Abstract

AIM: To investigate insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) differentially methylated region (DMR)0 hypomethylation in relation to clinicopathological and molecular features in colorectal serrated lesions.

METHODS: To accurately analyze the association between the histological types and molecular features of each type of serrated lesion, we consecutively collected 1386 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens that comprised all histological types [hyperplastic polyps (HPs, n = 121), sessile serrated adenomas (SSAs, n = 132), traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs, n = 111), non-serrated adenomas (n = 195), and colorectal cancers (CRCs, n = 827)]. We evaluated the methylation levels of IGF2 DMR0 and long interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) in HPs (n = 115), SSAs (n = 120), SSAs with cytological dysplasia (n = 10), TSAs (n = 91), TSAs with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) (n = 15), non-serrated adenomas (n = 80), non-serrated adenomas with HGD (n = 105), and CRCs (n = 794). For the accurate quantification of the relative methylation levels (scale 0%-100%) of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1, we used bisulfite pyrosequencing method. Tumor specimens were analyzed for microsatellite instability, KRAS (codons 12 and 13), BRAF (V600E), and PIK3CA (exons 9 and 20) mutations; MLH1 and MGMT methylation; and IGF2 expression by immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS: The distribution of the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level in 351 serrated lesions and 185 non-serrated adenomas (with or without HGD) was as follows: mean 61.7, median 62.5, SD 18.0, range 5.0-99.0, interquartile range 49.5-74.4. The IGF2 DMR0 methylation level was divided into quartiles (Q1 ≥ 74.5, Q2 62.6-74.4, Q3 49.6-62.5, Q4 ≤ 49.5) for further analysis. With regard to the histological type, the IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels of SSAs (mean ± SD, 73.1 ± 12.3) were significantly higher than those of HPs (61.9 ± 20.5), TSAs (61.6 ± 19.6), and non-serrated adenomas (59.0 ± 15.8) (P < 0.0001). The IGF2 DMR0 methylation level was inversely correlated with the IGF2 expression level (r = -0.21, P = 0.0051). IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was less frequently detected in SSAs compared with HPs, TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas (P < 0.0001). Multivariate logistic regression analysis also showed that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was inversely associated with SSAs (P < 0.0001). The methylation levels of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 in TSAs with HGD (50.2 ± 18.7 and 55.7 ± 5.4, respectively) were significantly lower than those in TSAs (61.6 ± 19.6 and 58.8 ± 4.7, respectively) (IGF2 DMR0, P = 0.038; LINE-1, P = 0.024).

CONCLUSION: IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation may be an infrequent epigenetic alteration in the SSA pathway. Hypomethylation of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 may play a role in TSA pathway progression.

Keywords: BRAF, Colon polyp, Colorectal neoplasia, Colorectum, Genome, Insulin-like growth factor, Long interspersed nucleotide element-1, Microsatellite instability, Serrated pathway

Core tip: The serrated pathway attracts considerable attention as an alternative colorectal cancer (CRC) pathway. We previously reported the association of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) differentially methylated region (DMR)0 hypomethylation with prognosis and its link to LINE-1 hypomethylation in CRC; however, there have been no studies describing its role in the serrated pathway. Therefore, we evaluated the methylation levels of IGF2 DMR0 and long interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) in 351 serrated lesions and 185 non-serrated adenomas. Our results suggest that the IGF2 DMR0 may be an infrequent epigenetic alteration in the sessile serrated adenoma pathway. Moreover, we found that the hypomethylation of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 may play an important role in the progression of traditional serrated adenoma.

INTRODUCTION

The serrated neoplasia pathway has attracted considerable attention as an alternative pathway of colorectal cancer (CRC) development, and serrated lesions exhibit unique clinicopathological or molecular features[1-23]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification[24], colorectal premalignant (or non-malignant) neoplastic lesions with serrated morphology currently encompass three major categories: hyperplastic polyp (HP), sessile serrated adenoma (SSA), and traditional serrated adenoma (TSA).

SSA and TSA are premalignant lesions, but SSA is the principal serrated precursor of CRCs[15]. In particular, there are many clinicopathological and molecular similarities between SSA and microsatellite instability (MSI)-high CRC, for example, right-sided predilection, MLH1 hypermethylation, and frequent BRAF mutation[7,15,17-19,25-28]. Therefore, SSAs are hypothesized to develop in some cases to MSI-high CRCs with BRAF mutation in the proximal colon[7,15,17,25,26,28,29].

In contrast, TSAs are much less common than SSAs, and thus, there are fewer data on their molecular profile[15,25]. TSAs typically do not show MLH1 hypermethylation or develop to MSI-high CRCs, but they do commonly have MGMT hypermethylation[15,25,26]. With regard to the PIK3CA gene, a previous study reported that no mutation was found in serrated lesions, and that mutations were uncommonly, but exclusively, observed in non-serrated adenomas (1.4%)[30]. Because some HPs do share molecular features with TSAs (e.g., KRAS mutation)[3,25,26,31], it has been suggested that the TSA pathway (HP-TSA-carcinoma sequence) may diverge from the SSA pathway (HP-SSA-SSA with cytological dysplasia-carcinoma sequence) on the basis of KRAS vs BRAF mutations and/or MLH1 vs MGMT hypermethylation within subsets of HPs[15]. However, a definite precursor of TSA has not been established. In addition, the key carcinogenic mechanism involved in this TSA pathway remains largely unknown.

Loss of imprinting (LOI) of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of CRC[32,33], suggesting that it may play a role in colorectal carcinogenesis. The imprinting and expression of IGF2 are controlled by CpG-rich regions known as differentially methylated regions (DMRs)[34-37]. In particular, IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation has been suggested as a surrogate-biomarker for IGF2 LOI[38]. Previously, we reported that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in CRC was associated with poor prognosis and might be linked to global DNA hypomethylation [long interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) hypomethylation][38]. However, to date, there have been no studies describing the role of IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in the early stage of colorectal carcinogenesis.

To investigate the role of IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in serrated lesions we examined IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 methylation levels as well as other molecular alterations using a large sample of 1330 colorectal tumors (351 serrated lesions, 185 non-serrated adenomas, and 794 CRCs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Histopathological evaluation of tissue specimens of colorectal serrated lesions

Histological findings related to all colorectal serrated lesion specimens were evaluated by a pathologist (Fujita M) who was blinded to the clinical and molecular information. Serrated lesions (HPs, SSAs, and TSAs) were classified on the basis of the current WHO criteria[24]. HPs were further subdivided into microvesicular HPs and goblet cell HPs.

SSAs are characterized by the presence of a disorganized and distorted crypt growth pattern that is usually easily identifiable upon low-power microscopic examination. Crypts, particularly at the basal portion of the polyp, may appear architecturally distorted, dilated, and/or branched, particularly in the horizontal plane, which leads to the formation of boot, L, or anchor-shaped crypts. The cytology is typically quite bland, but a minor degree of nuclear atypia is allowable, particularly in the crypt bases[15,25,26].

