Abstract

Male urethral stricture disease is prevalent and has a substantial impact on quality of life and health-care costs. Management of urethral strictures is complex and depends on the characteristics of the stricture. Data show that there is no difference between urethral dilation and internal urethrotomy in terms of long-term outcomes; success rates range widely from 8–80%, with long-term success rates of 20–30%. For both of these procedures, the risk of recurrence is greater for men with longer strictures, penile urethral strictures, multiple strictures, presence of infection, or history of prior procedures. Analysis has shown that repeated use of urethrotomy is not clinically effective or cost-effective in these patients. Long-term success rates are higher for surgical reconstruction with urethroplasty, with most studies showing success rates of 85–90%. Many techniques have been utilized for urethroplasty, depending on the location, length, and character of the stricture. Successful management of urethral strictures requires detailed knowledge of anatomy, pathophysiology, proper patient selection, and reconstructive techniques.

Introduction

Male urethral strictures account for about 5,000 inpatient visits and 1.5 million office visits per year in the USA.1 Stricture disease can have a profound impact on quality of life, resulting in infection, bladder calculi, fistulas, sepsis, and ultimately renal failure.1 Studies of the natural history of stricture disease in untreated patients show high rates of disease complications (Box 1). The incidence of urethral stricture has been estimated at 200–1,200 cases per 100,000 individuals, with the incidence sharply increasing in people aged ≥55 years.1 Related costs to the medical system are substantial; the estimated annual health-care expenditures for male urethral stricture disease in the USA were US$191 million in 2000, with an annual health-care expenditure increase of US$6,759 for an insured male with stricture disease.1

Box 1 | Complications of untreated strictures8.

Thick-walled trabeculated bladder (85% incidence)

Acute retention (60% incidence)

Prostatitis (50% incidence)

Epididymo-orchitis (25% incidence)

Hydronephrosis (20% incidence)

Periurethal abscess (15% incidence)

Bladder or urethral stones (10% incidence)

Strictures can be divided into two main types, anterior and posterior, which differ not only in their location, but also in their underlying pathogenesis. In a retrospective analysis of all strictures that had been reconstructed at a single institution, the vast majority of strictures were anterior (92.2%), with most of these occurring in the bulbar urethra (46.9%), followed by penile (30.5%), penile and bulbar (9.9%), and panurethral (4.9%) strictures.2 In this Review, we discuss the epidemiology, pathogenesis, aetiology, evaluation, and management of anterior male urethral strictures. We also consider some current controversies in urethroplasty, such as the management of failed hypospadias repair and long or complex strictures, as well as the use of dorsal versus ventral onlay grafting.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

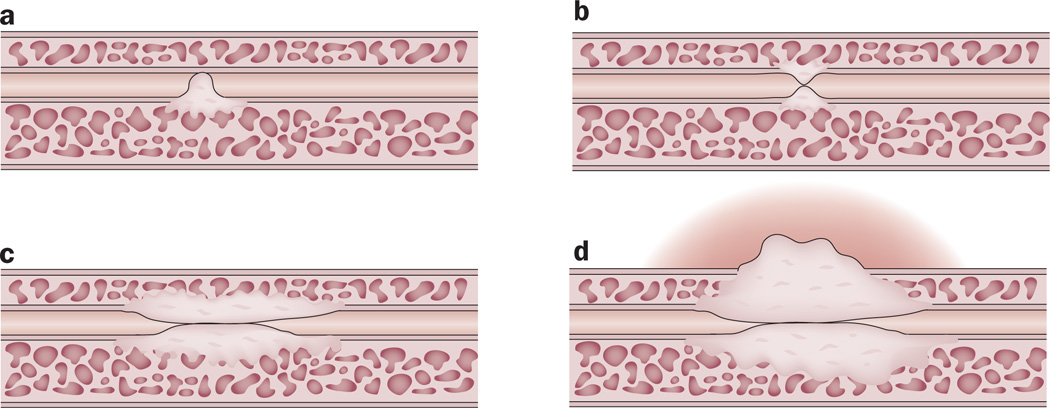

All strictures result from injury to the epithelium of the urethra or underlying corpus spongiosum, which ultimately causes fibrosis during the healing process (Figure 1). The pathological changes associated with strictures show that the normal pseudostratified columnar epithelium is replaced with squamous metaplasia.3 Small tears in this metaplastic tissue result in urinary extravasation, which causes a fibrotic reaction within the spongiosum.4 At the time of injury, this fibrosis can be asymptomatic; however, over time, the fibrotic process can cause further narrowing of the lumen of the urethra, resulting in symptomatic obstructive voiding.

Figure 1.

Stricture pathogenesis. The pathological changes associated with strictures show that the normal pseudostratified columnar epithelium is replaced with squamous metaplasia. a | Small tears in this metaplastic tissue result in urinary extravasation, which causes a fibrotic reaction of the spongiosum. At the time of injury, this fibrosis can be asymptomatic, but the fibrotic process might cause b | further narrowing of the lumen of the urethra in the future, potentially resulting in c | spongiofibrosis d | and extra-spongiofibrosis, as well as symptomatic obstructive voiding symptoms.

Urethral stricture pathology is generally characterized by changes in the extracellular matrix of urethral spongiosal tissue,5 which have been shown upon histologic evaluation of normal and strictured urethral tissue.6 Normal connective tissue is replaced by dense fibres interspersed with fibroblasts and a decrease in the ratio of type III to type I collagen occurs.6 This change is accompanied by a decrease in the ratio of smooth muscle to collagen, as well as significant changes in the synthesis of nitric oxide in strictured urethral tissue.7 Anterior urethral strictures typically occur following trauma or infection, resulting in spongiofibrosis. Through this process, the corpus spongiosum becomes fibrosed, producing a narrowed urethral lumen. If the fibrosis is extensive, it can involve the tissues outside of the corpus spongiosum as well. Posterior urethral stenoses typically result from an obliterative process that causes fibrosis of the posterior urethra, such as iatrogenic injuries from pelvic radiation or radical prostatectomy, or from distraction injuries that occur after trauma, particularly pelvic fractures. These injuries are termed contractures or stenoses, rather than true strictures.

Many types of stricture exist, including iatrogenic strictures (such as those caused by catheterization, instrumentation, and prior hypospadias repair), infectious or inflammatory strictures (for example, caused by gonorrhoea or lichen sclerosis), traumatic strictures (including straddle injuries or pelvic fractures), and congenital or idiopathic strictures (Table 1).8 Iatrogenic causes have been shown to account for almost 50% of idiopathic strictures, which relates to about 30% of all strictures.9 With respect to penile urethral strictures, about 15% are idiopathic, 40% are iatrogenic, 40% are inflammatory, and 5% are related to trauma. For bulbar urethral strictures, about 40% are idiopathic, 35% are iatrogenic, 10% are inflammatory, and 15% are traumatic.8

Table 1.

