Abstract

AIM: To investigate the correlation of depressed-type (0-IIc) colorectal neoplasm and family history of first-degree relatives (FDR) with colorectal cancer (CRC).

METHODS: This cross-sectional study was conducted from June 2000 to October 2002 at National Cancer Center Hospital East. Eligible patients undergoing initial total colonoscopy were surveyed regarding family history of CRC among FDR by a questionnaire prior to colonoscopic examinations. All endoscopic findings during colonoscopy were recorded and the macroscopic classification of the early stage neoplasm/cancer was classified into two types (0-IIc vs non 0-IIc). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression to estimate the association between macroscopic features and clinicopathological data including gender, age, and family history of FDR with CRC.

RESULTS: The OR of an association between family history of FDR with CRC and overall early stage neoplasm adjusted by gender and age was 1.85 (95% CI: 1.31-2.61, P = 0.0004), that for non 0-IIc neoplasm was 1.71 (95% CI: 1.22-2.41, P = 0.0017) and for 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm was 2.78 (95% CI: 1.49-5.16, P = 0.0031).

CONCLUSION: Our study shows a significant association between a family history of FDR with CRC and 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm. When patients with a family history of FDR with CRC undergo colonoscopy, colonoscopists should check carefully for not only polypoid, but also depressed-type (0-IIc) lesions.

Keywords: Depressed-type, Family history, Colorectal cancer, First-degree relative, Colonoscopy

INTRODUCTION

In Japan, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most important cause of cancer mortality and the incidence of CRC is increasing gradually[1]. The prognosis for patients with CRC is strictly dependent on early detection of premalignant and malignant lesions. Familial risk management is one of the important strategies for CRC prevention. There is evidence from cohort and case-control studies that people with close relatives with CRC have an increased risk of CRC and develop the disease at a younger age than those without a family history of CRC[2-4]. In clinical guidelines and rationale for CRC screening and surveillance in USA, approximate lifetime risk of CRC, when a first-degree relative (FDR) was affected with large bowel malignancy, was found to increase by 2-3 fold[5]. In addition, there is a report that a family history of CRC is a strong risk factor for adenoma growth[6,7].

However, previous studies concerning familial risk for CRC did not investigate the data from the perspective of macroscopic classifications of colorectal neoplasm. As the Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the colon proposed, special attention is attached to depressed-type (0-IIc) lesions. Even when the diameter is small, 0-IIc lesions are often at a more advanced stage of neoplasia, with deeper invasion than other types of lesion[8,9]. However, to our knowledge, whether the risk of 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm is correlated with family history of FDR with CRC has not been investigated previously. In this study, we therefore investigated the correlation of 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm and family history of FDR with CRC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility and exclusion criteria

Between June 2000 and October 2002, all patients undergoing initial total colonoscopy at National Cancer Center Hospital East were screened for eligibility for this study. The exclusion criteria were age < 50 years old, past history of surgical resection for CRC, past history of endoscopic treatment for colorectal neoplasm, family history of familial adenomatous polyposis or hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, past history of inflammatory bowel disease and presence of either submucosal tumor, metastatic colorectal tumor or ischemic colitis. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Questionnaire of family history and past history

All patients had been asked for family history of CRC among FDR of patients by a questionnaire prior to colonoscopic examinations. Colonoscopists were kept unaware of this information until the end of the examinations.

Total colonoscopy

A preparatory solution of electrolytes and polyethylene glycol was administered orally to each patient. An anti-cholinergic agent was administered intramuscularly before each examination to prevent persistent colonic spasms, if there was no contraindication to its use. Total colonoscopies were performed using magnifying colonoscopes (CF200Z, CF240Z; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). All detected lesions were diagnosed by magnifying colonoscopy using a non-biopsy technique to differentiate between hyperplastic polyps and adenomas[10,11]. When any neoplasm was suspected, 0.2% indigo carmine dye was sprayed on the area to highlight the lesions. All detected lesions were finally diagnosed by magnification with chromoendoscopy, and the lesions diagnosed as neoplasm were removed or biopsied to evaluate the histological findings. Lesions, diagnosed as hyperplastic polyps macroscopically or histologically, were excluded from this analysis.

