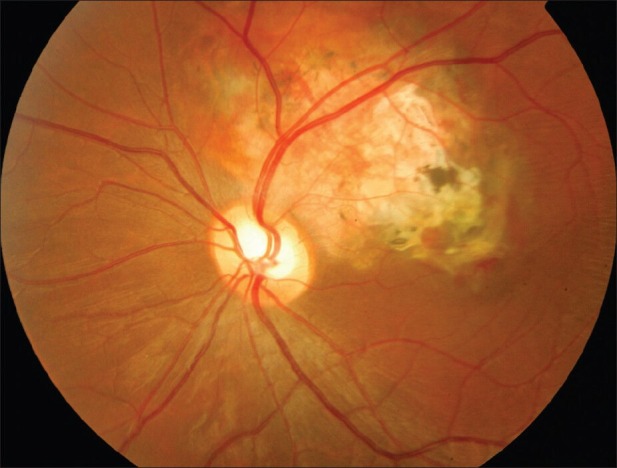

Various treatment modalities have been tried for CNV in choroidal osteoma. Surgical removal of the CNV did not yield encouraging visual results, with 20/160 four months and 20/320 four years after surgery.30 Argon [Figure 3] and krypton laser photocoagulation have been tried with variable results.4,5,19,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 This mode of treatment is limited to extrafoveal lesions. The largest series noted around45 percent success rate in treating extrafoveal CNV which is less than expected in age-related macular degeneration-related CNV.4 The degeneration of the RPE layer overlying a largely non-pigmented choroidal osteoma was postulated to contribute to the poor outcome of thermal laser photocoagulation.4,19]

Figure 3.

Fundus photograph of the left eye with superior peripapillary and macular choroidal osteoma with associated CNV. Before the anti-VEGF era, this patient had multiple argon laser treatments with recurrence of the membranes (Courtesy of Dr Sami Uwaydat, University of Arkansas)

For subfoveal CNV, transpupillary thermotherapy (TTT) has been tried on a small number of patients in a couple of reports with good results. Resolution of CNV was observed in both cases. One eye had improved visual acuity to 6/18 after a single session50 and the other eye maintained visual acuity of 6/60 following multiple laser sessions.51

Photodynamic therapy (PDT), a modality less dependent on the RPE layer, has been tried with encouraging results in both extrafoveal28,52 and subfoveal CNV.53 PDT was efficient in the short term in closing the CNV in such cases, but might require multiple sessions and can decrease the final visual acuity.54

PDT and laser photocoagulation can, as previously mentioned, cause focal decalcification of the tumor.3,19,23,27 Although a favorable outcome in preventing the growth of extrafoveal tumors into the fovea,4,28 decalcification is conversely associated with overlying retinal damage.25,29,33,39 Thus it is speculated that PDT might be visually detrimental particularly in subfoveal tumors.28

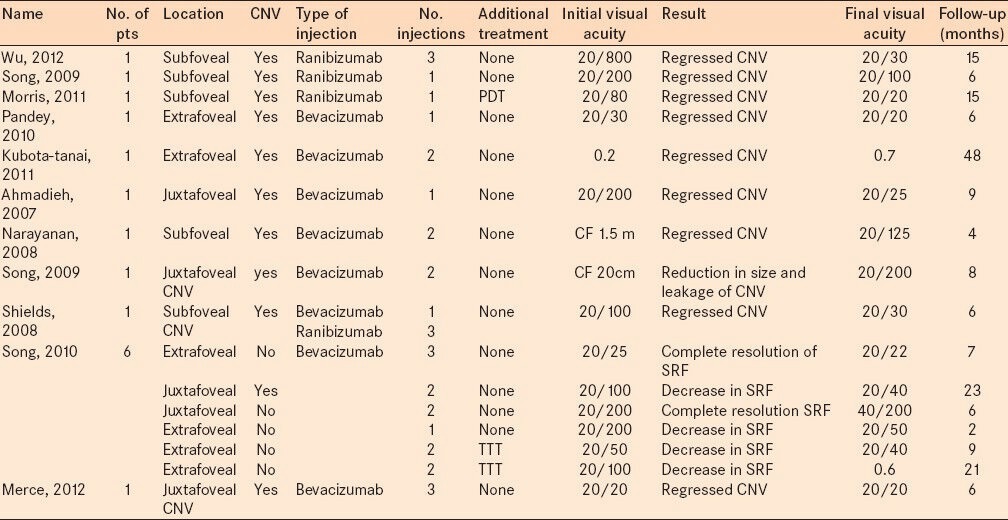

Since the approval of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) intravitreal injections in age-related macular degeneration, several reports have emerged about the use of bevacizumab28,32,55,56,57,58,59,60 and ranibizumab28,58,61,62 in the treatment of CNV associated with choroidal osteoma [Table 2]. Ranibizumab or bevacizumab intravitreal injections resulted in regression of CNV, resolution of associated subretinal fluid and improvement in visual acuity. Some patients required more than one injection, with a total average of 1.8 injections [Table 2]. Others required the adjunct use of additional modalities such as PDT or TTT.32,62 These results were maintained over an average of 12 months of follow up, some up to 4 years.59 The favorable visual outcome following bevacizumab or ranibizumab injections is credited to the decrease in VEGF which, even at physiologic levels, might reduce the permeability of choroidal vessels.32 It has also been estimated that VEGF is up regulated secondary to chronic inflammation and mild ischemia caused by the choroidal tumor.59 Also the good results may be attributed to better drug availability through improved penetration of a thinned and degenerated RPE55 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Literature review of case reports analyzing the use of intravitreal vascular endothelium growth factor (VEGF) antagonists in choroidal osteoma

