Abstract

Background

Homovanillic acid (HVA), 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) are the major monoamine metabolites in the central nervous system (CNS). Their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations, reflecting the monoamine turnover rates in CNS, are partially under genetic influence and have been associated with schizophrenia. We have hypothesized that CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations represent intermediate steps between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes implicated in monoaminergic pathways and psychosis.

Methods

We have searched for association between 119 SNPs in genes implicated in monoaminergic pathways [tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1), TPH2, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), DOPA decarboxylase (DDC), dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) and MAOB] and monoamine metabolite concentrations in CSF in 74 patients with psychotic disorder.

Results

There were 42 nominally significant associations between SNPs and CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations, which exceeded the expected number (20) of nominal associations given the total number of tests performed. The strongest association (p = 0.0004) was found between MAOB rs5905512, a SNP previously reported to be associated with schizophrenia in men, and MHPG concentrations in men with psychotic disorder. Further analyses in 111 healthy individuals revealed that 41 of the 42 nominal associations were restricted to patients with psychosis and were absent in healthy controls.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that altered monoamine turnover rates in CNS reflect intermediate steps in the associations between SNPs and psychosis.

Keywords: Psychosis, Schizophrenia, Psychiatric genetics, Cerebrospinal fluid, Homovanillic acid (HVA), 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG)

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a disorder affecting approximately 1% of the world’s population and with heritability up to 80% [1]. Many gene variations have been associated with the disorder, however the results have been ambiguous and difficult to replicate until recently, when genome wide analyses of several thousands of individuals have identified an increasing number of loci associated with schizophrenia [2]. Measurable biological markers may form intermediate steps between gene variations and the phenotype, i.e. the psychotic disorder, and associations between the biological measures and gene variants may be more robust than the associations between gene variants and the disorder itself.

Homovanillic acid (HVA), 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) are the major degradation products of the monoamines dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline, respectively. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) HVA, 5-HIAA and MHPG concentrations are considered to reflect the turnover rates of the monoamines in the central nervous system (CNS). Concentrations of HVA and 5-HIAA in ventricular, cisternal, and lumbar CSF show a craniocaudal gradient [3,4]. Postmortem human studies have shown that CSF HVA and 5-HIAA reflect brain HVA and 5-HIAA concentrations [5,6]. Correlations have been found between MHPG concentrations in CSF and MHPG concentrations in hypothalamus, temporal cortex, and pons in human autopsy cases [6]. Studies in human twins and other primates have shown that monoamine metabolite concentrations are partially under genetic influence [7,8].

Schizophrenia has been associated with monoamine metabolite concentrations, mainly HVA. HVA concentrations have been reported to be significantly lower in drug-free schizophrenic patients compared to controls [9,10]. Both quetiapine and olanzapine administration have been associated with a significant increase in CSF HVA [11,12].

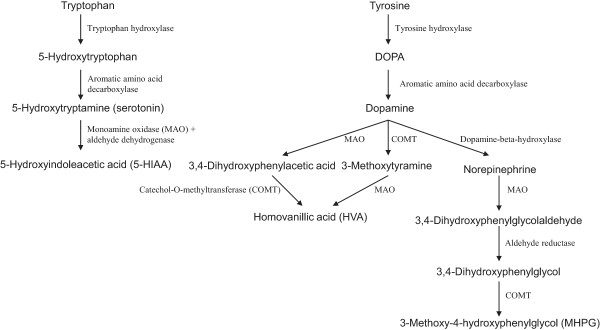

Tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) catalyses the conversion of tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan (Figure 1), which is the rate-limiting reaction in the biosynthesis of serotonin [13]. Two isoforms, TPH1 and TPH2, have been identified, encoded by two different genes, i.e. TPH1 and TPH2, located on chromosome 11p15.3–p14 and 12q21.1, respectively. Both TPH1 and TPH2 are expressed in the human brain and TPH1 may be preferentially expressed in the developing brain [14].

Figure 1.

Basic biochemical pathways of serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline.

Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) catalyzes the hydroxylation of L-tyrosine to 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylananine (Figure 1), which is the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of catecholamines [15]. The TH gene is located on chromosome 11p15.5.

DOPA decarboxylase (DDC), also known as aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, catalyzes the decarboxylation of both L-DOPA to dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptophan to serotonin [16]. Thus, this enzyme is involved in the dopamine and serotonin pathways and indirectly in the noradrenaline pathway (Figure 1). The DDC gene is located on chromosome 7p12.1 and consists of 15 exons spanning more than 75 kb [16].

Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH), localised in vesicles of noradrenergic and adrenergic cells [17], catalyses the conversion of dopamine to noradrenaline (Figure 1). DBH knockout mice lack noradrenaline and moreover show attenuated dopamine concentrations in various brain areas, due to interactions between noradrenergic and dopamine systems [18]. The DBH gene is located on chromosome 9q34.

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) catalyses the methyl conjugation and thus inactivation of the catecholamines and is the most important regulator of the prefrontal dopamine function [19]. This enzyme is not involved in the degradation of serotonin (Figure 1). The COMT gene is located on chromosome 22q11.2.

Monoamine oxidases are important enzymes for the degradation of various biogenic amines, including catecholamines and serotonin (Figure 1). There are two forms of the enzyme, monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) and monoamine oxidase B (MAOB), located throughout the brain in the outer membrane of mitochondria and encoded by two separate genes [20]. In humans, MAOA preferentially oxidizes serotonin and noradrenaline, whereas MAOB oxidizes dopamine [20]. The MAOA and MAOB genes are closely linked on the chromosome Xp11.23 and both include 15 exons with identical intron-exon organization, implying that they are derived from the same ancestral gene [21].

