Abstract

Background:

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction, especially delirium commonly occurs after cardiac surgery. Clinical evidences suggest an increase in delirium in opium abusers after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) surgery. In this study, the prevalence of delirium in addict (opium user) and nonaddict patients after CABG were compared.

Methods:

In a cross-sectional study after obtaining institutional approval and informed consent, 325 patients candidate for elective CABG were included in the study. All patients with history of opium abuse met the criteria for opioid dependence using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition definitions. Delirium after CABG was assessed in addict (opium user) and nonaddict patients up to a maximum of 5 days after surgery with the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist.

Results:

A total of 325 patients were evaluated (208 without and 117 with a history of opium abuse). Postoperative delirium occurred within 72 h after surgery in 44.31% of all patients. There was a significant difference in the prevalence of postoperative delirium between the opium users (80.7%) and nonaddict patients (25%) in the intensive care unit (P < 0.001). Opium addiction was a risk factor for postoperative delirium after CABG Surgery.

Conclusions:

Delirium after CABG surgery is more prevalent in opium users compared with nonaddict patients. Therefore, opium abuse is a possible risk factor for postoperative delirium in cardiac surgical patients.

Keywords: Addiction, cardiac surgery, delirium, intensive care unit, opium

INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a common complication of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, occurring in 32-73% of patients.[1] Postoperative delirium, which is an acute, usually temporary condition characterized by disorientation, hallucinations, anxiety, incoherent speech, restlessness, and delusions, is also associated with poor in-hospital outcomes, including increased length of hospital stay and higher mortality, than in patients without postoperative delirium.[2] Recognizing a patient's preoperative risk for delirium is crucial to detect delirium proactively and limit its severity or prevent it altogether.[3]

Opium abuse is a major type of drug abuse in Iran.[4] The prevalence of opium addiction in CABG patients is relatively high, and the majority of addicted patients are on this belief that opiates have positive effects on improvement of their chest pain and cardiovascular function.[5] Opioid receptors are distributed in the central nervous system (CNS)[6] and cause the effects of opium abuse on CNS such as drowsiness, dizziness, restlessness, headache, malaise, CNS depression, insomnia, and mental depression.[7] Some evidences explain delirium caused by opioid abuse.[8,9]

We found no study to identify opium addiction as a possible risk factor for postoperative delirium in cardiac surgical patients. Therefore in this study, we investigated the prevalence of delirium in addict (opium user) and nonaddict patients after CABG.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was approved by the heart disease center of the Chamran Hospital, Isfahan University of medical sciences, Isfahan, Iran. Written informed consent was taken from all subjects.

Participants

A total of 325 patients candidates for CABG surgery were included in the study. In the hospital setting, all patients had a clinical evaluation by an anesthesiologist the day before surgery. One hundred and seventy-seven of 325 patients scheduled for CABG surgery reported a history of opium abuse. Inclusion criteria were patients within 20-80 years of age, provided written informed consent, no history of psychosis, serum creatinine below 1.7 mg/dL, forced expiratory volume in 1 s and forced vital capacity over 80% of predicts in spirometry of 1 week before surgery by report of respiratory specialist were scheduled for elective CABG surgery with or without valve repair or replacement using cardiopulmonary bypass, without history of cerebrovascular accident within past 3 years of study, permanent ventricular pacing, or previously documented cognitive deficits, without hepatic impairment (aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase more than twice the upper normal limit) and chronic renal insufficiency (creatinine >2 mg/dL).

All patients with history of opium abuse met the criteria for opioid dependence using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) definitions.[10] All participants were screened for physical health and psychological history and were excluded if there was evidence of organic brain syndrome or preexisting dementia.

Procedure

Patients were operated according to the protocol of Cardiac Surgery and anesthesia professionals for CABG surgery. All patients were studied with similar conditions under the preoperative premedication with 10 mg morphine, 25 mg promethazine intramuscular and anesthetized with sodium thiopental induction with a dose of 5 mg/kg, pancronium with a dose of 1 mg/kg, fentanyl with intravenous doses of 4 μg/kg and lidocain with 1.5 mg/kg intravenously. The administration of anesthesia was done by 5/1-5/0 MAC isoflurane and oxygen with 100% concentration.

