Abstract

In our previous studies, phosphorylation-dependent tau mislocalization to dendritic spines resulted in early cognitive and synaptic deficits. It is well known that amyloid beta (Aβ) oligomers cause synaptic dysfunction by inducing calcineurin-dependent AMPA receptor (AMPAR) internalization. However, it is unknown whether Aβ-induced synaptic deficits depend upon tau phosphorylation. It is also unknown whether changes in tau can cause calcineurin-dependent loss of AMPARs in synapses. Here, we show that tau mislocalizes to dendritic spines in cultured hippocampal neurons from APPSwe Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-transgenenic mice and in cultured rat hippocampal neurons treated with soluble Aβ oligomers. Interestingly, Aβ treatment also impairs synaptic function by decreasing the amplitude of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs). The above tau mislocalization and Aβ-induced synaptic impairment are both diminished by the expression of AP tau, indicating that these events require tau phosphorylation. The phosphatase activity of calcineurin is important for AMPAR internalization via dephosphorylation of GluA1 residue S845. The effects of Aβ oligomers on mEPSCs are blocked by the calcineurin inhibitor FK506. Aβ-induced loss of AMPARs is diminished in neurons from knock-in mice expressing S845A mutant GluA1 AMPA glutamate receptor subunits. This finding suggests that changes in phosphorylation state at S845 are involved in this pathogenic cascade. Furthermore, FK506 rescues deficits in surface AMPAR clustering on dendritic spines in neurons cultured from transgenic mice expressing P301L tau proteins. Together, our results support the role of tau and calcineurin as two intermediate signaling molecules between Aβ initiation and eventual synaptic dysfunction early in AD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ1-42, soluble tau, synaptic deficits, dendritic spines, mEPSC, PP2B, cultured rat hippocampal neurons, ADDL, Alzheimer

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a dementia characterized by progressive memory loss, ultimately resulting in an inability to form new memories. The pathological hallmarks of the disease are neuritic plaques, primarily composed of amyloid-β (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles, primarily composed of tau (Blennow et al., 2006). Synaptic deficits are highly correlated with cognitive deficits found in AD patients (Davies et al., 1987; Masliah et al., 1989; DeKosky & Scheff, 1990; Terry et al., 1991; Selkoe, 2002; Blennow et al., 2006). Synaptic deficits identified in the hippocampus of transgenic mice with increased Aβ levels include loss of dendritic spines (Mucke et al., 2000; Lanz et al., 2003), deficits in glutamate receptor signaling (Hsia et al., 1999; Kamenetz et al., 2003; Roberson et al., 2011) and deficits in the expression of LTP (Chapman et al., 1999; Gureviciene et al., 2004). In transgenic mice, spine loss and glutamate receptor deficits occur prior to cognitive decline or neuritic plaque formation, suggesting that they may represent the initial stages of the disease (Hulette et al., 1998; Bennett et al., 2006).

In our prior study, we discovered that tau mislocalizes to dendritic spines in tauP301L-transgenenic mice (a model of frontotemporal dementia) and cultured hippocampal neurons expressing P301L tau. Moreover, the mislocalization of tau correlates with cognitive and synaptic deficits at a time in which neurodegeneration is not observed (Hoover et al., 2010). In various studies using AD-transgenenic mice, tau has been shown to be necessary and sufficient for both cognitive and synaptic deficits (Bennett et al., 2004; Santacruz et al., 2005; Oddo et al., 2006; Roberson et al., 2007; Zempel et al., 2010; Sydow et al., 2011). Tau is typically localized to the axons of neurons; however, in its phosphorylated state tau has been shown to mislocalize to the dendritic compartment (Avila et al., 2004; Ittner et al., 2010; Zempel et al., 2010). Despite the extensive study of tau in synaptic dysfunction in AD models, it is still unknown whether tau mislocalization to dendritic spines can be caused by either a detrimental amyloid precursor protein (APP) mutation or exposure to pathological Aβ species.

Synthetic Aβ1-42 peptides inhibit long-term potentiation and induce the internalization of NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptors (Chen et al., 2002; Snyder et al., 2005; Hsieh et al., 2006; Shankar et al., 2007). It is proposed that soluble Aβ oligomers including Aβ*56, dimers and trimers are responsible for deficits in learning and memory in AD models (Cleary et al., 2005; Lesné et al., 2006; Shankar et al., 2008; Zahs & Ashe, 2013).

To better understand the relationship between Aβ, tau and synaptic deficits we investigated phosphorylation-dependent tau mislocalization in neurons exposed to soluble Aβ oligomers as well as in neurons cultured from transgenic mice expressing APP with the Swedish double mutation (APPSwe mice). Using whole-cell voltage-clamp electrophysiology we explored the mechanistic relationship between Aβ and tau phosphorylation in calcineurin-mediated synaptic dysfunction. Finally, we explored whether P301L tau-induced deficits in AMPAR clustering depend upon calcineurin activity.

Materials and methods

High-density neuronal cultures and neuronal transfection

A 25-mm glass polylysine-coated coverslip (thickness, 0.08 mm) was glued to the bottom of a 35-mm culture dish with a 22-mm hole using silicone sealant as previously described (Wiens et al., 2005). Dissociated neuronal cultures from rat hippocampi at postnatal days 1–2 were prepared as previously described (Liao et al., 2001). Neurons were plated onto prepared 35-mm culture dishes at a density of 1 × 06 cells per dish. The age of cultured neurons was counted from the day of plating as 1 day in vitro (DIV). All experiments were performed on neurons from at least three independent cultures. Neurons at 7–10 DIV were transfected with appropriate plasmids using the standard calcium phosphate precipitation method as previously described (Wiens et al., 2005). After transfection, neurons were returned to a tissue culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) and allowed to mature and develop until 3 weeks in vitro, a time at which neurons express high numbers of dendritic spines with mature morphologies.

Low-density neuronal cultures

To detect the distribution of endogenous synaptic proteins with high resolution, low-density neuronal cultures were prepared as previously described with some modifications (Hoover et al., 2010). Dissociated neuronal cultures from rat hippocampi at postnatal days 1–2 were plated into 12-well culture plates at a density of 50 000–100,000 cells per well. Each well contained a polylysine-coated 12-mm glass coverslip on the bottom. To maintain the low-density cultures for a long time (up to 1 month), the above 12-mm coverslips with low-density cultured neurons were transferred to 60-mm dishes (four coverslips per dish; the coverslips faced up) that contained high-density neuronal cultures after 1 week in vitro. In previous studies, dishes with a glial feed layer were often used to support low-density cultures. Recently, we have found that high-density neuronal cultures are far better supporters than pure glial cells.

Neuronal mouse cultures

Following the protocol described in Strasser et al. (2004), hippocampal cultures were prepared from APPSwe, P301L tau and S845A GluA1-transgenenic mice, respectively (Hsiao et al., 1996; He et al., 2011; Hoover et al., 2010). For primary hippocampal neuron cultures, ~ 1.5 × 104 cells were plated on sets of 5 × 12-mm coverslips that had been previously coated with poly-D-lysine (100 mg/ml) and laminin (4 mg/ml) in neuronal plating media (MEM with Earle’s salts: in mM, HEPES, 10; sodium pyruvate, 10; glutamine, 0.5; and glutamate, 12.5; with 10% FBS and 0.6% glucose). Each set of five coverslips was maintained in a 35-mm dish and each dish corresponded to one mouse. Approximately four hours after plating, the medium was replaced with neuronal growth medium (neurobasal media with B27 supplement, 0.5 mM glutamine) that had been conditioned on glia for 24–48 hours prior to use. Mice were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail-snip lysates using transgene-specific primers.

Electrophysiology

Miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs) were recorded using the pCLAMP (Axon Instruments) software suite from cultured dissociated rat hippocampal neurons at 21–25 DIV with a glass pipette (resistance of ~5MΩ) at holding potentials of −55 mV and filtered at 1 kHz with an output gain, α, of 1 as previously described (Liao et al., 2005). Input and series resistances were checked before and after the recording of mEPSCs, which lasted 5–20 min. There were no significant difference in the series resistances and input resistances amongst the various groups of experiments. Neurons were bathed in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at room temperature (25°C) with 100 μM APV (an NMDAR antagonist), 1 μM TTX (a sodium channel blocker) and 100 μM picrotoxin (GABAa receptor antagonist), gassed with 95% O2–5% CO2. The ACSF contained (in mM): NaCl, 119; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 5.0; MgCl2, 2.5; NaHCO3, 26.2; NaH2PO4, 1; and glucose, 11. The internal solution in the patch pipette contained (in mM): cesium gluconate, 100; EGTA, 0.2; MgCl2, 0.5; ATP, 2; GTP, 0.3; and HEPES, 40 (pH 7.2 with CsOH). All mEPSCs were analyzed with the MiniAnalysis program designed by Synaptosoft Inc. A minimum peak amplitude of 3 pA was set as the detection criterion for mEPSCs. Each mEPSC event was visually inspected and only events with a distinctly fast rising phase and a slow decaying phase were accepted. The frequency and amplitude of all accepted mEPSCs were directly read out using the analysis function in the MiniAnalysis program. Individual events were used for relative cumulative frequency analyses, and averaged parameters from each neuron were treated as single samples in any further statistical analyses.

