Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this investigation was to identify distinctive clinical correlates of psychotic major depression (PMD) as compared with non-psychotic major depression (NPMD) in a large cohort of Korean patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods

We recruited 966 MDD patients of age over 18 years from the Clinical Research Center for Depression of South Korea (CRESCEND) study. Diagnoses of PMD (n=24) and NPMD (n=942) were made with the DSM-IV definitions and confirmed with SCID. Psychometric scales were used to assess overall psychiatric symptoms (BPRS), depression (HAMD), anxiety (HAMA), global severity (CGI-S), suicidal ideation (SSI-Beck), functioning (SOFAS), and quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF). Using independent t-tests and χ2 tests, we compared clinical characteristics of patients with PMD and NPMD. A binary logistic regression model was constructed to identify factors independently associated with increased likelihood of PMD.

Results

PMD subjects were characterized by a higher rate of inpatient enrollment, and higher scores on many items on BPRS (somatic concern, anxiety, emotional withdrawal, guilt feelings, tension, depression, suspiciousness, hallucination, motor retardation, blunted affect and excitement) global severity (CGI-s), and suicidal ideation (SSI-Beck). The explanatory factor model revealed that high levels of tension, excitement, and suicidal ideation were associated with increased likelihood of PMD.

Conclusion

Our findings partly support the view that PMD has its own distinctive clinical manifestation and course, and may be considered a diagnostic entity separate from NPMD.

Keywords: Psychotic major depression, Distinctive correlates, Diagnostic entity

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a major public health issue and is responsible for an economic burden that was estimated to have exceeded 1.5 billion USD for year 2004 in South Korea.1,2 There has been much debate on how to precisely delineate the subtypes of depression that have been identified. Psychotic major depression (PMD) denotes clinical condition of presence of psychotic symptoms in addition to the depressive disorder. Since 15-19% of those diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) have concurrent delusional or hallucinatory symptoms and because 20-25% of cases admitted with depression present with psychotic symptoms,3,4,5 PMD is occasionally considered as a standard clinical condition.

The definition of PMD originated from a Kraepelinian dichotomous view. Since DSM-II stated that psychotic depressive reactions referred to severe depressive episodes in response to one or more identifiable stressor, depressed patients with mood-incongruent delusions were regarded as a subtype of schizophrenia or of schizoaffective disorder. In DSM-III and DSM-III-R, the specifier "with psychotic features" reflected the presence of delusion or hallucination, and thought disorders were regarded as reflecting the severity of a depressive disorder rather than a distinctive feature. The "severity-psychosis" hypothesis stipulates that severe levels of depression result in psychotic symptoms, and this view is generally accepted in contemporary psychiatric nosology or taxonomy. In both ICD-10 and DSM-IV, PMD is currently classified as a subtype of severe depression, or a severe variant of depression.6,7,8 Thus, the presence of delusion or hallucination has been conceptualized as the hallmark of PMD distinguishing it from non-psychotic major depression (NPMD). Furthermore depressive symptoms,9,10 psychomotor disturbances9,11 and guilt9,12,13 have been suggested as accessory features separating PMD and NPMD. On the other hand, several psychiatrists have insisted that PMD is a clinical syndrome distinct from PMD, based on a large body of findings of clinical and translational studies.6,7 Thus, there has been a longstanding debate about whether PMD is merely a subtype of depression distinguished by its severity, or is a distinctive diagnostic entity.

To our knowledge, clinical features of PMD have usually been derived from clinic-based findings rather than cohort-based data. Moreover, relatively little epidemiological and distinctive characteristics of PMD have been reported in Korea. The Clinical Research Center for Depression (CRESCEND) study was the first large, prospective, observational, clinical study of a nationwide sample of Korean patients with depressive disorders, and provided epidemiological data using psychometric scales to measure a number of clinical variables.14 Using data from the CRESCEND study, we aimed to define the epidemiological characteristics of PMD and identify its distinctive clinical correlates as compared with NPMD in a large cohort of Korean patients with MDD. More specifically, the study aimed to answer the following questions:

How many of the patients in the CRESCEND study suffer from PMD?

Which clinical variables are significantly different in a comprehensive comparison of subjects with PMD and NPMD?

Which variables are independently associated with an increased likelihood of PMD in a binary logistic regression model?