Incidence of strictures of different aetiologies8

| Aetiology | Penile stricture (%) | Bulbar stricture (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic | 15 | 40 |

| Iatrogenic | 40 | 35 |

| Inflammatory | 40 | 10 |

| Traumatic | 5 | 15 |

Diagnosis and evaluation

Men with symptomatic stricture disease will typically present with obstructive voiding symptoms such as straining, incomplete emptying, and a weak stream; they might also have a history of recurrent UTI, prostatitis, epididymitis, haematuria, or bladder stones. On physical examination, it is necessary to palpate the anterior urethra to identify the depth and density of the scarred tissue. Often patients will have an obstructive voiding pattern on uroflowmetry studies and might also have a high postvoid residual volume suggestive of incomplete emptying. A urinalysis should be obtained in order to rule out infection.

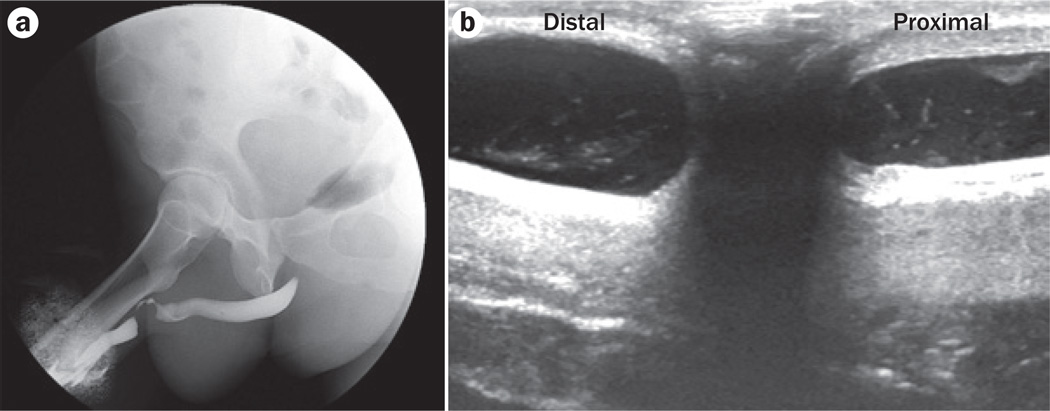

Retrograde urethrography (RUG) and voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) are used to determine the location, length, and severity of the stricture. Typically, narrowing of the urethral lumen is evident at the site of the stricture, with dilation of the urethra proximal to the stricture. A cystoscopy can also be performed if the RUG and VCUG are inconclusive to give an idea as to the location of the stricture and the elasticity and appearance of the urethra. A cystoscopy can be performed either through the meatus (with a paediatric cystoscope or ureteroscope if necessary) or through a suprapubic cystostomy (with a flexible cystoscope) depending on the location and grade of stricture disease. Ultrasonography can be used as an adjunct to determine the length and degree of spongiofibrosis, and can influence the operative approach.10,11 Ultrasonography can be performed either preoperatively or intraoperatively. One advantage of intraoperative ultrasonography is that it can be performed with hydrodistension once the patient is anaesthetized, enabling accurate evaluation of anterior strictures and avoiding an additional investigation during preoperative evaluation. This approach also assesses the stricture at the time of repair and, therefore, at the maximum severity of the stricture.

These imaging modalities are important, not only to determine the characteristics of the stricture itself, but also to evaluate the urethra both proximal and distal to the stricture and ensure that all diseased portions of the urethra are included in the repair (Figure 2). Patients should not have a urethral catheter or self-catheterize for at least 6 weeks before the procedure in order to allow maximum stricturing to take place before repair and ensure that the stricture is stable at the time of operative intervention. If necessary, a suprapubic cystostomy can be performed 6–12 weeks before the repair. This type of diversion can also be helpful in cases of retention or diversion of infected urine, especially with the presence of urethral abscesses or fistulas.

Figure 2.

Imaging for stricture. Imaging modalities such as a | retrograde urethrogram and b | intraoperative ultrasonography are important for determining the characteristics of the stricture and for evaluating the urethra both proximal and distal to the stricture in order to ensure that all portions of the urethra that are diseased are included in the repair.

Management

Urethral dilation

Several methods for urethral dilation exist, including dilation with a balloon, filiform and followers, urethral sounds, or self-dilation with catheters. Overall, studies have shown no difference in recurrence rates following urethral dilation versus internal urethrotomy.12,13 One prospective randomized controlled study of men with urethral stricture treated with filiform dilation or internal urethrotomy reported no significant difference in stricture-free rates at 3 years or in the median time to recurrence for these two approaches.14,15 Rates of complications and failure at the time of the procedure do not differ significantly between dilation and internal urethrotomy,13 although complications associated with urethral dilation might be more likely to occur in patients who present with urinary retention.13

Internal urethrotomy

Direct vision internal urethrotomy (DVIU) is performed by making a cold-knife transurethral incision to release scar tissue, allowing the tissue to heal by secondary intention at a larger calibre and thereby increasing the size of the urethral lumen. Many studies have evaluated the benefit of placing a urethral catheter after urethrotomy, although no consensus has been reached to date on whether to leave a catheter and, if so, for what duration.16–24 Internal urethrotomy success rates vary widely, ranging from 8–80%, depending on patient selection, length of follow-up assessment, and methods of determining success and recurrence.14,18–22,25–29 Overall long-term success rates are estimated to be just 20–30%.22,30

In general, recurrence is more likely with longer strictures; the risk of recurrence at 12 months is 40% for strictures shorter than 2 cm, 50% for strictures between 2–4 cm, and 80% for strictures longer than 4 cm.12 For each additional 1 cm of stricture, the risk of recurrence has been shown to increase by 1.22 (95% CI 1.05–1.43).12 Recurrence rates also vary according to stricture location; 58% of bulbar strictures will recur after urethrotomy, compared with 84% for penile strictures and 89% for membranous strictures.22 Risk of stricture recurrence is greatest at 6 months; however, if the stricture has not recurred by 1 year, the risk of recurrence is significantly decreased.12 Data from one study suggests if the stricture has not recurred within the first 3 months after a single dilation or urethrotomy, the stricture- free rate is 50–60% for up to 4 years of follow-up assessment.14 Repeat urethrotomy is known to be associated with progressively worse outcomes; in one study, the stricture-free rate for a second procedure was found to be 30–50% at 2 years, 0–40% at 4 years, and 0% at 2 years following a third procedure.14,21,22,25,31

Overall, men with the highest success rates have strictures in the bulbar urethra that are primary strictures of <1.5 cm in length and are not associated with spongiofibrosis.21,22,31 Risk factors for recurrence include previous internal urethrotomy, strictures located within the penile or membranous urethra, strictures of >2 cm in length, multiple strictures, UTI at the time of procedure, and strictures associated with extensive periurethral spongiofibrosis.13,16,21,22,28,31,32 These data can be used to help predict which patients might be good candidates for urethrotomy or dilation.

