Abstract

An emerging aspect of redox signaling is the pathway mediated by electrophilic byproducts, such as nitrated cyclic nucleotide (for example, 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-nitro-cGMP)) and nitro or keto derivatives of unsaturated fatty acids, generated via reactions of inflammation-related enzymes, reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide and secondary products. Here we report that enzymatically generated hydrogen sulfide anion (HS−) regulates the metabolism and signaling actions of various electrophiles. HS− reacts with electrophiles, best represented by 8-nitro-cGMP, via direct sulfhydration and modulates cellular redox signaling. The relevance of this reaction is reinforced by the significant 8-nitro-cGMP formation in mouse cardiac tissue after myocardial infarction that is modulated by alterations in HS− biosynthesis. Cardiac HS−, in turn, suppresses electrophile-mediated H-Ras activation and cardiac cell senescence, contributing to the beneficial effects of HS− on myocardial infarction–associated heart failure. Thus, this study reveals HS−-induced electrophile sulfhydration as a unique mechanism for regulating electrophile-mediated redox signaling.

Endogenous formation of the gaseous signaling mediator hydrogen sulfide (H2S) has been demonstrated in mammalian cells and tissues1,2, but its chemical nature and physiological functions remain poorly defined. Although reactive oxygen species (ROS) are typically viewed as toxic mediators of oxidative stress in aerobic organisms3, ROS are now appreciated to mediate signal transduction events during both basal metabolism and inflammatory responses4–6. Electrophilic products can be formed via enzymatic oxidation reactions or reactions of ROS, nitric oxide and their secondary products7–12. Biological electrophiles can lend additional specificity to redox-dependent signal transduction via the nucleophilic substitution or Michael addition of electrophiles with cysteine sulfhydryls of various sensor or effector proteins to form their S-alkylation or S-arylation adducts7,8. Redox signal transduction reactions include those mediated by electrophilic byproducts of redox reactions4,7, such as the electrophilic nucleotide 8-nitro-cGMP and multiple unsaturated fatty acid–derived oxo and nitro derivatives7– 12. Aerobic cells rely on various oxidant-scavenging enzyme systems and low-molecular-weight scavengers to defend against the vicissitudes of oxidative stress3. Other than reactions with glutathione (GSH), however, the reactions modulating potential signaling and pathogenic actions of electrophilic species remain undefined.

Herein, we demonstrate that HS−, rather than H2S, regulates the metabolism and signaling functions of endogenous electrophiles. The nucleophilic properties of HS− support a reaction with various electrophiles in cells via direct chemical sulfhydration (that is, electrophile sulfhydration). In vivo treatment of mice with HS− ameliorated chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction, and improvement was partially a consequence of the sulfhydration of 8-nitro-cGMP generated in excess in cardiac tissues after myocardial infarction. These potent beneficial pharmacological effects stemmed from the sulfhydration of electrophilic 8-nitro-cGMP, which resulted in the suppression of a cellular senescence response induced by electrophile- dependent H-Ras activation in cardiomyocytes and cardiac tissues. This H-Ras activation involved downstream signaling pathways, including the Raf-extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) pathways, which led to activation of p53 and retinoblastoma protein (Rb). These data support that HS−-induced sulfhydration of electrophile species is a mechanism for terminating electrophile-mediated signaling and suggest a new therapeutic strategy for treating oxidative inflammation-related diseases3,5–9.

RESULTS

HS−-producing enzymes involved in electrophile metabolism

To clarify the mechanisms regulating the metabolism and signaling actions of various electrophiles, we performed RNA interference (RNAi) screening that focused on cysteine metabolism and its redox-related metabolic pathways (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Results, Supplementary Table 1). This method was based on the modulation of protein S-guanylation in A549 (human lung epithelial adenocarcinoma) and other cultured cells after treatment with small interfering RNA (siRNA) for various genes (Fig. 1a,b). This RNAi screening revealed the substantial impact of endogenous HS− generation on 8-nitro-cGMP metabolism. In particular, two key enzymes of HS−-H2S biosynthesis, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) (Supplementary Fig. 1a), had a significant impact on the metabolism of cellular 8-nitro-cGMP in cultured mammalian cell lines, including A549, HepG2 (human hepatoblastoma) and C6 cells (rat glioblastoma) (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 for each assay; Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 1). Protein S-guanylation caused by exogenously administered 8-nitro-cGMP was markedly augmented after knockdown of CBS or CSE in A549, HepG2 and C6 cells (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 1b–d). Moreover, the basal extent of protein S-guanylation induced by endogenous 8-nitro-cGMP generation was also elevated by CBS or CSE knockdown (Fig. 1a,b). These data reveal that the HS−-generating enzymes (CBS and CSE) are critical for 8-nitro-cGMP metabolism. This metabolism was linked with the release of nitrite (NO2 −) via a mechanism dependent on CBS and CSE (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), supporting a reliance on the nucleophilic qualities of H2S (pKa 6.7), especially anionic HS−, which predominates in neutral biological solutions (Fig. 1c)13. The extent of NO2 − generation was linked with 8-nitro-cGMP degradation in cells, which in turn depended on HS− formed from CBS or CSE (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). These findings support that enzymatically generated HS− mediates 8-nitro-cGMP metabolism.

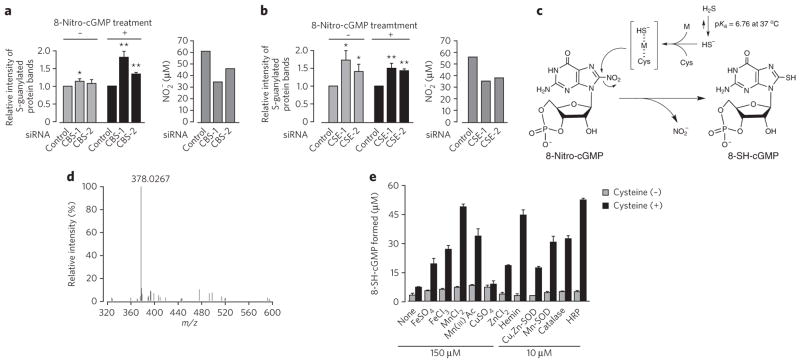

Figure 1. Regulation of 8-nitro-cGMP–induced protein S-guanylation by HS−-producing enzymes via sulfhydration of 8-nitro-cGMP by HS−.

(a,b) Enhancement of protein S-guanylation by knockdown of CBS (a) and CSE (b) in A549 cells treated or untreated with 8-nitro-cGMP (200 μM). In a and b, quantitative data (via densitometric analysis) of S-guanylation western blots are shown at left, and NO2 − release from 8-nitro-cGMP with A549 cells in culture with and without knockdown of CBS or CSE is shown at right. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus control. Original western blot images are shown in Supplementary Figure 1b. (c) Possible reaction mechanisms in HS−-dependent sulfhydration of 8-nitro-cGMP. Transition metals (M) and cysteine thiolate anion (Cys-S−) may participate in sulfhydration by stabilizing the HS− anion. (d) Mass spectrum of the peak identified as 8-SH-cGMP formed in the reaction of 8-nitro-cGMP with NaHS. (e) Effects of cysteine and metals on HS−-mediated sulfhydration of 8-nitro-cGMP. The reaction of 8-nitro-cGMP (100 μM) with NaHS (1 mM) was carried out in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 100 μM DTPA in the absence or presence of additives including cysteine (100 μM), metals (150 μM FeSO 4, FeCl3, MnCl2, CuSO 4 or ZnCl2) and metal-containing compounds or proteins (10 μM hemin, Cu,Zn-SO D, Mn-SO D, catalase or HRP) at 37 °C for 5 h. Data represent mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

