Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease in which inflammatory lesions lead to tissue injury in the brain and/or spinal cord. The specific sites of tissue injury are strong determinants of clinical outcome in MS, but the pathways that determine whether damage occurs in the brain or spinal cord are not understood. Previous studies in mouse models of MS demonstrated that IFN-γ and IL-17 regulate lesion localization within the brain, however, the mechanisms by which these cytokines mediate their effects have not been identified. Here we show that IL-17 promoted, but IFN-γ inhibited, ELR+ chemokine-mediated neutrophil recruitment to the brain, and that neutrophil infiltration was required for parenchymal tissue damage in the brain. In contrast, IFN-γ promoted ELR+ chemokine expression and neutrophil recruitment to the spinal cord. Surprisingly, tissue injury in the spinal cord did not exhibit the same dependence on neutrophil recruitment that was observed for the brain. Our results demonstrate that the brain and spinal cord exhibit distinct sensitivities to cellular mediators of tissue damage, and that IL-17 and IFN-γ differentially regulate recruitment of these mediators to each microenvironment. These findings suggest an approach toward tailoring therapies for patients with distinct patterns of neuroinflammation.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) believed to be mediated by myelin-specific T cells. The majority of patients with MS have lesions disseminated in the brain, and some have accompanying spinal cord lesions. Interestingly, a subset of patients have lesions restricted primarily to the spinal cord and optic nerves, termed opticospinal MS. The clinical signs of disease reflect the site of lesion localization and the nature of these clinical signs can significantly impact the extent of disability and prognosis. It is important to determine if different pathogenic mechanisms contribute to these distinct inflammatory patterns as this may suggest a need for individualized therapeutic approaches.

MS is widely studied using experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis(EAE), which is induced by immunization with myelin antigens or by adoptive transfer of myelin-specific T cells. Unlike the majority of MS patients, lesions are predominantly localized in the spinal cord in most rodent EAE models. Disease in these models is manifested by ascending flaccid paralysis, referred to as “classic” EAE. However, some“ atypical” EAE models have been described that exhibit head tilt, body lean, ataxia, spinning, or axial rotation indicative of inflammation in the brain (1–4). A typical EAE was observed in specific antigen/strain combinations (5–7), and in mice deficient in IFN-γ signaling (2, 4, 8, 9), suggesting that IFN-γ inhibits brain inflammation in EAE. While it is not known how IFN-γ deficiency promotes brain inflammation, the inflammatory infiltrate in the brain in these mice was often dominated by neutrophils (2, 8). Subsequently, we and others demonstrated that IL-17 signaling preferentially promotes brain inflammation (9–11). While IL-17 is known to induce ELR+ chemokines that recruit neutrophils, it has not been established that this is the mechanism by which IL-17 promotes brain inflammation. Defining the mechanisms and cell types that promote lesion formation in the brain parenchyma is especially relevant as the majority of patients with MS have lesions in this region.

We investigated how IL-17 and IFN-γ differentially influence brain versus spinal cord inflammation in C3Heb/Fej mice that were wild-type (WT) or genetically deficient in IFN-γ and/or IL-17 signaling. We found that the critical activity mediated by these cytokines in the brain was their differential regulation of neutrophil recruitment. In the brain, IFN-γ suppressed, while IL-17 promoted, induction of the ELR+ chemokine CXCL2, which played the major role in neutrophil recruitment to this region. Importantly, we showed that neutrophils were required for tissue damage in the brain and development of atypical clinical signs. In stark contrast to their effects in the brain, we found that IFN-γ promoted and IL-17 was not required for CXCL2-induced neutrophil recruitment to the spinal cord. Strikingly, neutrophil depletion ameliorated atypical EAE but had no effect on classic EAE signs. Histochemical analyses confirmed that tissue injury in the spinal cord was much less dependent on neutrophil infiltration than the brain. The therapeutic implications of these findings were further supported by showing that atypical, but not classic, EAE signs were eliminated by administrating an antagonist for CXCR2, the major chemokine receptor for CXCL2 expressed on neutrophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C3HeB/FeJ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA). IL-17RA−/− mice generated by Amgen were obtained from Taconic and backcrossed onto the C3HeB/FeJ mice for at least 12 generations. IFN-γR−/− and GFAP-GFP transgenic mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and backcrossed onto the C3HeB/FeJ background for at least 12 generations. Mice used for EAE induction were between 6 and 10 weeks of age. All procedures have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Washington.

Protein and peptides

Recombinant rat MOG protein (rMOG; residues 1–125), was produced in Escherichia coli and purified as previously described (12). MOG97–114 peptide (rat sequence, TCFFRDHSYQEEAAVELK) was purchased from GenScript.

EAE induction

EAE was induced by culturing splenocytes (1 × 107 cells/ml) from rMOG-immunized mice for 3 d with 5 μg/ml MOG97–114 peptide and 10 ng/ml rIL-23 (eBioscience). Viable cells were isolated from a lympholyte gradient (Cedarlane) and intraperitoneally injected (2 × 107cells per mouse) into sublethally irradiated (250 rad) mice. The severity of EAE was scored as follows (a grade was assigned when any one of its associated signs was observed): grade 1, paralyzed tail, hindlimb clasping; grade 2, head tilt, hindlimb weakness; grade 3, one paralyzed leg, mild body leaning; grade 4, two paralyzed legs, moderate body leaning; grade 5, forelimb weakness, severe body leaning; grade 6, hunched, breathing difficulty, body rolling; grade 7, moribund. Atypical EAE was determined by the presence of one or more of the following symptoms: head tilt, body leaning, or body rolling.

Isolation of CNS cells

Mononuclear cells were isolated from the CNS of perfused EAE mice, as previously described (13). Briefly, brain and spinal cord were dissociated with a 5-ml syringe plunger through a sterile stainless steel mesh and centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm. Cell pellets were resuspended in 30% Percoll, overlaid onto 70% Percoll, and centrifuged without brake for 20 min at 2400 rpm. Cells were collected from the 30–70% Percoll interface. For cell sorting experiments, cells were isolated from the CNS of perfused mice by digesting brains or spinal cords with 0.5 mg/mL papain (Worthington Biochemical) and 20 ng/ml DNase in HBSS for 20 minutes at 37ºC prior to isolating the cells on a Percoll gradient.

Flow cytometry

Cells were incubated with Fc block (clone 2.4G2; eBioscience) in normal mouse serum for 15 min at 4°C, washed, and stained with antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. Antibody specificity, fluorochrome, clone name and vendor were as follows: CD4-APC(clone GK1.5), CD45-PacBlu (clone 30-F11) and CD11b-PECy7(M1/70) were from eBioscience; IFN-γ-FITC(clone XMG1.2), IL-17-PCPCy5.5 (clone TC11–18H10), TCR-APC-Cy7 (clone H57–597), Ly6G-FITC (clone 1A8), Ly6C-PCPCy5.5 (clone HK1.4), and CD31-APC(clone MEC 13.3) were from BD Biosciences. Cells were analyzed using a FACS Canto cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software version 8.8.7 (Tree Star).

qPCR

Tissue samples: Brain and spinal cord tissues were harvested from perfused naïve mice or mice with EAE (1–3 days post-onset, grade ≥ 3) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Messenger RNA was extracted using RNeasy midi (brain tissue) or mini (spinal cord tissue) kits from Qiagen and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II (Invitrogen). qPCR was performed on an ABI 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized to values for B-actin.

