Abstract

AIM: To assess the clinical significance of pouch size in total gastrectomy for gastric malignancies.

METHODS: We manually searched the English-language literature in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and BIOSIS Previews up to October 31, 2013. Only randomized control trials comparing small pouch with large pouch in gastric reconstruction after total gastrectomy were eligible for inclusion. Two reviewers independently carried out the literature search, study selection, data extraction and quality assessment of included publications. Standard mean difference (SMD) or relative risk (RR) and corresponding 95%CI were calculated as summary measures of effects.

RESULTS: Five RCTs published between 1996 and 2011 comparing small pouch formation with large pouch formation after total gastrectomy were included. Eating capacity per meal in patients with a small pouch was significantly higher than that in patients with a large pouch (SMD = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.25-1.44, I2 = 0, P = 0.792), and the operative time spent in the small pouch group was significantly longer than that in the large pouch group [SMD = -3.87, 95%CI: -7.68-(-0.09), I2 = 95.6%, P = 0]. There were no significant differences in body weight at 3 mo (SMD = 1.45, 95%CI: -4.24-7.15, I2 = 97.7%, P = 0) or 12 mo (SMD = -1.34, 95%CI: -3.67-0.99, I2 = 94.2%, P = 0) after gastrectomy, and no significant improvement of post-gastrectomy symptoms (heartburn, RR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.12-1.29, I2 = 0, P = 0.386; dysphagia, RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.58-1.27, I2 = 0, P = 0.435; and vomiting, RR = 0.5, 95%CI: 0.15-1.62, I2 = 0, P = 0.981) between the two groups.

CONCLUSION: Small pouch can significantly improve the eating capacity per meal after surgery, and may improve the post-gastrectomy symptoms, including heartburn, dysphagia and vomiting.

Keywords: Total gastrectomy, Gastric cancer, Pouch size, Systematic review

Core tip: Choosing the optimal pouch reconstruction in total gastrectomy is still a controversial area of clinical research, mainly due to the lack of information about the standardization of pouch design. This is the first meta-analysis about standardization of pouch reconstruction design after total gastrectomy, which suggests that the pouch size may be an important factor influencing the clinical outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Since the first successful total gastrectomy was described in 1897[1], more than 60 types of digestive tract reconstruction have been proposed[2]. However, the selection of an appropriate reconstructive technique in total gastrectomy is still a controversial area of clinical research[3].

One of the most frequent debates about this topic is the formation of an appropriate replacement gastric reservoir[4]. A recent meta-analysis has shown that the formation of a pouch reservoir has significant clinical advantages[5]. However, it is hard to choose the optimal pouch reconstruction because there is little information about standardization of pouch design. In particular, the choice of a small or large pouch seems to be driven by surgeons’ personal decisions without any established rules. Pouch formation aims to provide a reservoir, therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the size of the pouch may affect the patients’ outcome. Although it is a major question that surgeons have to address when they perform pouch formation after total gastrectomy, only a few studies with a small number of patients have been conducted with regard to pouch size after total gastrectomy with curative intent[6-11]. Furthermore, some of these studies have shown inconsistent conclusions[12,13].

To address this issue, we reviewed the published literature and aimed to assess the clinical value of pouch size after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. We believe that such research will contribute to an objective evaluation of the importance of pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Only randomized control trials (RCTs) were included in our analysis. The studies had to address whether the size of the pouch reservoir after total gastrectomy influenced clinical outcome. Different reconstructive techniques may have an impact on clinical outcome, thus, all articles must compare small pouches with large pouches with the same pouch shape. Studies that focused only on the effect of the gastric reservoir or preservation of duodenal transit were excluded.

Data sources and search strategy

The English-language literature was manually and independently searched by two reviewers in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and BIOSIS Previews up to October 31, 2013. Three groups of keywords were used in the search strategy: (1) gastric cancer, gastric malignancy, gastric neoplasm, gastric carcinoma, stomach cancer, stomach malignancy, stomach neoplasm, stomach carcinoma; (2) gastric resection, total gastrectomy, reconstruction; and (3) pouch, reservoir, length, size.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (Dong HL and Ding XW), working independently and in parallel, reviewed abstracts and assessed the full texts to examine eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with the third researcher (Huang YB). The following data were extracted independently from each of the included publications: authors, study period, study design, number of patients, length of follow-up, main results, and outcome. When key information was deficient or not available in the publication, we tried to obtain the data by contacting the authors through email or telephone.

