Abstract

AIM: To assess the hypercoagulability in PBC and its relationship with homocysteine (HCY) and various components of the haemostatic system.

METHODS: We investigated 51 PBC patients (43F/8M; mean age: 63 ± 13.9 yr ) and 102 healthy subjects (86 women/16 men; 63 ± 13 yr), and evaluated the haemostatic process in whole blood by the Sonoclot analysis and the platelet function by PFA-100 device. We then measured HCY (fasting and after methionine loading), tissue factor (TF), thrombin-antithrombin complexes (TAT), D-dimer (D-D), thrombomodulin (TM), folic acid, vitamin B6 and B12 plasma levels. C677T 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphism was analyzed.

RESULTS: Sonoclot RATE values of patients were significantly (P < 0.001) higher than those of controls. Sonoclot time to peak values and PFA-100 closure times were comparable in patients and controls. TAT, TF and HCY levels, both in the fasting and post-methionine loading, were significantly (P < 0.001) higher in patients than in controls. Vitamin deficiencies were detected in 45/51 patients (88.2%). The prevalence of the homozygous TT677 MTHFR genotype was significantly higher in patients (31.4%) than in controls (17.5%) (P < 0.05). Sonoclot RATE values correlated significantly with HCY levels and TF.

CONCLUSION: In PBC, hyper-HCY is related to hypovitaminosis and genetic predisposing factors. Increased TF and HCY levels and signs of endothelial activation are associated with hypercoagulability and may have an important role in blood clotting activation.

Keywords: Homocysteinemia, Hypercoagulability, Primary biliary cirrhosis, Tissue factor, Folic acid

INTRODUCTION

Primary biliary cirrhosis is deemed to be an autoimmune chronic cholestatic disorder of the liver that primarily affects middle aged women. Currently, the diagnosis of PBC is often made when the patient is still asymptomatic, with abnormal liver biochemistry and/or antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA). The symptomatic patients may have fatigue, generalized pruritus, osteoporosis, fat soluble vitamin deficiencies and portal hypertension[1,2]. The disease generally progresses slowly but survival is less than age- and gender-matched general population and natural history may vary greatly from patient to another[3].

Thrombosis of portal veins has been detected in 40% of PBC livers resected at orthotopic liver transplantation (OLTx) and is correlated with history of bleeding varices[4]. It has been hypothesized that portal veins thrombosis may be responsible for causing development of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and progression of liver fibrosis[5,6]. A higher incidence of thrombosis of portal venous tree may be promoted by a hypercoagulable state[7] and recent evidence has demonstrated that PBC patients were hypercoagulable on thromboelastography[8,9]. Scarce data are available on the possible causes of this hypercoagulability. In particular, plasma coagulation factors have not been completely evaluated in these patients.

Hyperhomocysteinemia has been found to be associated with a hypercoagulable state and liver fibrosis[10,11]. It has been documented that mean basal and post-methionine load serum HCY levels are significantly higher in patients with PBC than healthy controls[12]. However these findings need to be confirmed and no data are available on the genetic and acquired causes of such hyperhomocysteinemia and its relationship with hypercoagulability in patients with PBC.

The aim of this study was to investigate basal and post-methionine load serum homocysteine levels, various components of plasmatic coagulation, platelet function and their relationship with hypercoagulability in PBC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Fifty-one consecutive patients with a diagnosis of PBC (43 women and 8 men; age: median 63 ± 13.9 yr (range 20-76) referred to the Gastroenterology Unit of the University of Florence from December 2001 to July 2002, were enrolled. We divided the patients into four staging severity groups: 12 patients in stage I, 11 in stage II, 15 in stage III and 13 in stage IV. Exclusion criteria were renal insufficiency, consumption of alcohol, therapy with steroids, anticoagulants, NSAIDs or methotrexate, folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation. All patients were stable with no history of bleeding or infectious complications at least 6 wk before evaluation. Routine laboratory investigations included aPTT, PT, fibrinogen, liver function tests (bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, aspartate and alanine transaminases), creatinine, cholesterol, iron, calcium, and antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA). All cholestatic patients received vitamin K. All patients had a screening for thyroid-associated disease and intestinal bowel diseases.

One hundred and two healthy subjects with no previous history of liver disease, comparable for age and sex (86 women and 16 men; median 63 ± 13 (range 18-75) yr), recruited from blood donors of our hospital and laboratory volunteers, were used as control group. Patients and controls gave their informed consent to use part of their blood samples for an experimental study.