Delirium testing

Delirium was assessed in the intensive care unit (ICU) by using delirium screening checklist.[11] This is an 8-item (altered level of consciousness, inattention, disorientation, hallucination-delusion-psychosis, psychomotor agitation or retardation, inappropriate speech or mood, sleep/wake cycle disturbance, symptom fluctuation) checklist based on DSM-IV criteria and features of delirium. Raters completed the checklist based on data from the previous 24 h. Routinely, collected data (such as orientation) were combined with short observations of obvious manifestations of described features. The eight items are scored 1 (present) or 0 (absent) for a total of eight points. A score of four or greater was considered as a positive screen for delirium.[10] Delirium was monitored and reassessed up to a maximum of 5 days after surgery by three independent physicians.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive data were presented as mean ± standard error or n (%) where appropriate. To test for between-group differences, Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used for proportions and the Student's t-test was used for continuous outcomes. Logistic regression was used to predict the effect of variables related to delirium after CABG. P < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

A total of 325 patients were included in the study (208 without and 117 with a history of opium abuse). The mean age of patients was 58.76 years (9.02 standard deviation, range: 29-77 years) included 256 men (78.8%) and 69 women (21.2%).

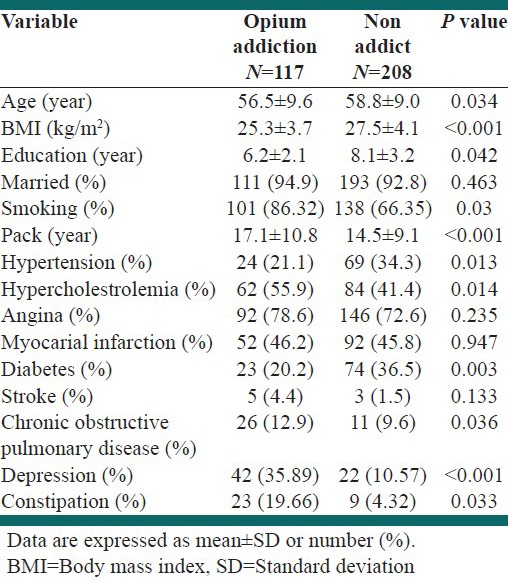

117 patients (36%) were opium user while 208 patients had not history of opium abuse. Men comprised 96.58% of the addicts in the age range 39-75 years. Nonaddicted individuals were in the age range 29-77 years. The demographic data of participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic variables in two evaluated groups

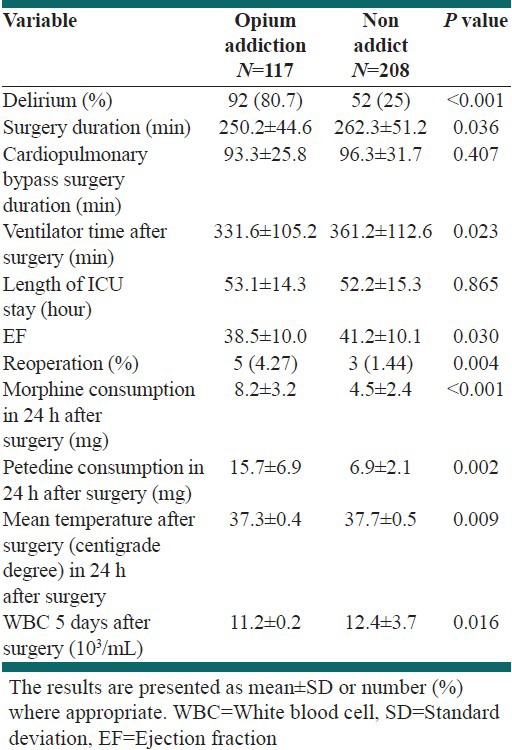

Delirium was assessed within 5 days after surgery. Postoperative delirium occurred within 72 h after surgery in 44.31% of patients. As shown in Table 2, there was a significant difference in the prevalence of postoperative delirium between the opium user (80.7%) and nonaddict patients (25%) in the ICU (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Surgical, pre- and post-operative care variables in patient with and without addiction