In the present study, we considered dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline turnover rates in CNS as probable intermediate steps between gene variants and schizophrenia. We hypothesized that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding the enzymes TPH1, TPH2, TH, DDC, DBH, COMT, MAOA and MAOB, all implicated in the basic biochemical pathways of the monoamines, affect the concentrations of HVA, 5-HIAA, and MHPG in the CSF of psychotic patients.

Methods

Subjects

Psychotic patients were initially recruited among inpatients at four psychiatric university clinics in Stockholm County between the years 1973 and 1987. After admittance patients were asked to participate in pharmacological and/or biological research projects as previously described [22]. Patients were usually observed for at least 48 hours without any antipsychotic medication before CSF was drawn by a lumbar puncture.

Three to 34 years after the first investigation, when CSF was obtained, subjects were asked to participate in genetic research and whole blood was drawn for genotyping. Subjects were also asked to participate in a structured interview [23] and to sign a request permitting the researchers to take part of his/her medical records. Available records were scrutinized by a researcher to obtain a life-time diagnosis according to DSM-III-R and DSM-IV. In 2010, 22 to 36 years after the initial CSF sampling, hospital discharge diagnoses were obtained from the Swedish psychiatric inpatient register (SPIR), which is a register based on the patient’s identification number, covering all inpatient hospitalizations in Sweden since 1973. For each hospitalization the diagnosis was recorded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 8th, 9th or 10th revisions. The majority of the participating individuals had experienced several hospitalizations, but each patient was given only one diagnosis, following a diagnostic hierarchy as previously described [24,25]. It was not possible to retrieve all medical records and several of the patients were not willing to participate in a diagnostic interview. Therefore, the final diagnoses were based on those obtained from SPIR.

Further analyses, investigating healthy individuals, were conducted for SNPs that were found to be associated with HVA, 5-HIAA or MHPG concentrations in psychotic patients, in order to evaluate whether the effects of the associated SNPs on the specific monoamine metabolites were restricted to patients with psychosis. Unrelated healthy Caucasians were investigated with lumbar puncture between the years 1973 and 1987 to participate in biological research. Eight to 20 years after the first investigation, when CSF was sampled, the subjects were interviewed to re-assess the absence of psychiatric morbidity as previously described [26]. At this interview whole blood was drawn for genotyping.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Karolinska University Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participating subjects.

CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations

CSF samples (12.5 ml) were drawn by lumbar puncture with the patients and controls in a sitting or recumbent position between 8 and 9 a.m, after at least 8 h of bed-rest and absence of food intake or smoking. 5-HIAA, HVA, and MHPG concentrations were measured by mass fragmentography with deuterium-labeled internal standards [27]. Back-length was defined as the distance between the external occipital protuberance and the point of needle insertion.

DNA analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood [28]. SNPs in TPH1 (n = 10), TPH2 (n = 21), TH (n = 10), DDC (n = 24), DBH (n = 25), COMT (n = 16), MAOA (n = 6) and MAOB (n = 7) were included. These SNPs were either candidate SNPs (n = 28) reported to be associated with schizophrenia, other mental disorders, enzyme function or monoamine metabolite concentrations, or tag-SNPs (n = 91), selected using HapMap to cover the genes of interest with an r2 threshold of 0.8. The genotyping was performed using the Illumina BeadStation 500GX and the 768-plex Illumina Golden Gate assay (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) [29].

Statistical analysis

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested using exact significance as implemented in STATA 12.1. Minor allele frequencies were measured using STATA 12.1. Normality of residuals was checked graphically with STATA 12.1. The associations between SNPs and CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations were tested with multiple linear regression (STATA 12.1), where concentration was modeled as a linear function of the allele count (of each SNP separately) and three to five covariates. In the case of psychotic patients, back-length, gender, age at lumbar puncture, diagnosis (i.e. schizophrenia spectrum psychosis or other psychosis) and use of antipsychotics were included as covariates. Antipsychotic treatment was considered as present if the patient had taken antipsychotics during a three-week period prior to the lumbar puncture. In the case of healthy controls, back-length, gender and age at lumbar puncture were included as covariates. MAOA and MAOB are located on chromosome X, and therefore the analyses of these genes were conducted separately for men and women.

In psychotic patients, we conducted 396 tests in total, as we have included 119 SNPs tested separately for the three different monoamine metabolites and moreover the X-linked MAOA and MAOB SNPs were tested separately in men and women. Adjustments for multiple testing were performed using Bonferroni correction taking into account a/the total number of tests conducted (α = 0.05/396 = 1.26x10−4) and b/ the total number of tests conducted, restricted to the 28 candidate SNPs (α = 0.05/90 = 5.56x10−4).

Results

Totally 74 patients (45 men and 29 women) were included in the present study. Their mean age ± standard deviation was 30.4 ± 7.2 years at lumbar puncture, whereas the mean age of disease onset was 27.6 ± 7.8.

A minority (n = 26) of the patients were treated with antipsychotics at the time of lumbar puncture, whereas the majority (n = 36) were free from antipsychotic medication since three weeks or longer. Sixty-four patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder (schizophrenia n = 60, schizoaffective disorder n = 4) and ten with other psychosis (psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS) n = 7, delusional disorder n = 1, bipolar disorder n = 1, alcohol induced psychotic disorder n = 1).

We conducted separate analyses, in order to evaluate how the SPIR-derived diagnoses conformed to other diagnostic tools used in the present study. Evaluations were made based on information originating from the medical records in 52 of the patients resulted in a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder in 98% of these individuals. Of 44 patients participating in a diagnostic interview [23], 91% displayed a psychotic disorder according to the SCID-I algorithm. Previous studies have also shown that the Swedish in-patient resister-based diagnoses of schizophrenia spectrum psychosis have a high validity, as 85% to 94% of these patients displayed these diagnoses when research psychiatrists made a diagnostic evaluation using information from medical records and a structured clinical interview [24].