To accurately analyze the association between the histological types and molecular features of each type of serrated lesion we consecutively collected more than 100 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens of each histological type (HP, SSA, and TSA). In total, 364 tissue specimens of serrated lesions [121 HPs, 122 SSAs, 10 SSAs with cytological dysplasia, 96 TSAs, and 15 TSAs with high-grade dysplasia (HGD)] from patients who underwent endoscopic resection or other surgical treatment at Sapporo Medical University Hospital, Keiyukai Sapporo Hospital or Teine-Keijinkai Hospital between 2001 and 2012 were available for assessment. All of HPs were microvesicular HPs.

The serrated lesions were classified by location: the proximal colon (cecum, ascending and transverse colon), distal colon (splenic flexure, descending, sigmoid colon) and rectum. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before specimen collection. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. The term “prognostic marker” is used throughout this article according to the REMARK Guidelines[39].

Tissue specimens of CRC and non-serrated adenomas

FFPE tissue specimens of 827 CRCs (stages I-IV), 85 non-serrated adenomas (i.e., tubular or tubulovillous adenomas), and 110 non-serrated adenomas with HGD from patients who underwent surgical treatment or endoscopic resection at the above hospitals were also collected. The criterion for diagnosing cancer was invasion of malignant cells beyond the muscularis mucosa.

DNA extraction and pyrosequencing for KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA and MSI analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the FFPE tissue specimens of the colorectal tumors using a QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States). PCR and targeted pyrosequencing were then performed using the extracted genomic DNA to determine the presence of KRAS (codons 12 and 13), BRAF (V600E) and PIK3CA (exons 9 and 20) mutations[40,41]. MSI analysis was performed as previously described using 10 microsatellite markers[14]. MSI-high was defined as instability in ≥ 30% of the markers and MSI-low/microsatellite stable (MSS) as instability in < 30% of the markers[14].

Sodium bisulfite treatment and pyrosequencing to measure IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 methylation levels

Bisulfite modification of genomic DNA was performed using a BisulFlash™ DNA Modification Kit (Epigentek, Brooklyn, NY, United States).

We measured the relative methylation level at the IGF2 DMR0 using a bisulfite-pyrosequencing assay as previously described[38]. The amount of C relative to the sum of the amounts of C and T at each CpG site was calculated as percentage (scale 0%-100%). We calculated the average of the first and second CpG sites in the IGF2 DMR0 as the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level. Likewise, to accurately quantify the LINE-1 methylation levels we utilized a pyrosequencing assay, as previously described[42].

Pyrosequencing to measure MGMT and MLH1 promoter methylation

Pyrosequencing for MGMT and MLH1 methylation was performed using the PyroMark kit (Qiagen). We used a previously defined cut-off of ≥ 8% methylated alleles for MGMT and MLH1 hypermethylated tumors[43].

Immunohistochemistry for IGF2 expression

For IGF2 staining, we used anti-IGF2 antibody (Rabbit polyclonal to IGF2; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States) with a subsequent reaction performed using Target Retrieval Solution, Citrate pH 6 (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA, United States). In each case, we recorded cytoplasmic IGF2 expression as no expression, weak expression, moderate expression, or strong expression relative to normal colorectal epithelial cells. IGF2 expression was visually interpreted by Nosho K, who was unaware of the other data. For the agreement study of IGF2 expression, 128 randomly selected cases were examined by a second pathologist (by Naito T), who was also unaware of the other data. The concordance between the two pathologists (P < 0.0001) was 0.84 (κ = 0.69), indicating substantial agreement.

Statistical analysis

JMP (version 10) software was used for all statistical analyses (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). All P values were two-sided. Univariate analyses were performed to investigate the clinicopathological and molecular characteristics including IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 hypomethylation, according to histological type, classified as serrated lesion, non-serrated adenoma, and CRC. P values were calculated by analysis of variance for age, tumor size, and the methylation levels of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 and by χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for all other variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to examine associations with IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation (as an outcome variable), adjusting for potential confounders. The model initially included sex, age, tumor size, tumor location, histological type, and the LINE-1 methylation level, and MSI, BRAF, KRAS, and PIK3CA mutations. In the CRC-specific survival analysis, the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to assess the survival time distribution. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation of the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level and IGF2 expression.

RESULTS

The IGF2 DMR0 methylation level in serrated lesion and non-serrated adenomas

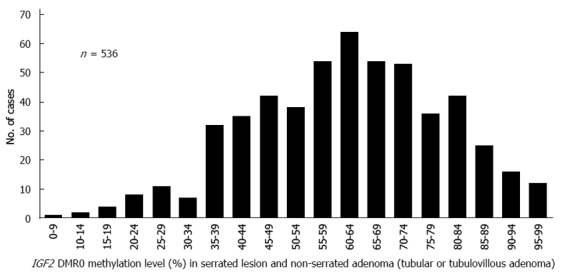

We assessed 559 FFPE tissue specimens of serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas in the IGF2 DMR0 methylation assay and obtained 536 (96%) valid results. The distribution of the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level in 351 serrated lesions and 185 non-serrated adenomas (with or without HGD) was as follows: mean 61.7, median 62.5, SD 18.0, range 5.0-99.0, interquartile range 49.5-74.4 (all on a 0-100 scale) (Figure 1). The IGF2 DMR0 methylation level was divided into quartiles (Q1 ≥ 74.5, Q2 62.6-74.4, Q3 49.6-62.5, Q4 ≤ 49.5) for further analysis.

Figure 1.

Distribution of IGF2 differentially methylated region 0 methylation levels in 351 serrated lesions. Hyperplastic polyp, sessile serrated adenoma (SSA), SSA with cytological dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) and TSA with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and 185 non-serrated adenomas (tubular adenoma, tubular adenoma with HGD, tubulovillous adenoma and tubulovillous adenoma with HGD). DMR: Differentially methylated region; IGF2: Insulin-like growth factor 2.

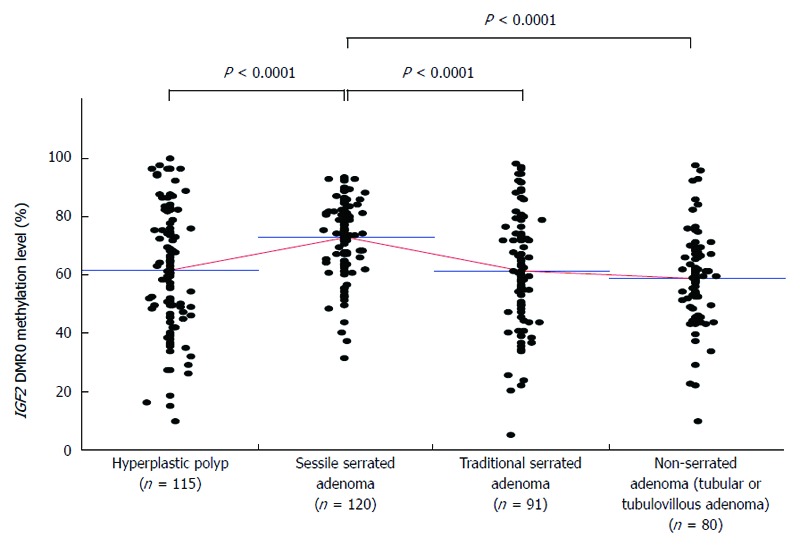

We evaluated the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level in serrated lesions (HP, SSA, and TSA) and non-serrated adenomas according to their histological type. The IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels of SSAs (n = 120, mean ± SD, 73.1 ± 12.3) were significantly higher than those of HPs (n = 115, 61.9 ± 20.5, P < 0.0001), TSAs (n = 91, 61.6 ± 19.6, P < 0.0001), and non-serrated adenomas (n = 80, 59.0 ± 15.8, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