Time-lapse live imaging method

To label dendrites, high-density neurons were transfected at 7–10 DIV with plasmids encoding enhanced green-fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged molecules, and/or DsRed. The 35-mm culture dishes fit tightly in a custom holding chamber on a fixed platform above an inverted Nikon microscope sitting on an X–Y translation stage (Burleigh Inc.). A 60× oil-immersion lens was used for all imaging experiments. Original images were 157.3 μm wide (x-axis) and 117.5 μm tall (y-axis). The z-axis was composed of 15 images, taken at 0.5-μm intervals. The location of any neuron of interest was recorded by the reading of the X–Y translation stage. The culture dish was immediately put back into a tissue culture incubator after each observation. Neurons could be found again in the next observation using the X–Y translation stage (accuracy, 4 μm).

Immunocytochemistry in fixed tissues

Cultured neurons were fixed and permeabilized successively with 4% paraformaldehyde, 100% methanol and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Hoover et al., 2010). All immunocytochemistry primary and secondary antibodies were diluted by a factor of 1:50 in 10% donkey serum in PBS. Commercial antibodies against PSD-95 were used as a postsynaptic marker (rabbit polyclonal, Invitrogen; mouse monoclonal, Millipore)(Liao et al., 2001). The rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the N-terminus of GluA1 subunits were generated by Dr Richard Huganir’s laboratory. FITC (green)- or rhodamine (red)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used to recognize these primary antibodies.

To estimate the amount of glutamate receptors in dendritic spines, fixed rat neurons immunoreactive for PSD95 (mouse monoclonal; Millipore) and N-GluA were photographed and processed with MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Co.) as previously described (Hoover et al., 2010). Then, immunoreactive clusters of PSD95 were autoselected using the MetaMorph software and the location of these clusters was transferred to images displaying glutamate receptor immunoreactivity on the same neuron. PSD95 immunoreactivity was used to identify dendritic spines. A cursor was placed in the center of the glutamate receptor clusters in dendritic spines to estimate glutamate receptor immunoreactivity as fluorescent pixel intensity in the spines (value Y1). Another cursor was placed in an adjacent dendritic shaft to measure glutamate receptor fluorescent pixel intensity (value Y2) and the ratio of glutamate receptor immunoreactive fluorescence intensity in spines/dendrites (Y1/Y2) was used as the metric for GluA1 content in spines.

Image analysis

Time-lapse live images from the same neuron at 21 DIV were taken before and at various time points after drug treatments as previously described (Liao et al., 2005). All digital images were analyzed with the MetaMorph Imaging System. Unless stated otherwise, all images of live neurons were taken as stacks and were averaged into one image before further analysis. To average, stacks of images were processed by deconvolution of nearest planes using MetaMorph. A stack of deconvolved images was then averaged into a single image. A dendritic protrusion with an expanded head that was 50% wider than its neck was defined as a spine. The number of spines from a dendrite was manually counted and normalized per 100 μM dendritic length; only dendrites with 50 μM or more of analyzable dendritic shaft were counted.

Constructs and pharmacological inhibitor

The enhanced GFP-tagged tau and DsRed constructs (Clontech, Inc.) were expressed in the pRK5 vector and driven by a cytomegalovirusd promoter. All tau constructs were tagged with GFP on the N-terminus. The wild-type (WT) tau construct encoded human four-repeat tau lacking the N-terminal sequences and contained exons 1, 4, 5, 7, 9–13 and 14, and intron 13. Using WT tau as a template, a tau construct termed AP was generated by mutating all 14 proline (P)-directed serine (S) and threonine (T) kinase phosphorylation site (S/P and T/P) amino acid residues (T111, T153, T175, T181, S199, S202, T205, T212, T217, T231, S235, S396, S404 and S422; numbering based on the longest 441-amino-acid brain isoform of htau) to alanine (Mandelkow et al., 1995; Fulga et al., 2006). The PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis was confirmed by sequencing.

One micromolar tacrolimus (FK506) or equivalent volume of DMSO (vehicle) was used to pharmacologically inhibit calcineurin in cultured neurons (Lieberman & Mody, 1994; Kam et al., 2010). FK506 was added alone or together with Aβ oligomers to the culture media at 19–21 DIV and remained for the length of the experiments.

Oligomerized Aβ1-42 preparation

Synthetic Aβ1-42 was prepared as previously described (Lambert et al., 2001; Stine et al., 2003; Hepler et al., 2006; Shughrue et al., 2010) with some modification. Aβ1-42 was a product of Sigma Aldrich Corporation (A9810; 0.1mg) and was purchased in 0.1-mg aliquots. Aβ1-42 was suspended in ~22.17 μL of 1,1,1,3,3,3,hexafluoro-2-propanol. After suspension, Aβ1-42 was incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes and dried using a SpeedVac for 1 h at 30°C. Aβ1-42 was resuspended in DMSO to create a 5-mM concentration. Resuspended Aβ1-42 was water-bath-sonicated for 10 min. After sonication, F-12 solution was added to the Aβ1-42-DMSO suspension to create a final concentration of 100 μM. Aβ1-42 was incubated at 4° C for 14 days. After 14 days, a Western blot was performed to verify oligomerization of Aβ1-42. Cells were treated with 2 μM oligomerized Aβ1-42, or the equivalent volume of F-12 solution as control (vehicle).

Western blots were used to confirm the presence of dimeric, trimeric and high-order species within oligomerized Aβ1-42. Oligomerized Aβ1-42 Western blots were performed in Dr Karen Ashe’s laboratory as previously described by Lesné et al. 2006. Oligomerized Aβ1-42 samples were diluted 1:1000 in IP dilution buffer (IPDB). IPDB was made by adding 50 mL of 1M Tris-HCL and 8.76g NaCl to 1L of water. Fifty microlitres of protein G sepharose B Flat Flow beads were added to each sample. Suspensions were incubated for 1 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 9200g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and 5 μg of 6E10 antibodies (1:2500) were added to each sample and suspended overnight. Samples were washed using IP buffer A and IP buffer B. IP buffer A contained 50 mL of 1M Tris-HCL, 1 mL of Triton X-100, 17.52g NaCl and 0.372g EDTA. IP buffer B contained 50 mL of 1M Tris-HCL, 1 mL of Triton X-100, 8.76g NaCl, and 0.372g EDTA. Samples of oligomerized Aβ1-42 were eluted using IPDB and loading buffer.

To run Western blots, 2μg of oligomerized Aβ1-42 were aliquoted and resuspended in tricine buffer and size-fractioned by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) using pre-cast 10% SDS Tris-Tricine gels. Gels were blotted using nitrocellulose membranes that were boiled twice in 50 mL PBS. Membranes were blocked in Tri-buffered saline 0.1% containing 5% bovine serum for 2 hours at room temperature and then probed with blocking buffer. Primary antibodies were detected with anti-IgG immunoglobulins conjugated with either biotin or horseradish peroxidase. Before cells were treated with oligomerized Aβ1-42, samples were verified to ensure content of toxic oligomeric dimers and trimers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using PRISM4 (GraphPad). Two-sample comparisons were made using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Multiple comparisons were made using ANOVA: for lime-lapse imaging we used repeated-measures two-way ANOVA and for all other analyses we utilized regular two-way ANOVA. Post hoc analysis was performed using Bonferroni post-tests. Post hoc tests were only utilized when significant variance was found (P < 0.05), to limit the possibility of an error of the first type. Comparison of the normal region of relative cumulative frequencies was made using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test (http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/KS-test.n.plot_form.html). P < 0.05 was considered significant. All mean data are reported with SEM.