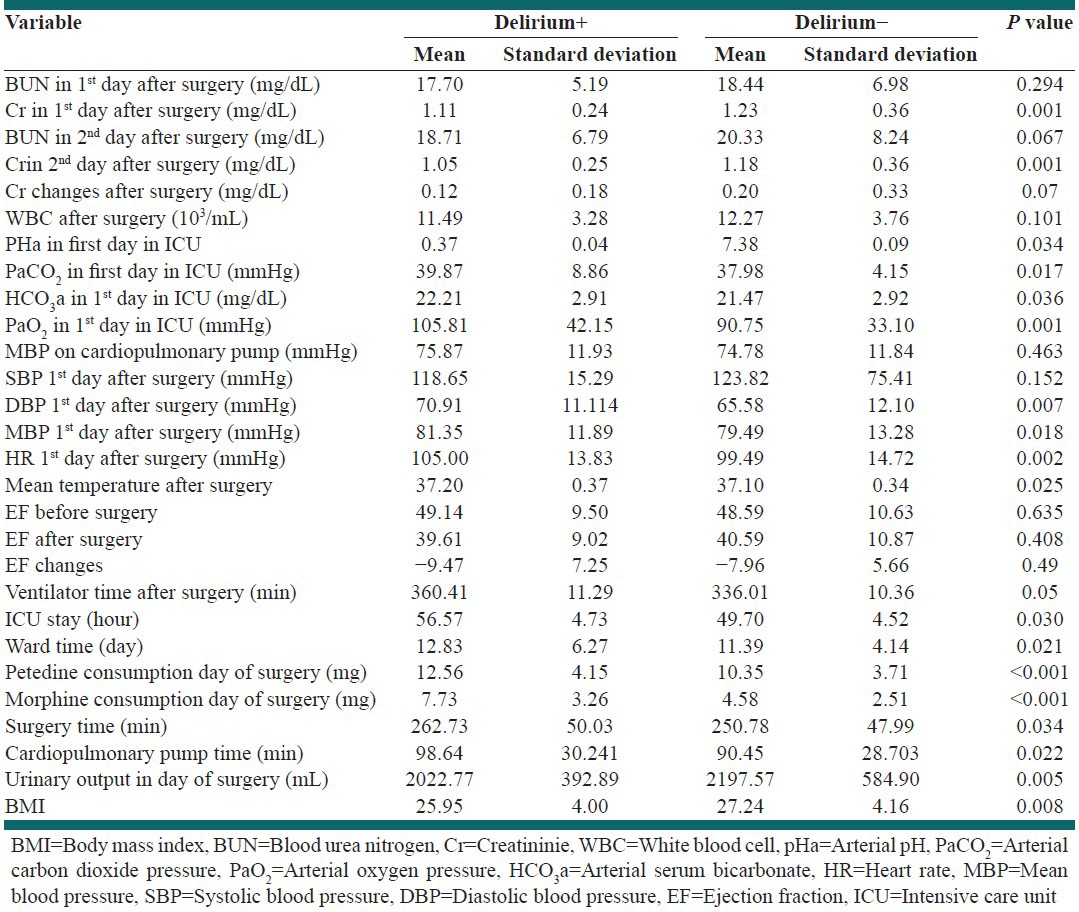

The patients’ mean creatinine in the 1st and 2nd day after surgery was different in patients with and without delirium. We found statically significant differences in patients’ mean body temperature after surgery, PaCO2, PaO2 and arterial pH in 1st day after surgery and ICU stay between patients with and without delirium [Table 3].

Table 3.

