Abstract

Objective

To make a rapid assessment of the common myths and misconceptions surrounding the causes of cervical cancer and lack of screening among unscreened low-income Zambian women.

Methods

We initiated a door-to-door community-based initiative, led by peer educators, to inform unscreened women about the existence of a new see-and-treat cervical cancer prevention program. During home visits peer educators posed the following two questions to women: 1. What do you think causes cervical cancer? 2. Why haven’t you been screened for cervical cancer? The most frequent types of responses gathered in this exercise were analyzed thematically.

Results

Peer educators contacted over 1100 unscreened women over a period of two months. Their median age was 33 years, a large majority (58%) were not educated beyond primary school, over two-thirds (71%) did not have monthly incomes over 500,000 Zambian Kwacha (US$100) per month, and just over half (51%) were married and cohabiting with their spouses. Approximately 75% of the women engaged in discussions had heard of cervical cancer and had heard of the new cervical cancer prevention program in the local clinic. The responses of unscreened low-income Zambian women to questions posed by peer educators in urban Lusaka reflect the variety of prevalent ‘folk’ myths and misconceptions surrounding cervical cancer and its prevention methods.

Conclusion

The information in our rapid assessment can serve as a basis for developing future educational and intervention campaigns for improving uptake of cervical cancer prevention services in Zambia. It also speaks to the necessity of ensuring that programs addressing women’s reproductive health take into account societal inputs at the time they are being developed and implemented. Taking a community-based participatory approach to program development and implementation will help ensure sustainability and impact.

Keywords: cervical cancer, misconceptions, myths, peer educators

Cervical cancer in Zambia

Globally, an estimated 500,000 women are diagnosed with and over 250,000 die from cervical cancer each year, more than 80% residing in resource-limited nations that have access to less than 5% of global health resources (1,2). Sub-Saharan Africa hosts 12% of the world’s population but accounts for 20% (57,000) of estimated cervical cancer-related deaths (3–5). While access to effective and affordable screening and treatment services is of central importance in the prevention of cervical cancer, myths and misconceptions surrounding both the disease and the prevention modality can act as barriers to their acceptance and adoption.

Zambia has one of the highest cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates in the world (6–8). In January 2006, through support from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-PEPFAR program and other charitable resources, we launched an innovative program for cervical cancer prevention, targeting, but not limited to, HIV seropositive women (9, 10). To date (July 2009) we have established 15 nurse-led clinics and screened over 31,000 women.

Community outreach for improving cervical cancer prevention program uptake

A key component of our program is the use of peer educators as health promotion advocates and patient navigators to enhance client uptake and reduce loss to follow-up. Peer educators are volunteer women selected from the communities surrounding their respective clinics and with an aptitude for voicing health concerns. They use various community-based platforms to inform women of free, walk-in/same-day see-and-treat cervical cancer prevention services in their respective clinic catchment areas. Peer educators are trained to conduct both community-based and one-on-one cervical health promotion talks to women residing in the communities. Women requesting more information or expressing a desire to be screened are ‘navigated’ by the peer educators to the cervical cancer prevention clinics.

As a way of intensifying community education, we recently (April 2009) initiated a door-to-door community-based initiative which involves peer educators making home visits to inform women about the existence of the program and discussing any concerns they may have regarding the screening and treatment process. The community in which the peer educators carried out their door-to door campaign (Bauleni compound) is typical of Lusaka’s peri-urban informal settlements which provide residence for the majority of its low-income citizens. Located 10 km outside of Lusaka’s city center the community of concern has a population of 22,491 and 4,892 households. Water is accessed mostly through communal taps, unemployment rates are high and there is a heavy disease burden of malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. During the door-to-door campaign each of four peer educators involved in the campaign engaged at least 8–10 women, each day, in discussions around cervical cancer. Over 1100 women were reached through the peer educators over a period of two months. Women reached through the campaign had a median age of 33 years, a large majority (58%) were not educated beyond primary school, over two-thirds (71%) did not have monthly incomes over 500,000 Zambian Kwacha (US$100) per month, and just over half (51%) were married and cohabiting with their spouses. Approximately 75% of the women engaged in discussions had heard of cervical cancer and had heard of the ‘see-and-treat’ cervical cancer prevention program in the local clinic.

Rapid assessment for understanding myths and misconceptions

The peer educators were charged with delivering three basic messages to the target population:

Anyone who has ever had sex is at risk for cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer can be prevented or cured if detected early.

It is important to get screened for cervical cancer.

During all forms of community sensitization, including the door-to-door campaign, peer educators posed the following two questions to women:

What do you think causes cervical cancer?

Why haven’t you been screened for cervical cancer?

