Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate preoperative characteristics that distinguish favourable and unfavourable pathological and clinical outcomes in men with high biopsy Gleason sum (8 – 10) prostate cancer to better select men who will most benefit from radical prostatectomy (RP).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Institutional Review Board-approved institutional RP database (1982 – 2010) was analysed for men with high-Gleason prostate cancer on biopsy; 842 men were identified.

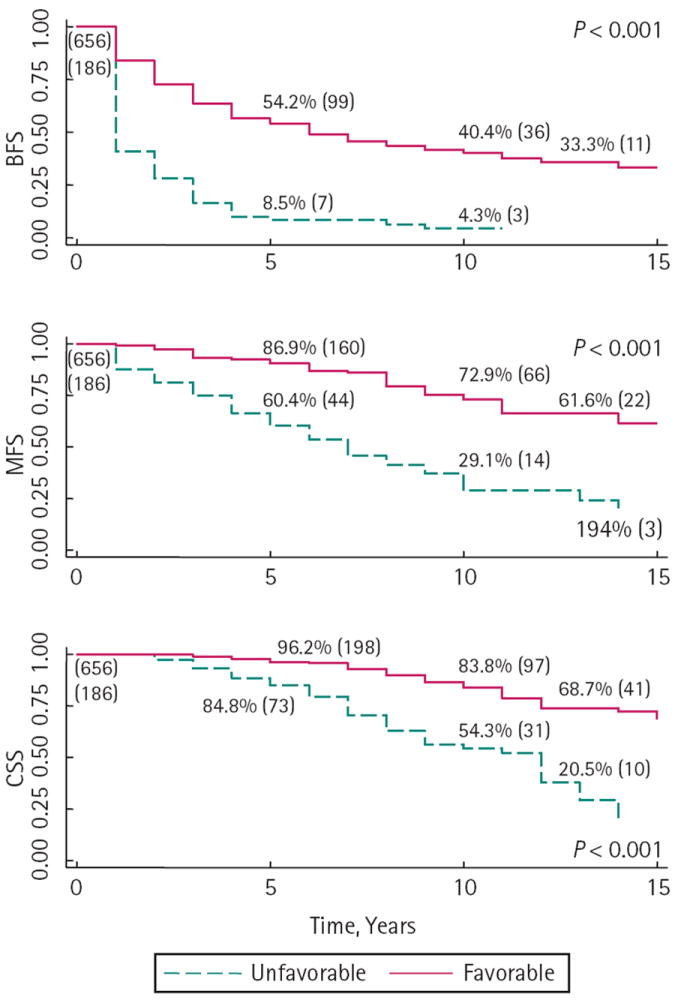

The 10-year biochemical-free (BFS), metastasis-free (MFS) and prostate cancer-specific survival (CSS) were calculated using the Kaplan – Meier method to verify favourable pathology as men with Gleason <8 at RP or ≤ pT3a compared with men with unfavourable pathology with Gleason 8 – 10 and pT3b or N1.

Preoperative characteristics were compared using appropriate comparative tests.

Logistic regression determined preoperative predictors of unfavourable pathology.

RESULTS

There was favourable pathology in 656 (77.9%) men. The 10-year BFS, MFS and CSS were 31.0%, 60.9% and 74.8%, respectively.

In contrast, men with unfavourable pathological findings had significantly worse 10-year BFS, MFS and CSS, at 4.3%, 29.1% and 52.3%, respectively (all P < 0.001).