METHODS

Study overview

From January 2006 to August 2008, 1183 patients with depressive disorders were enrolled in the CRESCEND study at one of the 18 study centers across South Korea, including 16 university-affiliated hospitals and two general hospitals. The study was conducted over a period of nine years. During phase I, eligible subjects were assessed at baseline, followed by assessments in weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 52. In phase II, subjects were assessed annually over the course of eight years. The data management center, which monitored the collection and quality of data, was situated in the Department of Preventative Medicine of the Catholic University College of Medicine (Seoul, Korea). All sociodemographic and clinical data were collected by trained and certified clinical research coordinators who were supervised by clinical psychiatrists at the regional centers. All patient data were recorded using a preselected clinical report form and entered into the database via the CRESCEND study website (www.smileagain.or.kr).14

Study subjects

In order to closely reflect the real clinical situation, the study had broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria. Psychiatric inpatients and outpatients who were beginning new treatment for first-onset or recurrent depression were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age over seven years, and 2) presence of PMD or NPMD, dysthymic disorder, or depressive disorders not otherwise specified, according to DSM-IV criteria.18 The exclusion criteria were: 1) current or lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, organic psychosis or dementia, according to DSM-IV criteria; 2) presence of a medical or neurological illness severe enough to interfere with study evaluations and interviews; and/or 3) breastfeeding, pregnancy, or intention to become pregnant within nine months of enrolment.

Respective institutional review boards (IRBs) approved the study protocol and consent forms at each of the 18 institutions where the study was performed. All study participants, or their legal guardians, provided written informed consent prior to participation. For participants aged under 16 years, written consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian as well as the participant. Where a patient was very old or physically ill, the nature and purpose of study was explained to him or her, and written informed consent was obtained from that person or their caregiver, as appropriate.14

Definition of psychotic major depression and psychotic features

Diagnoses of depressive disorders were made by attending clinicians using the DSM-IV criteria.15 Diagnoses were confirmed within 2 weeks, using the DSM-IV-based Structured Clinical Interview (SCID).16 Consensus was achieved by including the evaluation of a supervisory psychiatrist and viewing videotapes featuring standard MDD patients with or without psychotic features. Diagnosis limited to PMD or NPMD was used as an inclusion criterion for the analysis described here, whereas it was not used to determine inclusion in the CRESCEND study. Hence, subjects with dysthymic disorder or depressive disorder not otherwise specified were not included in our study. Moreover, subjects younger than 18 years were also excluded to control the effects of the differences of clinical manifestations according to age. Hence, we recruited 966 patients with MDD from the CRESCEND study. Psychotic features corresponded to the diagnostic constructs of DSM-IV. Delusion was defined as "a false, unshakeable idea or belief which is out of keeping with the patient's educational, cultural and social background." Delusion was classified into the subtypes of persecution, guilt, nihilism, somatic and other, and its presence or absence was evaluated. Hallucination was defined as "perception without normal external stimulus correspondence" and its presence or absence was assessed. The presence of hallucination was indicated by score of ≥3 on the BPRS hallucinations subscale.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The sociodemographic data collected on clinical report forms included age, sex, marital status (currently married or not), educational status (below or above high school education level), current occupation (currently employed or not), religious affiliation (religious observance or not), and monthly income (below or above 2000 USD).

Diagnostic evaluation and retrospective reporting of the medical history and/or psychiatric illness and treatment took place at baseline. Clinical data collected in the study included outpatient/inpatient enrollment, history of depressive episodes, age at onset of first depressive episode, family history of depression, and history of suicide attempts. The section concerning concurrent physical disorders had questions on the presence or absence of 33 listed physical disorders, including hypertension, cancer, diabetes, angina, cerebrovascular disease, thyroid disease, osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, Cushing's disease, uremia, gastroduodenal ulcer, inflammatory bowel disease, and others. As treatment status and severity of physical disorders were also recorded, patients with a concurrent medical or neurological illness that was severe enough to interfere with study participation were excluded.

Assessment scale scores

To evaluate clinical, social, and functional outcomes, the following clinician-administered assessment scales were applied: the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),17 the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD),18 the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA),19 the Clinical Global Impression of Severity Scale (CGI-s)20 and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS).21 Moreover, self-administered assessment scales including the Scale for Suicide ideation (SSI-Beck)22 and the WHO quality of life assessment instrument-abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF)23 were also applied. Higher scores on the BPRS, the HAMD, the HAMA, the CGI-s, and the SSI-Beck, and lower scores on the SOFAS and the WHOQOL-BREF all indicate more severe symptomatology or impact. All scales had been formally translated into the Korean language and standardized.24,25 In the BPRS, each item is rated from one (absence of symptoms) to seven (extremely severe). Using all of the individual items on BPRS, clinical manifestations of PMD subjects were compared with those of NPMD subjects. On the HAMA, each item is rated from zero (not present) to four (severe). The CGI-s items rated from one (not ill) to seven (extremely severe). The SOFAS is rated from one to a hundred. Training for all of the raters was performed twice a year, with a formal consensus meeting for applying the rater-administered assessment instruments.