Serous retinal detachment not associated with CNV

As previously mentioned, a second large category of serous retinal detachment overlying choroidal osteomas is not associated with CNV.4 Browning suggested treating these eyes using light focal laser.40 TTT was also successfully used in treating serous retinal detachment not associated with CNV with good results.63 Song injected intravitreal bevacizumab in 5 eyes with serous retinal detachment not associated with CNV.32 All 5 eyes had a significant decrease in subretinal fluid, as well as improved visual acuity in all but one case.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gass JD, Guerry RK, Jack RL, Harris G. Choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:428–35. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050204002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams AT, Font RL, Van Dyk HJ, Riekhof FT. Osseous choristoma of the choroid simulating a choroidal melanoma. Association with a positive 32 P test. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:1874–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060378017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields CL, Sun H, Demirci H, Shields JA. Factors predictive of tumor growth, tumor decalcification, choroidal neovascularization, and visual outcome in 74 eyes with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1658–66. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aylward GW, Chang TS, Pautler SE, Gass JD. A long-term follow-up of choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1337–41. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.10.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields CL, Shields JA, Augsburger JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;33:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gass JD. New observations concerning choroidal osteomas. Int Ophthamol. 1979;1:71–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00154194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noble KG. Bilateral choroidal osteoma in three siblings. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:656–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunha SL. Osseous choristoma of the choroid: A familial disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1052–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030854032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aoki J. Familial bilateral occurrence of choroidal osteoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1985;39:1319–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz RS, Gass JD. Multiple choroidal osteomas developing in association with recurrent orbital inflammatory pseudotumor. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1724–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020726012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trimble SN, Schatz H. Choroidal osteoma after intraocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:759–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLeod BK. Choroidal osteoma presenting in pregnancy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:612–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.8.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figueira EC, Conway RM, Francis IC. Choroidal osteoma in association with Stargardt's dystrophy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;9:978–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fine HF, Ferrara DC, Ho IV, Takahashi B, Yannuzzi LA. Bilateral choroidal osteomas with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retinal Cases Brief Rep. 2008;2:15–7. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e318159e7e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spies AK, Teitelbaum BA, Aide FK. An atypical case of choroidal osteomas. Optometry. 2001;72:322–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kline LB, Skalka HW, Davidson JD, Wilmes FJ. Bilateral choroidal osteomas associated with fatal systemic illness. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:192–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90414-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joffe L, Shields JA, Fitzgerald JR. Osseous choristoma of the choroid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:1809–12. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060321004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Lee L, Gass JD. Choroidal osteoma: Evidence of progression and decalcification over 20 years. Clin Exp Optom. 2006;89:90–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2006.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose SJ, Burke JF, Brockhurst RJ. Argon laser photoablation of a choroidal osteoma. Retina. 1991;11:224–8. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199111020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Augsburger JJ, Shields JA, Rife CJ. Bilateral choroidal osteoma after nine years. Can J Ophthalmol. 1979;14:281–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shields JA, Shields CL, de Potter P, Belmont JB. Progressive enlargement of a choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:819–20. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100060145049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizota A, Tanabe R, Adachi-Usami E. Rapid enlargement of choroidal osteoma in a 3-year-old girl. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1128–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.8.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trimble SN, Schatz H. Decalcification of a choroidal osteoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:61–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trimble SN, Schatz H, Schneider GB. Spontaneous decalcification of a choroidal osteoma. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:631–4. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shields CL, Perez B, Materin MA, Mehta S, Shields JA. Optical coherence tomography of choroidal osteoma in 22 cases: Evidence for photoreceptor atrophy over the decalcified portion of the tumor. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:e53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buettner H. Spontaneous involution of a choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1517–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070130019009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurelik G, Lonneville Y, Safak N, Ozdek SC, Hasanreisoglu B. A case of choroidal osteoma with subsequent laser induced decalcification. Int Ophthalmol. 2001;24:41–3. doi: 10.1023/a:1014470730194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shields CL, Materin MA, Mehta S, Foxman BT, Shields JA. Regression of extrafoveal choroidal osteoma following photodynamic therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:135–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navajas EV, Costa RA, Calucci D, Hammoudi DS, Simpson ER, Altomare F. Multimodal fundus imaging in choroidal osteoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:890–5.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster BS, Fernandez-Suntay JP, Dryja TP, Jakobiec FA, D'Amico DJ. Clinicopathologic reports, case reports, and small case series: Surgical removal and histopathologic findings of a subfoveal neovascular membrane associated with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:273–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kadrmas EF, Weiter JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1997;37:171–82. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199703740-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song JH, Bae JH, Rho MI, Lee SC. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of subretinal fluid associated with choroidal osteoma. Retina. 