Abstract

To describe three presentations of spitting cobra venom induced ophthalmia in urban Singapore. Case notes and photographs of three patients with venom ophthalmia who presented to our clinic between 2007 and 2012 were reviewed. Two patients encountered the spitting cobra while working at a job site while the third patient had caught the snake and caged it. The venom entered the eyes in all 3 cases. Immediate irrigation with tap water was carried out before presenting to the Accident and Emergency department. All patients were treated medically with topical antibiotic prophylaxis and copious lubricants. The use of anti-venom was not required in any case. All eyes recovered with no long-term sequelae. If irrigation is initiated early, eyes can recover with no significant complications or sequelae.

Keywords: Naja Sumatrana, Ocular Envenomation, Spitting Cobra, Venom Ophthalmia

INTRODUCTION

A family of snakes known as spitting Elapidae uses venom defensively by spitting it into the eyes of potential predators or threats while attempting to slither to safety. The majority of published cases of direct inoculation of cobra venom to the eye have been reported in rural Africa, caused by the species Naja nigricolis.1 Some cases have been reported in Asia that generally occurred in rural areas or from snakes in captivity.2 Victims experiencing a host of different clinical presentations have been documented. We report three separate cases of venom ophthalmia that were encountered in an urban setting.

All three patients presented to the Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences Department, Alexandra Hospital, Singapore, between 2007 and 2012. All patients had symptoms of severe burning eye pain, photophobia and foreign body sensation.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 28-year-old Thai male who was clearing debris at a construction site when he encountered a spitting cobra. The reptile spat venom into his right eye before trying to escape. A colleague who was also at the site managed to kill the cobra [Figure 1]. The species of the snake was later identified and confirmed as Naja sumatrana. His co-workers managed to irrigate his eye for several minutes with tap water and he was re-irrigated in the Accident and Emergency (A and E) Department with half a litre of normal saline (0.9% NaCl). On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/50 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. He had multiple corneal punctate epithelial erosions, conjunctival injection and chemosis, especially around a pre-existing pterygium, as well as mild corneal stromal edema [Figure 2]. There was no anterior chamber reaction, intraocular pressure was normal and dilated fundus examination was unremarkable. The fellow eye was normal. The patient was treated with chloramphenicol eye drops four times a day and preservative-free lubricants hourly. One week later, his right BCVA had returned to 20/20 without any further sequelae.

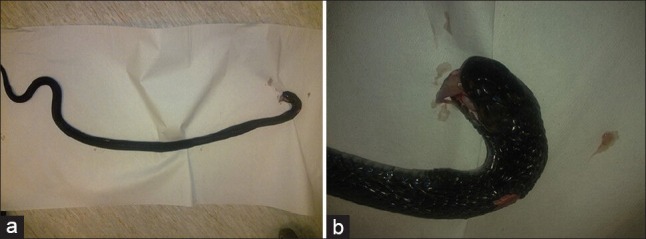

Figure 1.

(a) Picture of the Naja Sumatrana which attacked our first patient (b) Close-up picture of the snake

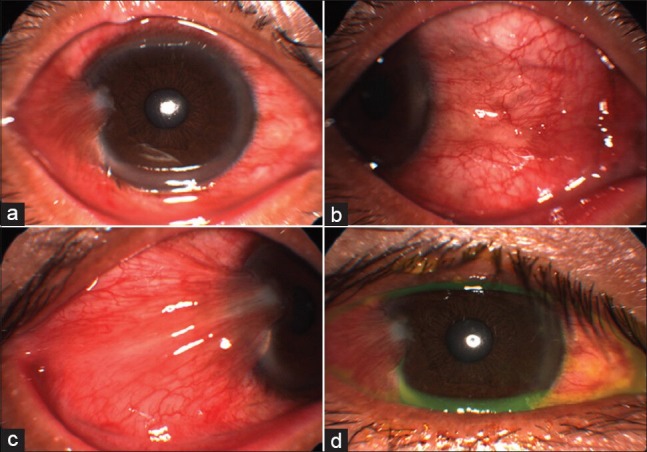

Figure 2.

The first patient's right eye at presentation. (a and b) Injected eye at presentation (c) Injection and chemosis of pterygium (d) Fluorescein staining showing punctuate epithelial erosions

Case 2

A 23-year-old Chinese male who was gathering fallen tree branches when he uncovered a spitting cobra under the branches that spat into his left eye. The snake, which managed to escape, fitted the description of the Naja sumatrana. The worker's supervisor who was on site assisted him with irrigation of the affected eye for 10 minutes with tap water before he was brought for consultation at the A and E department. On examination, BCVA was 20/20 in both eyes. The left eye showed corneal punctate epithelial erosions and conjunctival injection but no iridocyclitis [Figure 3a and b], while the fellow eye was normal. Intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. Dilated fundus examination was unremarkable bilaterally. The patient was treated with chloramphenicol eye drops four times a day and preservative-free lubricants hourly. A week after the incident, his eye had recovered completely [Figure 3c and d].

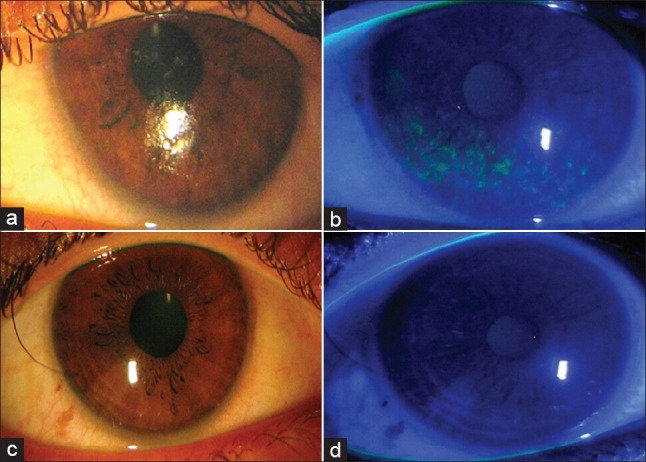

Figure 3.