Purified cells: cells were sorted from the brains and spinal cords separately of naïve mice and mice with EAE (1–3 days post-onset, grade ≥ 3) using a FACS ARIA (BD Biosciences). Astrocytes were sorted from GFAP-GFP transgenic mice as CD45−GFP+cells and endothelial cells were sorted based on CD31 expression. Microglia and the subset of cells containing macrophages, monocyte and dendritic cells were sorted based on expression of CD45 and CD11b as previously described (14). cDNA was generated using a Power SYBR® Green Cells-to-CT™ Kit (life technologies). Quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI ViiA 7 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized to values for GAPDH.

In vivo treatments during EAE

The neutrophil-depleting antibody anti-Ly6g (clone 1A8) and isotype control antibody (clone 2A3) were purchased from Bio-X-Cell (West Lebanon, NH). Beginning on the day of T cell transfer, either 200 μg anti-Ly6G or isotype control (clone 2A3) was administered by intraperitoneal injection every other day until time of sacrifice (typically 7–8 days post-transfer). SB332235, the small molecule competitive antagonist of CXCR2 provided by GlaxoSmithKline (500 μg dissolved in 200 μL H20), or vehicle control (H20) was administered to mice by oral gavage 2–3 times daily beginning on day of T cell transfer and continued until time of sacrifice (typically 7–8 days post-transfer).

Histochemical Analysis

Brains and spinal cords from mice with EAE were preserved in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were examined by a board-certified veterinary pathologist who was blinded to group assignments. The total sectional tissue area of multiple brain and cord sections from each mouse and the area of each focal, aggregated inflammatory/necrotic lesion within each section were measured using Nikon NIS-Elements software and expressed as percent of total brain or spinal cord. Numbers of vessels cuffed by inflammatory cells within each section were also counted and normalized to total tissue area. Included in the analysis was a semi-quantitative assessment of character and severity of tissue injury (manifested by necrotic and apoptotic cell death coupled with inflammatory cell accumulation graded on an inclusive scale of 1+ minimal to 4+ maximal injury).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software), using an unpaired two-tailed Student t test or χ-square test. A p value <0.05 was considered significantly different.

RESULTS

IL-17 and IFN-γ signaling differentially affect clinical manifestation of EAE

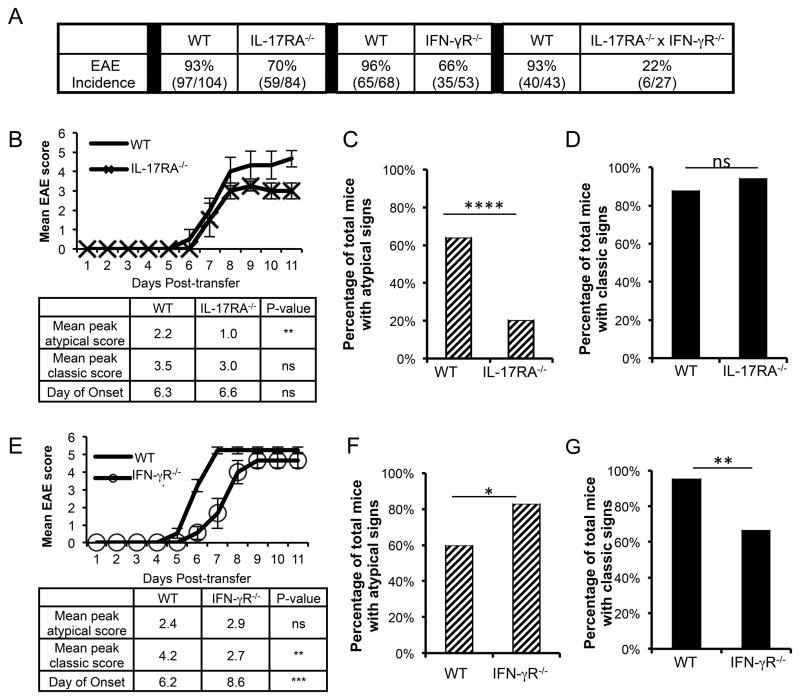

We previously showed that WT C3Heb/Fej mice develop a typical EAE with or without accompanying classic EAE signs following adoptive transfer of Th17-skewed myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-specific T cells (10). Here we developed genetic models to define the mechanisms by which IL-17 and IFN-γ signaling determines lesion localization and clinical manifestation of EAE. EAE was induced by transferring CD4+T cells from WT MOG-immunized mice into WT, IL-17 receptor A−/−(IL-17RA−/−), IFN-γ receptor alpha chain −/−(IFN-γ R−/−), or IL-17RA−/− x IFN-γ R−/− double knock-out mice. The transferred T cells were skewed in vitro by incubation with IL-23 prior to transfer (Th17:Th1 ratio ~2:1) to predispose the WT recipients toward atypical EAE and to bypass any potential effects of IL-17 or IFN-γ signaling on development or priming of myelin-specific T cells. In mice deficient in both cytokine receptors, EAE incidence was reduced to 22% (6/27) compared to 93% (97/104) for WT mice. In contrast, EAE incidence was only modestly reduced in both IL-17RA−/− mice and IFN-γR−/− mice (Fig. 1A). Importantly, deficiency in either cytokine receptor alone significantly impacted the clinical manifestation of disease. In IL-17RA−/− mice that developed EAE, both the severity and incidence of atypical signs was sharply reduced compared to WT mice(Fig. 1 B, C), supporting our previous finding that IL-17 signaling promotes atypical EAE (10). However, the severity and incidence of classic EAE signs among these same mice was unchanged (Fig. 1B, D). In contrast, IFN-γ R−/− recipients of IL-23-skewed T cells demonstrated similar severity but increased incidence of atypical EAE signs compared to WT mice(Fig. 1E, F), consistent with other reports that IFN-γ signaling inhibits the incidence of brain inflammation (2, 4, 9). Interestingly, both the severity and incidence of classic EAE in these same mice was significantly reduced compared to WT recipients (Fig. 1E, G), supporting the notion that IFN-γ promotes inflammation in the spinal cord (2, 4), despite its inhibitory effect in the brain. Collectively, these data indicate that both IL-17 and IFN-γ signaling promote overall EAE development, but do so by differentially influencing the development of atypical versus classic EAE signs.

FIGURE 1. IL-17 and IFN-γ signaling influence clinical manifestation of EAE.