Results

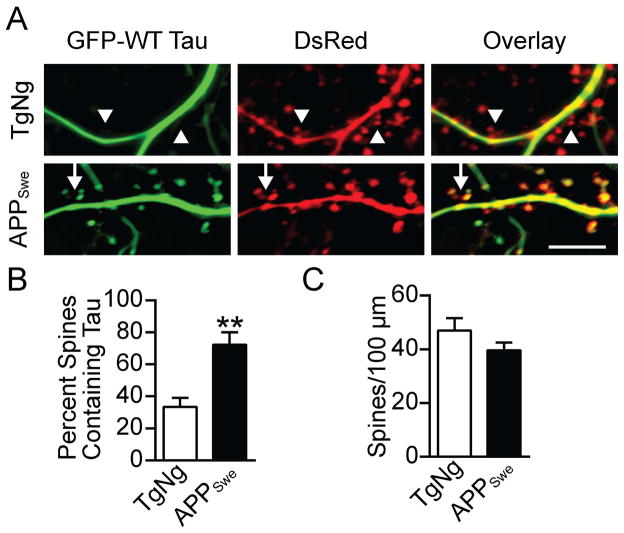

Tau was mislocalized to dendritic spines in neurons cultured from APPSwe-transgenenic mice

Early-onset familial AD is associated with the Swedish mutation at APP 670/671 (Citron et al., 1992; Mullan et al., 1992). The APPSwe mice, which express APP with Lys670Asn and Met671Leu mutations (also referred to as Tg2576), have previously been shown to have high levels of soluble Aβ oligomers that correlate with cognitive deficits (Hsiao et al., 1996; Lesné et al., 2006). To test our hypothesis that tau mislocalizes to spines in neurons from APPSwe mice, we cultured hippocampal neurons from APPSwe mice and their transgenic-negative (TgNg) littermates. We then transfected the neurons with GFP-tagged WT tau DsRed at 7–10 DIV and imaged them at 21–24 DIV (Figure 1A). The GFP-tagged tau allowed us to determine the subcellular localization of tau, while the DsRed freely diffused throughout the neurons and revealed their morphology. Next, we determined the proportion of spines containing tau. We found that tau mislocalized to the dendritic spines of APPSwe mice in a significantly greater proportion than in the spines of TgNg neurons (n = 5, t = 4.02, P < 0.01, Student’s t-test; Figure 1B). No significant differences in spine density were found between groups (Figure 1C). These results demonstrate that tau mislocalization occurs in neurons cultured from transgenic mice that express an APP mutation found in humans with AD.

Figure 1.

WT Tau is mislocalized to dendritic spines in hippocampal neurons cultured from APPSwe-transgenenic mice. (A) Representative images of hippocampal neurons cultured from TgNg or APPSwe-transgenenic mice and then transfected with GFP-WT tau and DsRed. Images were taken at 21 DIV. Arrows indicate spines that contain tau, arrowheads indicate spines lacking tau. (B) Quantification of dendritic spines containing tau. This proportion is generated by dividing the number of spines containing tau by the total spine count. Tau is found in a significantly greater proportion of spines in neurons from APPSwe mice than TgNg mice. (C) Quantification of spine density as calculated by visual inspection of DsRed fluorescence. No significant difference was found in spine density between groups. Student’s t-test, **P < 0.01. Scale bar, 10 μm.

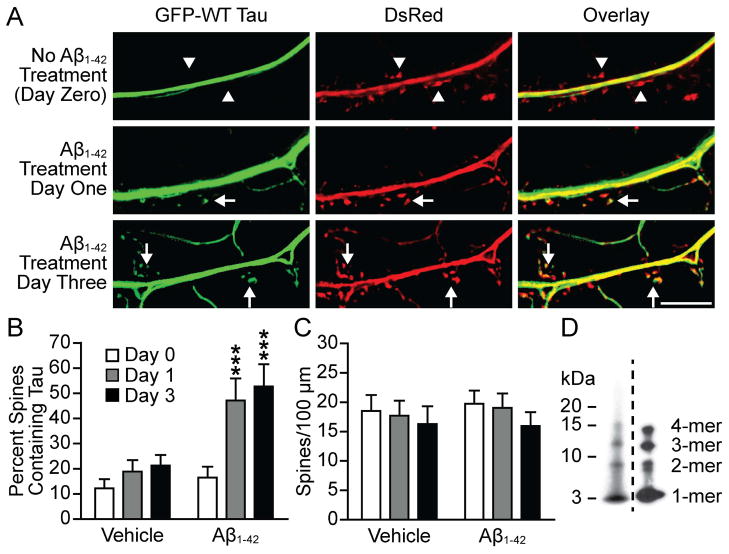

Oligomerized Aβ1-42 caused the mislocalization of tau to dendritic spines

The above observation that mislocalization of tau to spines occurs in neurons from APPSwe-transgenenic mice led us to hypothesize that soluble Aβ1-42 oligomers are responsible for the mislocalization. We prepared synthetic Aβ1-42 oligomers using a previously described protocol (Lambert et al., 2001; Hepler et al., 2006; Shughrue et al., 2010). Our oligomerized synthetic Aβ1-42 consistently contained dimers, trimers and tetramers as measured by Western blot (Figure 2d). The localization of tau was investigated by first transfecting cultured hippocampal neurons at 7–10 DIV with GFP-tagged WT tau and DsRed. At 21 DIV we took live images of the neurons and then treated the dishes with vehicle or oligomerized Aβ1-42 (2 μM). The vehicle group was treated with F12 (the solvent oligomerized Aβ1-42 is prepared in) as a control. We next imaged the same neurons 1 and 3 days after treatment (Figure 2B). Prior to oligomerized Aβ1-42 treatment WT tau was expressed in the dendrites and very minimally in the dendritic spines. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA detected significant changes amongst factors (F2,44 = 14.38; F1,22 = 7.97; F2,44 = 5.42; P < 0.01). Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that the proportion of spines containing tau was increased significantly 1 day (t = 5.01) and 3 days (t = 5.94) after treatment (n = 11–13, P < 0.001; Figure 2B). No significant changes were detected in the vehicle-treated group. Spine density was not significantly changed in either group (Figure 2C). These results signify that exogenous synthetic Aβ1-42 causes tau mislocalization in cultured hippocampal neurons.

Figure 2.

WT tau is mislocalized to dendritic spines in neurons treated with oligomerized Aβ1-42. (A) Representative images from cultured hippocampal neurons transfected with GFP-WT tau and DsRed. Images were taken at 21 DIV, before Aβ1-42 treatment, and then 1 and 3 days after treatment. Arrows indicate spines that contain tau, arrowheads indicate spines lacking tau. (B) Quantification of spines containing tau. This proportion was calculated by dividing the number of spines containing tau by the total spine count. Tau presence in spines was significantly increased after treatment with Aβ1-42. Treatment with vehicle led to no significant changes. (C) Quantification of spine density. No significant differences were found between groups. (D) Composite of Western blots showing two examples of oligomerized synthetic Aβ1-42 preparations. Toxic Aβ species including dimers, trimers and tetramers were consistently found in our preparations. However, no Aβ*56 is detected, suggesting that low-order oligomers might be sufficient to induce synaptic deficits. Repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 10 μm.

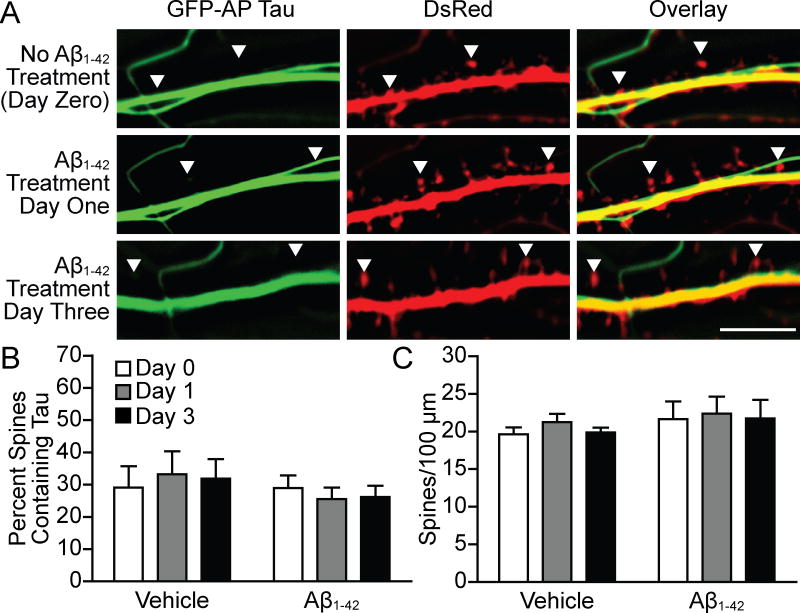

Phosphorylation activity of tau was necessary for oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced tau mislocalization

We next designed an experiment to test the role of tau phosphorylation in oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced mislocalization of tau to dendritic spines. We employed a tau construct, known as AP tau, in which the 14 S and T residues that can be phosphorylated by P-directed S or T kinases (SP or TP) were mutated to alanine in order to prevent phosphorylation (Fulga et al., 2007; Hoover et al., 2010). Similarly to the last experiment, we transfected cultured hippocampal neurons at 7–10 DIV with GFP-tagged AP tau and DsRed. We then took live images of the neurons at 21 DIV and treated with vehicle or oligomerized Aβ1-42. The same neurons were then imaged 1 and 3 days after treatment (Figure 3A). We found no change in the proportion of spines containing tau in neurons transfected with AP tau and treated with oligomerized Aβ1-42 (n = 6 vehicle and 13 Aβ1-42; Figure 3B). No significant changes were detected in the vehicle group. There were no significant changes in dendritic spine density at the time points measured for vehicle or oligomerized Aβ1-42 treated groups (Figure 3C). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the proportion of spines that contained AP and wild-type tau proteins versus the total number of spines in control groups treated with the vehicle solution (comparison between Figures 2 and 3). This experiment indicates that tau phosphorylation at 14 P-directed S or T residues is necessary for oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced tau mislocalization.