In the 74 psychotic patients, 119 SNPs in eight genes encoding enzymes implicated in the monoamine metabolism were selected and genotyped. The minor allele frequency for the selected markers ranged from 2% to 49%. Departure from HWE (p-value < 0.05) was found in four of the 119 SNPs analyzed, i.e. DDC rs4947510, DDC rs921451, TPH2 rs1352250 and COMT rs165774. The residuals of the nominal associations were approximately normally distributed. In psychotic patients, the mean (S.D.) concentrations of the three monoamine metabolites were: HVA 178.6 (79.3) nmol/L; 5-HIAA 93.1 (34) nmol/L; MHPG 43.3 (9.3) nmol/L. Twelve, 12 and 18 of the investigated polymorphisms (Tables 1, 2 and 3) were found to be nominally associated with CSF HVA, 5-HIAA and MHPG concentrations, respectively.

Table 1.

SNPs nominally associated with CSF HVA concentrations in psychotic patients

| |

Patients with psychosis (n = 74; 45 men, 29 women) |

Healthy controls (n = 111; 63 men, 48 women) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HVA mean (S.D.) |

178.6 (79.3) nmol/l |

167.5 (68.4) nmol/l |

|||||

| Gene | SNP | MAF(%) | HWE | P | MAF(%) | HWE | P |

|

DDC |

rs11238133 |

36 |

0.211 |

0.004 |

41 |

1.000 |

0.757 |

|

DDC |

rs6951648 |

19 |

0.273 |

0.005 |

17 |

0.735 |

0.297 |

|

DDC |

rs10499696 |

11 |

0.186 |

0.009 |

9 |

0.594 |

0.681 |

|

DDC |

rs921451 |

42 |

0.018 |

0.011 |

43 |

0.564 |

0.661 |

|

DDC |

rs9942686 |

21 |

0.723 |

0.017 |

23 |

1.000 |

0.305 |

|

TH |

rs10770141 |

33 |

0.608 |

0.023 |

40 |

1.000 |

0.433 |

|

TPH1 |

rs211105 |

31 |

0.785 |

0.029 |

25 |

0.449 |

0.292 |

|

TH |

rs10840491 |

16 |

0.680 |

0.035 |

12 |

0.640 |

0.433 |

|

DDC |

rs6593011 |

15 |

0.652 |

0.038 |

13 |

0.208 |

0.959 |

|

COMT |

rs165774 |

32 |

0.003 |

0.043 |

30 |

0.258 |

0.650 |

|

TPH2 |

rs1872824 |

34 |

0.606 |

0.047 |

33 |

0.830 |

0.685 |

| TH | rs10840489 | 18 | 1.000 | 0.048 | 14 | 1.000 | 0.357 |

Minor allele frequencies (MAF), p-values of testing for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and p-values (P) from multiple linear regressions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) nominally associated with homovanillic acid (HVA) concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of psychotic patients and the corresponding association statistics among healthy controls.

Table 2.

SNPs nominally associated with CSF 5-HIAA concentrations in psychotic patients

| |

Patients with psychosis (n = 74; 45 men, 29 women) |

Healthy controls (n = 111; 63 men, 48 women) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5-HIAA mean (S.D.) |

93.1 (34) nmol/l |

90.8 (36.2) nmol/l |

|||||

| Gene | SNP | MAF (%) | HWE | P | MAF (%) | HWE | P |

|

MAOB(women) |

rs2311013 |

3 |

1.000 |

0.009 |

4 |

1.000 |

0.866 |

|

MAOB(women) |

rs1181252 |

3 |

1.000 |

0.009 |

4 |

1.000 |

0.053 |

|

DDC |

rs9942686 |

21 |

0.723 |

0.009 |

23 |

1.000 |

0.069 |

|

DDC |

rs11238133 |

36 |

0.211 |

0.012 |

41 |

1.000 |

0.516 |

|

DBH |

rs1611118 |

7 |

1.000 |

0.014 |

7 |

0.397 |

0.895 |

|

DDC |

rs11238131 |

30 |

0.784 |

0.019 |

32 |

0.826 |

0.829 |

|

MAOA (men) |

rs5906957 |

31 |

|

0.027 |

17 |

|

0.089 |

|

DDC |

rs11575535 |

4 |

1.000 |

0.035 |

4 |

1.000 |

0.302 |

|

TPH1 |

rs1799913 |

42 |

0.096 |

0.039 |

41 |

0.334 |

0.330 |

|

DBH |

rs6271 |

3 |

1.000 |

0.047 |

5 |

1.000 |

0.528 |

|

MAOA (men) |

rs4301558 |

36 |

|

0.048 |

20 |

|

0.123 |

| MAOA (men) | rs3027396 | 36 | 0.048 | 21 | 0.299 | ||

Minor allele frequencies (MAF), p-values of testing for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and p-values (P) from multiple linear regressions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) nominally associated with 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of psychotic patients and the corresponding association statistics among healthy controls. MAOA and MAOB are located on chromosome X and the analyses were therefore conducted separately for men and women.

Table 3.