(A) Overall incidence of disease is shown for EAE induced by adoptive transfer of IL-23-skewed WT T cells into wild-type (WT), IL-17RA−/−, IFN-γR−/− and IL-17RA−/− xIFN-γ R−/− recipients. The number of WT mice used as controls for transfers into recipients of each genetic backgrounds is indicated. (B) Representative disease course for 5 IL-17RA−/− and 6 WT recipients is shown (top) and clinical characteristics are summarized for all 59 IL-17RA−/− and 97 WT control recipients with EAE (bottom). Clinical data are compiled from 8 independent experiments. (C) The percentage of mice with EAE that exhibited atypical clinical signs with or without accompanying classic clinical signs is shown for the 59 IL-17RA−/− and 97 WT control recipients. (D) The percentage of the same mice shown in (C) that exhibited classic EAE signs with or without accompanying atypical EAE signs is shown. (E) Representative disease course for 9 IFN-γ R−/− and 13 WT recipients is shown and clinical characteristics are summarized for all 35 IFN-γ R−/− and 65 WT control recipients with EAE. Data are compiled from 4 independent experiments. (F) The percentage of mice that exhibited atypical clinical signs with or without accompanying classic signs is shown for the 35 IFN-γ R−/− and 65 WT control recipients with EAE.(G) The percentage of the same mice shown in (F) that exhibited classic EAE signs with or without accompanying atypical EAE signs is shown. NS, not significant; * P< .05; ** P< .01; **** P< .0001.

IFN-γ and IL-17 differentially regulate neutrophil recruitment to the brain and spinal cord via opposing effects on CXCL2 expression

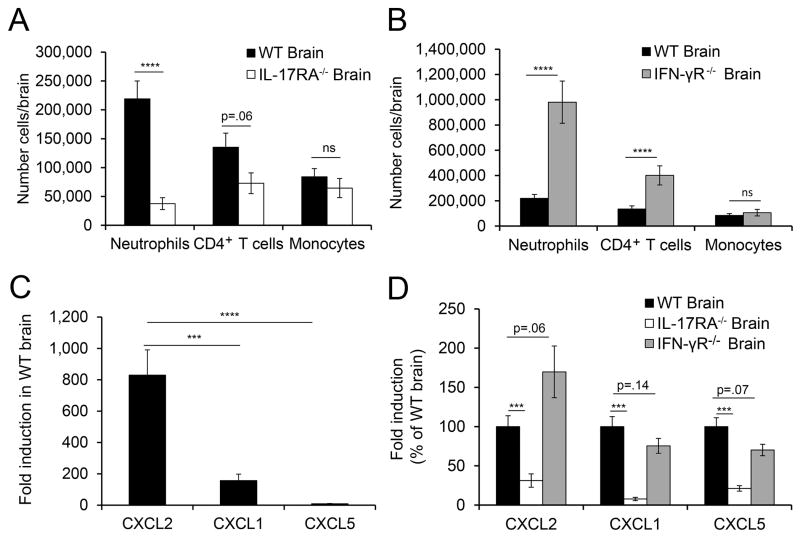

To define the mechanisms by which IL-17 and IFN-γ signaling exert opposite effects on induction of brain inflammation, we analyzed the inflammatory infiltrate in the brains of WT, IL-17RA−/− and IFN-γ R−/− mice at peak disease. Peak disease occurred 7–8 days post-transfer for WT and IL-17RA−/− mice and 7–10 days post-transfer in IFN-γ R−/− mice. On each genetic background, the kinetics (onset and progression) of atypical and classic EAE signs were similar. The gating strategy used to identify each cell subset is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. In the brain, the inflammatory monocyte number (CD45+CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6gG− cells) was similar in WT, IL-17RA−/− and IFN-γR−/− recipients even when the mice exhibited only classic signs(Fig. 2 A,B). In contrast, the number of neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+cells) was significantly decreased in IL-17RA−/− recipients (Fig. 2A) and significantly increased in IFN-γR−/− mice (Fig. 2 B), correlating with the incidence of atypical signs in these mice. CD4+T cell number strended lower in IL-17RA−/− mice but were significantly increased in IFN-γR−/− recipients (Fig. 2A,B), again correlating with the incidence of atypical EAE on each background. Interestingly, the CD4+T cell number was not decreased during preclinical disease (day 4 post-transfer) in the brains of IL-17RA−/− compared to WT mice (data not shown), indicating that initial CD4+T cell infiltration was not impaired by the absence of IL-17 signaling. Together, these data suggest that IL-17 signaling triggered by Th17 cells during preclinical disease is required for neutrophil recruitment to the brain, and that the opposing effects of IL-17 and IFN-γ on neutrophil recruitment correlate with subsequent T cell accumulation and manifestation of atypical EAE.

FIGURE 2. IL-17 signaling promotes, while IFN-γ signaling inhibits, neutrophil accumulation and CXCL2 induction in the brain.

(A)The absolute number of neutrophils (WT, n=23; IL-17RA−/−, n=10), CD4+T cells (WT, n=23; IL-17RA−/−, n=10), and inflammatory monocytes (WT, n=15; IL-17RA−/−, n=6) are shown for cells isolated from the brains of WT and IL-17RA−/− mice with EAE ≥ grade 3. Data are compiled from 2–7 independent experiments. (B) The absolute number of neutrophils (WT, n=23; IFN-γ R−/−, n=13), CD4+T cells (WT, n=23; IFN-γ R−/−, n=11), and inflammatory monocytes (WT, n=15; IFN-γ R−/−, n=7) are shown for cells isolated from the brains of WT and IFN-γ R−/− mice with EAE ≥ grade 3. Data are compiled from 3–7 independent experiments. (C) Fold induction of CXCL2 (n=13), CXCL1 (n=13), and CXCL5 (n=23) was determined by quantitative PCR in the brains of WT mice with EAE compared to healthy control mice. Data are compiled from 4–5 independent experiments. (D) Fold induction of CXCL2 (WT, n=13; IL-17RA−/−, n=6; IFN-γ R−/−, n=11), CXCL1 (WT, n=13; IL-17RA−/−, n=6; IFN-γ R−/−, n=12), and CXCL5 (WT, n=21; IL-17RA−/−, n=8; IFN-γ R−/−, n=9) was determined by quantitative PCR from brains of mice with EAE compared to healthy control mice, and expressed as a percent of the induction seen in WT mice with EAE within the same experiment. Data are compiled from 2–3 independent experiments. NS, not significant; *** P<.001; **** P<.0001.

We investigated the mechanism by which IL-17 and IFN-γ exert their disparate effects on neutrophil recruitment by analyzing the expression of ELR+ chemokines in the brains of IL-17RA−/− and IFN-γ R−/− mice. ELR+ chemokines attract neutrophils to inflamed tissues and are induced in response to inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 and IL-1β (15). We found that CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL5 were induced in WT brains of mice with EAE compared to healthy brains, with CXCL2 induced to the greatest extent (Fig. 2C). As expected, expression of CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL5 was significantly decreased in the brains of IL-17RA−/− mice (Fig. 2D). Unexpectedly, IFN-γ appeared to exert the opposite effect as CXCL2 expression trended higher in the brains of IFN-γR−/− mice (Fig. 2D), which may account for the greater accumulation of neutrophils in the brain of IFN-γR−/− compared to WT mice. Thus, the differential recruitment of neutrophils to the brain in IL-17RA−/− versus IFN-γ R−/− mice correlates with an essential role for IL-17 in promoting CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL5 expression as well as a potentially inhibitory effect of IFN-γ signaling on CXCL2 expression.