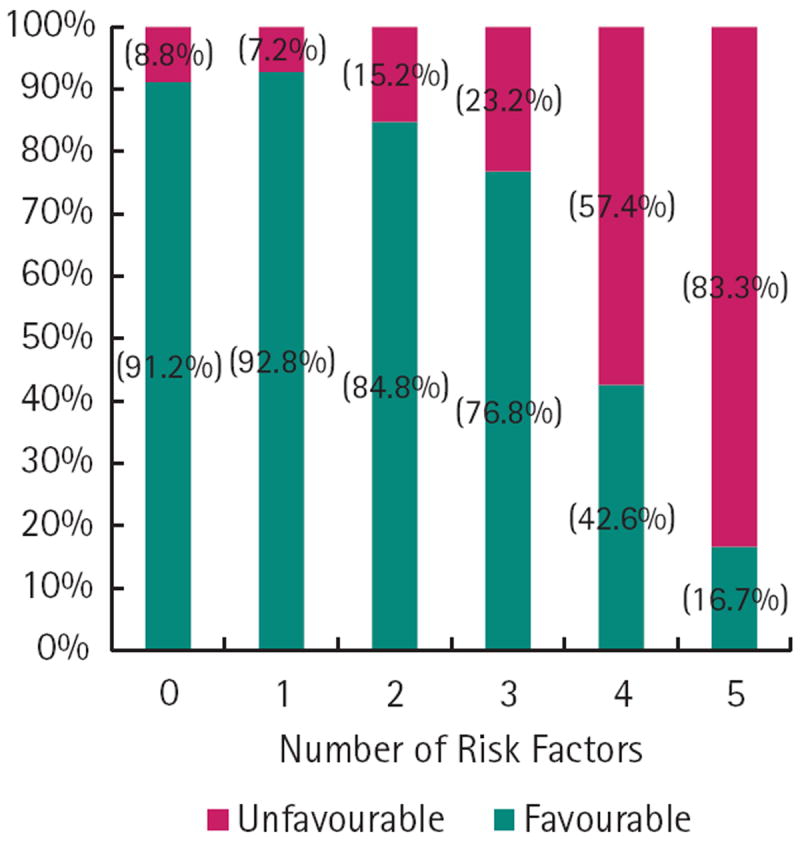

In multivariable logistic regression, a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentration of > 10 ng/mL (odds ratio [OR] 2.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.38 – 3.62, P = 0.001), advanced clinical stage (≥ cT2b; OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.55 – 4.21, P < 0.001), Gleason pattern 9 or 10 at biopsy (OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.59 – 4.09, P < 0.001), increasing number of cores positive with high-grade cancer (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.01 – 1.34, P = 0.04) and > 50% positive core involvement (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.17 – 4.35, P = 0.015) were predictive of unfavourable pathology.

CONCLUSIONS

Men with high-Gleason sum at biopsy are at high risk for biochemical recurrence, metastasis and death after RP; men with high Gleason sum and advanced pathological stage (pT3b or N1) have the worst prognosis.

Among men with high-Gleason sum at biopsy, a PSA concentration of > 10 ng/mL, clinical stage ≥ T2b, Gleason pattern 9 or 10, increasing number of cores with high-grade cancer and > 50% core involvement are predictive of unfavourable pathology.

Keywords: prostate cancer, high-risk, Gleason sum, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

For men undergoing radical prostatectomy (RP) for prostate cancer, biopsy and pathological Gleason sum are cited as the strongest predictors of outcome in pre- and postoperative models, respectively [1-5]. Although 80% of men with Gleason 8 – 10 prostate cancer undergoing RP at our institution have biochemical recurrence by 15 years, not all patients do uniformly poorly with respect to metastases-free (MFS) and prostate cancer-specific survival (CSS). A recent multivariate evaluation of long-term surgical outcomes in men with pathological Gleason sum 8 – 10 prostate cancer determined that pathological stage at RP was the most potent indicator of mortality [6]. Men with organ-confined (pT2) or extraprostatic (pT3a,) disease at RP had a 76 – 96% CSS at 15 year compared with 37 – 73% at 15 years for men with seminal vesicle invasion (pT3b, SVI) or lymph node involvement (N1) [6]. These divergent outcomes make the ideal management of high-Gleason sum prostate cancer controversial. While recent studies suggest that inclusion of surgery in the treatment of men with Gleason sum 8 – 10 on biopsy allows for better long-term outcomes when compared with radiation [7,8], many urologists are hesitant to subject these men to the side-effects of RP when benefit may be marginal.