Histological and macroscopic evaluation

Histological diagnoses were based on the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO)[12]. Intramucosal neoplasms, including intramucosal carcinoma and submucosal cancer that had spread through the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa, were defined as early stage neoplasm/cancer. Malignant lesions involving the muscularis propria or beyond on histological examination were classified as advanced cancer.

All endoscopic findings during colonoscopy were recorded at each examination. The macroscopic classification of early stage neoplasm/cancer was classified into two types (0-IIc vs non 0-IIc) using the system proposed by the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum[13], which is nearly similar to the Paris endoscopic classification proposed in 2003[8]. In this study, type 0-IIc lesions included the combined type (0-IIc+IIa, 0-IIa+IIc, 0-Is+IIc)[9] and laterally spreading flat-type tumor[14,15]; so called “LST non-granular type” as described by Kudo in 1993[16]. Other macroscopic type lesions were classified as the non 0-IIc type.

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression to estimate the association between macroscopic features (early stage neoplasm/cancer, 0-IIc or non 0-IIc) and clinicopathological data including gender, age, family history of FDR with CRC. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with Stata software (Version 9.0 for Windows, StataCorp LP. TX, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 2079 patients who underwent initial colonoscopy were screened; 1586 were enrolled in this study. Of 493 excluded patients, 297 were less than 50 years old, 84 had a past history of surgical resection for CRC, 62 had a past history of endoscopic treatment for colorectal neoplasm, 7 had a family history of familial adenomatous polyposis or hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, 4 had inflammatory bowel disease; and the rest were excluded because of the presence of either submucosal tumor, metastatic colorectal tumor or ischemic colitis.

Patient characteristics

The study consisted of 1586 patients, including 1002 (63.2%) men and 584 (36.8%) women, with median age 63 (range, 50-96) years. There were 159 (10.0%) patients with a family history of FDR with CRC.

Detected neoplasm during colonoscopy

In 579 patients (36.5%), there were no neoplastic lesions detected on the initial colonoscopy. Colorectal neoplasm was found in 1 007 (63.5%) patients, among whom 651 (41.0%) patients had only early stage neoplasm/cancer, 206 (13.0%) patients had only advanced cancer, and 150 (9.5%) patients had both (Table 1). Furthermore, 775 (48.9%) patients had at least one non 0-IIc lesion and 63 (4.0%) patients had at least one 0-IIc lesion. The prevalence of 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm was 4.6% (95% CI: 3.3-5.9) in men and 2.9% (95% CI: 1.5-4.3) in women. In terms of age, the prevalence was 4.1% (95%CI: 2.9-5.3) in men and 3.7% (95% CI: 2.1-5.3) in women. These data showed that there was no statistical difference in frequency of 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm among gender and age. In addition, there were 14 (8.8%) patients with 0-IIc lesions and a family history of FDR with CRC.

Table 1.

Initial colonoscopic findings of the patients

| Patients without neoplasm | 579 (36.5%) |

| Patients with neoplasm | 1007 (63.5%) |

| Patients with only early stage neoplasm/cancer | 651 (41.0%) |

| Patients with only advanced cancer | 206 (13.0%) |

| Patients with both early stage neoplasm/cancer and advanced cancer | 150 (9.5%) |

Association between early stage, non 0-IIc, 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm and variables

Univariate analysis demonstrated that gender, age, and the family history of FDR with CRC were significantly associated with the prevalence of early stage and non 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm. On multivariate analysis, gender and the family history of FDR with CRC were significantly correlated with early stage and non 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm, although there was no significant association between non 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm and age (Tables 2 and 3). Univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated that only a family history of FDR with CRC was significantly correlated with 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm, whereas gender and age were not found to be significant (Table 4). The OR of association between 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm and family history of FDR with CRC adjusted by gender and age was higher than that of non 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm (OR = 2.78, 95% CI: 1.49-5.16, P = 0.0031 vs OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.22-2.41, P = 0.0017).