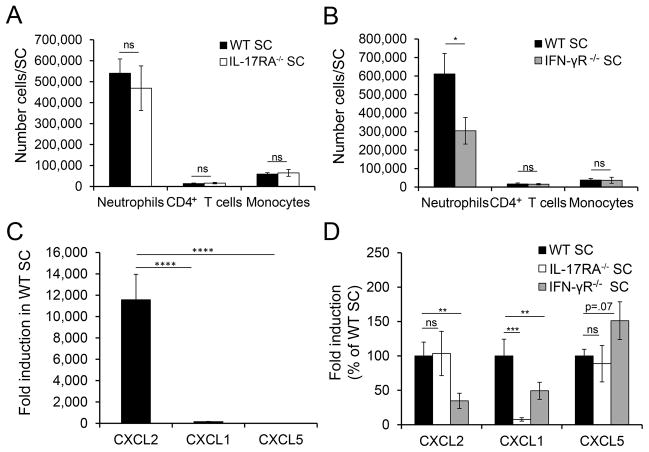

Our observations that atypical EAE correlated with neutrophil recruitment and that atypical but not classic EAE was decreased in IL-17RA−/− mice suggested that neutrophil recruitment to the spinal cord may not depend on IL-17 signaling. Indeed, we found no difference in neutrophil number in spinal cords of WT and IL-17RA−/− mice with EAE (Fig. 3 A), in contrast to our results for the brain. Surprisingly, neutrophil numbers were significantly reduced in IFN-γR−/− compared to WT mice (Fig. 3 B). Thus, IFN-γ signaling promotes neutrophil recruitment to the spinal cord but inhibits neutrophil influx into the brain. Analyses of ELR+ chemokine expression in the spinal cord during EAE in WT mice demonstrated that, as seen in the brain, CXCL2 induction was much greater than CXCL1 or CXCL5; furthermore, its induction was 10-fold greater in the spinal cord compared to the brain (Fig. 3C). CXCL2 was induced to comparable levels in the spinal cords of IL-17RA−/− and WT mice (Fig. 3D), consistent with the comparable neutrophil infiltration seen in the spinal cords but not brains of these mice. Importantly, CXCL2 induction was significantly decreased in the spinal cord of IFN-γR−/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 3D), indicating that IFN-γ signaling promotes CXCL2 induction in the spinal cord in WT mice. Differences between the small induction of CXCL1 and CXCL5 seen in WT EAE mice and their induction in IL-17RA−/− and IFN-γR−/− mice did not correlate with neutrophil recruitment in the spinal cords of these mice. Thus, CXCL2 was induced in the spinal cord via an IL-17-independent but IFN-γ-dependent mechanism, and its induction correlated with neutrophil recruitment to this region in EAE.

FIGURE 3. IFN-γ signaling promotes CXCL2 induction and neutrophil accumulation in the spinal cord.

(A)The absolute number of neutrophils (W T, n=11; IL-17RA−/−, n=6), CD4+T cells (WT, n=11; IL-17RA−/−, n=6), and inflammatory monocytes (WT, n=3; IL-17RA−/−, n=3) are shown for cells isolated from the spinal cords (SC) of WT and IL-17RA−/− mice with EAE ≥ grade 3. Data are a compilation from 2–3 independent experiments. (B) The absolute number of neutrophils (WT, n=12; IFN-γ R−/−, n=13), CD4+T cells (WT, n=8; IFN-γ R−/−, n=14), and inflammatory monocytes (WT, n=8; IFN-γ R−/−, n=10) are shown for cells isolated from the SC of WT and IFN-γR−/− mice with EAE ≥ grade 3. Data are compiled from 2–3 independent experiments. (C) Fold induction of CXCL2 (n=21), CXCL1 (n=13), and CXCL5 (n=24) as determined by quantitative PCR in the SC of WT mice with EAE compared to healthy control mice. Data are compiled from 4–5 independent experiments. (D) Fold induction of CXCL2 (WT, n=21; IL-17RA−/−, n=8; IFN-γ R−/−, n=6), CXCL1 (WT, n=13; IL-17RA−/−, n=4; IFN-γ R−/−, n=6) and CXCL5 (WT, n=24; IL-17RA−/−, n=6; IFN-γ R−/−, n=6) was determined by quantitative PCR in the SC of mice with EAE compared to healthy control mice, and expressed as a percent of the induction seen in WT mice with EAE within the same experiment. Data is a compiled from 2–3 independent experiments. NS, not significant; * P<.05; *** P<.001;**** P<. 0001.