Little data exists about the best preoperative criteria to identify men with high-Gleason sum prostate cancer who may benefit from surgery. One recent study suggests that men with a single high-risk feature (PSA concentration of > 20 ng/mL, Gleason 8 – 10 or clinical stage > cT2b [3]) have better outcomes than men with multiple high-risk features, but this work did not thoroughly explore the utility of individual preoperative parameters to predict advanced pathological stage [9]. In the present study, we evaluated the ability of preoperative characteristics, to predict favourable pathological and oncological outcomes in men found to have high Gleason sum at biopsy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Institutional Review Board-approved, Institutional RP Database of > 18 000 men from 1982 – 2010 was queried; 842 men with high-Gleason at biopsy who underwent RP were identified (who had not received neoadjuvant treatment). All men underwent pelvic lymph node dissection with an extended template as the institutional preference. Prior studies have shown pathological stage to be the strongest predictor of biochemical-free survival (BFS) and CSS in men with high biopsy Gleason sum; therefore we did not perform these analyses. Accordingly, we deemed men with a Gleason sum of < 8 or ≤ pT3a prostate cancer at RP to have ‘favourable’ disease and those with Gleason 8 – 10 and pT3b or N1 disease to have ‘unfavourable’ pathological findings [6]. The 10-year BFS, MFS and CSS were calculated using the Kaplan – Meier method by pathological stage. Biochemical recurrence was defined as a persistent PSA concentration of > 0.2 ng/mL after RP. Metastases were diagnosed by radiographic imaging. The CSS was defined as survival from death due to or attributed to complications of prostate cancer. Mortality data was collected from the Social Security Administration Death Index and cause of death was confirmed by the Center for Disease Control National Death Index information. The log-rank test and regression models were used to verify Gleason sum < 8 or ≤ pT3a as ‘favourable’ pathology at RP.

Preoperative characteristics were then compared using appropriate comparative tests (i.e. t -test, chi-squared, ANOVA) among those with favourable and unfavourable pathology. The biopsy slides that led to the diagnosis of cancer all underwent central pathological review at our institution, and various biopsy parameters were assessed in this study, including number of positive biopsy cores, maximum percentage involvement of each positive core (PPC), presence of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, perineural invasion, and bilateral disease. Also, tumour location (apex, mid-gland, base), if recorded by the urologist taking the biopsies, was also analysed. Univariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine preoperative predictors of unfavourable pathology. Positive predictors in univariate analysis were combined into multivariate analysis predicting unfavourable pathology.

RESULTS

Preoperative and pathological data for the 842 men with Gleason sum 8 – 10 on prostate biopsy is given in Tables 1 and 2, including detailed biopsy data. There was favourable pathology in 656 (77.9%) men. Notably, men with unfavourable pathology had a higher PSA concentration (9.2 vs 6.3 ng/mL, P < 0.001), more often had clinical stage ≥ cT2b (46.2% vs 22.4%, P < 0.001) and Gleason pattern 9 or 10 on biopsy (48.4% vs 22.9%, P < 0.001), had a greater proportion of men with cancer involving more than 3 cores (63% vs 48%, P = 0.002), with high-grade cancer involving > 1core (69% vs 50%, P < 0.001), with > 50% PPC of any core (88% vs 65%, P < 0.001) and a greater proportion of tumours at the base (91% vs 67%, P < 0.001). The 10-year BFS, MFS and CSS were 40.4%, 72.9% and 83.8% for men with favourable and 4.3%, 29.1% and 54.3% for unfavourable pathology, respectively (all P < 0.001, Fig. 1). The median (range) follow-up was 4 (1 – 22) years.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and pathological data for 468 men with Gleason 8 – 10 prostate cancer at biopsy with favourable (pT2 – pT3a) and unfavourable (pT3b or N1) pathology

| Variable | Biopsy Gleason 8 – 10 | Favourable | Unfavourable | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 842 | 656 (77.9) | 186 (22.1 | |

| Median (range): | ||||

| Age, years | 61 (38 – 76) | 61 (38 – 74) | 60 (38 – 76) | 0.4 |

| PSA concentration, ng/mL | 6.7 (0.1 – 84.1) | 6.3 (0.1 – 68) | 9.2 (0.1 – 84) | < 0.001 |