Denitration and sulfhydration of 8-nitro-cGMP by HS−

To clarify how HS−, rather than gaseous H2S, could undergo an SH-addition reaction (that is, electrophile sulfhydration), we analyzed cell-free reactions of 8-nitro-cGMP with sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS), used as an HS− donor, via reverse-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) and LC/MS. The electrophilic nitro moiety underwent nucleophilic substitution with HS− to yield the new product, 8-SH-cGMP (Fig. 1c,d and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Transition metal ions such as iron and manganese added to the reaction mixture greatly increased 8-SH-cGMP formation, whereas copper addition showed no or minimal effects (Fig. 1e). Metal complexes and metalloproteins, such as hemin, Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn-SOD), Mn-SOD, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and catalase, also promoted sulfhydration reactions, with HRP having the greatest effect. This observation supports a potent catalytic activity of endogenous transition metals—and metalloproteins—in sulfhydration. Sulfhydryls act as ligands for metal ions; thus, HS−-containing metal complexes may acquire added stability and catalyze sulfhydration (Fig. 1c). H2S can be oxidized to sulfur oxides such as thiosulfate (S2O32−), sulfite (SO32−) and sulfate (SO42−) under aerobic conditions or via cell metabolism2,14. These sulfur oxides, which may be formed via oxidation of H2S/HS−, did not react with 8-nitro-cGMP to induce sulfhydration (Supplementary Fig. 3b), confirming the specificity of HS− in electrophile sulfhydration. We observed clear pH-dependent, HS−-induced sulfhydration of 8-nitro-cGMP (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The efficacy of 8-SH-cGMP formation increased linearly as the pH increased from 5 to 8, which correlated well with the reported pH-dependent equilibrium of H2S/HS− (ref. 13). The electrophile sulfhydration potential of HS− is superior to that of GSH-dependent nucleophilic modification of 8-nitro-cGMP within a physiologically relevant pH range of the reaction mixture containing cysteine and HRP (Supplementary Fig. 3c). This finding also indicates a substantial contribution of HS− to electrophile metabolism via sulfhydration in comparison with electrophile metabolism with GSH and other sulfhydryl compounds such as cysteine and homocysteine (HCys) with a relatively high pKa (>8).

HS−-mediated sulfhydration with diverse electrophiles

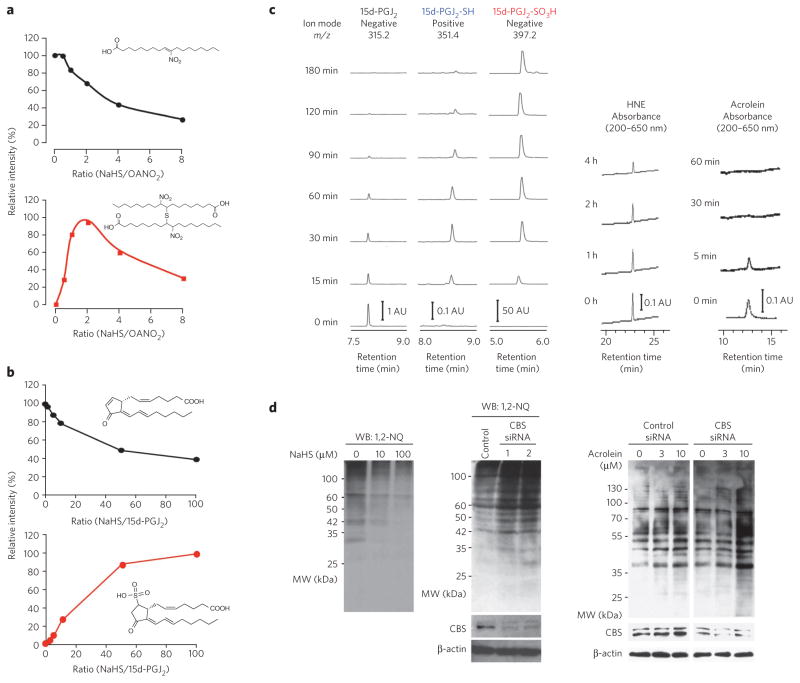

Sulfhydration by HS− occurred with a broad array of biological electrophiles that have either cell signaling or toxicological properties (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 4). These electrophiles include the cyclopentenone 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), acrolein and fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives. LC/MS indicated that the common primary reaction with these electrophilic lipid derivatives was nucleophilic addition or substitution of HS− at the electrophilic carbon (Figs. 2 and 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Another reaction was the Michael addition of HS− to electrophiles such as 1,2-naphthoquinone (1,2-NQ) and other related quinones (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). The reaction of 1,2-NQ with HS− yielded 1,2-NQ-SH and (1,2-NQ)2S.

Figure 2. Electrophile sulfhydration by HS−.

(a) LC/MS analysis for the OANO2 and HS− reaction. OANO2 (100 μM) was reacted with different concentrations of NaHS in 200 mM potassium phosphate buffer at 25 °C for 1 h. (b) LC/MS for identification of 15d-PGJ2-SO 3H as a product of the reaction of 15d-PGJ2 (1 μM) and HS− in 100 mM phosphate buffer at 37 °C for 2 h. (c) Time-dependent effects of HS− on stability of various electrophiles. Left, single-ion recordings of 15d-PGJ2, 15d-PGJ2-SH and 15d-PGJ2-SO3H in the same reaction as in b with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) and NaHS (1 mM). The MS spectrum of each PGJ2 derivative is shown in Supplementary Figure 4c. Right, HNE and acrolein determined by RP-HPLC analyses. HNE (10 μM) or acrolein (10 μM) was incubated with NaHS (200 μM for HNE; 100 μM for acrolein) in 100 mM phosphate buffer at 37 °C. AU, arbitrary unit. (d) Effects of HS− on protein electrophile adductions in A549 cells. Cells were pretreated with NaHS or were untreated for 12 h, followed by treatment with 1,2-NQ (10 μM) for 1 h. Total cellular proteins were subjected to western blotting (WB). Cells were transfected with control siRNA or CBS siRNA and were then exposed to 1,2-NQ (10 μM) for 1 h or to acrolein (3 μM or 10 μM) for 30 min. Western blots for 1,2-NQ and acrolein protein adducts formed in A549 cells with CBS knockdown or untreated cells (middle and right). Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Figure 17. MW, molecular weight.

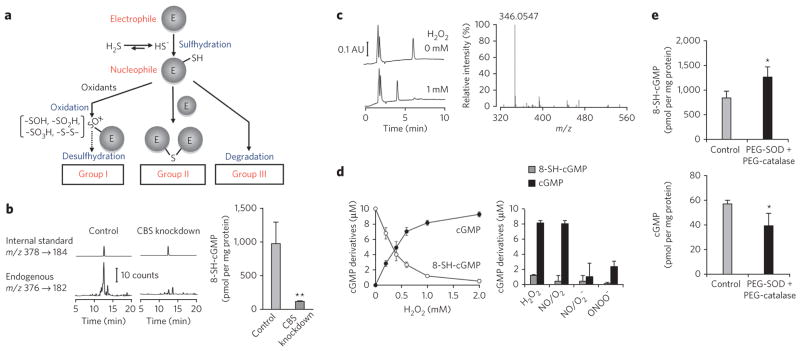

Figure 3. Cellular formation of 8-SH-cGMP and its metabolic fate.

(a) Metabolic fate of electrophiles after reaction with HS−. Details of the classification are shown in Supplementary Figure 6. (b) Formation of 8-SH-cGMP and its suppression by CBS knockdown in 8-nitro-cGMP–treated A549 cells. 8-SH-cGMP formation was determined via LC-ESI-MS/MS (8-[34SH]-cGMP was used as an internal standard). Data represent mean ± s.d. (n = 3). **P < 0.01. (c) Oxidative desulfhydration of 8-SH-cGMP by H2O2 to form cGMP. Left, the reaction of 8-SH-cGMP (10 μM) with H2O2 (1 mM) led to the disappearance of 8-SH-cGMP (elution time, 6 min) and appearance of a new peak (elution time, 4 min). Right, LC/MS identified cGMP as a major product in the reaction of 8-SH-cGMP with H2O2. AU, arbitrary unit. (d) Oxidative desulfhydration of 8-SH-cGMP by H2O2 and RNOS. 8-SH-cGMP (10 μM) was reacted with various concentrations of H2O2 (left) and with H2O2 and RNOS (1 mM each) (right). NO/O2: NO under aerobic conditions, producing nitrogen oxides; NO/O2 −: simultaneous generation of NO and O2 − by 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) to form ONOO− in situ; ONOO−: synthetic ONOO−. Data represent mean ± s.d. (n = 3). (e) Stability of 8-SH-cGMP formed from 8-nitro-cGMP in A549 cells enhanced by antioxidant enzymes. A549 cells were treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (200 μM) in the absence and presence of antioxidant PEG-SO D (100 U ml−1) and PEG-catalase (200 U ml−1) for 6 h. LC-ESI-MS/MS was used to determine 8-SH-cGMP and cGMP formation. Data represent mean ± s.d. (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