Some urologists have suggested that self- catheterization following urethrotomy might decrease recurrence rates, reporting delayed time to recurrence and decreased rates of recurrence with self-catheterization.33–36 However, other studies have shown that self-dilation does not decrease recurrence rates (as it is required on a long-term basis to prevent recurrence), and that self-dilation is associated with significant long-term complications and high dropout rates.21,31

The main complications following urethrotomy include recurrence, perineal haematoma, urethral haemorrhage, and extravastion of irrigation fluid into perispongiosal tissues. With deep incisions at the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions, there is also a risk of entering the corpus cavernosum and creating fistulas between the corpus spongiosum and cavernosa, leading to erectile dysfunction.21 One meta-analysis of complications of cold-knife urethrotomy established an overall complication rate of 6.5%; the most common complications were erectile dysfunction (5%), urinary incontinence (4%), extravasation (3%), UTI (2%), haematuria (2%), epididymitis (0.5%), urinary retention (0.4%), and scrotal abscess (0.3%).37 Of note, erectile dysfunction is particularly common in patients with long and dense strictures requiring extensive incision.38,39 In general, complications associated with internal urethrotomy are more likely to occur in men with a positive urine culture, a history of urethral trauma, multiple stricture segments, and long (>2 cm) strictures.13

Injectable agents

Some studies have evaluated the efficacy of agents injected into the scar tissue at the time of internal urethrotomy to decrease recurrence rates. Mitomycin C has shown promise when used for both anterior urethral strictures and incision of bladder neck contractures.40,41 Studies evaluating the use of triamcinolone injection have shown a significant decrease in both time to recurrence and recurrence rate at 12 months without any significant increase in rates of perioperative complications.42,43

Laser urethrotomy

In addition to cold-knife internal urethrotomy, studies have evaluated the use of lasers for urethrotomy.37,44–54 Many types of lasers have been utilized, including carbon dioxide, argon, potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP), neodymium- doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:Yag), holmium:Yag, and excimer lasers. These lasers each use different technologies and offer differing depths of tissue penetration. As such, lasers pose distinctive risks depending on their mechanism of action, such as carbon dioxide embolus with the use of a gas cystoscope for the carbon dioxide laser, and peripheral tissue injury due to thermal necrosis with the use of the argon and Nd:Yag lasers. Overall, data seem to show equivalence in terms of both complication and success rates for these different lasers.37 Currently, there is no clear consensus on which laser or technique is best to use, but a survey conducted in 2011 showed that nearly 20% of urologists reported using laser urethrotomy to manage anterior urethral strictures.55

A meta-analysis of complications associated with laser urethrotomy reported an overall complication rate of 12%, which compares unfavourably to the 6.5% incidence reported for cold-knife urethrotomy.37 Common complications included UTI (11% incidence), urinary retention (9% incidence), haematuria (5% incidence), dysuria (5% incidence), urinary extravasation (3% incidence), UTI (3% incidence), urinary incontinence (2% incidence), and urinary fistula (1.5% incidence).

Urethral stents

The use of urethral stents following dilation or internal urethrotomy has also been explored. Temporary stents such as the Spanner® stent (SRS Medical, USA) require exchange every 3–12 months depending on the type of stent, and are more suitable for men with posterior urethral obstruction.56 Permanent stents, such as the Urolume® (Endo Health Solutions, USA) and Memotherm® (Bard, Germany) stent, are placed into the bulbar urethra and incorporated into the wall of the urethra.57–59 However, use of these stents has been largely abandoned and, in some countries, these stents have been removed from the market because of limited use and high rates of complications such as perineal pain, stent migration, stent obstruction (owing to tissue hyperplasia or stone encrustation), incontinence, and infection.21,60–63

Urethroplasty

Many studies have sought to determine the effectiveness of internal urethrotomy compared with open reconstructive urethroplasty. Although none of these studies have been true randomized controlled trials, they suggest that long-term success rates are much higher for urethroplasty (85–90%) than for urethrotomy (20–30%).15,21 In fact, available data suggest that urethroplasty is the most effective method for definitive correction of urethral stricture disease and this approach is generally considered to be the gold-standard treatment.8,15,64

In an era when health-care costs are heavily scrutinized, several studies have also examined the costs associated with different methods of treatment and have reported different results. Two studies have shown that the most cost-effective method is a first attempt at internal urethrotomy followed by urethroplasty for recurrence.29,65 However, another group showed that immediate urethroplasty became more cost-effective when the predicted success rate of the internal urethrotomy was <35%, suggesting that men who are predicted to have recurrence after internal urethrotomy should be offered immediate urethroplasty instead.65 To that end, another group found that immediate urethroplasty as a first procedure is the most cost-effective method.66

One question that has been raised is whether a prior internal urethrotomy makes urethroplasty more difficult, thereby decreasing urethroplasty success rates. In one retrospective study of men with bulbar urethral strictures, researchers found that success rates were equivalent in individuals undergoing primary (immediate) and secondary (following failed urethrotomy) urethroplasties.67 Risk factors associated with failure included incomplete excision of scar tissue, anastomotic tension, and the presence of lichen sclerosis.68,69 The majority of the data show that prior urethral intervention does not affect the likelihood of success and that, even with prior radiation, success rates of up to 90% can be achieved.69–72 Studies have also shown excellent success rates for redo urethroplasty (78% in one large series).73 Predictors of failure following repeat urethroplasty include a history of hypospadias repair, lichen sclerosis, and a history of two or more failed prior urethroplasties.74

Several techniques have been used for urethroplasty, including excision and primary re-anastomosis, onlay grafting, and the use of flaps. Both short-term and long-term success rates are highest for anastomotic urethroplasties, with 15-year recurrence and complication rates of 14% and 7%, respectively, in one series, and 5–10% recurrence rates in another series.75 One review found equivalent success rates for free grafts (84.3%) and flaps (85.9%).76–78 Other groups have suggested that the use of flaps is superior to grafts for men with a history of prior surgery or radiation, as these prior interventions can affect graft take.79