Figure 3.

AP tau was not mislocalized to dendritic spines in neurons treated with Aβ1-42. (A) Representative images from cultured hippocampal neurons transfected with GFP-AP tau and DsRed. Images were taken at 21 DIV, before Aβ1-42 treatment, and then 1 and 3 days after treatment. (B) Quantification of spines containing tau. This proportion was calculated by dividing the number of spines containing tau by the total spine count. AP tau presence in spines did not change significantly after treatment with Aβ1-42. The dominant negative AP tau would probably block the mislocalization of endogenous tau. Treatment with vehicle also led to no significant changes. (C) Quantification of spine density. No significant differences were found between groups. Repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test. Scale bar, 10 μm.

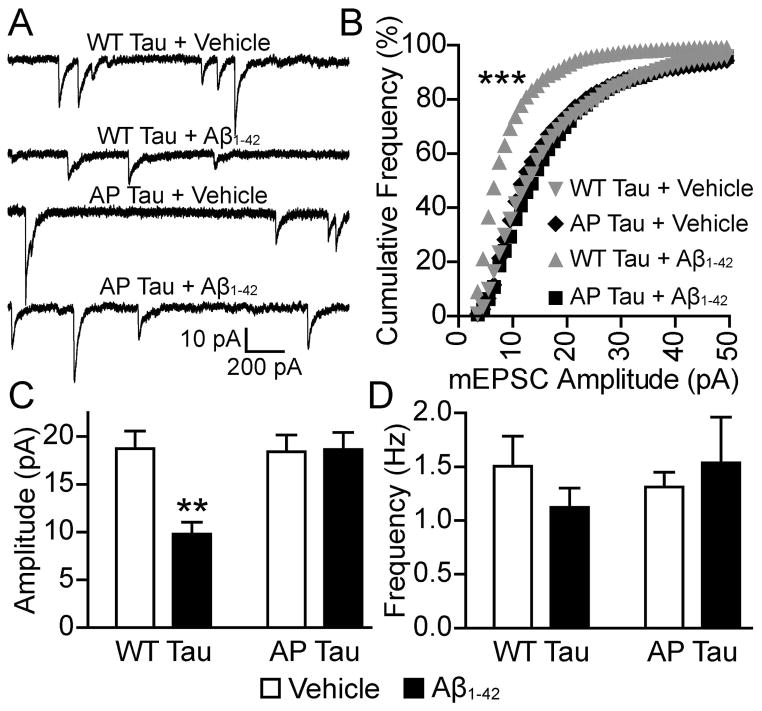

Oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced AMPAR signaling deficits required phosphorylation of tau

We have previously shown that phosphorylation-dependent tau mislocalization to dendritic spines is correlated with synaptic dysfunction (Hoover et al., 2010). To determine whether the observed Aβ-induced tau mislocalization in the present study also correlates with synaptic deficits, and to determine whether tau phosphorylation is necessary for deficits, we transfected neurons with WT tau or AP tau tagged with GFP at 7–10 DIV. After 3 weeks in vitro, we then treated the neurons with Aβ1-42 oligomers or vehicle. After 3 days of drug treatment we recorded AMPAR-mediated mEPSCs from the transfected neurons (Figure 4). AMPAR-mediated mEPSCs represent postsynaptic responses to a spontaneously-released vesicle at a single dendritic spine. In neurons expressing WT tau, treatment with Aβ1-42 significantly decreased the mEPSC amplitude compared with control vehicle-treated neurons (n=10, D = 0.46, P < 0.001, KS-test; Figure 4B). There was no significant difference between treatment groups in neurons expressing AP tau, indicating that tau phosphorylation is required for the effects of Aβ. Two-way ANOVA detected significant variance amongst groups (F1,36 = 6.46; F1,36 = 6.69; F1,36 = 7.43; P < 0.05). Consistent with the KS-test, Bonferroni post-tests showed that Aβ treatment significantly decreased mEPSC amplitude in neurons expressing WT tau but not in neurons expressing AP tau (n = 10, t = 3.76, P < 0.01; Figure 4C). The frequency of AMPAR-mediated mEPSCs was not significantly different between groups. Two conclusions can be deduced from these results: (i) Aβ1-42 oligomers decrease AMPAR signaling in neurons transfected with WT tau; and (ii) tau phosphorylation at S/P and T/P phosphorylation sites is necessary for Aβ1-42 oligomer-induced deficits.

Figure 4.

Aβ1-42 treatment led to a decrease in AMPAR mEPSC amplitude that was dependent upon tau SP/TP phosphorylation. (A) Representative traces of AMPAR mEPSCs recorded from cultured hippocampal neurons treated with WT tau or AP tau and treated with vehicle or Aβ1-42. (B) Cumulative frequency distributions of mEPSC amplitudes from the groups represented in A. Neurons expressing WT tau, treated with Aβ1-42, had significantly more small mEPSCs than neurons from the other three groups. Bin size, 1 pA. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, ***P < 0.001. (C) Mean mEPSC amplitude of groups represented in A. The mean amplitude of mEPSCs from Aβ1-42-treated neurons expressing WT tau was significantly lower than those from the other three groups. (D) Mean mEPSC frequency of groups represented in A. No significant differences were found between groups. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test, **P < 0.01.

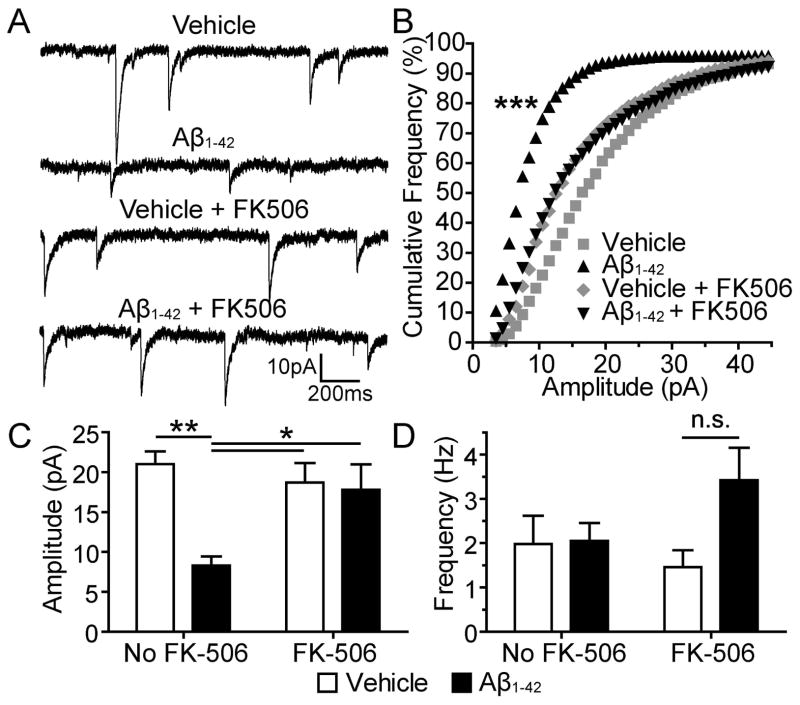

Oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced AMPAR signaling deficits required calcineurin activity

We next sought to investigate signaling mechanisms that mediate oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced AMPAR signaling deficits downstream of tau. Calcineurin plays an important role in AMPAR dynamics and is implicated in long-term depression of hippocampal synapses (Mulkey et al., 1994; Dell’Acqua et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2012). To determine the role of calcineurin in oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced AMPAR signaling deficits we treated the neurons with FK506, an inhibitor of calcineurin (Lieberman & Mody, 1994). At 19–22 DIV we treated cultured hippocampal neurons with vehicle alone, vehicle + FK506, oligomerized Aβ1-42 alone, or oligomerized Aβ1-42 + FK506. After 3 days of drug treatment we recorded AMPAR mEPSCs from the cultured neurons (Figure 5). Neurons treated with oligomerized Aβ1-42 had significantly smaller mEPSC amplitudes than those treated with vehicle alone (n = 10, D = 0.37, P < 0.001, KS-test). There was no significant difference between vehicle + FK506 and oligomerized Aβ1-42 + FK506 groups (Figure 5B), indicating that FK506 blocked the effect of Aβ. Two-way ANOVA detected significant changes amongst the treatment groups (F1,36 = 9.33, P = 0.004; F1,36 = 7.01, P = 0.012). Consistent with the KS-test, Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that Aβ treatment significantly decreased mEPSC amplitudes (n = 10, t = 4.03, P < 0.01) and FK506 blocked this effect (n =10, t = 3.00, P < 0.05; Figure 5C). There were no significant differences in mEPSC frequency between groups (Figure 5D). These results indicate that calcineurin activity is necessary for oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced AMPAR signaling deficits. Notably, the neurons in this experiment did not express human WT tau, suggesting that Aβ1-42 oligomers cause synaptic deficits in rat neurons by acting upon endogenous tau.