Reactions occurring after sulfhydration varied with individual electrophiles. In many cases, secondary reactions with parent electrophiles yielded bis-thio derivatives, as was observed with nitrooleic acid (OANO2), which underwent S-bridged dimerization (Figs. 2a and 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4a,b), and with 1,2-NQ, 1,4-NQ and tert-butylbenzoquinone (Supplementary Fig. 5). One exception was 8-nitro-cGMP; RP-HPLC and LC/MS detected only the sulfhydrated product, 8-SH-cGMP. Similarly to 8-nitro-cGMP, 15d-PGJ2 was readily sulfhydrated to form a transient unstable SH adduct that rapidly converted to sulfonated 15d-PGJ2-SO3H, the sole final product (Figs. 2b,c and 3a and Supplementary Figs. 4c and 6). This interpretation is supported by the fate of 8-SH-cGMP treated with various oxidants, specifically treatment resulting in a rapid oxidative desulfhydration as described below (Fig. 3). Certain lipid-derived endogenous electrophiles, such as HNE and acrolein, degraded rapidly after reacting with HS−, without forming any appreciable products detected by RP-HPLC (Fig. 2c). Michael adducts of HNE with cysteine and histidine, HNE-His and HNE-Cys, were resistant to the same HS− reaction, suggesting that both HNE and acrolein undergo efficient HS−-induced decomposition in a manner dependent on their strong electrophilicity (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Consistent with these findings, the Michael adduction of cellular proteins by 1,2-NQ or acrolein was markedly enhanced when CBS was knocked down in A549 cells (Fig. 2d). These data support the regulation of not only electrophilic S-guanylation but also S-alkylation or S-arylation of cellular proteins by HS− reactions with the parent electrophile. The relative reactivities of electrophiles with HS− was estimated by the rate of consumption of electrophiles in the presence of HS−. Acrolein showed the highest reactivity with HS−, with relative reactivities decreasing in the order OANO2 > HNE > 15d-PGJ2 > 8-nitro-cGMP, whereas the reactivities of these electrophiles with GSH were similar4,7,8.

Metabolism of sulfhydrated electrophiles and 8-SH-cGMP

The metabolic fate of these sulfhydrated derivatives of electrophiles allowed us to sort the electrophiles into three groups (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 6). In group 1, because the SH derivative was so stable, no other reaction occurred except for oxidative modifications of SH by ROS and other reactive species. Group 2 involved relatively stable bis product formation. Group 3 may include other highly reactive electrophiles, such as HNE and acrolein, for which additional metabolism and secondary chemical reactions followed SH addition.

Endogenous HS−-dependent sulfhydration occurred in A549, HepG2 and C6 cells, as evidenced by 8-SH-cGMP formation from exogenously added 8-nitro-cGMP (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 7). CBS knockdown markedly inhibited 8-SH-cGMP formation in A549 cells, a finding confirming CBS as a major source of endogenous HS−. Because 8-SH-cGMP contains sulfhydryls, it is presumably oxygen labile or susceptible to further oxidization. To test this possibility, we treated 8-SH-cGMP with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and reactive nitrogen oxide species (RNOS) including nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−), which stem from the concurrent generation of NO and superoxide (Fig. 3c,d). Notably, the sole detectable product of this reaction was cyclic GMP (cGMP) rather than oxidized derivatives of 8-SH-cGMP, such as 8-sulfenyl-, 8-sulfinyl- and 8-sulfonyl-cGMP or 8-OH-cGMP (Fig. 3c,d), thus representing what is to our knowledge the first identification of oxidant-induced desulfhydration of SH-containing compounds. Remarkably, the oxidant-labile nature of several sulfhydrated products generated from electrophiles, such as 8-SH-cGMP, 15d-PGJ2-SH and even sulfhydrated adducts of HNE and acrolein, may reflect their high nucleophilic potential. Thus, secondary redox reactions of nucleophiles derived from HS−-dependent electrophile sulfhydration are expected to affect the biological stability and detection of these sulfhydrated adducts once they are formed in cells. For example, the amounts of 8-SH-cGMP formed in A549 and HepG2 cells were smaller than expected on the basis of the amounts of HS− produced in the same cells, as assessed by LC-ESI-MS/MS described below (Figs. 3b and 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7c); C6 cells, however, did not show the same result (Supplementary Fig. 7d). The small amounts of 8-SH-cGMP that were detected compared with the amount of HS− generated may thus be due to instability induced by the nucleophilicity of 8-SH-cGMP. This view is substantiated by the finding that cell treatment with PEG-derivatized SOD (PEG-SOD) and catalase (PEG-catalase) significantly improved the recovery of 8-SH-cGMP and simultaneously reduced cGMP formation from 8-nitro-cGMP administered to A549 cells in culture (P < 0.05; Fig. 3e). Because cGMP, a desulfhydrated product of 8-SH-cGMP, is metabolized by a diversity of cellular phosphodiesterases (PDEs), oxidative desulfhydration by HS− may also contribute to physiological decomposition of 8-nitro-cGMP.

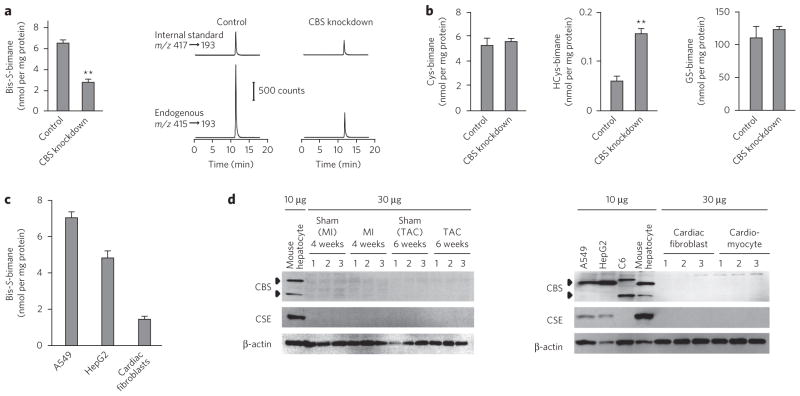

Figure 4. Cellular HS− formation and its physiological relevance to electrophile metabolism.

(a) Quantification by LC-ESI-MS/MS coupled with a monobromobimane-based assay of HS− formed by A549 cells treated with CBS siRNA or untreated cells. Data represent mean ± s.d. (n = 3). **P < 0.01. CBS knockdown was confirmed by western blot (Supplementary Fig. 7b). (b) Quantification of low-molecular-weight thiols in A549 cells with and without CBS knockdown. Data represent mean ± s.d. (n = 3). **P < 0.01. GS-bimane, glutathione-bimane. (c) Comparison of HS− production in cultured cells. Data represent mean ± s.d. (n = 3). (d) Western blots for expression of CBS and CSE in various cultured cells and rat cardiac cells. Mouse cardiac tissues were analyzed 4 weeks after sham operation or myocardial infarction or 6 weeks after sham operation or TAC (top). Cultured cells (A549, HepG2, C6, mouse hepatocytes) and rat cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes were analyzed for expression of CBS and CSE. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Figure 18.

HS− formation in cells and myocardial tissues

The electrophilic fluorogenic reagent monobromobimane, typically used to analyze thiols, undergoes HS−-dependent sulfhydration to yield a bis-S-bimane derivative15. We capitalized on this bimane reaction for sensitive and specific HS− measurement using LC-ESI-MS/MS (Supplementary Fig. 7a) and detected remarkable endogenous HS− generation in A549 and HepG2 cells and cells in primary culture, specifically rat cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 4). CBS knockdown greatly suppressed the extent of HS− generation in A549 cells (Fig. 4a). Other cell lines, including HepG2 and C6 cells, also showed suppressed HS− generation after CBS knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 7c,d).