SNPs nominally associated with CSF MHPG concentrations in psychotic patients

| |

Patients with psychosis (n = 74; 45 men, 29 women) |

Healthy controls (n = 111; 63 men, 48 women) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MHPG mean (S.D.) |

43.3 (9.3) nmol/l |

41.7 (8.1) nmol/l |

|||||

| Gene | SNP | MAF(%) | HWE | P | MAF (%) | HWE | P |

|

MAOB (men) |

rs5905512 |

47 |

|

0.0004 |

50 |

|

0.479 |

|

MAOB (men) |

rs1799836 |

38 |

|

0.0008 |

44 |

|

0.483 |

|

DDC |

rs11575535 |

4 |

1.000 |

0.005 |

4 |

1.000 |

0.126 |

|

TPH1 |

rs4537731 |

44 |

0.475 |

0.007 |

40 |

0.047 |

0.646 |

|

DDC |

rs6592961 |

28 |

0.400 |

0.008 |

29 |

0.104 |

0.855 |

|

TPH1 |

rs7933505 |

41 |

0.148 |

0.010 |

41 |

0.334 |

0.342 |

|

DDC |

rs7809758 |

40 |

0.811 |

0.013 |

38 |

0.159 |

0.956 |

|

TPH1 |

rs7122118 |

43 |

0.239 |

0.014 |

40 |

0.029 |

0.821 |

|

DBH |

rs6271 |

3 |

1.000 |

0.017 |

5 |

1.000 |

0.340 |

|

TPH1 |

rs1799913 |

42 |

0.096 |

0.017 |

41 |

0.334 |

0.342 |

|

TPH1 |

rs684302 |

42 |

0.232 |

0.017 |

41 |

0.171 |

0.397 |

|

DDC |

rs9942686 |

21 |

0.723 |

0.018 |

23 |

1.000 |

0.189 |

|

MAOB (men) |

rs6651806 |

24 |

|

0.021 |

32 |

|

0.328 |

|

DDC |

rs17133853 |

11 |

1.000 |

0.033 |

9 |

0.569 |

0.436 |

|

DBH |

rs1611115 |

21 |

1.000 |

0.035 |

14 |

1.000 |

0.791 |

|

DBH |

rs3025388 |

18 |

0.445 |

0.047 |

18 |

0.517 |

0.064 |

|

TPH1 |

rs12292915 |

44 |

0.161 |

0.047 |

43 |

0.052 |

0.066 |

| TPH1 | rs211105 | 31 | 0.785 | 0.049 | 25 | 0.449 | 0.033 |

Minor allele frequencies (MAF), p-values of testing for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and p-values (P) from multiple linear regressions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) nominally associated with 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of psychotic patients and the corresponding association statistics among healthy controls. MAOA and MAOB are located on chromosome X and the analyses were therefore conducted separately for men and women.

It may be argued that the genes selected for the present report are highly likely to influence monoamine metabolite concentrations in CSF, and giving strong a priori hypotheses, it has been suggested that correction for multiple testing is not necessary [30]. Therefore, we report all the nominal associations. Taking into account the total number of tests conducted, we also applied a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (α = 0.05/396 = 1.26 × 10−4) and none of the nominal associations were found to be statistically significant. As a less conservative alternative, we applied a Bonferroni correction taking into account the total number of tests conducted, restricted to the 28 candidate SNPs (α = 0.05/90 = 5.56x10−4). Using this correction, there was one significant result, i.e. the association between MAOB rs5905512 and CSF MHPG concentrations in psychotic men. In total, there were 42 nominal associations, which exceeded the expected number (20) of nominal associations given the 396 calculations performed [(119 SNPs + additional 13 calculations because of the gender-based calculations on the X-chromosome) × 3 monoamine metabolites)].

The associations (n = 42) between SNPs and monoamine metabolite concentrations which gave evidence for nominal significance in psychosis were tested in healthy individuals. There were 111 Caucasians (63 men and 48 women) included for that purpose. Their mean ages ± standard deviation were 28.4 ± 7.5 years at lumbar puncture. In the healthy Caucasians, the mean (S.D.) concentrations of the three monoamine metabolites were: HVA 167.5 (68.4) nmol/L; 5-HIAA 90.8 (36.2) nmol/L; MHPG 41.7 (8.1) nmol/L. The minor allele frequency for the selected markers ranged from 4% to 50%. Departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 0.05) was found in two of the SNPs analyzed (Table 3). The residuals were approximately normally distributed. With the exception of a nominal association between TPH1 rs211105 and MHPG concentrations, no associations were found (Table 3).

In the present study, mean CSF HVA and 5-HIAA concentrations were not found to be associated with antipsychotic treatment, whereas mean CSF MHPG concentration was significantly lower in patients who were prescribed antipsychotics compared to antipsychotic-free patients. We have included the use of antipsychotics as a covariate in all our analyses and moreover, our independent variables, i.e. the SNPs, are not expected to be associated with the presence or absence of antipsychotic treatment. Thus, the use of antipsychotics should not confound our analyses, even in the case of MHPG.

Discussion

In the present study, polymorphisms in genes coding for enzymes of importance for the catecholamine and serotonin metabolism were analyzed. There was an excess of nominally significant associations (42 observed versus 20 expected) among patients with psychotic disorder.

The Hardy-Weinberg principle is used in association studies to detect genotyping errors, inbreeding and population stratification [31]. Deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg proportions in psychotic individuals can provide evidence for association between SNPs and psychosis [31]. In the present study four SNPs showed departure from HWE (p < 0.05) in psychotic patients, i.e. DDC rs4947510, DDC rs921451, TPH2 rs1352250 and COMT rs165774. Departure from HWE in controls can indicate genotyping errors, inbreeding or population stratification [31]. Lack of HWE may also result as an effect of multiple testing. In the present study, two SNPs showed departure from HWE (p < 0.05) in healthy controls, i.e. TPH1 rs7122118 and TPH1 rs4537731. The results regarding these SNPs should be interpreted with caution.

TPH1 and TPH2

TPH1 gene variations have been associated with schizophrenia in several studies including meta-analyses (http://www.szgene.org). In the present study, one TPH1 SNP, i.e. rs1799913, was nominally associated with 5-HIAA concentrations. Rs1799913 has been associated with schizophrenia in single studies including a meta-analysis (http://www.szgene.org). We could therefore hypothesize that the previously reported association between TPH1 rs1799913 and schizophrenia may be mediated by serotonergic mechanisms and altered serotonin turnover rate in CNS.

