Abstract

The postnatal feeding practices of obese and overweight mothers may place their children at particular risk for the development of obesity through shared biology and family environments. This paper reviews the feeding practices of obese mothers, describes potential mechanisms linking maternal feeding behaviors to child obesity risk, and highlights potential avenues for intervention. This review documents that supporting breastfeeding, improving the food choices of obese women, and encouraging the development of feeding styles that are responsive to hunger and satiety cues are important for improving the quality of the eating environment and preventing the intergenerational transmission of obesity.

With the growing prevalence of obesity worldwide, an increasing proportion of women enter pregnancy overweight or obese. In the United States, 35% of women over the age of 20 are obese (BMI>30 kg/m2) and 64% are overweight or obese (BMI>25 kg/m2;).1 Although the national prevalence of obesity in pregnant women is not available, data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a population-based surveillance system in 26 US states and New York City, indicate that one in five women giving birth was obese in 2004-2005.2 The potential public health problem of maternal obesity and overweight extends from immediate consequences of poor birth outcomes, such as stillbirth, macrosomia, and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, to longer-term consequences for offspring obesity and chronic disease.3-5 Maternal obesity prior to, during, and after pregnancy increases pediatric obesity risk.3,6,7 Maternal obesity in early pregnancy more than doubles the risk of overweight in young children,8 and maternal adiposity, measured through mid-upper arm circumference, is associated with higher fat mass in early childhood.6,9 Indeed, a family history of obesity, and maternal obesity in particular, is one of the strongest risk factors for obesity at any stage in the lifecycle.10

This concordance between maternal and child obesity stems from a number of factors, including shared genetic risk factors,11 nutritional conditions of the intra-uterine environment,3,4,7 and shared postnatal dietary, physical, and behavioral characteristics.12-14 While the relative importance of each of these roles continues to be debated,3,7,12 the impact of maternal obesity on child feeding, a modifiable postnatal risk factor moderating child obesity risk,15 may be particularly important in shaping long-term diet by influencing food availability, modeling eating behaviors, and shaping food preferences. Feeding differences between obese and non-obese mothers have generally received less attention in the literature; however, obese mothers are less likely to breastfeed16,17 and more likely to feed their children too much or provide a poor quality diet.18 Since young children learn how, what, when and how much to eat based on familial, and particularly maternal, beliefs, attitudes, and practices surrounding food and eating during the transition to solid foods and family diets,19,20 children of obese mothers may be at greater risk for the development of obesogenic, lifelong eating practices. Thus, this paper reviews overweight and obese mothers' infant and toddler feeding practices, focusing on the first two years of life where possible, discusses proposed mechanisms linking early feeding practices to the intergenerational transmission of obesity in humans and animal models, and highlights potential opportunities for intervention.

Maternal Obesity and Breastfeeding

One aspect of early feeding differences between obese and non-obese mothers that has received a great deal of attention is breastfeeding initiation and duration. Breastfeeding initiation is consistently lower and duration consistently shorter in overweight and obese women compared to normal-weight women. A recent meta-analysis found that overweight and obese women were 1.19-3.09 times less likely to initiate breastfeeding16 while a population-based study of nearly 300,000 births in the UK found that maternal obesity was associated with significantly reduced odds of breastfeeding at hospital discharge.21 Among overweight and obese women who do establish breastfeeding, duration is also shorter. Obese women are over 50% less likely to breastfeed at 6 months compared to normal weight women, even when adjusting for a number of potential confounders including breastfeeding intention, age, smoking, and depression.16

Weight-related disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration stem from a number of physiological and psychosocial causes. Obese mothers are more likely to experience complications during pregnancy and delivery, such as fetal macrosomia and caesarean-section delivery, leading to difficulty establishing breastfeeding.17 Excess adiposity prior to, during, and after pregnancy contributes to disregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis,22 low prolactin levels in response to infant suckling,23 and delayed onset of milk production.24 Overweight and obese women are nearly 2.5 times more likely than normal weight women to have a late arrival of milk,16 a significant risk factor for breastfeeding cessation or formula supplementation.25 Obese women also tend to have larger breasts, which can cause mechanical challenges for latching on and positioning during feeds and contribute to difficulties in establishing and maintaining breastfeeding.16 Additionally, infants of obese mothers may have a higher demand for energy intake and be less satisfied with breastmilk26 leading to perceived milk insufficiency.27 Obese mothers are also less likely to seek breastfeeding support when difficulties with milk production are encountered27 further reducing breastfeeding duration.