A technical advantage of bimane sulfhydration analysis by LC-ESI-MS/MS is the ability to measure in parallel all low-molecular-weight sulfhydryls: not only HS− but also cysteine, HCys and GSH. For example, the amounts of intracellular cysteine and GSH were not altered by cell treatment with CBS siRNA (Fig. 4b). CBS siRNA treatment of cells reduced only amounts of HS− and instead increased the intracellular level of HCys, a substrate for CBS that accumulated after CBS knockdown (Fig. 4a,b), suggesting the critical involvement of HS− rather than other cysteine-related derivatives in electrophile metabolism, particularly for 8-nitro-cGMP. This suggestion is supported by the fact that the pKa values of these cysteine-related compounds (8.3, 10.0 and 8.8 for cysteine, HCys and GSH, respectively16,17) are much higher than that of H2S (6.7), which indicates higher nucleophilic reactivity of HS− compared with other compounds at more physiological pH values, as its nucleophilicity is determined by its low pKa18.

Bimane sulfhydration analysis also showed much lower HS− production in primary cultures of cells (for example, rat cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts) compared with cultures of all tumor cell lines examined (Fig. 4c). Lower CBS and CSE expression in these primary cell cultures was also evident, as compared with that in mouse hepatocytes and tumor cell lines (A549, HepG2 and C6 cells) (Fig. 4d). The finding that myocardial cells and tissues produced less HS− than the other cells studied suggests that the amount of endogenous HS− in the heart may be limiting in the context of the amounts of endogenous electrophiles that can be generated during both basal metabolism and inflammatory responses. In other words, myocardial cells may be relatively sensitive to endogenous electrophiles, particularly when they are generated excessively during inflammatory processes.

Notably, HS− is a ubiquitous constituent of many buffers and cell culture media and is not just a product of the cysteine biosynthetic enzymes CBS and CSE13,19. For example, fresh DMEM contained an appreciable amount of HS− (Supplementary Fig. 7e). Therefore, HS− rather than H2S gas may be widely distributed endogenously, in equilibrium with environmental sources and as a byproduct of the decay of more complex thiols. Because HS− can act partly as a potent quencher of various electrophiles, even trace amounts of this ubiquitous mediator will affect the detection and actions of endogenously generated electrophiles in biological systems.

Electrophilic H-Ras activation is regulated by HS−

Recent studies of oxidative inflammatory reactions suggest that an H-Ras oncogenic cellular response can be induced by NO− or RNOS-derived species and the electrophile 15d-PGJ2 (refs. 20,21), which in turn may activate p53-dependent cellular senescence22,23. We examined the effect of exogenously administered or endogenous HS− in this context, focusing on an electrophilic signaling pathway mediated by H-Ras and p53 that may be activated by 8-nitro-cGMP or other electrophiles formed in cells.

Because less HS− was produced—that is, endogenous HS− may have been in short supply relative to the amount of endogenous electrophiles in myocardial cells and tissues (Fig. 4)—we evaluated pharmacological activities of HS− in cardiac cells and in an in vivo model of cardiac inflammatory injury. To clarify the physiological functions of HS−, we induced myocardial hypertrophy and allied chronic inflammatory tissue responses in mouse models of myocardial infarction and pressure overload generated via transverse aortic constriction (TAC) (Supplementary Fig. 8). Chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide24, and both myocardial infarction and TAC models manifest chronic heart failure. Inflammatory reactions that evoke oxidative stress and nitrative stress induced by NO and ROS have been implicated in the genesis of chronic heart failure25,26, findings supported by our immunohistochemical detection of nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-dependent 8-nitro-cGMP formation in the TAC-induced hypertrophic heart and in non-infarcted heart lesions after myocardial infarction (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Substantial 8-nitro-cGMP production, which depended on inducible NOS (iNOS) expression and activity, was strongly inhibited by NaHS treatment of mice after myocardial infarction (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 8d). NaHS treatment had no appreciable effects on the tyrosine nitration reaction occurring in cardiac tissues, as assessed by immunohistochemistry and HPLC-based electrochemical detection analysis for 3-nitrotyrosine (Supplementary Fig. 9a)4. Continuous administration of NaHS to mice after myocardial infarction led to elevated plasma HS− (4.9 ± 0.4 μM (n = 4; vehicle control) versus 7.1 ± 1.3 μM (n = 7; NaHS-treated)), determined via an LC/MS/MS bimane assay at 4 weeks after myocardial infarction (P < 0.05; Student’s t-test). Other metabolic pathways related to cGMP biosynthesis and degradation, such as those involving soluble guanylate cyclase and PDEs, were not affected by the same treatment (Supplementary Fig. 9b,c). This observation confirms pronounced pharmacological actions of HS− and subsequent electrophile sulfhydration in vivo in cardiac cells and tissues.

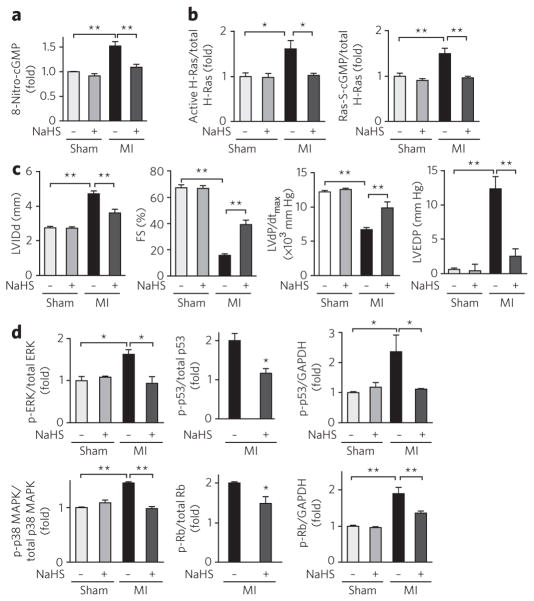

Figure 5. Electrophilic H-Ras activation regulated by HS− in cells and in vivo in cardiac tissues.

(a) Immunohistochemical determination of 8-nitro-cGMP formation in mouse hearts after myocardial infarction (MI) after NaHS treatment or in untreated (vehicle) hearts (original images are in Supplementary Fig. 8d). Data represent mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01. (b) Quantitative data for western blots of H-Ras activation and S-guanylation in mouse hearts (original blots are in Supplementary Fig. 8f). Data represent mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (c) Protective effects of HS− on chronic heart failure caused by myocardial infarction. Cardiac functions of mice after myocardial infarction or sham operation and treated with NaHS or untreated (treated with vehicle). LV IDd, left ventricular end-diastolic internal diameter; FS, fractional shortening; dP/dtmax, maximal rate of pressure development; EDP, end-diastolic pressure. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01. (d) Quantitative data for western blots measuring amount of phosphorylation (p-) of ERK, p38 MAPK, p53 and Rb and expression of ERK, p38 MAPK, p53 and Rb in mouse hearts after myocardial infarction (original blots are in Supplementary Fig. 8f). Because western blotting detected no expression of Rb and p53 in sham-operated mouse hearts, the amounts of phosphorylation of p53 and Rb were compared after normalization with GAPDH as an internal control. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

We then investigated H-Ras activation in cardiac tissue in which increased iNOS expression and concomitant 8-nitro-cGMP production occurred. Affinity capture analyses were used to detect H-Ras activation in the tissues. Western blotting of proteins involved in myocardial infarction– and TAC-induced chronic heart failure showed H-Ras activation and simultaneous S-guanylation of activated H-Ras pulled down from hypertrophic cardiac tissue (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 8e). NaHS treatment also fully inhibited H-Ras activation and concomitant H-Ras S-guanylation in mouse hearts after myocardial infarction (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 8f).

NaHS treatment in vivo after myocardial infarction greatly improved dilation of the left ventricle and limited its dysfunction in mice, although ischemic scars were equally developed in hearts of both NaHS- and vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 2). A critical downstream cellular response to Ras activation is mediated by ERK, p38 MAPK and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), which have a central role in cardiac hypertrophy27. Sustained activation of ERK and p38 MAPK then induces activation of p53 and Rb, which have a critical function in cellular senescence22,23 and the transition from hypertrophy to heart failure28,29. NaHS treatment strongly suppressed the activation of ERK and p38 MAPK. Furthermore, phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, ERK, p53 and Rb increased in mouse hearts after myocardial infarction, with NaHS suppressing their activation (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 8g). These results confirm that HS− attenuates left ventricle dilation and dysfunction after myocardial infarction, in part by suppressing myocardial cell S-guanylation–dependent activation of H-Ras and its downstream signaling pathways.

