Abstract

In photovoltaic devices, light harvesting (LH) and carrier collection have opposite relations with the thickness of the photoactive layer, which imposes a fundamental compromise for the power conversion efficiency (PCE). Unbalanced LH at different wavelengths further reduces the achievable PCE. Here, we report a novel approach to broadband balanced LH and panchromatic solar energy conversion using multiple-core-shell structured oxide-metal-oxide plasmonic nanoparticles. These nanoparticles feature tunable localized surface plasmon resonance frequencies and the required thermal stability during device fabrication. By simply blending the plasmonic nanoparticles with available photoactive materials, the broadband LH of practical photovoltaic devices can be significantly enhanced. We demonstrate a panchromatic dye-sensitized solar cell with an increased PCE from 8.3% to 10.8%, mainly through plasmon-enhanced photo-absorption in the otherwise less harvested region of solar spectrum. This general and simple strategy also highlights easy fabrication, and may benefit solar cells using other photo-absorbers or other types of solar-harvesting devices.

Keywords: Tunable localized surface plasmon, light harvesting enhancement, panchromatic dye-sensitized solar cells, multiple-core-shell nanoparticles

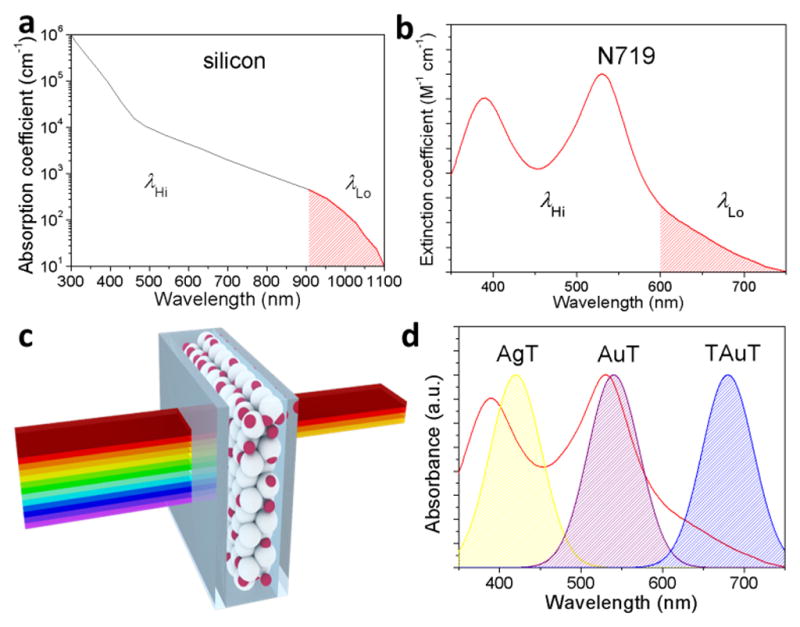

Developing efficient and inexpensive solar cells is of paramount importance for preserving non-renewable energy and lowering carbon dioxide emissions. The power conversion efficiency (PCE) of the solar cells is generally governed by the tradeoff between light harvesting (LH) and carrier collection. To break this compromise, strategies of improving either LH or carrier collection while maintaining the other have been successful1, 2. However, most photo-absorbing materials possess unbalanced LH in high- and low-absorption wavelength regions (λHi and λLo, figure 1a, b), which results in another tradeoff. At λLo, long absorption lengths are required, which reduce carrier collection; at λHi, solar energy is fully-absorbed by thin photoactive layers, which inefficiently exploit energy at λLo (usually the red to near-infrared (NIR) region, figure 1c). Consequently, the ability to achieve broadband balanced LH is desirable for high-efficiency solar cells.

Figure 1. Spectral response of the LH of a solar cell and tunable LSP-enhanced broadband LH.

a, b, the absorption coefficient of bulk silicon (a) and extinction coefficient of N719 (b); the shaded areas are low LH regions, which require thicker photoactive layers to achieve efficient LH. c, a schematic of the spectral response of a solar cell. The solar energy is less utilized at λLo (usually red-NIR). d, illustrations of enhancing EM intensity by AgT (yellow), AuT (purple), and TAuT (blue) plasmonic NPs. λLSPR of AgT and AuT overlaps with λHi of N719, maximizing the effect of LSP-enhanced LH. λLSPR of TAuT matches λLo of N719, balancing LH at different wavelengths.