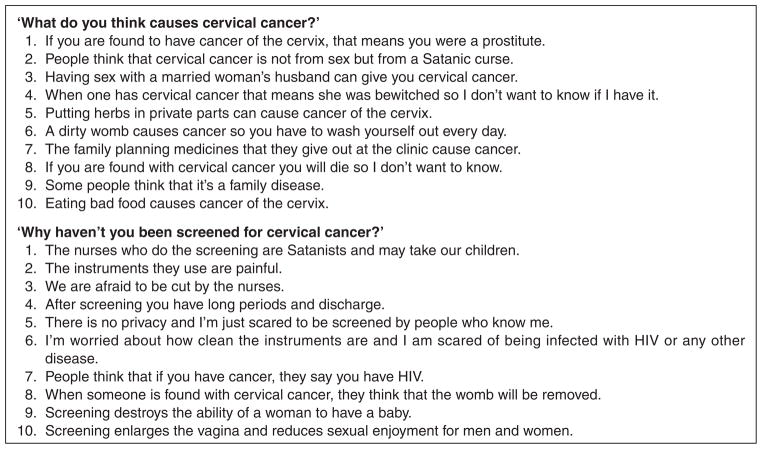

The most frequent types of responses gathered in this rapid information gathering exercise among Zambian women who had never been screened for cervical cancer were analyzed thematically and are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Top ten myths and misconceptions about cervical cancer among previously unscreened women in Lusaka, Zambia

Challenges and opportunities for cervical cancer prevention in Zambia

Facilities for early detection of cervical cancer in sub-Saharan African settings are non-existent for the majority of women. A majority of cervical cancer cases being detected are therefore at an advanced and symptomatic stage, at which time the possibilities of cure are very low. While lack of services is an important determinant of continually high rates of cervical cancer, another important aspect is the apparent lack of knowledge and awareness about the disease. Myths and misconceptions surrounding the disease can lead to poor utilization of screening services wherever they exist. The responses of unscreened Zambian women to questions posed by peer educators in urban Lusaka reflect the variety of prevalent myths and misconceptions surrounding cervical cancer and its prevention methods. Other studies in Africa have shown similar findings (11–14). A ‘folk model’ has recently been proposed to help explain these perceptions as well as the reluctance of women to access screening services even when they are available (14). However, published literature on African women’s own perceptions of cervical cancer as well as their knowledge of screening and treatment procedures is still limited (15).

The information in our rapid assessment can serve as a basis for developing future educational and intervention campaigns for improving uptake of cervical cancer prevention services in Zambia. The combination of service provision interventions along with community-based education and support programs will help ensure that appropriate goals for cancer prevention in the community can be met. From a broader perspective, it is also important to ensure that programs addressing women’s reproductive health needs and concerns take into account societal inputs for developing and implementing program interventions and informational messages (16). Taking a community-based participatory approach to program implementation will assist in the development of eventual programmatic sustainability and increased program impact.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005 Mar-Apr;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang BH, Bray FI, Parkin DM, Sellors JW, Zhang ZF. Cervical cancer as a priority for prevention in different world regions: an evaluation using years of life lost. Int J Cancer. 2004 Apr 10;109(3):418–24. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Wabinga H, Nambooze S, Wabwire-Mangen F. AIDS-related cancers in Africa: maturation of the epidemic in Uganda. AIDS. 1999 Dec 24;13(18):2563–70. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912240-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Vizcaino AP, Skinner ME, Ndhlovu A. Cancer patterns and risk factors in the African population of southwestern Zimbabwe, 1963–1977. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994 Oct-Nov;3(7):537–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006 Jun 15;118(12):3030–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowa K, Wood C, Chao A, Chintu C, Mudenda V, Chikwenya M. A review of the epidemiology of cancers at the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia. Trop Doct. 2009 Jan;39(1):5–7. doi: 10.1258/td.2008.070450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patil P, Elem B, Zumla A. Pattern of adult malignancies in Zambia (1980–1989) in light of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 epidemic. J Trop Med Hyg. 1995 Aug;98(4):281–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parham GP, et al. Prevalence and predictors of squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix in HIV-infected women in Lusaka, Zambia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006 Dec;103(3):1017–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mwanahamuntu MH, et al. Implementation of ‘see-and-treat’ cervical cancer prevention services linked to HIV care in Zambia. AIDS. 2009 Mar 27;23(6):N1–5. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283236e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfaendler KS, Mwanahamuntu MH, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Mudenda V, Stringer JS, Parham GP. Management of cryotherapy-ineligible women in a ‘screen-and-treat’ cervical cancer prevention program targeting HIV-infected women in Zambia: lessons from the field. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Sep;110(3):402–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McFarland DM. Cervical cancer and pap smear screening in Botswana: knowledge and perceptions. Int Nurs Rev. 2003 Sep;50(3):167–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2003.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wellensiek N, Moodley M, Moodley J, Nkwanyana N. Knowledge of cervical cancer screening and use of cervical screening facilities among women from various socioeconomic backgrounds in Durban, Kwazulu Natal, South Africa. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002 Jul-Aug;12(4):376–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosavel M, Simon C, Oakar C, Meyer S. Cervical cancer attitudes and beliefs – a Cape Town community responds on World Cancer Day. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24(2):114–9. doi: 10.1080/08858190902854590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatune JW, Nyamongo IK. An ethnographic study of cervical cancer among women in rural Kenya: is there a folk causal model? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005 Nov-Dec;15(6):1049–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley J, Coffey P, Arrossi S, Agurto I, Bingham A, Dzuba I, et al. Women’s perspectives on cervical screening and treatment in developing countries: experiences with new technologies and service delivery strategies. Women and Health. 2006;43(3):103–21. doi: 10.1300/J013v43n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agurto I, Arrossi S, White S, Coffey P, Dzuba I, Bingham A, et al. Involving the community in cervical cancer prevention programs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005 May;89(Suppl 2):S38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]