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic factors, clinical characteristics, and assessment scale scores were compared between the PMD and NPMD groups using the independent t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. To present the magnitude of group differences, Cohen's d statistics (0.2=small, 0.5=medium, and 0.8=large), or odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI), were also computed. A binary logistic regression model was constructed to identify factors associated with an increased likelihood of PMD. In the model, the PMD group was defined as the dependent variable, while the NPMD group was defined as the reference. Initial covariates selected for binary logistic model were variables that differed significantly between the PMD and NPMD groups. Standard methods such as goodness of fit that control for interaction and colinearity were used to select and validate the final model. Logistic regression was based on a forward selection method to avoid colinearity. Significance was set at p<0.01 (two-tailed) for all tests, to reduce familywise error due to multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Overall subject characteristics

Table 1 and 2 summarize sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 966 patients. The mean age was 48.3 (SD=15.2) years, and most of patients were female (75.7%), married (62.2%), employed (68.6%), religiously affiliated (62.1%), with a monthly income <2000 USD (52.1%), and enrolled as outpatients (76.9%). The mean assessment score was 21.6 (SD=8.0) on the BPRS, 20.2 (SD=6.0) on the HAMD, 19.3 (SD=8.6) on the HAMA, 11.0 (SD=8.7) on the SSI-Beck, 4.7 (SD=1.0) on the CGI-S, 57.3 (SD=11.3) on the SOFAS, and 63.7 (SD=10.4) on the WHOQOL-BREF.

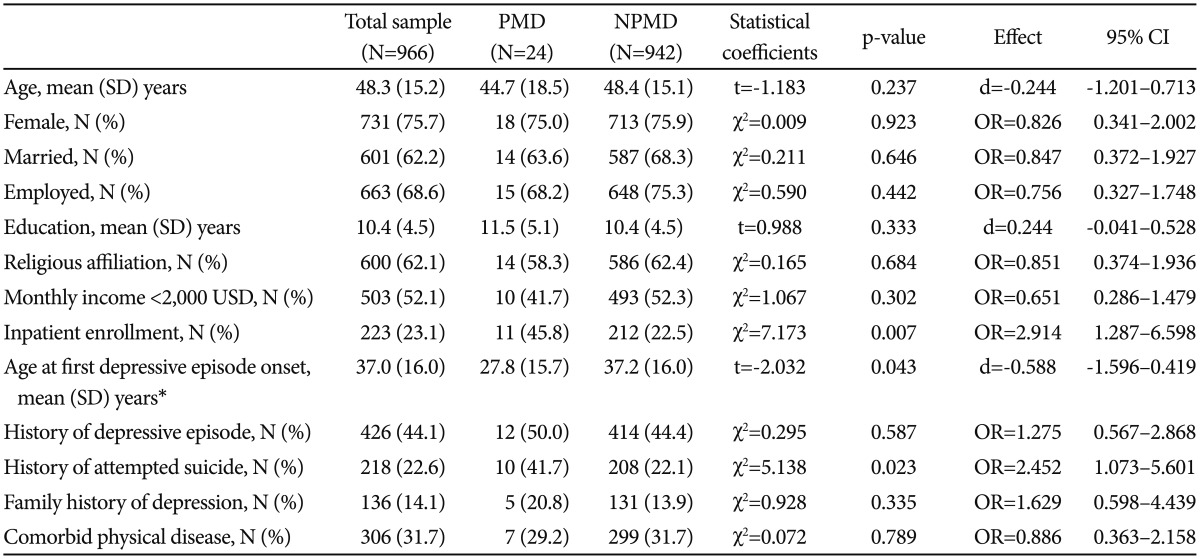

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of subjects

*N=430. CI: confidence interval, NPMD: non-psychotic major depression, PMD: psychotic major depression, SD: standard deviation, USD: United States dollars