Figure 5.

Aβ1-42 treatment leads to a decrease in AMPAR mEPSC amplitude that is dependent upon calcineurin activity. (A) Representative traces of AMPAR mEPSCs recorded from cultured hippocampal neurons treated with vehicle, Aβ1-42, vehicle + FK506, or Aβ1-42 + FK506. (B) Cumulative frequency distributions of mEPSC amplitudes of groups represented in A. Neurons treated with Aβ1-42 had significantly more small mEPSCs than neurons from the other three groups. Bin size, 1 pA. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, ***P < 0.001. (C) Mean mEPSC amplitude of groups represented in A. The mean amplitude of mEPSCs from Aβ1-42-treated neurons was significantly lower than those from the other three groups. (D) Mean mEPSC frequency of groups represented in A. No significant differences were found between groups. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

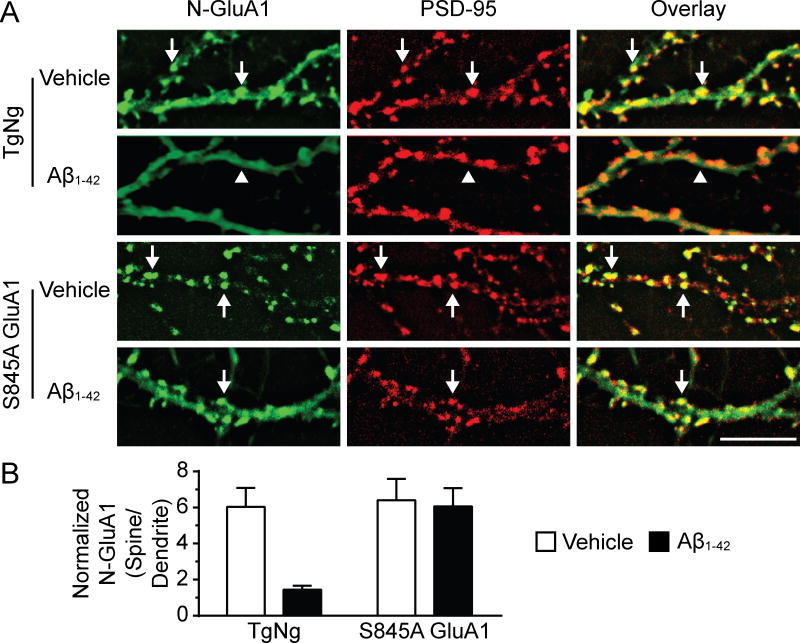

Oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced internalization of the GluA1 AMPAR subunit required activity at GluA1 S845

Calcineurin has been shown to dephosphorylate GluA1 AMPAR subunit residue S845 in cellular models that induce AMPAR internalization (Lee et al., 1998; Kam et al., 2010). We sought to determine whether this GluA1 residue is necessary for calcineurin-dependent loss of AMPAR induced by oligomerized Aβ1-42. To investigate this hypothesis we cultured hippocampal neurons from knock-in mice expressing GluA1 S845A (which renders the residue impervious to the effects of kinases and phosphatases) and their TgNg littermates (He et al., 2011). We allowed the neurons to mature in the dish and then treated them with vehicle or oligomerized Aβ1-42 at 21 DIV. After 3 days of exposure, neurons were stained with an antibody to N-GluA1 (recognizing the extracellular domain at the N-terminus of GluA1 subunits) to detect surface AMPARs using a protocol as previously described (Liao et al., 1999). We next fixed and permeablized the membranes of the neurons and stained with an antibody to PSD-95 (Figure 6A). Two-way ANOVA detected significant differences between the multiple factors (F1,36 = 0.01; F1,36 = 0.01; F1,36 = 0.03; P < 0.05). Oligomerized Aβ1-42 significantly decreased the expression of surface GluA1; this effect was abolished in neurons cultured from S845A knock-in mice (n = 10, t = 3.42, P < 0.01; Bonferroni post-tests; Figure 6B). In our previous study (Kam et al., 2010), surprisingly, the phosphorylation-mimicking mutation S845D acts similarly to the phosphorylation-blocking S845A mutation in opioid-induced AMPAR internalization, suggesting that the acute dephosphorylation event is more important than the static phosphorylation status at S845 of GluA1. Our current findings suggest that decreases in the amplitude of AMPAR currents found after treatment with oligomerized Aβ1-42 are due to internalization of GluA1 AMPAR subunits. Furthermore, changes in the phosphorylation state of S845 of GluA1 are involved in oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced loss of GluA1 AMPAR subunits.

Figure 6.

Aβ1-42 treatment led to the internalization of dendritic spine GluA1 AMPAR subunits in a manner that was dependent upon GluA1 S845 activity. (A) Representative images of hippocampal neurons cultured from TgNg and S845A GluA1 knock-in mice and stained with antibodies to N-GluA1 (green) and PSD-95 (red). At 21 DIV neurons were treated with vehicle or Aβ1-42 and imaged after 3 days. Arrows indicate GluA1 clusters co-localized with PSD-95 clusters; arrowheads indicate diffuse staining of GluA1 in the dendritic shafts. (B) Quantification of N-GluA1 expression in groups represented in A. Fluorescence intensity of the green channel was measured at individual dendritic spines and adjacent dendritic shafts. Spine intensity was then normalized to dendrite intensity for each spine. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test, **P < 0.01. Scale bar, 10 μm.

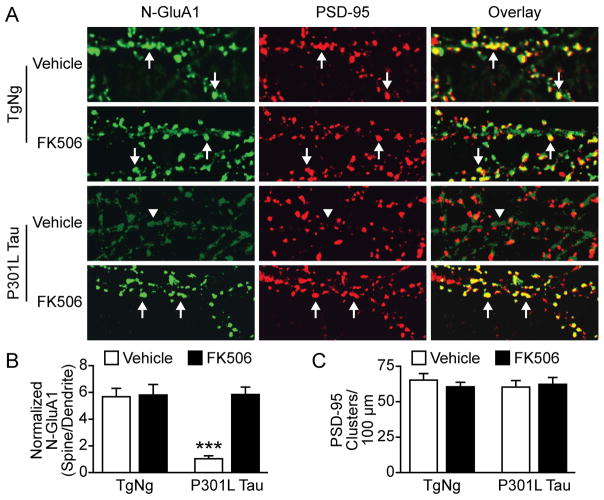

Calcineurin-dependent AMPAR internalization could also be induced by changes in tau alone

Consistent with the previous study by Hsieh et al. (2006), we found that Aβ oligomers cause calcineurin-dependent AMPAR internalization. However, it is unknown whether changes in tau alone can activate this signaling pathway. We cultured dissociated hippocampal neurons from TgNg mice and transgenic mice expressing P301L tau proteins (Figure 7). At 14–16 DIV neurons were treated with FK506 or vehicle. Live neurons were incubated with anti-N-GluA1 antibodies at 21 DIV and then fixed and permeabilized for PSD-95 staining and imaging (Liao et al., 1999; Figure 7A). Two-way ANOVA detected a significant difference in the multiple factors (F1,36 = 16.18; F1,36 = 18.81; F1,36 = 16.61, P < 0.001). The expression of P301L tau significantly reduced the amount of surface AMPARs on dendritic spines whereas treatment with FK506 rescued this deficit (n = 10, t = 5.73, P < 0.001, Bonferroni post-test; Figure 7B). There was no significant difference in PSD-95 clusters among the above four groups, suggesting spine loss may occur at future time-points (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