The role of physiology in limiting the breastfeeding capabilities of obese women remains unclear since the association between overweight/obesity and breastfeeding is confounded by a number of social and psychological factors. Obesity is more common among women who have lower socioeconomic status and depression, both independent risk factors for lower rates of breastfeeding.26,28 Adjustment for a host of potential confounders including race/ethnicity and poverty identified only a relatively small independent effect of maternal obesity on breastfeeding duration of less than 2 weeks.29 Moreover, the association between obesity and reduced breastfeeding does not appear to be universal across societies,16 suggesting that the social positioning of obese women and the stigma associated with maternal obesity are determinants of breastfeeding practice. A study of American women who were highly committed to breastfeeding and supported by their partners and physicians highlights the strong psychosocial influence on breastfeeding.30 Despite similar intentions to breastfeed, obese mothers breastfed for shorter durations and failed to meet their own breastfeeding goals, a finding that was explained in part by a lack of comfort and confidence in their bodies postpartum.30

Regardless of its causes, reduced breastfeeding may be an important mechanism in the intergenerational transmission of obesity. Although the importance of breastfeeding for preventing later obesity has recently been called in to question31, numerous studies indicate that breastfeeding provides weak to moderate protection against the development of later obesity, with an overall reduction in odds between 20 and 30%.32-34 Infants weaned earlier gain weight more rapidly35 possibly due to higher energy intakes from formula-feeding,36 impaired self-regulation,37 and earlier complementary feeding.38 The interaction between maternal weight status and breastfeeding practices on child obesity has less often been considered, but a study of Danish infants found that infants of overweight women had higher weight gains, shorter durations of breastfeeding, and earlier introduction to solid foods.35 The additive effect of maternal obesity and lack of breastfeeding on child overweight has been documented in 2636 American two to 14-year-old children, whose mothers participated in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79).39 Children with overweight mothers who did not breastfeed had a 6-fold greater risk for overweight compared to the breastfed children of normal-weight mothers.

Whether breastfeeding by obese mothers protects against child obesity remains an open question. In the NLSY79, breastfeeding for at least 4 months reduced the magnitude of risk of obesity --although obesity risk was still higher among the children of obese mothers-- indicating that breastfeeding remains protective even when mothers are obese.39 This finding contrasts research in humans and animal models documenting that maternal diet can alter the composition of breastmilk potentially attenuating its benefits.5 Obesity-derived alterations in fat metabolism negatively impact breastmilk triglyceride composition.40,41 Breastmilk contains a higher proportion of medium chain fatty acids when the fatty acids are produced via de novo synthesis in the breast than when they are derived from the maternal fat stores, which contribute longer-chain fatty acids (LCTA).41 Maternal obesity and/or high-fat diets then could reduce the proportion of the more readily digested medium chain fatty acids and increase the proportion of LCTA. Unlike medium chain fatty acids, LCTAs require bile for transport across the infant intestine and, in young infants with immature digestive systems, may not be well absorbed. Thus, milk with greater LCTAs could lead to greater infant hunger, a risk factor for formula and/or solid supplementation.

Along with these differences in fat content, differences in the hormonal content of obese mothers' breastmilk could play a critical role in programming the neural circuitry regulating appetite, energy balance and eating behavior in offspring.5,42,43 In rat models, the offspring of obese mothers fed a highly-palatable diet during pregnancy and lactation have higher levels of orexigenic peptides, develop hyperphagia, and have greater adiposity in adolescence and adulthood.5,7,43 While the exact mechanisms leading to hyperphagia have yet to be identified, elevated lipid, leptin or insulin levels in the plasma and breastmilk of obese mothers have been implicated as possible programming factors.5 Comparable studies are lacking in humans; however, measurement of infant sucking behavior indicates that exposure to maternal obesity induces changes in human infant eating behavior as well. Sucking frequency was 50% higher in 3-month-old infants born to obese mothers and predicted body weight at age 2.44 In addition to potential exposure to metabolic hormones in breastmilk, shared appetite traits between obese mothers and their offspring may also link maternal obesity to infant sucking behaviors. Recent research in a birth cohort of twins45 found that the appetite size of mothers and their 3-month-old infants were significantly correlated. Heritability modeling further suggested that shared genetics accounted for nearly 50% of the variance in appetite size. How breastfeeding may moderate these shared propensities to influence the development of appetitive characteristics merits further research.