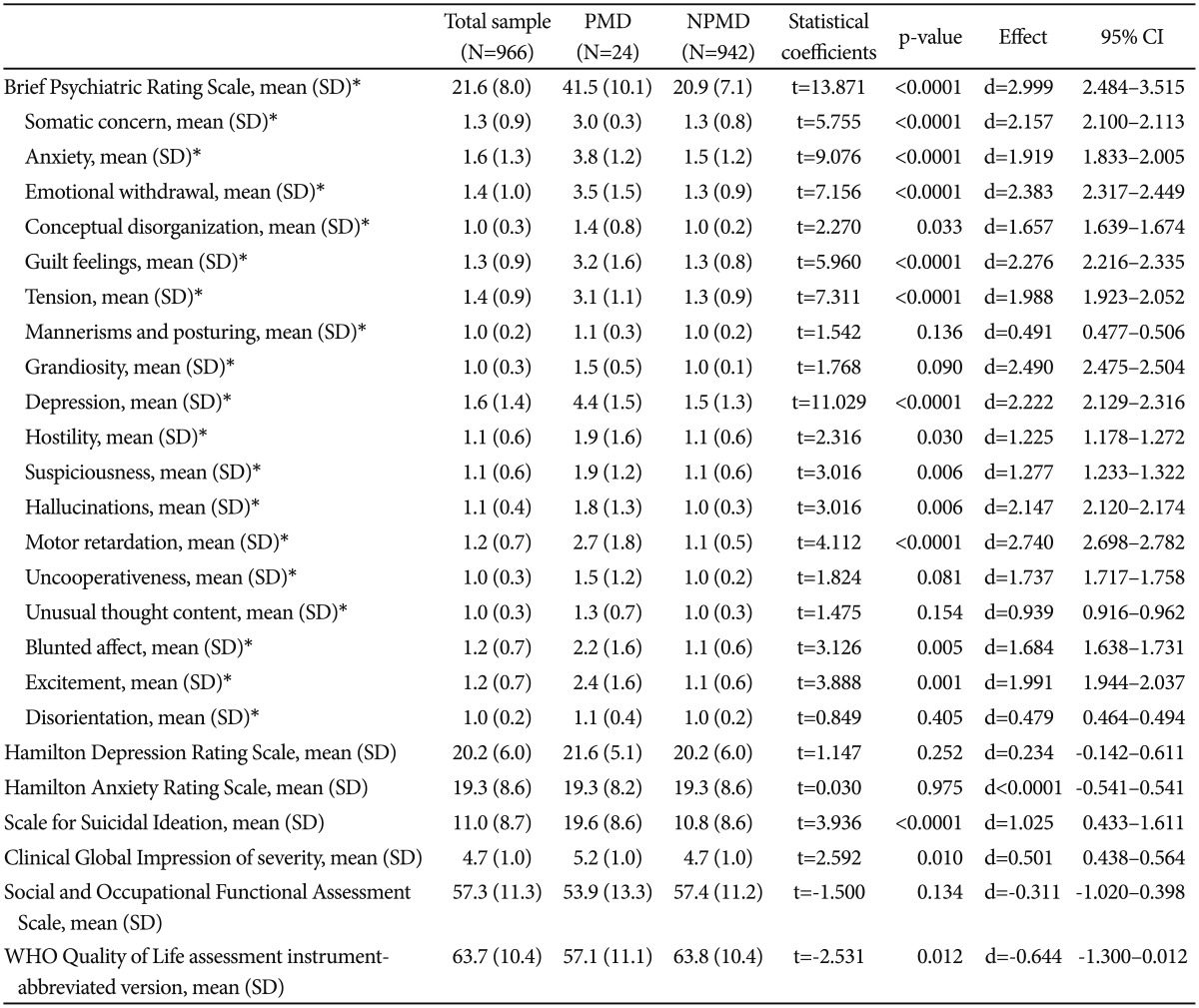

Table 2.

Assessment scale scores of subjects

*N=750. CI: confidence interval, NPMD: non-psychotic major depression, PMD: psychotic major depression, SD: standard deviation

Prevalence of PMD and psychotic features

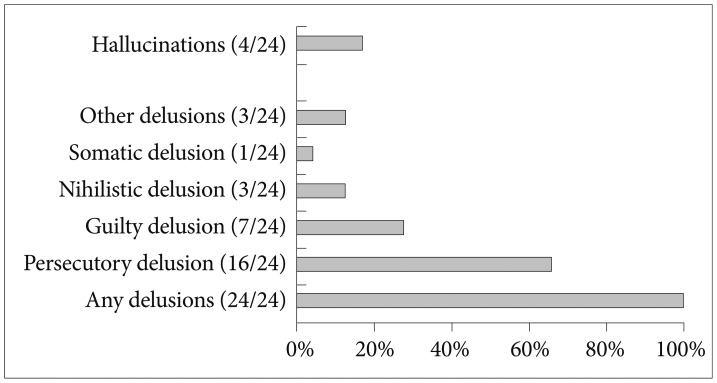

Of the 966 subjects with MDD, 2.5% (n=24) were classified as having PMD. As depicted in Figure 1, all of the subjects with PMD suffered from some type of delusion. Persecutory delusion (n=16; 66.7%) was the most common type reported. Delusions of guilt (n=7; 29.2%) and nihilism (n=3; 12.5%) and somatic delusions (n=1; 4.1%) were also evident. Moreover, 16.7% (n=4) of those with PMD reported hallucinatory experiences.

Figure 1.

Psychotic features of the subjects with psychotic major depression (N=24).

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between the subjects with PMD and NPMD

Sociodemographic characteristics of the PMD and NPMD subjects are compared in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to age (p=0.237, d=-0.244), female gender (p=0.923; OR=0.826), marital status (p=0.646, OR=0.847), current employment (p=0.442; OR=0.756), years of education (p=0.333; d=0.244), religious affiliation (p=0.684; OR=0.851), or monthly income (p=0.302; OR=0.651). Clinical characteristics of the PMD and NPMD subjects were also compared (Table 1). Those with PMD had a higher rate of inpatient enrollment (p=0.007; OR=2.914), and tended to have higher incidence of previous suicidal attempts (p=0.023; OR=2.452). There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to age at onset of first depressive episode (p=0.043; d=-0.588), history of depressive episode (p=0.587; OR=1.275), family history of depression (p=0.335; OR=1.629) or co-occurring physical disease (p=0.789; OR=0. 886).