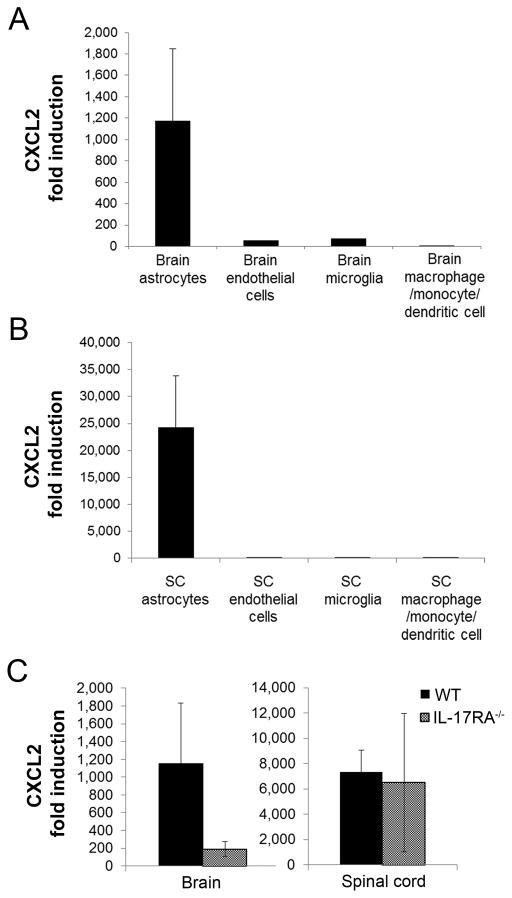

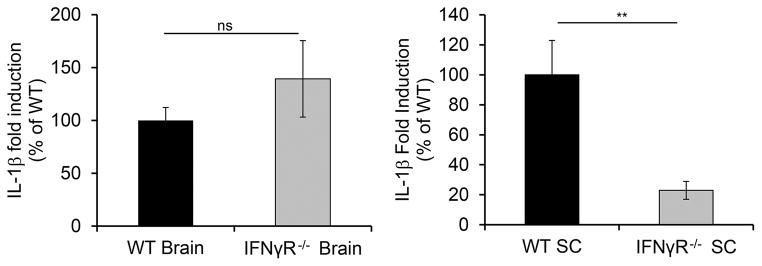

We investigated the source of CXCL2 during EAE by sorting different subsets from CNS mononuclear cells at peak disease and analyzing CXCL2 expression by quantitative PCR. Astrocytes were the predominant producers in both the brain and spinal cord and, as observed for whole tissue, CXCL2 induction was much greater in spinal cord compared to brain astrocytes (Fig. 4A,B). As our data predicted, CXCL2 induction was reduced in astrocytes from brains but not spinal cords of IL-17RA−/− compared to WT mice (Fig. 4C). The observation that IFN-γ promotes CXCL2 induction by astrocytes was surprising as IFN-γ is more commonly known for inducing chemokines that attract monocytes (16, 17). Therefore, we hypothesized that IFN-γ may induce CXCL2 indirectly via induction of other inflammatory mediators. Because IFN-γ signaling can promote expression of IL-1β, a known inducer of ELR+ chemokines (18), we analyzed IL-1β expression in brain and spinal cords of WT and IFN-γ R−/− mice. While no differences were observed in the brain, IL-1β induction was significantly decreased (~5-fold, P<.01) in spinal cords of IFN-γR−/− compared to WT mice (Fig. 5). Thus, IFN-γ may induce CXCL2 in the spinal cord but not the brain via its spinal cord-specific induction of IL-1β.

FIGURE 4. Astrocyte induction of CXCL2 is dependent on IL-17 signaling in the brain but not spinal cord.

(A-B)Fold induction of CXCL2 compared to cells from naïve mice was determined by quantitative PCR for astrocytes (CD45−GFAP+), endothelial cells (CD45−CD31+), microglia (CD45midCD11b+), and CD45hiCD11b+cells sorted from the brains (A) and spinal cords (SC, B) of WT mice with EAE ≥ 3. Data are compiled from 2 independent experiments with a total of 4 mice per group. (C) Fold induction of CXCL2 determined by quantitative PCR for astrocytes sorted from the brains and spinal cords of WT and IL-17RA−/− mice with EAE ≥ grade 3 compared to astrocytes sorted from healthy control brains. Data are compiled from 2 independent experiments, with 4 WT and 4 IL-17RA−/− brains and pooled samples from a total of 6 WT and 5 IL-17RA−/− spinal cords

FIGURE 5. IFN-γ signaling promotes IL-1β in spinal cord but not brain tissue.

Expression levels of IL-1β were determined by quantitative PCR for brain (left) and spinal cord (right) tissue harvested from WT (n=7) and IFN-γR−/−(n=8) mice with EAE ≥ grade 3. Fold induction of IL-1β is shown for tissues from IFN-γR−/− mice compared to healthy controls with expression of IL-1β in WT EAE mice assigned a value of 100%. Data are compiled from 2 independent experiments. NS, not significant; ** P<.01.

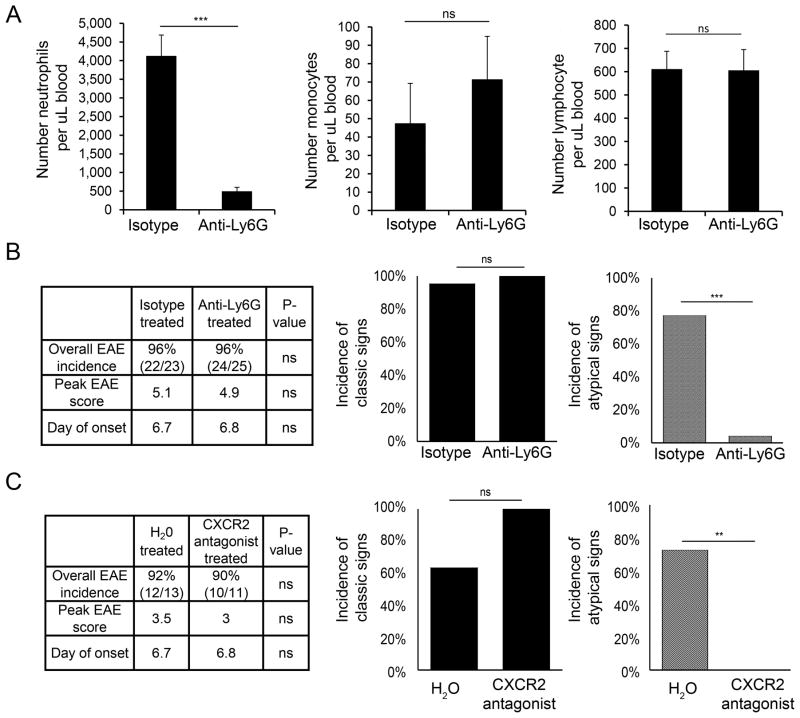

Neutrophil depletion and disruption of CXCR2 signaling prevent parenchymal tissue injury in the brain but not spinal cord

Our finding that neutrophil recruitment to a particular CNS region (brain or spinal cord) correlated with clinical signs reflecting inflammation in that region suggested that neutrophils may play a critical role in promoting CNS tissue injury during EAE. To test this hypothesis, we administered the neutrophil-specific anti-Ly6G antibody beginning on the day of T cell transfer. Neutrophils were reduced by 90% in the blood without affecting either monocytes or lymphocyte number (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, neutrophil depletion did not affect the overall incidence, onset, or severity of EAE. However, neutrophil depletion had a striking effect on the clinical manifestation of EAE (Fig. 6B). The incidence of atypical signs was dramatically reduced in neutrophil-depleted compared to control mice. In contrast, neither the incidence (Fig. 6B) nor severity (data not shown) of classic EAE signs was affected by treatment with neutrophil-depleting antibody. These data suggest that neutrophils are required for brain, but not spinal cord inflammation during EAE.

FIGURE 6. Atypical EAE is dependent on neutrophil infiltration.

(A) The absolute number of neutrophils (left), monocytes (middle), and lymphocytes (right) as assessed by CBC with differential is shown for isotype control antibody-treated (n=8) and anti-Ly6G-treated (n=8) mice. (B) Clinical data (left) from WT mice treated with anti-Ly6G or isotype control are shown. Peak EAE score and clinical onset were calculated from mice that succumbed to EAE. Incidence of classic EAE signs with or without accompanying atypical EAE signs (middle) and incidence of atypical EAE signs with or without accompanying classic signs (right) are shown as a percentage of sick mice. Data are compiled from 5 independent experiments (isotype control-treated, n=22; anti-Ly6G-treated, n=24). (C) Clinical data (left) from WT mice treated with CXCR2 antagonist or vehicle control (H20) are shown. Peak EAE score and clinical onset were calculated from mice that succumbed to EAE. Incidence of classic EAE signs (middle) and atypical EAE signs (right) were determined as in (B). Data are compiled from 2 independent experiments (control, n=12; CXCR2 antagonist-treated, n=10). NS, not significant; ** P<.01; *** P<.001.