| N (%): | ||||

| Race: | 0.99 | |||

| African-American | 83 (9.9) | 65 (9.9) | 18 (9.7) | |

| Caucasian | 719 (85.4) | 560 (85.4) | 159 (85.5) | |

| Other | 40 (4.8) | 31 (4.7) | 9 (4.8) | |

| Clinical stage: | < 0.001 | |||

| T1a – T2a | 587 (69.7) | 493 (75.2) | 94 (50.5) | |

| T2b | 467 (55.5) | 111 (16.9) | 56 (30.1) | |

| T2c – T3 | 66 (7.8) | 36 (5.5) | 30 (16.1) | |

| Biopsy Gleason: | < 0.001 | |||

| 8 | 602 (71.5) | 507 (77.3) | 95 (51.1) | |

| 9 | 228 (27.1) | 143 (21.8) | 85 (45.7) | |

| 10 | 12 (1.4) | 7 (1.1) | 5 (2.7) | |

| Surgery: | 0.05 | |||

| laparoscopic RP | 34 (4.0) | 32 (4.9) | 2 (1.1) | |

| RA laparoscopic RP | 55 (6.5) | 40 (6.1) | 15 (8.1) | |

| retropubic RP | 752 (89.4) | 583 (89.0) | 169 (90.9) | |

| Year of surgery: | < 0.001 | |||

| 1982 – 1992 | 119 (14.1) | 74 (11.3) | 45 (24.2) | |

| 1993 – 2000 | 170 (20.2) | 134 (20.5) | 36 (19.4) | |

| 2000 – 2010 | 553 (65.7) | 448 (68.4) | 105 (56.5) | |

| Pathological Gleason: | < 0.001 | |||

| 6 | 26 (3.1) | 26 (4.0) | – | |

| 7 | 267 (31.7) | 267 (41.3) | – | |

| 8 | 252 (29.9) | 199 (30.8) | 53 (28.3) | |

| 9 | 279 (33.1) | 152 (23.5) | 127 (67.9) | |

| 10 | 7 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Pathological stage: | < 0.001 | |||

| OC (pT2) | 294 (34.9) | 294 (44.8) | – | |

| EPE (pT3a) | 329 (39.1) | 329 (50.2) | – | |

| SVI (pT3b) | 121 (14.4) | 20 (3.0) | 101 (54.3) | |

| LN metastases (N1) | 98 (11.6) | 13 (2.0) | 85 (45.7) | |

| Positive surgical margin | 209 (24.8) | 132 (20.1) | 77 (41.4) | < 0.001 |

RA, robot-assisted; OC, organ-confined; EPE, extraprostatic extension, LN, lymph node.

TABLE 2.

Biopsy characteristics of men with Gleason 8 – 10 prostate cancer with favourable (pT2 – pT3a) and unfavourable (pT3b or N1) pathology

| Biopsy Gleason 8 – 10 | Favourable | Unfavourable | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%): | 842 | 656 (77.9) | 186 (22.1) | |

| Biopsy Gleason: | ||||

| 8 | 602 (71.5) | 507 (77.3) | 95 (51.1) | |

| 3 + 5 | 54 (6.4) | 48 (7.3) | 6 (3.2) | |

| 4 + 4 | 414 (49.2) | 353 (53.8) | 61 (32.8) | |

| 5 + 3 | 14 (1.7) | 11 (1.7) | 3 (1.6) | < 0.001 |

| 9 | 228 (27.1) | 143 (21.8) | 85 (45.7) | |

| 4 + 5 | 138 (16.4) | 98 (14.9) | 40 (21.5) | |

| 5 + 4 | 45 (5.3) | 25 (3.8) | 20 (10.8) | |

| 10, 5 + 5 | 12 (1.4) | 7 (1.1) | 5 (2.7) | |

| Positive cores: | ||||

| Median (range) | 4 (1 – 16) | 3 (1 – 15) | 4.5 (1 – 16) | < 0.001 |

| 1 – 3, n (%) | 321 (49.2) | 273 (52.2) | 48 (36.9) | 0.002 |

| >, n (%)3 | 332 (50.8) | 250 (47.8) | 82 (63.1) | |

| High-grade cores: | ||||

| Median (range) | 2 (1 – 16) | 2 (1 – 10) | 2 (1 – 16) | < 0.001 |

| >1, n (%) | 353 (54.4) | 263 (50.3) | 90 (69.2) | < 0.001 |

| Total cores, median (range) | 12 (3 – 60) | 12 (3 – 60) | 12 (4 – 18) | 0.001 |