IGF2 differentially methylated region 0 methylation level according to histological type. Insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) differentially methylated region (DMR)0 methylation levels of sessile serrated adenoma (mean ± SD; 73.1 ± 12.3) were significantly higher compared with those of hyperplastic polyp (61.9 ± 20.5, P < 0.0001), traditional serrated adenoma (61.6 ± 19.6, P < 0.0001), and non-serrated adenoma (59.0 ± 15.8, P < 0.0001). P-values were calculated by analysis of variance.

IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was associated with larger tumor size in serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas (Table 1). With regard to the histological type, IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was less frequently detected in SSAs than in HPs, TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas (P < 0.0001) (Table 1). Multivariate logistic regression analysis also showed the IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was inversely associated with SSAs (P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

IGF2 differentially methylated region 0 hypomethylation in serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas n (%)

| Clinicopathological feature | Total n |

IGF2 DMR0 methylation (quartile) |

P value | |||

| Q1 (≥ 74.5) | Q2 (62.6-74.4) | Q3 (49.6-62.5) | Q4 (≤ 49.5) | |||

| All cases | 536 | 134 | 130 | 131 | 141 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 326 (61) | 78 (58) | 80 (62) | 92 (70) | 76 (54) | 0.041 |

| Female | 210 (39) | 56 (42) | 50 (38) | 39 (30) | 65 (46) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 61.5 ± 12.2 | 59.9 ± 12.3 | 60.8 ± 12.0 | 63.1 ± 11.6 | 62.3 ± 13.0 | 0.150 |

| Tumor size (mm) (mean ± SD) | 14.3 ± 11.4 | 9.9 ± 4.0 | 13.4 ± 7.4 | 14.7 ± 11.1 | 19.1 ± 17.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Rectum | 70 (13) | 11 (8.5) | 14 (11) | 18 (14) | 27 (20) | 0.061 |

| Distal colon | 161 (31) | 35 (27) | 43 (33) | 37 (29) | 46 (33) | |

| Proximal colon | 296 (56) | 84 (65) | 72 (56) | 75 (58) | 65 (47) | |

| Histological type | ||||||

| Hyperplastic polyp (HP) | 115 (21) | 33 (25) | 25 (19) | 23 (18) | 34 (24) | < 0.0001 |

| Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) without cytological dysplasia | 120 (22) | 60 (45) | 39 (30) | 15 (11) | 6 (4.3) | |

| SSA with cytological dysplasia | 10 (1.9) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.3) | 6 (4.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) without high-grade dysplasia (HGD) | 91 (17) | 22 (16) | 21 (16) | 23 (18) | 25 (18) | |

| TSA with HGD | 15 (2.8) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 9 (6.4) | |

| Non-serrated adenoma (tubular or tubulovillous adenoma) without HGD | 80 (15) | 11 (8.2) | 17 (13) | 32 (24) | 20 (14) | |

| Non-serrated adenoma with HGD | 105 (20) | 5 (3.7) | 23 (18) | 30 (23) | 47 (33) | |

Percentage indicates the proportion of patients of each histological type who met the criteria for a specific clinical or molecular feature. P values were calculated by analysis of variance for age and tumor size and by χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for all other variables. The P value for significance was adjusted by Bonferroni correction to 0.010 (= 0.05/5).

Association of IGF2 expression and IGF2 DMR0 methylation level in serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas

We examined IGF2 overexpression in 168 colorectal serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas. The IGF2 DMR0 methylation level was inversely correlated with the IGF2 expression level (r = -0.21, P = 0.0051).

IGF2 DMR0 methylation level in colorectal cancer

A total of 827 paraffin-embedded CRCs (stages I-IV) were subjected to an IGF2 DMR0 methylation assay with 794 (96%) valid results. The distribution of the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level in these 794 CRCs was as follows: mean 54.7, median 55.0, SD 13.7, range 7.5-98.0, interquartile range 46.1-63.0 (all on a 0-100 scale). The IGF2 DMR0 methylation level was divided into quartiles (Q1 ≥ 63.0, Q2 55.0-62.9, Q3 46.1-54.9, Q4 ≤ 46.0) for further analysis.

Colorectal cancer patient survival and IGF2 DMR0 methylation level

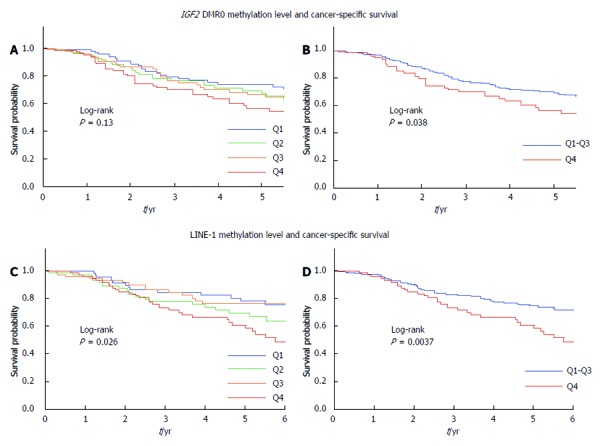

The influence of the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level on clinical outcome was assessed in CRC patients. During the follow-up of 398 patients with metastatic CRC (stages III-IV) who were eligible for survival analysis, mortality occurred in 134, including 118 deaths confirmed to be attributable to CRC. The median follow-up period for censored patients was 3.3 years. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed using categorical variables (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4). Slightly but insignificantly higher mortality was observed in patients with IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation compared with those without hypomethylation in terms of cancer-specific survival (log-rank test: P = 0.13) (Figure 3A). In another Kaplan-Meier analysis, Q4 cases were defined as the “hypomethylated group” and the Q1, Q2, and Q3 cases were combined into a “non-hypomethylated group”; the hypomethylated group (log-rank test: P = 0.038) was found to have significantly higher mortality (Figure 3B). Similar results were observed in terms of overall survival (log-rank test: P = 0.040) (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for colorectal cancer according to the IGF2 differentially methylated region 0 and long interspersed nucleotide element-1 methylation levels in metastatic colorectal cancers. A: Patients with Insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) differentially methylated region (DMR)0 hypomethylation had a slightly higher mortality rate than those with IGF2 DMR0 hypermethylation, but this difference was not significant (log-rank test: P = 0.13); B: IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation (Q4 cases) was significantly associated with unfavorable cancer-specific survival (log-rank test: P = 0.038); C: Significantly higher mortality was observed in patients with long interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) hypomethylation compared with those with LINE-1 hypermethylation (log-rank test: P = 0.026); D: LINE-1 hypomethylation (Q4 cases) was significantly associated with unfavorable cancer-specific survival (log-rank test: P = 0.0037).

