Abstract

A 42-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital because of multiple liver tumors detected by ultrasono-graphy. Colonoscopy revealed submucosal tumor in the rectum, which was considered the primary lesion. Endoscopic mucosal resection followed by histopathological examination revealed that the tumor was carcinoid. The resected margin of the tumor was positive for malignant cells. Two courses to transcatheter arterial chemotherapy for liver metastasis were ineffective. Accordingly, the rectal tumor and metastatic lymph nodes were surgically resected. One month after the operation, she received liver transplantation (left lateral segment and caudate lobe) from her son. No recurrent lesion has been observed at two years after the liver transplantation. Liver transplantation should be considered as a treatment option even in advanced case of carcinoid metastasis to the liver. We also discuss the literature on liver transplantation for metastatic carcinoid tumor.

Keywords: Carcinoid, Liver metastasis, Living related liver transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoid tumors are slow-growing neuroendocrine tumors, and often metastasize to the liver. There is no established treatment for liver metastases and the prognosis is poor[1,2]. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumor has already been reported worldwide[3-16], but the procedure is rarely performed in Japan[17]. We report here a case of living-related liver transplantation for liver metastases of rectal carcinoid tumor.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital because of multiple liver tumors detected by ultrasonography. The medical history included bronchial asthma. There was no history of blood transfusion. Physical examination revealed a hard and swollen liver in the upper abdomen. Laboratory tests showed erythrocyte count of 367 × 104/mm3 (normal: 400-500 × 104/mm3), hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL (11.8-15.1 g/dL), leukocyte count 8200/mm3 (4000-9600/mm3), platelet count 25.9 × 104/mm3 (16.0-35.0 × 104/mm3), serum albumin 4.2 g/dL (3.9-5.0 g/dL), total bilirubin (T-Bil) 1.0 mg/dL (0.3-1.2 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 30 IU/L(13-33 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 39 IU/L (6-27 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 311 IU/L (115-359 IU/L), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ -GTP) 137 IU/L (10-47 IU/L), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 20.0 mg/dL (8.0-20.0 mg/dL), and creatine (Cr) 0.9 mg/dL (0.6-1.0 mg/dL). Hepatitis B surface and hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. Serotonin and 5-HIAA in serum were within the normal range. Carcinoembryonic antigen, CA19-9, alfa-fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K antagonist (PIVKA)-II were normal but neuron-specific enolase (NSE) was elevated 46.1 ng/mL (0-10.0 ng/mL).