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers according to Cochrane Handbook 5.1.0 (Chapter 8)[14] based on six perspectives: sequence generation, allocate concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other source of bias. To reduce the bias of the judgment, the included studies were independently assessed by two reviewers and any controversial issues were discussed with a third researcher.

Statistical analysis

This systematic review was conducted according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration and the Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analysis guidelines[15,16]. Standard mean difference (SMD) or relative risk (RR) and corresponding 95%CI were calculated as summary measures of effects for continuous outcomes (e.g., operative time, eating capacity per meal, and body weight) and binary outcomes (e.g., heartburn, dysphagia, and vomiting). Fixed-effect or random-effect model was chosen according to the level of heterogeneity, which was assessed using the I2 statistic. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using STATA version 12.0.

RESULTS

A total of 29 studies were initially identified on pouch formation after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. We excluded 18 RCTs that compared the effect but not the size of the pouch[17-34]. Six papers[8,12,13,35-37] were excluded because of duplicated publication or not providing essential information. Thus, we included the remaining five trials[6,7,9-11] published between 1996 and 2011, including 118 patients after total gastrectomy, that compared small pouch with large pouch. Schwarz et al[11] conducted two comparisons between three gastrectomy methods (RY vs RY Pouch vs JI Pouch), so this study was regarded as two trials. Two papers conducted by Tanaka et al[9,10] came from the same study, but they had reported different clinical outcomes, therefore both of them were included in the final analysis. The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1, and the main results are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Reconstruction | Study period | Group | Pouch size (cm) | Cases | Age (yr) | Gender (M/F) | Tumor stage | Follow-up (yr) |

| Tsujimoto et al[6] | Double-tract | 2002-2007 | Small pouch | 9.2 ± 1.1 | 13 | 54.6 ± 10.0 | 7/6 | IA IB II IIIA | 5.0 |

| Large pouch | 12.5 ± 1.5 | 14 | 61.7 ± 8.2 | 12/2 | 4 3 3 3 | ||||

| 6 1 3 4 | |||||||||

| Hoksch et al[8] | Pouch-JI | 1995-1999 | Small pouch | 7 | 15 | 52 (25-72) | 6/9 | 0 IA IB II IIIA IIIB IV | 1.0 |

| Large pouch | 15 | 13 | 61 (51-74) | 6/7 | 0 2 2 8 2 1 0 | ||||

| 1 2 5 3 1 1 0 | |||||||||

| Tanaka et al[9] | Double-tract | 1992-1995 | Small pouch | 15 | 12 | 57.2 ± 11.09 | 7/5 | I II III IV | 1.0 |

| Large pouch | 20 | 9 | 62.1 ± 9.44 | 6/3 | 4 3 5 0 | ||||

| 4 1 4 0 | |||||||||

| Tanaka et al[10] | Double-tract | 1992-1994 | Small pouch | 15 | 9 | 56.4 ± 15 | 3/6 | I II III IV | 1.0 |

| Large pouch | 20 | 9 | 62.1 ± 9.44 | 6/3 | 2 3 4 0 | ||||

| 4 1 4 0 | |||||||||

| Schwarz et al[11] | Pouch-JI | 1990-1993 | Small pouch | 10 | 12 | 59 ± 3.1 | 9/3 | I + II III + IV | 0.5 |

| Large pouch | 20 | 12 | 62 ± 3.59 | 4/8 | 6 6 | ||||

| 8 4 | |||||||||

| Schwarz et al[11] | Pouch-RY | 1990-1993 | Small pouch | 10 | 12 | 63 ± 3.47 | 9/3 | I + II III + IV | 0.5 |

| Large pouch | 20 | 12 | 65 ± 3.74 | 4/8 | 5 7 | ||||

| 4 8 |

JI: Jejunal interposition reconstruction; RY: Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

Table 2.