Table 2.

Odds ratio (OR) for early stage colorectal neoplasm calculated by univariate and multivariate analyses

|

No. of early stage neoplasm |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

| (n = 801) | Crude OR | 95%CI | P-value | Adjusted OR | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 230 | 1 | 1.66-2.51 | <0.0001 | 1 | 1.64-2.50 | < 0.0001 |

| Male | 571 | 2.04 | 2.03 | ||||

| Age (yr) | |||||||

| < 60 | 248 | 1 | 1.04-1.58 | 0.018 | 1 | 0.96-1.47 | 0.11 |

| ≥ 60 | 553 | 1.29 | 1.19 | ||||

| Familyhistory of FDR with CRC | |||||||

| No | 701 | 1 | 1.25-2.46 | 0.001 | 1 | 1.31-2.61 | 0.000 |

| Yes | 100 | 1.76 | 1.85 | ||||

Table 3.

Odds ratio (OR) for non 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm calculated by univariate and multivariate analyses

|

No. of non 0-IIc lesions |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

| (n = 775) | Crude OR | 95%CI | P-value | Adjusted OR | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 221 | 1 | 1.65-2.50 | < 0.0001 | 1 | 1.63-2.49 | < 0.0001 |

| Male | 554 | 2.03 | 2.02 | ||||

| Age (yr) | |||||||

| < 60 | 240 | 1 | 1.03-1.57 | 0.023 | 1 | 0.95-1.45 | 0.14 |

| ≥ 60 | 535 | 1.27 | 1.18 | ||||

| Family history of FDR with CRC | |||||||

| No | 680 | 1 | 1.17-2.28 | 0.004 | 1 | 1.22-2.41 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 95 | 1.63 | 1.71 | ||||

Table 4.

Odds ratio (OR) for 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm calculated by univariate and multivariate analyses

|

No. of 0-IIc lesions |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

| (n = 63) | Crude OR | 95%CI | P-value | Adjusted OR | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 17 | 1 | 0.91-2.83 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.92-2.90 | 0.08 |

| Male | 46 | 1.61 | 1.63 | ||||

| Age (yr) | |||||||

| < 60 | 20 | 1 | 0.64-1.89 | 0.73 | 1 | 0.61-1.82 | 0.86 |

| ≥ 60 | 43 | 1.1 | 1.05 | ||||

| Family history of FDR with CRC | |||||||

| No | 49 | 1 | 1.46-5.04 | 0.004 | 1 | 1.49-5.16 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 14 | 2.72 | 2.78 | ||||

DISCUSSION

Colorectal neoplasm with superficial morphology is broadly classified into two types, such as polypoid type and non-polypoid type[8,13]. In terms of polypoid type neoplasm, the adenoma-carcinoma sequence has formed the rationale for CRC screening and prevention in Western countries[5,17]. In addition, it is also known that familial risk management is one of the important strategies for CRC prevention due to its associations with bowel malignancy[5] and adenoma growth[6,7]. Almendingen et al[7] reported a significant association between family history of FDR with CRC and adenoma growth (adjusted OR = 3.9, 95% CI: 1.2-13.4). In the present study, family history of FDR with CRC was significantly correlated with non 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm (OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.22-2.41, P = 0.0017), which tends to show a result similar to previous reports. However, these data are mainly based on the polypoid type colorectal neoplasm.