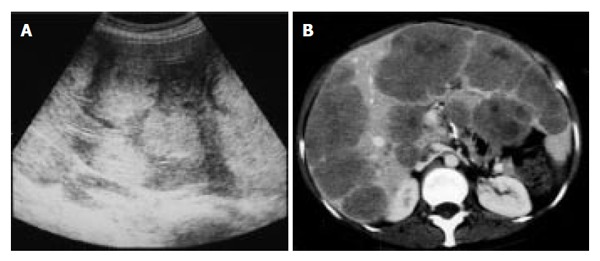

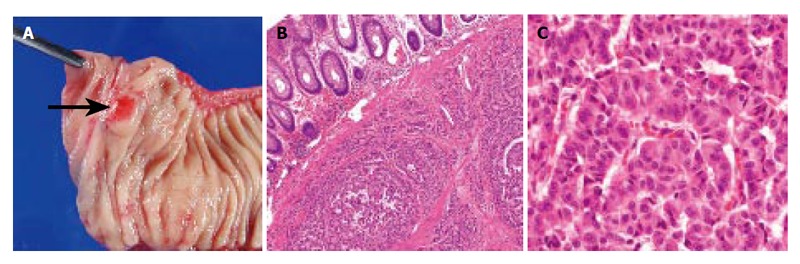

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed multiple hyperechoic masses in both lobes of the liver (Figure 1A). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) also revealed multiple liver tumors enhanced mildly (Figure 1B). Abdominal angiography showed hepatomegaly and multiple liver tumors supplied by the hepatic artery. Colonoscopy showed submucosal tumor in the rectum. This tumor appeared as a low echoic mass by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Then we performed endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for the submucosal tumor of the rectum, which was histopathologically diagnosed as carcinoid tumor. The resected margin of the tumor was positive for malignant cells. Transcatheter arterial chemotherapy for liver metastasis was applied twice (first: 5-fluorouracil [5-FU] + epirubicin [EPI] + mitomycin C [MMC], second: 5-FU + methotrexate [MTX]), but was ineffective because the liver tumors did not decrease in size and even grow 2 mo after the TACE. Accordingly, the rectal tumor and metastatic lymph nodes were resected surgically. Macroscopically, the rectal tumor was an elevated lesion with a central depression, measuring 58 mm in a diameter (Figure 2A). Histopathological examination showed atypical cells forming tubular and alveolar structures, with slightly swollen nuclei (Figures 2B and 2C). Lymph node metastases and blood vessel invasions were detected. Immunohistochemical examination revealed that most tumor cells were stained with chromogranin A, NSE and synaptophysin. The Ki-67 index was 6.1, but p53 protein was negative.

Figure 1.

A: Ultrasonography showed multiple hyperechoic masses in the liver; B: Dynamic computed tomography showed multiple liver tumors. The surfaces of these tumors showed mild enhancement.

Figure 2.

A: Macroscopic findings of the resected rectum. Arrow shows the primary lesion; B: The tumor cells showed tubular and alveolar formation, and their nuclei were slightly swelling (C). (B, C: H&E, original magnification, B: x 40, C: x 400).

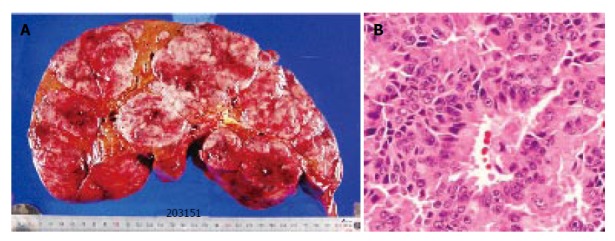

One month after the operation, there were no recurrence except for the liver. She received a liver transplantation (left lateral segment and caudate lobe) from her son. Standard liver volume (SLV) was 1 014.4 g, graft volume (GV) was 450 g, GV/ SLV ratio was 44.4% and graft-to-recipient weight ratio (GR-WR) was 0.98. The volume of the resected liver was 4750 g, and multiple nodules of white and brown colors occupied the whole liver (Figure 3A). The histopathological findings of the liver tumor (Figure 3B) were similar to those of the primary lesion. No invasion of the portal vein, hepatic vein, and bile duct was noted.

Figure 3.

A: The cut surface of the resected specimen showed multiple tumors; B: Histopathological findings of the liver tumor were similar to those of the rectal tumor (H&E, original magnification, x 400).

Her clinical course has been good and no recurrence has been demonstrated two years since the liver transplantation.

DISCUSSION

Neuroendocrine tumors have generally been classified by the site of origin. Furthermore, a new histopathological classification was reported by WHO[18]. The WHO classification has been considered by the size of the tumor, the depth of the tumor invasion, angiogenesis, lymphatic invasion, cellular atypia, necrosis, mitoses, Ki-67 index and p53 protein. Based on this classification, neuroendocrine tumors are divided into three types, well-differentiated endocrine tumor (carcinoid), well-differentiated endocrine carcinoma (malignant carcinoid), and poorly-differentiated endocrine carcinoma (small cell carcinoma)[18]. Although the standard therapy for liver metastasis of neuroendocrine origin is surgical resection[19], the prognosis of neuroendocrine tumor with liver metastasis is usually poor[1,2]. When curative hepatic resection is difficult, transcatheter arterial chemo-embolization (TACE) and intra-arterial chemotherapy are performed and have been reported to be effective[20-23]. Our patient received two courses of intra-arterial chemotherapy but no satisfactory response was observed. Somatostatin analogue and interferon have been used for the treatment of carcinoid tumors[24-27]. These therapies are excellent for improvement of symptoms but the tumor response rate is usually low[24-27].