End-to-end anastomotic urethroplasty

An end-to-end anastomotic repair technique has traditionally been used for bulbar strictures that are <2 cm in length.64 Anastomotic urethroplasty scores highly for both objective and patient-centred subjective criteria, with most studies reporting success rates of between 90–95%.70,77,78 Recurrent strictures in men who have undergone urethroplasty are generally treated with direct vision internal urethrotomy alone, resulting in good long-term success rates.80 Additionally, some clinicians have suggested that younger men might have better tissue compliance, increasing the chances of successful excision and primary re-anastomosis for fairly long strictures.81

Onlay free graft

Substitution or graft urethroplasties are traditionally used for strictures longer than 2 cm for which an anasto-motic urethroplasty is not feasible owing to anastamotic tension. Historically, preputial skin grafts were the mainstay of grafting material until oral mucosal grafts became popularized in the early 1990s.82–84 However, the principle of grafting has remained the same since the beginning, namely that the local tissue must have a healthy blood supply to support the graft. One-stage grafting urethroplasty utilizes the vascularity of spongiosal tissue ventrally or corpora cavernosa dorsally to support the free graft. Overall success rates for onlay grafting approach 90%, depending on the location of the onlay graft. Success rates for penile strictures range from 75–90%, depending on the length of the stricture and whether a one-stage or two-stage procedure is performed, whereas success rates for bulbar onlay repair are consistently around 88%.85 Several types of tissue can be used as onlay grafts, including full- thickness and partial- thickness skin grafts, bladder urothelial grafts, oral mucosal (buccal or lingual) grafts, and rectal mucosal grafts. Oral grafts have become the most common graft type, owing to their short harvest time, hairlessness, low morbidity, durability, and excellent success rates.86–90 One retrospective study of one-stage bulbar urethroplasty reported higher success rates with oral mucosal grafts than with penile skin grafts.91

One controversy in this field relates to whether the free graft should be placed on the ventral or the dorsal surface of the urethra.89,92 Some practitioners favour dorsal placement of grafts throughout the bulbar urethra, whereas others only use dorsal placement in the distal or mid- bulbar urethra, preferring to place ventral grafts proximally where the corpus spongiosum is thickest. Proponents for ventral grafting argue that the technique is technically easier and requires less dissection and mobilization of the urethra than dorsal grafting.93,94 Proponents of dorsal grafting, on the other hand, argue that the corpus spongiosum provides greater mechanical support for dorsal onlay and, therefore, a reduced risk of diverticula formation, as well as offering a larger calibre of reconstructed urethra and the opportunity for neovascularization.95 Several studies have shown similar success rates for dorsal and ventral onlay grafting,93,94,96–103 ranging from 84–100%.68,104–106

Pedicled flap

In 1968, Orandi presented his experience of using an inversion skin graft to carry out a one-stage urethroplasty at the British Association of Urological Surgeons meeting.107 Over a decade later, Quartey published his experience of using distal penile or preputial skin as vascularized island flaps in urethral reconstruction.108,109 In 1993, McAninch described a modified technique utilizing a circular fasciocutaneous flap from the distal penile skin.110,111 Similar to skin flaps described previously, this technique relies on the blood supply from Buck’s fascia and can be used along the entire penile and bulbar urethra. In addition, it can be used in circumcised men who do not have preputial skin for repair.

It should be noted that, in general, the use of skin flaps for urethral reconstruction is more technically challenging than substitution urethral surgery. For men with an average stricture length of 9 cm, the initial overall success rate of fasciocutaneous flap reconstruction was 79% in one study, with recurrent stricture noted in 13% of onlay grafts and 58% of tubularized repairs.112 The overall long-term success rate, including repeat urethroplasty or urethrotomy, has been reported to be 85–95%.112,113 Most studies show that free-grafts and pedicled skin-flap reconstructions have equivalent success rates in experienced hands.76,114

Urethroplasty complications

Complications are rare, but include erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction, chordee, wound infections, UTIs, fistula development, neuropraxia, and incontinence. Given the dissection required by urethroplasty that inevitably injures corporal blood supply and innervation, it is unsurprising that one of the main complications is short-term erectile dysfunction. Erectile function has been shown to decrease at 3 months postoperatively but generally returns by 6 months. One year after surgical reconstruction, many studies have shown no significant difference in erectile function compared with preoperative function.115,116 In fact, some studies have shown improvement in ejaculation following urethroplasty.115–117 Data suggest that the risk of de novo dysfunction is very low, with an incidence of just 1%.118 Risk factors for the development of erectile dysfunction after repair include posterior urethral stenoses and an end-to-end anastomosis.116

