Abstract

Drawing on the mobilization-minimization hypothesis, this research examines the influence of positive job experiences and generalized workplace harassment (GWH) on employee job stress and well-being over time, postulating declines in the adverse influence of GWH between Time 1 and 2, and less pronounced declines in the influence of positive job experiences over this same timeframe of approximately one year. A national sample of 1,167 workers polled via telephone at two time periods illustrates that negative job experiences weigh more heavily on mental health than do positive job experiences in the short-term. In the long-term, GWH’s association with mental health and job stress was diminished. But its effects on job stress, and mental health, and physical health persist over one year, and, in the case of long-term mental health, GWH overshadows the positive mental health effects of positive job experiences. The research also argues for a reconceptualization of GWH and positive job experiences as formative latent variables on theoretical ground.

Keywords: Aggression, Anti-social behavior, Generalized workplace harassment, Stress, Burnout, Well-being

On the one hand, recent years have seen an upswing in media and scholarly attention to “the bad” in organizations--workplace aggression and deviance (Bennett & Robinson, 2003), and the coining of constructs such as organizationally motivated aggression (O’Leary-Kelly, Griffin & Glew, 1996), anticitizenship (Youngblood, Terviño, & Favia, 1992), tyranny (Ashforth, 1994), abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000), and negative mentoring (Eby, Butts, Lockwood, & Simon, 2004). On the other, positive organizational scholarship has risen to unprecedented levels by providing “a frame…for current and future research on positive states [and] outcomes…” (Roberts, 2006). With the latter the emphasis is on “the good”--strengths and virtues that foster the best of human qualities, such as generativity, growth, and resilience (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005). But in his critique of the positive movement, Fineman (2006, p. 275) argues that “focusing exclusively on the positive…represents a one-eyed view of the social world,” reflecting the stark reality of human experience – positive experiences, learning, and change are most enduring when encountered alongside negative emotions, stressful events, and disappointments.

Responding to the coexistence of positive and negative factors in organizational contexts and the experiences of most members, this study seeks to understand the concurrent influence that negative and positive forces can engender in individuals over time. Although some ethnographic research has looked at concurrent positive and negative influencers (e.g., Dutton & Dukerich, 1991; Pratt & Rosa, 2003), the joint effects of positive and negative factors on individuals have been for the most part ignored, despite the idea that assessing a wider spectrum of everyday events provides a “more complete representation of the person” (Zautra, Affleck, Tennen, Reich, & Davis, 2005, p. 1514). Understanding the joint effects of positive and negative factors will allow researchers to paint a more realistic picture of workplace experiences and provide guidance to practitioners on how to better manage and understand the ramifications of workers’ daily experiences.

Using a national sample of 1,167 workers, we assess the effects of positive and negative job experiences on desirable and undesirable outcomes often associated with such experiences. With two waves of data roughly one year apart, we examine the concurrent effects of “good” and “bad” organization experiences on job stress and mental and physical health over time. We look at the longitudinal impact of generalized workplace harassment (GWH; harassment experiences at work inclusive of verbal aggression, disrespect, isolation/exclusion, threats/bribes, and physical aggression; Rospenda & Richman, 2004) and positive job experiences (e.g., being valued by the organization, being praised for a job well done; Keashly, Trott, & MacLean, 1994) on 1) job stress, 2) mental health, and 3) physical health. Moreover, we apply the mobilization-minimization hypothesis (Taylor, 1991) to predict a pattern of asymmetrically diminishing effects of these experiences over two time periods. In addition, we argue for operationalizing GWH and positive job experiences as formative latent constructs instead of using the reflexive operationalization implicit in past research (e.g., Rospenda & Richman, 2004). Treating GWH and positive job experiences as formative constructs is more in line with true score theory (Lord & Novick, 1968) than past treatments of these constructs, and responsive to admonitions for a more careful alignment of theoretical and operational models in psychological research (e.g., Jarvis, Mackenzie, & Podsakoff, 2003).

Theory and Hypotheses

In the 1960s Bradburn developed a scale of emotional well-being (1969), and controversially concluded that positive and negative affect (general dimensions of subjective mood represented broadly by pleasantness and unpleasantness) were not opposites, but two separate components of happiness. This supported humanist researchers, (e.g., Maslow, 1943), in their assertion that enhancing life is premised both on reducing negative affect and increasing positive affect (Diener, 1984). Similarly, in the 1990s, Taylor (1991) argued that physiological, affective, cognitive, and behavioral reactions to negative and positive events are different at different points of occurrence.

Evidence exists that psychology has spent more time focused on negative events and their consequences than positive events (Cacioppo, Bernston, & Gardner, 1999). One reason for this is the quest to understand adaptive responses to threat (Zautra et al., 2005). Yet recent indications point to people experiencing five to six times as many positive events as negative events in daily life (Zautra et al., 2005). Moreover, studies of the positive provide added information about persons and their lives that negative assessments cannot achieve alone. For example, early studies of happiness (Bradburn, 1969) showed that items measuring positive aspects of daily life were not inversely correlated with negative aspects. The absence of positive daily events does not indicate the presence of negative daily events; the relationship is more complex. That is, both are important. The co-existent nature of positive and negative feelings is further articulated by Fineman’s (2006) proposal that negative events can engender learning, adaptation and ultimately change. Focusing exclusively on one type of event leaves out the “frustrations…and contradictions” (Fineman, 2006; p. 275) inherent in personal and social development and satisfaction, such as when love is sharpened by jealously, pride marred by hubris, and stressful events inform and mold moral character.

Taylor’s mobilization-minimization hypothesis (Taylor, 1991) offers a way of understanding the valence of negative and positive events and assists in predicting short- and long-term responses to both. The mobilization-minimization hypothesis predicts that for adverse or threatening (negative) events, humans respond with strong physiological, cognitive, emotional, and social responses. The body is aroused by the endocrine and sympathetic nervous systems whereby the heart races, blood pressure increases, and respiration quickens. Physiological stress is evoked such that humans are thrown into a state of readiness for flight or attack. In explaining this state of arousal, people often report feeling uneasy, nervous, or anxious (Marshall & Zimbardo, 1979). As Taylor (1991) notes, an abundance of laboratory-based stress research finds this type of psychological arousal more closely linked to negative events than positive ones, although it has been shown that positive events may also induce negative arousal, such as when self-doubt and even depression follow the birth of a child. As it pertains to attributions, research shows that negative aspects of an object, event, or choice elicit more causal attributions than do positive events (Peeters & Czapinksi, 1990). In contrast, an upbeat mood stemming from positive events has been linked to automatic, effortless information-processing strategies (Taylor, 1991).

Following the mobilization or arousal stage is minimization, or abatement of the arousal. After the nervous system is aroused in response to adverse or negative events, humans and animals engage in a compensatory process (Taylor, 1991) whereby the parasympathetic nervous system “steps down” arousal and moves the organism toward normalcy (Levinthal, 1990). While extreme positive emotions like exhilaration may be followed by periods of neutral mood or emotion, no evidence exists that they are followed by negative emotions such as anger or depression. In contrast, negative events such as those that evoke fear are often later accompanied by relief or safety reactions. Moreover, in the long-term, negative events, despite resulting in higher levels of cognitive activity, are less accessible in memory and are hence less likely to influence individuals’ future attitudes and behaviors. People are more likely to remember positive rather than negative events of a comparable magnitude (e.g., White, 1982). Humans attempt to reclassify negative information, and they process positive information more efficiently and accurately (Taylor & Brown, 1988). The general conclusion from such research is that negative events weigh more heavily than the positive ones in the short term, but after encoding, declines in the influence of both types of events tend to take place.