Liver transplantation has been widely performed in patients with end-stage liver disease and metastatic liver cancers from neuroendocrine tumors[3-6]. The 5-year survival rate of transplant recipients for neuroendocrine tumors metastases to the liver ranges from 0 to 83% (median, 50%) (Table 1). The main cause of death is recurrence of the carcinoid tumors. In Japan, the accumulative

Table 1.

Literature review of liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors

| Reference | Number of patients | Median follow-up (m) |

Survival rate (%) |

Disease-free survival rate (%) |

|||

| 1-yr | 3-yr | 5-yr | 1-yr | 5-yr | |||

| Rosenau et al (2002)[3] | 19 | 38 | 89 | 89 | 80 | 56 | 21 |

| Coppa et al (2001)[4] | 9 | 39 | 100 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 53 |

| Lehnert et al (1998)[5] | 103 | - | 68 | 54 | 47 | 60 | 24 |

| Le Treut et al (1997)[6] | 31 | 25 | 59 | 47 | 36 | 45 | 17 |

| Florman et al (2004)[7] | 11 | 30 | 73 | 48 | 36 | ||

| Cahlin et al (2003)[8] | 10 | 28 | 80 | 80 | - | - | - |

| Olausson et al (2002)[9] | 9 | 22 | 89 | 89 | - | - | - |

| Ringe et al (2001)[10] | 5 | 18 | 80 | 80 | - | - | - |

| Pascher et al (2000)[11] | 4 | 42 | 100 | 75 | 50 | - | - |

| Frilling et al (1998)[12] | 4 | 54 | 50 | 50 | 50 | - | - |

| Lang H et al (1997) [13] | 12 | 49.5 | 83 | 83 | 83 | - | - |

| Dousset et al (1996)[14] | 9 | 29 | 33 | 33 | 33 | - | - |

| Anthuber et al (1996)[15] | 4 | 11 | 25 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Routley et al (1995)[16] | 11 | - | 82 | - | 57 | - | - |

| Japan (2005)[17] | 6 | - | 66.7 | 66.7 | - | - | - |

living related liver transplantations between 1996 and 2002 are more than 2000. Among these, transplantation was performed in only 6 cases of metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (0.2 %) and the 3-year survival rate is 66.7%[17]. Strictly speaking, the 5-year survival rate of liver transplantation for metastatic carcinoid tumor is 69% but is poor in noncarcinoid neuroendocrine tumors (4-year survival rate, 8%)[6]. Thus, histopathological discrimination is very important to predict the prognosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Our patient had a typical carcinoid tumor which is compatible with well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, with metastases in the liver and was considered to show good prognosis after transplantation. However, the case was advanced stage with lymph node metastasis, lymphatic and vascular invasion and extensive liver metastasis, and thus was considered a high recurrent risk requiring careful follow-up. Unexpectedly good prognosis of this case could be related to the radical resection of the tumor including primary and metastatic lesion and not classified in poor prognosis such as non-pancreatic primary lesion (rectum) and noncarcinoid apudoma[6]. The prognosis was markedly improved by transplantation and she remains well 2 years and 9 mo after surgery without local recurrence and metastasis. Although much longer follow-up period would provide more meaningful information to elucidate the prognosis of such unusual case, liver transplantation could be life-saving procedure for patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumor resistant to alternative treatments.

Pelosi et al[28] reported that Ki-67 index is a significant predictor of prognosis and survival of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Furthermore, Moyana

et al[29] reported that MIB-1 and p53 were associated with metastasis of the gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors. Rosenau et al[3] pathologically investigated patients who received a liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. They reported that the survival rate of patients with high Ki-67 index (> 5%) or overexpression of the E-cadherin was low, and suggested that Ki-67 index and E-cadherin expression could be potentially useful prognostic markers after liver transplantation[3]. Our patient showed moderately positive Ki-67 index (6.1%, rate for carcinoid is around 2-3%) and should be followed as high recurrence risk case.