We identified high HS− production (Fig. 4) and constitutive expression of different NOS isoforms30,31 in A549 cells and identified concomitant baseline protein S-guanylation by endogenous 8-nitro-cGMP, as evidenced by western blot analysis (Fig. 1a,b). Strong H-Ras activation was induced by CBS knockdown in A549 cells, with simultaneous S-guanylation of activated H-Ras pulled down from the same cell lysates (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Such elevated S-guanylation and activation of H-Ras induced by CBS knockdown were completely nullified by addition of NaHS. The same enhancement of H-Ras activation by S-guanylation was observed when 8-nitro-cGMP was added to cultured A549 cells (Supplementary Fig. 10b). This observation confirmed the substantial contribution of elevated endogenous 8-nitro-cGMP, generated by CBS knockdown, to H-Ras activation. Although an involvement of endogenous HNE formation was not evident, marked activation of H-Ras via S-alkyl adduction occurred in HNE-treated A549 cells and was inhibited by CBS-derived HS− (Supplementary Fig. 10c). These data reveal that HS− can regulate cellular electrophilic signaling involving H-Ras via electrophile sulfhydration reactions.

Electrophilic H-Ras signaling regulated by HS−

iNOS-dependent H-Ras S-guanylation concomitant with H-Ras activation was confirmed with rat cardiac fibroblasts in culture with or without iNOS knockdown after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation to generate endogenous 8-nitro-cGMP (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 11a). Suppression of iNOS expression by the siRNA resulted in almost complete abrogation of H-Ras S-guanylation and activation in the cardiac fibroblasts. Site-specific H-Ras S-guanylation and its inhibition by HS− were verified in a cell-free reaction mixture via western blotting and proteomic analysis of recombinant H-Ras and its C184S mutant treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 11b). LC/MS/MS sequencing analysis revealed that only Cys184 of H-Ras was S-guanylated (Fig. 6b). Thus, H-Ras Cys184 is a highly susceptible nucleophilic sensor for 8-nitro-cGMP–induced protein S-guanylation.

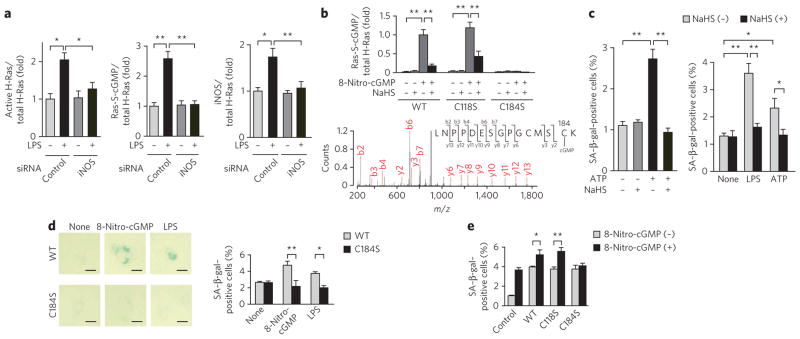

Figure 6. HS− regulation of H-Ras electrophile sensing and signaling.

(a) Suppression of LPS-induced iNOS expression, S-guanylation and activation of H-Ras by iNOS knockdown in rat cardiac fibroblasts in culture. (b) Identification of the S-guanylation site in H-Ras. Top, quantitative data for western blotting of S-guanylation in recombinant H-Ras (wild-type (WT) and C118S and C184S mutants) treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM) and its suppression by NaHS (100 μM). Bottom, MS identification of S-guanylation at Cys184 in recombinant H-Ras treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM). (c) Induction of rat cardiomyocyte senescence by ATP (100 μM) treatment (left) and in cardiac fibroblasts stimulated with LPS and ATP (right) and their suppression by NaHS (100 μM). Cells were stimulated with LPS (1 μg ml−1) or ATP (100 μM) for 3 h, followed by incubation in 0.5% (v/v) serum-containing medium for 4 d. In some experiments, cells were pretreated with 100 μM NaHS for 1 h before stimulation with LPS or ATP. (d) Senescence induction of rat cardiac fibroblasts expressing WT or H-RasC184S by 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM) or LPS (1 μg ml−1). Scale bars, 20 μm. (e) 8-Nitro-cGMP–induced (10 μM) senescence of rat cardiac fibroblasts transfected with control vector or vectors expressing wild-type H-Ras or H-RasC118S or H-RasC184S mutants. In c and d, cell senescence was determined by SA–β-gal staining with quantitative analysis. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Original images for a–c and e are shown in Supplementary Figure 11.

Oxidative stress–related nucleotides that induce DNA and nucleotide damage and activation of oncogenic Ras can induce cellular senescence via p53 and Rb tumor suppressor pathways22,23 (Supplementary Fig. 12). Thus, we investigated how 8-nitro-cGMP formation may promote cardiac cell senescence. Exogenously administered 8-nitro-cGMP, but not NO or cGMP, caused growth arrest and remarkably increased the senescence of cultured rat cardiac fibroblasts, with NaHS treatment limiting these responses (Supplementary Fig. 11c,d). The 8-nitro-cGMP–related senescence responses of the cultured cardiomyocytes were comparable to those of cells expressing RasG12V, a constitutively active form of Ras (Supplementary Fig. 11e). Therefore, the impact of site-specific H-Ras Cys184 S-guanylation was evaluated in the context of downstream signaling reactions leading to cellular senescence of cultured rat cardiac fibroblasts. Enhanced senescence of fibroblasts occurred after 8-nitro-cGMP treatment or after stimulation with LPS to generate endogenous 8-nitro-cGMP (Fig. 6c–e and Supplementary Figs. 11 and 13). Both LPS and ATP induce iNOS expression and NO synthesis in cardiac cells32. Here, ATP addition activated cultured cardiomyocytes to generate 8-nitro-cGMP, the amounts of which corresponded to the degree of protein S-guanylation (Supplementary Fig. 13a). This generation of 8- nitro-cGMP induced cellular senescence (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 11f, g). NaHS treatment markedly attenuated 8-nitro-cGMP formation and protein S-guanylation, which resulted in suppression of cellular senescence induced by electrophilic stimulation in these cultured rat cardiac cells (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 13). The senescence occurred only when cells expressed wild-type H-Ras or the H-RasC118S mutant but not the H-RasC184S mutant (Fig. 6d,e and Supplementary Fig. 11h).

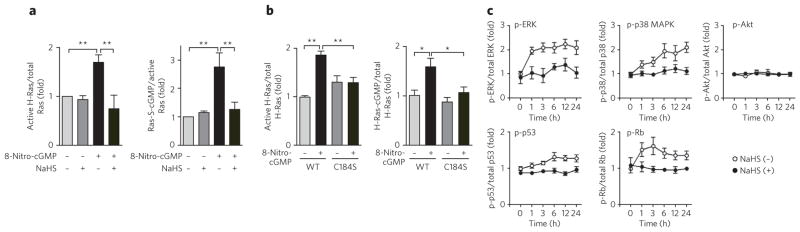

Treatment of cultured rat cardiomyocytes with 8-nitro-cGMP also induced H-Ras activation with simultaneous H-Ras S-guanylation, which was strongly inhibited by NaHS treatment (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 14a). Moreover, activation of H-Ras, but not of the H-RasC184S mutant, was induced in the membrane preparation of rat cardiac fibroblasts after treatment with 8-nitro-cGMP (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 14b). Inhibition of ERK, p38 MAPK and PI3K greatly suppressed 8-nitro-cGMP–induced cardiac senescence (Supplementary Fig. 14c,d). In contrast, treatment of cardiomyocytes with 8-nitro-cGMP induced sustained activation of ERK, p38 MAPK, p53 and Rb but not of Akt, a downstream effector of class I PI3K, which was nullified by the NaHS treatment (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 14e). We conclude that Cys184 of H-Ras is a functionally critical sensor of endogenous electrophilic species, such as 8-nitro-cGMP, in their H-Ras–dependent downstream signal transduction.