Comparison of the assessment scale scores of the subjects with PMD and NPMD

Assessment scale scores of PMD and NPMD subjects are compared in Table 2. PMD subjects had a significantly higher total score on the BPRS scale (p<0.0001; d=2.999), including greater scores on specific items of somatic concern (p<0.0001; d=2.157), anxiety (p<0.0001; d=1.919), emotional withdrawal (p<0.0001; d=2.383), guilt feelings (p<0.0001; d=2.276), tension (p<0.0001; d=1.988), depression (p<0.0001; d=2.222), suspiciousness (p=0.006; d=1.277), hallucinations (p=0.006; d=2.147), motor retardation (p<0.0001; d=2.740), blunted affect (p=0.005; d=1.684), and excitement (p=0.001; d=1.991). However, there were no significant differences between the groups with respect to several specific items including conceptual disorganization (p=0.033; d=1.657), mannerisms and posturing (p=0.136; d=0.491), grandiosity (p=0.090; d=2.490), hostility (p=0.030; d=1.225), uncooperativeness (p=0.081; d=1.737), unusual thought content (p=0.154; d=0.939), and disorientation (p=0.405; d=0.479).

PMD subjects also had higher scores on the SSI-Beck (p<0.0001; d=1.025) and CGI-s (p=0.010; d=0.530), and their score on WHO-BREF (p=0.012; d=0.635) tended to be higher.

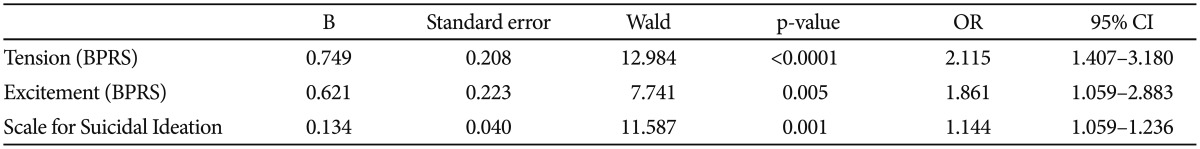

Factors associated with increased likelihood of PMD

The results of binary logistic regression modeling for clinical correlates of PMD are presented in Table 3. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (χ2=7.663, df=8, and p=0.467) confirmed the acceptability of this logistic model. The final model accounted for 43.0% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variability of PMD and demonstrated that tension (BPRS; p<0.0001; OR=2.115; 95%CI=1.407-3.180), excitement (BPRS; p=0.005; OR=1.861; 95%CI=1.202-2.883), and SSI-Beck score (p=0.005; OR=1.144; 95%CI=1.059-1.236) were independently associated with increased likelihood of PMD.

Table 3.

Factors associated with increased likelihood of psychotic major depression

BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Early investigations of PMD tended to focus on patients with delusional depression rather than hallucinatory depression.27 Moreover, many studies showed that PMD patients experienced higher rates of delusion than hallucination. In accord with these findings, delusions were present in all the PMD subjects, whereas hallucinations were only present in a smaller subset (16.7%) (Figure 1). Musalek and colleague28 suggested that persecutory delusional beliefs peaked between years 20-50 and that hypochondriacal themes peaked between years 20-30 as well as at 60 years. Hence, in our study, the high rate (66.7%) of persecutory delusion and low rate (4.1%) of somatic delusions in subjects with PMD may be explained by their relatively young age (44.7 years). Since frequencies of hallucinations in Asians have been poorly investigated and reported with inconsistent findings,29,30 low rates of hallucinations in our study cannot easily be explained. Hence, further studies are needed.

The prevalence of 2.5% for PMD in our study was low in comparison to previous findings that 15% to 19% of patients diagnosed with MDD had psychotic features.3,4 There is no straightforward explanation for this discrepancy, but there are several potential explanations. First, the structured clinical interviews administered to our patients by clinicians, rather than the assessment methods employed in the previous epidemiological surveys, may have contributed to the low rate of PMD diagnosis. Second, psychotic symptoms of low intensity accompanying MDD may have been sometimes under-detected. Psychotic symptoms in depressive disorders are not always overt and even family members find it hard to recognize psychotic symptoms in some depressed patients.31 Third, the low rate of inpatient enrollment (23.1%) in our study may have affected the nature of recruited subjects. About 25% of consecutively admitted depressed patients had psychotic features,5 whereas only 5.3% of the MDD outpatients had delusions or hallucinations.32 Fourth, an influence of racial or ethnic factors on the prevalence of PMD cannot be excluded. In a study from the US, Asian subjects were found to have the lowest prevalence rates of psychotic symptoms compared to Hispanic, African American, and Caucasian subjects.33 Fifth, from the perspective of cultural psychiatry, Koreans with MDD usually present with somatic complaints rather than mental symptoms. Thus, mental symptoms such as psychotic features have often been under-detected in psychometric evaluations.34 Moreover, there is also speculation that the rapid acculturation process in Korea has resulted in changes in MDD symptomatology and an increase in the suicidal completion rate. And, the active efforts for early detection of MDD have contributed to an increase in its prevalence rate. Thus, these changes in the current clinical situation in Korea may be related to the low prevalence of PMD in our study.35 In summary, the relative low rate of PMD in our study could be a result of assessment errors, culture specific clinical presentations, or a combination of these factors.