FK506 rescued the disruption of surface AMPAR clustering caused by P301L tau. (A) Representative images of hippocampal neurons cultured from TgNg mice and transgenic mice expressing P301L tau proteins. The neurons were stained with antibodies to N-GluA1 (green) and PSD-95 (red). At 14–16 DIV neurons were treated with FK506 or DMSO (vehicle) and imaged at 21 DIV. Arrows indicate GluA1 clusters co-localized with PSD-95 clusters; arrowheads indicate diffuse staining of GluA1 in the dendritic shafts. (B) Quantification of N-GluA1 expression in four groups in A. Fluorescent intensity of the green channel was measured at individual dendritic spines and adjacent dendritic shafts. (C) There was no significant difference in the density of spines detected by anti-PSD-95 antibody. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test, n=10 neurons per group, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

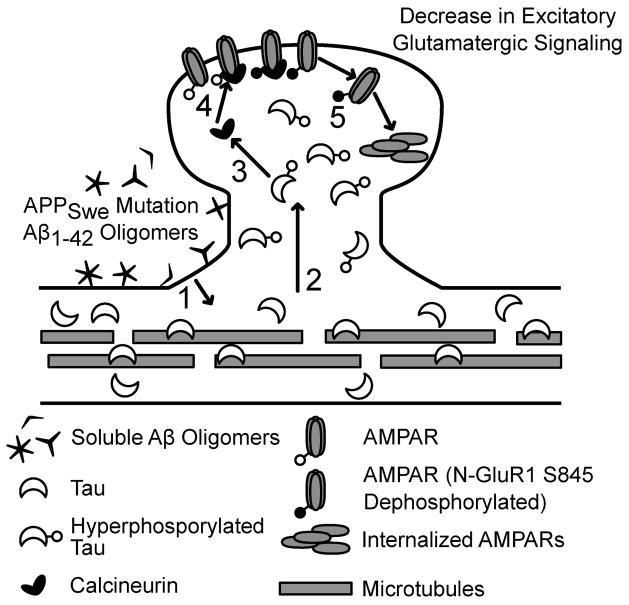

The cornerstone of the Aβ cascade hypothesis is that amyloid pathology occurs upstream of neurodegeneration mediated by tau (Reitz, 2012). However, in an early model of the amyloid cascade hypothesis, Aβ-induced synaptic deficits occur before, or tangentially to, tau phosphorylation and tau pathologies (Hardy & Higgins, 1992; Hardy & Selkoe, 2002). Our results support an updated amyloid beta cascade hypothesis, showing that tau phosphorylation-mediated mislocalization and synaptic deficits are downstream of Aβ1-42 oligomer initiation of the cascade (Figure 8). Furthermore, evidence from this study suggests that calcineurin may play a role in AMPAR internalization downstream of tau.

Figure 8.

Proposed pathway for soluble Aβ1-42 oligomer-induced plasticity at dendritic spines. (1) Treatment with Aβ1-42 leads to tau hyperphosphorylation. (2) Tau mislocalizes to dendritic spines after Aβ initiation. The ratio of tau proteins bound to microtubules versus unbound tau proteins in the dendritic shaft before Aβ initiation is unknown. (3) Mislocalized tau provokes activation of calcineurin. (4) Activated calcineurin dephosphorylates AMPAR GluA1 subunit residue S845. (5) AMPAR receptors are internalized.

The role of tau mislocalization to dendritic spines in AD

Our group’s previous study first reported the mislocalization of tau to dendritic spines in transgenic mice modeling frontotemporal dementia (Hoover et al., 2010). Our findings built on observations that tau mislocalizes to the somatodendritic compartment of neurons in AD-transgenic mice (Ittner et al., 2010; Zempel et al., 2010), but we critically advanced this notion by showing that tau mislocalization does not stop at the dendrite but continues into spines. We found that tauP301L-transgenenic mice exhibit cognitive deficits that correlate with the mislocalization of tau to dendritic spines (Hoover et al., 2010). The present report extends our previous findings by demonstrating that tau mislocalization occurs in the presence of increased levels of soluble Aβ1-42 oligomers in the absence of tau mutation. We show that tau mislocalization occurs in neurons from APPSwe-transgenenic mice and in neurons exposed to synthetic oligomerized Aβ1-42 (Figures 1 & 2). This data supports models of the amyloid cascade hypothesis, putting APP mutation and increase in extracellular Aβ1-42 oligomers upstream of tau pathology (Hardy & Higgins, 1992; Hardy & Selkoe, 2002). The implications of tau’s presence in dendritic spines are vast as most excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission in the brain occurs in dendritic spines (Cingolani & Goda, 2008; Patterson & Yasuda, 2011). Dendritic spines are specialized structures in which protein signaling is compartmentalized by their long thin necks and the binding properties of anchoring proteins localized to their heads (Bloodgood & Sabatini, 2005; Byrne et al., 2011). When tau enters a spine it is exposed to a cornucopia of proteins that serve functions in plasticity, proteins that gate the entry of Ca2+ into the spine, proteins that control the expression and dynamics of glutamate receptors, and numerous anchoring proteins (Malenka & Bear, 2004; Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2009). We hypothesize that the entry of tau into dendritic spines underlies the early stages of the disease process in AD.

Fyn, AMPK and Spastin have been implicated in synaptic deficits found in AD (Zempel et al., 2013; Laurén, 2014). In contrast to our studies, the activation of the above pathways causes significant loss of dendritic spines at some stage. Interestingly, it has been shown that Aβ oligomers cause transient spine collapse within hours of treatment but the density of spines returns to normal after 12 hours (Zempel et al., 2013). Unsurprisingly, no significant change in spine density was detected in our experimental system. This research is not inconsistent with studies which also find permanent spine loss after extracellular Aβ treatment in excess of 5 days (Hsieh et al., 2006; Sheng et al., 2012). Neurons in the brains of AD patients are exposed to high levels of toxic Aβ species for years. Our study has unraveled a new aspect of synaptic deficits: the functions of the spines can be compromised even if permanent spine loss has not yet occurred.

Phosphorylation of tau is critical for oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced tau mislocalization and synaptic deficits

Although the phenomenon of tau phosphorylation in AD and other dementias has been widely reported (Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986; Mucke et al., 2000; Avila et al., 2004; Buerger et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2013), evidence of a mechanistic role of tau phosphorylation in synaptic deficits found in AD models has been scarce (Steinhilb et al., 2007; Hoover et al., 2010). Reports suggest that soluble Aβ induces tau phosphorylation (Takashima et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1998); additionally, phosphorylation of tau by P-directed kinases regulates the microtubule-binding activity of tau (Alonso et al., 1994; Wang et al., 1998). In our past exploration of tau mislocalization in neurons expressing P301L tau we were able to manipulate the phosphorylation of tau by co-expressing AP tau. We showed that phosphorylation of tau at SP/TP residues is necessary for both the mislocalization of tau and decreases in AMPAR signaling in neurons expressing the P301L mutation (Hoover et al., 2010). In the current report we have expanded upon those findings by showing that SP/TP phosphorylation of tau is necessary for both oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced tau mislocalization and synaptic deficits (Figures 3 & 4). These results advance our knowledge of the relationship between tau phosphorylation, tau mislocalization and synaptic deficits from frontotemporal dementia to AD. Our data implicates aberrant phosphorylation of tau as a potential target in the treatment of AD and other dementias. Additionally, this adds further evidence of the importance of P-directed S/T kinases, such as glycogen synthase kinase 3 (Hooper et al., 2008), in tau hyperphosporylation found in AD. Our study finds that tau is a mediator of Aβ-induced early synaptic dysfunction.

Calcineurin-mediated AMPAR internalization in oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced synaptic deficits

Although a number of research groups have reported the necessity of calcineurin in cognitive and synaptic deficits found in AD models (Chen et al., 2002; Snyder et al., 2005; Dineley et al., 2007; Abdul et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2010), the role of calcineurin in synaptic deficits caused by extracellular exposure to Aβ oligomers is still unknown. Calcineurin is a phosphatase that has been widely implicated in long-term depression and which shares a number of features with the synaptic deficits found in AD (Mulkey et al., 1993; Dell’Acqua et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2012). In both long-term depression and models of AD, AMPAR currents and spine structure are affected (Zhou et al., 2004; Hsieh et al., 2006; Sheng et al., 2012). Here, we report that the amplitude of AMPAR currents is decreased in a calcineurin-dependent manner when neurons are treated with oligomerized Aβ1-42 (Figure 5). This finding is congruent with past findings demonstrating the importance of calcineurin in synaptotoxicity associated with AD; we add to this body of literature by demonstrating a role for calcineurin early in the disease process. GluA1 S845 has been shown to be dephosphorylated by calcineurin (Lee et al., 1998; Kam et al., 2010). GluA1 S845A prevents oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced GluA1 internalization, suggesting a link between calcineurin and reduced AMPAR signaling (Figure 6). Furthermore, we have shown that P301L tau-induced reductions in surface AMPAR clustering on dendritic spines can be ameliorated by inhibiting calcineurin activity (Figure 7). Taken together these results support our hypothetical model in which tau and calcineurin act downstream of Aβ initiation (see diagram in Figure 8).

