Abstract

Background

This study aimed to examine the therapeutic effect and prognostic indicators of pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) combination therapy in thrombocytopenic patients with chronic hepatitis C, hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis, and those who underwent splenectomy or partial splenic embolization (PSE).

Methods

Of 326 patients with HCV-related chronic liver disease (252 with genotype 1b and 74 with genotype 2a/2b) treated with PEG-IFN/RBV, 90 were diagnosed with cirrhosis.

Results

Regardless of the degree of thrombocytopenia, the administration rate was significantly higher in the splenectomy/PSE group compared to the cirrhosis group. However, in patients with genotype 1b, the sustained virological response (SVR) rate was significantly lower in the cirrhosis and the splenectomy/PSE groups compared to the chronic hepatitis group. No cirrhotic patients with platelets less than 80,000 achieved an SVR. Patients with genotype 2a/2b were more likely to achieve an SVR than genotype 1b. Prognostic factors for SVR in patients with genotype 1b included the absence of esophageal and gastric varices, high serum ALT, low AST/ALT ratio, and the major homo type of the IL28B gene. Splenectomy- or PSE-facilitated induction of IFN in patients with genotype 2a/2b was more likely to achieve an SVR by an IFN dose maintenance regimen. Patients with genotype 1b have a low SVR regardless of splenectomy/PSE. In particular, patients with a hetero/minor type of IL28B did not have an SVR.

Conclusions

Splenectomy/PSE for IFN therapy should be performed in patients expected to achieve a treatment response, considering their genotype and IL28B.

Keywords: IFN therapy, IL28B, Partial splenic embolization, Splenectomy, Thrombocytopenia

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C is characterized by recurrent necrosis and regeneration in the setting of persistent inflammation, leading to progressive hepatic fibrosis, which increases the risk of carcinogenesis. In cirrhotic livers, cancer develops at a higher rate [1, 2]. However, after a virus has been removed by interferon (IFN) therapy, hepatic fibrosis can improve, and the incidence of liver cancer is subsequently reduced [3–5]. Therefore, to prevent fibrosis and liver carcinogenesis, virus elimination by antiviral therapies is paramount in advanced cases.

As an antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C, pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) in combination with ribavirin (RBV) has resulted in remarkably favorable outcomes, with a sustained virological response (SVR) obtained in approximately 80 % of patients with genotypes 2 and 3 and, more impressively, 40–50 % of patients with genotype 1 and a refractory high viral load [6–9].

As fibrosis progresses, however, the therapeutic effect of antivirals diminishes. Studies have reported that the effect of PEG-IFN/RBV combination therapy for liver cirrhosis characterized by progressive fibrosis was exceedingly poor, with the SVR rates 14–27 % in patients with genotype 1 and 33–56 % in patients with genotypes 2 and 3 [10–12].

It is very important to maintain the IFN dose as the administration rate in addition to the presence of fibrosis greatly influences the therapeutic effect [13, 14]. However, it can be difficult to maintain the IFN dose in patients with cirrhosis complicated by hypersplenism. Thrombocytopenia from hypersplenism can develop and/or be exacerbated following IFN therapy, making ongoing therapy problematic. In addition, the induction of IFN therapy may be difficult in some of these patients [15, 16]. Hence, to address cytopenias including thrombocytopenia, splenectomy or partial splenic embolization (PSE) can be performed for hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis with hypersplenism [17–23]. However, the therapeutic effect and long-term safety and efficacy of such treatment have not been sufficiently examined.

Recently, studies have reported that the interferon sensitivity-determining region (ISDR) and amino acid substitutions of core 70 and core 91 in the core region of HCV are important prognostic indicators of IFN’s therapeutic effect. Furthermore, the therapeutic effect rate of IFN depends on the genetic polymorphism of IL28B [24–29].

The objectives of this study were to examine the therapeutic effect and associated prognostic indicators of PEG-IFN/RBV therapy in thrombocytopenic patients with chronic hepatitis and HCV-related cirrhosis and those who underwent splenectomy or PSE.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hyogo College of Medicine (approval no. 92, 391) and adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients after the objectives and nature of the study had been discussed.

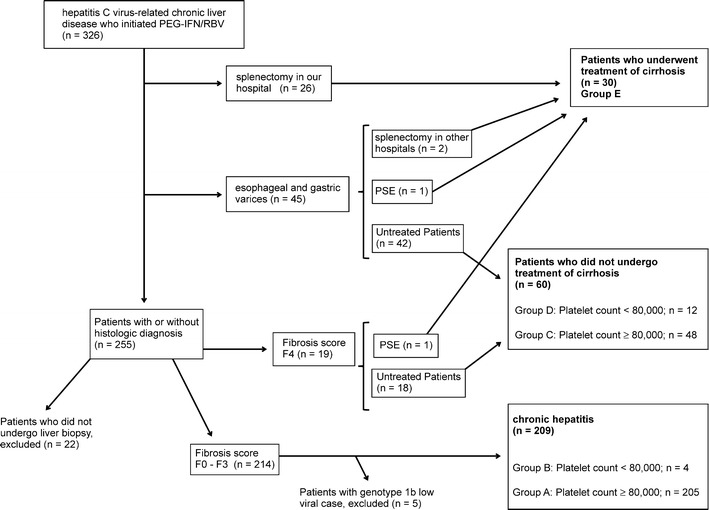

Between January 2005 to 2012, 326 patients with HCV-related chronic liver disease who were started on PEG-IFN/RBV combination therapy and followed at the Hyogo College of Medicine Hospital were enrolled in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study patients

Twenty-six patients were diagnosed with cirrhosis macroscopically when they underwent splenectomy in our hospital. Of 45 patients with esophageal and gastric varices and diagnosed with cirrhosis on abdominal imaging, two underwent splenectomy in other hospitals, and one underwent PSE prior to IFN therapy.