Maternal Obesity and Child Diet Patterns

While the association between maternal obesity and reduced duration of breastfeeding is well-documented, few studies have examined differences in solid feeding practices between obese and normal-weight mothers.4,41,46 Yet this transition to solid foods is particularly important in the establishment of long-term eating behaviors. As children transition to the family diet, maternal diet preferences and practices exert greater influence on the types and amounts of foods available to young children which in turn shape child preferences and consumption. Mothers play an important role in modeling food choices14,47 and their weight status affects children's food preferences, perhaps even more than children's own weight status.48 Differences in the diets of obese mothers, who may more eat energy-dense, high-fat foods,49 therefore, could influence both what children are fed and the likelihood of early excess weight gain.

Few studies have directly examined the infant feeding practices of obese mothers, but much evidence documents that maternal food intake is associated with children's eating behaviors from a young age.50-53 Parent intake has been associated with child intake across all food groups except sugar-sweetened beverages,54 though the magnitude of this association differs across child age and weight status, sociodemographic indicators, and race/ethnicity.50,53 Poor maternal diet quality is associated with the early introduction and inappropriate quality of solid foods in infants55 and similarities in the types of foods consumed begin in the second year of life.53 In the limited research examining the infant feeding practices of obese mothers, obese mothers introduced solid foods sooner than normal-weight mothers35 and provided a poorer diet quality with higher proportions of “adult” foods to their infants.18

These solid feeding practices could contribute to higher energy intakes in infants and young children, a risk factor for later obesity.56 A small laboratory-based study found that infants born to obese mothers consumed more energy and more energy as carbohydrates than infants of normal-weight mothers and that these higher intakes were due to increased consumption of solid foods.46 More recently, 6-year-old children with obese mothers were found to consume more energy across 3-days of weighed food records.10 These higher intakes were seen despite a lack of difference in the energy density of selected foods, suggesting that greater intakes rather than diet choices per se were responsible for the higher calories consumed.

Along with modeling diet patterns, maternal food choices shape child food preferences. A heightened, shared preference for sweets and sugar-sweetened drinks has been identified in overweight and obese mothers and their children across a number of settings. Overweight mothers introduced sweets, pastries and sugar-sweetened beverages to infants earlier than normal weight mothers, and infants consumed these sweets more frequently if their mothers were overweight and ate sweets more frequently themselves.57 In a lab-based observational study, obese mothers and their preschool children ate more sweets than normal weight mothers and their children though there were no differences in consumption of other food types.58 Similarly, mothers and their children share preferences for high-fat foods. A number of studies have documented that parental preference for high-fat foods and parental adiposity are associated with preschool children's preferences for high fat foods49 and the percentage of energy consumed as fat.49,59 Such findings have led researchers to conclude that shared genetic predispositions to sweeter and higher-fat foods underlie the development of obesogenic diets in obese mothers and their children.14,60 Experimental animal models, however, also show that exposure to maternal high-sugar and high-fat diets during gestation or lactation increases offspring preference for higher sugar and fat diets into adulthood in rats, sheep and non-human primates.12,43 Rats whose mothers were fed high-fat “junk food” diets during pregnancy and lactation, for example, develop an exaggerated preference for fatty and/or sweet foods compared to control fed animals.42,61 Thus, both shared genetics and shared dietary exposures are likely important in determining long-term preferences.