Achieving such broadband balanced LH would lead to panchromatic solar energy conversion, an ideal strategy for maximizing overall LH. As a promising solution-processed photovoltaic technology, dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) have demonstrated PCE exceeding 12%3–8; to further improve the PCE, several approaches toward panchromatic DSSCs9 have been attempted, including the development of panchromatic dyes10, co-adsorbing dyes11, and energy transfer systems12. However, these methods usually require extensive synthesis and optimization for various parameters (e.g., spectral overlapping and spatial arrangement) and are limited to small ranges of materials. Therefore, a general and simple approach for broadband balanced LH and panchromatic DSSCs is required.

Localized surface plasmons (LSPs) are the elementary excitation states in noble metal nanoparticles (NPs), and can improve LH of photo-absorbers2, 13–18. Here, we introduce a general and simple strategy for broadband LH enhancement and panchromatic DSSCs by matching LSP resonance (LSPR) wavelength (λLSPR) of plasmonic NPs with λLo of existing photo-absorbers. Demonstrated by both simulations and experiments, matching λLSPR with λHi or λLo affects LH differently (figure 1d). Although matching λLSPR with λHi readily improves LH and PCE for optically-thin photo-absorbing layers, matching λLSPR with λLo maximally increases LH and PCE for practical photovoltaic devices with optically-thick layers, through enhancing photo-absorption in the weakly-absorbing region. The multiple-core-shell oxide-metal-oxide plasmonic NPs developed and utilized here are advantageous over other geometries, by featuring: adjustable λLSPR of 600–1,000 nm, substantially enhanced near-field electromagnetic (EM) intensity, and preservable plasmonic properties during device fabrication. By matching λLSPR with λLo of a common dye (N719), a panchromatic DSSC with broadband balanced LH and a PCE of 10.8% is achieved (30% increase comparing to DSSCs without plasmonic NPs).