Several socioeconomic factors including marital status, current employment, and monthly income did not differ between PMD and NPMD subjects in our study. No consistent differences with respect to age at baseline, educational attainment, and economic status have been found between patients with PMD and NPMD.32 We found that PMD subjects had a higher rate of inpatient enrollment than those with NPMD. As mentioned above, inpatients diagnosed with MDD tended to have higher rates of psychotic features than those with NPMD.5,32 It is possible that PMD patients are less likely to seek treatment in outpatient settings.36 PMD subjects also tended to be more likely to have a history of suicidal attempt (41.7% vs. 22.1%), although the difference was not significant. Previous studies have found that PMD patients were 2 to 5 times more likely to have attempted suicide than those with NPMD.33,37 In a study of 183 PMD patients, Schaffer et al.38 found that 21% of these patients had attempted suicide and that the lifetime risk of suicide attempts was negatively associated with advancing age. Thus, it can be said that higher rates of suicide attempts is consistent with findings from previous studies. However, several clinical factors including age at onset of first depressive episode, history of depressive episodes, family history of depression and concomitant physical illnesses did not differ between PMD and NPMD subjects in our study. Some investigations have found that presence of psychotic features was negatively associated with age at onset for patients with affective disorders.39,40 Since age at onset is usually regarded as a useful factor for dissecting the phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of MDD,40 further investigations are needed. In earlier studies, patients with PMD tended to have an increased likelihood of recurrence of depression and an increased risk of family prevalence of unipolar major depression42,43 and bipolar affective disorder.42 The differences between those findings and that of this study may be explained by differences in clinical characteristics of PMD subjects studied.

In addition, PMD subjects scored higher on many of the individual items of the BPRS compared to NPMD subjects. Not only positive symptoms (suspiciousness and hallucinations) but also negative symptoms (emotional withdrawal and blunted affect), guilt feelings, tension and somatic concern were more severe in PMD subjects than in those with NPMD. It has been suggested that psychotic features are sufficient but not necessary for identifying PMD.44 In an epidemiological survey, more than 10% of subjects who had feelings of worthlessness or guilt and suicidal ideation had delusions; that survey also indicated that 9.7% of patients who presented feelings of worthlessness or guilt had hallucinations and that 4.5% had combinations of hallucination and delusions.3 Based on these findings, feelings of worthlessness or guilt have been suggested as good indicators for the presence of psychotic features during depressive episodes. Also, Parker and colleagues13 have suggested that PMD patients are distinguishable from those with NPMD by psychomotor disturbance, depressive content, diurnal variation, and constipation. Furthermore, a number of psychiatric symptoms other than depressive symptoms (including anxiety, paranoia and hypochondriasis) were more severe in PMD patients than in those with NPMD.45

However, the empirical evidence, by which elevated levels of anxiety, paranoia and hypochondria indicate a diagnosis of PMD, is less robust and less consistent than the evidence for elevated levels of unusual thought content, psychomotor disturbance, and guilt feelings.45

We found that total scores on the HAMD did not differ between the two groups, in spite of significantly elevated scores on the items of depression and guilt feelings in the BPRS in PMD subjects. We also noted that the score on the CGI-s were higher (p=0.010; d=0.501) for PMD subjects than for NPMD subjects. Indeed, the clinical manifestations were typically more severe with higher scores on total depression in the PMD patients than in those with NPMD.5 However, our findings were in accord with the previous conclusion that elevated depression scores of PMD patients reflect specific, rather than global, symptoms.31 Hence, our findings partly support the idea that severity of depression alone does not entirely explain the occurrence of psychotic symptoms. Patients with mild to moderate depression usually have psychotic features,3 whereas many patients with severe depression do not.12 Østergaard and colleagues8 also showed that the severity of depression was only weakly correlated with severity of psychotic symptoms in 357 PMD patients. Our findings also provide some support for the view that the occurrence of psychotic features in patients with MDD does not fit the severity-psychosis hypothesis. Our PMD subjects had a higher score on the SSI-Beck than those with NPMD, and a previous study also showed that PMD patients had higher levels of suicidal ideation and were more likely to have attempted suicide in the past.44 Although increased mortality of PMD patients was not due to increased suicide rates in a study by Vythilingam and colleagues,33 patients diagnosed with PMD generally are at high risks of suicide attempts.46