2010;30:945–51. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181c720ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ide T, Ohguro N, Hayashi A, Yamamoto S, Nakagawa Y, Nagae Y, et al. Optical coherence tomography patterns of choroidal osteoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:131–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DePotter P, Shields JA, Shields CL, Rao VM. Magnetic resonance imaging in choroidal osteoma. Retina. 1991;11:221–3. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199111020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sisk RA, Riemann CD, Petersen MR, Foster RE, Miller DM, Murray TG, et al. Fundus autofluorescence findings of choroidal osteoma. Retina. 2013;33:97–104. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31825c1cde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shields CL, Shields JA, De Potter P. Patterns of indocyanine green videoangiography of choroidal tumours. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:237–45. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freton A, Finger PT. Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography analysis of choroidal osteoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:224–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2011.202408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sayanagi K, Pelayes DE, Kaiser PK, Singh AD. 3D spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in choroidal tumors. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:271–5. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2010.5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukasawa A, Iijima H. Optical coherence tomography of choroidal osteoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:419–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Browning DJ. Choroidal osteoma: Observations from a community setting. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1327–34. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Honavar SG, Shields CL, Demirci H, Shields JA. Sclerochoroidal calcification: clinical manifestations and systemic associations. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:833–40. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffman ME, Sorr EM. Photocoagulation of subretinal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:998–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060070142045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grand MG, Burgess DB, Singerman LJ, Ramsey J. Choroidal osteoma. Treatment of associated subretinal neovascular membranes. Retina. 1984;4:84–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burke JF, Jr, Brockhurst RJ. Argon laser phtocoagulation of subretinal neovascular membrane associated with osteoma of the choroid. Retina. 1983;3:304–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198300340-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Avila MP, El-Markabi H, Azzolini C, Jalkh AE, Burns D, Weiter JJ. Bilateral choroidal osteoma with subretinal neovascularization. Ann Ophthalmol. 1984;16:381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrison D, Magargal LE, Ehrlich DR, Goldberg RE, Robb-Doyle E. Review of choroidal osteoma: successful krypton red laser photocoagulation of an associated subretinal neovascular membrane involving the fovea. Ophthalmic Surg. 1987;18:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopez PF, Green WR. Peripapillary subretinal neovascularization, a review. Retina. 1992;12:147–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander TA, Hunyor AB. Choroidal osteomas. Aust J Ophthalmol. 1984;12:373–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1984.tb01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eting E, Savir H. An atypical fulminant course of choroidal osteoma in two siblings. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:52–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75753-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma S, Sribhargava N, Shanmugam MP. Choroidal neovascular membrane associated with choroidal osteoma (CO) treated with trans-pupillary thermo therapy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2004;52:329–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shukla D, Tanawade RG, Ramasamy K. Transpupillary thermotherapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascular membrane in choroidal osteoma. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:845–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Battaglia Parodi M, Da Pozzo S, Toto L, Saviano S, Ravalico G. Photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma. Retina. 2001;21:660–1. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200112000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blaise P, Duchateau E, Comhaire Y, Rakic JM. Improvement of visual acuity after photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization in choroidal osteoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83:515–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh AD, Talbot JF, Rundle PA, Rennie IG. Choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroidal osteoma: Successful treatment with photodynamic therapy. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:482–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmadieh H, Vafi N. Dramatic response of choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma to the intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:1731–3. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Narayanan R, Shah VA. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to choroidal osteoma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18:466–8. doi: 10.1177/112067210801800327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pandey N, Guruprasad A. Choroidal osteoma with choroidal neovascular membrane: Successful treatment with intravitreal bevacizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:1081–4. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S13730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song MH, Roh YJ. Intravitreal ranibizumab in a patient with choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroidal osteoma. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1745–6. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kubota-Taniai M, Oshitari T, Handa M, Baba T, Yotsukura J, Yamamoto S. Long-term success of intravitreal bevacizumab for choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1051–5. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mercé E, Korobelnik JF, Delyfer MN, Rougier MB. Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab for CNV secondary to choroidal osteoma and follow-up by spectral-domain OCT. Article in French. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2012;35:508–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu ZH, Wong MY, Lai TY. Long-term follow-up of intravitreal ranibizumab for the treatment of choroidal neovascularization due to choroidal osteoma. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2012;3:200–4. doi: 10.1159/000339624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morris RJ, Prabhu VV, Shah PK, Narendran V. Combination therapy of low-fluence photodynamic therapy and intravitreal ranibizumab for choroidal neovascular membrane in choroidal osteoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:394–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.83622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yahia SB, Zaouali S, Attia S. Serous retinal detachment secondary to choroidal osteoma successfully treated with transpupillary thermotherapy. Retinal Cases Brief Rep. 2008;2:126–7. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31802f6ef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]