One and seven TPH1 SNPs were associated with HVA and MHPG concentrations, respectively. Four of the polymorphisms associated with MHPG concentrations, including rs1799913, have previously been reported to be associated with schizophrenia (http://www.szgene.org).

One TPH2 SNP has been associated with the severity of positive psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia [32]. In the present study TPH2 rs1872824 was found to be associated with CSF HVA, whereas no association was found between TPH2 SNPs and CSF 5-HIAA or MHPG concentrations.

TH

TH gene variants have been associated with schizophrenia in 6 out of 19 studies. However, in a meta-analysis no association could be confirmed (http://www.szgene.org). Moreover, TH gene variation has been reported to be associated with CSF HVA and MHPG concentrations in healthy controls [33].

In the present study three TH SNPs, i.e. rs10770141, rs10840491 and rs10840489, were associated with HVA concentrations in patients with psychosis. Rs1077014, located upstream of TH in the proximal promoter, affects the transcriptional activity of the promoter and the catecholamine secretion in humans [34]. Rs1077014 may be associated with persistence, a typical personality trait in chronic fatigue syndrome patients [35] as well as with the personality trait of novelty seeking in healthy men [36]. To our knowledge rs10840491 and rs10840489 have not been ascribed any functionality or association with schizophrenia or other mental disorders.

DDC

No studies have shown significant associations between DDC SNPs and schizophrenia (http://www.szgene.org), whereas an association between DDC genotypes and age at disease onset has been found in men with schizophrenia [37]. Moreover, DDC deficiency has been reported to result in decreased HVA and 5-HIAA concentrations in CSF [38,39].

In the present study six, four and five DDC SNPs, all intronic, were nominally associated with CSF HVA, 5-HIAA and MHPG concentrations, respectively. Rs6592961 has been reported to be significantly associated with autism [40]. In the present study, this SNP was nominally associated with MHPG concentrations in psychotic patients.

DBH

In the present study, two DBH SNPs, i.e. rs1611118 and rs6271 and three DBH SNPs, i.e. rs6271, rs1611115, and rs3025388 were found to be nominally associated with 5-HIAA and MHPG concentrations, respectively, in psychotic patients. Rs1611115, located upstream of DBH, accounts for 31% to 52% of the variance of plasma DBH activity in different human populations [41], whereas rs6271, a nonsynonymous SNP located in exon 11, independently accounts for additional variance [42].

DBH SNPs have been associated with schizophrenia in 2/17 studies conducted (http://www.szgene.org). Rs1611115 has been significantly associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children [43], as well as with impulsiveness and aggressive hostility in adults [44]. Moreover, this SNP has been found to be associated with alcohol dependence in women [45]. Rs6271 was nominally associated with schizophrenia in both case–control and family based analyses in a north Indian schizophrenia cohort [46] and significantly associated with bipolar disorder in a Turkish population [47]. Rs1611118 and rs3025388 are intronic and to our knowledge, have not been ascribed any functionality or association with mental disorders.

COMT

COMT is a candidate gene for schizophrenia with many studies, including meta-analyses, reporting association between gene polymorphisms and the disorder (http://www.szgene.org). COMT gene variations have not shown associations with monoamine metabolite concentrations in healthy controls or in a mixed group of psychiatric patients [48,49]. In the present study, the intronic COMT rs165774 was nominally associated with HVA concentrations. Rs165774 showed departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in psychotic patients but not in healthy controls. Rs165774 has been reported to be significantly associated with schizophrenia [50] and alcohol dependence [51].

MAOA and MAOB

A minority of studies searching for association between MAOA or MAOB gene variation and schizophrenia reported a relationship (2/29 and 3/15, respectively) (http://www.szgene.org). MAOA polymorphisms have been associated with CSF HVA concentrations in patients with atypical depression [52], alcohol dependence and controls [53,54] as well as in a mixed group of psychiatric patients [49]. MAOA polymorphisms have also been associated with 5-HIAA in healthy men [55] and women [54].

In the present study, three MAOA SNPs were associated with 5-HIAA concentrations in psychotic men (Table 2), whereas three MAOB SNPs were associated with MHPG concentrations in psychotic men (Table 3) and two MAOB SNPs were associated with 5-HIAA concentrations in psychotic women (Table 2).

The associations between MAOB rs5905512 and MAOB rs1799836 and MHPG concentrations displayed the lowest p-values in the present study. MAOB rs5905512 was associated with MHPG concentrations in psychotic men (uncorrected p = 0.0004), which is statistically significant taking into account only the candidate SNPs tested. No association was found between rs5905512 and psychotic women, healthy men or healthy women. To our knowledge, two studies have searched for association between this SNP and schizophrenia (http://www.szgene.org) and our results are in accordance with one of these two studies [56], reporting significant association between rs5905512 and schizophrenia only in men, whereas the other study did not find any associations in either gender [57]. Moreover, rs5905512, located in intron 1, is a perfect proxy of a haplotype spanning from intron 1 to intron 3 and being subject to recent selection, in agreement with the ancestral susceptibility hypothesis of schizophrenia [56]. MAOB rs1799836 was also associated with MHPG concentrations in men with psychosis (uncorrected p = 0.001) in the present study. Rs1799836 is located in intron 13 and is associated with altered enzyme activity in vitro and in vivo [58,59]. Rs1799836 has been associated with schizophrenia in women [60]. The third MAOB SNP that was found to be associated with MHPG concentrations in psychotic men, i.e. rs6651806, has previously been reported to be associated with negative emotionality in healthy individuals [61]. To our knowledge, no functionality or association with mental disorders has been ascribed to the other MAOA (rs5906957, rs4301558, rs3027396) and MAOB (rs2311013, rs1181252) variants showing nominal association with monoamine metabolites in the present study.