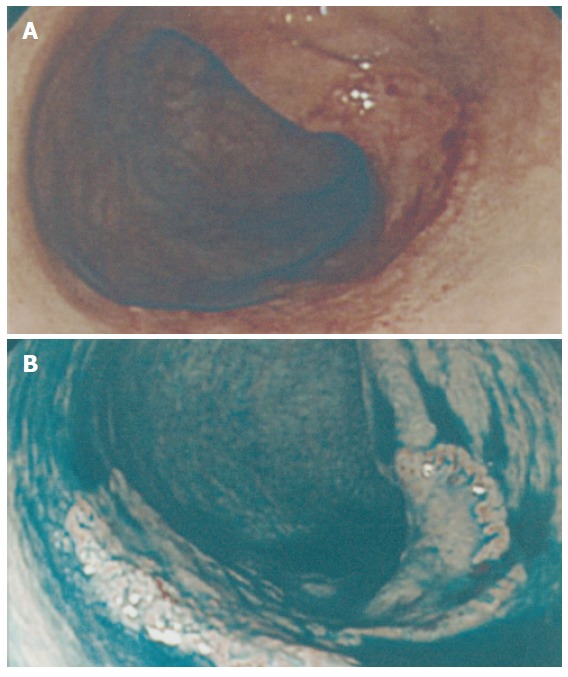

As the Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the colon proposed, special attention should be focused on depressed-type 0-IIc lesions[8], which are now widely recognized in Western countries as well as in Japan. This recognition has important implication, as the proportion of CRC is likely to be higher in these lesions than in other types, and these lesions tend to be more advanced at the time of diagnosis, despite being smaller[18-23]. Furthermore, it is certainly more difficult to detect 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm than polypoid type lesions during colonoscopy. They usually appear only as patches of erythema or irregularity of the mucosal fold (Figures 1 and 2), so colonoscopists should develop an understanding of the 0-IIc lesion[9]. At the same time, it is very important to identify risk factors for 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm, so if patients with some risk factors for these lesions undergo colonoscopy, we could be more alert to recognizing the lesions. However, it has not been reported whether the risk of 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm is correlated with any patient characteristics, including family history of FDR with CRC.

Figure 1.

Superficial depressed lesion (0-IIc). A: A superficial depressed lesion (0-IIc) of the transverse colon, 27 mm in diameter. Initially it was recognized as a broad patch of erythema and deformity of the haustrum. The patient demonstrated a family history of CRC. His mother had a past history of sigmoid colon cancer at age of 65 years. B: After dye spraying, an absolutely depressed area could be clearly identified, with a slightly elevated margin.

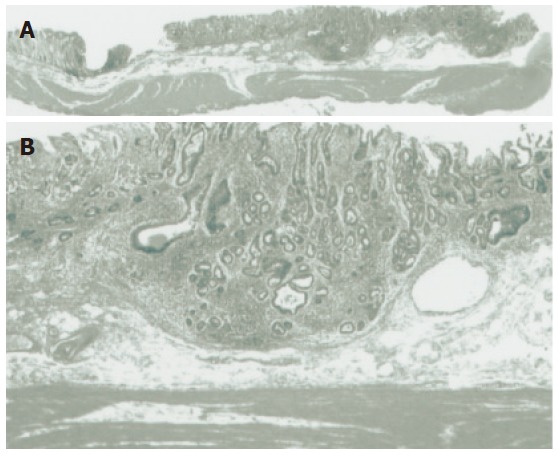

Figure 2.

Histological findings. A: Low-power histological view of a cut section of the resected specimen confirmed Dukes’ A (T1 stage) carcinoma with invasion to the submucosa. B: High-power histological view confirmed a well differentiated adenocarcinoma invading 1000 μm below the muscularis mucosa.