We showed that PMD subjects tended to score higher on the WHOQOL-BREF than NPMD patients, although the difference was not significant. The difference in the scores on the SOFAS between the two groups was also not significant. Goldberg and Harrow47 indicated that social impairment in PMD patients contributed to poorer quality of life. Some studies have indicated that PMD patients have more severe functional impairment with respect to some but not other parameters during follow-up.32

Finally, the binary logistic regression model showed that high levels of tension (BPRS), excitement (BPRS), and suicidal ideation (SSI-Beck) were associated with an increased likelihood of PMD. Excitement has been indicated as correlates of risk for mania or current manic features within clinical samples.48 Hence, this findings partly support the suggestion by Østergaard et al.,7 that the concept of PMD can be modified as a "meta-syndrome" across unipolar and bipolar disorders. Somatic anxiety corresponding to tension has also been seen as a distinctive aspect of MDD symptomatology.49 Another finding of the CRESCEND study is that suicidal ideation is more closely associated with anxious depression than non-anxious depression.50 Hence, it is remarkable that emotional withdrawal, tension, and suicidal ideation are distinctive clinical correlates of PMD. These findings suggest that psychotic features are sufficient for diagnosing PMD, and can occur in MDD regardless of severity of depressive symptoms. Thus, these findings also support the view that PMD meets the criteria for a distinctive psychiatric disease entity, which has its own clinical presentation and course.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is possible that the small number of PMD subjects had an impact on statistical significance. Second, we did not evaluate psychiatric comorbidities, and as such, influence of psychiatric comorbidity on the status of PMD was not analyzed. Third, the cognitive symptoms and clinical course of the PMD subjects was not investigated. Fourth, the clinical significance of the statistical differences between PMD and NPMD subjects could be minimal; it is possible that these effects could be secondary consequences of the large sample size, although statistical significance was set at p<0.01 (two-tailed) for all tests. Fifth, interrater reliabilities were not conducted in our study. In spite of these limitations, our study has a number of virtues. The data used were from the CRESCEND study, which is the largest depression cohort study conducted in Asian countries and reveals sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of PMD subjects, unlike studies conducted in Western countries. Distinctive clinical correlates of PMD vs. NPMD that emerged from our study of Korean depressed patients should contribute to the formulation of a psychiatric nosological hierarchy of PMD.

Although a diagnosis of PMD is rarely made in clinical psychiatry, it is believed that it is a relatively common psychiatric illness. Using data from the CRESCEND study, we defined the prevalence and distinctive clinical correlates of PMD in a large cohort of Korean subjects with depression. PMD was specifically correlated with tension, excitement and suicidal ideation. These findings lend support to the view that PMD is a disease entity, which has its own distinctive clinical features and is distinct from NPMD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health 21 R&D, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A102065).