Figure 7. 8-Nitro-cGMP–induced H-Ras activation in cardiac cells and their suppression by HS−.

(a) 8-Nitro-cGMP–induced H-Ras activation with its concomitant S-guanylation in rat cardiomyocytes and their suppression by HS−. Rat cardiomyocytes were pretreated with NaHS (100 μM) for 24 h, followed by incubation with 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM) for 4 d. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01. (b) 8-Nitro-cGMP–induced activation of H-Ras via S-guanylation at Cys184 in membrane preparation of rat cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiac membranes expressing GFP-fused WT H-Ras or H-RasC184S mutants were treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM) for 1 h. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (c) Time courses of phosphorylation (p-) of ERK, p38 MAPK, Akt, p53 and Rb induced by 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM) in rat cardiomyocytes. Cells were untreated or treated with NaHS (100 μM) 24 h before 8-nitro-cGMP treatment. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Original western blots for a–c are shown in Supplementary Figure 14.

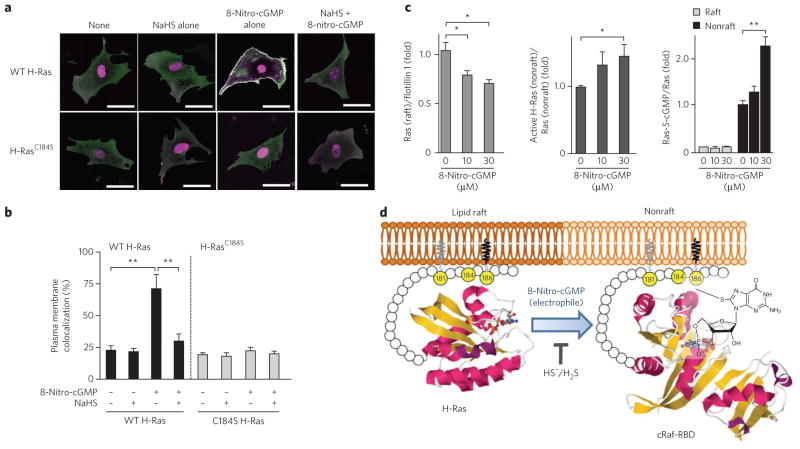

Among Ras isoforms, only H-Ras contains two palmitoylation sites (Cys181 and Cys184), and palmitoylation of Ras proteins has a key role in their localization and activity33. Monopalmitoylation of Cys181, but not Cys184, was sufficient to target H-Ras to the plasma membrane, and GDP-bound H-Ras was detected predominantly in lipid rafts (Supplementary Fig. 12)34,35. GTP loading of H-Ras released H-Ras from the rafts to become more diffusely distributed in the plasma membrane, an event necessary for efficient activation of Raf 34. Although the GFP-fused H-Ras and the DsRed-fused Ras-binding domain of cRaf (cRaf-RBD) proteins did not colocalize in cardiac fibroblasts, treatment with 8-nitro-cGMP induced association of H-Ras with cRaf-RBD near the plasma membrane (Fig. 8a,b and Supplementary Fig. 16a,b). Such 8-nitro-cGMP–dependent colocalization of H-Ras and Raf was not observed in the cells transfected with the H-RasC184S mutant (Fig. 8a,b and Supplementary Fig. 16a,b). This observation indicates that 8-nitro-cGMP promotes activation of H-Ras in the plasma membrane. Because Cys184 palmitoylation leads to the correct GTP-regulated lateral segmentation of H-Ras between lipid rafts and nonraft microdomains33–35, S-guanylation of H-Ras at Cys184 is expected to redistribute H-Ras from rafts into the bulk plasma membrane. Remarkably, application of 8-nitro-cGMP to the lipid raft fraction isolated from adult rat hearts induced dissociation of GDP-bound H-Ras from rafts, and this H-Ras, no longer associated with a raft and concomitantly S-guanylated, preferentially interacted with cRaf-RBD (Fig. 8c and Supplementary Fig. 16c). The GDP-bound H-Ras without S-guanylation was left in rafts. NaHS treatment completely suppressed 8-nitro-cGMP–induced colocalization of H-Ras with cRaf-RBD and H-Ras dissociation from rafts. These results indicate that S-guanylation of H-Ras at Cys184 releases H-Ras from lipid rafts and that released H-Ras binds Raf, which leads to activation of downstream signaling pathways (Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 12).

Figure 8. Dissociation of H-Ras from rafts and its activation induced by H-Ras Cys184 S-guanylation.

(a) 8-Nitro-cGMP–induced colocalization of H-Ras with the Ras-binding domain (RBD) at the plasma membrane of rat cardiac fibroblasts. Cells expressing GFP-fused H-Ras and DsRed-fused cRaf-RBD proteins were pretreated for 3 h with cycloheximide (50 μg ml−1) and then incubated for 3 h in cycloheximide with or without NaHS (100 μM). Then, cells were untreated or treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM) for 3 h. Merge images of GFP-fused H-Ras and DsRed-fused cRaf-RBD are shown (individual images of GFP-fused H-Ras, DsRed-fused cRaf-RBD, differential interference contrast (DIC) images are in Supplementary Fig. 16a,b). Scale bars, 50 μm. (b) Quantitative data obtained from morphometric analysis for colocalization of H-Ras and cRaf-RBD at the plasma membrane shown in a. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. **P < 0.01. (c) 8-Nitro-cGMP–induced H-Ras dissociation from rafts with concomitant S-guanylation and the implication of this dissociation in H-Ras activation. Western blotting of H-Ras, flotillin 1 and S-guanylated H-Ras for the raft fraction and active H-Ras, S-guanylated H-Ras and H-Ras for the nonraft fraction in the presence or absence of 8-nitro-cGMP (uncropped blots are in Supplementary Fig. 16c). Data represent mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (d) Schematic model showing activation of H-Ras induced by 8-nitro-cGMP. Gray lipid indicates palmitoylation (at Cys181), and black lipid indicates isoprenylation (at Cys186). The yellow balls are cysteine residues. Magenta ribbons represent α-helices, and yellow ribbons represent β-sheets. T indicates that HS−/H2S inhibits the reaction mediated by the electrophile 8-nitro-cGMP. The three-dimensional structures of H-Ras and Raf-RBD were obtained from the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 3L8Z (right) and 3KUD (left).

DISCUSSION

This study reveals that enzymatically generated HS− regulates the metabolism and signaling actions of various electrophiles and that HS−-induced electrophile sulfhydration regulates electrophile-mediated redox signaling. Although H2S is proposed to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, NaHS treatment produced no appreciable suppression of iNOS and NADPH oxidase (Nox2) expression and 3-nitrotyrosine formation in a mouse model of ischemic heart injury (Supplementary Figs. 9a and 15a). NaHS treatment also did not affect LPS-induced ROS production and ATP-induced RNOS generation in cardiac cells and C6 cells in culture (Supplementary Fig. 15b,c). In view of the modest rate constants for the reaction of H2S with ROS and RNOS such as H2O2 and ONOO− (ref. 36), HS− is not expected to directly scavenge oxygen or NO-derived reactive species, unless they have a substantial electrophilic character. Moreover, some potential HS− targets such as the ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels37 and PDEs38 may be responsible for cardioprotection observed with HS− treatment. However, inhibition of KATP channels, protein kinase A or protein kinase G did not affect NaHS-induced suppression of cardiac cell senescence caused by 8-nitro-cGMP (Supplementary Fig. 14f,g). Also, NaHS treatment had no effect on cGMP metabolic pathways in vivo and in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 9b,c). Therefore, an unambiguous cause-and-effect relationship in terms of HS− regulation of electrophile-evoked cellular stress responses leading to cellular senescence exists. H2S, behaving as an anion (HS−) rather than as a gaseous molecule, reacts as a nucleophile to induce the sulfhydration of the electrophile. This results in cardioprotection in a model of heart failure after myocardial infarction by suppressing oxidative stress–induced or electrophile-mediated (for example, by 8-nitro-cGMP) cellular senescence.