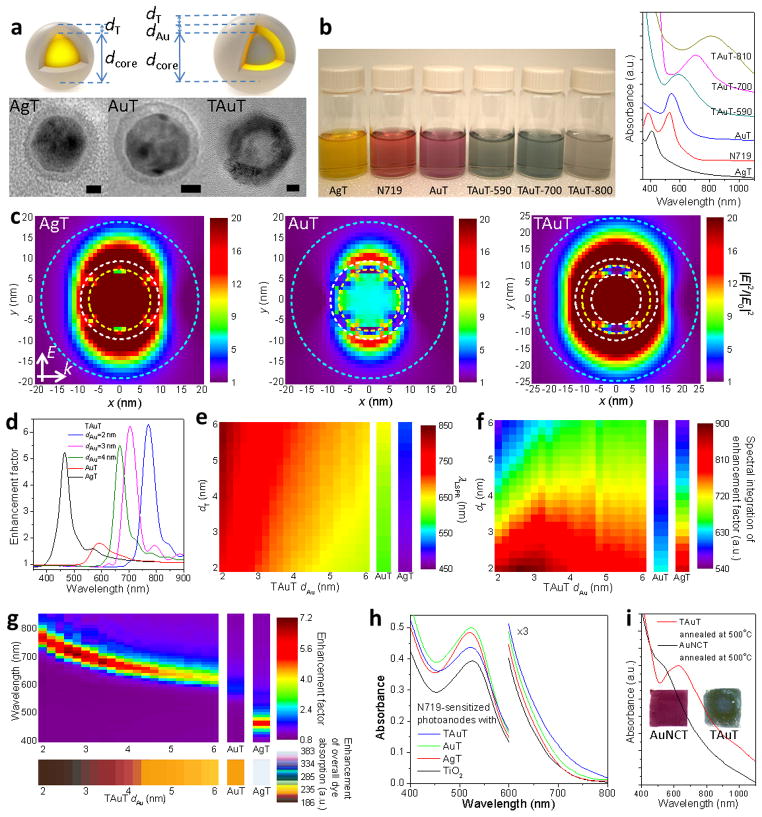

Synthesis and optical characterization are performed for the core-shell (dcore~15 nm, dT~2 nm) Ag@TiO2 (AgT) and Au@TiO2 (AuT) and multiple-core-shell (dcore~15 nm, dAu~0–4 nm, and dT~2 nm) TiO2-Au-TiO2 (TAuT) NPs (figure 2a, S3–S6). dcore, dAu, and dT represent core diameter, gold-shell thickness, and TiO2-shell thickness, respectively. When synthesizing the gold-shell of TAuT NPs, Au seeds gradually cover the core and coalesce to form a continuous layer, which is stable at 500°C (annealing condition for DSSCs). The outer TiO2-shells impede the metals from promoting recombination in the DSSCs2, 14. The λLSPR of AgT and AuT NPs are 420 and 550 nm respectively, and the λLSPR of TAuT NPs is continuously tunable from 1,000 to 600 nm by increasing dAu to 4 nm (figure 2b). Tunable λLSPR across visible-NIR is thus achieved.

Figure 2. Synthesis, optical characterization, and FDTD simulation of AgT, AuT, and TAuT plasmonic NPs.

a, illustrations and transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of AgT, AuT, and TAuT NPs. The scale bars are 5 nm. b, photograph picture and absorption spectra of AgT, N719, AuT, TAuT-590 (λLSPR=590 nm), TAuT-700, and TAuT-810 in ethanol solutions. c, simulated EM intensity enhancement (|E|2/|E0|2) in near field at λLSPR for AgT, AuT, and TAuT NPs. The inner circles (white and yellow) represent different layers of NPs, and the outermost circles (cyan) represent the volume of integration. dcore=15 nm (used for all simulations unless specified), dAu=3 nm, and dT=2 nm. d, enhancement factor as a function of wavelength for AgT, AuT, and TAuT NPs with different dAu (dT=2 nm). e, f, simulated λLSPR (e) and spectrum-integrated enhancement factor over 300–900 nm (f) for AgT, AuT, and TAuT NPs as a function of dAu (of TAuT) and dT (of AgT, AuT, and TAuT). g, enhancement factor at different wavelengths (top) and enhancement of overall dye absorption (bottom) for AgT, AuT, and TAuT with different dAu (dT=2 nm). h, absorption of N719 in sensitized 3-ϕm-thick TiO2 films improved by AgT (1.0 wt%), AuT (1.8 wt%), and TAuT (3.2 wt%) NPs. i, absorption spectra and photograph images of thin films of Au nanocage@TiO2 (AuNCT, left) and TAuT-700 (right) on glass substrates after 500°C annealing; TAuT NPs maintain optical properties, whereas λLSPR of AuNCT blue-shifts toward λLSPR of AuT NPs.

The interaction of the NPs with light was investigated using the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method. All plasmonic NPs strongly amplify the near-field EM intensity (figure 2c). Therefore, surrounding dye-molecules would experience a significantly increased light intensity near the LSPR frequency16, 19 and a higher photon flux (ϕph), which increases electron-hole pair generation. The enhancement factors (derived by integrating over near-field space, figure S7) of plasmonic NPs as functions of wavelength (figure 2d) show similar results of λLSPR to those obtained from absorption spectra. The characteristic absorption peak of the TAuT NPs originates from the LSPs arising in the gold-shell structure20–23. By tuning dAu and dT of TAuT NPs in 2–6 nm, λLSPR of 600–800 nm is achieved; as expected, thinner gold- and thicker TiO2-shells result in longer λLSPR (figure 2e, S8). Furthermore, an optimum dAu~3 nm maximizes the spectrum-integrated enhancement factor and thicker TiO2-shells tend to weaken the enhancement (figure 2f, the enhancement factor at λLSPR is shown in figure S9). The λLSPR and enhancement factors are also obtained for AgT and AuT NPs, which extend the LSP-enhanced spectral range to vis-NIR. These results represent the intrinsic near-field enhancement of plasmonic NPs and do not take the spectral response of dye-molecules into account.