Experimental procedures

Venous blood samples were collected from the basilical vein after discarding the first 2 mL of blood. We determined HCY plasma levels in the fasting state and 4 h after an oral load with methionine. One hundred mg/Kg of body weight of L-methionine was administered in approximately 200 mL of fruit juice immediately after the fasting phlebotomy.

SonoclotTM analysis

The haemostatic process in whole blood has been measured by the SonoclotTM (Sienco Company, Morrison, CO) analysis, a viscoelastic test on whole blood collected in tubes containing 0.129 M sodium citrate. (Saleem 83) Sonoclot analysis was performed within 30 min from the phlebotomy, with 360 μL citrated blood recalcified with 15 μL of calcium chloride (0.25 mol/L). The following variables were analyzed: (1) the clot RATE, i.e. the gradient of the primary slope measured as Clot Signal Units per minute which is an index of clot formation affected by both platelets and coagulation proteins; (2) the time to peak amplitude (TP) (minutes) which reflects the clot retraction away from the surface of the probe and is mainly influenced by the platelet function.

Platelet function analysis

Platelet function was evaluated by the PFA-100 ® device (Dade-Behring) on whole blood collected in tubes containing 0.129 M sodium citrate. The closure times (CT) were determined on duplicate samples (0.8 mL) within 2 hours of collection, using cartridges containing collagen-coated membranes with epinephrine (Col/Epi cartridge) or ADP (Col/ADP cartridge) as previously described[9].

Blood coagulation parameters

D-dimer (D-D), thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT), tissue factor (TF) and thrombomodulin (TM) plasma levels were evaluated using ELISA method (D-D: Agen, Brisbane, Australia; TAT: Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany; TF: American Diagnostica, Greenwich,CT,USA; TM: Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres, France) on blood samples collected in tubes containing 0.129 M sodium citrate, immediately centrifugated at 4 °C and stored in plasma aliquots at -80 °C and assayed within two weeks.

Homocysteine assay

To determine HCY, whole blood was collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminotetracetate (EDTA) 0.17 mol/L, immediately put in ice and centrifuged within 30 minutes at 4 °C (15 000 x g for 15 min). The supernatant was stored in aliquots at -80 °C until assay. Homocysteine plasma levels were detected by FPIA method (Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany).

Vitamin pattern

Serum folic acid and vitamin B12 were measured by radioassay (ICN Pharmaceuticals, NY)). Serum vitamin B6 was measured with HPLC method and fluorescence detecting (Immundiagnostik, Benheim, Germany).

MTHFR polymorphism

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes. C677T polymorphism in the MTHFR gene was carried out on genomic DNA by PCR amplification as already described[13].

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with SPSS 10.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for unpaired data was used for comparisons between single groups. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (for non-parametric data) was used for the correlation analysis. Fasting and post-methionine hyperhomocysteinemia were defined based on the 95th percentile cut-off of the control population (Fasting: M = 15 μmol/L, F = 13 μmol/L; Post-methionine: M = 38 μmol/L, F = 35 μmol/L).

For genetic analysis, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed using χ2 analysis. All probability values are two-tailed with values less than 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Laboratory characteristics of patients investigated according to the stage of disease are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory characteristics of patients investigated according to the stage of disease1

| Stage | I | II | III | IV |

| Patients (n°) | 12 | 11 | 15 | 13 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L | 273 (50-797) | 447 (145-1315) | 397 (190-1956) | 289 (52-1960) |

| AST (U/L) | 28 (13-6) | 38 (25-400) | 35 (14-63) | 49 (11-144) |

| ALT (U/L) | 37 (14-89) | 54 (17-100) | 39 (17-72) | 47 (8-218) |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.4-2.4) | 0.9 (0.2-1.2) | 0.9 (0.3-1.5) | 1.0 (0.5-1.6) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190 (112-235) | 220 (104-285) | 219 (110-275) | 208 (154-314) |

| aPTT (sec) | 32 (27-63) | 28 (26-43) | 32 (25-37) | 32 (26-36) |

| PT (%) | 98 (90-105) | 100 (91-120) | 99 (81-100) | 93 (58-100) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 379 (279-650) | 380 (268-463) | 327 (276-590) | 380 (100-586) |

1Data are expressed as median (range).