As our data implicate CXCL2 as a major determinant of neutrophil recruitment to both the brain and spinal cord, we investigated whether blocking ELR+ chemokine signaling in vivo would recapitulate the therapeutic effect of neutrophil depletion by ameliorating atypical EAE. A small molecule antagonist of CXCR2, the main receptor for ELR+ chemokines on neutrophils, was administered daily beginning on the day of T cell transfer. The onset, peak severity, and incidence of classic EAE signs were similar between CXCR2 antagonist-treated and control mice (Fig. 6C). Importantly, the incidence of atypical signs was reduced from 73% in mice treated with vehicle control to 0% in antagonist-treated mice (Fig. 6C). Thus, antagonizing CXCR2 signaling in vivo during EAE is therapeutically equivalent to neutrophil depletion in preventing clinical signs of brain inflammation.

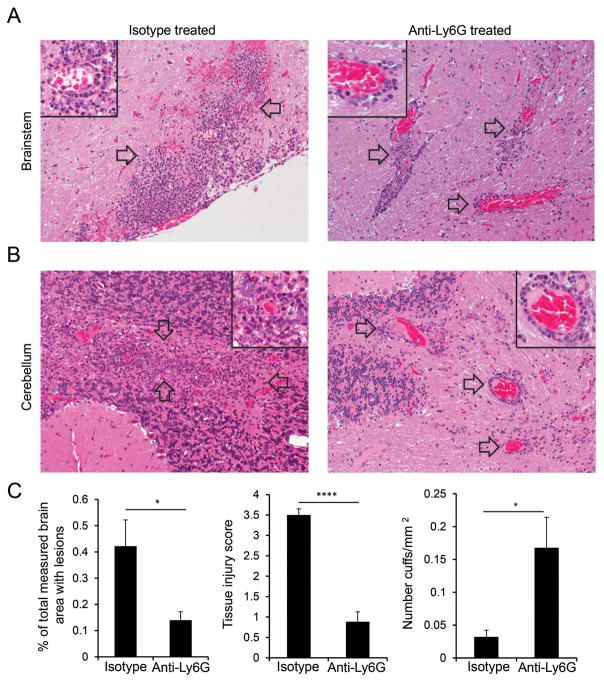

To confirm that the dramatic reduction in atypical clinical signs that was observed upon neutrophil depletion reflected decreased tissue damage in the brain, we performed histopathological analyses of brain sections from neutrophil-depleted and control mice. Loss of blood vessel wall integrity and extensive infiltration of parenchymal brain tissue by inflammatory cells as well as occasional hemorrhage was observed in mice treated with isotype control antibody (Fig. 7A,B, left). In contrast, inflammatory cells consisting primarily of mononuclear cells were predominantly localized around blood vessels and significant migration into the surrounding parenchyma was not seen in the brains of neutrophil-depleted mice (Fig. 7A,B right). This distribution of inflammatory cells resulted in a pattern of pronounced perivascular cuffing that was not commonly seen in comparable sections from control mice. These changes caused a significant reduction in the percent area of brain sections populated by inflammatory foci in anti-Ly6G-treated compared to control mice (Fig. 7C, left). We also quantified the extent of tissue damage observed in tissue sections by assigning a tissue injury score based on the extent of necrotic and apoptotic cell death associated with inflammatory lesions. Importantly, a significant reduction in tissue injury was observed in the brains of neutrophil-depleted versus control mice (Fig. 7C, middle), accompanied by an increase in the number of perivascular cuffs/section (Fig 7C, right). Despite the impaired parenchymal migration of inflammatory cells in the brains of neutrophil-depleted mice, a diffuse pattern of gliosis was occasionally observed in the parenchyma of anti-Ly6G treated-mice, which may reflect the activity of soluble inflammatory mediators. Overall, these findings in the brain are consistent with the ability of neutrophils to affect the integrity of the blood/brain barrier and enhance migration of inflammatory cells beyond the perivascular space to promote parenchymal tissue injury.

FIGURE 7. Tissue damage in the brain requires neutrophil infiltration.

(A-B) Histopathology is shown for representative sections from brainstem (A) and cerebellum (B) from WT mice with EAE ≥ grade 3 that were treated with either isotype control (left) or anti-Ly6G antibody (right). Images (20X) are representative of 12 isotype control-treated and 13 anti-Ly6G-treated mice from 3 independent experiments. Focally extensive highly cellular inflammatory lesions (arrows) predominate in white matter of control animals (left); insets (60X) reveal dense accumulation of neutrophils admixed with fewer mononuclear cells as well as necrotic and apoptotic cell debris in lesions. In contrast, lesions within similar white matter regions of anti-Ly6G-treated mice (right) lack the obvious extended parenchymal involvement seen in control mice. These lesions have a more localized perivascular signature (arrows) comprised predominantly of mononuclear cells and are associated with a much diminished necrotic change (inset). (C) Analyses of brain sections from 12 isotype control-treated and 13 anti-ly6G-treated mice with EAE ≥ 3 are shown quantifying the total brain sectional area affected with lesions (left), the severity of tissue injury (middle), and the prevalence of perivascular cuffing (right). Data are compiled from 3 independent experiments. * P<.05; **** P<.0001

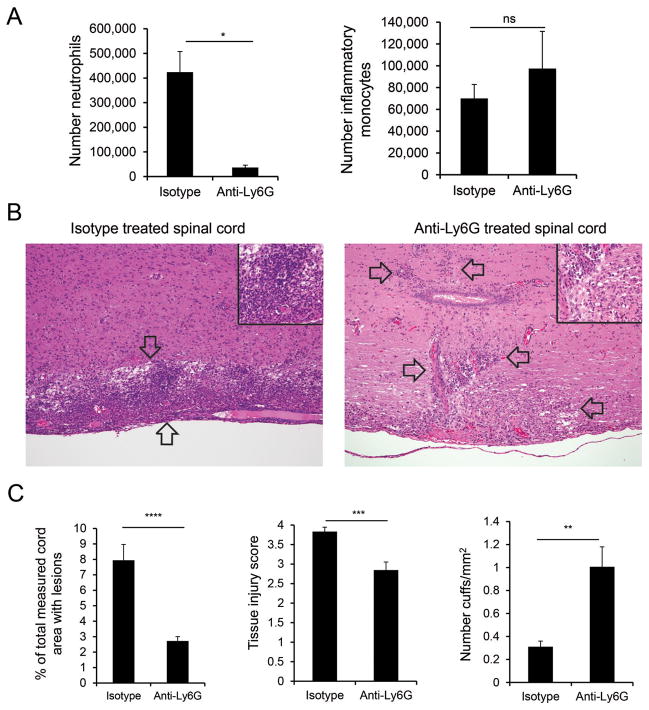

Our unexpected finding that anti-Ly6G treatment did not ameliorate classic EAE signs despite a >90% reduction in neutrophil number in the spinal cord (Fig. 8A) suggested that the spinal cord may differ from the brain in its dependence on neutrophil infiltration for tissue injury. Indeed we found that, although spinal cords in control mice exhibited extensive parenchymal involvement (Fig. 8B, left) and spinal cords from anti-Ly6G treated-mice demonstrated increased perivascular cuffing (Fig. 8B, right) there was only a modest reduction in the extent of tissue injury in treated compared to control animals. Strikingly, the extent of necrotic and apoptotic cell death associated with inflammatory lesions in the spinal cord of anti-Ly6G-treated mice was much greater than that seen in brain tissue analyzed from the same mice. Thus, despite the decrease in the area populated by inflammatory cells in the spinal cords of neutrophil-depleted mice (Fig. 8C, left), there was only a 25% decrease in tissue injury (Fig. 8C, middle) compared to the 75% decrease in tissue injury seen in the brain (Fig. 7C). These results, together with the ability of neutrophil depletion to affect atypical but not classic EAE signs, indicate that preventing neutrophil infiltration during CNS autoimmunity has a much greater impact on tissue injury in the brain compared to the spinal cord.