Of the remaining 255 patients, 22 patients who did not undergo liver biopsy were excluded from the study, 233 patients underwent a liver biopsy, and 19 were diagnosed to have cirrhosis histologically. One of the 19 patients subsequently underwent PSE prior to IFN therapy. In total, there were 90 patients diagnosed with cirrhosis in this study. The 30 patients with cirrhosis who underwent splenectomy or PSE (treated cirrhosis group) were compared to the 60 patients who did not have either procedure (untreated cirrhosis group).

Of the 233 patients who had a liver biopsy, 214 did not have histological diagnosis of cirrhosis. Five patients with genotype 1b low viral load (HCV-RNA <100 K IU/ml) in the chronic hepatitis group were excluded from this study because there were no patients with genotype 1b low viral load in the corresponding cirrhosis group.

There were 43 patients (4, 12, and 27 patients in group B, D, and E, respectively) with a platelet count of less than 80,000 prior to the initiation of IFN therapy. They were fully informed aboout the expected benefits and associated risks of splenectomy or PSE. Twenty-five consented to splenectomy, while another two chose to undergo PSE prior to IFN therapy.

One patient with a platelet count of slightly more than 80,000 requested to undergo splenectomy. Therefore, we initiated IFN therapy in this patient and considered the patient in the treated group analysis in this study. With regard to the two patients who had already undergone splenectomy for portal hypertension in other hospitals, although their lowest platelet counts prior to splenectomy were unknown, they were nevertheless also included in the treated group.

Patients with uncontrolled ascites, liver cancer, esophageal, and/or gastric varices requiring treatment and those who underwent liver transplantation were excluded from this study. Patients with positive hepatitis B virus surface antigen, positive human immunodeficiency virus antigen, or other hepatic disorders (e.g., primary biliary cirrhosis or autoimmune hepatitis) were also excluded.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 299 patients (groups A, B, C, D, and E; see Fig. 1) prior to IFN therapy. Blood work before splenectomy or PSE is also provided for those who underwent these procedures.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Factor | Value (range or number) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic hepatitis (n = 209) | Liver cirrhosis (n = 60) | PSE or splenectomy (n = 30) | |

| Sex (male/female) (cases) | 90/119 | 35/25 | 16/14 |

| Mean age/range (years) | 57.9 ± 11.2 | 62.7 ± 9.2 | 61.0 ± 7.1 |

| White blood cells (/mm3) | 4,648.8 ± 1,613.8 | 4,068.3 ± 1,156.2 | 3,410.4 ± 1,268.3a |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.8 ± 1.5 | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 12.5 ± 2.2a |

| Platelet count (×104/mm3) | 16.2 ± 4.9 | 11.2 ± 3.0 | 6.0 ± 1.4a |

| AST (IU/l) | 47.2 ± 32.4 | 77.2 ± 47.1 | 58.0 ± 24.2a |

| ALT (IU/l) | 57.9 ± 51.8 | 82.3 ± 58.9 | 54.8 ± 24.9a |

| AST/ALT | 0.94 ± 0.29 | 1.01 ± 0.25 | 1.12 ± 0.30a |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5a |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.5a |

| PT percentage activity (%) | 94.6 ± 10.0 | 83.5 ± 8.9 | 80.6 ± 13.2a |

| Associated esophageal varices (cases) (present/absent) | 0/209 | 42/18 | 18/12 |

| History of treatment for HCC (cases) (with or without) | 9/200 | 19/41 | 6/24 |

| Previous treatment of IFN (cases) with or without) | 81/128 | 30/30 | 24/6 |

| HCV genotype (1b/2a/2b/2a + 2b/2a or 2b) (cases) | 153/31/22/3/0 | 50/6/3/0/1 | 25/4/1/0/0 |

| HCV-RNA (KIU/ml) | |||

| 100 ≤ HCV-RNA < 1,000 KIU/ml (cases) | 64 | 19 | 10 |

| ≥1,000 KIU/ml (cases) | 145 | 41 | 20 |

| Amino acid substitutions in the HCV genotype 1b | (n = 153) | (n = 50) | (n = 25) |

| Core aa 70 [arginine/glutamine (histidine)/ND] | 92/49/12 | 22/26/2 | 12/13/0 |

| Core aa 91 (leucine/methionine/ND) | 95/46/12 | 35/13/2 | 19/6/0 |

| ISDR of NS5A in the HCV genotype 1b | (n = 153) | (n = 50) | (n = 25) |

| (Wild type/non-wild type/ND) | 117/23/13 | 38/9/3 | 22/3/0 |

| Genetic variation near IL28B gene(rs 8099917) in patients with genotype 1b | (n = 153) | (n = 50) | (n = 25) |

| (TT/TG/GG/ND) | 81/42/4/26 | 29/17/1/3 | 16/9/0/0 |

AST Aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST/ALT aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio, ND not determined

aWe excluded two patients who had already undergone splenectomy in other hospitals because we could not obtain their data before splenectomy