| Percentage cores positive, median (range) | 40 (5 – 100) | 31 (5 – 100) | 54 (8 – 100) | < 0.001 |

| PPC: | ||||

| Median (range) | 70 (5 – 100) | 60 (5 – 100) | 90 (25 – 100) | 0.065 |

| 0 to <50%, n (%) | 196 (30.3) | 181 (34.7) | 15 (12.0) | < 0.001 |

| ≥50 to 100%, n (%) | 450 (69.7) | 340 (65.3) | 110 (88.0) | |

| N (%): | ||||

| Positive core laterality: | ||||

| Bilateral | 209 (46.8) | 159 (25.6) | 50 (30.5) | |

| Right | 118 (26.4) | 98 (15.8) | 22 (13.4) | 0.4 |

| Left | 120 (26.8) | 98 (15.8) | 20 (12.2) | |

| Positive core location | ||||

| Apex | 254 (77.2) | 197 (75.8) | 57 (82.6) | 0.2 |

| Mid-gland | 258 (78.4) | 198 (76.2) | 60 (87.0) | 0.06 |

| Base | 237 (72.0) | 174 (66.9) | 63 (91.3) | < 0.001 |

| histologic features on biopsy: | ||||

| PNI | 207 (30.4) | 147 (26.9) | 60 (44.1) | < 0.001 |

| Atypia | 94 (13.8) | 77 (14.1) | 17 (12.5) | 0.6 |

| HGPIN | 108 (15.8) | 94 (17.2) | 14 (10.3) | 0.048 |

HGPIN, high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia; PNI, perineural invasion; PPN, maximum percentage involvement of each positive core.

FIG. 1.

Survival outcomes for men with Gleason 8 – 10 prostate cancer on biopsy by pathological stage and with favourable (Gleason < 8 or pT2 – pT3a) and unfavourable (Gleason 8 – 10 and pT3b or N1) pathology. The number at risk is shown in parenthesis at each time point.

In univariate logistic regression, a PSA concentration of > 10 ng/mL, clinical stage, biopsy Gleason pattern 5, number of positive cores, number of positive high-grade cores, > 50% PPC, perineural invasion and year of surgery (defined as the pre-PSA era [1982 – 1992], early PSA-era [1993 – 2000] and contemporary PSA-era [2001 – 2011]) were all significant predictors of unfavourable pathology. In multivariable logistic regression, a PSA concentration of > 10 ng/mL, clinical stage ≥ T2b, Gleason pattern 9 or 10, increasing number of cores with high-grade cancer and > 50% core involvement were predictive of unfavourable pathology. The likelihood of unfavourable pathology at RP increased with the number of these adverse features (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The likelihood of having favourable and unfavourable pathology with accumulating adverse features in men with Gleason 8 – 10 prostate cancer at biopsy.

In all, 230 (27.3%) men underwent additional (either adjuvant or salvage) hormone, radiation or chemotherapy at a median (range) of 3 (1 – 19) years after RP, with 93 (50%) men having unfavourable pathology receiving additional therapy, as compared with 137 (20.9%) of men with favourable disease (P < 0.001). Of the 82 men receiving adjuvant therapy, 31 received hormones, 34 received radiation and 17 received adjuvant hormones and radiation.

DISCUSSION

Men with prostate cancer are often generalised into low-, intermediate- and high-risk of recurrence based on preoperative characteristics [3]. In the contemporary era, with the incorporation of widespread PSA screening, high-risk disease is most commonly encompassed by men with Gleason 8 – 10 prostate cancer [10], who are considered to do uniformly poorly. The present study confirms previous studies [6,11], showing divergent outcomes for men with high-Gleason prostate cancer and that select men may benefit from RP. In addition, the present analysis identified preoperative characteristics, specifically in men with high-grade disease that predict favourable outcomes.