In the present study, 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm was

detected in 63 patients (4.0%), which is nearly similar to data (1.94%-5%) reported by other institutes in Japan[8,9]. More importantly, our study showed a significant correlation with family history of FDR with CRC and 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm (OR = 2.78, 95% CI: 1.49-5.16, P =0.0031), suggesting the possibility of a genetic contribution to the occurrence of 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm. Recently, two major pathways for colorectal neoplasm are highly suspected. Compared to the polypoid lesions arisen in the pathway of adenoma-carcinoma sequence, depressed-type (0-IIc) lesions are proposed to arise in de novo pathway and show rapid growth. Molecular biology also suggests that depressed-type lesions are likely to have early P53 and delayed K-ras mutations distinct from the former pathway[24,25]. Moreover, there tends to be high microsatellite instability occurrence in de novo cancers compared to early cancers with adenoma[25]. It is also noteworthy that Ricciardiello et al[26] have reported there is higher degree of microsatellite instability among patients with family history of FDR with CRC. These results may support our positive association between depressed-type colorectal neoplasm and family history of FDR with CRC. In addition, the pathway of depressed-type lesions evolving rapidly into a small flat invasive carcinoma is hypothesized to be a major route in hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC)[8], for which the genes hMSH2, hMLH1, and others have been identified as being responsible. In our study, multivariate analysis stratified by age showed higher OR of association between 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm and family history of FDR with CRC in patients before age of 60 years than those after age of 60 years (OR = 4.06, 95% CI: 1.48-11.14, P = 0.006 vs OR = 2.28, 95% CI: 1.02-5.06, P = 0.04), whereas our colleagues previously reported that depressed-type lesions were predominant in the right colon[27]. These characteristics are similar to HNPCC, and further molecular genetic research for depressed-type 0-IIc lesions and HNPCC is required. However, to our knowledge, the association between a family history of FDR with CRC and 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm has not been investigated previously even on NPS (National Polyp Study in USA). The limitation of this study is that the prevalence of patients with neoplasm in this study was higher (63.5%) than that in the general population because of a characteristic of our cancer center hospital, because even we selected the patients who undergo initial total colonoscopy at our hospital, many patients are introduced from general hospital for further examination because of suspicion of colorectal cancer. Although the statistical analysis in this study could avoid these biases, this association should be confirmed in a prospective multicenter study.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates a significant association between the family history of FDR with CRC and 0-IIc colorectal neoplasm. When patients with a family history of FDR with CRC undergo colonoscopy, colonoscopists should pay attention to not only polypoid, but also depressed-type (0-IIc) lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Tomonori Yano, Dr. Santa Hattori, Dr. Ayumu Hosokawa, Dr. Keiko Minashi, Dr. Keishi Yamashita, Dr. Chikatoshi Katada, Dr. Tsukasa Kaihara, Dr. Hirohisa Machida (Division of Digestive Endoscopy and Gastrointestinal Oncology, National Cancer Center Hospital East) for assistance with questionnaires and interviews, Dr. Motoki Iwasaki (Epidemiology and Prevention Division, Research Center for Cancer Prevention and Screening, National Cancer Center) and Dr. Manabu Muto (Division of Digestive Endoscopy and Gastrointestinal Oncology, National Cancer Center Hospital East) for valuable advice on statistical analysis.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Saito H. Screening for colorectal cancer: current status in Japan. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:S78–S84. doi: 10.1007/BF02237230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1669–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412223312501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien JM. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer: analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, by P. Lichtenstein, N.V. Holm, P.K. Verkasalo, A. Iliadou, J. Kaprio, M. Koskenvuo, E. Pukkala, A. Skytthe, and K. Hemminki. N Engl J Med 343: 78-84, 2000. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:167–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns LE, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2992–3003. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, Ganiats T, Levin T, Woolf S, Johnson D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Gerdes H, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Bond JH, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Panish JF. Risk of colorectal cancer in the families of patients with adenomatous polyps. National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:82–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601113340204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almendingen K, Hofstad B, Vatn MH. Does a family history of cancer increase the risk of occurrence, growth, and recurrence of colorectal adenomas. Gut. 2003;52:747–751. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3–S43. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sano Y, Tanaka S, Teixeira CR, Aoyama N. Endoscopic detection and diagnosis of 0-IIc neoplastic colorectal lesions. Endoscopy. 2005;37:261–267. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu KI, Sano Y, Kato S, Fujii T, Nagashima F, Yoshino T, Okuno T, Yoshida S, Fujimori T. Chromoendoscopy using indigo carmine dye spraying with magnifying observation is the most reliable method for differential diagnosis between non-neoplastic and neoplastic colorectal lesions: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1089–1093. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sano Y, Saito Y, Fu KI, Matsuda T, Uraoka T, Kobayashi N, Ito H, Machida H, Iwasaki J, Emura F, et al. Efficacy of Magnifying chromoendoscopy for the differential diagnosis of colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc. 2005;17:105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. WHO classification of tumours. Tumours of the digestive system. In: Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kudo S, Riboli E, Nakamura S, et al., editors. Carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- 13.General rules for clinical and pathological studies on cancer of the colon, rectum and anus. Part I. Clinical classification. Japanese Research Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Jpn J Surg. 1983;13:557–573. doi: 10.1007/BF02469505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka S, Haruma K, Oka S, Takahashi R, Kunihiro M, Kitadai Y, Yoshihara M, Shimamoto F, Chayama K. Clinicopathologic features and endoscopic treatment of superficially spreading colorectal neoplasms larger than 20 mm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:62–66. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaneko K, Kurahashi T, Makino R, Konishi K, Mitamura K. Growth patterns of superficially elevated neoplasia in the large intestine. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:443–450. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo S. Endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed types of early colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 1993;25:455–461. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muto T, Kamiya J, Sawada T, Konishi F, Sugihara K, Kubota Y, Adachi M, Agawa S, Saito Y, Morioka Y. Small "flat adenoma" of the large bowel with special reference to its clinicopathologic features. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:847–851. doi: 10.1007/BF02555490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujii T, Rembacken BJ, Dixon MF, Yoshida S, Axon AT. Flat adenomas in the United Kingdom: are treatable cancers being missed. Endoscopy. 1998;30:437–443. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rembacken BJ, Fujii T, Cairns A, Dixon MF, Yoshida S, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. Flat and depressed colonic neoplasms: a prospective study of 1000 colonoscopies in the UK. Lancet. 2000;355:1211–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitoh Y, Waxman I, West AB, Popnikolov NK, Gatalica Z, Watari J, Obara T, Kohgo Y, Pasricha PJ. Prevalence and distinctive biologic features of flat colorectal adenomas in a North American population. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1657–1665. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuda S, Veress B, Tóth E, Fork FT. Flat and depressed colorectal tumours in a southern Swedish population: a prospective chromoendoscopic and histopathological study. Gut. 2002;51:550–555. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Adam I, Shorthouse AJ, Brown S, Sanders DS, Lobo AJ. A prospective clinicopathological and endoscopic evaluation of flat and depressed colorectal lesions in the United Kingdom. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2543–2549. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller JD, Bethke B, Stolte M. Colorectal de novo carcinoma: a review of its diagnosis, histopathology, molecular biology, and clinical relevance. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:453–460. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0623-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yashiro M, Carethers JM, Laghi L, Saito K, Slezak P, Jaramillo E, Rubio C, Koizumi K, Hirakawa K, Boland CR. Genetic pathways in the evolution of morphologically distinct colorectal neoplasms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2676–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ricciardiello L, Goel A, Mantovani V, Fiorini T, Fossi S, Chang DK, Lunedei V, Pozzato P, Zagari RM, De Luca L, et al. Frequent loss of hMLH1 by promoter hypermethylation leads to microsatellite instability in adenomatous polyps of patients with a single first-degree member affected by colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:787–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konishi K, Fujii T, Boku N, Kato S, Koba I, Ohtsu A, Tajiri H, Ochiai A, Yoshida S. Clinicopathological differences between colonic and rectal carcinomas: are they based on the same mechanism of carcinogenesis. Gut. 1999;45:818–821. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.6.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]