Main results of included studies

| Study | Group | Cases | Morbidity | Mortality | OP time (min) | Heartburn incidence | Dysphagia | Vomiting | Daily meals (n) | Eating capacity per meal | Body weight | Quality of life | |||||||||||

| Tsujimoto et al[6] | Small pouch | 13 | 2/13 | 0 | 331.8 ± 34.4 | 1 yr | 2 yr | 1 yr | 2 yr | 1 yr | 2 yr | 1 yr | 2 yr | 1 yr | 2 yr | NR | |||||||

| 2/11 | 0 | 7/11 | 0 | 1/11 | 0 | 3 time | 4 time | 5 time | 3 time | 4 time | |||||||||||||

| Large pouch | 14 | 2/14 | 0 | 343.8 ± 36.7 | 4/13 | 0 | 8/13 | 1/13 | 3/13 | 1/13 | 10/11 | 9/13 | 0 | 10/11 | 1/11 | 69.1% ± 19.7% | 78.6% ± 6.9% | 88.4% ± 7.4% | 90.2% ± 6.4% | NR | |||

| 9/13 | 3/13 | 1/13 | 8/13 | 5/13 | 52.3% ± 16.9% | 61.4% ± 23.4% | 85.9% ± 4.3% | 80.9% ± 7.1% | |||||||||||||||

| Hoksch et al[8] | Small pouch | 15 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Pre | 14 d | 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 yr | NR | 14 d | 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 yr | EORTC QLQ-C30 | ||||

| Large pouch | 13 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | NR | 95% ± 0.6% | 90% ± 1.0% | 87% ± 0.8% | 87% ± 1.2% | ||||||

| 4.5 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 95% ± 0.4% | 86% ± 0.8% | 86% ± 0.8% | 92% ± 1.1% | |||||||||||||||

| Tanaka et al[9] | Small pouch | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3 mo | 1 yr | 3 mo | 1 yr | NR | |||||||||

| Large pouch | 9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 55.2% ± 25% | 59.1% ± 8.6% | 57.05% ± 4.73% | 85.5% ± 4.2% | NR | ||||||||||

| 40.6% ± 9% | 49.6% ± 16.5% | 67.73% ± 10.11% | 87.3% ± 6.9% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanaka et al[10] | Small pouch | 9 | NR | NR | NR | 1 yr | 1 yr | 1 yr | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||||

| 1/9 | 6/9 | 2/9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Large pouch | 9 | NR | NR | NR | 5/9 | 8/9 | 4/9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||||||||

| Schwarz et al[11] | Small pouch | 12 | NR | NR | 335 ± 9.79 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Absolute weights | UC | |||||||||||

| Large pouch | 12 | NR | NR | 374 ± 11.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||||||||||

| Schwarz et al[11] | Small pouch | 12 | NR | NR | 295 ± 7.51 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Absolute weights | UC | |||||||||||

| Large pouch | 12 | NR | NR | 360 ± 8.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||||||||||

NR: Not reported; UC: Unclear.

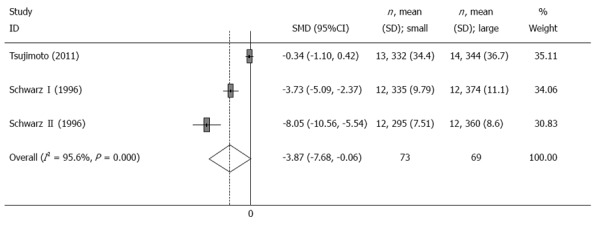

Operative time

Operative time was provided in three trials[6,11]. The mean operative time spent in the small pouch group was significantly longer than that in the large pouch group [SMD = -3.87, 95%CI: -7.68-(-0.09), I2 = 95.6%, P = 0] (Table 2, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of the operative time. Note: Weights are from random effects analysis.