Blood Coagulation and Platelet Analysis

Sonoclot RATE values of PBC patients were significantly higher than those of controls (P < 0.001). In both the 29/51 (57%) PBC patients with a platelet count in normal range and the 22/51 (43%) PBC patients with thrombocytopenia as well as 26/51 (51%) PBC patients, the Sonoclot RATE value was higher than 95% of controls (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Platelet and blood coagulation tests

| PBC patients n = 51 | Controls n = 102 | |

| Sonoclot RATE (U/min) all pts | 29 (14-49)b | 21 (14-31) |

| • <150 x 103/μL plts (n = 22) | 30 (14-49)b | |

| • ≥150 x 103/μL plts (n = 29) | 28 (19-41)d | |

| Sonoclot TP (min) all pts | 12 (6-30)d | 9 (6-15) |

| • <150 x 103/μL plts (n = 22) | 15 (6-30)d | |

| • ≥150 x 103/μL plts (n = 29) | 10 (6-24) | |

| PFA/EPI - CT (secs) | 151.5 (60-222) | 146 (111-179) |

| [≥150 x 103/μL plts (n = 29)] | ||

| PFA/ADP- CT (secs) | 106 (61-180) | 102 (61-148) |

| [≥150 x 103/μL plts (n = 29)] | ||

| TAT (μg/L) | 2.8 (1.5-87.3)b | 2.5 (1.1-4.2) |

| D-Dimer (ng/mL) | 16.0 (2-173) | 23.0 (3-55) |

| TF (pg/mL) | 255.6 (24.8-466.1)d | 121.9 (24.8-466.1) |

| TM (μg/mL) | 23.7 (2.6-153.5)d | 13.8 (7.6-23.1) |

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 vs Controls; TP = time to peak; PFA/EPI - CT = closure time with epinephrine; PFA/ADP-CT = closure time with ADP. Data are expressed as median (range).

Sonoclot TP values were significantly higher only in PBC patients with thrombocytopenia. Indeed, a significant difference of Sonoclot TP (P < 0.001) values was observed between PBC patients with a normal platelet count and with thrombocytopenia (Table 2). The hypercoagulable state and the increased TF circulating levels were independent of the disease’s stage, and were presented even in the first stage of the disease (data not shown).

PFA-100 closure times after stimulation with epinephrine or ADP were comparable in patients with PBC and controls (Table 2). In 9/51 (17.6%) PBC patients, D-dimer plasma levels were higher than 95% of controls but the difference did not reach the statistical significance (P = 0.16).

TAT, thrombomodulin and tissue factor levels were significantly higher in patients than in controls (TAT 2.8 ± 13.9 (1.5-87.3) μg/L vs 2.5 ± 0.52 (1.1-4.2) μg/L; TM 23.7 ± 3.5, (2.6-153.5) ng/mL vs 13.8 ± 4.4 (7.6-23.1) ng/mL; TF 255.6 ± 223.0 (81.4-1259.6) pg/mL vs 121.9 ± 81.9 (24.8- 466.1) pg/mL; P < 0.001).

Homocysteine

HCY plasma levels, both in the fasting state and post-methionine loading, were significantly higher in patients than in controls (Fasting: 12.1 ± 8.76 (1.5-58.8) μmol/L vs 9.9 ± 1.7 (6.4-18.0) μmol/L; Post-methionine 30.1 ± 14.4 (9.2-99.6) μmol/L vs 28.0 ± 5.23 (16.4-38.9) μmol/L, P < 0.001) (Table 3). Totally, hyperhomocysteinemia (defined as a concentration of fasting and/or post-methionine HCY above 95% of controls) was diagnosed in 23/51 patients (45.1%) (8 only fasting; 4 only PM; 11 both). No significant difference in plasma HCY levels was detected between four staging severity groups.

Table 3.

Homocysteine and vitamin levels in PBC patients and controls

| PBC Patients (n = 51) | Controls (n =102) | |

| Fasting HCY (μmol/L) | 12.1 (1.8-58.8)b | 9.9 (6.4-18.0) |

| Post-methionine HCY (μmol/L) | 30.1 (9.2-99.6)b | 28.0(16.4-38.9) |

| Folic Acid (ng/mL) | 5.3(1.2-13.4)b | 10.7(5.4-18.5) |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL | 335 (201-977)a | 304.9(176-427.1) |

| Vitamin B6 (pg/mL) | 6.6 (1-20)b | 10.0 (3-17) |

P < 0.05 vs controls;

P < 0.001 vs control.