Surgical, anesthesia, and postoperative care data in patients with and without delirium

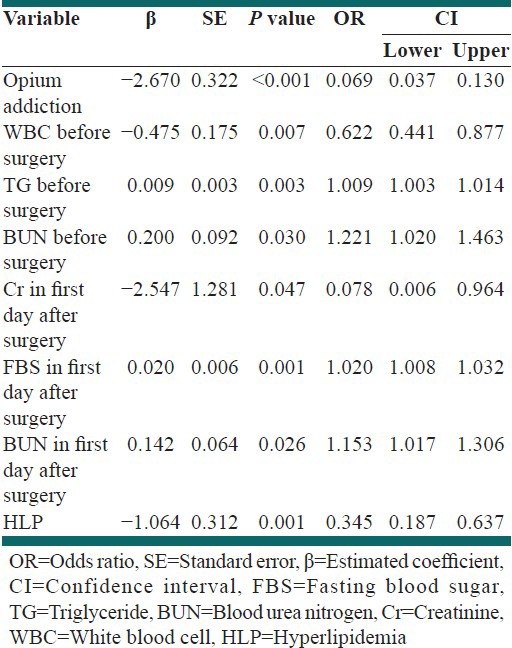

Logistic regression was used to assess the ability of eight independent variables (opium addiction, white blood cells before surgery, triglycerides [TG] before surgery, blood urea nitrogen [BUN] before surgery, creatinine, fasting blood sugar and BUN in first day after surgery and hyperlipidemia) to predict delirium incidence. In the final model, the overall accuracy percentage was 85% and all predictors were statistically significant, with opium abuse recording a higher beta value (β= –2.670, P < 0.05) than other variables [Table 4]. The nonaddict patients had 94% lower chance of affecting by delirium than addict patients. The patients BUN before surgery and in first day after surgery reserved the higher odds ratio, it implied that the patients with higher BUN before surgery affected by delirium 1.22 times more often than patients with lower BUN.

Table 4.

Prognostic value of surgical, pre- and post-operative care variables for delirium prediction

DISCUSSION

Research related to delirium after cardiac surgery is rare, the most health care providers do not fully understand the syndrome and etiology of delirium. Few studies have been proposed substance abuse as a risk factor for causing delirium after surgery and we found no study to identify opium abuse as a possible risk factor for postoperative delirium in cardiac surgical patients. However, clinical evidence suggests an increase in delirium, especially in opium users after CABG.

Opium abuse is a major predicament in many countries, particularly those in the Middle East.[12] Opium is not a pure substance. The alkaloids constitute about 25% by weight of opium and can be divided into two distinct chemical classes: Phenanthrene and benzylisoquinolines. The principal phenanthrenes are morphine (10% of opium), codeine (0.5%), and thebaine (0.2%). The principal benzylisoquinolines are papaverine (1%), which is a smooth muscle relaxant, and noscapine, the exact action of which is not clear.[13]

Delirium is one of the adverse effects of oxycodone and hydrocotarnine two alkaloids of opium.[9]

The total prevalence of delirium in our patients was 44.31% and it was similar to the range of previous findings (30-73%) among the prevalence of delirium after open heart surgical patients in ICUs.[14] However, the results of our study showed a significant increase in delirium rates in opium users (80.7%).

In some previous studies reported that history of psychological disorders like drug addiction and alcohol or sedative-hypnotic withdrawal (within the past month) as predisposing factors for delirium after surgery in ICU care.[15,16,17] Although delirium is considered as one of the symptoms of withdrawal syndrome in addicted patients after surgery in the intensive care unit, but the high incidence of delirium in addicted patients after surgery that is obtained in our study can’t be attributed only to withdrawal symptoms.