Treatment for hepatitis C virus

Peginterferon alpha-2a (Pegasys®; Chugai, Japan) was administered to 113 patients, and 186 were treated with peginterferon alpha-2b (Pegintron®; MSD, Japan). The basic dose each week was either 180 μg of peginterferon alpha-2a or 1.0–1.5 μg/kg of peginterferon alpha-2b. RBV combination therapy was also given to all patients and was administered orally each day at a basic dose depending on body weight (<60 kg, 600 mg; 60–80 kg, 800 mg; >80 kg, 1,000 mg).

Patients with genotype 1b and 2a/2b were treated for 48 and 24 weeks, respectively. Based on the patient request, 106 with genotype 1b were treated for 50–90 weeks, and 34 with genotype 2a/2b were treated for 30–72 weeks.

Laboratory and histological tests

The amount of HCV was measured by COBAS AMPLICOR HCV MONITOR test, version 2.0 (detection range 6–5000 K IU/ml; Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ, USA). Qualitative analysis was performed using COBAS AMPLICOR HCV test, version 2.0 (lower limit of detection 50 IU/ml; Roche Diagnostics). For patients who started IFN therapy after January 2008, the amount of HCV was measured by COBAS TaqMan HCV test (Roche Diagnostics). Six months after completing treatment, patients with negative HCV RNA were considered to have an SVR.

ISDR, Core 70, and Core 91 were measured by the direct sequencing method, as previously reported [23, 24]. The IL28B gene (rs 8099917) was measured using the TaqMan probe method, as previously reported [25].

Histological assessment of fibrosis was scored using the METAVIR scoring system: F0, no fibrosis; F1, mild fibrosis or portal fibrosis without septa; F2, moderate fibrosis or few septa; F3, severe fibrosis or numerous septa without cirrhosis; F4, cirrhosis.

Study analysis

We recently reported a nationwide survey in Japan regarding splenectomy/PSE for interferon treatment targeting HCV-related chronic liver disease in patients with low platelet counts. We found that many patients with platelet counts <80,000 were treated with a reduced dose of IFN, at which the SVR rate was predicted to be low [30]. Therefore, we classified the patients with platelet counts of 80,000 in the present study. Before IFN therapy, patients with chronic hepatitis who had the lowest platelet count of at least 80,000 were assigned to group A, whereas those with a platelet count of less than 80,000 were placed in group B. Patients with liver cirrhosis who had platelet counts of at least 80,000 before IFN therapy were assigned to group C, whereas those with platelet counts of less than 80,000 before IFN therapy were placed in group D. Group E comprised patients who received IFN therapy after splenectomy or PSE (Fig. 1). The IFN administration rate was examined according to each group. Treatment was discontinued in patients who failed to demonstrate virus-negative results by 24 weeks. Therefore, the IFN dose was evaluated using the dose administered until 24 weeks. The normal dose each week was either 180 μg of peginterferon alpha-2a or 1.5 μg/kg of peginterferon alpha-2b. The actual dose rate was evaluated as <50, 50–80, and 80 % or more of the normal dose.

The SVR rate in each group was examined according to genotype. In group E, biochemical tests before and after splenectomy or PSE were compared.

In the liver cirrhosis groups, the factors contributing to SVR were examined in those with genotype 1 and a high viral load.

Statistical analysis

Baseline data are expressed as mean ± SD or median values. Virologic response was evaluated using the full analysis set (FAS). In patients who underwent splenectomy or PSE, pre- and postoperative blood work was compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The IFN administration rate was compared using the chi-square test.

To compare SVRs, the patient characteristics were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, chi-square test, or Fisher's exact probability test.

All statistical analyses were performed using Jump version 9.0 software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Pre- and postoperative blood work for splenectomy or PSE

Although we enrolled a total of 30 patients who underwent splenectomy/PSE, we excluded two patients who had already undergone splenectomy in other hospitals because we could not obtain their data before splenectomy. Table 2 compares the pre- and postoperative blood work of the 28 patients who underwent splenectomy or PSE in our hospital. Twenty-six underwent splenectomy, and two had PSE. White blood cell and platelet counts increased significantly from 3,410 ± 1,268 to 5,126 ± 1,337/mm3 (P < 0.0001) and from 6.0 ± 1.4 × 104 to 16.7 ± 5.1 × 104/mm3 (P < 0.0001), respectively. Furthermore, total bilirubin (T-Bil) and PT significantly improved from 1.2 ± 0.5 mg/dl to 0.9 ± 0.5 mg/dl (P = 0.0004) and from 80.6 ± 13.2 to 84.2 ± 9.2 % (P = 0.0153), respectively.

Table 2.