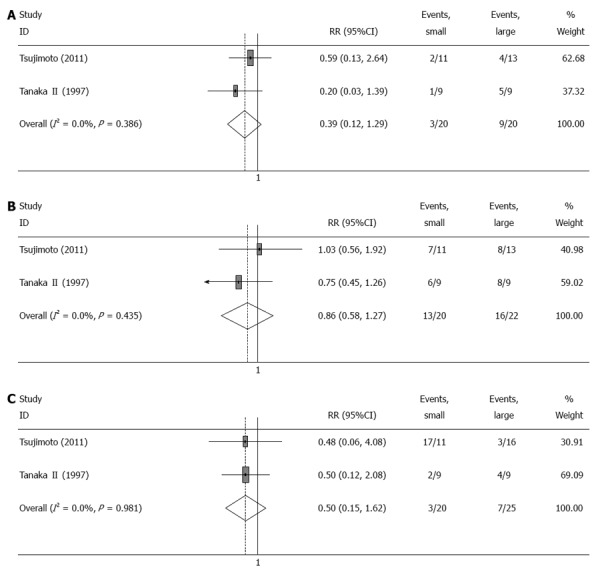

Post-gastrectomy symptoms

The post-gastrectomy symptoms were evaluated in four trials[6,9-11]. Two trials reported the incidence rates of heartburn, dysphagia and vomiting 1 year after surgery[6,10]. Compared with large pouch, there was no significant improvement in post-gastrectomy symptoms (heartburn, RR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.12-1.29, I2 = 0, P = 0.386; dysphagia, RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.58-1.27, I2 = 0, P = 0.435; and vomiting, RR = 0.5, 95%CI: 0.15-1.62, I2 = 0, P = 0.981) associated with small pouch (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of post-gastrectomy symptoms 12 mo after surgery. A: Heartbum; B: Dysphagia; C: Vomiting. Note: Weights are from random effects analysis.

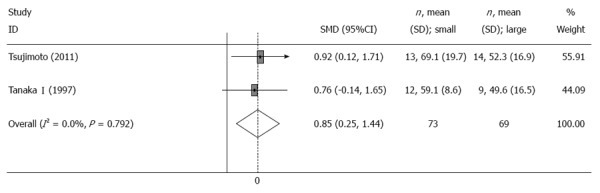

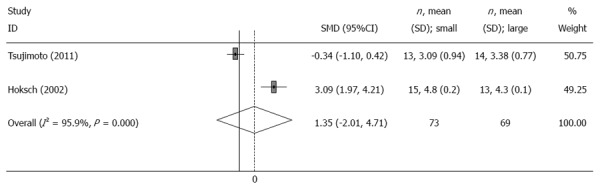

Food intake

Two trials[6,9] reported the change of mean eating capacity per meal before and after the operation. The meta-analysis showed that eating capacity per meal in patients with a small pouch was significantly larger than that in patients with a large pouch (SMD = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.25-1.44, I2 = 0, P = 0.792) (Table 2, Figure 3). Furthermore, the other two trials reported the frequency of daily meals[6,7], and results from the meta-analysis showed no significant differences between the two groups (SMD = 1.35, 95%CI: -2.01-4.71, I2 = 95.9%, P = 0) (Table 2, Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of eating capability per meal 12 mo after surgery. Note: Weights are from random effects analysis.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of frequency of daily meals 12 mo after surgery. Note: Weights are from random effects analysis.

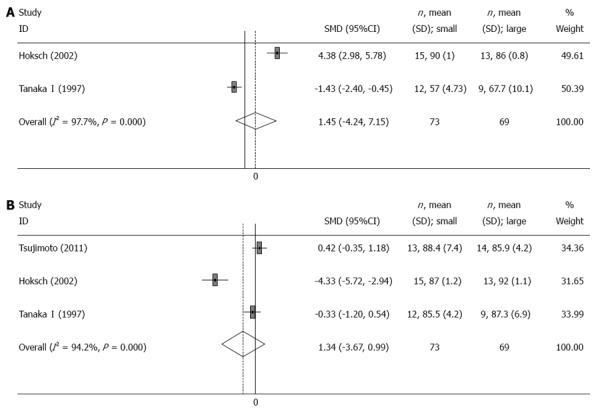

Body weight

Two[7,9] and three[6,7,9] trials reported the mean change of body weight 3 and 12 mo after the operation, respectively. There was no significant difference in body weight between the small pouch group and the large pouch group at 3 mo (SMD = 1.45, 95%CI: -4.24-7.15, I2 = 97.7%, P = 0) or 12 mo (SMD = -1.34, 95%CI: -3.67-0.99, I2 = 94.2%, P = 0) after surgery (Table 2, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of change of body weight after surgery. A: 3 mo; B: 12 mo. Note: Weights are from random effects analysis.