Positive and Negative Influences in Organizational Contexts

We expect that individuals will be aroused by negative events, both because of the human responses to negative events already discussed, and the enhancing influence to such responses that social contexts can engender. Organizational life invites social comparisons, wherein individuals utilize social cues to understand what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable behaviors (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). Consequently, even more pronounced responses can be expected when negative experiences arise in contexts where specific social responses are required or expected, because of added concern over the appropriateness of one’s response to the event against the organization’s social norms and cues. As for positive events, initial arousal should be lower in the short-term, with less of a minimizing or dampening effect over time. Based on the mobilization-minimization hypothesis, the strength of the effects of positive events is expected to dissipate over time, but not as severely as negative events.

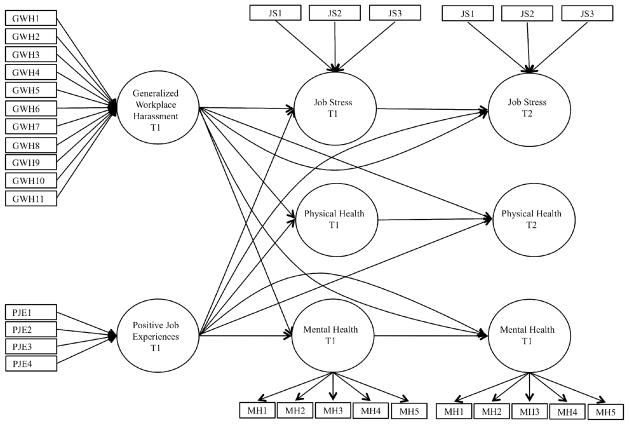

Within organizational contexts, we focus on two documented antecedents to negative and positive outcomes: generalized workplace harassment and positive job experiences. Generalized workplace harassment (GWH) is conceptualized as an overall employee sense of mistreatment at work, derived from the integration of negative experiences into an experiential singularity and operationalized as such (Rospenda & Richman, 2004; Rospenda, Richman, Ehmke, & Zlatoper 2005). Generalized harassment has been studied under various labels (e.g., incivility, bullying, emotional abuse, mobbing, workplace aggression, relational victimization) emphasizing different aspects of the behaviors in question (i.e., duration, motivation, target-perpetrator power differences; see Keashly & Jagatic, 2003 for a review of these issues). For example, the related term “incivility” emphasizes minor forms of disrespectful workplace behavior, where intent to harm the target of such behaviors is ambiguous (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Because duration, power, and labeling are not central to the broader conceptualization of this type of behavior, and all definitions of harassment and related behaviors include the core features of negative interpersonal mistreatment that ultimately cause harm to the target (Rospenda & Richman, 2005; Saunders, Huynh & Goodman-Delahunty, 2007), we use the term “generalized harassment” to describe negative behaviors that encompass verbal aggression, disrespectful or exclusionary behavior, isolation/exclusion, threats or bribes, and physical aggression, that are not obviously related to legally protected characteristics (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, age, disability), and which do not explicitly reference duration of experiences, perpetrator motivation, or target-perpetrator power differentials. Positive job experiences are likewise construed as a generalized assessment stemming from the integration of diverse affirming events (e.g., Keashly, Trott, & MacLean, 1994). The hypothesized influence of GWH and positive job experiences on job stress, mental health, and physical health are illustrated in Figure 1 and discussed below.

Figure 1.

Model of generalized workplace harassment and positive job experiences’ effects on job stress and physical and mental health over time. a

a GWH = Generalized Workplace Harassment

PJE = Positive Job Experiences

JS = Job Stress

MH = Mental Health

Job Stress

Psychological stress refers to a particular type of relationship between person and environment (Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), such as when work and social demands strain or exceed a person’s resources. The extent to which a certain event or series of events are “stressful” is determined by an individual’s appraisal of his or her experience, that is, their meaningfulness (Lazarus, 1991). As such, job stress has been a focus of research efforts for several decades (Hurrell, Nelson, & Simmons, 1998). Factors such as role ambiguity, workload, role conflict, and relations with one’s work group and supervisor have been found to contribute to perceptions of job stress (e.g., French & Kahn, 1962; Hackman & Oldham, 1975), and factors such as depression, anxiety, and job dissatisfaction have been shown to be consequences of stress (c.f., Hurrell & Murphy, 1992).

A large body of evidence illustrates the relationship between a variety of negative workplace experiences and job stress (e.g., Fitzgerald, Drasgow, Hulin, Gelfard, & Magley, 1997; Greiner, Krause, Ragland, & Risher, 1998; Gates, Fitzwater, & Succop, 2003). Related to this study, Rospenda and colleagues (2005) supported the idea that GWH is associated with worker job stress. Our model makes the same prediction, but calls on the mobilization-minimization hypothesis to predict a declining influence of GWH over time. More specifically, we expect that:

-

H1

Generalized workplace harassment relates positively to job stress in the short term, with a weaker positive relationship in the long term.

The research generally does not support a negative relationship between positive job experiences and stress. A handful of studies have suggested that positive events may act as stress buffers by providing “breathers” which restore depleted psychological resources (Lazarus, Kanner, & Folkman, 1980), but depression is the only outcome for which positive events have been found to “buffer” negative effects (Jackson, 1992; Harris & Kacmar, 2005) to date. In line with previous research (Cohen, McGowan, Fooskas, & Rose, 1984), we do not predict a direct relationship between positive job experiences and reported job stress.

Well-being

Congruent with Bradburn (1969), positive and negative work experiences operate independently on well-being (Headey & Wearing, 1992). Positive workplace experiences may actually enhance well-being (c.f., Deci & Ryan, 2000; Hart, Wearing, & Headey, 1993; Heuven, Bakker, Schaufeli, & Huisman, 2006), while a host of negative workplace experiences, such as social undermining by supervisors and coworkers (c.f., Kohan & Mazmanian, 2003; Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, 2002) can diminish well-being.

Mental Health

Mental health is a common indicator of well-being, but research on the effects of positive experiences on mental health is relatively sparse (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Fredrickson’s (2001) broaden-and-build theory argues that positive events and the emotions they engender broaden one’s cognitions and actions and foster growth and coping skills, and as a result, durable physical, cognitive, and social resources like intellectual exploration, and sharing with others (e.g., Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002; Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003) manifest. Moreover, these resources can promote multiple flourishing outcomes for social relationships, work, and physical and mental health (c.f., Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). Hence, we expect positive job experiences to enhance mental health, tempered by the effects of mobilization and minimization mechanisms.

In contrast, experiencing negative events such as derogatory and hostile interactions with people can undermine mental health (Keashly et al., 1994). Negative events engender fear and reduced self-esteem (Brockner, 1988). Strong links between workplace bullying, abusive supervision, incivility (constructs related to GWH in that they entail workplace status derogation and displays of hostility), and poor mental health such as depressive symptoms have been found (Cortina, Magley, Williams, & Langhout, 2001; Lim & Cortina, 2005; Lim, Cortina, & Magley, 2008; Niedhammer, David, & Degioanni, 2006; Tepper, 2000). Such emotional abuse has also been found to have short- and long-term effects on victims’ self-perceptions and overall mental health (Keashly & Harvey, 2005). Finally, Bowling and Beehr’s (2006) meta-analysis showed consistent, strong effects of workplace harassment on many indicators of well-being including strain, depression, burnout, frustration, self-esteem, and job and life satisfaction, over many studies. Combining the concurrent influences of positive job experiences and GWH with the effects over time predicted by the mobilization-minimization hypothesis, we thus expect that:

-

H2

Positive job experiences relate positively to mental health in the short term, with a weaker positive relationship in the long term.