There were significant differences in BFS, MFS and CSS for men with favourable and unfavourable pathology at RP. This leads to a few points of clinical importance. First, men with Gleason 8 – 10 disease should be counselled to expect biochemical recurrence as part of the management of their chronic disease process. Second, the distinction between favourable (Gleason < 8 or ≤ pT3a) and unfavourable pathology (Gleason 8 – 10 and pT3b or N1) provides clinically meaningful information regarding MFS and death from prostate cancer. Finally, as biochemical recurrence occurs in most men, more meaningful clinical endpoints (i.e. adjuvant therapy, time to metastases, morbidity from treatment and mortality) should be discussed among clinicians and with patients.

As outcomes were strongly linked to pathological features at RP, criteria that distinguish favourable or unfavourable disease were extrapolated from available preoperative data: namely PSA concentration, clinical stage and biopsy characteristics. Since its inception, an elevated PSA concentration has been associated with worse pathological stage, biochemical recurrence after RP and response to radiation treatment [3-5]. It is no surprise, therefore, that an elevated PSA concentration in men with Gleason 8 – 10 on biopsy is associated with unfavourable pathology at RP. A high PSA concentration (> 10 ng/mL in the present series) may be a surrogate for tumour volume and therefore represent an under sampling of total volume of malignancy in the prostate. This may reflect shortcomings inherent to needle biopsy or cancers in the transition zone or anterior of the prostate not reached by a standard biopsy schema. An elevated PSA concentration as a poor prognostic indicator in high-Gleason disease also has repercussions for screening, hinting that capturing men with high-Gleason disease with a lower PSA concentration may correlate to improved stage and survival. Similarly, men diagnosed with advanced clinical stage by DRE, indicates a higher likelihood of unfavourable pathology and outcome. Prior studies have shown the accumulation of high-risk features to predict these outcomes.

Not unexpectedly, the presence of Gleason pattern 5 at biopsy increased the likelihood of unfavourable pathology and subsequent metastases and death from prostate cancer. Previous post-RP series implicate Gleason sum as the strongest predictor of cancer-related outcomes [1,2]. This is considered to be due to the aggressive biological behaviour of the disease and the risk of occult systemic disease with 40 – 100% of men with Gleason 8 – 10 disease having lymph node involvement [12,13].

The last criteria predictive of unfavourable pathology was a greater the number of high-Gleason cores involved with cancer and > 50% PPC of any core. Together, PSA concentration, clinical stage, and the criteria indicate that tumour volume is important in determining the extent of high-Gleason disease. Several authors have investigated the role of tumour volume in prognosis after RP with conflicting results [14-18]. Once again, these studies examined large and small tumours in low-, intermediate- and high-Gleason disease and we contend that large, Gleason 8 – 10 tumours may have different biological behaviour patterns than a large, Gleason 6 lesion.

As most men with Gleason 8 – 10 disease recur biochemically, counselling these men about their risk of subsequent treatment, related morbidities and the probability of death from prostate cancer becomes paramount. More than twice the proportion of men with unfavourable disease received additional treatment compared with those with favourable disease after RP in the present series. We support the use of adjuvant radiation only in men with positive surgical margins without SVI [19,20] and initiate androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) only upon the appearance of radiographically confirmed metastases [21,22]. However, this provides a strong surrogate for the number of patients who advance to metastatic disease and parallels the MFS analysis which is significantly worse for men with unfavourable pathology. Men who receive additional therapies are subject to a small but significant risk of side-effects from radiation therapy and ADT, which may include worse urinary symptoms, bowel irritation, cognitive decline and an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among others [23-25]. Due to the significantly better survival for men with favourable pathology (pT2/pT3a disease), the present data suggest the judicious use of adjuvant therapies in men with favourable pathology encouraged by other groups. Supporting this, adjuvant radiation therapy has been shown to have little benefit in men with pT3a, margin negative disease [19] and also subjects men to the side-effects of radiation without apparent benefit. Salvage radiation therapy and/or ADT, on the other hand, show a clear survival benefit for selected men with recurrence and may extend the time period for multimodality treatments and side-effects [26].