Images of the second patient's left eye (a) Color photo of left eye at presentation (b) Eye at presentation with Fluorescein staining showing epithelial erosions (c) Left eye after 1 week (d) Left eye after 1 week with Fluorescein staining

Case 3

A 41-year-old Chinese male had caught a snake and caged it. The snake, which also fitted the description of the Naja sumatrana, spat into his left eye while in captivity. He promptly irrigated his eye for 10 minutes with tap water before presenting to the A and E department where further irrigation was performed with half a litre of normal saline solution. Examination revealed conjunctival injection and minimal punctuate epithelial erosions in the left eye without other clinical findings. The patient was treated with chloramphenicol eye drops four times a day and preservative-free lubricants hourly. He returned only a month later (failing to show for an earlier follow up visit), and the eye had completely recovered.

DISCUSSION

The most common species of spitting cobra found in the Malaysian-Singapore peninsula is the Naja sumatrana.3 Reports including those from Africa show that the ocular effects of direct inoculation of venom from Naja nigricolis and other species is highly variable even to the extent of vision loss in some cases and mostly occurring in rural settings. To our knowledge this is the first report of spitting cobra venom ophthalmia in Singapore. Notably, these incidents occurred in an urban setting with good clinical outcome and no major sequelae.

The general principle of prompt and copious irrigation of the eyes whenever there is chemical contact cannot be overemphasized. We believe that snake venom which is a mixture of chemicals, should be initially washed out by irrigation. We used normal saline (0.9% NaCl) as this is the standard irrigating solution at our institution. Nevertheless, any crystalloid should suffice as the principle is to remove as much of the inciting agent as possible. With the patient lying supine or reclined, an infusion set was used to irrigate the normal saline directly into the eyes after applying topical anesthetic drops and a kidney tray to collect the contaminated saline. Others have reported using a Morgan therapeutic lens, which is shown to be well tolerated, to aid the irrigation.4 Mydriatics such as atropine and homatropine and anti-inflammatory have been advocated in patients with anterior chamber inflammation, to reduce the risk of formation of posterior synechiae, as well as to improve patient comfort. Topical antibiotics (such as chloramphenicol) can be used in patients with extensive corneal erosions to prevent secondary infection. Other less conventional treatment modalities include the use of topical anti-venom and heparin.5,6 The use of topical heparin has also been explored but only in experimental animal studies, with significant improvement in overall outcomes in rabbit eyes exposed to Naja sumatrana venom, with or without concomitant use of topical tetracycline ointment.6 The Naja sumatrana venom is composed of neurotoxins, cardiotoxins and necrotoxins with high acetylcholinesterase, hyaluronidase and phospholipase activities.7 Therefore, local necrosis and systemic absorption of the venom would be a concern with direct inoculation of the venom into the eye with prolonged contact. Extensive necrosis of the eye requiring evisceration, as well as systemic envenomation for which systemic anti-venom was administered has been previously described for other snake species.8 However, there have been no reports of systemic absorption of spitting cobra venom after having sustained a spitting injury. Furthermore, species identification was not needed in these cases because systemic anti-venom was not required.

Clinically, since our patients' conditions were less severe, we chose to manage them analogous to a chemical splash injury with copious irrigation, lubricants and topical antibiotics with good overall effect. The relatively intact cornea and ocular surface in our cases, complemented by prompt irrigation could have acted as a successful protective barrier for further intraocular and systemic spread of the venom.

Despite rapid urbanization, spitting cobra venom ophthalmia - a condition which is more commonly encountered in the wild and rural environment - can be seen in urbanized areas. As far as possible, these snakes should not be handled, caught or held captive as presented in our last case. Captive snakes can be aggressive and still cause spitting injuries. We strongly discouraged captivity of these and a public education campaign or warning should be issued. Ophthalmologists such are cognizant of such occurrences. Regardless of the venom or toxin that the eye is exposed to, it is well-documented that prompt and copious irrigation is the key to preventing any chronic visual morbidity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaylock R. Epidemiology of snakebite in Eshowe, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Toxicon. 2004;43:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu ER, Weinstein SA, White J, Warrell DA. Venom ophthalmia caused by venoms of spitting elapid and other snakes: Report of ten cases with review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathophysiology and management. Toxicon. 2010;56:259–72. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wüster W. Taxonomic changes and toxinology: Systematic revisions of the Asiatic cobras (Naja naja species complex) Toxicon. 1996;34:399–406. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones JB, Schoenleber DB, Gillen JP. The tolerability of lactated Ringer's solution with BSS plus for ocular irrigation with and without the Morgan therapeutic lens. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:1150–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson R. Ophthalmic exposure to crotalid venom. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:37–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cham G, Pan JC, Lim F, Earnest A, Gopala Krishna kone P. Effects of topical heparin, anti-venom, tetracycline and dexamethasone treatment in corneal injury resulting from the venom of the black spitting cobra (Naja sumatrana), in a rabbit model. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44:287–92. doi: 10.1080/15563650600584451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yap MK, Tan NH, Fung SY. Biochemical and toxicological characterization of Naja sumatrana (Equatorial spitting cobra) venom. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2011;17:451–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CC, Yang CM, Hu FR, Lee YC. Penetrating ocular injury caused by venomous snakebite. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:544–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]