LINE-1 methylation level and CRC patient survival

The LINE-1 methylation level in CRC was also divided into quartiles (Q1 ≥ 58.7, Q2 54.8-58.6, Q3 50.8-54.7, and Q4 ≤ 50.7). A significantly higher mortality rate was observed among Q4 cases (log-rank test: P = 0.0037) in the Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 3C, D).

Association of histological type and IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 methylation levels as well as other molecular features of serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas

Table 2 shows the clinicopathological and molecular features of serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas. No significant difference was observed between SSAs (69.0 ± 10.8) with cytological dysplasia and SSAs without (73.1 ± 12.3) in IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels (P = 0.32). In contrast, MSI-high was more frequently (P < 0.0001) found in SSAs with cytological dysplasia [40% (4/10)] than in SSAs [0.8% (1/120)]. With regard to the LINE-1 methylation level, no significant difference was observed between the methylation level and histological type in serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas (P = 0.59).

Table 2.

Clinical and molecular features of serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas (tubular or tubulovillous adenoma) according to histological type n (%)

| Clinical or molecular feature | Total n |

Histological type |

P value | |||||

|

Serrated lesion |

Non-serrated adenoma |

|||||||

| HP | SSA without cytological dysplasia | SSA with cytological dysplasia | TSA without high-grade dysplasia (HGD) | Tubular adenoma without HGD | Tubulovillous adenoma without HGD | |||

| All cases | 416 | 115 | 120 | 10 | 91 | 77 | 3 | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 263 (63) | 78 (68) | 72 (60) | 5 (50) | 55 (60) | 50 (65) | 3 (100) | 0.36 |

| Female | 153 (37) | 37 (32) | 48 (40) | 5 (50) | 36 (40) | 27 (35) | 0 (0) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 60.3 ± 11.8 | 57.5 ± 12.1 | 57.2 ± 11.6 | 74.1 ± 4.7 | 60.9 ± 12.3 | 66.6 ± 11.4 | 66.0 ± 8.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 10.5 ± 5.4 | 9.3 ± 3.7 | 11.6 ± 5.4 | 12.3 ± 6.4 | 9.7 ± 4.7 | 10.9 ± 7.2 | 15.7 ± 13.2 | 0.0069 |

| (mean ± SD) | ||||||||

| Tumor location | ||||||||

| Rectum | 42 (10) | 15 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (18) | 10 (14) | 1 (33) | < 0.0001 |

| Distal colon | 127 (31) | 44 (39) | 17 (14) | 1 (10) | 39 (44) | 25 (34) | 1 (33) | |

| Proximal colon | 239 (59) | 54 (48) | 103 (86) | 9 (90) | 34 (38) | 38 (52) | 1 (33) | |

| BRAF mutation | ||||||||

| Wild-type | 183 (44) | 59 (51) | 16 (13) | 2 (20) | 28 (31) | 75 (97) | 3 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| Mutant | 231 (55) | 56 (49) | 104 (87) | 8 (80) | 61 (69) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | |

| KRAS mutation | ||||||||

| Wild-type | 357 (87) | 92 (81) | 117 (98) | 10 (100) | 74 (83) | 62 (81) | 2 (67) | < 0.0001 |

| Mutant | 55 (13) | 21 (19) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 15 (17) | 15 (19) | 1 (33) | |

| PIK3CA mutation | ||||||||

| Wild-type | 406 (99) | 113 (99) | 117 (100) | 10 (100) | 89 (100) | 74 (99) | 3 (100) | 0.67 |

| Mutant | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| MSI status | ||||||||

| MSS/MSI-low | 408 (98) | 113 (98) | 119 (99) | 6 (60) | 90 (99) | 77 (100) | 3 (100) | 0.0004 |

| MSI-high | 8 (1.9) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (40) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| IGF2 DMR0 | 64.5 ± 17.2 | 61.9 ± 20.5 | 73.1 ± 12.3 | 69.0 ± 10.8 | 61.6 ± 19.6 | 58.9 ± 16.1 | 61.0 ± 7.1 | < 0.0001 |

| methylation level (mean ± SD) | ||||||||

| LINE-1 | 58.7 ± 5.0 | 58.6 ± 3.4 | 58.1 ± 5.4 | 58.3 ± 8.4 | 58.8 ± 4.7 | 59.4 ± 6.0 | 60.9 ± 1.4 | 0.59 |

| methylation level (mean ± SD) | ||||||||

Percentage indicates the proportion of patients of each histological type who met the criteria for a specific clinical or molecular feature. P values were calculated by analysis of variance for age, tumor size, methylation levels of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 and by χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for all other variables. The P value for significance was adjusted by Bonferroni correction to 0.0050 (= 0.05/10). HGD: High-grade dysplasia; HP: Hyperplastic polyp; MSI: Microsatellite instability; MSS: Microsatellite stable; SSA: Sessile serrated adenoma; TSA: Traditional serrated adenoma; IGF2: Insulin-like growth factor 2.

Mutations of BRAF, KRAS, and PIK3CA were detected in 49%, 19%, and 0.9% of HPs, 87%, 2.5%, and 0% of SSAs, 69%, 17%, and 0% of TSAs and 2.6%, 19%, and 1.3% of non-serrated adenomas, respectively (Table 2).

IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 hypomethylation in TSAs and non-serrated adenomas with high-grade dysplasia

Tables 3 and 4 show the clinicopathological and molecular features of the TSAs (with or without HGD), non-serrated adenomas (with or without HGD), and CRCs (stages I-IV). The IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels in TSAs with HGD (50.2 ± 18.7) were significantly lower than those in TSAs without (61.6 ± 19.6, P = 0.038) (Table 3). With regard to LINE-1, the methylation levels in TSAs with HGD (55.7 ± 5.4) were significantly lower than those in TSAs without (58.8 ± 4.7) (P = 0.024).

Table 3.