-

H3

Generalized workplace harassment relates negatively to mental health in the short term, with a weaker negative relationship in the long term.

-

H4

In the short term, the relationship between generalized workplace harassment and mental health is stronger than the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health.

-

H5

In the long term, the relationship between generalized workplace harassment and mental health is weaker than the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health.

Physical Health

Physical health also contributes to well-being. Positive experiences have been shown to promote physiological adaptation, ultimately resulting in better health outcomes (Zautra et al., 2005). Individuals who experience greater positive emotions exhibit faster blood pressure recovery in response to stress, which is an important cardiovascular health indicator (Tugade, Fredrickson, & Feldman-Barrett, 2004). Likewise Cohen, Doyle, Turner, Alper, and Skoner (2003) found that susceptibility to a cold virus was greater among individuals reporting fewer positive emotions, while susceptibility was unrelated to levels of negative emotions. Moreover, Brown and McGill (1989) have shown that for certain personality types, positive life events are linked to physical well-being. In the workplace, characteristics that have been shown to enhance well-being include social support from fellow employees, perceived control (Halbesleben, Osburn, & Mumford, 2006), and autonomy (Hall et al., 2006).

Negative events are more salient to individuals and often generate intense emotional and physiological reactions (Duffy et al., 2002). Range-frequency theory (Kanouse & Hanson, 1972) echoes this idea, arguing that because of negative events’ unexpectedness, they require more consideration and consume greater cognitive resources. Negative encounters and interactions, such as those typified by GWH, generate self-blame, self-doubt, and at times isolation on the part of the target (Rook, 1992), and these emotions can present themselves as somatic health symptoms, such as headaches, dizziness, and tightness in the chest (Duffy et al., 2002). More specific to our model, being the target of workplace verbal abuse has been linked to physical illness (Bowling & Beehr, 2006; Cox, 1991). Bowling and Beehr’s (2006) meta-analysis documented a strong, positive association between workplace harassment and physical symptomology (mean = .31). We thus combine the influence of positive and negative events on physical health outcomes with the predictions of the mobilization-minimization hypothesis to propose that:

-

H6

Positive job experiences relate positively to physical health in the short term, with a weaker positive relationship in the long term.

-

H7

Generalized workplace harassment relates negatively to physical health in the short term, with a weaker negative relationship in the long term.

-

H8

In the short term, the relationship between generalized workplace harassment and physical health is stronger than the relationship between positive job experiences and physical health.

-

H9

In the long term, the relationship between generalized workplace harassment and physical health is weaker than the relationship between positive job experiences and physical health.

Method

Sample

Random digit dial telephone survey methodology was used to contact households within the continental United States at time 1 (August 2003 through February 2004).1 Brief advance letters with information about the study were sent to all cases with a listed address. Using trained telephone interviewers, households were screened for number of adults (age 18+) who had worked at least 20 hours/week at some point in the past 12 months. Where multiple adults met these criteria, one adult was selected for participation using the Troldahl-Carter-Bryant method (Lavrakas, 1986). Out of 4,116 households with eligible individuals, n=2,151 (52.3%; 1,067 women and 1,083 men, with 1 missing data on gender) agreed to participate. At time 2 (August 2004 through December 2004), time 1 respondents who agreed to receive future calls (n=1,962) were contacted a second time. A total of 1,418 completed the time 2 interview (66% retention rate), and the overall response rate was 34.5%. Interviews averaged 30 minutes and were conducted in English or Spanish (3%). Respondents were sent a $10 incentive at time 1 and $20 at time 2. In terms of demographic differences between those who did and did not complete a survey at time 2, non-completers were more likely to be Black and Hispanic, to be younger, and have lower mean income and educational levels (p <.01). Completers had higher levels of positive job experiences, and higher levels of overall mental health (p < .05).

Because we are interested in how positive and negative events in a certain job affect workers’ outcomes, only data from the 1,167 respondents who remained in the same job at time 2 were used in this study. The 1,167 respondents included 582 women and 585 men whose average age at time 2 was 47.15 (SD=11.94) and average tenure in their job at time 2 was 10.61 years (SD=9.58). The sample was 79.1% white, 7.5% black, 4.7% Latino, and 7.8% Asian or other. Respondents were primarily employed in professional (31.9%), sales/office (21.6%), management/business (15.9%), service (10.2%), construction/extraction (9.0%), and production/transportation (9.9%) occupations. (Totals do not sum to 100% due to missing data.) GWH and positive job experiences were measured at Time 1 while outcomes were measured at Time 1 and Time 2.

Measures

Generalized Workplace Harassment

GWH was measured by a shortened version of the Generalized Workplace Harassment Questionnaire (GWHQ; Rospenda & Richman, 2004), which was developed to address five conceptual dimensions: verbal aggression (e.g., “made negative comments about your intelligence”), disrespectful behavior (e.g., “humiliated you in front of others”), isolation/exclusion (e.g., “ignored you”), threats/bribes, and physical aggression (e.g., “hit, pushed, or threw things at you”). Eleven items were included in the present study. Items were selected for inclusion based on item-total correlations and overall representation of the original conceptual subscales using existing data from a university sample (see Richman, Fendrich, Wislar, Flaherty, & Rospenda, 2004 and Rospenda & Richman, 2004 for descriptions of the data used), to ensure that the shortened version represented all the concepts relevant in the original measure. Items were rated for occurrence in the past 12 months and measured on a 3-point scale 1= “Never,” 2= “Once,” and 3=“More than once.”

Positive Workplace Experiences

Four items drawn from Keashly et al. (1994) were used to measure positive workplace experiences (e.g., “told I was valuable to the organization,” “praised for doing a good job”). Keashly and scholars developed these items to be counterparts to items assessing negative workplace experiences, and to provide for a more complete picture of workers’ experiences on the job. The four items chosen for inclusion in the present study were selected based on their high mean ratings of positive impact, and because they represent behaviors initiated by a variety of fellow workers (i.e., coworkers and subordinates, in addition to supervisors). Items were rated for occurrence in the past 12 months on the same three-point scale as the generalized workplace harassment items.

Job Stress

A modified 7-item version of the Stress in General Scale (SIG; Stanton, Balzer, Smith, Parra, & Ironson, 2001) was used to measure general job stress at Times 1 and 2 (Time 1 α =.74; Time 2 α =.73). The SIG was developed to broadly measure the general experience of workplace stress, rather than frequencies or amounts of certain job stressors. We used the three-item Pressure subscale where respondents are asked to indicate whether each of a series of descriptors fits their job. Items are rated on a 3-point scale: “yes,” “no,” and “can’t decide.” “Yes” responses, indicating a higher level of stress, were coded as 3, “can’t decide” responses were coded as 1.5, and responses indicating low stress were coded as 0, as per Stanton et al. (2001). The SIG has demonstrated good convergent validity with appropriate correlations with various job stressors and systolic blood pressure, and has been shown to be distinct from the construct of job satisfaction (Stanton et al., 2001).

Mental Health was measured at Times 1 and 2 with the five-item version of the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5; Davies, Sherbourne, & Peterson, 1988) (Times 1 and 2 α=.77). The MHI-5 is a general indicator of overall distress and mental well-being for use in general populations. Items are scored on a six-point scale (1=“All of the time” to 6=“None of the time”). The MHI-5 is a brief form of the Mental Health Inventory (Veit & Ware, 1983), and includes items for anxiety, depression, loss of behavioral/emotional control, and psychological well-being. The MHI-5 has been found to correlate (r=.95) with the original 38-item version of the MHI (Davies et al., 1988). Convergent validity of the MHI-5 has been demonstrated through its correlation with other measures of mental health, such as depression, and its lack of relationship to other measures such as physical functioning (McHorney & Ware, 1995).