Calcineurin is activated by the entry of low concentrations of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm (Dell’Acqua et al., 2006). In models of AD, Ca2+ homeostasis has been proposed to be dysregulated by modulation of NMDA glutamate receptors, L-type Ca2+ channels and/or mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering (Green, 2009). Elevated Aβ levels may lead to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration sufficient to activate calcineurin. (Kuchibhotla et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2010; Zempel et al., 2010). The mislocalization of tau to dendritic spines may initiate a signaling process that leads to the entry of low levels of Ca2+ into the intracellular space. Our findings highlight the significance of tau mislocalization to dendritic spines and further our understanding of the signaling mechanisms that mediate synaptic deficits caused by soluble Aβ oligomers in AD.

Functional deficits probably precede permanent spine loss in oligomerized Aβ1-42-treated neurons

Our results suggest that oligomerized Aβ1-42-induced spine loss is downstream of decreases in AMPAR signaling. Research by Zempel et al. (2013) shows that transient spine loss occurs within the 1–2 hours following Aβ administration; spine density is restored during the subsequent 12 hours. This supports our research which found no appreciable spine loss in the APPSwe mouse model of early AD and in neurons treated with Aβ1-42 oligomers for 1–3 days (Figures 1 and 2). Curiously, after 3 days of oligomerized Aβ1-42 treatment we see decreases in the amplitude, but not the frequency, of AMPAR currents (Figures 4 and 5). Changes in mEPSC amplitude represent an alteration in the AMPAR compliment at the synapse while changes in mEPSC frequency are attributed to modifications in presynaptic release or synapse density. The lack of change in mEPSC frequency of neurons treated with oligomerized Aβ1-42 supports our finding of no change in spine density in our live-imaging experiment.

Most groups investigating spine density after treatment with Aβ oligomers have not seen spine loss until 5 or more days after treatment (Hsieh et al., 2006; Shrestha et al., 2006; Shankar et al., 2007; 2008; Sheng et al., 2012). We suspect that permanent spine loss is the result of longer-term exposure to Aβ oligomers. If this is the case then our research implies that deficits in AMPAR signaling persist after transient spine loss (Zempel et al., 2013) but before permanent spine loss due to longer-term exposure to Aβ oligomers. This hypothesis conforms with basic research into the mechanisms of LTD and LTP, which has indicated that functional changes occur prior to structural changes (Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2009). In slice culture experiments in which APP was overexpressed, protection against AMPAR internalization via mutation of GluA2 residue R845 prevented spine loss in addition to functional deficits (Hsieh et al., 2006). We predict that the GluA1 S845A mutation has a similar effect and protects against spine loss in oligomerized Aβ1-42-treated neurons as well as GluA1 internalization at later time points.

Conclusion

As synaptic deficits caused by Aβ oligomers are blocked by either the expression of AP tau or though pharmacological inhibition of calcineurin with FK506, the present study presents new evidence that tau hyperphosphorylation and calcineurin activation are two intermediate events between Aβ initiation and eventual synaptic deficits, supporting the central premise of the current Aβ cascade hypothesis. Our results from GluA1 S845A knock-in mice provide additional evidence supporting the involvement of calcineurin-mediated AMPAR internalization in the Aβ–tau cascade. Moreover, changes in tau alone can also cause calcineurin-mediated AMPAR internalization in dendritic spines, indicating that Aβ1-42 oligomers and mutant tau share a common, calcineurin-mediated, signaling pathway which leads to synaptic deficits. As neurons in the brains of AD patients are exposed to toxic species of Aβ for years, our experiments with a longer-term Aβ treatment unravel a new aspect of synaptic deficits: the functions of dendritic spines can be compromised in the absence of overt structural impairment.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to Dr Karen Hsiao Ashe for generously providing the transgenic mice expressing APPSwe and for her thoughtful discussion throughout this project. We would like to thank Drs Michael Lee, Sylvain Lesné, Daniel Miller and Brian Hoover for thoughtful discussion, Dr Ben Smith for thoughtful discussion and technical expertise, and Susan Bushek and Samantha Sydow for technical assistance. We would also like to thank our funding sources: NIDA Training Grant T32 DA07234 and Predoctoral Training Grant P32-GM008471 to E.C.M.; and NIDA R01-DA020582, NIDA K02-DA025048, a grant from American Health Assistance Foundation and a grant from Michael J. Fox Foundation to D.L.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AP tau

tau construct generated by mutating all 14 proline-directed kinase, S and T phosphorylation site amino acid residues to alanine