Ras proteins have three isoforms, which generate distinct signal outputs despite interacting with a common set of effectors33. These biological differences can be accounted for by the 25 C-terminal amino acids of the hypervariable domain, which may contain a protein structure required for Ras to associate with the inner membrane. Cys184 of H-Ras is one of two palmitoylation sites located at its C-terminal domain. Monopalmitoylation of Cys181 is required and sufficient for efficient trafficking of H-Ras to the plasma membrane35. Although Cys184 is not essential for targeting H-Ras to the plasma membrane, it is required for control of GTP-regulated lateral segmentation of H-Ras between lipid rafts and nonrafts, which is necessary for efficient activation of Raf34,35. In addition, inhibition of Cys184 palmitoylation efficiently delivers H-Ras to the plasma membrane with little Golgi pooling35, suggesting that S-guanylation of H-Ras at Cys184 promotes H-Ras plasma membrane localization and association with Raf by causing its dissociation from lipid rafts. Cys184 of H-Ras may be chemically modified not only by 8-nitro-cGMP but also by HNE and 15d-PGJ2, and this H-Ras, thereby modified, may increase interaction with cRaf-RBD (Supplementary Fig. 16d–g). Moreover, the electrophilic adduction causes precise structural alterations such that H-Ras is accessible to the effector molecule Raf, which, in turn, readily transduces electrophile-mediated signaling to downstream phosphorylation signaling pathways (Supplementary Fig. 12)22,39. Although the GTP-bound Ras also bound class I PI3K, S-guanylation of H-Ras never activated Akt (Fig. 7c). However, inhibition of PI3K strongly suppressed 8-nitro-cGMP–induced cardiac cell senescence (Supplementary Fig. 14), which suggests that another class of PI3K may be involved in H-Ras–mediated cardiac senescence. Electrophile adduction of H-Ras at Cys184 induced cellular senescence through kinase-dependent signaling pathways, and thus Cys184 is a facile redox sensor for any endogenous and exogenous electrophiles and their regulation by endogenous HS− via sulfhydration (Supplementary Fig. 12).

8-SH-cGMP still has cGMP activity, in that it effectively activates PKG (Supplementary Fig. 9d). Moreover, it can acquire PDE resistance, which will increase its pharmacological effects as a cGMP analog (Supplementary Fig. 9e). Because cGMP itself reportedly has a potent cardioprotective effect, sulfhydration of 8-nitro-cGMP may thus alter its chemical properties so that it can benefit not only chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction but also various other disease processes. Thus, although 8-nitro-cGMP formed in excess in the heart after myocardial infarction may accelerate heart remodeling, HS− generation in cells and tissues may rectify the pharmacological actions of this electrophilic cGMP analog, for example, by converting the pathological effects of 8-nitro-cGMP into beneficial effects associated with a PDE-resistant cGMP homolog. A similar HS−-mediated bioconversion of an electrophile to a nucleophile would apply to other electrophiles, such as 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 3a).

p53-dependent G1 cell cycle arrest aids DNA repair of injured cells to prevent oxidative stress–related genetic mutation and genotoxicity. Abundant GTP in the cellular nucleotide pool seems to be nitrated initially and thus may function as a sensor for nucleotide modification caused by RNOS12; this step is believed to be crucial for a cellular oxidative stress response. Also, 8-nitro-GTP becomes an endogenous mutagen when incorporated into DNA40,41. Therefore, soluble guanylate cyclase not only contributes to electrophilic 8-nitro-cGMP signaling but also can suppress 8- nitro-GTP and limit mutagenic responses (Supplementary Fig. 12). Thus, 8-nitro-cGMP regulation by HS− limits nitrative modification via sulfhydration, supporting positive genomic and signaling functions and conferring protection against ROS- and RNOS-induced genotoxicity.

In conclusion, our present data reveal an important metabolic relationship between HS− and oxidative inflammation–derived electrophilic signaling mediators. This identification of HS−-induced electrophile sulfhydration as a mechanism for terminating electrophile-mediated signaling provides a fundamental new way of understanding the regulation of redox cellular signaling and therapeutic strategies for inflammation-related diseases.

METHODS

RNAi screening

To clarify factors contributing to regulation of 8-nitro-cGMP signaling, we performed RNAi screening, as described in Supplementary Methods. Detailed protocols and siRNAs used are described in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

Reaction of electrophiles with HS− in vitro

8-Nitro-cGMP (100 μM) was reacted with various concentrations of NaHS (the HS− donor) in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) at 37 °C for 5 h. The reaction of 8-nitro-cGMP (100 μM) with NaHS (1 mM) was also carried out in the absence or presence of additives including cysteine (100 μM), metals (150 μM) and metal-containing compounds and proteins (10 μM). Reaction products of 8-nitro-cGMP with NaHS in the absence or presence of additives were analyzed by using RP-HPLC and LC/MS as described in Supplementary Methods. 15d-PGJ2 (1–10 μM) was reacted with NaHS (0–1,000 μM) in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 2 h. The reactions of 1,2-NQ (100 μM), 1,4-NQ (100 μM), tert-butylbenzoquinone (100 μM) or OANO2 (100 μM) with NaHS (50–800 μM) were carried out in 200 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) at 25 °C for 1 h.

Determination and quantitation of cellular 8-SH-cGMP formation

A549, HepG2 and C6 cells treated with CBS siRNA or untreated cells were incubated with 8-nitro-cGMP (200 μM) in serum-free DMEM at 37 °C for 6 h. 8-SH-cGMP that formed in those cultures was quantified by means of LC-ESI-MS/MS with the use of 8-34SH]-cGMP as an internal standard. Details are in Supplementary Methods.

Measurement of cellular production of HS− and intracellular thiol derivatives

Cellular production of HS− was quantified by means of LC-ESI-MS/MS with monobromobimane derivatization. This protocol allowed us to simultaneously quantify HS− and other low-molecular-weight thiols including cysteine, HCys and GSH, as described in Supplementary Methods.

Animals and surgery

All protocols using mice and rats were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, Kyushu University. Mice with a homozygous deletion of the gene encoding iNOS were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. The left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was ligated (with 6-0 silk suture) near its origin between the pulmonary outflow tract and the edge of the left atrium. Acute myocardial ischemia was deemed successful when the anterior left ventricle wall became cyanotic and the electrocardiogram showed obvious ST segment elevation. Sham-operated mice were subjected to the same procedure, except that the suture around the LAD was not tied. TAC surgery was performed on 6-week-old male C57BL/6J mice. A mini-osmotic pump (Alzet) filled with vehicle (PBS) or NaHS (50 μmol kg−1 d−1) was implanted intraperitoneally into 8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice 1 d after LAD ligation. Plasma concentrations of HS− were determined by means of LC-ESI-MS/MS with monobromobimane as described in Supplementary Methods.

Immunological measurement of 8-nitro-cGMP production in vivo

Paraffin-embedded left ventricle sections (5 μm thick) were stained with 8-nitro-cGMP (1G6)–specific antibody (1:1,000), followed by visualization with Alexa Fluor 488 rabbit-specific IgG (clone no. A11008) and Alexa Fluor 546 mouse-specific IgG (clone no. A11003) antibodies (1:1,000; Invitrogen). Digital photographs were taken at 600× magnification with a confocal microscope (FV10i, Olympus).

Purification of H-Ras

Recombinant human H-Ras was prepared and purified as described in Supplementary Methods.

Pulldown assay and western blotting

Endogenous active H-Ras was obtained by incubating supernatants with glutathione S-transferase–fused cRaf-RBD in the presence of GSH-Sepharose beads, followed by western blotting as described in Supplementary Methods.

Identification of S-guanylation sites in H-Ras

S-Guanylation sites were identified by means of MS with trypsin-digested peptide fragments of H-Ras. Details are in Supplementary Methods.