Based on previous studies, there is evidence that increased risk of atherosclerosis in patients is also associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass surgery.[18,19] Atherosclerosis is known to impair cognitive abilities, particularly in measures of frontal lobe function.[20] Delirium and atherosclerosis share common risk factors such as older age,[21] male sex,[22] and hypertension.[16] Also, in previous studies, there is evidence of increased atherosclerosis risk in opium consumers. Mohammadi et al. in a study that was conducted on animal models reported that levels of total cholesterol, TG, low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein were significantly different between nonaddict rabbits and addict rabbits, also production of ateromatous plaques was higher in addict rabbits significantly. They reported that the opium consumption can have aggravating effects in atherosclerosis formation related with hypercholesterolemia, mainly affecting lipid profile.[23] The studies of Davoodi et al. In 2005[24] Sadeghian et al.[25] in 2007 Azimzade-Sarwar et al. in 2005[26] also are expressed that opium consumption is effective at making ateromatous plaques. But the effect of opium use of cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in different studies is still controversial.

Shirani et al. in a study on 1339 patients in 2010, surveyed opium abuse as a risk factor for carotid stenosis in patients who candidate for CABG. Results showed the prevalence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension in opium user was clearly lower than those non users. As well as fasting blood glucose and HbA1C levels in opium users was significantly lower. But, there was no significant difference in lipid profile in both groups. However in another study, opium consumption was not considered as a risk factor for severe carotid artery stenosis.[27]

In Safaii and Kazemi study on short-term outcome of opium abuse in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, there were no significant difference of neurologic complications between opium users and nonusers.[28]

The endothelium or atherosclerotic plaques may be injured during surgery, increasing the risk of microemboli to the brain, leading to ischemia and enhanced risk of delirium.[17] Long-term opium consumption can also affect on the atherosclerotic plaque formation and can increase delirium by this mechanism.

Previous studies also found that patients with delirium after cardiac surgery had a significantly higher prevalence of emergency cardiac surgery than did patients without delirium. A possible explanation for this finding is that emergency surgical patients might have had inadequate psychological preparation before surgery.[17]

Substance abuse can be a cause of anxiety and depression. Previous studies show that depression is one of the clinical symptoms of opium addiction and significantly higher in addicts.[29] In our study, delirium was significantly higher in opium addicted patients than others. And this can be due to the increased prevalence of depression and consequently poor mental preparation before the operation in opium users, which can cause delirium after surgery.

Other factors more prevalent in patients with delirium than in patients without were older age, low educational level, single marital status, a history of psychological disorder, diabetes mellitus, and a history of stroke or renal disease. These results for predisposing factors are consistent with those of previous studies.[16,17,30] For example, predisposition to delirium in elderly patients has been related to decrease cerebral neuronal density, blood flow, metabolism, and levels of neurotransmitters.[31] But in our study, patients without history of opium use had older than opium users (P = 0.034). It shows opium abuse is a stronger risk factor for delirium after CABG than older age.

The results of our study showed that delirium after CABG is much greater in opium users. As we know delirium results in a 20-30% increase in morbidity and mortality rates[32,15] a decrease in cognitive and functional abilities, prolonged hospital stays, higher rates of discharge to nursing homes, rehabilitation, and increased costs.[33,34,35]

Further studies should be conducted for finding the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development and progression of delirium after cardiac surgery in opium users.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Researchers thank the personnel of ward and operating room of heart surgery of Chamran Hospital and heart center in Isfahan and also Dr Zahra Amini for completion of data analysis (Research project Number, 387007).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith LW, Dimsdale JE. Postcardiotomy delirium: Conclusions after 25 years? Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:452–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.4.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKhann GM, Grega MA, Borowicz LM, Jr, Bechamps M, Selnes OA, Baumgartner WA, et al. Encephalopathy and stroke after coronary artery bypass grafting: Incidence, consequences, and prediction. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1422–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.9.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Grande LJ, Milberg WP, King EG, Lipsitz LA, et al. Impaired executive function is associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:937–41. doi: 10.1111/J.1532-5415.2006.00735.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemati MH, Astaneh B, Ardekani GS. Effects of opium addiction on bleeding after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Report from Iran. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58:456–60. doi: 10.1007/s11748-010-0613-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abd Elahi MH, Forouznia S, Zare SA. Demographic characteristics of opioid addiction in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft. Tehran Univ Med J. 2007;64:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slamberová R. Opioid receptors of the CNS: Function, structure and distribution. Cesk Fysiol. 2004;53:159–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokhlesi B, Leikin JB, Murray P, Corbridge TC. Adult toxicology in critical care: Part II: Specific poisonings. Chest. 2003;123:897–922. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.3.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conde López VJ, Plaza Nieto JF, Macias Fernández JA, Losmozos Sánchez JA. Historical study of seven cases of delirium tremens in Spain in the first half of the XIX century. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines. 1995;23:200–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimoto T, Hisada A, Hasegawa T, Nozaki Y, Matoba M Symptom Control Research Group SCORE-G. Efficacy and safety of continuous subcutaneous injection of the compound oxycodone in cancer pain management: The first 4-year audit. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2009;36:1683–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Othmer E, Othmer SC. Fundamentals. 1st ed. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002. The Clinical Interview Using DSM-IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: Evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:859–64. doi: 10.1007/s001340100909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Department of State. The 2003 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) 2004. [Last accessed on 2004 Mar 1]. Available from: http://www.state.gov/p/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2003/