Folic acid, vitamins B12 and B6

Vitamin deficiencies (defined as a vitamin concentration below the 10th percentile of controls) were detected in 45/51 patients (88.2%).

Deficiency of folate (defined as a concentration less than 6.4 ng/mL) was documented in 39/51 (76.5%); deficiency of vitamin B12 (defined as a concentration less than 243.7 pg/mL) was found in 6/51 patients (11.8%). Deficiency of vitamin B6 (defined as a concentration less than 3.4 pg/mL) was found in 3/51 patients (5.8%). Three patients had low levels of both folic acid and vitamin B12, 1 patient of both vitamin B12 and B6 and 2 patients of both folic acid and vitamin B6.

Vitamins median values are shown in Table 3.

MTHFR C677T polymorphism

The allele frequency of the C677T polymorphism was 0.52 in patients and 0.45 in controls. The distribution of the three genotypes in controls was as follows: TT 17.5 %; CT 55.3%; CC 27.2%. The genotype distribution in patients was as following: TT 31.4%; CT 41.2%; CC 27.4%. The prevalence of the homozygous TT677 genotype was significantly higher in patients (31.4%) than in controls (17.5%) (P < 0.05).

Patients with the homozygous TT677 genotype had higher, but not statistically significant HCY levels than those with C677T and CC677 genotypes (TT = 13.3 ( 1.8-58.8) μmol/L; CT = 12.3 (7.9-42.6) μmol/L; CC = 10.2 (6.0-21.7) μmol/L).

TTMTHFR polymorphism and/or vitamin deficiencies were present in all hyperhomocysteinemic patients (Table 4). In other words, in patients with normal folic acid plasma levels homocysteinemia was normal except for two patients with TTMTHFR polymorphism.

Table 4.

TTMTHFR polymorphism and vitamin state in 51 PBC patients n (%)

| MMTHFR | Low folate, normal HCY | Normal folate, high HCY | Low folate, high HCY | Normal folate, normal HCY | Total No patients |

| CT | 8 (38) | 0 | 10 (47.6) | 3 (14.45) | 21 |

| CC | 8 (57) | 0 | 2 (14.5) | 4 (28.5) | 14 |

| TT | 3 (18.7) | 2 (12.5) | 9 (56) | 2 (12.5) | 16 |

| Total | 19 | 2 | 21 | 9 |

Correlation between the parameters investigated

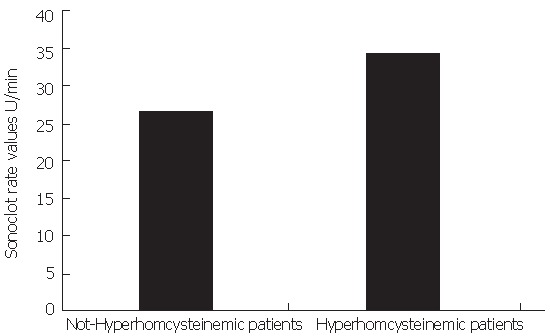

A significant correlation between Sonoclot rate values, TAT (r = 0.44, P < 0.001), TF plasma levels (r = 0.30, P < 0.05) and basal HCY (r = 0.45, P < 0.001) was observed. Sonoclot rate was significantly higher in patients with high fasting state and/or post-methionine than in the other patients [34 ± 7.4 (22-45) U/min vs 26 ± 5.4 (14-49) U/min (Figure 1)]. Moreover, a significant correlation was detected between HCY, TM (r = 0.54, P < 0.001) and TF (r = 0.55, P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Sonoclot rate values in PBC patients with or without hyperhomocysteinemia.

TAT levels correlated significantly with TF (r = 0.43, P < 0.05) while HCY plasma levels correlated significantly with cholesterol plasma levels (r = 0.55, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Hypercoagulability in PBC has been previously documented with thromboelastography[8,9], and here we have confirmed this finding with Sonoclot, another technique of analysis of haemostatic process, and demonstrated high TAT circulating levels in 51 PBC patients.