General Physical Health was measured at Times 1 and 2 by a single item as described by Bird and Fremont (1991): “Compared to other people your age, would you say that your health is (1) poor, (2) fair, (3) good, or (4) excellent?” Although research indicates that stress can increase susceptibility to disease, it does not necessarily result in specific patterns of disease (e.g., Selye, 1985). Self-rated, one-item indicators of health are widely used in large population studies such as the National Health Interview Survey (Lethbridge-Cejku, Schiller, & Bernadel, 2004) and have been found to significantly predict mortality, controlling for functional health status, cognitive status, depression, and comorbid illness (DeSalvo, Bloser, Reynolds, He, & Muntner, 2005). The measure used here has been found to be correlated with “objective” measures of health, such as physicians’ assessments (e.g., Okun & George, 1984).

Evidence for Affective Equivalency of Exogenous Variables

The authors acknowledge that all positive events and negative events are not created equal. As such, we wished to structure a model of “the good and the bad” which approximated affective equivalency, and hence in choosing the exogenous variables for the model sought positive and negative experiences that had similar valence to respondents (c.f. Gable, Reis, & Elliot, 2000). Previous research using measures longer but similar to GWH and positive job experiences has shown that those who experience these types of events rate their impact as similar but in opposite directions. The GWH items that we employed in this research were based in part on the abusive interpersonal workplace events in Keashly and colleagues’ (1994) research (personal conversation between L. Keashly and K. Rospenda, 2006) and the positive job experiences items were taken directly from this same manuscript. In that Keashly and colleagues (1994) established the approximate equivalent impact of these positive and negative interpersonal work events, we apply their findings to the research here. Specifically, in the Keashly study, while the number of negative events one experienced weighed more heavily on job satisfaction than did the positive, the impact of positive events on job satisfaction (r = .45, p<.01) was quite similar to the impact of negative events on job satisfaction (r = −.48, p<.01).

Analytic Strategy

We relied on 1) structural equation modeling (SEM) for a simultaneous test of our hypotheses and 2) significance testing to assess path estimate magnitude differences between the two time periods (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). SEM allows us to test the simultaneous influence of positive and negative events on outcomes while allowing for the continuity of outcomes across time periods and as such provides a more realistic assessment of the observed relationships. To test for changes in the path estimates between Time 1 and Time 2 (H1, H2, H3, H6, and H7), we used two-group analysis (Byrne 1994), designating the influence of GWH and positive job experiences on job stress, mental health, and physical health at Time 1 as Group 1, and the influence of the same antecedents at Time 1 on outcomes at Time 2 as Group 2. The analysis allows us to constrain the path estimates between the antecedents and outcomes (e.g., GWH to job stress) to be equal for Time 1 and Time 2 as a test of the null hypothesis (e.g., no difference between time effects) and to remove the constraints to test the listed hypotheses. The change in the chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic over the appropriate change in degrees of freedom when path constraints are removed provides an overall indication of model fit improvement (e.g., Bagozzi & Yi, 1993; Byrne, 2004). The statistical significance of differences in the path estimates between Time 1 and Time 2 for H1, H2, H3, H6 and H7, and for the differential influences of the various antecedents on outcomes (H4, H5, H8, and H9) was determined through dependent beta z-tests (Cohen & Cohen, 1983) for the corresponding path estimates. The two-group analysis estimation alters the standardized values being compared across the time periods without distorting the underlying measured influences and as such provides a more definitive representation of how the focal outcomes at Time 1 and Time 2 are influenced by GWH and positive job experiences measures at Time 1.

Structural equation modeling also allows for operational definitions of GWH and positive job experiences that are better aligned with their theoretical foundations than what has been used in prior research (e.g., Rospenda & Richman, 2004). Both GWH and positive job experiences are conceptualized as aggregations of events that produce a holistic sense of harassment or positive experience, not unlike how factors such as education, income, and race come together to shape self-assessed social class, or how aesthetic characteristics, product performance, and price come together to determine consumer perceptions of value. Previous research has relied on composite scores to represent GWH and positive job experiences, which implicitly treat the individual items as reflective of a latent and not-directly-measurable construct (Lord & Novick 1968). Using SEM, we model GWH and positive job experiences as formative constructs (e.g., Bagozzi, 1994) to acknowledge that not all events comprising GWH and positive workplace experiences have to happen to a person for him or her to feel negatively or positively about workplace events. As Jarvis and colleagues (2003) summarize, a formative variable model is aptly employed when there is no reason to expect correlation among all items and a scale score does not adequately represent the construct. Job stress and mental health, in contrast, were modeled as reflective constructs, and physical health was modeled as a single item construct.

The method of estimation used was maximum likelihood (ML) and the software utilized was AMOS 7.0 (Arbuckle, 2006). As far as measures of goodness-of-fit, the widely-used χ2 statistic was used, yet because it is not interpretable as a standardized value and is sensitive to sample size, other fit indices (see Results) were employed as well (Hu and Bentler, 1999). As recommended for formative indicators, the measurement error terms for the eleven GWH items and the four positive job experiences items were allowed to covary (Jarvis et al., 2003). The error terms for the latent, endogenous variables were allowed to covary at Time 2 to reflect noise which may have accrued distally from when the exogenous variables were measured (e.g., changes in work conditions). Finally, in fitting the measurement model, within both time periods error variances for two mental health items phrased in the affirmative (felt cheerful and lighthearted, generally enjoyed the things you do) were unconstrained, and error terms for similarly worded mental health and job stress items were allowed to covary.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and variable correlations. The relationships and signs on the correlations are consistent with previous research. For example, generalized workplace harassment was negatively related to mental health at both time periods. A point on Table 1 that bears mentioning is that, despite lack of predictive evidence regarding an association between positive job experiences and job stress (see Theory and Hypotheses above), we found a significant, consistent relationship across two time periods. Insert Table 1 about here.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 Variables | |||||||||

| 1. GWH a | 15.86 | 4.43 | |||||||

| 2. Positive Job Experiences | 11.05 | 1.53 | −.19*** | ||||||

| 3. Job Stress | 6.33 | 3.11 | .39*** | −.12*** | |||||

| 4. Mental Health | 15.85 | 2.42 | −.30*** | .15*** | −.37*** | ||||

| 5. Physical Health | 3.53 | 1.01 | −.10*** | .08** | −.13*** | .27*** | |||

| Time 2 Variables | |||||||||

| 6. Job Stress | 6.27 | 3.12 | .28*** | −.12*** | .64*** | −.31*** | −.15*** | ||

| 7. Mental Health | 16.04 | 2.29 | −.21*** | .10*** | −.30*** | .57*** | .26*** | −.33*** | |

| 8. Physical Health | 3.54 | .99 | −.09** | .10*** | −.15*** | .24*** | .65*** | −.17*** | .27*** |

N = 1,167.