Clinical and molecular features of sessile serrated adenomas with cytological dysplasia, traditional serrated adenomas, non-serrated adenomas (tubular or tubulovillous adenoma), and colorectal carcinomas according to disease stage n (%)

| Clinical or molecular feature |

Histological type |

P value | ||||||||

| SSA with cytological dysplasia |

Colorectal adenoma |

Colorectal carcinoma |

||||||||

| TSA without HGD | TSA with HGD | Non-serrated adenoma without HGD | Non-serrated adenoma with HGD | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | |||

| All cases | 10 | 91 | 15 | 80 | 105 | 171 | 217 | 292 | 114 | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 5 (50) | 55 (60) | 9 (60) | 53 (66) | 54 (51) | 107 (63) | 123 (57) | 168 (58) | 73 (64) | 0.50 |

| Female | 5 (50) | 36 (40) | 6 (40) | 27 (34) | 51 (49) | 64 (37) | 94 (43) | 124 (42) | 41 (36) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 74.1 ± 4.7 | 60.9 ± 12.3 | 62.7 ± 13.6 | 66.6 ± 11.2 | 66.3 ± 10.5 | 65.1 ± 11.0 | 67.4 ± 11.5 | 66.6 ± 12.5 | 63.4 ± 9.5 | 0.0016 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 12.3 ± 6.4 | 9.7 ± 4.7 | 12.8 ± 4.3 | 11.0 ± 7.4 | 29.3 ± 17.3 | 26.3 ± 15.8 | 53.1 ± 23.5 | 50.5 ± 22.7 | 50.9 ± 19.6 | < 0.0001 |

| (mean ± SD) | ||||||||||

| Tumor location | ||||||||||

| Rectum | 0 (0) | 16 (18) | 5 (33) | 11 (14) | 23 (22) | 65 (38) | 73 (34) | 135 (46) | 37 (33) | < 0.0001 |

| Distal colon | 1 (10) | 39 (44) | 7 (47) | 26 (34) | 27 (26) | 44 (25) | 64 (29) | 59 (20) | 42 (37) | |

| Proximal colon | 9 (90) | 34 (38) | 3 (20) | 39 (51) | 54 (52) | 62 (36) | 80 (37) | 98 (34) | 34 (30) | |

| BRAF mutation | ||||||||||

| Wild-type | 2 (20) | 28 (31) | 7 (47) | 78 (98) | 102 (98) | 161 (95) | 204 (94) | 282 (97) | 103 (95) | < 0.0001 |

| Mutant | 8 (80) | 61 (69) | 8 (53) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (1.9) | 9 (5.3) | 13 (6.0) | 9 (3.0) | 6 (5.5) | |

| KRAS mutation | ||||||||||

| Wild-type | 10 (100) | 74 (83) | 11 (73) | 64 (80) | 48 (46) | 108 (64) | 145 (69) | 202 (70) | 84 (74) | < 0.0001 |

| Mutant | 0 (0) | 15 (17) | 4 (27) | 16 (20) | 57 (54) | 62 (36) | 66 (31) | 88 (30) | 29 (26) | |

| PIK3CA mutation | ||||||||||

| Wild-type | 10 (100) | 89 (100) | 14 (93) | 77 (99) | 99 (94) | 161 (94) | 194 (89) | 249 (85) | 103 (90) | < 0.0001 |

| Mutant | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (1.3) | 6 (5.7) | 10 (5.9) | 23 (11) | 43 (15) | 11 (9.7) | |

| MSI status | ||||||||||

| MSS/MSI-low | 6 (60) | 90 (99) | 15 (100) | 80 (100) | 105 (100) | 163 (95) | 198 (91) | 276 (95) | 110 (96) | < 0.0001 |

| MSI-high | 4 (40) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (4.7) | 19 (8.8) | 16 (5.5) | 4 (3.5) | |

| IGF2 DMR0 | 69.0 ± 10.8 | 61.6 ± 19.6 | 50.2 ± 18.7 | 59.0 ± 15.8 | 52.0 ± 13.6 | 55.7 ± 15.8 | 53.4 ± 13.3 | 55.5 ± 12.9 | 53.1 ± 12.9 | < 0.0001 |

| methylation level (mean ± SD) | ||||||||||

| LINE-1 | 58.3 ± 8.4 | 58.8 ± 4.7 | 55.7 ± 5.4 | 59.5 ± 5.9 | 56.9 ± 5.5 | 55.8 ± 7.2 | 53.1 ± 6.2 | 55.1 ± 6.5 | 54.1 ± 7.6 | < 0.0001 |

| methylation level (mean ± SD) | ||||||||||

Percentage indicates the proportion of patients of each histological type who met the criteria for a specific clinical or molecular feature. P values were calculated by analysis of variance for age, tumor size, methylation levels of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 and by χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for all other variables. The P value for significance was adjusted by Bonferroni correction to 0.0050 (= 0.05/10). HGD: High-grade dysplasia; HP: Hyperplastic polyp; MSI: Microsatellite instability; MSS: Microsatellite stable; SSA: Sessile serrated adenoma; TSA: Traditional serrated adenoma; IGF2: Insulin-like growth factor 2.

Table 4.

Clinicopathological and molecular features of fifteen traditional serrated adenomas with high-grade dysplasia

| No. | Age/sex | Location | Size (mm) | KRAS mutation | BRAF mutation | PIK3CA mutation | MGMT methylation | MLH1 methylation | MSI status | LINE-1 methylation level | IGF2 DMR0 methylation level | IGF2 expression |

| 1 | 75/M | Rectum | 8 | c.35G>A (p.G12D) | Wild | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 58 | 70 | Weak |

| 2 | 54/F | Sigmoid colon | 20 | c.35G>A (p.G12D) | Wild | Wild | (+) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 53.7 | 39.5 | Strong |

| 3 | 62/F | Transverse colon | 15 | c.38G>A (p.G13D) | Wild | Wild | (+) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 53.3 | 72.0 | No expression |

| 4 | 84/M | Rectum | 5 | c.35G>A (p.G12D) | Wild | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 65.0 | 26.5 | Moderate |

| 5 | 85/M | Sigmoid colon | 12 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 58.0 | 45.5 | Strong |

| 6 | 48/M | Sigmoid colon | 20 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 53.7 | 40.5 | Moderate |

| 7 | 69/M | Sigmoid colon | 10 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 58.7 | 52.0 | No expression |

| 8 | 60/M | Descending colon | 9 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 59.0 | 41.5 | Moderate |

| 9 | 34/M | Sigmoid colon | 18 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (+) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 57.3 | 42.0 | Strong |

| 10 | 61/M | Rectum | 10 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 56.7 | 29.0 | Strong |

| 11 | 52/F | Ascending colon | 15 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (+) | (+) | MSS/MSI-low | 57.0 | 57.0 | Moderate |

| 12 | 70/F | Rectum | 13 | Wild | c.1799T>A (p.V600E) | Wild | (+) | (+) | MSS/MSI-low | 63.0 | 84.5 | Weak |

| 13 | 66/F | Ascending colon | 12 | Wild | Wild | c.1624G>A (p.E542K) | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 49.7 | 28.0 | Moderate |

| 14 | 52/M | Sigmoid colon | 12 | Wild | Wild | Wild | (-) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 48.0 | 44.5 | Moderate |

| 15 | 69/F | Rectum | 13 | Wild | Wild | Wild | (+) | (-) | MSS/MSI-low | 44.3 | 80.0 | Weak |

HGD: High-grade dysplasia; MSI: Microsatellite instability; MSS: Microsatellite stable; TSA: Traditional serrated adenoma.

Similarly, the methylation levels of IGF2 DMR0 (52.0 ± 13.6) and LINE-1 (56.9 ± 5.5) in non-serrated adenomas with HGD were significantly lower than those in non-serrated adenomas without (59.0 ± 15.8, P = 0.0016 and 59.5 ± 5.9, P = 0.0027, respectively) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 methylation levels as well as other molecular alterations in 351 serrated lesions, 185 non-serrated adenomas, and 794 CRCs. IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was less frequently detected in SSAs than in HPs, TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas. We also found that IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 hypomethylation in TSAs and non-serrated adenomas with HGD were more frequently detected in TSAs and non-serrated adenomas without HGD, suggesting that hypomethylation may play an important role in the progression of these tumors.