Isolation of cardiac cells and measurement of cell senescence

Cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts were prepared from ventricles of 1- to 2-d-old Sprague-Dawley rats. Cardiac fibroblasts were transfected with control vector or vectors expressing H-Ras (wild-type or carrying the C118S or C184S mutation) via electroporation (1,100 V, 10 ms × 4; NeonTM Transfection System, Life Technologies Corporation). Cardiomyocytes were infected with recombinant adenoviruses expressing LacZ control or RasG12V at 100 multiplicity of infection 1 h after serum starvation. Twenty-four hours later, cells were pretreated with NaHS (100 μM) for 24 h and then were treated with ATP (100 μM), LPS (1 μg ml−1) or 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μM) for 3 h, after which they were cultured for 4 d in 0.5% (v/v) serum-containing medium. Cardiac cells plated on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde neutral buffer solution, and cellular senescence was assessed by measuring endogenous β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity using a senescence-associated β-gal (SA-β-gal) staining kit (Cell Signaling). Digital photographs were taken at 200× magnification with a Biozero microscope (BZ-8000; Keyence), and the number of β-gal–positive cells (n > 100 cells) was calculated by using the BZ-II Analyzer (Keyence), with colorimetric intensity adjusted as the percentage of basal senescent cells approached 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography and cardiac catheterization

Echocardiography was performed in anesthetized mice (50 mg per kg body weight pentobarbital sodium) via the Nemio XG echocardiograph (Toshiba) equipped with a 14-MHz transducer. A 1.4-French micronanometer catheter (Millar Instruments) was inserted into the left carotid artery and advanced retrograde into the left ventricle. Hemodynamic measurements were recorded when the heart rate was stabilized within 500 ± 10 beats per min.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± s.e.m. of at least three independent experiments unless specified. Statistical comparisons were made with two-tailed Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls procedure, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Other methods

Detailed information is available in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J.B. Gandy for her editing of the manuscript. Thanks are also due to T. Okamoto, S. Fujii, Md. M. Rahaman, S. Khan, K.A. Ahmed, J. Yoshitake, T. Matsunaga, M.H.A. Rahman, J. Sakamoto, J. Minkyung, K. Hara, M. Goto, F. Sohma, K. Taguchi, T. Miura, T. Toyama, Y. Shinkai, I. Ishii and M. Toyataka for technical assistance; S. Kasamatsu, T. Ida and K. Kunieda for 8-nitro-cGMP preparation; Y. Kawai for technical assistance with LC/MS/MS experiments; H. Arimoto for helpful discussion; and J. Wu for reading our paper to evaluate its concepts and interdisciplinary accessibility. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Research in a Proposed Area) from the Ministry of Education, Sciences, Sports and Technology, Japan; a grant from the Japan Science and Technology Agency PRESTO program; grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan; and grants from the US National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.N., T.A. and T. Sawa designed the experiment, performed analysis and wrote the paper; N.K., H. Inoue and T. Shibata performed MS analysis, cell biology and mouse and rat studies; K.O., H. Ihara, H.M., H.K., M.S. and M.Y. performed data analyses; B.A.F., A.v.d.V., K.U. and Y.K. designed the experiment and edited the paper.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the online version of the paper.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to T.A.

References

- 1.Kajimura M, Fukuda R, Bateman RM, Yamamoto T, Suematsu M. Interactions of multiple gas-transducing systems: hallmarks and uncertainties of CO, NO, and H2S gas biology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:157–192. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Rose P, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide and cell signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:169–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fridovich I. The biology of oxygen radicals. Science. 1978;201:875–880. doi: 10.1126/science.210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawa T, et al. Protein S-guanylation by the biological signal 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:727–735. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee SG. Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Autréaux B, Toledano MB. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:813–824. doi: 10.1038/nrm2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akaike T, Fujii S, Sawa T, Ihara H. Cell signaling mediated by nitrated cyclic guanine nucleotide. Nitric Oxide. 2010;23:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudolph TK, Freeman BA. Transduction of redox signaling by electrophile-protein reactions. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.290re7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forman HJ, Fukuto JM, Torres M. Redox signaling: thiol chemistry defines which reactive oxygen and nitrogen species can act as second messengers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C246–C256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00516.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaki MH, et al. Cytoprotective function of heme oxygenase 1 induced by a nitrated cyclic nucleotide formed during murine salmonellosis. J Immunol. 2009;182:3746–3756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchida K, Shibata T. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2: an electrophilic trigger of cellular responses. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:138–144. doi: 10.1021/tx700177j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii S, et al. The critical role of nitric oxide signaling, via protein S-guanylation and nitrated cyclic GMP, in the antioxidant adaptive response. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23970–23984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes MN, Centelles MN, Moore KP. Making and working with hydrogen sulfide: the chemistry and generation of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and its measurement in vivo: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiranti V, et al. Loss of ETHE1, a mitochondrial dioxygenase, causes fatal sulfide toxicity in ethylmalonic encephalopathy. Nat Med. 2009;15:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nm.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wintner EA, et al. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winterbourn CC, Metodiewa D. Reactivity of biologically important thiol compounds with superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:322–328. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glushchenko AV, Jocobsen DW. Molecular targeting of proteins by L-homocysteine: mechanistic implications for vascular disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1883–1898. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LoPachin RM, Gavin T, Geohagen BC, Das S. Neurotoxic mechanisms of electrophilic type-2 alkenes: soft-soft interactions described by quantum mechanical parameters. Toxicol Sci. 2007;98:561–570. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishii I, et al. Murine cystathionine γ-lyase: complete cDNA and genomic sequences, promoter activity, tissue distribution and developmental expression. Biochem J. 2004;381:113–123. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lander HM, et al. Redox regulation of cell signalling. Nature. 1996;381:380–381. doi: 10.1038/381380a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliva JL, et al. The cyclopentenone 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 binds to and activates H-Ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4772–4777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0735842100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu C, Miloslavskaya I, Demontis S, Maestro R, Galaktionov K. Regulation of cellular response to oncogenic and oxidative stress by Seladin-1. Nature. 2004;432:640–645. doi: 10.1038/nature03173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shih H, Lee B, Lee RJ, Boyle AJ. The aging heart and post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YH, et al. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in cardiac function and remodeling in mice with heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2616–H2623. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00546.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang P, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase deficiency protects the heart from systolic overload-induced ventricular hypertrophy and congestive heart failure. Circ Res. 2007;100:1089–1098. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000264081.78659.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelb BD, Tartaglia M. Ras signaling pathway mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: getting into and out of the thick of it. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:844–847. doi: 10.1172/JCI46399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sano M, et al. p53-induced inhibition of Hif-1 causes cardiac dysfunction during pressure overload. Nature. 2007;446:444–448. doi: 10.1038/nature05602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter JJ, Tanaka N, Rockman HA, Ross J, Jr, Chien KR. Ventricular expression of a MLC-2v-ras fusion gene induces cardiac hypertrophy and selective diastolic dysfunction in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23173–23178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.23173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asano K, et al. Constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression, regulation, and activity in human lung epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10089–10093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pechkovsky DV, et al. Pattern of NOS2 and NOS3 mRNA expression in human A549 cells and primary cultured AEC II. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L684–L692. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00320.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishida M, et al. Heterologous down-regulation of angiotensin type 1 receptors by purinergic P2Y2 receptor stimulation through S-nitrosylation of NF-κB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6662–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017640108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hancock JF. Ras proteins: different signals from different locations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prior IA, et al. GTP-dependent segregation of H-Ras from lipid rafts is required for biological activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:368–375. doi: 10.1038/35070050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy S, et al. Individual palmitoyl residues serve distinct roles in H-Ras trafficking, microlocalization, and signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6722–6733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6722-6733.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carballal S, et al. Reactivity of hydrogen sulfide with peroxynitrite and other oxidants of biological interest. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H2S as a novel endogenous gaseous KATP channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bucci M, et al. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous inhibitor of phosphodiesterase activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1998–2004. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.209783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun P, et al. PRAK is essential for ras-induced senescence and tumor suppression. Cell. 2007;128:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshitake J, et al. Nitric oxide as an endogenous mutagen for Sendai virus without antiviral activity. J Virol. 2004;78:8709–8719. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8709-8719.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohshima H, Sawa T, Akaike T. 8-Nitroguanine, a product of nitrative DNA damage caused by reactive nitrogen species: formation, occurrence, and implications in inflammation and carcinogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1033–1045. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.