The impact on the photo-absorption of surrounding dye-molecules is investigated by comparing the enhancement factors at different wavelengths (figure 2g, S10). At λLo=600–800 nm (for N719), the greatest enhancement occurs by using TAuT NPs (e.g., dAu~3 nm and dT~2 nm for 700 nm), where λLSPR matches λLo; at λHi=400–600 nm, the maximum enhancement occurs by using AuT and AgT NPs, where λLSPR matches λHi. The overall dye absorption is also maximally improved by AgT and AuT NPs (bottom part of figure 2g). These results and the simulated LSP-enhanced dye absorption (λLSPR=400–700 nm, figure S11) suggest that, on the level of individual plasmonic NP, matching λLSPR with λHi enhances overall LH of dye-molecules more efficiently, whereas matching λLSPR with λLo balances LH in a broad spectral range.

Moreover, the LSP-enhanced LH of N719-sensitized mesoporous TiO2 films (figure 2h) agrees with the simulation results. AgT and AuT NPs improve LH mostly at λHi, whereas TAuT NPs (TAuT-700 NPs with λLSPR=700 nm are used for all thin film LH and device performance characterizations) increase LH at λLo, resulting in balanced spectra. The similar enhancements of simulated EM intensity and LH of thin films around λLSPR (supplementary discussion) confirm that the LH improvement stems from the interaction between dye-molecular dipoles and the LSP-enhanced near field and scattering cross-section of the NPs.

The multiple-core-shell oxide-metal-oxide plasmonic NPs are advantageous over other geometries (e.g. nanorods, nanodisks, and hollow nanoshells) which also possess tunable λLSPR in vis-NIR20, 24. Under thermal treatment, the TAuT NPs maintain geometric and plasmonic properties with the rationally-designed templated metal-shell structure, while other geometries melt to spheres or spheroids and the characteristic λLSPR blue-shifts (figure 2i, S12, S13), severely reducing the ability to enhance LH at λLo. In addition, little change in synthesis is required to tune λLSPR of TAuT NPs due to their high sensitivity to geometry (supplementary discussion). Moreover, metal-shell structures (e.g. TAuT, hollow gold-shell (figure S15, S16), and TAgT (figure S17, S18)) possess larger EM field enhancement than spherical solid metal structure (e.g. AuT and AgT). Therefore, the multiple-core-shell plasmonic NPs can benefit many LSP-enhanced applications which require tunable spectral response and high temperature fabrications. In addition, unlike the method using the inter-particle coupling25 to tune λLSPR, the current approach does not require sophisticated chemistry to control particle aggregation and the enhanced EM field uniformly surrounds the plasmonic NPs.