Maternal Obesity and Child Feeding Behaviors

Along with these differences in diet patterns and intake, maternal feeding practices also shape the physical and emotional context of eating.20,62 Mothers' interactions with their children during meals, instrumental use of foods, and feeding styles influence children's energy balance and eating behavior, and evidence suggests these feeding practices differ between obese and normal-weight mothers. Obese mothers of infants and toddlers reported a lower degree of structure during feeding, higher television watching and lower interaction during meals, and a less set mealtime routine in a large, ethnically-diverse sample.63 Obese mothers also spent less time interacting with their infants and less time feeding them over the course of a 24-hour observation period in a lab-based study.46 Since the quality of family interactions during eating influences children's eating practices, attitudes towards food, and assessment of satiety,20 this lack of responsive interactions during feeding can negatively impact child intake.

Obese mothers may also model eating in response to factors external to hunger and satiety. A recent observational study64 found that mothers' responsiveness to fullness cues in their infants and toddlers was inversely associated with their own BMI. These findings suggest that overweight or obese mothers, who may be less aware of their own internal satiety cues, may similarly not recognize these cues in their infants. Obese mothers may consume foods for emotional reasons and, in their children, use foods instrumentally to reward or control child behavior.65 They may also encourage eating and prompt their children to eat more during meals.65 While relatively little research has focused on infants, studies show that preschool children with obese parents have higher responsiveness to foods60 and overeating in response to emotional cues than children with normal-weight parents.60,66 These findings are not universal, however, and a number of studies have found no difference between obese and normal-weight mothers in prompting child eating,65,67 using food as a reward or in response to emotional distress, or encouraging children to eat more.58,65,68,69 Disinhibited eating, an eating style characterized by the tendency to consume large amounts of palatable foods in a short time not in response to hunger,70 on the other hand, consistently differs between the children of obese and normal-weight mothers.70-73 Although eating in the absence of hunger (EAH), a behavioral measure of disinhibited eating, has not been studied in infants, preschool children show differences in EAH based on maternal obesity. Boys with obese mothers consumed more food in the absence of hunger –measured as snack consumption after an ad libitum meal consumed until full-- than normal weight boys.74 These results indicate that children with obese mothers may be more responsive food availability or, alternatively, less responsive to satiety cues.

Comparison of the feeding styles of obese and non-obese mothers also indicate that the emotional context and attitudes surrounding feeding differ by maternal weight status.65 Mothers with higher BMI reported using more restrictive feeding practices, limiting the quantity and quality of foods provided to their toddlers, and were observed using more pressure to get children to eat during mealtimes.68 Among mothers of 18-64 month-old children, mothers' BMI and concerns about her weight were related to the use of controlling (pressuring or restrictive) feeding practices.68 Similarly, mothers of preschool children reported a greater use of restriction when they had greater weight and eating concerns of their own,72 suggesting that restrictive practices are influenced by mothers' own struggles with their weight and concerns about their children's future weight struggles beginning early in life. However, other studies have found that higher maternal BMI73 and obesity65 were associated with lower levels of maternal control, so the relationship between maternal weight, weight concerns, and child feeding clearly varies across populations of mothers and children.

Interestingly, a number of studies have found no evidence for an “obesogenic” feeding style that distinguishes obese and normal weight mothers.65,71,75 Rather, restrictive feeding styles may produce different growth outcomes in the children of obese mothers, who are predisposed to excessive weight gain due to shared genetic and environmental influences.71 A number of studies have found that maternal restriction and/or control during feeding are associated with obesity in the children of obese but not normal weight mothers.10,71,75,76 Further, restrictive feeding styles and the emotional use of food cluster in obese mothers, placing their children at particular risk for excess weight gain.10 The use of restriction by overweight mothers of 5-year-old girls, who themselves had higher EAH than normal weight mothers,71 was associated with increased EAH from 5-9 years of age and higher BMI at age 9 in their daughters.70 Taken together, the differential impact of feeding styles and disinhibited eating on the children of obese mothers indicates that maternal overweight may provide both the predisposition and context for the development of obesogenic eating behaviors in children.71

Conclusion: The early feeding environment of obese mothers and opportunities for intervention

Increasing evidence supports an important role for maternal obesity in the development of childhood obesity and subsequent adult disease. However, critical gaps in the literature remain. Further research is particularly needed to address the complementary feeding practices of overweight and obese mothers and how these practices, in conjunction with shared biology and shared psychosocial and physical feeding environments, may shape the development of appetite, energy intakes, and food preferences during the critical periods of early infancy, the transition to solid foods, and the adoption of the family diet. Many of these pathways linking maternal obesity and feeding practices to child overweight are well described for preschool children; yet, while receiving comparatively less attention, differences in the early feeding practices of obese mothers may be particularly important in the intergenerational transmission of obesity.