- APP

Aβ precursor protein

- APPSwe mice

transgenic mice expressing APP with the Swedish double mutation

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- DIV

day(s) in vitro

- FK506

tacrolimus

- GFP

green-fluorescent protein

- mEPSC

mini excitatory postsynaptic current

- P

proline

- S

serine

- S/P

P-directed S kinase phosphorylation site amino acid residues

- T

threonine

- T/P

P-directed T kinase phosphorylation site amino acid residues

- TgNg

transgenic-negative

- WT

wild-type

References

- Abdul HM, Sama MA, Furman JL, Mathis DM, Beckett TL, Weidner AM, Patel ES, Baig I, Murphy MP, LeVine H, Kraner SD, Norris CM. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with selective changes in calcineurin/NFAT signaling. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:12957–12969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1064-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso AC, Zaidi T, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Role of abnormally phosphorylated tau in the breakdown of microtubules in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5562–5566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Chakrabarti S, Lee JH, Nakano AH, Dado RJ, Loh HH, Law PY, Wessendorf MW, Elde R. Distribution and targeting of a mu-opioid receptor (MOR1) in brain and spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3328–3341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila J, Lucas JJ, Perez M, Hernandez F. Role of tau protein in both physiological and pathological conditions. Physiological Reviews. 2004;84:361–384. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Kelly JF, Aggarwal NT, Shah RC, Wilson RS. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. 2006;66:1837–1844. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219668.47116.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Arnold SE. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:378–384. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodgood BL, Sabatini BL. Neuronal activity regulates diffusion across the neck of dendritic spines. Science. 2005;310:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.1114816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerger K, Ewers M, Andreasen N, Zinkowski R, Ishiguro K, Vanmechelen E, Teipel SJ, Graz C, Blennow K, Hampel H. Phosphorylated tau predicts rate of cognitive decline in MCI subjects: a comparative CSF study. Neurology. 2005;65:1502–1503. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183284.92920.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne MJ, Waxham MN, Kubota Y. The impacts of geometry and binding on CaMKII diffusion and retention in dendritic spines. J Comput Neurosci. 2011;31:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10827-010-0293-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PF, White GL, Jones MW, Cooper-Blacketer D, Marshall VJ, Irizarry M, Younkin L, Good MA, Bliss TV, Hyman BT, Younkin SG, Hsiao KK. Impaired synaptic plasticity and learning in aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:271–276. doi: 10.1038/6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QS, Wei WZ, Shimahara T, Xie CW. Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide inhibits the late phase of long-term potentiation through calcineurin-dependent mechanisms in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;77:354–371. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani LA, Goda Y. Actin in action: the interplay between the actin cytoskeleton and synaptic efficacy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:344–356. doi: 10.1038/nrn2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung AY, Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lieberburg I, Selkoe DJ. Mutation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer’s disease increases beta-protein production. Nature. 1992;360:672–674. doi: 10.1038/360672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe KH. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies CA, Mann DM, Sumpter PQ, Yates PO. A quantitative morphometric analysis of the neuronal and synaptic content of the frontal and temporal cortex in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1987;78:151–164. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(87)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Acqua ML, Smith KE, Gorski JA, Horne EA, Gibson ES, Gomez LL. Regulation of neuronal PKA signaling through AKAP targeting dynamics. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineley KT, Hogan D, Zhang WR, Taglialatela G. Acute inhibition of calcineurin restores associative learning and memory in Tg2576 APP transgenic mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;88:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulga TA, Elson-Schwab I, Khurana V, Steinhilb ML, Spires TL, Hyman BT, Feany MB. Abnormal bundling and accumulation of F-actin mediates tau-induced neuronal degeneration in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:139–148. doi: 10.1038/ncb1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KN. Calcium in the initiation, progression and as an effector of Alzheimer's disease pathology. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2787–2799. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1986;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureviciene I, Ikonen S, Gurevicius K, Sarkaki A, van Groen T, Pussinen R, Ylinen A, Tanila H. Normal induction but accelerated decay of LTP in APP + PS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiology of Disease. 2004;15:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K, Lee A, Song L, Kanold PO, Lee HK. AMPA receptor subunit GluA1 (GluA1) serine-845 site is involved in synaptic depression but not in spine shrinkage associated with chemical long-term depression. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2011;105:1897–1907. doi: 10.1152/jn.00913.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler RW, Grimm KM, Nahas DD, Breese R, Dodson EC, Acton P, Keller PM, Yeager M, Wang H, Shughrue P, Kinney G, Joyce JG. Solution state characterization of amyloid beta-derived diffusible ligands. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15157–15167. doi: 10.1021/bi061850f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper C, Killick R, Lovestone S. The GSK3 hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2008;104:1433–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover BR, Reed MN, Su J, Penrod RD, Kotilinek LA, Grant MK, Pitstick R, Carlson GA, Lanier LM, Yuan LL, Ashe KH, Liao D. Tau Mislocalization to Dendritic Spines Mediates Synaptic Dysfunction Independently of Neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2010;68:1067–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Boehm J, Sato C, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron. 2006;52:831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulette CM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Murray MG, Saunders AM, Mash DC, Mcintyre LM. Neuropathological and Neuropsychological Changes in “Normal” Aging: Evidence for Preclinical Alzheimer Disease in Cognitively Normal Individuals. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:1168. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, Wölfing H, Chieng BC, Christie MJ, Napier IA, Eckert A, Staufenbiel M, Hardeman E, Götz J. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam AYF, Liao D, Loh HH, Law PY. Morphine Induces AMPA Receptor Internalization in Primary Hippocampal Neurons via Calcineurin-Dependent Dephosphorylation of GluA1 Subunits. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:15304–15316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4255-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003;37:925–937. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla KV, Goldman ST, Lattarulo CR, Wu HY, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Abeta plaques lead to aberrant regulation of calcium homeostasis in vivo resulting in structural and functional disruption of neuronal networks. Neuron. 2008;59:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Viola KL, Chromy BA, Chang L, Morgan TE, Yu J, Venton DL, Krafft GA, Finch CE, Klein WL. Vaccination with soluble Abeta oligomers generates toxicity-neutralizing antibodies. J Neurochem. 2001;79:595–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz TA, Carter DB, Merchant KM. Dendritic spine loss in the hippocampus of young PDAPP and Tg2576 mice and its prevention by the ApoE2 genotype. Neurobiology of Disease. 2003;13:246–253. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurén J. Cellular prion protein as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38:227–244. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Kameyama K, Huganir RL, Bear MF. NMDA induces long-term synaptic depression and dephosphorylation of the GluA1 subunit of AMPA receptors in hippocampus. Neuron. 1998;21:1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJR, Escobedo-Lozoya Y, Szatmari EM, Yasuda R. Activation of CaMKII in single dendritic spines during long-term potentiation. Nature. 2009;458:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nature07842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesné S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Lin H, Law PY, Loh HH. Mu-opioid receptors modulate the stability of dendritic spines. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2005;102:1725–1730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406797102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Scannevin RH, Huganir R. Activation of silent synapses by rapid activity-dependent synaptic recruitment of AMPA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:6008–6017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Zhang X, O’Brien R, Ehlers MD, Huganir RL. Regulation of morphological postsynaptic silent synapses in developing hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:37–43. doi: 10.1038/4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman DN, Mody I. Regulation of NMDA channel function by endogenous Ca(2+)-dependent phosphatase. Nature. 1994;369:235–239. doi: 10.1038/369235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Drewes G, Gustke N, Trinczek B, Mandelkow E. Tau domains, phosphorylation, and interactions with microtubules. Neurobio of Aging. 1995;16:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00025-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Terry RD, DeTeresa RM, Hansen LA. Immunohistochemical quantification of the synapse-related protein synaptophysin in Alzheimer disease. Neurosci Lett. 1989;103:234–239. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90582-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EC, Zhang L, Dummer BW, Cariveau DR, Loh HH, Law PY, Liao D. Differential Modulation of Drug-Induced Structural and Functional Plasticity of Dendritic Spines. Molecular Pharmacology. 2012;82:333–343. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu GQ, Mallory M, Rockenstein EM, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Johnson-Wood K, McConlogue L. High-level neuronal expression of abeta 1–42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey RM, Endo S, Shenolikar S, Malenka RC. Involvement of a calcineurin/inhibitor-1 phosphatase cascade in hippocampal long-term depression. Nature. 1994;369:486–488. doi: 10.1038/369486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey RM, Herron CE, Malenka RC. An essential role for protein phosphatases in hippocampal long-term depression. Science. 1993;261:1051–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.8394601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullan M, Crawford F, Axelman K, Houlden H, Lilius L, Winblad B, Lannfelt L. A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer’s disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of beta-amyloid. Nat Genet. 1992;1:345–347. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Vasilevko V, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM. Reduction of soluble Abeta and tau, but not soluble Abeta alone, ameliorates cognitive decline in transgenic mice with plaques and tangles. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39413–39423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson M, Yasuda R. Signalling pathways underlying structural plasticity of dendritic spines. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;163:1626–1638. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C. Alzheimer’s disease and the amyloid cascade hypothesis: a critical review. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:369808. doi: 10.1155/2012/369808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Halabisky B, Yoo JW, Yao J, Chin J, Yan F, Wu T, Hamto P, Devidze N, Yu GQ, Palop JJ, Noebels JL, Mucke L. Amyloid- /Fyn-Induced Synaptic, Network, and Cognitive Impairments Depend on Tau Levels in Multiple Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:700–711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4152-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ, Mucke L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, Paulson J, Kotilinek L, Ingelsson M, Guimaraes A, DeTure M, Ramsden M, McGowan E, Forster C, Yue M, Orne J, Janus C, Mariash A, Kuskowski M, Hyman B, Hutton M, Ashe KH. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309:476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, Townsend M, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Sabatini BL. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Sabatini BL, Sudhof TC. Synapses and Alzheimer’s Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2012;4:a005777–a005777. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha BR, Vitolo OV, Joshi P, Lordkipanidze T, Shelanski M, Dunaevsky A. Amyloid beta peptide adversely affects spine number and motility in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;33:274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Acton PJ, Breese RS, Zhao WQ, Chen-Dodson E, Hepler RW, Wolfe AL, Matthews M, Heidecker GJ, Joyce JG, Villarreal SA, Kinney GG. Anti-ADDL antibodies differentially block oligomer binding to hippocampal neurons. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31:189–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, Greengard P. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilb ML, Dias-Santagata D, Mulkearns EE, Shulman JM, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Feany MB. S/P and T/P phosphorylation is critical for tau neurotoxicity in Drosophila. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1271–1278. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine WB, Dahlgren KN, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-beta peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11612–11622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydow A, Van der Jeugd A, Zheng F, Ahmed T, Balschun D, Petrova O, Drexler D, Zhou L, Rune G, Mandelkow E, D’Hooge R, Alzheimer C, Mandelkow EM. Tau-Induced Defects in Synaptic Plasticity, Learning, and Memory Are Reversible in Transgenic Mice after Switching Off the Toxic Tau Mutant. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:2511–2525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5245-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A, Noguchi K, Michel G, Mercken M, Hoshi M, Ishiguro K, Imahori K. Exposure of rat hippocampal neurons to amyloid beta peptide (25–35) induces the inactivation of phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase and the activation of tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta. Neurosci Lett. 1996;203:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, Hansen LA, Katzman R. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JZ, Xia YY, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau: sites, regulation, and molecular mechanism of neurofibrillary degeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S123–S139. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JZ, Wu Q, Smith A, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Tau is phosphorylated by GSK-3 at several sites found in Alzheimer disease and its biological activity markedly inhibited only after it is prephosphorylated by A-kinase. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:28–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens KM, Lin H, Liao D. Rac1 induces the clustering of AMPA receptors during spinogenesis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:10627–10636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1947-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Hudry E, Hashimoto T, Kuchibhotla K, Rozkalne A, Fan Z, Spires-Jones T, Xie H, Arbel-Ornath M, Grosskreutz CL, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT. Amyloid beta induces the morphological neurodegenerative triad of spine loss, dendritic simplification, and neuritic dystrophies through calcineurin activation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:2636–2649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4456-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahs KR, Ashe KH. β-Amyloid oligomers in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:28. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H, Luedtke J, Kumar Y, Biernat J, Dawson H, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Amyloid-β oligomers induce synaptic damage via Tau-dependent microtubule severing by TTLL6 and spastin. EMBOJ. 2013;32:2920–2937. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. A Oligomers Cause Localized Ca2+ Elevation, Missorting of Endogenous Tau into Dendrites, Tau Phosphorylation, and Destruction of Microtubules and Spines. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:11938–11950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Homma KJ, Poo MM. Shrinkage of Dendritic Spines Associated with Long-Term Depression of Hippocampal Synapses. Neuron. 2004;44:749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]