In addition to suggesting a population with high risk disease that might be spared adjuvant therapy, the present study also identifies those men who will go on to have unfavourable pathology and outcomes despite optimal current therapy. This population might be counselled to avoid RP as part of their treatment regimen as the side-effects and recovery time after RP may outweigh its added benefit. Alternatively, as recent studies indicate that men at high risk may derive survival advantage from the inclusion of primary surgery relative to radiation therapy [7,8], these men with unfavourable preoperative features may represent the sub-population in which novel neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments should be tested most aggressively.

The obvious limitation of the present study lies in its retrospective, post-surgical design and relatively short median follow-up (4 years). However, it should be noted that the short median follow-up may reflect the relatively high-rate at which these patients recur (and are censored) after intervention. However, the strength of the present study is the correlation of biopsy characteristics to pathological outcomes in a large cohort, which studies of radiation or hormone treatment could not provide. Of note, as a tertiary referral centre, not every biopsy slide is sent or received for analysis and therefore potential bias exists, as in some cases only slides with cancer were available for review. In these instances, only data that could be confirmed was analysed (i.e. Gleason grade, percentage involvement, etc.) and incomplete data (i.e. number of cores) were excluded. Additionally, the present cohort is subject to surgeon-specific selection bias and most likely overestimates CSS in the general population with high-Gleason prostate cancer. However, it does provide a clear expectation for men who present with certain preoperative characteristics and undergo RP. It should be recognised that the stage and grade migration have occurred in prostate cancer, along with the definitions of Gleason grade. Importantly, the present cohort of high-Gleason men is relatively homogenous and contemporary with most of the biopsies taken within the last decade. Also, most grade migration has occurred in low- and intermediate-risk patients; while no data has clearly shown that new Gleason 8 cancers are less aggressive than old Gleason 8 cancers. Additionally, strong treatment recommendations about RP vs other treatments cannot be gleaned from the present data. The present criteria certainly identify men who will do relatively well or poorly when compared with others undergoing RP. The best treatment for high-Gleason prostate cancer is yet to be determined and probably involves multimodal treatment. While the biomolecular explanation for improved oncological outcomes for men with favourable disease needs further investigation, the implications of the present study are clear: men with large-volume, high-Gleason disease (either by clinical examination, biopsy criteria or high PSA concentration as a surrogate for tumour volume) have an increased risk of having unfavourable, advanced prostate cancer and dying from the disease.

In conclusion, while most men with high-Gleason prostate cancer will recur biochemically, men with favourable (Gleason < 8 or ≤ pT3a) pathology had prolonged MFS and CSS when compared with men with unfavourable (Gleason 8 – 10 and pT3b or N1) disease. Predictors of unfavourable disease include a PSA concentration of > 10 ng/mL, clinical stage ≥ T2b, Gleason pattern 9/10, increasing number of cores with high-grade cancer and > 50% core involvement.

What’s known on the subject? and What does the study add?

Men with high-risk prostate cancer experience recurrence, metastases and death at the highest rate in the prostate cancer population. Pathological stage at radical prostatectomy (RP) is the greatest predictor of recurrence and mortality in men with high-grade disease. Preoperative models predicting outcome after RP are skewed by the large proportion of men with low- and intermediate-risk features; there is a paucity of data about preoperative criteria to identify men with high-grade cancer who may benefit from RP.

The present study adds comprehensive biopsy data from a large cohort of men with high-grade prostate cancer at biopsy. By adding biopsy parameters, e.g. number of high-grade cores and > 50% involvement of any core, to traditional predictors of outcome (prostate-specific antigen concentration, clinical stage and Gleason sum), we can better inform men who present with high-grade prostate cancer as to their risk of favourable or unfavourable disease at RP.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by SPORE grant P50CA58236 from the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute. P.M.P. and A.E.R. are supported by Award Number T32DK007552 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Abbreviations