Generalized Workplace Harassment

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Structural Equation Modeling

Overall, the model presented in Figure 1 fit the data well: χ2(421, N = 1,167) = 1526.9, non-normed fit index (NNFI) = .92, comparative fit index (CFI) = .93, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .04. Because we formulate the two predictive constructs as formative, an examination of the respective factor loadings in Table 2 is in order, and we find that it reveals some non-significant loadings. For our sample, only 5 of the 11 components of GWH contributed to the GWH underlying construct. Specifically, being the recipient of hostile and offensive gestures, public humiliation and embarrassment, having work contributions ignored, being excluded from important work activities, and physical violence factored significantly in respondent perceptions of GWH (b =.09, .21, .20, .08, and .17 respectively). Similarly, only two of the four positive job experiences indicators were significant shapers of positive job experiences for our sample. Being told how valuable you are to the organization (b =.15) and having been in a situation where someone treated you as an equal at work (b = .08), both in the past 12 months, were significant indicators. A lack of significant influence from previously postulated components of GWH and positive job experiences in our study, however, does not call into question the veracity of theoretical arguments for such factors shaping GWH and positive job experiences in other contexts. Our results merely suggest that for our sample it was a subset of the factors that contributed significantly to the GWH and positive job experience mechanisms, and the theory behind these constructs rightly agrees.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Indicators

| Indicator | Mean | S. D. | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formative Indicators | |||

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 1: hostile/offensive gestures | 1.43 | 0.75 | .54** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 2: labeled troublemaker for opinion | 1.37 | 0.71 | .08 |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 3: humiliated/embarrassed | 1.35 | 0.66 | .56** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 4: ignored you or your work contribution | 1.58 | 0.84 | .56** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 5: turned others against you | 1.27 | 0.62 | .03 |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 6: negative comments about you/your IQ | 1.37 | 0.71 | .06 |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 7: left notes/signs to hurt/embarrass | 1.09 | 0.38 | .06 |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 8: treated unfairly | 1.38 | 0.72 | .05 |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 9: excluded from work activities/meetings | 1.31 | 0.68 | .45** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 10: threatened if challenged wrongs | 1.17 | 0.51 | .09 |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment 11: hit/pushed/grabbed/threw at you | 1.07 | 0.31 | .74** |

| Positive Job Experiences 1: treated as an equal | 2.89 | 0.43 | .23** |

| Positive Job Experiences 2: praised for doing a good job | 2.84 | 0.48 | .13 |

| Positive Job Experiences 3: included enjoyable joking | 2.88 | 0.44 | .12 |

| Positive Job Experiences 4: told valuable to organization | 2.57 | 0.74 | .25** |

| Latent Indicators | |||

| Job Stress T1 1 | 2.17 | 1.33 | .71** |

| Job Stress T1 2 | 2.29 | 1.25 | .63** |

| Job Stress T1 3 | 1.99 | 1.37 | .54** |

| Job Stress T2 1 | 2.16 | 1.34 | .70** |

| Job Stress T2 2 | 2.26 | 1.28 | .61** |

| Job Stress T2 3 | 1.96 | 1.40 | .53** |

| Mental Health T1 1 | 3.04 | 0.65 | .57** |

| Mental Health T1 2 | 3.35 | 0.60 | .69** |

| Mental Health T1 3 | 3.79 | 0.50 | .58** |

| Mental Health T1 4 | 3.14 | 0.69 | .53** |

| Mental Health T1 5 | 2.76 | 0.69 | .56** |

| Mental Health T2 1 | 3.08 | 0.64 | .58** |

| Mental Health T2 2 | 3.39 | 0.63 | .73** |

| Mental Health T2 3 | 3.78 | 0.51 | .56** |

| Mental Health T2 4 | 3.10 | 0.67 | .59** |

| Mental Health T2 5 | 2.77 | 0.69 | .56** |

N – 1,167.

p < .05

p < .01

2-Group Analysis

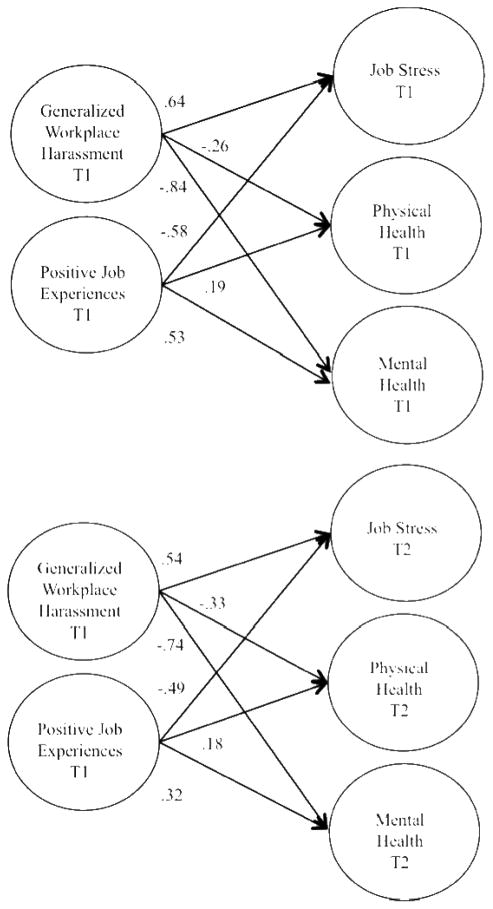

Results from testing the two-group structural model are summarized in Table 3. The CFI, NNFI, and RMSEA were .97, .94, and .02 respectively, and comply with Hu and Bentler’s (1999) empirically derived guidelines. There was no significant difference in the measurement models across groups (Δ χ2 = 13.1, df = 21, p = n.s.), while the structural models differed as expected (Δ χ2 = 15.3, df = 6, p <. 01). Figure 2 illustrates the standardized structural path estimates for Groups 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Model Comparisons

| Model | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δdf | CFI | NNFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | factor loadings & paths constrained | 785.9 | 391 | .969 | .941 | .021 | ||

| 2 | factor loadings unconstrained | 772.8 | 370 | 13.1 | 21 | .969 | .942 | .022 |

| 3 | factor loadings constrained & paths unconstrained | 770.6* | 385 | 15.3 | 6 | .979 | .952 | .02 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 2.

Two-group empirical model of generalized workplace harassment and positive job experiences’ effects on job stress and physical and mental health at Times 1 and 2. a

a All path loadings significant at p < .001.

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1 states that GWH is positively related to job stress at Time 1, with a weaker positive relationship at Time 2. Path estimates (see Table 4) reveal a positive relationship at Time 1 (.44, p < .001), and a weaker positive relationship at Time 2 (.06, p < .001). Comparisons of the standardized path estimates for Groups 1 and 2 (Figure 2) more vividly illustrate the noted influence and shifts in magnitude across time periods, and, moreover, results of a dependent beta z-test (Cohen & Cohen, 1983) shows this is a significant difference, z(1,167) = 2.115, p < .05. Hypothesis 1 is supported, demonstrating the dissipating effect of GWH on job stress over time.

Table 4.

Path Loadings

| Path | Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Generalized Workplace Harassment T1 --> Job Stress T1 | .44** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment T1 --> Job Stress T2 | .06** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment T1 --> Physical Health T1 | −.06** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment T1 --> Physical Health T2 | −.16** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment T1 --> Mental Health T1 | −.63** |

| Generalized Workplace Harassment T1 --> Mental Health T2 | −.26** |

| Positive Job Experiences T1 --> Job Stress T1 | −.10** |

| Positive Job Experiences T1 --> Job Stress T2 | −.08** |

| Positive Job Experiences T1 --> Physical Health T1 | .06** |

| Positive Job Experiences T1 --> Physical Health T2 | .37** |

| Positive Job Experiences T1 --> Mental Health T1 | .58** |

| Positive Job Experiences T1 --> Mental Health T2 | .07** |

| Job Stress T1 --> Job Stress T2 | .98** |

| Physical Health T1 --> Physical Health T2 | .60** |

| Mental Health T1 --> Mental Health T2 | .40** |

N = 1,167.

p < .05

p <. 01

Hypothesis 2 states that positive job experiences are positively related to mental health at Time 1, with a weaker positive relationship at Time 2. Path estimates indicate a positive relationship at Time 1 (.58, p < .001), and a weaker positive relationship at Time 2 (.07, p < .001). Figure 2 further illustrates this diminishing influence and a dependent beta z-test reveals this to be a significant difference, z(1,167) = 3.02, p < .001. Hypothesis 2 is supported, demonstrating the dissipating effects of positive job experiences on mental health over time. Hypothesis 3 predicts that GWH relates negatively to mental health at Time 1, and less so at Time 2. Path estimates reveal a negative relationship at Time 1 (−.63, p < .001), and a weaker negative relationship at Time 2 (−.26, p < .001). The results of a dependent beta z-test reveal this to be a significant difference, z(1,167) = −2.13, p<.01. Hypothesis 3 is supported, evidencing the dissipating effect of GWH on mental health over time.