Clinical data of patients who underwent PSE or splenectomy

| Before PSE or splenectomy (n = 28) | After PSE or splenectomy (n = 28) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (/mm3) | 3,410 ± 1,268 | 5,126 ± 1,337 | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.5 ± 2.2 | 12.2 ± 1.9 | 0.3736 |

| Platelet count (×104/mm3) | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 16.7 ± 5.1 | <0.0001 |

| AST (IU/l) | 58.0 ± 24.2 | 65.5 ± 31.6 | 0.0849 |

| ALT (IU/l) | 54.8 ± 24.9 | 54.9 ± 32.3 | 0.7155 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.0004 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 0.8030 |

| PT percentage activity (%) | 80.6 ± 13.2 | 84.2 ± 9.2 | 0.0153 |

AST Aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase

The IFN dose

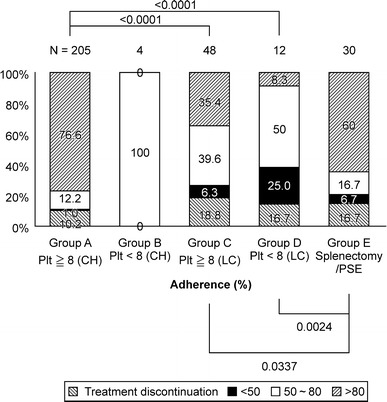

Figure 2 shows the IFN dose until 24 weeks based on platelet counts.

Fig. 2.

The IFN dose until 24 weeks according to platelet count. The actual IFN dose rate until 24 weeks was evaluated as less than 50, 50–80, and 80 % of the normal dose. Group A, chronic hepatitis (plt ≥8); group B, chronic hepatitis (plt <8); group C, untreated cirrhosis group (plt ≥8); group D, untreated cirrhosis group (plt <8); group E, splenectomy/PSE

Patients given 80 % or more of the normal dose constituted 76.6 % (157/205 patients), 0 % (0/4 patients), 35.4 % (17/48 patients), 8.3 % (1/12 patients), and 60.0 % (18/30 patients) of groups A, B, C, D, and E, respectively. The administration rates in groups C and D were significantly lower compared to group A (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, respectively). Also, the administration rates in cirrhotic patients in group E were significantly improved compared to those in groups C and D who did not undergo either procedure (P = 0.0337, P = 0.0024, respectively).

Virologic response

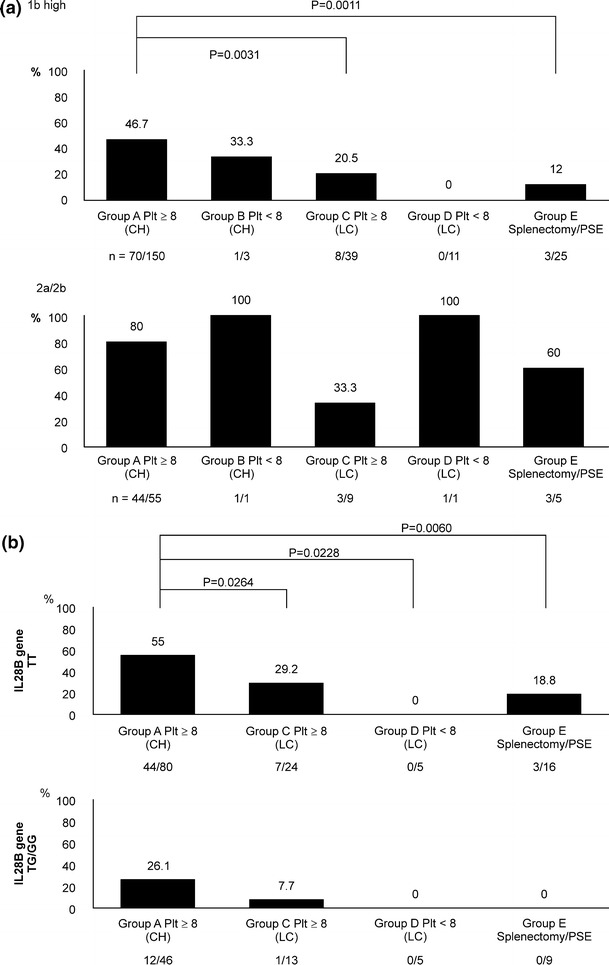

Figure 3a shows the virologic response to PEG-IFN/RBV therapy.

Fig. 3.

a The sustained virological response (SVR) rate. b The SVR rate based on the IL28B genotype in patients with genotype 1b and high viral load. Twenty-five, two, and one patient from groups A, C, and D, respectively, were excluded because their IL28B genotype was not measured. Group B patients were excluded because only two patients underwent the examination

The SVR rates of patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load and patients with genotype 2a/2b were 36.0 % (82/228 patients) and 73.2 % (52/71 patients), respectively.

In chronic hepatitis groups A and B, the SVR rates of patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load and patients with genotype 2a/2b were 46.4 % (71/153 patients) and 80.4 % (45/56 patients), respectively.

In the cirrhosis groups C, D, and E, the SVR rates of patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load and patients with genotype 2a/2b were 14.7 % (11/75 patients) and 46.7 % (7/15 patients), respectively.

In both patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load and patients with genotype 2a/2b, the SVR rates of the cirrhosis group were significantly lower than those of the chronic hepatitis group (P < 0.00001, P = 0.009, respectively).

In patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load, the SVR rates in groups A, B, C, D, and E were 46.7 % (70/150 patients), 33.3 % (1/3 patients), 20.5 % (8/39 patients), 0 % (0/11 patients), and 12.0 % (3/25 patients), respectively.