DISCUSSION

The selection of optimal reconstructive method is one of the main considerations after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. By recreating the reservoir function of the stomach, pouch reconstruction has been used by many surgeons in order to improve the patient’s eating capacity and quality of life (QOL). Although the first pouch reconstruction was described as early as in 1922[38], it still remains hard to choose the optimal method because there has been little attempt at the standardization of pouch design.

Recently, pouch size has arisen as one of the most important issues when the surgeon considers pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy[39]. Nanthakumaran et al[13] have constructed a mathematical model to quantify gastric pouch volume and justify a range of gastric pouch dimensions to be tested in an in vitro model. Based on their model, they demonstrated that smaller pouches never achieve adequate volumes at basal pressures, and they have proposed that further in vivo studies should be based upon large pouch designs. Some studies have confirmed this view[12]. However, other studies have shown the contrary conclusion[6,10]. Some studies have not found any difference in postoperative outcomes between small and large pouches, suggesting that the size of pouch does not influence QOL[7,11].

In this meta-analysis, we found that patients with a small pouch showed significantly greater eating capacity per meal compared with those with a large pouch. This may have been due to the small pouch having better and faster emptying, which causes fewer abnormalities of the gastrointestinal nervous system[12]. Patients with a small pouch after total gastrectomy may have a better appetite, which can help to improve QOL.

With respect to perioperative course, we found that small pouches prolonged operative time compared with large pouches. However, pouch creation was mainly performed using a stapler device, and does not need much time. Operative time also includes the time spent on tumor resection, lymph node dissection, and reconstruction of the digestive tract. Therefore, we estimate that the main reason for the significant differences in the operative time between the two groups may have been related to the surgeons’ experience.

For post-gastrectomy symptoms, no significant differences were found in the incidence of heartburn, dysphagia or vomiting between the small pouch and large pouch groups. Large pouches may cause delayed gastric emptying, which is related to higher frequencies of post-gastrectomy symptoms. However, only two trials reported such data, which only presented a slight tendency towards lower frequencies of post-gastrectomy symptoms in small pouch patients.

For the body weight, no significant differences were found between the two groups. One reason is that an inadequate number of trials may not provide significant results. Another reason is that the follow-up period was short (12 mo), thus, the body weight of patients with a pouch may have changed little during such a short period.

Several features, such as mortality, morbidity and QOL, were hard to analyze because such results were measured by different methods or even not mentioned at all in these trials.

Our meta-analysis had several possible limitations. First, the total number of analyzed patients was too small, which may have resulted in a failure to identify significant differences. This also reflects that pouch size is a neglected topic in pouch formation. Second, the methodological quality of the available articles was not satisfactory because of insufficient information and small numbers of patients, therefore, we used the random-effects model for the meta-analysis. Third, the follow-up period was not long enough to show significant differences. All the data were analyzed within 12 mo. Fourth, pouch size varied from 7 to 20 cm, which made it almost impossible to assume the optimal size of pouch, and was only good for comparing small and large pouches.

Finally, we want to emphasize that we found that patients with a small pouch showed improved eating capacity per meal, which may be in accordance with the results of a meta-analysis published in 2009[5], which reported that patients with a pouch had some significant clinical advantages, including less dumping incidence and heartburn incidence, better food intake, and improved QOL. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that small pouches can significantly improve the eating capacity per meal after surgery, and seem to improve the post-gastrectomy symptoms, including heartburn, dysphagia and vomiting.

Although more research is required to confirm our results, our meta-analysis at least suggested that pouch size may be an important factor influencing the clinical outcome of pouch construction after total gastrectomy. We suggest that surgeons need to pay more attention to pouch size when they perform pouch formation after total gastrectomy.

COMMENTS

Background

The selection of optimal reconstructive method is one of the main areas involved in reconstruction after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Although the first pouch reconstruction was described as early as in 1922, it is still hard to choose the optimal pouch reconstruction because there has been little attempt at standardization of pouch design. In particular, the clinical significance of pouch size in total gastrectomy for gastric malignancies is currently unclear.

Research frontiers

Recently, pouch size has arisen as one of the most important issues when the surgeon considers pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy. Moreover, several studies have investigated this topic, although some of these have shown inconsistent conclusions.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The present study is the first meta-analysis about standardization of pouch design after total gastrectomy, and the authors showed that small pouches can significantly improve the eating capacity per meal after surgery, and seem to improve the post-gastrectomy symptoms, including heartburn, dysphagia and vomiting.