Hypercoagulability may have two different roles in natural history of PBC: it could promote portal veins thrombosis and liver damage and on the other hand it could be responsible for a more favourable prognosis of variceal bleeding[14,15] and a lower blood loss at liver transplantation[11,16-19]. It has been hypothesized that portal veins thrombosis may be responsible for causing development of regenerative nodules and non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and progression of liver fibrosis[5,6]. In PBC patients hypercoagulability may contribute to the high incidence of oesophageal varices in early histological stages associated with the presence of regenerating nodules[20]. A recent study demonstrated that anticoagulant therapy with a thrombin antagonism can reduce fibrogenesis in rat liver[21], it could be interesting to evaluate if a correction of hypercoagulability could reduce the intrahepatic thrombosis formation and development of liver fibrosis and portal hypertension.

Moreover we found that TF might be involved in determination of thrombophilic status, in fact TF levels are higher in PBC patients than in healthy controls and are related to Sonoclot Rate values. TF is a glycoprotein present on the surface of the plasma membranes of monocytes, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells[22,23], and it is the primary cellular trigger of the coagulation cascade. In our patients clinical conditions that may affect TF concentrations such as infections, neoplasia, or heparin administration have been ruled out. Lymphocyte activation is able to induce tissue factor expression by monocytes[23]. PBC is characterized by an intense biliary and systemic inflammatory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response[23,25] and may be responsible for tissue factor expression and subsequent elevation of circulating levels.

Our data confirm the finding of elevated homocysteine levels in patients with PBC. Hyperhomocysteinemia has been found to be associated with a hypercoagulable state and liver fibrosis[10]. Here we demonstrated that HCY levels are associated with hypercoagulability and, as reported by others in the setting of thrombotic diseases[26,27], in this study we offer the “in vivo” demonstration that in PBC patients high levels of HCY are related to increased TF plasma concentration. TF expression by endothelial cells and monocyte-macrophages may be induced by HCY. This effect has been documented in vitro studies, in experimental animals and in hyperhomocysteinemic patients in a specific and dose-dependent manner[28]. HCY may be one of the mechanisms involved in the endothelial stimulation, as documented by the significant correlation with TM levels, which are significantly higher in patients than in controls.

Platelet function has been investigated by two parameters: Sonoclot TP value and PFA-100 closure time. Both of them have been found to be comparable or even higher than healthy controls values. These data are similar to those presented by Pihush et al[9].

As regards fibrinolysis, our data demonstrate that the hypercoagulable state in PBC patients is not associated with a comparable activation of fibrinolysis, as no difference in D-D levels was documented between patients and controls. Further studies are necessary to thoroughly investigate fibrinolysis, and in particular its main inhibitor, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which may be released by stimulated monocytes and endothelial cells[29]. This behaviour of fibrinolytic system may contribute to determine a prothrombotic state.

In this study the main possible genetic and acquired alterations of HCY metabolism in PBC were investigated. We demonstrated the presence of vitamin deficiencies related to methionine metabolism (folic acid, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12) in about 90% of patients. In particular, the majority of patients had a folate deficiency. This is a novel finding that arises from the question about the potential clinical utility of a low-cost vitamin supplementation in these patients. It should be investigated if folate supplementation could correct hyperhomocysteinemia and/or hypercoagulability. Folate levels may be low due to inadequate dietary intake, malabsorption, increased utilization or to effects of drugs[30]; in our patients we excluded the presence of drugs able to interfere with folate absorption, such as methotrexate. Disease activity may contribute to increased demand for folate due to inflammation[32]. However, we found no correlation between disease activity, as measured by histological stage, and folate or HCY levels. Therefore, these data may point to inadequate intake as a significant factor that affects folate levels. Another hypothesis is the presence of an impairment of the folate enterohepatic circulation. This cycle plays an important role in the homeostasis of folic acid. It has been demonstrated that the interruption of bile circulation by bile drainage leads, to a rapid fall in serum folate levels to 30% of base line within 4-6 h[33]. Cholestasis could make this system of vitamin reutilization ineffective, and could induce folate low serum levels.

No data are available on the prevalence of C677T 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphism in PBC patients. This polymorphism is one of the most frequent genetic factors responsible for the alteration of HCY levels, especially in the presence of a suboptimal folate status[34,35]. We found a significant higher prevalence of the homozygous TT677 genotype in PBC patients. In these patients MTHFR has a reduced activity caused by a C-T substitution at nucleotide 677[36]. However, in order to investigate the prevalence of this genetic polymorphism in PBC further larger studies are needed.