- 13.Gilman A, Goodman LS. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2000. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyer CB, Ashton CM, Teasdale TA. Postoperative delirium. A review of 80 primary data-collection studies. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:461–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parikh SS, Chung F. Postoperative delirium in the elderly. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:1223–32. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199506000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Delirium in an intensive care unit: A study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1297–304. doi: 10.1007/s001340101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winawer N. Postoperative delirium. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:1229–39. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pugh KG, Kiely DK, Milberg WP, Lipsitz LA. Selective impairment of frontal-executive cognitive function in African Americans with cardiovascular risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1439–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudolph JL, Babikian VL, Birjiniuk V, Crittenden MD, Treanor PR, Pochay VE, et al. Atherosclerosis is associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:462–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo HK, Lipsitz LA. Cerebral white matter changes and geriatric syndromes: Is there a link? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:818–26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.8.m818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, Ludwig LE, Muraca B, Haslauer CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271:134–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bellavance F. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:204–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammadi A, Darabi M, Nasry M, Saabet-Jahromi MJ, Malek-Pour-Afshar R, Sheibani H. Effect of opium addiction on lipid profile and atherosclerosis formation in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009;61:145–9. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davoodi G, Sadeghian S, Akhondzadeh S, Darvish S, Alidoosti M, Amirzadegan A. Comparison of specifications, short-term outcome and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction in opium dependent patients and non-dependents. Ger J Psychiatry. 2005;8:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadeghian S, Darvish S, Davoodi G, Salarifar M, Mahmoodian M, Fallah N, et al. The association of opium with coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:715–7. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328045c4e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azimzade-Sarwar B, Yousefzade G, Narooey S. A case-control study of effect of opium addiction on myocardialinfarction. Am J Appl Sci. 2005;2:1134–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shirani S, Shakiba M, Soleymanzadeh M, Esfandbod M. Can opium abuse be a risk factor for carotid stenosis in patients who are candidates for coronary artery bypass grafting? Cardiol J. 2010;17:254–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safaii N, Kazemi B. Effect of opium use on short-term outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58:62–7. doi: 10.1007/s11748-009-0529-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarighati S. An exploratory study on depression in Iranian addicts. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1980;26:196–9. doi: 10.1177/002076408002600307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koolhoven I, Tjon-A-Tsien MR, van der Mast RC. Early diagnosis of delirium after cardiac surgery. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:448–51. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lou MF, Yu PJ, Huang GS, Dai YT. Predicting post-surgical cognitive disturbance in older Taiwanese patients. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(03)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275:852–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milisen K, Abraham IL, Broos PL. Postoperative variation in neurocognitive and functional status in elderly hip fracture patients. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:59–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Ely EW, Burger C, Hopkins RO. Research issues in the evaluation of cognitive impairment in intensive care unit survivors. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2009–16. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inouye SK. The dilemma of delirium: Clinical and research controversies regarding diagnosis and evaluation of delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients. Am J Med. 1994;97:278–88. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]