In patients with genotype 2a/2b, the SVR rates in groups A, B, C, D, and E were 80.0 % (44/55 patients), 100 % (1/1 patient), 33.3 % (3/9 patients), 100 % (1/1 patient), and 60.0 % (3/5 patients), respectively.

Prognostic factors for SVR in HCV-related cirrhotic patients with genotype 1b

In patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load in the cirrhosis group, patient characteristics were compared between those who did (SVR group) and those who did not achieve an SVR (non-SVR group) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis: factors predictive of sustained virological response in cirrhotic patients with genotype 1b

| Factor | Value (range or number) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SVR n = 11 |

Non-SVR n = 64 |

P value | |

| Sex (male/female) (cases) | 5/6 | 28/36 | 0.916 |

| Mean age/range (years) | 62.5 ± 9.2 | 61.6 ± 8.6 | 0.664 |

| White blood cells (/mm3) | 4,042.7 ± 1,377.4 | 3,930.0 ± 1,154.8 | 0.811 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.1 ± 1.4 | 12.9 ± 1.8 | 0.632 |

| Platelet count (×104/mm3) | 10.6 ± 2.8 | 9.4 ± 3.7 | 0.185 |

| AST (IU/l) | 86.8 ± 4.3 | 63.0 ± 33.0 | 0.119 |

| ALT (IU/l) | 112.6 ± 92.9 | 66.5 ± 38.0 | 0.027 |

| AST/ALT | 0.85 ± 0.17 | 1.04 ± 0.27 | 0.022 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.306 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 0.382 |

| PT percentage activity (%) | 88.4 ± 11.6 | 82.1 ± 9.3 | 0.137 |

| Associated esophageal varices (cases) (present/absent) | 3/8 | 44/20 | 0.009 |

| History of treatment for HCC (cases) (with or without) | 2/9 | 19/45 | 0.432 |

| Previous treatment of IFN (cases) (with or without) | 6/5 | 38/26 | 0.764 |

| HCV-RNA (KIU/ml) | |||

| Low level (<1,000 KIU/ml) (cases) | 2 | 20 | |

| High level (≥1,000 KIU/ml) (cases) | 9 | 44 | 0.379 |

| ISDR (wild type/non-wild type)/ND | 7/3/1 | 53/9/2 | 0.223 |

| Core aa 70 [arginine/glutamine (histidine)]/ND | 5/5/1 | 33/30/1 | 0.889 |

| Core aa 91 (leucine/methionine)/ND | 8/2/1 | 46/17/1 | 0.640 |

| IL28B (rs 8099917) TT/TG or GG/ND | 10/1/0 | 35/26/3 | 0.035 |

AST Aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST/ALT aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio, ND not determined

Comparing the numbers of patients with esophageal and gastric varices, there were significantly fewer patients with these varices in the SVR group compared to the non-SVR group (3/11 vs. 44/64, P = 0.009). With regard to liver enzymes, serum alanine aminotransferase was significantly higher in the SVR group compared to that of the non-SVR group (112.6 ± 92.9 IU/l vs. 66.5 ± 38.0 IU/l, P = 0.027). Furthermore, the AST/ALT ratio was significantly lower in the SVR group compared to the non-SVR group (0.85 ± 0.17 vs. 1.04 ± 0.27, P = 0.022).

The SVR group was significantly more likely to carry the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism compared to the non-SVR group (10/11 vs. 35/61, P = 0.035).

In patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load, the IL28B genetic polymorphism and therapeutic effect rate were examined according to the chronic hepatitis group, the untreated cirrhosis group, and the splenectomy or PSE group (Fig. 3b).

For patients in the chronic hepatitis group with a platelet count of at least 80,000, the SVR rate in those with the major homo(TT) allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism was 55 % (44/80 patients) compared to 26.1 % (12/46 patients) in those with the hetero/minor(TG/GG) allele. For patients in the cirrhosis group with a platelet count of at least 80,000, the SVR rate in patients with the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism was 29.2 % (7/24 patients) compared to 7.7 % (1/13 patients) in those with the TG/GG allele. Patients with a platelet count of less than 80,000 did not achieve an SVR, independent of whether they had the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism or the TG/GG allele.

In contrast, in patients who underwent splenectomy or PSE, the SVR rate was 18.8 % (3/16 patients) in patients with the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism, although 0 % (0/9 patients) in patients with the TG/GG allele.

Patients who discontinued IFN therapy

In the chronic hepatitis group, 169 patients completed IFN therapy while 40 patients discontinued it. In the cirrhosis group, 49 patients completed IFN therapy while 41 patients discontinued it.

Reasons for withdrawal from treatment are shown in Table 4. In the cirrhosis group, treatment was discontinued in ten patients because they did not have virus-negative results by 24 weeks after starting IFN/RBV therapy. Another 11 patients developed liver cancer during treatment, and 1 patient died due to other factors. Nineteen patients ceased treatment because of side effects, which accounted for 21.1 % of 90 patients with cirrhosis who underwent the treatment. There were no serious adverse side effects reported.

Table 4.