In PBC serum cholesterol levels markedly increase with worsening of cholestasis[37,38]. In this study, as in others,[39,40] a significant in vivo association between HCY and cholesterol circulating levels was found, suggesting another possible explanation, together with cholestasis, for hypercholesterolemia in this disease.

Recently, in cultured human hepatocytes it was demonstrated that hyperhomocysteinemia determines an oxidative stress of the endoplasmic reticulum which activates the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs)[41]. The activation of SREBPs is associated with increased expression of genes responsible for cholesterol/triglyceride biosynthesis, and may be an explanation to our findings.

In conclusion, hypercoagulability and hyperhomocysteinemia exist in patients with PBC, and there is an association between these two parameters. TF may have a role in determination of blood clotting activation and hyperhomocysteinemia is related to hypovitaminosis and genetic predisposing factors. Further studies are needed to clarify if hyperhomocysteinemia and hypercoagulability may have a role in progression of liver damage and if they may be influenced by vitamin supplementation.

Footnotes

Co-first-author: Biagini Maria Rosa

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhang JZ E- Editor Bi L

References

- 1.Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2003;362:53–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13808-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan MM. Primary biliary cirrhosis: past, present, and future. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1392–1394. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metcalf JV, Mitchison HC, Palmer JM, Jones DE, Bassendine MF, James OF. Natural history of early primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 1996;348:1399–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shannon P, Wanless IR. Hepatology. 1995:22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wanless IR, Wong F, Blendis LM, Greig P, Heathcote EJ, Levy G. Hepatic and portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: possible role in development of parenchymal extinction and portal hypertension. Hepatology. 1995;21:1238–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanless IR, Liu JJ, Butany J. Role of thrombosis in the pathogenesis of congestive hepatic fibrosis (cardiac cirrhosis) Hepatology. 1995;21:1232–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papatheodoridis GV, Papakonstantinou E, Andrioti E, Cholongitas E, Petraki K, Kontopoulou I, Hadziyannis SJ. Thrombotic risk factors and extent of liver fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis. Gut. 2003;52:404–409. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.3.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Ari Z, Panagou M, Patch D, Bates S, Osman E, Pasi J, Burroughs A. Hypercoagulability in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis evaluated by thrombelastography. J Hepatol. 1997;26:554–559. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pihusch R, Rank A, Gohring P, Pihusch M, Hiller E, Beuers U. Platelet function rather than plasmatic coagulation explains hypercoagulable state in cholestatic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2002;37:548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Tevijano ER, Berasain C, Rodríguez JA, Corrales FJ, Arias R, Martín-Duce A, Caballería J, Mato JM, Avila MA. Hyperhomocysteinemia in liver cirrhosis: mechanisms and role in vascular and hepatic fibrosis. Hypertension. 2001;38:1217–1221. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.099499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coppola A, Davi G, De Stefano V, Mancini FP, Cerbone AM, Di Minno G. Homocysteine, coagulation, platelet function, and thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2000;26:243–254. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Ari Z, Tur-Kaspa R, Schafer Z, Baruch Y, Sulkes J, Atzmon O, Greenberg A, Levi N, Fainaru M. Basal and post-methionine serum homocysteine and lipoprotein abnormalities in patients with chronic liver disease. J Investig Med. 2001;49:325–329. doi: 10.2310/6650.2001.33897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbate R, Sardi I, Pepe G, Marcucci R, Brunelli T, Prisco D, Fatini C, Capanni M, Simonetti I, Gensini GF. The high prevalence of thermolabile 5-10 methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) in Italians is not associated to an increased risk for coronary artery disease (CAD) Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gores GJ, Wiesner RH, Dickson ER, Zinsmeister AR, Jorgensen RA, Langworthy A. Prospective evaluation of esophageal varices in primary biliary cirrhosis: development, natural history, and influence on survival. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1552–1559. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biagini MR, Guardascione M, McCormick AP, Raskino C, McIntyre N, Burroughs AK. Bleeding varices in PBC and its prognostic significance. Gut. 1990:A1209. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popov VN. [New findings concerning the helminth fauna of striped seals inhabiting the southern part of the sea of okhotsk] Parazitologiia. 1975:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritter DM, Owen CA Jr, Bowie EJ, Rettke SR, Cole TL, Taswell HF, Ilstrup DM, Wiesner RH, Krom RA. Evaluation of preoperative hematology-coagulation screening in liver transplantation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:216–223. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallett SV, Cox DJ. Thrombelastography. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:307–313. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palareti G, Legnani C, Maccaferri M, Gozzetti G, Mazziotti A, Martinelli G, Zanello M, Sama C, Coccheri S. Coagulation and fibrinolysis in orthotopic liver transplantation: role of the recipient's disease and use of antithrombin III concentrates. S. Orsola Working Group on Liver Transplantation. Haemostasis. 1991;21:68–76. doi: 10.1159/000216206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kew MC, Varma RR, Dos Santos HA, Scheuer PJ, Sherlock S. Portal hypertension in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 1971;12:830–834. doi: 10.1136/gut.12.10.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duplantier JG, Dubuisson L, Senant N, Freyburger G, Laurendeau I, Herbert JM, Desmoulière A, Rosenbaum J. A role for thrombin in liver fibrosis. Gut. 2004;53:1682–1687. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.032136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemerson Y. Tissue factor: then and now. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jude B, Fontaine P. Modifications of monocyte procoagulant activity in diabetes mellitus. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1991;17:445–447. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akbar SM, Yamamoto K, Miyakawa H, Ninomiya T, Abe M, Hiasa Y, Masumoto T, Horiike N, Onji M. Peripheral blood T-cell responses to pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in primary biliary cirrhosis: role of antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:639–646. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kita H, Lian ZX, Van de Water J, He XS, Matsumura S, Kaplan M, Luketic V, Coppel RL, Ansari AA, Gershwin ME. Identification of HLA-A2-restricted CD8(+) cytotoxic T cell responses in primary biliary cirrhosis: T cell activation is augmented by immune complexes cross-presented by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:113–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egerton W, Silberberg J, Crooks R, Ray C, Xie L, Dudman N. Serial measures of plasma homocyst(e)ine after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:759–761 [. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindgren A, Brattström L, Norrving B, Hultberg B, Andersson A, Johansson BB. Plasma homocysteine in the acute and convalescent phases after stroke. Stroke. 1995;26:795–800. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colli S, Eligini S, Lalli M, Camera M, Paoletti R, Tremoli E. Vastatins inhibit tissue factor in cultured human macrophages. A novel mechanism of protection against atherothrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:265–272. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irigoyen JP, Muñoz-Cánoves P, Montero L, Koziczak M, Nagamine Y. The plasminogen activator system: biology and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:104–132. doi: 10.1007/PL00000615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanger O. Physiology of folic acid in health and disease. Curr Drug Metab. 2002;3:211–223. doi: 10.2174/1389200024605163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elsborg L, Larsen L. Folate deficiency in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1979;14:1019–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franklin JL, Rosenberg HH. Impaired folic acid absorption in inflammatory bowel disease: effects of salicylazosulfapyridine (Azulfidine) Gastroenterology. 1973;64:517–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg SE, Campbell CL, Hillman RS. Effect of alcohol on tumor folate supply. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;31:1461–1463. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, Boers GJ, den Heijer M, Kluijtmans LA, van den Heuvel LP. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10:111–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D'Angelo A, Selhub J. Homocysteine and thrombotic disease. Blood. 1997;90:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang SS, Wong PW, Susmano A, Sora J, Norusis M, Ruggie N. Thermolabile methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase: an inherited risk factor for coronary artery disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:536–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longo M, Crosignani A, Battezzati PM, Squarcia Giussani C, Invernizzi P, Zuin M, Podda M. Hyperlipidaemic state and cardiovascular risk in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 2002;51:265–269. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crippin JS, Lindor KD, Jorgensen R, Kottke BA, Harrison JM, Murtaugh PA, Dickson ER. Hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in primary biliary cirrhosis: what is the risk? Hepatology. 1992;15:858–862. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olszewski AJ, McCully KS. Homocysteine content of lipoproteins in hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 1991;88:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(91)90257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCully KS, Olszewski AJ, Vezeridis MP. Homocysteine and lipid metabolism in atherogenesis: effect of the homocysteine thiolactonyl derivatives, thioretinaco and thioretinamide. Atherosclerosis. 1990;83:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(90)90165-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Werstuck GH, Lentz SR, Dayal S, Hossain GS, Sood SK, Shi YY, Zhou J, Maeda N, Krisans SK, Malinow MR, et al. Homocysteine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress causes dysregulation of the cholesterol and triglyceride biosynthetic pathways. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1263–1273. doi: 10.1172/JCI11596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]