In the current study, we confirmed that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was associated with poor CRC prognosis, suggesting its oncogenic role and malignant potential. In addition, our data showed that the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level was inversely correlated with the IGF2 expression level. Therefore, our findings support the validity of the quantitative DNA methylation assay (bisulfite-pyrosequencing) for examining the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level.

HPs are classified into three subtypes, namely microvesicular HPs, goblet cell HPs, and mucin-poor HPs. Microvesicular and goblet cell HPs are the most common, whereas mucin-poor HPs are rare[44]. Recent studies have reported that microvesicular HPs may be a precursor lesion of SSAs and that borderline lesions between microvesicular HPs and SSAs can occur[25,26,28]. In the current study, we found that the IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels of SSAs were significantly higher compared with those of HPs (microvesicular HPs), TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas. Our data also showed that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was less frequently detected in SSAs compared with HPs, TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas.

Our current study had some limitations due to its cross-sectional nature and the fact that unknown bias (i.e., selection bias) may confound the results. Nevertheless, our multivariate regression analysis was adjusted for potential confounders including age, tumor size, tumor location, LINE-1 methylation level, and BRAF and KRAS mutation. The results demonstrate that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation is inversely associated with SSAs. Moreover, our data have shown that the IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels of SSAs with cytological dysplasia were higher than those of HPs, suggesting that HPs (microvesicular HPs) or SSAs with IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation may tend not to progress to the typical SSA pathway [HP-SSA-SSA with cytological dysplasia-carcinoma (MSI-high) sequence] but to the alternate pathway. Thus, our finding of differential patterns of IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in serrated lesions may be a clue for elucidating the differentiation of serrated lesions.

In the current study, IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was found in TSAs and hypomethylation was more frequently detected in TSAs with HGD when compared with TSAs without HGD. These results may imply that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation can occur in the early stage of the TSA pathway and that TSAs with IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation are precursor lesions that progress to TSAs with HGD or CRCs with hypomethylation. In other words, TSAs without IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation may tend not to progress to TSAs with HGD. Otherwise, TSAs without IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation may tend to rapidly develop to CRCs; therefore, they are infrequently detected in the stage of TSA with HGD. However, because the number of TSA with HGD samples was small (n = 15), our findings require further confirmation from future independent studies.

Global DNA hypomethylation is associated with genomic instability, which leads to cancer[45-50]. As the LINE-1 or L1 retrotransposon constitutes a substantial portion (ca. 17%) of the human genome, the level of LINE-1 methylation is regarded as a surrogate marker of global DNA methylation[46,51]. We previously reported that LINE-1 methylation is highly variable but is strongly associated with a poor prognosis in CRC[45]. However, no previous study has reported the role of LINE-1 hypomethylation in serrated lesions. In serrated lesions, unlike the IGF2 DMR0 methylation level, no significant difference was observed between the LINE-1 methylation level and histological type. We also found that the LINE-1 methylation levels in TSAs with HGD were significantly lower than those in TSAs. These results suggest that both IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation and LINE-1 hypomethylation are important epigenetic alterations in the progression of TSAs. Because the carcinogenic mechanism remains unclear, further analyses are needed to clarify the role in the TSA pathway of the hypomethylation of these locations.

Previous studies have reported that SSAs with cytological dysplasia have accumulated genetic abnormalities and are at a high risk of progression to colorectal carcinoma[7,26,28]. Loss of staining for MLH1 leads to MSI and repeat tract mutation in genes such as TGFβRII is restricted to lesions with cytological dysplasia in SSAs[26,27,52,53]. In the current study, MSI-high was more frequently detected in SSAs with cytological dysplasia than in SSAs without. Our data indicate that in SSAs with cytological dysplasia, it is not hypomethylation of IGF2 DMR0 or LINE-1 but rather MSI due to MLH1 hypermethylation that plays an important role in the evolution to colorectal carcinoma.

The RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway is commonly altered in CRC and serrated lesions through oncogenic mutation of either BRAF or KRAS[15,21,25]. Moreover, CRCs with serrated morphology are particularly prone to mutations targeted by anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy. Therefore, as the variety of molecularly targeted agents for CRC increases, understanding of molecular alterations is becoming increasingly important[21,40]. BRAF and KRAS mutations are mutually exclusive and demonstrate a subtype specificity in serrated lesions[10,15,17-19,28]; they are most likely initiating events in the majority of HPs[54]. Previous studies have reported that BRAF is mutated with increasing frequency in SSAs (60%-100%)[3-5,9,11,16]. In the current study, BRAF mutations were detected in 49% of HPs and 87% of SSAs, respectively. Therefore, our data relating to the frequency of BRAF mutations in SSAs are consistent with previous reports. The activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway by BRAF or KRAS mutation is also common in TSAs. Previous studies have reported BRAF mutation rates in TSAs ranging from 27% to 55%[6,8,16,55], compared to KRAS mutation rates of 29%-46%[6,8]. In the current study, BRAF and KRAS mutations were detected in 69% and 17% of TSAs, respectively. Thus, the wide variation in the relative proportion of BRAF vs KRAS mutations in different studies reflects differences in histological classification or small sample size.

In conclusion, we found that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation can occur in the early stage of any histological types of serrated lesions; however, hypomethylation may be an infrequent epigenetic alteration in SSAs. These results imply that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation may be a key epigenetic event that affects the progression of HPs. Our data also suggest that the hypomethylation of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 may play an important role in the progression of the TSA pathway.

COMMENTS

Background

The serrated pathway attracts considerable attention as an alternative colorectal cancer (CRC) pathway. Authors previously reported the association of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) differentially methylated region (DMR)0 hypomethylation with poor prognosis and its link to global DNA hypomethylation [long interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) hypomethylation] in CRC; however, to date, there have been no studies describing its role in the serrated pathway.

Research frontiers

Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) and traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) are premalignant lesions, but SSA is the principal serrated precursor of CRC. In particular, there are many clinicopathological and molecular similarities between SSA and microsatellite instability (MSI)-high CRC, for example, right-sided predilection, MLH1 hypermethylation, and frequent BRAF mutation. Therefore, SSAs are hypothesized to develop in some cases to MSI-high CRCs with BRAF mutation in the proximal colon. In contrast, a definite precursor of TSA has not been established. In addition, the key carcinogenic mechanism involved in this TSA pathway remains largely unknown. To investigate the role of IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in serrated lesions they examined IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels as well as other molecular alterations.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first report of an association between histopathological findings and IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in serrated lesions. IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was less frequently detected in SSAs than in hyperplastic polyps (HPs), TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas. They also found that IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 hypomethylations in TSAs and non-serrated adenomas with high-grade dysplasia were more frequently detected in TSAs and non-serrated adenomas, suggesting that such hypomethylation may play an important role in the progression of those tumors. Thus, their finding of differential patterns of IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation in serrated lesions may be a clue for elucidating the progression of serrated lesions.