Main causes of treatment discontinuation

| Cause of discontinuation | No. of patient | |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic hepatitis (n = 209) | Cirrhosis (n = 90) | |

| Fatigue | 6 | 5 |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 3 |

| Anemia | 0 | 1 |

| Fundal hemorrhage | 1 | 2 |

| Auditory disturbance | 1 | 1 |

| Suspicion of interstitial pneumonia | 2 | 2 |

| Dizziness | 3 | 0 |

| Pruriris | 5 | 1 |

| Depression | 2 | 1 |

| Presyncope | 1 | 1 |

| Liver function flare | 1 | 1 |

| Infection | 0 | 1 |

| No virological response | 13 | 10 |

| HCC occurrence | 2 | 11 |

| Death of accident | 0 | 1 |

| Patient’s reasons | 1 | 0 |

Discussion

In PEG-IFN/RBV therapy for chronic hepatitis C, the SVR rate decreased in the setting of progressive fibrosis. Treatment outcomes for HCV-related cirrhosis describe low SVR rates [10–12]. In this study, in the chronic hepatitis group, the SVR rates of PEG-IFN/RBV therapy in patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load and patients with genotype 2a/2b were 46.4 and 80.4 %, respectively. In comparison, in the cirrhosis group, the SVR rates in patients with genotype 1b and patients with genotype 2a/2b were 14.7 and 46.7 %, respectively, indicating a significantly poorer therapeutic effect.

Adherence to IFN therapy is important to achieve a therapeutic effect. It has been suggested that 80 % or more of the basic dose should be administered [13, 14]. However, patients with cirrhosis complicated by hypersplenism have thrombocytopenia, and it becomes exceedingly difficult to initiate IFN therapy and achieve an adequate therapeutic adherence. Due to ongoing thrombocytopenia, which may fall below the recommended level for therapy cessation, the therapeutic effect will therefore not be obtained.

In this study, in the chronic hepatitis group, we were able to maintain 80 % or more of the IFN dose in 76.6 % of patients with a platelet count of 80,000 or more. In this group, the SVR rates were 46.7 and 80.0 % in patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load and patients with genotype 2a/2b, respectively, which were relatively better results.

However, the cirrhosis group showed low adherence; 35.4 % of the patients with a platelet count of 80,000 or more were maintained on 80 % or more of the IFN dose. The SVR rates were 20.5 and 33.3 % in patients with genotype 1b and high viral load and patients with genotype 2a/2b, demonstrating a low therapeutic effect rate. In other words, in the cirrhosis group, there was a decreased adherence and therapeutic effect rate despite sufficient levels of platelets prior to IFN therapy.

Furthermore, in the cirrhosis group, the administration rate was ever lower in patients with a platelet count of less than 80,000. Only 8.3 % of these patients maintained 80 % of the IFN dose. No patients achieved an SVR among the patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load. We found that the platelet count was an important factor for maintaining the IFN dose maintenance regimen and influenced the therapeutic effect rate.

In addition, cytopenia including thrombocytopenia greatly prevents the induction of IFN therapy [16]. Although our study did not examine this specifically, we hypothesize that many patients likely found it difficult to initiate IFN therapy because of thrombocytopenia.

Our study included eight patients with a platelet count of less than 50,000, and splenectomy or PSE allowed all of them to initiate IFN therapy. These procedures also improved the platelet count and allowed 18 of the total 30 (60.0 %) who underwent these procedures to maintain 80 % or more of the IFN dose for 24 weeks or more. The IFN dose maintenance regimen was very acceptable in the treated group compared to the untreated group. However, in patients with genotype 1b in the treated group, the SVR rate was low at 12.0 %, and the therapeutic effect rate failed to improve. Although we cannot completely clarify why the improvement of drug adherence did not result in a favorable outcome, the presence of advanced liver fibrosis and its related portal hypertension could also influence the SVR rate, as well as the adherence to IFN therapy.

It was difficult to evaluate patients with genotype 2a/2b because they were few in number. Nevertheless, the SVR rate slightly improved by 60 % (3/5 patients) in the treated group when compared to the untreated group.

Recently, ISDR and amino acid substitutions of core 70 and core 91 in the core region of HCV have been reported as factors associated with the therapeutic effect of PEG-IFN/RBV combination therapy for patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load [24, 25]. In the human genome, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) of IL28B is an important factor [26–28]. Therefore, these factors were included in our analysis of prognostic factors for a therapeutic effect leading to SVR in patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load. In our study, this group had experienced a poor therapeutic effect, especially in comparison to patients with genotype 2a/2b.

Univariate analysis revealed that there were significantly more patients with esophageal and gastric varices in the non-SVR group than in the SVR group. Furthermore, patients with a higher serum aspartate aminotransferase and lower AST/ALT ratio were more likely to achieve an SVR. Hence, we considered that in the cirrhosis group, the therapeutic effect rate was decreased in patients who develop fibrosis of the liver with portal hypertension. In addition, significantly more patients who achieved an SVR had the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism than the TG/GG allele.

In the multivariate analysis, SVR was associated with patients without esophageal varices [odds ratio, 11.02; 95 % confidence interval (CI), 2.058–99.979; P = 0.0038] and patients with the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism (odds ratio, 16.4; 95 % CI, 1.870 to −426.906; P = 0.0085; results not shown in this study because the 95 % confidence interval was too large).

In patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load, the therapeutic effect rate was low even in those with the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism. This therapeutic effect rate did not improve despite splenectomy or PSE performed to improve adherence to IFN therapy. In patients with the TG/GG allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism, treatment outcomes were even worse. In the cirrhosis group, low adherence contributed to a poor therapeutic effect of IFN. However, improving adherence alone will not directly lead to an improved SVR rate.

Splenectomy or PSE does carry procedural-related risks, and there have been case reports of death caused by infection during IFN therapy. Hence, splenectomy or PSE appears to be indicated for the purpose of IFN therapy in patients with genotype 2a/2b who are more likely to achieve an SVR by dose maintenance. In this study, we investigated the patients who received PEG-IFN/RBV combination therapy. There were five chronic hepatitis patients with genotype 1b and a low viral load, while there were no patients with genotype 1b and a low viral load in the cirrhosis groups (groups C, D, and E). We therefore could not compare the data of the patients with genotype 1b and a low viral load between the chronic hepatitis groups and the cirrhosis groups. However, splenectomy or PSE may also be indicated in patients with genotype 1b and a low viral load. For patients with genotype 1b and a high viral load, these procedures may be indicated in patients with the TT allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism.

In general, there are several differences in the pre- and post-hematologic parameters between PSE and splenectomy. However, we were not able to evaluate the effect of splenectomy separately from that of PSE because there were only two patients who received PSE in this study. Additionally, medications to treat thrombocytosis include Eltrombopag, a thrombopoietin receptor agonist used for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. A case has been reported detailing the benefit of Eltrombopag on the therapeutic effect of IFN in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis found to be thrombocytopenic [31]. Further studies are required to examine which procedure or medication, be it splenectomy, PSE, or Eltrombopag, best ameliorates thrombocytopenia prior to IFN therapy.

In recent years, direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have been used as novel anti-HCV drugs, greatly altering the therapeutic strategy for chronic hepatitis C. In Japan, telaprevir (TVR) has been used in patients with chronic hepatitis C (patients with genotype 1 and a high viral load), and three agents (TVR/PEG-IFNα-2b/RBV) in combination therapy have been used since November 2011. About 90 % of patients who experience a relapse following pretreatment or patients with the TT allele of IL28B in particular achieved an SVR, indicating dramatically improved effectiveness in treatment [32]. However, there are various issues with TVR. Currently, it is not indicated in patients with cirrhosis, and its therapeutic effect is suboptimal for those who did not respond to pretreatment and patients with the TG/GG allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism. Furthermore, more patients choose to discontinue treatment because of side effects compared to those treated with PEG-IFN/RBV combination therapy. A clinical trial of the second-generation protease inhibitor is ongoing. It is expected that the therapeutic effect and tolerability of this medication will be improved.

IFN can be difficult to initiate in patients with cirrhosis, which may be the initial cause for cytopenia. Cytopenia can occur as a side effect of IFN treatment, but the blood cells are only slightly decreased because of PEG-IFN lambda/RBV combination therapy since the receptor for IFN-λ is not found in hematopoietic cells [33]. Therefore, we expect that it will be indicated in patients with low platelet counts. Studies of multiple combination DAA therapy of BMS-790052 and BMS-650032 are ongoing. These studies involve patients who did not respond to pretreatment, and all of them achieved an SVR, although many have the TG/GG allele of the IL28B genetic polymorphism. It is also expected that the adverse effects will be mild, and we are optimistic that this may be suitable treatment for cirrhosis [34].

The treatment outcomes of PEG-IFN/RBV combination therapy for cirrhosis remain suboptimal. However, some patients can achieve an SVR if the treatment is completed. Furthermore, following splenectomy or PSE in thrombocytopenic patients, IFN can be initiated with subsequent improved adherence to IFN. Unfortunately, our study found a low therapeutic effect rate. Given the high number of patients who discontinued IFN therapy because of side effects or oncogenesis and considering the complications and potential death associated with splenectomy or PSE, prognostic factors such as the HCV genotype and IL28B genetic polymorphism can assist in the decision to proceed with splenectomy or PSE in patients where a good therapeutic effect can be expected.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid, no. H21-Hepatitis-General-007: “Basic and clinical research aimed at the establishment of an interferon therapy for patients with low platelets” from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