FIGURE 8. Tissue damage in the spinal cord is less dependent on neutrophils than the brain.

(A) The absolute number of neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+Ly6Cint, left) and inflammatory monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6Chi, middle) assessed by flow cytometry are shown for spinal cords of isotype control-treated (n=4) and anti-Ly6G-treated (n=4) mice. (B) Histopathology is shown for representative spinal cord sections from WT mice treated with isotype control (left) or anti-Ly6G antibody (right). Images (10X) are representative of 12 isotype control-treated and 13 anti-Ly6G-treated mice from 3 independent experiments. Focally extensive highly cellular inflammatory lesions (between arrows) predominate in control animals (left); inset (60X) reveals dense accumulation of neutrophils admixed with fewer mononuclear cells as well as necrotic and apoptotic cell debris in lesions. In spinal cords of anti-Ly6G-treated mice (right), mononuclear cells surround vessels or are present as focal accumulations (arrows); lesions are associated with some necrotic and apoptotic cell debris and are comprised predominantly of mononuclear cells (inset; 60X). (C) Analyses of spinal cord (SC) sections from 12 isotype control-treated and 13 anti-ly6G-treated mice with EAE ≥ 3 are shown quantifying the total spinal cord sectional area affected with lesions (left), the severity of tissue injury (middle), and the prevalence of perivascular cuffing (right). Data are compiled from 3 independent experiments. ** P<.01; *** P<.001; **** P<.0001.

DISCUSSION

We show here that the mechanism by which IL-17 and IFN-γ influence lesion formation in the brain arises from their ability to regulate, in an opposing fashion, CXCL2 induction and neutrophil recruitment to this microenvironment. Regulation of CXCL2 expression by IFN-γ is particularly striking as IFN-γ inhibits CXCL2 production in the brain but promotes it s induction in the spinal cord. Interestingly, we found that astrocytes are the predominant source of CXCL2 in both microenvironments, yet we found no differences by flow cytometry in IFN-γ R expression by brain versus spinal cord astrocytes(data not shown). Our finding that IFN-γ signaling also induced IL-1β in the spinal cord but not the brain suggests that IFN-γ could induce CXCL2 indirectly in the spinal cord via induction of IL-1β, and further highlights the profound differences in response to inflammatory stimuli within the brain versus spinal cord. Our results also establish a critical role for neutrophil recruitment to the brain by demonstrating that neutrophils are required to promote the disseminated leukocyte infiltration that leads to severe tissue damage in the brain. In the absence of neutrophils, inflammatory cells were largely retained in perivascular spaces, resulting in only mild gliosis in the surrounding brain tissue. This is consistent with other reports that neutrophils enhance blood-brain-barrier permeability (19) and promote invasion of immune cells into tissue parenchyma (8, 20). Our finding that neutrophils play a less obligatory role in promoting tissue damage in the spinal cord was therefore very surprising and has important therapeutic implications. Some tissue damage in the spinal cord was ameliorated by neutrophil depletion, but the protection afforded by this treatment was much less than that observed in the brain. It is possible that the small number of neutrophils that remain following treatment with anti-Ly6G is sufficient to induce injury in the spinal cord. However, while atypical EAE signs were abolished by treatment with a CXCR2 antagonist, 100% of these mice still developed classic EAE with comparable severity as that seen in control mice. This observation supports the notion that spinal cord tissue may be more sensitive than brain tissue to injury mediated by inflammatory cells other than neutrophils that are recruited via a CXCR2-independent mechanism.

The mechanisms that regulate spinal cord inflammation in EAE have been controversial. IL-17 signaling was shown to be important in some (21–24), but not all (9, 10, 25) models of classic EAE. Likewise, IFN-γ was shown to promote spinal cord inflammation in some (2, 4, 26), but not all (9, 20) classic EAE models. While these disparate results may reflect differences in EAE models, our data suggest that distinct inflammatory cell types may play more redundant roles in inducing spinal cord inflammation compared to the brain.

Previous studies in patients with MS, the majority of whom have lesions in the brain parenchyma, support a role for an IL-17 -induced ELR+ chemokine pathway in the pathogenesis of the disease. IL-17 transcript-expressing mononuclear cells are enriched in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)of patients with MS compared to healthy controls, and are enriched in the CSF of patients with MS during exacerbation compared to remission (27). In addition, protein levels of CXCL8, the human ortholog for CXCL1 and CXCL2, are increased in the CSF of patients with MS (28). Importantly, early phase IIa clinical trials indicated that treatment with secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against IL-17A, resulted in a reduction in inflammatory lesions in the brain and a trend towards reduced clinical relapses in MS patients compared to placebo-treated controls (29). Nevertheless, a role for neutrophils in MS has been controversial because they are not often found in CNS tissue obtained either post-mortem or by biopsy from patients with MS. Notably, our studies suggest that neutrophils could be most relevant during the early stages of MS by facilitating the initial leukocyte trafficking from the perivascular space into the brain parenchyma, while tissue sections from MS patients are typically analyzed long after disease onset. The observation that the proportion of neutrophils in the CSF of pediatric MS patients decreases with increasing disease duration while the proportion of lymphocytes and monocytes increases (30)supports the notion that neutrophils may be most important during the initial stages of disease. A role for neutrophils in chronic disease, however, is also suggested by the observation that neutrophils in the blood of MS patients exhibit a primed phenotype compared to healthy controls and that neutrophil numbers increase during disease relapse (31). Additionally, treatment with rhG-CSF, which supports neutrophil activation, worsens the clinical status in patients with MS (32), and neutrophil depletion in a relapsing-remitting EAE model inhibited relapses (19). Together these observations suggest that neutrophils may play a more important role in the pathogenesis of MS than previously appreciated. In conclusion, our results suggest that therapeutic strategies that decrease neutrophil recruitment may be most beneficial in patients with MS when lesions dominate in the brain compared to spinal cord. Thus, the predominant site of lesion activity in a patient may be an important parameter in designing effective therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Johnson and Katja Dove for critical reading of the manuscript, and Jessica Swarts and Neal Mausolf for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from NIAID to J.M. Goverman (R37 AI107494-01) and from NINDS to S. B. Simmons (1F30NS071712-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used in this article