Applications

In the current study, authors found that the IGF2 DMR0 methylation levels of SSAs were significantly higher compared with those of HPs (microvesicular HPs), TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas. They also showed that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation was less frequently detected in SSAs compared with HPs, TSAs, and non-serrated adenomas. Therefore, their data challenge the common conception of discrete molecular features of SSAs vs other serrated lesions (TSAs and HPs) and may have a substantial impact on clinical and translational research, which has typically been performed with the dichotomous classification of SSAs.

Terminology

IGF2 DMR: IGF2 expression is controlled by CpG-rich regions known as IGF2 DMRs in CRC. In particular, IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation has been suggested as a surrogate-biomarker for IGF2 loss of imprinting. LINE-1: Global DNA hypomethylation is associated with genomic instability, which leads to cancer. As the long interspersed nucleotide element-1 or L1 retrotransposon constitutes a substantial portion of the human genome, the level of LINE-1 methylation is regarded as a surrogate marker of global DNA methylation. Serrated pathway: The serrated neoplasia pathway has attracted considerable attention as an alternative pathway of CRC development, and serrated lesions exhibit unique clinicopathological or molecular features. Of the serrated lesions, SSAs are hypothesized to develop in some cases to MSI-high CRCs with BRAF mutation in the proximal colon.

Peer review

The authors investigated the hypomethylations of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1; MSI; and mutations of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA in patients with serrated lesions and non-serrated adenomas. The results demonstrated that IGF2 DMR0 hypomethylation can occur in the early stage of any histological types of serrated lesions; however, hypomethylation may be an infrequent epigenetic alteration in SSAs. The authors also revealed that the hypomethylation of IGF2 DMR0 and LINE-1 may play an important role in the progression of the TSA pathway. This article may have a substantial impact on clinical and translational research in the progression of serrated lesions related to malignant transformation.

Footnotes

Supported by The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research, grant No. 23790800 (to Nosho K) and 23390200 (to Shinomura Y); A-STEP (Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through Target-driven R and D) (to Nosho K); Daiwa Securities Health Foundation (to Nosho K); Kobayashi Foundation for Cancer Research (to Nosho K); Sagawa Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research (to Nosho K); Suzuken Memorial Foundation (to Nosho K), and Takeda Science Foundation (to Nosho K); and USA National Institute of Health, grant number R01 CA151993 (to Ogino S)