Hypotheses 4 and 5 address differences between GWH and positive job experiences’ effects on mental health over time. Hypothesis 4 predicts that, in the short term, the negative relationship between GWH and mental health is stronger than the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health. Path estimates indicate that GWH is negatively related to mental health at Time 1 (−.63, p < .001), and that the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health is weaker (.58, p < .001). The results of a dependent beta z-test reveal this to be a significant difference, z(1,167) = −21.70, p < .001. Hypothesis 4 is supported, illustrating that, near the time they occur, GWH is more influential then positive job experiences on mental health. Hypothesis 5 states that, in the long term, the negative relationship between GWH and mental health is weaker than the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health. Path estimates indicate that GWH is negatively related to mental health at Time 2 (−.26, p < .001), but the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health was weaker (.07, p < .001), and the dependent beta z-test shows that this is a significant difference, z(1,167) = −19.68, p < .001. Hypothesis 5 is not supported. Figure 2 further illustrates the differing influences at Time 1 and Time 2 of GWH and positive job experiences on mental health.

Hypothesis 6 states that positive job experiences are positively related to physical health at Time 1, with a weaker positive relationship at Time 2. Path estimates reveal a positive relationship at Time 1 (.06, p < .001), and a stronger positive relationship at Time 2 (.37, p < .001). Hypothesis 6 is not supported. Hypothesis 7 states that GWH relates negatively to physical health at Time 1, with a weaker negative relationship at Time 2. Path estimates reveal a negative relationship at Time 1 (−.06, p < .001), and a stronger negative relationship at Time 2 (−.16, p < .001). Hypothesis 7 is not supported.

Hypothesis 8 states that, in the short term, the relationship between GWH and physical health will be stronger than the relationship between positive job experiences and physical health. Path estimates reveal a negative relationship between GWH and physical health at Time 1 (−.06, p < .001), and a similar relationship between positive job experiences and physical health (.06, p < .001). Hypothesis 8 is not supported.

Hypothesis 9 states that the relationship between GWH at Time 1 and physical health at Time 2 is weaker than the relationship between positive job experiences at Time 1 and physical health at Time 2. Path estimates reveal a negative relationship between GWH and physical health at Time 2 (−.16, p < .001), and a stronger positive relationship between positive job experiences and physical health (.37, p < .001), and the dependent beta z tests show this is a significant difference, z(1,167) = −7.94, p < .001. Hypothesis 9 is supported, demonstrating that the effects of GWH over time persist and are more influential on physical health than are positive job experiences.

In general, the model supported the proposed short- and longer-term influences of GWH and positive job experiences on focal outcomes after controlling for carryover effects on focal outcomes from Time 1 to Time 2. Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4 were supported. Hypothesis 5 (the long-term relationship between GWH and mental health predicted to be weaker than the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health), was not supported. And, whereas Hypotheses 6, 7, and 8, all dealing with physical health were not supported, Hypothesis 9, (predicting a greater cross-lagged influence of positive job experience on physical health than the cross-lagged influence of GWH on physical health) was supported. We address these findings more fully in the Discussion below.

Discussion

An initial motivation for this research was to investigate the concurrent influence of positive and negative factors on employee well-being, and our findings of complementary and/or contrasting influences from GWH and positive job experiences on job stress, physical health and mental health allow us to consider that objective fulfilled. In addition, we find that mobilization-minimization mechanisms do operate within individuals in organizations, mainly when the outcome of interest is mental health. In Hypotheses 1 and 3, we find evidence that GWH is detrimental to employee well-being but the effect dissipates over time. We also support (in Hypotheses 2 and 4) that positive job experiences weigh positively on mental health in the short-term and less so in the long-term, and that in the short-term GWH has a stronger influence on mental health than do positive job experiences. It appears that employees mobilize more in response to negative events than positive ones as the theory prescribes. The second part of the theory, however, that mobilization would be minimized at a faster rate for negative as compared to positive influences (Hypothesis 5) was not supported. After a year, the relationship between GWH and mental health was not weaker than the relationship between positive job experiences and mental health. GWH’s effect on mental health was reduced, but not to the extent that the effect was less than that of positive job experiences. Apparently, the mobilization, that is, arousal effects, of GWH are salient and prolonged such that they not only weigh more heavily on workers than positive job experiences, but they also stay with workers mentally for periods longer than one year.

Hypotheses 6 through 9 all dealt with physical health outcomes of GWH and positive job experiences. Hypothesis 6 detailed a dissipation effect of positive job experiences on physical health over time, but the results point to a slightly larger influence at Time 2 (although not statistically significant) and do no support the hypothesis. Likewise, Hypothesis 7 predicted a dissipation of the negative influence of GWH on physical health and was not supported, as our results show a significantly larger influence of GWH on physical health at Time 2 than at Time 1. One possible explanation for these results is that the full influence of GWH and positive job experiences may take longer than a year to fully mature, which is not altogether implausible given the cumulative nature of many physical ailments. The mixed results suggest that additional research is needed into the influence of GWH and positive job experiences on physical health. In the least, our study suggests that their influences on mental versus physical health seem to be very different. Hypotheses 8 and 9 predicted asymmetrical short-term and long-term effects of GWH and positive job experiences, with negative effects being stronger in the short term (H8) and positive effects having a slower rate of dissipation and being stronger than the relationship of GWH to physical health in the long term (H9). As discussed in the context of Hypotheses 6 and 7, the influence of GWH on physical health for our sample seemed to have a gestation and influence period longer than a year, resulting in its influence being roughly of the same magnitude as that of positive job experiences in the short term (no support for H8). Given the fact that our expectations for differential influences on mental health were supported, we attribute the lack of support for Hypotheses 6 through 8 to one year perhaps not being long enough for the mobilization and minimization processes of GWH influencing physical health to run their course. Or, by a lack of support for Hypothesis 6 and support for Hypothesis 9, there may be stronger, lasting effects when workers encounter positive job experiences. To determine which of these arguments prevail, longitudinal studies of longer than one year are needed.

If it is found that positive job experiences do stay with employees longer, and are more instrumental in determining physical health than is GWH (the latter is suggested by support for Hypothesis 9), this may be good news for scholars who subscribe to the positive organizational psychology movement. Leaders in organizations may reap employee physical health returns, and by extension lower healthcare costs, through organizational interventions designed to create positive psychosocial job experiences for those employees. Training supervisors in supportive behaviors such as coaching and encouragement may reap organizational returns. Unfortunately the results do not paint a similarly encouraging picture when the outcome of interest is mental health. We feel our finding that the effects of harassment persist longer than a year, and that these effects undermine positive job experiences’ effects on mental health is an important finding. While there has been more research on the long-term implications of job stress, there has been little research on the long-term effects of dysfunctional organizational behavior such as workplace incivility, abusive supervision, and GWH. Research concerning these constructs is relatively in its infancy, and has been consumed with demonstrating the host of negative outcomes that result, with little focus on specifying the duration of which workers will experience these outcomes. We feel our study has taken a requisite step in that direction.