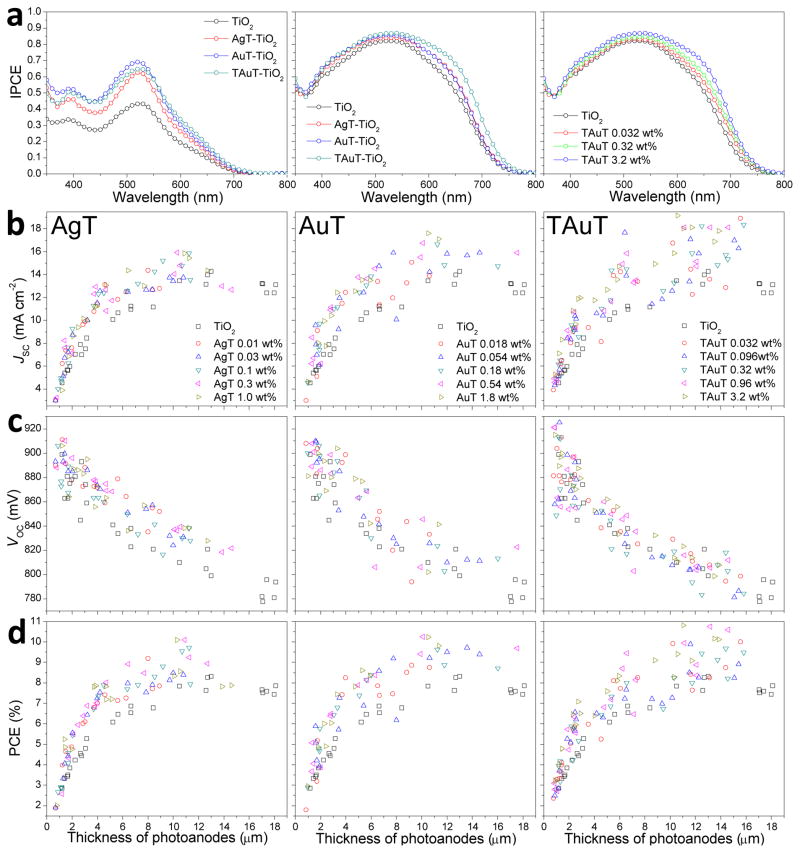

To study the LH of tunable LSP-enhanced DSSCs, different plasmonic NPs-incorporated TiO2 photoanodes (thickness of 1–20 μm and plasmonic NPs-TiO2 ratio of 0.01–3.2 wt%) are assembled into DSSCs1, 2. In 1.5-μm-thick optically-thin photoanodes, AgT, AuT, and TAuT NPs increase the incident photon-to-current conversion efficiency (IPCE) at λmax (maximum absorption wavelength~530 nm) by 45%, 60%, and 50%, respectively (figure 3a-left). Enhancement is maximized when λLSPR is closest to λmax. Similarly, at 700 nm, TAuT NPs increase IPCE the most by 80%, whereas AgT and AuT NPs enhance IPCE only by 21% and 22% due to large mismatch between λLSPR and λLo. By correlating the absorbance, LH efficiency (LHE), and IPCE (supplementary discussion), we find that the experimental results of absorbance and IPCE enhancement are similar, which indicate that the IPCE improvement mainly arises from LSP-enhanced LH.

Figure 3. Tunable LSP-enhanced LH and photovoltaic performance of DSSCs.

a, IPCE spectra of DSSCs with AgT, AuT, and TAuT NPs-incorporated photoanodes of 1.5 ϕm thickness (left), of optimized thickness for maximum PCE (middle), and as a function of concentration of TAuT NPs in optimized TAuT-DSSCs (right). b, c, d, JSC (b), VOC (c), and PCE (d) of LSP-enhanced DSSCs with AgT (left), AuT (middle), and TAuT (right) NPs-incorporated photoanodes, as a function of the concentration of plasmonic NPs (0–3.2 wt%) and thickness of photoanodes (1–20 ϕm). The particle densities for all plasmonic NPs are the same and in the range of 8.4×1012–8.4×1014 cm−3, and the difference in weight percent is due to the different geometries of NPs (supplementary discussion).

While IPCE (specifically LHE) of thin photoanodes is readily increased by LSPs, optically-thick photoanodes (10~15 μm) for practical devices are required to ensure balance between LH and carrier collection for maximized PCE26, where the LHE at λHi and internal quantum efficiency are close to unity. At λmax, less than 5% enhancement of IPCE for all plasmonic NPs is observed (figure 3a-middle, supplementary discussion). In contrast, at λLo, the TAuT NPs increase IPCE by up to 100%, whereas AgT and AuT NPs increase IPCE slightly. Additionally, the IPCE increases monotonically with the concentration of TAuT NPs (figure 3a-right).

Therefore, both experiments and simulations have demonstrated that matching λLSPR with λHi or λLo impacts the spectral response of LH differently. Matching λLSPR with λHi enhances LH in already strongly-absorbing region, which benefits optically-thin photoanodes. In contrast, matching λLSPR with λLo improves the weakly-absorbed part of solar spectrum, which is of great importance for broadband balanced LH in practical panchromatic solar cells.

The PCEs of tunable LSP-enhanced DSSCs are measured (figure S19, table S1) (PCE=JSCVOCFF/Pin, JSC, VOC, FF, and Pin represent short-circuit current density, open-circuit voltage, fill factor, and incident power density, separately). JSC (=q ∫ IPCE(λ) ϕph(λ)dλ) is improved with increasing concentrations of plasmonic NPs (within the concentration range studied); the largest JSC is achieved by incorporating the highest concentration of TAuT NPs (figure 3b). Besides the improved LH, thinner photoanodes for optimized PCEs (the optimized thicknesses for TiO2, AgT, AuT, and TAuT DSSCs are 13.2, 10.9, 10.1, and 11.0 μm) are also responsible for the improved IPCE and JSC, by improving the carrier collection (electron diffusion lengths are not changed significantly, figure S22).