P- Reviewer: Pescatori M, Yoshimatsu K S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Guarinos C, Sánchez-Fortún C, Rodríguez-Soler M, Alenda C, Payá A, Jover R. Serrated polyposis syndrome: molecular, pathological and clinical aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2452–2461. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i20.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelstein DL, Axilbund JE, Hylind LM, Romans K, Griffin CA, Cruz-Correa M, Giardiello FM. Serrated polyposis: rapid and relentless development of colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 2013;62:404–408. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spring KJ, Zhao ZZ, Karamatic R, Walsh MD, Whitehall VL, Pike T, Simms LA, Young J, James M, Montgomery GW, et al. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas with BRAF mutations: a prospective study of patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1400–1407. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr NJ, Mahajan H, Tan KL, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Serrated and non-serrated polyps of the colorectum: their prevalence in an unselected case series and correlation of BRAF mutation analysis with the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:516–518. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.061960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yachida S, Mudali S, Martin SA, Montgomery EA, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Beta-catenin nuclear labeling is a common feature of sessile serrated adenomas and correlates with early neoplastic progression after BRAF activation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1823–1832. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b6da19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KM, Lee EJ, Kim YH, Chang DK, Odze RD. KRAS mutations in traditional serrated adenomas from Korea herald an aggressive phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:667–675. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d40cb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita K, Yamamoto H, Matsumoto T, Hirahashi M, Gushima M, Kishimoto J, Nishiyama K, Taguchi T, Yao T, Oda Y. Sessile serrated adenoma with early neoplastic progression: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:295–304. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318205df36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu B, Yachida S, Morgan R, Zhong Y, Montgomery EA, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Clinicopathologic and genetic characterization of traditional serrated adenomas of the colon. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:356–366. doi: 10.1309/AJCPVT7LC4CRPZSK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi M, Kristensen MH, Nielsen HJ, Bonde JH, Holck S. Qualities of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp/lesion and its borderline variant in the context of synchronous colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:924–927. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosty C, Buchanan DD, Walsh MD, Pearson SA, Pavluk E, Walters RJ, Clendenning M, Spring KJ, Jenkins MA, Win AK, et al. Phenotype and polyp landscape in serrated polyposis syndrome: a series of 100 patients from genetics clinics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:876–882. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824e133f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaji E, Uraoka T, Kato J, Hiraoka S, Suzuki H, Akita M, Saito S, Tanaka T, Ohara N, Yamamoto K. Externalization of saw-tooth architecture in small serrated polyps implies the presence of methylation of IGFBP7. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1261–1270. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-2008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiraoka S, Kato J, Fujiki S, Kaji E, Morikawa T, Murakami T, Nawa T, Kuriyama M, Uraoka T, Ohara N, et al. The presence of large serrated polyps increases risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1503–1510, 1510.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Phipps AI, Passarelli MN, Grady WM, Upton MP, Zhu LC, Potter JD. Colorectal endoscopy, advanced adenomas, and sessile serrated polyps: implications for proximal colon cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1213–1219. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nosho K, Kure S, Irahara N, Shima K, Baba Y, Spiegelman D, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. A prospective cohort study shows unique epigenetic, genetic, and prognostic features of synchronous colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1609–1620.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Batts KP, Burke CA, Burt RW, Goldblum JR, Guillem JG, Kahi CJ, Kalady MF, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1315–1329; quiz 1314, 1330. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Potter JD, Passarelli MN, Phipps AI, Wurscher MA, Grady WM, Zhu LC, Upton MP, Makar KW. Genomic aberrations occurring in subsets of serrated colorectal lesions but not conventional adenomas. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2863–2872. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil DT, Shadrach BL, Rybicki LA, Leach BH, Pai RK. Proximal colon cancers and the serrated pathway: a systematic analysis of precursor histology and BRAF mutation status. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1423–1431. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kriegl L, Neumann J, Vieth M, Greten FR, Reu S, Jung A, Kirchner T. Up and downregulation of p16(Ink4a) expression in BRAF-mutated polyps/adenomas indicates a senescence barrier in the serrated route to colon cancer. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1015–1022. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mesteri I, Bayer G, Meyer J, Capper D, Schoppmann SF, von Deimling A, Birner P. Improved molecular classification of serrated lesions of the colon by immunohistochemical detection of BRAF V600E. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:135–144. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaiser T, Meinhardt S, Hirsch D, Killian JK, Gaedcke J, Jo P, Ponsa I, Miró R, Rüschoff J, Seitz G, et al. Molecular patterns in the evolution of serrated lesion of the colorectum. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1800–1810. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nosho K, Igarashi H, Nojima M, Ito M, Maruyama R, Yoshii S, Naito T, Sukawa Y, Mikami M, Sumioka W, et al. Association of microRNA-31 with BRAF mutation, colorectal cancer survival and serrated pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:776–783. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patai AV, Molnár B, Tulassay Z, Sipos F. Serrated pathway: alternative route to colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:607–615. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i5.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rustagi T, Rangasamy P, Myers M, Sanders M, Vaziri H, Wu GY, Birk JW, Protiva P, Anderson JC. Sessile serrated adenomas in the proximal colon are likely to be flat, large and occur in smokers. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5271–5277. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i32.5271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosman FT, World Health Organization. International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2088–2100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, Brown I, Leggett B, Whitehall V. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013;62:367–386. doi: 10.1111/his.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein NS. Small colonic microsatellite unstable adenocarcinomas and high-grade epithelial dysplasias in sessile serrated adenoma polypectomy specimens: a study of eight cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:132–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosty C, Hewett DG, Brown IS, Leggett BA, Whitehall VL. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: current understanding of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:287–302. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conesa-Zamora P, García-Solano J, García-García F, Turpin Mdel C, Trujillo-Santos J, Torres-Moreno D, Oviedo-Ramírez I, Carbonell-Muñoz R, Muñoz-Delgado E, Rodriguez-Braun E, et al. Expression profiling shows differential molecular pathways and provides potential new diagnostic biomarkers for colorectal serrated adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:297–307. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitehall VL, Rickman C, Bond CE, Ramsnes I, Greco SA, Umapathy A, McKeone D, Faleiro RJ, Buttenshaw RL, Worthley DL, et al. Oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancers and polyps. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:813–820. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jass JR, Baker K, Zlobec I, Higuchi T, Barker M, Buchanan D, Young J. Advanced colorectal polyps with the molecular and morphological features of serrated polyps and adenomas: concept of a ‘fusion’ pathway to colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2006;49:121–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaneda A, Wang CJ, Cheong R, Timp W, Onyango P, Wen B, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Ohlsson R, Andraos R, Pearson MA, et al. Enhanced sensitivity to IGF-II signaling links loss of imprinting of IGF2 to increased cell proliferation and tumor risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20926–20931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710359105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakatani T, Kaneda A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Carter MG, de Boom Witzel S, Okano H, Ko MS, Ohlsson R, Longo DL, Feinberg AP. Loss of imprinting of Igf2 alters intestinal maturation and tumorigenesis in mice. Science. 2005;307:1976–1978. doi: 10.1126/science.1108080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell AC, Felsenfeld G. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 2000;405:482–485. doi: 10.1038/35013100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hark AT, Schoenherr CJ, Katz DJ, Ingram RS, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM. CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature. 2000;405:486–489. doi: 10.1038/35013106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui H, Onyango P, Brandenburg S, Wu Y, Hsieh CL, Feinberg AP. Loss of imprinting in colorectal cancer linked to hypomethylation of H19 and IGF2. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6442–6446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibrahim AE, Arends MJ, Silva AL, Wyllie AH, Greger L, Ito Y, Vowler SL, Huang TH, Tavaré S, Murrell A, et al. Sequential DNA methylation changes are associated with DNMT3B overexpression in colorectal neoplastic progression. Gut. 2011;60:499–508. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baba Y, Nosho K, Shima K, Huttenhower C, Tanaka N, Hazra A, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Hypomethylation of the IGF2 DMR in colorectal tumors, detected by bisulfite pyrosequencing, is associated with poor prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1855–1864. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao X, Morikawa T, Lochhead P, Imamura Y, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Nosho K, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Prognostic role of PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer: cohort study and literature review. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2257–2268. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sukawa Y, Yamamoto H, Nosho K, Kunimoto H, Suzuki H, Adachi Y, Nakazawa M, Nobuoka T, Kawayama M, Mikami M, et al. Alterations in the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-v-Akt pathway in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6577–6586. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Igarashi S, Suzuki H, Niinuma T, Shimizu H, Nojima M, Iwaki H, Nobuoka T, Nishida T, Miyazaki Y, Takamaru H, et al. A novel correlation between LINE-1 hypomethylation and the malignancy of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5114–5123. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwagami S, Baba Y, Watanabe M, Shigaki H, Miyake K, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Sakamaki K, Ohashi Y, Baba H. LINE-1 hypomethylation is associated with a poor prognosis among patients with curatively resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2013;257:449–455. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826d8602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC, Torlakovic G, Nesland JM. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:65–81. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, Kawasaki T, Chan AT, Schernhammer ES, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS. A cohort study of tumoral LINE-1 hypomethylation and prognosis in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1734–1738. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baba Y, Huttenhower C, Nosho K, Tanaka N, Shima K, Hazra A, Schernhammer ES, Hunter DJ, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, et al. Epigenomic diversity of colorectal cancer indicated by LINE-1 methylation in a database of 869 tumors. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:125. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antelo M, Balaguer F, Shia J, Shen Y, Hur K, Moreira L, Cuatrecasas M, Bujanda L, Giraldez MD, Takahashi M, et al. A high degree of LINE-1 hypomethylation is a unique feature of early-onset colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hur K, Cejas P, Feliu J, Moreno-Rubio J, Burgos E, Boland CR, Goel A. Hypomethylation of long interspersed nuclear element-1 (LINE-1) leads to activation of proto-oncogenes in human colorectal cancer metastasis. Gut. 2014;63:635–646. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benard A, van de Velde CJ, Lessard L, Putter H, Takeshima L, Kuppen PJ, Hoon DS. Epigenetic status of LINE-1 predicts clinical outcome in early-stage rectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:3073–3083. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murata A, Baba Y, Watanabe M, Shigaki H, Miyake K, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Iwagami S, Sakamoto Y, Miyamoto Y, et al. Methylation levels of LINE-1 in primary lesion and matched metastatic lesions of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:408–415. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogino S, Nishihara R, Lochhead P, Imamura Y, Kuchiba A, Morikawa T, Yamauchi M, Liao X, Qian ZR, Sun R, et al. Prospective study of family history and colorectal cancer risk by tumor LINE-1 methylation level. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:130–140. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cunningham JM, Christensen ER, Tester DJ, Kim CY, Roche PC, Burgart LJ, Thibodeau SN. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter in colon cancer with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3455–3460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheridan TB, Fenton H, Lewin MR, Burkart AL, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Frankel WL, Montgomery E. Sessile serrated adenomas with low- and high-grade dysplasia and early carcinomas: an immunohistochemical study of serrated lesions “caught in the act”. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126:564–571. doi: 10.1309/C7JE8BVL8420V5VT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang S, Farraye FA, Mack C, Posnik O, O’Brien MJ. BRAF and KRAS Mutations in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colorectum: relationship to histology and CpG island methylation status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1452–1459. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000141404.56839.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han Y, Zhou ZY. Clinical features and molecular alterations of traditional serrated adenoma in sporadic colorectal carcinogenesis. J Dig Dis. 2011;12:193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]