Practical Implications

A lesson for managers from this research may be that it is best to deal with GWH issues as soon as possible after occurrence. It appears that their effects on employees’ mental health are most destructive at the time they occur. Attentive managers who are attune to negative workplace events may do well to be ready with suggestions of the proper deployment of company resources, such as employee assistance programs, to aid in protecting and restoring employee mental health. They are also advised to minimize the incidence of workplace harassment on both humane and economic grounds, given the adverse effects of compromised mental and physical health for employees and companies. On the other hand, managers should consider underscoring employees’ positive job experiences in both formal (e.g., performance appraisals) and informal (e.g., seizing opportunities for coaching) ways, because of the positive and long-term effect such actions can have on employee well-being.

Strengths

Two strengths of this study lie in its longitudinal tracking of a large national sample representing a wide variety of occupations, and concurrent measurement of both positive and negative events in the workplace. We find support for the mobilization-minimization hypothesis as it pertains to negative and positive factors in organizations when it comes to job stress and mental health, and support for mobilization when it comes to physical health with a plausible explanation for these effects lingering past the one year mark. A third contribution stems from an operationalization of GWH and positive job experiences that is more in line with their respective theoretical underpinnings and the demands of true score theory. We add empirical support to the theoretical arguments for modeling both GWH and positive job experiences as formative constructs, given that their respective “indicators as a group, jointly determine the conceptual and empirical meaning of the construct” (Jarvis et al., 2003), and the constructs’ make-up can and should vary across respondents. One possibility for future research is to compare the predictive and explanatory power of formative and reflective articulations of these constructs to better assess their true nature and value added.

Limitations

Our research is not without limitations. First, we framed our test of “the good and bad” in terms of positive job experiences and generalized workplace harassment. However, we know that what is thought of as “good and bad” is largely culturally determined (Fineman, 2006), and in the case of this research heavily influenced by Western culture. Our positive job experiences included those that may be perceived as affirmative in individualist cultures (e.g., being praised for accomplishments, and being treated as an equal). Likewise, in higher power distance cultures, our conceptualization of GWH (e.g., “told my ideas were unwanted,” “given the silent treatment”) may be more acceptable behavior and hence less detrimental for victims. As a result this study’s generalizability to non-Western workers cannot be established.

A second limitation involves our lack of equivalent measures of both positive job experiences and generalized workplace harassment at Time 2, in order to determine how changes in these experiences in the intervening year may have influenced Time 2 outcomes. We did empirically account (in part) for carryover effects and changes in work conditions by allowing the error terms for the latent variables to correlate. While prior research has indicated that generalized workplace harassment experiences tend to be fairly stable over a one year time period (see Rospenda, Richman, Wislar, & Flaherty, 2000), we were unable to locate any comparable research looking at continuity or change in these specific positive job experiences. Thus, we can not be certain that changes in positive and negative experiences from Time 1 to Time 2 did not occur, and if we had incorporated change in our model, this may have affected our outcomes differently. For example, in the sexual harassment literature, Munson, Hulin, and Drasgow (2000) found that changes in job satisfaction mirrored changes in sexual harassment in a two-year period following initial assessment; female university employees experiencing sexual harassment at time 2 but not time 1 had decreased job satisfaction, and those experiencing sexual harassment at time 1 but not time 2 had increased job satisfaction. Future research on the relative effects of positive and negative job experiences may wish to utilize full two-wave panel designs for longitudinal studies, such as those advocated by Zapf, Dormann, and Frese (1996), to more rigorously assess how changes in job experiences affect job, mental health, and physical outcomes over time.

Third, several moderators of the influence of GWH and positive job experiences remain unexamined. Research has found, for example, that positive events are not experienced as intensely because people feel more in control (Mandler, 1975; 1984). With negative emotions, it is the sense of low control that produces greater arousal. Investigations which test the moderating influence of control on the relationships proposed here are warranted. Fourth, while the final sample size was large, the overall response rate for both waves of the study was relatively low, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results. Finally, another limitation of our sample concerns attrition and bias. Sample demographics show that respondents who did not respond at time 2 were more likely to be minorities, have lower levels of education and income, and be younger. This not only limits the generalizability of the results, but also highlights the possibility that at-risk groups may be systematically excluded by currently popular and accepted research methods. At a minimum, future research should consider oversampling from among these groups, as well as making a special effort to retain respondents from such groups in future studies (see Yancey, Ortega, & Kumanyika, 2006 for a detailed review of strategies to improve recruitment and retention of minority research participants).

Conclusion

Our longitudinal study of a national sample of 1,167 workers supports the modeling of concurrent positive and negative workplace experiences’ effects on employee stress and well-being. The study lends support to the idea that both are important and contribute to important employee outcomes in their own right and together, and to the notion that researchers would do well to acknowledge both positive and negative factors in future research. We realize that current research methodologies make it difficult to control for all individual and organizational factors that may play a role in the relationships between variables under study. However, we feel that this research underscores the need to more carefully tailor studies to represent the realities of work life. As least when it comes to well-being, it is not just the bad boss or the supportive coworker (that is the bad or the good) who serve to determine workers’ health and well-being—the factors are many. Moreover, researchers may find that previous studies that have employed a “one-eyed view of the social world” (Fineman, 2006, p. 275) may provide a biased understanding of multi-faceted workplace experiences. Future research designs that control for, if not model, how “the good and the bad” influence one another, and influence other outcomes when they co-occur, may be most beneficial.

Footnotes

Data for this study are from a large National Institute of Health study on workplace harassment, life and job stressors, coping, and health outcomes. The grant was awarded to one of the authors.

Contributor Information

Jenny M. Hoobler, University of Illinois at Chicago

Kathleen M. Rospenda, University of Illinois at Chicago

Grace Lemmon, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Jose A. Rosa, University of Wyoming

References

- Andersson LM, Pearson CM. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review. 1999;24:452–471. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 7.0 software. Spring House, PS: Amos Development Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B. Petty tyranny in organizations. Human Relations. 1994;47:755–778. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi RP. Structural equation modeling in marketing research: Basic principles. In: Bagozzi RP, editor. Principles of Marketing Research. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers Inc; 1994. pp. 317–385. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. Multitrait-multimethod matrices in consumer research: Critique and new developments. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 1993;2:143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RJ, Robinson SL. The past, present, and future of workplace deviance research. In: Greenberg J, editor. Organizational behavior: The state of the science. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 247–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bird CE, Fremont AM. Gender, time use and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:114–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling NA, Beehr TA. Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:998–1012. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn N. The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago: Aldine; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner J. Self-esteem at work. Lexington, MA: D.D. Heath & Co; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, McGill KL. The cost of good fortune: When positive life events produce negative health consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1103–1110. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS Graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:272–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Bernston GG, Gardner WL. The affect system has parallel and integrative processing components: Form follows function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:839–855. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LH, McGowan J, Fooskas S, Rose S. Positive life events and social support and the relationship between life stress and psychological disorder. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1984;12:567–587. doi: 10.1007/BF00897213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Turner RB, Alper CM, Skoner DP. Emotional style and susceptibility to the common cold. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:652–657. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077508.57784.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortina LM, Magley VJ, Williams JH, Langhout RD. Incivility at the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2001;6:64–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox H. Verbal abuse nationwide, part II: Impact and modification. Nursing Management. 1991;22:66–69. doi: 10.1097/00006247-199103000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AR, Sherbourne CD, Peterson JR. Scoring manual: Adult health status and patient satisfaction measures used in RAND’s Health Insurance Experiment. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 1988. (No. N-2190-HHS) [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. In: Higgins E, Kruglanski A, editors. Motivational science: Social and personality perspectives. Key readings in social psychology. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2000. pp. 128–145. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:542–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MK, Ganster DC, Pagon M. Social undermining in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal. 2002;45:331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton J, Dukerich J. Keeping an eye on the mirror: The role of image and identity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal. 1991;34:517–554. [Google Scholar]