Management of complex urethral strictures

Hypospadias failures

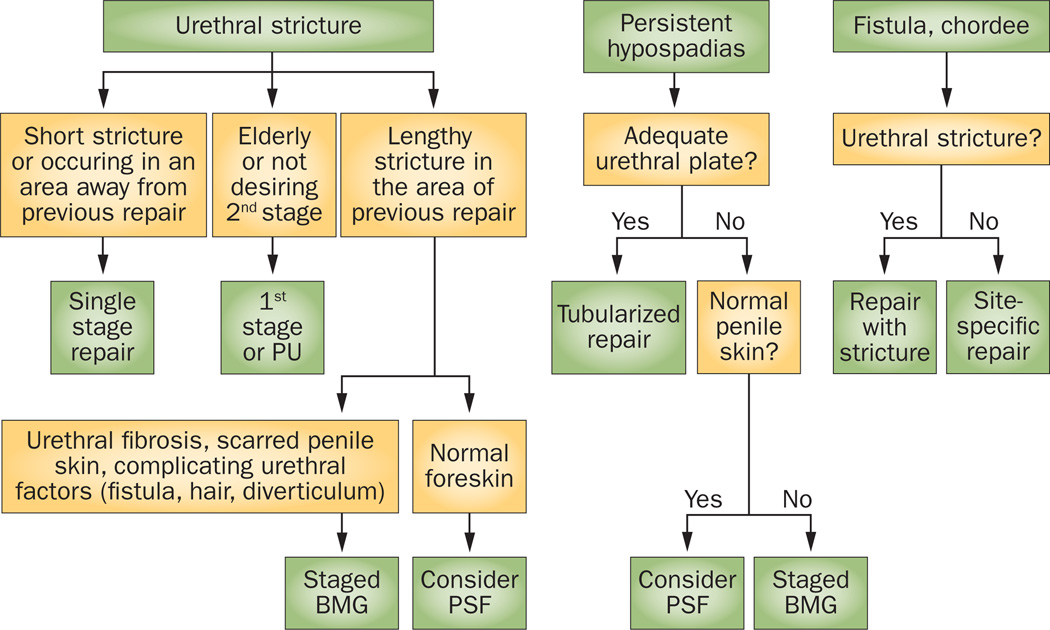

Adults who develop strictures after hypospadias repair as a child pose particular problems for stricture repair.119,120 Repairs on these individuals are difficult because of scarring, immobility, inflammation, poor blood supply, and penile and urethral shortening from prior surgery. Nearly 15% of men treated for urethral strictures and over 50% of those treated for penile urethral stricture have a history of failed hypospadias repair.121 Studies evaluating reconstruction for failed hypospadias have shown success rates ranging from 75–88%.121–123 One group performed a retrospective review of urethroplasties performed on adult hypospadiacs, finding that the initial success rate for treatment was 50%; with additional procedures, this success rate ultimately increased to 76%.123 Another retro-spective chart analysis of men from two tertiary centres in Europe reported an ultimate success rate of 88%, with a median of five surgical operations required to achieve this final outcome.121 Given the complexity of these repairs, one group produced an algorithm based on their own clinical experience to guide surgical management of these men (Figure 3).123 It is important to also note that urethral strictures are not the only complications faced by this population; chordee, fistulae, obstruction, recurrent hypospadias, and diverticulum are also common.124

Figure 3.

Algorithm of general strategy for surgical management of common presenting problems in men with previous hypospadias treatment. Abbreviations: BMG, buccal mucosa graft; PSF, penile skin flap; PU, perineal urethrostomy. Permission obtained from Elsevier Ltd © Myers, J. B. et al J. Urol188, 459–463 (2012).

Long complex strictures

For men with lichen sclerosis or long (>4 cm in length) complex strictures, or those who have failed prior urethroplasty, a two-stage repair with the use of an onlay graft might result in better success rates owing to higher failure rates with one-stage repair in these men.125 In the first stage, an onlay graft is placed on the urethra and, if needed, the patient can undergo a temporary perineal urethrostomy before completion of the second-stage tubularization. Strictures that are associated with local tissue adversity—for example, in men with a prior history of fistula, abscess, radiation, or malignancy—are also more likely to be successfully repaired using a two-stage repair.85,126,127

Posterior urethral stenosis

Posterior urethral stenoses are usually the result of pelvic fracture injury and can also be challenging to manage. On account of their location in the posterior urethra, extensive discussion is beyond the scope of this Review. In general, these stenoses can be difficult to manage because of inflammation and scarring caused by previous trauma, and repair can sometimes require corporal splitting, partial pubectomy, and a combined transabdominal approach.79 One retrospective study found that 35% of men undergoing posterior urethroplasty had undergone a prior failed repair, 22% required partial pubectomy, and 4% required a combined abdominal–perineal approach.70 Ultimately, these repairs all had good outcomes, with 42% requiring a single urethrotomy, resulting in an overall success rate of 93% (including a single DVIU).70

Conclusions

Urethral stricture disease is common and accounts for substantial morbidity and cost to the medical system. Diagnosis and planned repair of strictures involves the use of imaging modalities such as retrograde urethrography. Several methods are available for managing strictures, including urethral dilation, internal urethrotomy, and urethroplasty. Urethral dilation and urethrotomy seem to have equivalent success rates, which are substantially lower than the long-term success rates reported for definitive surgical repair with urethroplasty. Cost-effectiveness analysis supports the early use of urethroplasty (after one failed internal urethrotomy), given that the failure rate of urethrotomy increases substantially with repeated procedures. Urethral reconstruction can be accomplished using a variety of techniques, namely anastomotic, flap, and graft repairs. Choice of technique should be based on the length, location, and character of the stricture in order to achieve optimal success. Controversies still remain regarding the relative efficacies of these techniques and the management of complex strictures; further work is needed to address these issues.

Key points.

Male urethral strictures are common and have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life and health-care costs

Studies such as retrograde urethrography, voiding cystourethrography, and intraoperative ultrasonography can be helpful for determining the best operative approach and management plan

Urethral dilation and internal urethrotomy have similar rates of success, with long-term success rates of 20–30%

Repeated internal urethrotomy is not clinically effective or cost-effective

Long-term success rates are high for urethroplasty, generally ranging from 85–90%

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

L. A. Hampson and B. N. Breyer researched the literature for this article. L. A. Hampson wrote the article, discussed the article with colleagues, and edited the final manuscript. B. N. Breyer and J. W. McAninch contributed towards discussions of contents and reviewed the manuscript prior to publication.