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- MFS

metastases-free survival

- CSS

cancer-specific survival

- SVI

seminal vesicle invasion

- BFS

biochemical-free survival

- PPC

percentage involvement of each positive core

- ADT

androgen-deprivation therapy

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

References

- 1.Grossfeld GD, Latini DM, Lubeck DP, Mehta SS, Carroll PR. Predicting recurrence after radical prostatectomy for patients with high risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pound CR, Partin AW, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Prostate-specific antigen after anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. Patterns of recurrence and cancer control. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28:555–65. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Partin AW, Yoo J, Carter HB, et al. The use of prostate specific antigen, clinical stage and Gleason score to predict pathological stage in men with localized prostate cancer. Journal Urol. 1993;150:110–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierorazio PM, Guzzo TJ, Han M, et al. Long-term survival after radical prostatectomy for men with high gleason sum in pathologic specimen. Urology. 2010;76:715–21. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelefsky MJ, Eastham JA, Cronin AM, et al. Metastasis after radical prostatectomy or external beam radiotherapy for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer: a comparison of clinical cohorts adjusted for case mix. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1508–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdollah F, Sun M, Thuret R, et al. A Competing-Risks Analysis of Survival After Alternative Treatment Modalities for Prostate Cancer Patients: 1988-2006. Eur Urol. 2010;59:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeb S, Schaeffer EM, Trock BJ, Epstein JI, Humphreys EB, Walsh PC. What Are the Outcomes of Radical Prostatectomy for High-risk Prostate Cancer? Urology. 2010;76:710–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Mehta SS, Carroll PR. Time trends in clinical risk stratification for prostate cancer: implications for outcomes (data from CaPSURE) J Urol. 2003;170:S21–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000095025.03331.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bastian PJ, Gonzalgo ML, Aronson WJ, et al. Clinical and pathologic outcome after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer patients with a preoperative Gleason sum of 8 to 10. Cancer. 2006;107:1265–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chodak GW, Thisted RA, Gerber GS, et al. Results of conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:242–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401273300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partin AW, Lee BR, Carmichael M, Walsh PC, Epstein JI. Radical prostatectomy for high grade disease: a reevaluation 1994. J Urol. 1994;151:1583–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Yemoto CM, Sigal BM, Johnstone IM. Biological determinants of cancer progression in men with prostate cancer. JAMA. 1999;281:1395–400. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.15.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May M, Siegsmund M, Hammermann F, Loy V, Gunia S. Visual estimation of the tumor volume in prostate cancer: a useful means for predicting biochemical-free survival after radical prostatectomy? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:66–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolters T, Roobol MJ, van Leeuwen PJ, et al. Should pathologists routinely report prostate tumour volume? The prognostic value of tumour volume in prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2010;57:821–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuchi E, Scardino PT, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM, Ohori M. Is tumor volume an independent prognostic factor in clinically localized prostate cancer? J Urol. 2004;172:508–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000130481.04082.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vollmer RT. Percentage of tumor in prostatectomy specimens: a study of American Veterans. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:86–91. doi: 10.1309/AJCPX5MAMNMFE6FQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Kwast TH, Bolla M, Van Poppel H, et al. Identification of patients with prostate cancer who benefit from immediate postoperative radiotherapy: EORTC 22911. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4178–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiegel T, Bottke D, Steiner U, et al. Phase III postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy compared with radical prostatectomy alone in pT3 prostate cancer with postoperative undetectable prostate-specific antigen: ARO 96-02/AUO AP 09/95. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2924–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loblaw DA, Virgo KS, Nam R, et al. Initial hormonal management of androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate cancer: 2006 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1596–605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh PC. Urological oncology: prostate cancer: editorial comment on: intermittent androgen deprivation for locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer: results from a randomised phase 3 study of the South European Uroncological Group. J Urol. 2009;182:2728. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matzinger O, Duclos F, van den Bergh A, et al. Acute toxicity of curative radiotherapy for intermediate- and high-risk localised prostate cancer in the EORTC trial 22991. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2825–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson CJ, Lee JS, Gamboa MC, Roth AJ. Cognitive effects of hormone therapy in men with prostate cancer: a review. Cancer. 2008;113:1097–106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, et al. Survival following primary androgen deprivation therapy among men with localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2008;300:173–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trock BJ, Han M, Freedland SJ, et al. Prostate cancer-specific survival following salvage radiotherapy vs observation in men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2008;299:2760–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]