- Eby L, Butts M, Lockwood A, Simon SA. Protégé’s negative mentoring experiences: Construct development and nomological validation. Personnel Psychology. 2004;57:411–447. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman S. On being positive: Concerns and counterpoints. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31:270–291. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald LF, Drasgow F, Hulin CL, Gelfand MJ, Magley VJ. Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82:578–589. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden- and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Joiner T. Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science. 2002;13:172–175. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B, Losada M. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist. 2005;60:678–686. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, Larkin GR. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:365–376. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French JRP, Jr, Kahn RL. A programmatic approach to studying the industrial environment and mental health. Journal of Social Issues. 1962;18:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL, Reis HT, Elliott AJ. Behavioral activation and inhibition in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:1135–1149. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D, Fitzwater E, Succop P. Relationships of stressors, strain, and anger to caregiver assaults. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2003;24:775–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner BA, Krause N, Ragland DR, Fisher JM. Objective stress factors, accidents, and absenteeism in transit operators: A theoretical framework and empirical evidence. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1998;3:130–146. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1975;55:259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben JRB, Osburn HK, Mumford MD. Action research as a burnout intervention. Reducing burnout in the federal fire service. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2006;42:244–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hall AT, Royle MT, Brymer RA, Perrewe’ PL, Ferris GR, Hochwarter WA. Relationships between felt accountability as a stressor and strain reactions: The neutralizing role of autonomy across two studies. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11:87–99. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KJ, Kacmar MK. Easing the strain: The buffer role of supervisors in the perceptions of politics-strain relationship. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology. 2005;78:337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Hart PM, Wearing AJ, Headey B. Assessing police work experiences: Development of the Police Daily Hassles and Uplift Scales. Journal of Criminal Justice. 1993;21:553–572. [Google Scholar]

- Headey B, Wearing AJ. Understanding happiness: A theory of subjective well-being. Melbourne, Australia: Longman Cheshire; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Heuven E, Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Huisman N. The role of self-efficacy in performing emotion work. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2006;69:222–235. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell JJ, Jr, Murphy LR. An overview of occupational stress and health. In: Rom WM, editor. Environmental and occupational medicine. 2. Boston: Little Brown; 1992. pp. 675–684. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell JJ, Jr, Nelson DL, Simmons BL. Measuring job stressors and strains: Where we have been, where we are, and where we need to go. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1998;3:368–389. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PB. Specifying the buffering hypothesis: Support, strain and depression. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1992;55:363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis CB, Mackenzie SB, Podsakoff PM. A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research. 2003;30:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kanouse DE, Hanson LR. Negativity in evaluations. In: Jones EE, Kanouse DE, Kelley HH, Nisbett RE, Valins S, Weiner B, editors. Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press; 1972. pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Keashly L, Harvey S. Emotional abuse in the workplace. In: Fox S, Spector PE, editors. Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 201–235. [Google Scholar]

- Keashly L, Jagatic K. By any other name: American perspectives on workplace bullying. In: Einarsen S, Hoel H, Zapf D, Cooper CL, editors. Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and practice. London: Taylor & Francis; 2003. pp. 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Keashly L, Trott V, MacLean LM. Abusive behavior in the workplace: A preliminary investigation. Violence and Victims. 1994;9:341–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohan A, Mazmanian D. Police work, burnout, and pro-organizational behavior: A consideration of daily work experiences. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2003;30:559–583. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrakas PJ. Telephone survey methods: Sampling, selection, and supervision. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist. 1991;46:819–834. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.8.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Kanner A, Folkman S. Emotions: A cognitive phenomenological analysis. In: Plutchik R, Kellerman H, editors. Theories of emotions. New York: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lethbridge-Cejku M, Schiller JS, Bernadel L. DHHS Publication No. PHS 2004-1550. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinthal CF. Introduction to physiological psychology. 3. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Cortina LM. Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005;90:483–496. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Cortina LM, Magley VJ. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008;93:95–107. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord FM, Novick MR. Statistical theories of mental test scores. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King LA, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler G. Mind and emotion. New York: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler G. Mind and body: Psychology of emotion and stress. New York: Norton; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GD, Zimbardo PG. Affective consequences of inadequately explained physiological arousal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:970–988. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Dynamics of personality organization, I. Psychological Review. 1943;50:514–539. [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE., Jr Construction and validation of an alternate form general mental health scale for the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-Item Health Survey. Medical Care. 1995;33:15–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson LJ, Hulin CL, Drasgow F. Longitudinal analysis of dispositional influences and sexual harassment: Effects on job and psychological outcomes. Personnel Psychology. 2000;53:21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Niedhammer I, David S, Degioanni S. Association between workplace bullying and depressive symptoms in the French working population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun M, George L. Physician and self ratings of health, neuroticism and subjective well-being among men and women. Personality and Individual Differences. 1984;5:533–539. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary-Kelly AM, Griffin RW, Glew DJ. Organization-motivated aggression: A research framework. Academy of Management Review. 1996;21:225–253. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters G, Czapinski J. Positive-negative asymmetry in evaluations: The distinction between affective and informational negativity effects. European Review of Social Psychology. 1990;1:33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MG, Rosa JA. Transforming work-family conflict into commitment in network marketing organizations. Academy of Management Journal. 2003;46:395–417. [Google Scholar]

- Richman JA, Fendrich M, Wislar JS, Flaherty JA, Rospenda KM. Effects on alcohol use and anxiety of the September 11, 2001 attacks and chronic work stressors: A longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:2010–2015. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LM. Shifting the lens on organizational life: The added value of positive scholarship. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31:292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KC. Detrimental aspects of social relationships: Taking stock of an emerging literature. In: Veil H, Baumann U, editors. The meaning and measurement of social support. New York: Hemisphere; 1992. pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rospenda KM, Richman JA. The factor structure of generalized workplace harassment. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:221–238. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.2.221.64097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rospenda KM, Richman JA. Harassment and discrimination. In: Barling J, Kelloway EK, Frone MR, editors. Handbook of Work Stress. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 149–188. [Google Scholar]

- Rospenda KM, Richman JA, Ehmke JLZ, Zlatoper KW. Is workplace harassment hazardous to your health? Journal of Business and Psychology. 2005;20:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rospenda KM, Richman JA, Wislar JS, Flaherty JA. Chronicity of sexual harassment and generalized workplace abuse: Effects on drinking outcomes. Addiction. 2000;95:1805–1820. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9512180510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salancik GR, Pfeffer J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1978;23:224–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders P, Huynh A, Goodman-Delahunty J. Defining workplace bullying behaviour: Professional lay definitions of workplace bullying. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2007;30:340–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist. 2000;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. History and present status of the stress concept. In: Lazarus RS, Monat A, editors. Stress and coping: An anthology. New York: Columbia University Press; 1985. pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton JM, Balzer WM, Smith PC, Parra LF, Ironson G. A general measure of work stress: The Stress in General Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:866–888. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization- minimization hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:67–85. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper BJ. Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal. 2000;43:178–190. [Google Scholar]