References

- 1.Santucci RA, Joyce GF, Wise M. Male urethral stricture disease. J. Urol. 2007;177:1667–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palminteri E, et al. Contemporary urethral stricture characteristics in the developed world. Urology. 2013;81:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers RM, Baitera B. The anatomy of the urethral stricture. Br. J. Urol. 1977;49:545–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1977.tb04203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh M, Blandy JP. The pathology of urethral stricture. J. Urol. 1976;115:673–676. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavalcanti A, Costa WS, Baskin LS, McAninch JA, Sampaio FJB. A morphometric analysis of bulbar urethral strictures. BJU Int. 2007;100:397–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baskin LS, et al. Biochemical characterization and quantitation of the collagenous components of urethral stricture tissue. J. Urol. 1993;150:642–647. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavalcanti A, Yucel S, Deng DY, McAninch JW, Baskin LS. The distribution of neuronal and inducible nitric oxide synthase in urethral stricture formation. J. Urol. 2004;171:1943–1947. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000121261.03616.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Urethral strictures. BJU Int. 2011;107:6–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lumen N, et al. Etiology of urethral stricture disease in the 21st century. J. Urol. 2009;182:983–987. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckley JC, Wu AK, McAninch JW. Impact of urethral ultrasonography on decision-making in anterior urethroplasty. BJU Int. 2012;109:438–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAninch JW, Laing FC, Jeffrey RB. Sonourethrography in the evaluation of urethral strictures: a preliminary report. J. Urol. 1988;139:294–297. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42391-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steenkamp JW, Heyns CF, De Kock M. Internal urethrotomy versus dilation as treatment for male urethral strictures: a prospective, randomized comparison. J. Urol. 1997;157:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steenkamp JW, Heyns CF, De Kock M. Outpatient treatment for male urethral strictures—dilatation versus internal urethrotomy. S. Afr. J. Surg. 1997;35:125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heyns CF, Steenkamp JW, de Kock ML, Whitaker P. Treatment of male urethral strictures: is repeated dilation or internal urethrotomy useful? J. Urol. 1998;160:356–358. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)62894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong SSW, Narahari R, O’Riordan A, Pickard R. Simple urethral dilatation, endoscopic urethrotomy, and urethroplasty for urethral stricture disease in adult men. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010:CD006934. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006934.pub2. Issue 1. Art. No. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albers P, Fichtner J, Bruhl P, Muller SC. Long-term results of internal urethrotomy. J. Urol. 1996;156:1611–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlton FE, Scardino PL, Quattlebaum RB. Treatment of urethral strictures with internal urethrotomy and 6 weeks of silastic catheter drainage. J. Urol. 1974;111:191–193. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sachse H. [Cystoscopic transurethral incision of urethral stricture with a sharp instrument (author’s transl)] MMW Munch Med. Wochenschr. 1974;116:2147–2150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipsky H, Hubmer G. Direct vision urethrotomy in the management of urethral strictures. Br. J. Urol. 1977;49:725–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1977.tb04561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iversen Hansen R, Guldberg O, Møller I. Internal urethrotomy with the Sachse urethrotome. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 1981;15:189–191. doi: 10.3109/00365598109179600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naudé AM, Heyns CF. What is the place of internal urethrotomy in the treatment of urethral stricture disease? Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol. 2005;2:538–545. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pansadoro V, Emiliozzi P. Internal urethrotomy in the management of anterior urethral strictures: long-term followup. J. Urol. 1996;156:73–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hjortrup A, Sørensen C, Sanders S, Moesgaard F, Kirkegaard P. Strictures of the male urethra treated by the Otis method. J. Urol. 1983;130:903–904. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desmond AD, Evans CM, Jameson RM, Woolfenden KA, Gibbon NO. Critical evaluation of direct vision urethrotomy by urine flow measurement. Br. J. Urol. 1981;53:630–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1981.tb03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santucci R, Eisenberg L. Urethrotomy has a much lower success rate than previously reported. J. Urol. 2010;183:1859–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boccon Gibod L, Le Portz B. Endoscopic urethrotomy: does it live up to its promises? J. Urol. 1982;127:433–435. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giannakopoulos X, Grammeniatis E, Gartzios A, Tsoumanis P, Kammenos A. Sachse urethrotomy versus endoscopic urethrotomy plus transurethral resection of the fibrous callus (Guillemin’s technique) in the treatment of urethral stricture. Urology. 1997;49:243–247. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pain JA, Collier DG. Factors influencing recurrence of urethral strictures after endoscopic urethrotomy: the role of infection and peri-operative antibiotics. Br. J. Urol. 1984;56:217–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1984.tb05364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenwell TJ, et al. Repeat urethrotomy and dilation for the treatment of urethral stricture are neither clinically effective nor cost-effective. J. Urol. 2004;172:275–277. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132156.76403.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santucci RA, McAninch JW. Actuarial success rate of open urethral stricture repair in 369 patient open repairs, compared to 210 DIV or dilation; Presented at the 2001 AUA meeting. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubey D. The current role of direct vision internal urethrotomy and self-catheterization for anterior urethral strictures. Indian J. Urol. 2011;27:392. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.85445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone AR, et al. Optical urethrotomy—a 3-year experience. Br. J. Urol. 1983;55:701–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1983.tb03409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tunc M, et al. A prospective, randomized protocol to examine the efficacy of postinternal urethrotomy dilations for recurrent bulbomembranous urethral strictures. Urology. 2002;60:239–244. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01737-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauritzen M, et al. Intermittent self-dilatation after internal urethrotomy for primary urethral strictures: a case-control study. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 2009;43:220–225. doi: 10.1080/00365590902835593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kjaergaard B, et al. Prevention of urethral stricture recurrence using clean intermittent self-catheterization. Br. J. Urol. 1994;73:692–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb07558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roosen JU. Self-catheterization after urethrotomy. Urol. Int. 1993;50:90–92. doi: 10.1159/000282459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin T, Li H, Jiang L-H, Wang L, Wang K-J. Safety and efficacy of laser and cold knife urethrotomy for urethral stricture. Chin. Med. J. 2010;123:1589–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDermott DW, Bates RJ, Heney NM, Althausen A. Erectile impotence as complication of direct vision cold knife urethrotomy. Urology. 1981;18:467–469. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(81)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graversen PH, Rosenkilde P, Colstrup H. Erectile dysfunction following direct vision internal urethrotomy. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 1991;25:175–178. doi: 10.3109/00365599109107943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanni AJ, Zinman LN, Buckley JC. Radial urethrotomy and intralesional mitomycin c for the management of recurrent bladder neck contractures. J. Urol. 2011;186:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazdak H, Meshki I, Ghassami F. Effect of mitomycin C on anterior urethral stricture recurrence after internal urethrotomy. Eur. Urol. 2007;51:1089–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tavakkoli Tabassi K, Yarmohamadi A, Mohammadi S. Triamcinolone injection following internal urethrotomy for treatment of urethral stricture. Urol. J. 2011;8:132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazdak H, et al. Internal urethrotomy and intraurethral submucosal injection of triamcinolone in short bulbar urethral strictures. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2010;42:565–568. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dutkiewicz SA, Wroblewski M. Comparison of treatment results between holmium laser endourethrotomy and optical internal urethrotomy for urethral stricture. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2012;44:717–724. doi: 10.1007/s11255-011-0094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atak M, et al. Low-power holmium:YAG laser urethrotomy for urethral stricture disease: comparison of outcomes with the cold-knife technique. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2011;27:503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hussain M, Lal M, Askari SH, Hashmi A, Rizvi SAH. Holmium laser urethrotomy for treatment of traumatic stricture urethra: a review of 78 patients. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2010;60:829–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vicente J, Salvador J, Caffaratti J. Endoscopic urethrotomy versus urethrotomy plus Nd-YAG laser in the treatment of urethral stricture. Eur. Urol. 1990;18:166–168. doi: 10.1159/000463901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Wang Z, Yang B, Yang Q, Sun Y. Thulium laser urethrotomy for urethral stricture: A preliminary report. Lasers Surg. Med. 2010;42:620–623. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jabłonowski Z, Ke¸dzierski R, Mie¸ kos E, Sosnowski M. Comparison of neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser treatment with cold knife endoscopic incision of urethral strictures in male patients. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2010;28:239–244. doi: 10.1089/pho.2009.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamp S, et al. Low-power holmium:YAG laser urethrotomy for treatment of urethral strictures: functional outcome and quality of life. J. Endourol. 2006;20:38–41. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hossain AZ, Khan SA, Hossain S, Salam MA. Holmium laser urethrotomy for urethral stricture. Bangladesh Med. Res. Counc. Bull. 2004;30:78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becker HC, Miller J, Nöske HD, Klask JP, Weidner W. Transurethral laser urethrotomy with argon laser: experience with 900 urethrotomies in 450 patients from 1978 to 1993. Urol. Int. 1995;55:150–153. doi: 10.1159/000282774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turek PJ, Malloy TR, Cendron M, Carpiniello VL, Wein AJ. KTP-532 laser ablation of urethral strictures. Urology. 1992;40:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bloiso G, Warner R, Cohen M. Treatment of urethral diseases with neodymium:Yag laser. Urology. 1988;32:106–110. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(88)90308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferguson GG, Bullock TL, Anderson RE, Blalock RE, Brandes SB. Minimally invasive methods for bulbar urethral strictures: a survey of members of the American Urological Association. Urology. 2011;78:701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McKenzie P, Badlani G. Critical appraisal of the Spanner™ prostatic stent in the treatment of prostatic obstruction. Med. Devices (Auckl.) 2011;4:27–33. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milroy E, Allen A. Long-term results of urolume urethral stent for recurrent urethral strictures. J. Urol. 1996;155:904–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sertcelik MN, Bozkurt IH, Yalcinkaya F, Zengin K. Long-term results of permanent urethral stent Memotherm implantation in the management of recurrent bulbar urethral stenosis. BJU Int. 2011;108:1839–1842. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sertcelik N, Sagnak L, Imamoglu A, Temel M, Tuygun C. The use of self-expanding metallic urethral stents in the treatment of recurrent bulbar urethral strictures: long-term results. BJU Int. 2001;86:686–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsiao KC, et al. Direct vision internal urethrotomy for the treatment of paediatric urethral strictures: analysis of 50 patients. J. Urol. 2003;170:952–955. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000082321.98172.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi EK, et al. Management of recurrent urethral strictures with covered retrievable expandable nitinol stents: long-term results. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007;189:1517–1522. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hussain M, Greenwell TJ, Shah J, Mundy A. Long-term results of a self-expanding wallstent in the treatment of urethral stricture. BJU Int. 2004;94:1037–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Vocht TF, Van Venrooij GEPM, Boon TA. Self-expanding stent insertion for urethral strictures: a 10-year follow-up. BJU Int. 2003;91:627–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jordan GH, McCammon KA. Surgery of the Penis and Urethra. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. pp. 956–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wright JL, Wessells H, Nathens AB, Hollingworth W. What is the most cost-effective treatment for 1 to 2-cm bulbar urethral strictures: Societal approach using decision analysis. Urology. 2006;67:889–893. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rourke KF, Jordan GH. Primary urethral reconstruction: the cost minimized approach to the bulbous urethral stricture. J. Urol. 2005;173:1206–1210. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154971.05286.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Lazzeri M, Guazzoni G, Turini D. Long-term outcome of urethroplasty after failed urethrotomy versus primary repair. J. Urol. 2001;165:1918–1919. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200106000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levine LA, Strom KH, Lux MM. Buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty for anterior urethral stricture repair: evaluation of the impact of stricture location and lichen sclerosus on surgical outcome. J. Urol. 2007;178:2011–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koraitim MM. Failed posterior urethroplasty: lessons learned. Urology. 2003;62:719–722. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cooperberg MR, McAninch JW, Alsikafi NF, Elliott SP. Urethral reconstruction for traumatic posterior urethral disruption: outcomes of a 25-year experience. J. Urol. 2007;178:2006–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh BP, et al. Impact of prior urethral manipulation on outcome of anastomotic urethroplasty for post-traumatic urethral stricture. Urology. 2010;75:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glass AS, McAninch JW, Zaid UB, Cinman NM, Breyer BN. Urethroplasty after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2012;79:1402–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blaschko SD, McAninch JW, Myers JB, Schlomer BJ, Breyer BN. Repeat urethroplasty after failed urethral reconstruction: outcome analysis of 130 patients. J. Urol. 2012;188:2260–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martínez-Piñeiro JA, et al. Excision and anastomotic repair for urethral stricture disease: experience with 150 cases. Eur. Urol. 1997;32:433–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andrich DE, Dunglison N, Greenwell TJ, Mundy AR. The long-term results of urethroplasty. J. Urol. 2003;170:90–92. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000069820.81726.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wessells H, McAninch JW. Current controversies in anterior urethral stricture repair: free-graft versus paedicled skin-flap reconstruction. World J. Urol. 1998;16:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s003450050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eltahawy EA, Virasoro R, Schlossberg SM, McCammon KA, Jordan GH. Long-term followup for excision and primary anastomosis for anterior urethral strictures. J. Urol. 2007;177:1803–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Park S, McAninch JW. Straddle injuries to the bulbar urethra: management and outcomes in 78 patients. J. Urol. 2004;171:722–725. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000108894.09050.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Andrich DE, Mundy AR. What is the best technique for urethroplasty? Eur. Urol. 2008;54:1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Santucci RA, Mario LA, Aninch JWMC. Anastomotic urethroplasty for bulbar urethral stricture: analysis of 168 patients. J. Urol. 2002;167:1715–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morey AF, Kizer WS. Proximal bulbar urethroplasty via extended anastomotic approach—what are the limits? J. Urol. 2006;175:2145–2149. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00259-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.El-Kasaby AW, et al. The use of buccal mucosa patch graft in the management of anterior urethral strictures. J. Urol. 1993;149:276–278. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bürger RA, et al. The buccal mucosal graft for urethral reconstruction: a preliminary report. J. Urol. 1992;147:662–664. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dessanti A, Rigamonti W, Merulla V, Falchetti D, Caccia G. Autologous buccal mucosa graft for hypospadias repair: an initial report. J. Urol. 1992;147:1081–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mangera A, Patterson JM, Chapple CR. A systematic review of graft augmentation urethroplasty techniques for the treatment of anterior urethral strictures. Eur. Urol. 2011;59:797–814. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maarouf AM, et al. Buccal versus lingual mucosal graft urethroplasty for complex hypospadias repair. J. Paed. Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.08.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Lumen N, Oosterlinck W, Hoebeke P. Urethral reconstruction using buccal mucosa or penile skin grafts: systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol. Int. 2012;89:387–394. doi: 10.1159/000341138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Markiewicz MR, et al. The oral mucosa graft: a systematic review. J. Urol. 2007;178:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barbagli G, Sansalone S, Djinovic R, Romano G, Lazzeri M. Current controversies in reconstructive surgery of the anterior urethra: a clinical overview. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2012;38:307–316. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382012000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barbagli G. When and how to use buccal mucosa grafts. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2004;56:189–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barbagli G, Morgia G, Lazzeri M. Retrospective outcome analysis of one-stage penile urethroplasty using a flap or graft in a homogeneous series of patients. BJU Int. 2008;102:853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zimmerman WB, Santucci RA. Buccal mucosa urethroplasty for adult urethral strictures. Indian J. Urol. 2011;27:364–370. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.85441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kellner DS, Fracchia JA, Armenaka NA. Ventral onlay buccal mucosal grafts for anterior urethral strictures: long-term followup. J. Urol. 2004;171:726–729. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000103500.21743.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wessells H. Ventral onlay graft techniques for urethroplasty. Urol. Clin. North Am. 2002;29:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Guazzoni G, Cavalcanti A. Bulbar urethroplasty using the dorsal approach: current techniques. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2003;29:155–161. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382003000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barbagli G, Selli C, Di Cello V, Mottola A. A one-stage dorsal free-graft urethroplasty for bulbar urethral strictures. BJU Int. 1996;78:929–932. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.23121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Andrich DE, Leach CJ, Mundy AR. The Barbagli procedure gives the best results for patch urethroplasty of the bulbar urethra. Br. J. Urol. 2001;88:385–389. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Lazzeri M, Turini D. Interim outcomes of dorsal skin graft bulbar urethroplasty. J. Urol. 2004;172:1365–1367. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000139727.70523.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Iselin CE, Webster GD. Dorsal onlay urethroplasty for urethral stricture repair. World J. Urol. 1998;16:181–185. doi: 10.1007/s003450050049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Rizzo M. Dorsal onlay graft urethroplasty using penile skin or buccal mucosa in adult bulbourethral strictures. J. Urol. 1998;160:1307–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Elliott SP, Metro MJ, McAninch JW. Long-term followup of the ventrally placed buccal mucosa onlay graft in bulbar urethral reconstruction. J. Urol. 2003;169:1754–1757. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000057800.61876.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Morey AF, McAninch JW. When and how to use buccal mucosal grafts in adult bulbar urethroplasty. Urology. 1996;48:194–198. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dubey D, et al. Substitution urethroplasty for anterior urethral strictures: a critical appraisal of various techniques. BJU Int. 2003;91:215–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.03064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Patterson JM, Chapple CR. Surgical techniques in substitution urethroplasty using buccal mucosa for the treatment of anterior urethral strictures. Eur. Urol. 2008;53:1162–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Barbagli G, Guazzoni G, Lazzeri M. One-stage bulbar urethroplasty: retrospective analysis of the results in 375 patients. Eur. Urol. 2008;53:828–833. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barbagli G, et al. Bulbar urethroplasty using buccal mucosa grafts placed on the ventral, dorsal or lateral surface of the urethra: are results affected by the surgical technique? J. Urol. 2005;174:955–958. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169422.46721.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Orandi A. One-stage urethroplasty. Br. J. Urol. 1968;40:717–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1968.tb11872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Quartey JK. One-stage penile/preputial cutaneous island flap urethroplasty for urethral stricture: a preliminary report. J. Urol. 1983;129:284–287. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Quartey JK. One-stage penile/preputial island flap urethroplasty for urethral stricture. J. Urol. 1985;134:474–475. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.McAninch JW. Reconstruction of extensive urethral strictures circular fasciocutaneous penile flap. J. Urol. 1993;149:488–491. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carney KJ, McAninch JW. Penile circular fasciocutaneous flaps to reconstruct complex anterior urethral strictures. Urol. Clin. North Am. 2002;29:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McAninch JW, Morey AF. Penile circular fasciocutaneous skin flap in 1-stage reconstruction of complex anterior urethral strictures. J. Urol. 1998;159:1209–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wessells H, McAninch JW. Circular penile fasciocutaneous flap reconstruction of urethral strictures: technical considerations and results in 40 patients. Tech. Urol. 1996;2:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dubey D, et al. Dorsal onlay buccal mucosa versus penile skin flap urethroplasty for anterior urethral strictures: results from a randomized prospective trial. J. Urol. 2007;178:2466–2469. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Erickson BA, Wysock JS, McVary KT, Gonzalez CM. Erectile function, sexual drive, and ejaculatory function after reconstructive surgery for anterior urethral stricture disease. BJU Int. 2007;99:607–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xie H, et al. Evaluation of erectile function after urethral reconstruction: a prospective study. Asian J. Androl. 2009;11:209–214. doi: 10.1038/aja.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sharma V, Kumar S, Mandal AK, Singh SK. A study on sexual function of men with anterior urethral stricture before and after treatment. Urol. Int. 2011;87:341–345. doi: 10.1159/000330268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Blaschko SD, Sanford MT, Cinman NM, McAninch JW, Breyer BN. De novo erectile dysfunction after anterior urethroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2013;112:655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Devine CJ, Franz JP, Horton CE. Evaluation and treatment of patients with failed hypospadias repair. J. Urol. 1978;119:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stecker JF, Horton CE, Devine CJ, McCraw JB. Hypospadias cripples. Urol. Clin. North Am. 1981;8:539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Barbagli G, Perovic S, Djinovic R, Sansalone S, Lazzeri M. Retrospective descriptive analysis of 1,176 patients with failed hypospadias repair. J. Urol. 2010;183:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Barbagli G, De Angelis M, Palminteri E, Lazzeri M. Failed hypospadias repair presenting in adults. Eur. Urol. 2006;49:887–895. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Myers JB, McAninch JW, Erickson BA, Breyer BN. Treatment of adults with complications from previous hypospadias surgery. J. Urol. 2012;188:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Perovic S, et al. Surgical challenge in patients who underwent failed hypospadias repair: is it time to change? Urol. Int. 2010;85:427–435. doi: 10.1159/000319856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Breyer BN, et al. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for long-term urethroplasty outcome. J. Urol. 2010;183:613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Barbagli G, De Angelis M, Romano G, Lazzeri M. Clinical outcome and quality of life assessment in patients treated with perineal urethrostomy for anterior urethral stricture disease. J. Urol. 2009;182:548–557. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Peterson AC, et al. Heroic measures may not always be justified in extensive urethral stricture due to lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans) Urology. 2004;64:565–568. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]