Conflict of interest

Shuhei Nishiguchi received financial support from Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ajinomoto Pharmaceuticals, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. Hiroko Iijima and Hiroyasu Imanishi received financial support from Chugai Pharmaceutical. The remaining authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Yoshida H, Shiratori Y, Moriyama M, Arakawa Y, Ide T, Sata M, et al. Interferon therapy reduces the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma: national surveillance program of cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C in Japan. IHIT Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:174–181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lok AS, Everhart JE, Wright EC, Di Bisceglie AM, Kim HY, Sterling RK, et al. Maintenance peginterferon therapy and other factors associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:840–849. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirakawa M, Ikeda K, Arase Y, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Hosaka T, et al. Hepatocarcinogenesis following HCV RNA eradication by interferon in chronic hepatitis patients. Intern Med. 2008;47:637–1643. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández-Rodríguez CM, Alonso S, Martinez SM, Forns X, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Rincón D, et al. Peginterferon plus ribavirin and sustained virological response in HCV-related cirrhosis: outcomes and factors predicting response. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2164–2172. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qu LS, Chen H, Kuai XL, Xu ZF, Jin F, Zhou GX. Effects of interferon therapy on development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C-related cirrhosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:782–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Jr, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, Muir AJ, Galler GW, McCone J, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580–593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannini EG, Basso M, Savarino V, Picciotto A. Predictive value of on-treatment response during full-dose antiviral therapy of patients with hepatitis C virus cirrhosis and portal hypertension. J Intern Med. 2009;266:537–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syed E, Rahbin N, Weiland O, Carlsson T, Oksanen A, Birk M, et al. Pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in patients with Child-Pugh Class A liver cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1378–1386. doi: 10.1080/00365520802245395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vezali E, Aghemo A, Colombo M. A review of the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in cirrhosis. Clin Ther. 2010;32:2117–2138. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(11)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, et al. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061–1069. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oze T, Hiramatsu N, Yakushijin T, Kurokawa M, Igura T, Mochizuki K, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b (Peg-IFN alpha-2b) affects early virologic response dose-dependently in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 during treatment with Peg-IFN alpha-2b plus ribavirin. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:578–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russo MW, Fried MW. Side effects of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1711–1719. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giannini EG, Marenco S, Fazio V, Pieri G, Savarino V, Picciotto A. Peripheral blood cytopaenia limiting initiation of treatment in chronic hepatitis C patients otherwise eligible for antiviral therapy. Liver Int. 2012;32:1113–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akahoshi T, Tomikawa M, Kawanaka H, Furusyo N, Kinjo N, Tsutsumi N, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy with IFN therapy in one hundred HCV-cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism and thrombocytopenia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:286–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akahoshi T, Tomikawa M, Korenaga D, Ikejiri K, Saku M, Takenaka K. Laparoscopic splenectomy with peginterferon and ribavirin therapy for patients with hepatitis C virus cirrhosis and hypersplenism. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:680–685. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikezawa K, Naito M, Yumiba T, Iwahashi K, Onishi Y, Kita H, et al. Splenectomy and antiviral treatment for thrombocytopenic patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:488–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morihara D, Kobayashi M, Ikeda K, Kawamura Y, Saneto H, Yatuji H, et al. Effectiveness of combination therapy of splenectomy and long-term interferon in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis and thrombocytopenia. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tahara H, Takagi H, Sato K, Shimada Y, Tojima H, Hirokawa T, et al. A retrospective cohort study of partial splenic embolization for antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis C with thrombocytopenia. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1010–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyake Y, Ando M, Kaji E, Toyokawa T, Nakatsu M, Hirohata M. Partial splenic embolization prior to combination therapy of interferon and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients with thrombocytopenia. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:980–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foruny JR, Blázquez J, Moreno A, Bárcena R, Gil-Grande L, Quereda C, et al. Safe use of pegylated interferon/ribavirin in hepatitis C virus cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism after partial splenic embolization. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1157–1164. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200511000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enomoto N, Sakuma I, Asahina Y, Kurosaki M, Murakami T, Yamamoto C, et al. Mutations in the nonstructural protein 5A gene and response to interferon in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus 1b infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:77–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601113340203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Someya T, et al. Association of amino acid substitution pattern in core protein of hepatitis C virus genotype 1b high viral load and non-virological response to interferon-ribavirin combination therapy. Intervirology. 2005;48:372–380. doi: 10.1159/000086064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi K, Katano Y, Honda T, Ishigami M, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, et al. Association of interleukin 28B and mutations in the core and NS5A region of hepatitis C virus with response to peg-interferon and ribavirin therapy. Liver Int. 2011;31:1359–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurosaki M, Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sakamoto N, Enomoto N, Honda M, et al. Pre-treatment prediction of response to pegylated-interferon plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C using genetic polymorphism in IL28B and viral factors. J Hepatol. 2011;54:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saito H, Ito K, Sugiyama M, Matsui T, Aoki Y, Imamura M, et al. Factors responsible for the discrepancy between IL28B polymorphism prediction and the viral response to peginterferon plus ribavirin therapy in Japanese chronic hepatitis C patients. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:958–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda N, Imanishi H, Aizawa N, Tanaka H, Iwata Y, Enomoto H, et al. A nationwide survey in Japan regarding splenectomy/partial splenic embolization for interferon treatment targeting hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease in patients with low platelet count. Hepatol Res. 2013. doi:10.1111/hepr.12184. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Shiffman ML, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sigal S, Bourliere M, et al. Eltrombopag for thrombocytopenia in patients with cirrhosis associated with hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2227–2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chayama K, Hayes CN, Abe H, Miki D, Ochi H, Karino Y, et al. IL28B but not ITPA polymorphism is predictive of response to pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir triple therapy in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:84–93. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrew J. Muir, Mitchell L. Shiffman, Zaman A, Yoffe B, de la Torre A, Flamm S, et al. Phase 1b study of pegylated interferon lambda 1 with or without ribavirin in patients with chronic genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2010;52:822–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Chayama K, Takahashi S, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ikeda K, Ishikawa H, et al. Dual therapy with the nonstructural Protein 5A Inhibitor, BMS-790052, and the Nonstructural Protein 3 Protease Inhibitor, BMS-650032, in Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1b-Infected Null Responders. Hepatology. 2012;55:742–748. doi: 10.1002/hep.24724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]