The poorer early diet quality with low levels of breastfeeding and higher intakes of high energy and fat foods seen in the infants and young children of obese mothers place them at risk for excess weight gain.38,56 Exposure to these obesogenic early diets also influence appetite regulation, entraining the hypothalamic neural circuitry regulating appetite by inducing permanent changes in the complex pathways linking the hypothalamus, gastrointestinal tract and adipose tissue.77 Along with these physiological impacts, maternal diet modeling,14 the foods available in the household,51 and the emotional climate surrounding infant feeding20 shape later responsiveness to satiety cues and food acceptance. Obese mothers' feeding styles may be more or less responsive to infant hunger and satiety cues and, when combined with early solid feeding and/or poor diet quality, less responsive feeding contributes to intakes in excess of needs and the “over-riding” of the infant's internal satiety cues. Thus, early intervention is needed to stem the development of an obesogenic eating environment and prevent early excess weight gain.

Improving food choice and reducing caloric intake in children at risk for obesity are required for long-term change and, given mothers' influence as the primary food providers on their children's diets, two-generation programs are essential.62 Results from interventions targeting the overweight and obese mothers of obese children indicate that parental role modeling of healthy behaviors has the greatest impact on children's eating and activity behaviors.78 Overweight and obese mothers who modify their food choices are more likely to make comparable changes for their children, resulting in improved toddler diets with lowered intakes of calories, fat, sugar-sweetened beverages and fast foods.78 Further, studies suggest that focusing on improving food-related parenting styles, encouraging mothers to assume leadership roles in changing feeding environments and to grant appropriate child autonomy while remaining firm and supportive, also result in an improved food environment and less sedentary behavior.62 Focusing on supporting breastfeeding, improving the food choices of obese women, and encouraging the development of authoritative feeding styles may improve the quality of the early feeding environment, a critical step for preventing early obesity.

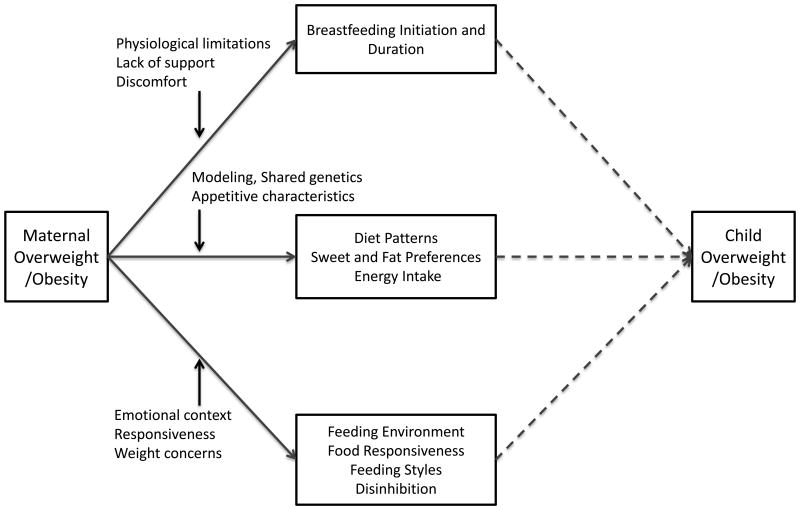

Figure 1. Maternal obesity, feeding behaviors and child obesity risk.

This figure describes the reviewed literature showing feeding differences between overweight/obese mothers and normal weight mothers. Potential mechanisms linking maternal obesity to these feeding practices are shown along the solid pathways. Dashed lines indicate the potential pathways linking maternal feeding behaviors to child overweight/obesity.