Additionally, VOC is increased by introducing plasmonic NPs (figure 3c). Generally, VOC is limited by the material properties of electronic structure (e.g., the quasi-Fermi level of TiO2 and redox potential of electrolyte); enhancing VOC usually requires exploiting new materials3. Two reasons could be responsible for the LSP-induced VOC enhancement: thinner optimized photoanodes reduce the voltage loss from charge recombination; and the quasi-Fermi level is lifted due to the equilibrium between quasi-Fermi level of TiO2 and LSP energy level of plasmonic NPs15, 27. Our result is also in agreement with a recent study on plasmoelectronics28. In addition, we observe that TAuT NPs increase VOC less significantly than AgT and AuT NPs, which is likely due to lower LSP energy level (supplementary discussion). The different VOC enhancements could assist in the elucidation of the origin of LSP-enhanced VOC, and the ability of rationally increasing VOC could further improve PCE. In addition, although we suggest that the VOC increase is due to quasi-Fermi level equilibrium, we do not yet have direct evidence of charge transfer from metal to TiO2. Regarding this subject, we plan to perform further investigation.

Since LSPs have a larger effect on enhancing LH than changing VOC and FF (no significant impact on FF is observed, figure S23), the PCEs are improved (figure 3d) with increasing concentrations of NPs (0–3.2 wt%, higher concentrations could reduce performance, supplementary discussion). Thus, maximum PCEs of 10.1%, 10.3%, and 10.8% are achieved for AgT, AuT, and TAuT NPs-incorporated DSSCs respectively, comparing to 8.3% without plasmonic NPs.

The optimized device performance helps distinguish the improvement from different plasmonic NPs. AgT and AuT NPs used here and similar materials in previous studies on LSP-enhanced DSSCs2, 14–16 improve IPCE and PCE, mainly through improved LH at λHi. Although the previous approach is responsible for achieving ultrathin solar cells29, it could not break the compromise imposed by unbalanced LH at λHi and λLo. In contrast, our general and simple strategy of matching λLSPR with λLo balances and optimizes broadband LH, achieves panchromatic DSSCs with the existing dye, and further enhances LH, JSC, and PCE. In fact, the distribution of core sizes and shell thicknesses result in the broad absorption spectrum of TAuT NPs with λLSPR~λLo (figure 2b), which benefits panchromatic LH and carrier collection simultaneously. Our approach toward panchromatic DSSCs can apply to other photo-absorbers and other types of solar cells. For instance, a PCE of 12% was achieved by using a porphyrin dye in the DSSC3. We believe that the same strategy can be used to improve the overall LH by matching the λLSPR with the λLo and a similar degree of improvement would be observed. Furthermore, since LH is the initial stage of a series of physical, chemical, or biochemical processes in many solar energy conversion devices, our strategy of matching λLSPR with λLo may benefit many other devices30 including artificial photosynthesis18, solar heating, solar thermal electricity, and solar fuels31.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Eni, S.p.A (Italy) through the MIT Energy Initiative Program. N.X.F. acknowledges support by NSF (ECCS Award No. 1028568) and by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR MURI Award No. FA9550-12-1-0488). M.T.K acknowledges support from the MIT Energy Initiative Eni-MIT Energy Fellowship.