References

- 1.Hwang SH, Rhee MK, Kang RH, Lee HY, Ham BJ, Lee YS, et al. Development of validation of a screening scale for depression in Korea: the Lee and Rhee depression scale. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9:36–44. doi: 10.4306/pi.2012.9.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jang SH, Park YN, Jae YM, Jun TY, Lee MS, Kim JM, et al. The symptom frequency characteristics of the Hamilton depression rating scale and possible symptom clusters of depressive disorders in Korea: The CRESCEND study. Psychiatry Investig. 2011;8:312–319. doi: 10.4306/pi.2011.8.4.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF. Prevalence of depressive episodes with psychotic features in the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1855–1861. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson J, Horwath E, Weissman MM. The validity of major depressive disorder with psychotic features based on a community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1075–1081. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360039006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coryell W, Pfohl B, Zimmerman M. The clinical and neuroendocrine features of psychotic depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984;172:521–528. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ. Psychotic (delusional) major depression: should it be included as a distinct syndrome in DSM-IV? Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:733–745. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Østergaard SD, Rothschild AJ, Uggerby P, Munk-Jørgensen P, Bech P, Mors O. Considerations on the ICD-11: classification of psychotic depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81:135–144. doi: 10.1159/000334487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Østergaard SD, Bille J, Søltoft-Jensen H, Lauge N, Bech P. The validity of the severity-psychosis hypothesis in depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lykouras E, Malliaras D, Christodoulou GN, Papakostat Y, Voulgari A, Tzonou A, et al. Delusional depression: phenomenology and response to treatment: a prospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;73:324–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothschild AJ, Benes F, Hebben N, Woods B, Luciana M, Bakanas E, et al. Relationships between brain CT scan findings and cortisol in psychotic and nonpsychotic depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;26:565–575. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charney DS, Nelson JC. Delusional and nondelusional unipolar depression: further evidence for distinctive subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:328–333. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glassman AH, Roose SP. Delusional depression: a distinct clinical entity? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:424–427. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290058006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Hickie I, Boyce P, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, et al. Distinguishing psychotic and non-psychotic melancholia. J Affect Disord. 1991;22:135–148. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90047-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TS, Jeong SH, Kim JB, Lee MS, Kim JM, Yim HW, et al. The clinical research center for depression study: baseline characteristics of a Korean long-term hospital-based observational collaborative prospective cohort study. Psychiatry Investig. 2011;8:1–8. doi: 10.4306/pi.2011.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Wiliams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:779–812. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton MA. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton MA. The assessment of anxiety state by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy W. Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication. Washington DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1148–1156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi JS, Bae SO, Ahn YM, Park DB, Noh KS, Shin HK, et al. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (K-HDRS) J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2005;44:456–465. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JY, Cho MJ, Kwon JS. Global assessment of functioning scale and social and occupational functioning scale. Korean J Psychopharmacol. 2006;17:122–127. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overall JE, Beller SA. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) in geropsychiatric research: I. factor structure on inpatient unit. J Gerontol. 1984;39:187–193. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaudiano BA, Miller IW, Herbert JD. The treatment of psychotic major depression: is there a role for adjunctive psychotherapy. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:271–277. doi: 10.1159/000104703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musalek M, Berner P, Katsching H. Delusional theme, sex and age. Psychopathology. 1989;22:260–267. doi: 10.1159/000284606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ndetei DM, Vadher A. A comparative cross-cultural study of the frequencies of hallucination in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1984;70:545–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1984.tb01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devylder JE, Oh HY, Yang LH, Cabassa LJ, Chen FP, Lukens EP. Acculturative stress and psychotic-like experiences among Asian and Latino immigrants to the United States. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller J, Gomez RG, Kenna HA, Poesner J, DeBasttista C, Flores B, et al. Detecting psychotic major depression using psychiatric rating scales. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaudiano BA, Dalrymle Kl, Zimmerman M. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of psychotic versus nonpsychotic major depression in a general psychiatric clinic. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:54–64. doi: 10.1002/da.20470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen CI, Marino L. Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in the general population. Psychiatr Serv. 2013 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200348. inpress. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roh S, Park YC. Characteristics of depression in Korea and non-pharmacological treatment. Korean J Biol Psychiatry. 2006;13:226–233. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park YC, Park SC. Why do suicide and depression occur? J Korean Med Assoc. 2012;55:329–334. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vythilingam M, Chen J, Bremmer JD, Mazure CM, Maciejewski PK, Nelson JC. Psychotic depression and mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:574–576. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coryell W, Leon A, Winokur G, Endicott J, Keller M, Akiskal H, et al. Importance of psychotic feature to long-term course in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:483–489. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaffer A, Flint AJ, Smith E, Rothschild AJ, Mulsant BH, Szanto K, et al. Correlates of suicidality among patients with psychotic depression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38:403–414. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Black DW, Winokur G, Nasrallah A, Brewin A. Psychotic symptoms and age of onset in affective disorders. Psychopathology. 1992;25:19–22. doi: 10.1159/000284749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gournellis R, Oulis P, Rizos E, Chourdaki E, Gouzaris A, Lykouras L. Clinical correlates of age of onset in psychotic depression. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Power RA, Keers R, Ng MY, Butler AW, Uher R, Cohen-Woods S, et al. Dissecting the genetic heterogeneity of depression through age at onset. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B:859–868. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akiskal HS, Walker P, Puzantin VR, King D, Rosenthal TL, Dranon M. Bipolar outcome in the course of depressive illness. Phenomenologic, familial, and pharmacological predictors. J Affect Disord. 1983;5:115–128. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(83)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strober M, Carlson G. Bipolar illness in adolescents with major depression: clinical, genetic, and psychopharmacological predictors in a three- to four-year prospective follow-up investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:549–555. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290050029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaudiano BA, Young D, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Depressive symptom profiles and severity patterns in outpatients with psychotic vs nonpsychotic major depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keller J, Schatzberg AF, Maj M. Current issues in the classification of psychotic major depression. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:877–885. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thakur M, Hays J, Krishnan KR. Clinical, demographic and social characteristics of psychotic depression. Psychiatry Res. 1999;86:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg JF, Harrow M. Subjective life satisfaction and objective functional outcome in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders: a longitudinal analysis. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulford D, Tuchman N, Johnson SL. The Cognition Checklist for Mania-Revised (CCL-M-R): factor-analytic structure and links with risk for mania, diagnoses of mania, and current Symptoms. Int J Cogn Ther. 2009;2:313–324. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2009.2.4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serretti A, Mandelli L, Lorenzi C, Pirovano A, Olgiati P, Colombo C, et al. Serotonin transporter gene influences the time course of improvement of "core" depressive and somatic anxiety symptoms during treatment with SSRIs for recurrent mood disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seo HJ, Jung YE, Kim TS, Kim JB, Lee MS, Kim JM, et al. Distinctive clinical characteristics and suicidal tendencies of patients with anxious depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:42–48. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182043b60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]