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- IL-17RA

IL-17 receptor A

- IFN-γR

IFN-γ receptor α

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- SC

spinal cord

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Muller DM, Pender MP, Greer JM. A neuropathological analysis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with predominant brain stem and cerebellar involvement and differences between active and passive induction. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000;100:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s004019900163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wensky AK, Furtado GC, Marcondes MC, Chen S, Manfra D, Lira SA, Zagzag D, Lafaille JJ. IFN-gamma determines distinct clinical outcomes in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2005;174:1416–1423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsunoda I, Kuang LQ, Theil DJ, Fujinami RS. Antibody association with a novel model for primary progressive multiple sclerosis: induction of relapsing-remitting and progressive forms of EAE in H2s mouse strains. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:402–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lees JR, Golumbek PT, Sim J, Dorsey D, Russell JH. Regional CNS responses to IFN-gamma determine lesion localization patterns during EAE pathogenesis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2633–2642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greer JM, Sobel RA, Sette A, Southwood S, Lees MB, Kuchroo VK. Immunogenic and encephalitogenic epitope clusters of myelin proteolipid protein. J Immunol. 1996;156:371–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storch MK, Stefferl A, Brehm U, Weissert R, Wallstrom E, Kerschensteiner M, Olsson T, Linington C, Lassmann H. Autoimmunity to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in rats mimics the spectrum of multiple sclerosis pathology. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:681–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollinger B, Krishnamoorthy G, Berer K, Lassmann H, Bosl MR, Dunn R, Domingues HS, Holz A, Kurschus FC, Wekerle H. Spontaneous relapsing-remitting EAE in the SJL/J mouse: MOG-reactive transgenic T cells recruit endogenous MOG-specific B cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1303–1316. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abromson-Leeman S, Bronson R, Luo Y, Berman M, Leeman R, Leeman J, Dorf M. T-cell properties determine disease site, clinical presentation, and cellular pathology of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1519–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63410-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke MA, Chensue SW, Segal BM. EAE mediated by a non-IFN-gamma/non-IL-17 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2340–2348. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stromnes IM, Cerretti LM, Liggitt D, Harris RA, Goverman JM. Differential regulation of central nervous system autoimmunity by T(H)1 and T(H)17 cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nm1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothhammer V, Heink S, Petermann F, Srivastava R, Claussen MC, Hemmer B, Korn T. Th17 lymphocytes traffic to the central nervous system independently of alpha4 integrin expression during EAE. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2465–2476. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdul-Majid KB, Jirholt J, Stadelmann C, Stefferl A, Kjellen P, Wallstrom E, Holmdahl R, Lassmann H, Olsson T, Harris RA. Screening of several H-2 congenic mouse strains identified H-2(q) mice as highly susceptible to MOG-induced EAE with minimal adjuvant requirement. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;111:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brabb T, von Dassow P, Ordonez N, Schnabel B, Duke B, Goverman J. In situ tolerance within the central nervous system as a mechanism for preventing autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2000;192:871–880. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.6.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SY, Goverman JM. The influence of T cell Ig mucin-3 signaling on central nervous system autoimmune disease is determined by the effector function of the pathogenic T cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:4991–4999. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadik CD, Kim ND, Luster AD. Neutrophils cascading their way to inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter SL, Muller M, Manders PM, Campbell IL. Induction of the genes for Cxcl9 and Cxcl10 is dependent on IFN-gamma but shows differential cellular expression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and by astrocytes and microglia in vitro. Glia. 2007;55:1728–1739. doi: 10.1002/glia.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang D, Han Y, Rani MR, Glabinski A, Trebst C, Sorensen T, Tani M, Wang J, Chien P, O'Bryan S, Bielecki B, Zhou ZL, Majumder S, Ransohoff RM. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation of the nervous system: manifold roles and exquisite regulation. Immunol Rev. 2000;177:52–67. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gil MP, Bohn E, O'Guin AK, Ramana CV, Levine B, Stark GR, Virgin HW, Schreiber RD. Biologic consequences of Stat1-independent IFN signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6680–6685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111163898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson T, Kroenke M, Rao P, Lane TE, Segal B. The Th17-ELR+ CXC chemokine pathway is essential for the development of central nervous system autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2008;205:811–823. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran EH, Prince EN, Owens T. IFN-gamma shapes immune invasion of the central nervous system via regulation of chemokines. J Immunol. 2000;164:2759–2768. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofstetter HH, Ibrahim SM, Koczan D, Kruse N, Weishaupt A, Toyka KV, Gold R. Therapeutic efficacy of IL-17 neutralization in murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cell Immunol. 2005;237:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Garcia I, Zhao Y, Ju S, Gu Q, Liu L, Kolls JK, Lu B. IL-17 signaling-independent central nervous system autoimmunity is negatively regulated by TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2009;182:2665–2671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y, Ota N, Peng I, Refino CJ, Danilenko DM, Caplazi P, Ouyang W. IL-17RC is required for IL-17A- and IL-17F-dependent signaling and the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4307–4316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haak S, Croxford AL, Kreymborg K, Heppner FL, Pouly S, Becher B, Waisman A. IL-17A and IL-17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro-inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:61–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI35997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke MA, Segal BM. IL-23 modulated myelin-specific T cells induce EAE via an IFNgamma driven, IL-17 independent pathway. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2011;25:932–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matusevicius D, Kivisakk P, He B, Kostulas N, Ozenci V, Fredrikson S, Link H. Interleukin-17 mRNA expression in blood and CSF mononuclear cells is augmented in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1999;5:101–104. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartosik-Psujek H, Stelmasiak Z. The levels of chemokines CXCL8, CCL2 and CCL5 in multiple sclerosis patients are linked to the activity of the disease. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havrdová E, AB, Goloborodko A, Tisserant A, Jones I, Garren H, Johns D. Late Breaking News 2: Positive proof of concept of AIN457, an antibody against interleukin-17A, in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2012;18:513. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chabas D, Ness J, Belman A, Yeh EA, Kuntz N, Gorman MP, Strober JB, De Kouchkovsky I, McCulloch C, Chitnis T, Rodriguez M, Weinstock-Guttman B, Krupp LB, Waubant E. Younger children with MS have a distinct CSF inflammatory profile at disease onset. Neurology. 2010;74:399–405. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ce5db0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naegele M, Tillack K, Reinhardt S, Schippling S, Martin R, Sospedra M. Neutrophils in multiple sclerosis are characterized by a primed phenotype. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;242:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Openshaw H, Lund BT, Kashyap A, Atkinson R, Sniecinski I, Weiner LP, Forman S. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis with busulfan and cyclophosphamide conditioning: report of toxicity and immunological monitoring. Biol Blood Marrow TR. 2000;6:563–575. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.