Applications

This study furthers the understanding of the influence of pouch size on the clinical outcome of pouch construction after total gastrectomy. The authors suggest that surgeons need to pay more attention to pouch size when they perform pouch formation after total gastrectomy, and more research should focus on this topic in the future.

Peer review

This is a well-written paper that will add a great deal to the literature on the subject. The authors’ findings will arouse more attention to pouch size, and future research is needed.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Luyer MDP, Teoh AYB, Tovey FI S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Schlatter C. Über Ernährung und Verdauung nach vollständiger Entfernung des Magens, Oesophagoenterostomie, beim Menschen. Beitr Klin Chir. 1897;19:589–594. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin AC, Espat NJ. Total gastrectomy: options for the restoration of gastrointestinal continuity. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:271–276. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piessen G, Triboulet JP, Mariette C. Reconstruction after gastrectomy: which technique is best? J Visc Surg. 2010;147:e273–e283. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibata C, Ueno T, Kakyou M, Kinouchi M, Sasaki I. Results of reconstruction with jejunal pouch after gastrectomy: correlation with gastrointestinal motor activity. Dig Surg. 2009;26:177–186. doi: 10.1159/000217798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gertler R, Rosenberg R, Feith M, Schuster T, Friess H. Pouch vs. no pouch following total gastrectomy: meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2838–2851. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsujimoto H, Sakamoto N, Ichikura T, Hiraki S, Yaguchi Y, Kumano I, Matsumoto Y, Yoshida K, Ono S, Yamamoto J, et al. Optimal size of jejunal pouch as a reservoir after total gastrectomy: a single-center prospective randomized study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1777–1782. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoksch B, Ablassmaier B, Zieren J, Müller JM. Quality of life after gastrectomy: Longmire’s reconstruction alone compared with additional pouch reconstruction. World J Surg. 2002;26:335–341. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoksch B, Müller JM. [Complication rate after gastrectomy and pouch reconstruction with Longmire interposition] Zentralbl Chir. 2000;125:875–879. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka T, Kusunoki M, Fujiwara Y, Nakagawa K, Utsunomiya J. Jejunal pouch length influences metabolism after total gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:891–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka T, Fujiwara Y, Nakagawa K, Kusunoki M, Utunomiya J. Reflux esophagitis after total gastrectomy with jejunal pouch reconstruction: comparison of long and short pouches. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:821–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarz A, Büchler M, Usinger K, Rieger H, Glasbrenner B, Friess H, Kunz R, Beger HG. Importance of the duodenal passage and pouch volume after total gastrectomy and reconstruction with the Ulm pouch: prospective randomized clinical study. World J Surg. 1996;20:60–66; discussion 66-67. doi: 10.1007/s002689900011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tono C, Terashima M, Takagane A, Abe K. Ideal reconstruction after total gastrectomy by the interposition of a jejunal pouch considered by emptying time. World J Surg. 2003;27:1113–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanthakumaran S, Suttie SA, Chandler HW, Park KG. Optimal gastric pouch reconstruction post-gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2008;11:33–36. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke M, Horton R. Bringing it all together: Lancet-Cochrane collaborate on systematic reviews. Lancet. 2001;357:1728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horváth OP, Kalmár K, Cseke L. Aboral pouch with preserved duodenal passage--new reconstruction method after total gastrectomy. Dig Surg. 2002;19:261–264; discussion 264-266. doi: 10.1159/000064575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei HB, Wei B, Zheng ZH, Zheng F, Qiu WS, Guo WP, Wang TB, Xu J, Chen TF. Comparative study on three types of alimentary reconstruction after total gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1376–1382. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozzetti F, Bonfanti G, Castellani R, Maffioli L, Rubino A, Diazzi G, Cozzaglio L, Gennari L. Comparing reconstruction with Roux-en-Y to a pouch following total gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalmár K, Cseke L, Zámbó K, Horváth OP. Comparison of quality of life and nutritional parameters after total gastrectomy and a new type of pouch construction with simple Roux-en-Y reconstruction: preliminary results of a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1791–1796. doi: 10.1023/a:1010634427766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iivonen MK, Koskinen MO, Ikonen TJ, Matikainen MJ. Emptying of the jejunal pouch and Roux-en-Y limb after total gastrectomy--a randomised, prospective study. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:742–747. doi: 10.1080/11024159950189500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liedman B, Andersson H, Berglund B, Bosaeus I, Hugosson I, Olbe L, Lundell L. Food intake after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma: the role of a gastric reservoir. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1138–1143. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz A, Schoenberg MH, Beger HG. [Pouch stomach reconstruction after gastrectomy] Z Gastroenterol. 1999;37:287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kono K, Iizuka H, Sekikawa T, Sugai H, Takahashi A, Fujii H, Matsumoto Y. Improved quality of life with jejunal pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 2003;185:150–154. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakane Y, Okumura S, Akehira K, Okamura S, Boku T, Okusa T, Tanaka K, Hioki K. Jejunal pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy for cancer. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 1995;222:27–35. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fein M, Fuchs KH, Thalheimer A, Freys SM, Heimbucher J, Thiede A. Long-term benefits of Roux-en-Y pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2008;247:759–765. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318167748c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iivonen MK, Mattila JJ, Nordback IH, Matikainen MJ. Long-term follow-up of patients with jejunal pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy. A randomized prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:679–685. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paimela H, Ketola S, Iivonen M, Tomminen T, Könönen E, Oksala N, Mustonen H. Long-term results after surgery for gastric cancer with or without jejunal reservoir: results of surgery for gastric cancer in Kanta-Häme central hospital in two consecutive periods without or with jejunal pouch reconstruction in 1985-1998. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;36:147–153. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:36:3:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horváth OP K, Cseke L, Pótó L, Zámbó K. Nutritional and life-quality consequences of aboral pouch construction after total gastrectomy: a randomized, controlled study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:558–563. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Troidl H, Kusche J, Vestweber KH, Eypasch E, Maul U. Pouch versus esophagojejunostomy after total gastrectomy: a randomized clinical trial. World J Surg. 1987;11:699–712. doi: 10.1007/BF01656592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirao M, Kurokawa Y, Fujitani K, Tsujinaka T. Randomized controlled trial of Roux-en-Y versus rho-shaped-Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2009;33:290–295. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs KH, Thiede A, Engemann R, Deltz E, Stremme O, Hamelmann H. Reconstruction of the food passage after total gastrectomy: randomized trial. World J Surg. 1995;19:698–705; discussion 705-706. doi: 10.1007/BF00295908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adachi S, Inagawa S, Enomoto T, Shinozaki E, Oda T, Kawamoto T. Subjective and functional results after total gastrectomy: prospective study for longterm comparison of reconstruction procedures. Gastric Cancer. 2003;6:24–29. doi: 10.1007/s101200300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nozoe T, Anai H, Sugimachi K. Usefulness of reconstruction with jejunal pouch in total gastrectomy for gastric cancer in early improvement of nutritional condition. Am J Surg. 2001;181:274–278. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakane Y, Akehira K, Okumura S, Okamura S, Boku T, Okusa T, Hioki K. Jejunal pouch and interposition reconstruction after total gastrectomy for cancer. Surg Today. 1997;27:696–701. doi: 10.1007/BF02384979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Citone G, Paoluzzi P, Massa R, Perri S, Di Nardo A, Catani M, Pietroiusti A, Longo G. [Prevention of alkaline esophagitis after total gastrectomy and Longmire-Mouchet reconstruction: ideal length of the interposed jejunal loop] Minerva Chir. 1988;43:481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kieninger G, Koslowski L, Kummer D. [Stomach replacement by iso-anisoperistaltic jejunum interposition (Tübinger replacement stomach)] Chirurg. 1981;52:505–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunt CJ. Construction of food pouch from segment of jejunum as substitute for stomach in total gastrectomy. AMA Arch Surg. 1952;64:601–608. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1952.01260010619009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumagai K, Shimizu K, Yokoyama N, Aida S, Arima S, Aikou T. Questionnaire survey regarding the current status and controversial issues concerning reconstruction after gastrectomy in Japan. Surg Today. 2012;42:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0159-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]