Footnotes

Author contributions

X.D., J.Q., P.T.H., and A.M.B. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. X.D. and J.Q. performed the synthesis. X.D., J.Q., and D.S.Y. performed the TEM imaging. M.T.K. and N.X.F. performed the simulation. X.D., M.T.K., and N.X.F. analyzed the simulation results. X.D., J.Q., and P.-Y.C. performed the fabrication and characterization of the solar cells. X.D., J.Q., P.T.H., and A.M.B. co-wrote the paper and all authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Supporting Information. Supplementary discussion, supplementary materials and methods, supplementary figures, supplementary tables, and supplementary references. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Dang X, Yi H, Ham MH, Qi J, Yun DS, Ladewski R, Strano MS, Hammond PT, Belcher AM. Nature Nanotech. 2011;6(6):377–384. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qi J, Dang X, Hammond PT, Belcher AM. ACS Nano. 2011;5(9):7108–7116. doi: 10.1021/nn201808g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yella A, Lee HW, Tsao HN, Yi C, Chandiran AK, Nazeeruddin MK, Diau EWG, Yeh CY, Zakeeruddin SM, Grätzel M. Science. 2011;334(6056):629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.1209688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardin BE, Snaith HJ, McGehee MD. Nature Photon. 2012;6(3):162–169. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito S, Zakeeruddin SM, Comte P, Liska P, Kuang D, Grätzel M. Nature Photon. 2008;2(11):693–698. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagfeldt A, Boschloo G, Sun L, Kloo L, Pettersson H. Chem Rev. 2010;110(11):6595–6663. doi: 10.1021/cr900356p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung I, Lee B, He J, Chang RPH, Kanatzidis MG. Nature. 2012;485(7399):486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature11067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HS, Lee CR, Im JH, Lee KB, Moehl T, Marchioro A, Moon SJ, Humphry-Baker R, Yum JH, Moser JE, Grätzel M, Park NG. Sci Rep. 2012;2:591. doi: 10.1038/srep00591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yum JH, Baranoff E, Wenger S, Nazeeruddin MK, Grätzel M. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4(3):842–857. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nazeeruddin MK, Péchy P, Renouard T, Zakeeruddin SM, Humphry-Baker R, Comte P, Liska P, Cevey L, Costa E, Shklover V, Spiccia L, Deacon GB, Bignozzi CA, Grätzel M. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(8):1613–1624. doi: 10.1021/ja003299u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cid JJ, Yum JH, Jang SR, Nazeeruddin MK, Martínez-Ferrero E, Palomares E, Ko J, Grätzel M, Torres T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46(44):8358–8362. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardin BE, Hoke ET, Armstrong PB, Yum JH, Comte P, Torres T, Frechet JMJ, Nazeeruddin MK, Grätzel M, McGehee MD. Nature Photon. 2009;3(7):406–411. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atwater HA, Polman A. Nature Mater. 2010;9(3):205–213. doi: 10.1038/nmat2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown MD, Suteewong T, Kumar RSS, D’Innocenzo V, Petrozza A, Lee MM, Wiesner U, Snaith HJ. Nano Lett. 2010;11(2):438–445. doi: 10.1021/nl1031106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi H, Chen WT, Kamat PV. ACS Nano. 2012;6(5):4418–4427. doi: 10.1021/nn301137r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Blaber MG, Standridge SD, DeMarco EJ, Hupp JT, Ratner MA, Schatz GC. J Phys Chem C. 2012;116(18):10215–10221. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aydin K, Ferry VE, Briggs RM, Atwater HA. Nat Commun. 2011;2:517. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao H, Liu C, Jeong HE, Yang P. ACS Nano. 2011;6(1):234–240. doi: 10.1021/nn203457a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoud MA, Snyder B, El-Sayed MA. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114(16):7436–7443. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu M, Chen J, Li ZY, Au L, Hartland GV, Li X, Marquez M, Xia Y. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(11):1084–1094. doi: 10.1039/b517615h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodali AK, Llora X, Bhargava R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(31):13620–13625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003926107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milton GW, Nicorovici NAP, McPhedran RC, Podolskiy VA. Proc R Soc A. 2005;461(2064):3999–4034. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prodan E, Radloff C, Halas NJ, Nordlander P. Science. 2003;302(5644):419–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1089171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skrabalak SE, Chen J, Sun Y, Lu X, Au L, Cobley CM, Xia Y. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41(12):1587–1595. doi: 10.1021/ar800018v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanthil M, Thomas R, Swathi RS, George Thomas K. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3(11):1459–1464. doi: 10.1021/jz3004014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halme J, Vahermaa P, Miettunen K, Lund P. Adv Mater. 2010;22(35):E210–E234. doi: 10.1002/adma.201000726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takai A, Kamat PV. ACS Nano. 2011;5(9):7369–7376. doi: 10.1021/nn202294b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warren SC, Walker DA, Grzybowski BA. Langmuir. 2012;28(24):9093–9102. doi: 10.1021/la300377j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hägglund C, Apell SP. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3(10):1275–1285. doi: 10.1021/jz300290d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linic S, Christopher P, Ingram DB. Nature Mater. 2011;10(12):911–921. doi: 10.1038/nmat3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomann I, Pinaud BA, Chen Z, Clemens BM, Jaramillo TF, Brongersma ML. Nano Lett. 2011;11(8):3440–3446. doi: 10.1021/nl201908s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.