Acknowledgments

The author is supported by NIH: NICHD (K01 HD071948-01) and thanks the Carolina Population Center (R24 HD050924) for general support.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. Jama. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu SY, Kim SY, Bish CL. Prepregnancy obesity prevalence in the United States, 2004-2005. Matern Child Health J. 2009 Sep;13(5):614–620. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oken E. Maternal and child obesity: the causal link. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009 Jun;36(2):361–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.03.007. ix-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poston L. Maternal obesity, gestational weight gain and diet as determinants of offspring long term health. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooney K, Ozanne SE. Maternal over-nutrition and offspring obesity predisposition: targets for preventative interventions. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011 Jul;35(7):883–890. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdette HL, Whitaker RC, Hall WC, Daniels SR. Breastfeeding, introduction of complementary foods, and adiposity at 5 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Mar;83(3):550–558. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruager-Martin R, Hyde MJ, Modi N. Maternal obesity and infant outcomes. Early Hum Dev. 2010 Nov;86(11):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss RS, Knight J. Influence of the home environment on the development of obesity in children. Pediatrics. 1999 Jun;103(6):e85. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair NJ, Thompson JM, Black PN, et al. Risk factors for obesity in 7-year-old European children: the Auckland Birthweight Collaborative Study. Arch Dis Child. 2007 Oct;92(10):866–871. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.116855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kral TV, Rauh EM. Eating behaviors of children in the context of their family environment. Physiol Behav. 2010 Jul 14;100(5):567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maes HH, Neale MC, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav Genet. 1997 Jul;27(4):325–351. doi: 10.1023/a:1025635913927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds RM. Childhood Obesity: The Impact of Maternal Obesity on Childhood Obesity. In: Ovesen PG, Jensen DM, editors. Maternal Obesity and Pregnancy. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2012. pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson SM, Godfrey KM. Feeding practices in pregnancy and infancy: relationship with the development of overweight and obesity in childhood. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008 Dec;32(Suppl 6):S4–10. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scaglioni S, Arrizza C, Vecchi F, Tedeschi S. Determinants of children's eating behavior. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Dec;94(6 Suppl):2006S–2011S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson AL. Developmental origins of obesity: early feeding environments, infant growth, and the intestinal microbiome. Am J Hum Biol. 2012 May-Jun;24(3):350–360. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amir LH, Donath S. A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasmussen KM. Association of maternal obesity before conception with poor lactation performance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:103–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson S, Marriott L, Poole J, et al. Dietary patterns in infancy: the importance of maternal and family influences on feeding practice. Br J Nutr. 2007 Nov;98(5):1029–1037. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507750936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage JS, Fisher JO, Birch LL. Parental influence on eating behavior: conception to adolescence. J Law Med Ethics Spring. 2007;35(1):22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrick H, Nicklas TA. A review of family and social determinants of children's eating patterns and diet quality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005 Apr;24(2):83–92. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, et al. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Aug;25(8):1175–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bray GA. Obesity and reproduction. Hum Reprod. 1997 Oct;12(Suppl 1):26–32. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.suppl_1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. Prepregnant overweight and obesity diminish the prolactin response to suckling in the first week postpartum. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5):e465–471. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman DJ, Perez-Escamilla R. Identification of risk factors for delayed onset of lactation. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999 Apr;99(4):450–454. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00109-1. quiz 455-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman DJ, Perez-Escamilla R. Does delayed perception of the onset of lactation shorten breastfeeding duration? J Hum Lact. 1999 Jun;15(2):107–111. doi: 10.1177/089033449901500207. quiz 137-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oddy WH, Li J, Landsborough L, Kendall GE, Henderson S, Downie J. The association of maternal overweight and obesity with breastfeeding duration. J Pediatr. 2006 Aug;149(2):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mok E, Multon C, Piguel L, et al. Decreased full breastfeeding, altered practices, perceptions, and infant weight change of prepregnant obese women: a need for extra support. Pediatrics. 2008 May;121(5):e1319–1324. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendricks K, Briefel R, Novak T, Ziegler P. Maternal and child characteristics associated with infant and toddler feeding practices. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 Jan;106(1 Suppl 1):S135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li R, Zhao Z, Mokdad A, Barker L, Grummer-Strawn L. Prevalence of breastfeeding in the United States: the 2001 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics. 2003 May;111(5 Part 2):1198–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hauff LE, Demerath EW. Body image concerns and reduced breastfeeding duration in primiparous overweight and obese women. Am J Hum Biol. 2012 May-Jun;24(3):339–349. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casazza K, Fontaine KR, Astrup A, et al. Myths, presumptions, and facts about obesity. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368(5):446–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1208051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arenz S, Ruckerl R, Koletzko B, von Kries R. Breast-feeding and childhood obesity--a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 Oct;28(10):1247–1256. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harder T, Bergmann R, Kallischnigg G, Plagemann A. Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Sep 1;162(5):397–403. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics. 2005 May;115(5):1367–1377. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Rasmussen KM, Sorensen TI. Maternal prepregnant body mass index, duration of breastfeeding, and timing of complementary food introduction are associated with infant weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Dec;80(6):1579–1588. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lonnerdal B, Dewey KG. Intake and growth of breast-fed and formula-fed infants in relation to the timing of introduction of complementary foods: the DARLING study. Davis Area Research on Lactation, Infant Nutrition and Growth. Acta Paediatr. 1993 Dec;82(12):999–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartok CJ, Ventura AK. Mechanisms underlying the association between breastfeeding and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009;4(4):196–204. doi: 10.3109/17477160902763309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar;127(3):e544–551. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C, Kaur H, Choi WS, Huang TT, Lee RE, Ahluwalia JS. Additive interactions of maternal prepregnancy BMI and breast-feeding on childhood overweight. Obesity research. 2005 Feb;13(2):362–371. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finley DA, Lonnerdal B, Dewey KG, Grivetti LE. Breast milk composition: fat content and fatty acid composition in vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985 Apr;41(4):787–800. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wojcik KJ. Maternal determinants of childhood obesity: weight gain, smoking, and breastfeeding. In: Freemark M, editor. Contemporary Endocrinology: Pediatric Obesity:Etiology, Pathogenesis and Treatment. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan EL, Smith MS, Grove KL. Perinatal exposure to high-fat diet programs energy balance, metabolism and behavior in adulthood. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;93(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000322038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drake AJ, Reynolds RM. Impact of maternal obesity on offspring obesity and cardiometabolic disease risk. Reproduction. 2010 Sep;140(3):387–398. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stunkard AJ, Berkowitz RI, Schoeller D, Maislin G, Stallings VA. Predictors of body size in the first 2 y of life: a high-risk study of human obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 Apr;28(4):503–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Llewellyn CH, van Jaarsveld CH, Plomin R, Fisher A, Wardle J. Inherited behavioral susceptibility to adiposity in infancy: a multivariate genetic analysis of appetite and weight in the Gemini birth cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Mar;95(3):633–639. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.023671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rising R, Lifshitz F. Relationship between maternal obesity and infant feeding-interactions. Nutr J. 2005;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anzman SL, Rollins BY, Birch LL. Parental influence on children's early eating environments and obesity risk: implications for prevention. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010 Jul;34(7):1116–1124. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, et al. Perception of eating and exercise in children as a function of child and parent weight status. Appetite. 1989 Apr;12(2):105–118. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(89)90100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher JO, Birch LL. Fat preferences and fat consumption of 3- to 5-year-old children are related to parental adiposity. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995 Jul;95(7):759–764. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00212-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beydoun MA, Wang Y. Parent-child dietary intake resemblance in the United States: evidence from a large representative survey. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Jun;68(12):2137–2144. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hart CN, Raynor HA, Jelalian E, Drotar D. The association of maternal food intake and infants' and toddlers' food intake. Child Care Health Dev. 2010 May;36(3):396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oliveria SA, Ellison RC, Moore LL, Gillman MW, Garrahie EJ, Singer MR. Parent-child relationships in nutrient intake: the Framingham Children's Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Sep;56(3):593–598. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papas MA, Hurley KM, Quigg AM, Oberlander SE, Black MM. Low-income, African American adolescent mothers and their toddlers exhibit similar dietary variety patterns. J Nutr Educ Behav Mar-Apr. 2009;41(2):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raynor HA, Van Walleghen EL, Osterholt KM, et al. The relationship between child and parent food hedonics and parent and child food group intake in children with overweight/obesity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011 Mar;111(3):425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee SY, Hoerr SL, Schiffman RF. Screening for infants' and toddlers' dietary quality through maternal diet. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2005 Jan-Feb;30(1):60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ong KK, Emmett PM, Noble S, Ness A, Dunger DB. Dietary energy intake at the age of 4 months predicts postnatal weight gain and childhood body mass index. Pediatrics. 2006 Mar;117(3):e503–508. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brekke HK, van Odijk J, Ludvigsson J. Predictors and dietary consequences of frequent intake of high-sugar, low-nutrient foods in 1-year-old children participating in the ABIS study. Br J Nutr. 2007 Jan;97(1):176–181. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507244460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lewis M, Worobey J. Mothers and toddlers lunch together. The relation between observed and reported behavior. Appetite. 2011 Jun;56(3):732–736. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nguyen VT, Larson DE, Johnson RK, Goran MI. Fat intake and adiposity in children of lean and obese parents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 Apr;63(4):507–513. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wardle J, Guthrie C, Sanderson S, Birch L, Plomin R. Food and activity preferences in children of lean and obese parents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Jul;25(7):971–977. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bayol SA, Farrington SJ, Stickland NC. A maternal ‘junk food’ diet in pregnancy and lactation promotes an exacerbated taste for ‘junk food’ and a greater propensity for obesity in rat offspring. Br J Nutr. 2007 Oct;98(4):843–851. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507812037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Golan M, Crow S. Targeting parents exclusively in the treatment of childhood obesity: long-term results. Obesity research. 2004 Feb;12(2):357–361. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baughcum AE, Powers SW, Johnson SB, et al. Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001 Dec;22(6):391–408. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hodges EA, Johnson SL, Hughes SO, Hopkinson JM, Butte NF, Fisher JO. Development of the responsiveness to child feeding cues scale. Appetite. 2013 Jun;65:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wardle J, Sanderson S, Guthrie CA, Rapoport L, Plomin R. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obes Res. 2002 Jun;10(6):453–462. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jahnke DL, Warschburger PA. Familial transmission of eating behaviors in preschool-aged children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Aug;16(8):1821–1825. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lumeng JC, Burke LM. Maternal prompts to eat, child compliance, and mother and child weight status. J Pediatr. 2006 Sep;149(3):330–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haycraft EL, Blissett JM. Maternal and paternal controlling feeding practices: reliability and relationships with BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Jul;16(7):1552–1558. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berkowitz RI, Moore RH, Faith MS, Stallings VA, Kral TV, Stunkard AJ. Identification of an obese eating style in 4-year-old children born at high and low risk for obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010 Mar;18(3):505–512. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Francis LA, Ventura AK, Marini M, Birch LL. Parent overweight predicts daughters' increase in BMI and disinhibited overeating from 5 to 13 years. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007 Jun;15(6):1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Francis LA, Birch LL. Maternal weight status modulates the effects of restriction on daughters' eating and weight. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 Aug;29(8):942–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Francis LA, Hofer SM, Birch LL. Predictors of maternal child-feeding style: maternal and child characteristics. Appetite. 2001 Dec;37(3):231–243. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fisher JO, Birch LL. Restricting access to foods and children's eating. Appetite. 1999 Jun;32(3):405–419. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Eating in the absence of hunger: a genetic marker for childhood obesity in prepubertal boys? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006 Jan;14(1):131–138. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Powers SW, Chamberlin LA, van Schaick KB, Sherman SN, Whitaker RC. Maternal feeding strategies, child eating behaviors, and child BMI in low-income African-American preschoolers. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006 Nov;14(11):2026–2033. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2004 Oct;114(4):e429–436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1075-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Agostini C. Ghrelin, leptin and the neurometabolic axis of breastfed and formula-fed infants. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:523–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Klohe-Lehman DM, Freeland-Graves J, Clarke KK, et al. Low-income, overweight and obese mothers as agents of change to improve food choices, fat habits, and physical activity in their 1-to-3-year-old children. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007 Jun;26(3):196–208. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]