The Japanese medical insurance system covers liver transplantation for liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) based on Milan criteria[30]. However, the system does not cover metastatic liver cancer. Liver transplantation is a kind of special treatment for the end-stage liver disease and is also expensive. So, not all the patient in the end-stage liver disease has been covered by medical insurance in Japan. In our patient, distant and lymph node metastases were completely resected, and metastatic neuroendocrine tumors in the liver were removed through hepatectomy and liver transplantation even though the metastasis was far advanced within the liver though localized in the liver. We propose that metastatic neuroendocrine tumors of the liver should be classified as similar to HCC although cases beyond Milan criteria[30], like our case, could be also included in such classification because of its biological low malignant character.

In conclusion, we reported a female patient who underwent successful living liver transplantation for advanced liver metastases of rectal carcinoid tumor. She has been well for the last two postoperative years and remains alive without any recurrence in spite of positivity of poor prognostic parameters. Other parameters, such as oncogene, suppressor gene and cyclin shown in hepatocellular carcinoma[31], apart from those of histopathology and immunohistochemistry, are needed to help in clinical decision making with respect to the indications of transplantation.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhang JZ E- Editor Liu WF

References

- 1.Soga J. Carcinoids of the rectum: an evaluation of 1271 reported cases. Surg Today. 1997;27:112–119. doi: 10.1007/BF02385898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawes L, Schulte WJ, Condon RE. Carcinoid tumors. Arch Surg. 1984;119:375–378. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390160011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenau J, Bahr MJ, von Wasielewski R, Mengel M, Schmidt HH, Nashan B, Lang H, Klempnauer J, Manns MP, Boeker KH. Ki67, E-cadherin, and p53 as prognostic indicators of long-term outcome after liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Transplantation. 2002;73:386–394. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200202150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coppa J, Pulvirenti A, Schiavo M, Romito R, Collini P, Di Bartolomeo M, Fabbri A, Regalia E, Mazzaferro V. Resection versus transplantation for liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1537–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)02586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehnert T. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: An analysis of 103 patients. Transplantation. 1998;66:1307–1312. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199811270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Treut YP, Delpero JR, Dousset B, Cherqui D, Segol P, Mantion G, Hannoun L, Benhamou G, Launois B, Boillot O, et al. Results of liver transplantation in the treatment of metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. A 31-case French multicentric report. Ann Surg. 1997;225:355–364. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199704000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Florman S, Toure B, Kim L, Gondolesi G, Roayaie S, Krieger N, Fishbein T, Emre S, Miller C, Schwartz M. Liver transplantation for neuroendocrine tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cahlin C, Friman S, Ahlman H, Backman L, Mjornstedt L, Lindner P, Herlenius G, Olausson M. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumor disease. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:809–810. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(03)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olausson M, Friman S, Cahlin C, Nilsson O, Jansson S, Wängberg B, Ahlman H. Indications and results of liver transplantation in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. World J Surg. 2002;26:998–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6631-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ringe B, Lorf T, Dopkens K, Canelo R. Treatment of hepatic metastases from gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: role of liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2001;25:697–699. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascher A, Steinmuller T, Radke C, Hosten N, Wiedenmann B, Neuhaus P, Bechstein WO. Primary and secondary hepatic manifestation of neuroendocrine tumors. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000;385:265–270. doi: 10.1007/s004230000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frilling A, Rogiers X, Malago M, Liedke O, Kaun M, Broelsch CE. Liver transplantation in patients with liver metastases of neuroendocrine tumors. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:3298–3300. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(98)01037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang H, Oldhafer KJ, Weimann A, Schlitt HJ, Scheumann GF, Flemming P, Ringe B, Pichlmayr R. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg. 1997;225:347–354. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dousset B, Saint-Marc O, Pitre J, Soubrane O, Houssin D, Chapuis Y. Metastatic endocrine tumors: medical treatment, surgical resection, or liver transplantation. World J Surg. 1996;20:908–914; discussion 914-5. doi: 10.1007/s002689900138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anthuber M, Jauch KW, Briegel J, Groh J, Schildberg FW. Results of liver transplantation for gastroenteropancreatic tumor metastases. World J Surg. 1996;20:73–76. doi: 10.1007/s002689900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Routley D, Ramage JK, McPeake J, Tan KC, Williams R. Orthotopic liver transplantation in the treatment of metastatic neuroendocrine tumors of the liver. Liver Transpl Surg. 1995;1:118–121. doi: 10.1002/lt.500010209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Japanese Liver Transplantation Society. Liver transplantation in Japan -Registry by the Japanese Liver Transplantation Society- Jap J Transplantation. 2005;39:634–642. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishikura K, Watanabe H, Iwafuchi M, Ajioka Y, Mukai G. [Diagnosis and treatment of carcinoid tumors in the gastrointestinal tract] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2003;30:606–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loftus JP, van Heerden JA. Surgical management of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors. Adv Surg. 1995;28:317–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajarizadeh H, Ivancev K, Mueller CR, Fletcher WS, Woltering EA. Effective palliative treatment of metastatic carcinoid tumors with intra-arterial chemotherapy/chemoembolization combined with octreotide acetate. Am J Surg. 1992;163:479–483. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(92)90392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drougas JG, Anthony LB, Blair TK, Lopez RR, Wright JK Jr, Chapman WC, Webb L, Mazer M, Meranze S, Pinson CW. Hepatic artery chemoembolization for management of patients with advanced metastatic carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg. 1998;175:408–412. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therasse E, Breittmayer F, Roche A, De Baere T, Indushekar S, Ducreux M, Lasser P, Elias D, Rougier P. Transcatheter chemoembolization of progressive carcinoid liver metastasis. Radiology. 1993;189:541–547. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.2.7692465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roche A, Girish BV, de Baère T, Baudin E, Boige V, Elias D, Lasser P, Schlumberger M, Ducreux M. Trans-catheter arterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for hepatic metastases from endocrine tumors. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:136–140. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oberg K, Norheim I, Theodorsson E. Treatment of malignant midgut carcinoid tumours with a long-acting somatostatin analogue octreotide. Acta Oncol. 1991;30:503–507. doi: 10.3109/02841869109092409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janson ET, Oberg K. Long-term management of the carcinoid syndrome. Treatment with octreotide alone and in combination with alpha-interferon. Acta Oncol. 1993;32:225–229. doi: 10.3109/02841869309083916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold R, Trautmann ME, Creutzfeldt W, Benning R, Benning M, Neuhaus C, Jurgensen R, Stein K, Schafer H, Bruns C, et al. Somatostatin analogue octreotide and inhibition of tumour growth in metastatic endocrine gastroenteropancreatic tumours. Gut. 1996;38:430–438. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oberg K, Eriksson B. The role of interferons in the management of carcinoid tumors. Acta Oncol. 1991;30:519–522. doi: 10.3109/02841869109092411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelosi G, Bresaola E, Bogina G, Pasini F, Rodella S, Castelli P, Iacono C, Serio G, Zamboni G. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas: Ki-67 immunoreactivity on paraffin sections is an independent predictor for malignancy: A comparative study with proliferating-cell nuclear antigen and progesterone receptor protein immunostaining, mitotic index, and other clinicopathologic variables. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1124–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(96)90303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moyana TN, Xiang J, Senthilselvan A, Kulaga A. The spectrum of neuroendocrine differentiation among gastrointestinal carcinoids: importance of histologic grading, MIB-1, p53, and bcl-2 immunoreactivity. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:570–576. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0570-TSONDA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh JW, Finkelstein SD, Demetris AJ, Swalsky PA, Sasatomi E, Bandos A, Subotin M, Dvorchik I. Genotyping of hepatocellular carcinoma in liver transplant recipients adds predictive power for determining recurrence-free survival. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:664–671. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]