Limitations

The present study has certain limitations. The relatively small number of participants, both patients and controls, in association with the large number of tests conducted, results in a limited power to detect possible associations between SNPs and CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations after correction for multiple testing. Moreover, the non-inclusion of tobacco use as a covariate may influence the results, especially with regard to HVA concentrations [62]. Finally, the associations found in the present study need replications in independent studies.

Conclusions

In psychotic patients, we found nominal associations between SNPs in genes encoding enzymes implicated in the monoamine pathways and the CNS monoamine turnover rates, as reflected by the CSF concentrations of HVA, 5-HIAA and MHPG. There were 42 nominal associations, which exceed the expected number (20) of nominal associations given the total number of tests performed. Forty-one out of these 42 suggestive associations were restricted to patients with psychosis and were absent in healthy controls. Some of the associated SNPs have been reported to be associated with schizophrenia. Moreover, one candidate MAOB SNP, previously reported to be associated with schizophrenia in men, was found to be significantly associated with MHPG concentrations in men with psychotic disorder, performing a correction for multiple testing for the number of candidate SNPs selected. Taken together, the present study supports the notion that altered monoamine turnover rates reflect intermediate steps in the associations between gene variations and psychosis.

Abbreviations

HVA: Homovanillic acid; 5-HIAA: 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; MHPG: 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; CNS: Central nervous system; TPH: Tryptophan hydroxylase; TH: Tyrosine hydroxylase; DDC: DOPA decarboxylase; DBH: Dopamine beta-hydroxylase; COMT: Catechol-O-methyltransferase; MAOA: Monoamine oxidase A; MAOB: Monoamine oxidase B; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; SPIR: Swedish psychiatric inpatient register; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DA contributed to the conception and design of the study, participated in subject assessment, subject characterization and the statistical analysis, managed the literature search and web-based database searches and drafted the article. ES performed the statistical analysis. TA was in charge of the genotyping procedures. GCS made a contribution to the conception and design of the study and to the acquisition of data. LT and IA contributed to the conception and design of the study. EGJ contributed to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition and the interpretation of data. All authors revised the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dimitrios Andreou, Email: dimitrios.andreou@sll.se.

Erik Söderman, Email: erik.soderman@glocalnet.net.

Tomas Axelsson, Email: tomas.axelsson@medsci.uu.se.

Göran C Sedvall, Email: goran.sedvall@gmail.com.

Lars Terenius, Email: Lars.Terenius@ki.se.

Ingrid Agartz, Email: ingrid.agartz@medisin.uio.no.

Erik G Jönsson, Email: erik.jonsson@ki.se.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and controls for their participation. This study was financed by the Swedish Research Council (K2007-62X-15077-04-1, K2008-62P-20597-01-3. K2010-62X-15078-07-2, K2012-61X-15078-09-3), the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and the Karolinska Institutet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and the HUBIN project. We thank Alexandra Tylec, Agneta Gunnar, Monica Hellberg, and Kjerstin Lind for technical assistance. Genotyping was performed by the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform in Uppsala, Sweden (http://www.genotyping.se) which is supported by Uppsala University, Uppsala University Hospital, Science for Life Laboratory - Uppsala and the Swedish Research Council.

References

- Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O’Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:537–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripke S, O’Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kahler AK, Akterin S, Bergen SE, Collins AL, Crowley JJ, Fromer M, Kim Y, Lee SH, Magnusson PK, Sanchez N, Stahl EA, Williams S, Wray NR, Xia K, Bettella F, Borglum AD, Bulik-Sullivan BK, Cormican P, Craddock N, de Leeuw C, Durmishi N, Gill M, Golimbet V, Hamshere ML, Holmans P, Hougaard DM. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1150–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moir AT, Ashcroft GW, Crawford TB, Eccleston D, Guldberg HC. Cerebral metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid as a biochemical approach to the brain. Brain. 1970;93:357–368. doi: 10.1093/brain/93.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin C, Siwers B, Bertilsson L. Site of lumbar puncture influences levels of monoamine metabolites. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1445. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290120075017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Traskman-Bendz L, Dorovini-Zis K. Correlations between aminergic metabolites simultaneously obtained from human CSF and brain. Life Sci. 1985;37:1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester P, Bergstrom U, Eriksson A, Gezelius C, Hardy J, Winblad B. Ventricular cerebrospinal fluid monoamine transmitter and metabolite concentrations reflect human brain neurochemistry in autopsy cases. J Neurochem. 1990;54:1148–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenstierna G, Edman G, Iselius L, Oreland L, Ross SB, Sedvall G. Concentrations of monoamine metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid of twins and unrelated individuals - a genetic study. J Psychiatr Res. 1986;20:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(86)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Martin LJ, Comuzzie AG, Mann JJ, Manuck SB, Leland M, Kaplan JR. Genetics of monoamine metabolites in baboons: overlapping sets of genes influence levels of 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid, 3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenylglycol, and homovanillic acid. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerkenstedt L, Edman G, Hagenfeldt L, Sedvall G, Wiesel F-A. Plasma amino acids in relation to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites in schizophrenic patients and healthy controls. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:276–282. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieselgren IM, Lindstrom LH. CSF levels of HVA and 5-HIAA in drug-free schizophrenic patients and healthy controls: a prospective study focused on their predictive value for outcome in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1998;81:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikisch G, Baumann P, Wiedemann G, Kiessling B, Weisser H, Hertel A, Yoshitake T, Kehr J, Mathe AA. Quetiapine and norquetiapine in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients treated with quetiapine: correlations to clinical outcome and HVA, 5-HIAA, and MHPG in CSF. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:496–503. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181f2288e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers FE, Gispen-de Wied CC, Westenberg HG, Kahn RS. The effect of olanzapine treatment on monoamine metabolite concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:468–475. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JR, Melcer I. The enzymic oxidation of tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan in the biosynthesis of serotonin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961;132:265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Sugawara Y, Sawabe K, Ohashi A, Tsurui H, Xiu Y, Ohtsuji M, Lin QS, Nishimura H, Hasegawa H, Hirose S. Late developmental stage-specific role of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 in brain serotonin levels. J Neurosci. 2006;26:530–534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1835-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatmark T, Stevens RC. Structural insight into the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases and their disease-related mutant forms. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2137–2160. doi: 10.1021/cr980450y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi-Ichinose C, Ichinose H, Takahashi E, Hori T, Nagatsu T. Molecular cloning of genomic DNA and chromosomal assignment of the gene for human aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, the enzyme for catecholamine and serotonin biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2229–2238. doi: 10.1021/bi00123a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper CM, O’Connor DT, Westlund KN. Immunocytochemical localization of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in neurons of the human brain stem. Neuroscience. 1987;23:981–989. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schank JR, Ventura R, Puglisi-Allegra S, Alcaro A, Cole CD, Liles LC, Seeman P, Weinshenker D. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase knockout mice have alterations in dopamine signaling and are hypersensitive to cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2221–2230. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagud M, Muck-Seler D, Mihaljevic-Peles A, Vuksan-Cusa B, Zivkovic M, Jakovljevic M, Pivac N. Catechol-O-methyl transferase and schizophrenia. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:270–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JC, Chen K, Ridd MJ. Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:197–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsby J, Chen K, Wang LJ, Lan NC, Shih JC. Human monoamine oxidase A and B genes exhibit identical exon-intron organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:3637–3641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlborg A, Jokinen J, Nordström A-L, Jönsson EG, Nordström P. CSF 5-HIAA, attempted suicide and suicide risk in schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2009;112:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R - Patient Version (SCID-P) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Vares M, Ekholm A, Sedvall GC, Hall H, Jönsson EG. Characterisation of patients with schizophrenia and related psychosis: evaluation of different diagnostic procedures. Psychopathology. 2006;39:286–295. doi: 10.1159/000095733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm B, Ekholm A, Adolfsson R, Vares M, Ösby U, Sedvall GC, Jönsson EG. Evaluation of diagnostic procedures in Swedish patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59:457–464. doi: 10.1080/08039480500360906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson EG, Bah J, Melke J, Abou Jamra R, Schumacher J, Westberg L, Ivo R, Cichon S, Propping P, Nothen MM, Eriksson E, Sedvall GC. Monoamine related functional gene variants and relationships to monoamine metabolite concentrations in CSF of healthy volunteers. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn C-G, Sandgärde B, Wiesel F-A, Sedvall G. Simultaneous determination of the three major monoamine metabolites in brain tissue and body fluids by a mass fragmentographic method. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1976;48:147–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00423253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijer T, Neiman J, Rydberg U, Gyllander A, Jönsson E, Sedvall G, Valverius P, Terenius L. Dopamine D2 receptor gene polymorphisms in Scandinavian chronic alcoholics. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;244:26–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02279808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan JB, Oliphant A, Shen R, Kermani BG, Garcia F, Gunderson KL, Hansen M, Steemers F, Butler SL, Deloukas P, Galver L, Hunt S, McBride C, Bibikova M, Rubano T, Chen J, Wickham E, Doucet D, Chang W, Campbell D, Zhang B, Kruglyak S, Bentley D, Haas J, Rigault P, Zhou L, Stuelpnagel J, Chee MS. Highly parallel SNP genotyping. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2003;68:69–78. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2003.68.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ. Six persistent research misconceptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1060–1064. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2755-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Shete S. Testing departure from Hardy-Weinberg proportions. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;850:77–102. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-555-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Li Z, Shao Y, Xie B, Du Y, Fang Y, Yu S. Association study of tryptophan hydroxylase-2 gene in schizophrenia and its clinical features in Chinese Han population. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43:406–411. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson E, Sedvall G, Brené S, Gustavsson JP, Geijer T, Terenius L, Crocq M-A, Lannfelt L, Tylec A, Sokoloff P, Schwartz JC, Wiesel F-A. Dopamine-related genes and their relationships to monoamine metabolites in CSF. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao F, Zhang K, Zhang L, Rana BK, Wessel J, Fung MM, Rodriguez-Flores JL, Taupenot L, Ziegler MG, O’Connor DT. Human tyrosine hydroxylase natural allelic variation: influence on autonomic function and hypertension. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:1391–1394. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Horiguchi M, Yamaguti K, Nakatomi Y, Kuratsune H, Ichinose H, Watanabe Y. Association of monoamine-synthesizing genes with the depression tendency and personality in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Life Sci. 2013;92:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Shibuya N, Kamata M, Matsumoto Y, Goto K, Otani K. Association study between a functional polymorphism of tyrosine hydroxylase gene promoter and personality traits in healthy subjects. Behav Brain Res. 2010;208:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Børglum AD, Hampson M, Kjeldsen TE, Muir W, Murray V, Ewald H, Mors O, Blackwood D, Kruse TA. Dopa decarboxylase genotypes may influence age at onset of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:712–717. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland K, Clayton PT. Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: diagnostic methodology. Clin Chem. 1992;38:2405–2410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam C, Hyland K, Wevers R, Sharma R, Wagner L, Stock GJ, Heitmann F, Hoffmann GF. Clinical and laboratory findings in twins with neonatal epileptic encephalopathy mimicking aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:113–117. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma C, Hervas A, Balmana N, Salgado M, Maristany M, Vilella E, Aguilera F, Orejuela C, Cusco I, Gallastegui F, Perez-Jurado LA, Caballero-Andaluz R, Diego-Otero YD, Guzman-Alvarez G, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Ribases M, Bayes M, Cormand B. Neurotransmitter systems and neurotrophic factors in autism: association study of 37 genes suggests involvement of DDC. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;14:516–527. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.602719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabetian CP, Anderson GM, Buxbaum SG, Elston RC, Ichinose H, Nagatsu T, Kim KS, Kim CH, Malison RT, Gelernter J, Cubells JF. A quantitative-trait analysis of human plasma-dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity: Evidence for a major functional polymorphism at the DBH locus. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:515–522. doi: 10.1086/318198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Anderson GM, Zabetian CP, Kohnke MD, Cubells JF. Haplotype-controlled analysis of the association of a non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism at DBH (+1603C – >T) with plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;139B:88–90. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HJ, Lim MH. Association between dopamine Beta-hydroxylase gene polymorphisms and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in korean children. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17:529–534. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2013.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess C, Reif A, Strobel A, Boreatti-Hummer A, Heine M, Lesch KP, Jacob CP. A functional dopamine-beta-hydroxylase gene promoter polymorphism is associated with impulsive personality styles, but not with affective disorders. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:121–130. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Wurst FM, Ridinger M, Rujescu D, Fehr C, Koller G, Bondy B, Wodarz N, Soyka M, Zill P. Association of functional DBH genetic variants with alcohol dependence risk and related depression and suicide attempt phenotypes: Results from a large multicenter association study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukshal P, Kodavali VC, Srivastava V, Wood J, McClain L, Bhatia T, Bhagwat AM, Deshpande SN, Nimgaonkar VL, Thelma BK. Dopaminergic gene polymorphisms and cognitive function in a north Indian schizophrenia cohort. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1615–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates O, Celikel FC, Taycan SE, Sezer S, Karakus N. Association between 1603C > T polymorphism of DBH gene and bipolar disorder in a Turkish population. Gene. 2013;519:356–359. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson EG, Goldman D, Spurlock G, Gustavsson JP, Nielsen DA, Linnoila M, Owen MJ, Sedvall GC. Tryptophan hydroxylase and catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms: relationships to monoamine metabolite concentrations in CSF of healthy volunteers. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247:297–302. doi: 10.1007/BF02922258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G, Huang YY, Harkavy-Friedman JM, Oquendo MA, Ellis SP, Mann JJ. Relationship of MAO-A promoter (u-VNTR) and COMT (V158M) gene polymorphisms to CSF monoamine metabolites levels in a psychiatric sample of caucasians: A preliminary report. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;132B:100–103. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisey J, Swagell CD, Hughes IP, Lawford BR, Young RM, Morris CP. HapMap tag-SNP analysis confirms a role for COMT in schizophrenia risk and reveals a novel association. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisey J, Swagell CD, Hughes IP, Lawford BR, Young RM, Morris CP. A novel SNP in COMT is associated with alcohol dependence but not opiate or nicotine dependence: a case control study. Behav Brain Funct. 2011;7:51. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aklillu E, Karlsson S, Zachrisson OO, Ozdemir V, Agren H. Association of MAOA gene functional promoter polymorphism with CSF dopamine turnover and atypical depression. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19:267–275. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328328d4d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducci F, Newman TK, Funt S, Brown GL, Virkkunen M, Goldman D. A functional polymorphism in the MAOA gene promoter (MAOA-LPR) predicts central dopamine function and body mass index. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:858–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson EG, Norton N, Gustavsson JP, Oreland L, Owen MJ, Sedvall GC. A promoter polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene and its relationships to monoamine metabolite concentrations in CSF of healthy volunteers. J Psychiatr Res. 2000;34:239–244. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RB, Marchuk DA, Gadde KM, Barefoot JC, Grichnik K, Helms MJ, Kuhn CM, Lewis JG, Schanberg SM, Stafford-Smith M, Suarez EC, Clary GL, Svenson IK, Siegler IC. Serotonin-related gene polymorphisms and central nervous system serotonin function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:533–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera N, Sanjuan J, Molto MD, Carracedo A, Costas J. Recent adaptive selection at MAOB and ancestral susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:369–374. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas S, Bernardo M, Parellada E, Garcia-Rizo C, Gasso P, Alvarez S, Lafuente A. ARVCF single marker and haplotypic association with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:1064–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mallen P, Kelada SN, Costa LG, Checkoway H. Characterization of the in vitro transcriptional activity of polymorphic alleles of the human monoamine oxidase-B gene. Neurosci Lett. 2005;383:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balciuniene J, Emilsson L, Oreland L, Pettersson U, Jazin E. Investigation of the functional effect of monoamine oxidase polymorphisms in human brain. Hum Genet. 2002;110:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0652-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasso P, Bernardo M, Mas S, Crescenti A, Garcia C, Parellada E, Lafuente A. Association of A/G polymorphism in intron 13 of the monoamine oxidase B gene with schizophrenia in a Spanish population. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;58:65–70. doi: 10.1159/000159774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugos AM, Palmer AA, de Wit H. Negative emotionality: monoamine oxidase B gene variants modulate personality traits in healthy humans. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:1323–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0281-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geracioti TD Jr, West SA, Baker DG, Hill KK, Ekhator NN, Wortman MD, Keck PE Jr, Norman AB. Low CSF concentration of a dopamine metabolite in tobacco smokers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:130–132. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]