Abstract

Although treatment options for men with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) have improved with the recent and anticipated approvals of novel immunotherapeutic, hormonal, chemotherapeutic and bone-targeted agents, clinical benefit with these systemic therapies is transient and survival times remain unacceptably short. Thus, we devote the second section of this two-part review to discussing emerging therapeutic paradigms and research strategies that are entering phase II and III clinical testing for men with metastatic CRPC. We will discuss a range of emerging hormonal, immunomodulatory, antiangiogenic, epigenetic and cell survival pathway inhibitors in current clinical trials, with an emphasis on how these therapies may complement our existing treatment options.

Keywords: castrate-resistant prostate cancer, novel therapies, clinical trials, drug development

Introduction

Although we now have four therapies that have been shown to extend survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) (docetaxel, cabazitaxel, sipuleucel-T and abiraterone acetate), none of these approaches are curative. To this end, annual mortality rates from prostate cancer in the United States remain unacceptably high at ~30 000 deaths per year.1 For this reason, the discovery of novel treatment strategies for this patient population remains a critical endeavor and the identification of alternative therapeutic targets has never been more actively pursued. Because exploitation of the androgen axis and the antitumor immune response has yielded fruit in recent years, several drug development efforts continue to focus on these avenues. This has resulted in the progression to phase III development of several novel androgen-directed agents (for example, orteronel, MDV3100) and immune-modulating drugs (for example, ipilimumab).

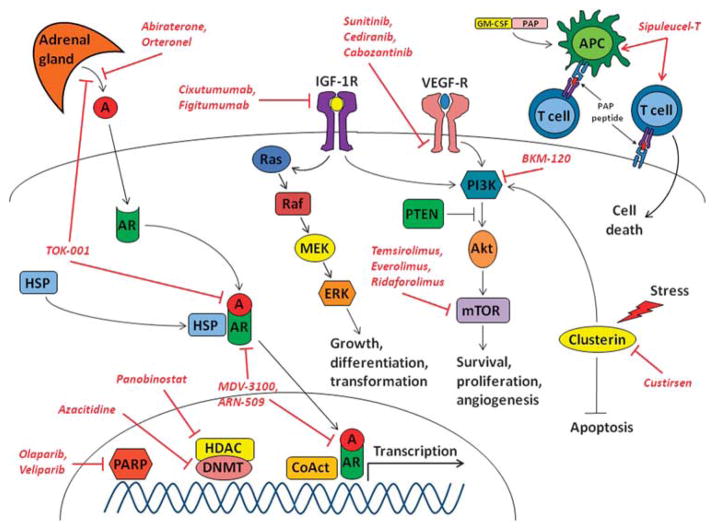

In addition to these strategies, our recently accelerated understanding of other biological and cellular processes driving prostate cancer progression and metastasis has fueled the preclinical and clinical exploration of myriad molecular targets comprising alternative oncogenic pathways (Figure 1). Such cellular processes reflect the basic hallmarks of cancer and include angiogenesis and tumor microenvironment interactions, cell growth and proliferation, apoptosis, cell nutrition, DNA repair and epigenetic regulation.2 This review is the second article in a series of two papers discussing therapeutic strategies for CRPC. Although the first review focused on Food and Drug Administration approved and available treatment options for these patients, this review will touch upon several novel therapies currently in clinical development that may enter the therapeutic arsenal in the next 5 years. Such therapies include additional androgen-modulating approaches, novel immunotherapies, angiogenesis inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway inhibitors, apoptosis-inducing drugs, insulin-like growth factor (IGF) pathway antagonists, epigenetic therapies and poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Promising pathways and targets in metastatic CRPC. A; androgen; AR, androgen receptor; APC, antigen-presenting cell; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; CoAct, transcriptional coactivators; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage-colony-stimulating factor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HSP, heat-shock protein; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor receptor-1; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PAP, prostatic acid phosphatase; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome ten; VEGF-R, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Novel androgen-directed approaches for metastatic CRPC

The first review in this two-part series discussed the oral agent abiraterone, a drug that suppresses extra-gonadal androgen synthesis by inhibiting CYP17 (C17,20-lyase and 17α-hydroxylase). This review will outline some additional androgen receptor (AR)-directed therapies that may hold promise in the near future.

Orteronel

Orteronel (TAK-700) is an oral, non-steroidal, selective CYP17 blocker that is a more potent inhibitor of C17,20-lyase activity than 17α-hydroxylase activity, leading to the suppression of extra-gonadal (autocrine, paracrine, adrenal) androgen biosynthesis without impairing cortisol production at the doses studied3 (Figure 1). This has the theoretical advantage of preventing ACTH feedback upregulation and avoiding complications related to secondary mineralocorticoid excess (hypertension, fluid retention, hypokalemia and need for corticosteroids). Moreover, orteronel is able to inhibit C17,20-lyase activity at lower nanomolar concentrations than abiraterone.4 Also, the use of a non-steroidal moiety minimizes the risks of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic effects, as well as the formation of steroidal metabolites that might have AR agonistic activity.

In a phase I/II study using orteronel in patients with metastatic CRPC (one-third of which had previous ketoconazole treatment), 52% of men receiving daily doses of ≥600 mg showed ≥50% PSA reductions (including 29% of men who showed ≥90% PSA declines).5 Importantly, the incidence of hypertension and hypokalemia in this trial was low, supporting the notion of preferential inhibition of C17,20-lyase over 17α-hydroxylase in human beings. Common toxicities observed with orteronel included fatigue (47%), emesis (30%), constipation (21%) and anorexia (12%). Based on the initial promising activity of this agent, a larger phase II trial of orteronel (without prednisone) in non-metastatic CRPC and two multicenter randomized phase III trials in metastatic CRPC were launched.

The first phase III study (C21004) will compare orteronel plus prednisone against placebo plus prednisone in patients with chemotherapy-naïve metastatic CRPC, whereas the second study (C21005) will investigate the same treatment arms in patients with metastatic CRPC that have progressed during or after docetaxel-based chemotherapy (Table 1). Both trials have been powered to detect a 20–25% improvement in overall survival between treatment groups. Preliminary results suggest that orteronel (with or without prednisone) may emerge as an alternative to abiraterone acetate in the future. Although the theoretical lack of requirement for prednisone is appealing given the recent approval of sipuleucel-T immunotherapy (which is probably most effective without concurrent immunosuppressive steroids), both of the ongoing phase III programs have utilized the combination of orteronel with prednisone, and future studies of orteronel without prednisone will be needed to clarify its single-agent utility in CRPC.

Table 1.

Selected ongoing phase II and III clinical trials of novel targeted therapies for men with metastatic CRPC

| Target/pathway | Agent | Phase | Treatment arm(s) | 1ary end point | Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR-directed approaches | |||||

| CYP17 (androgen synthesis) | Orteronel | III | Randomized trial: orteronel 400 mg orally twice daily vs placebo orally twice daily (post-docetaxel) | Overall survival | NCT01193257 |

| III | Randomized trial: orteronel 400 mg orally twice daily vs placebo orally twice daily (pre-docetaxel) | Overall survival and progression-free survival (co-primary) | NCT01193244 | ||

| TOK-001 | I/II | Single-arm trial: TOK-001 650–2600 mg orally daily (dose escalation) (pre-docetaxel) | Phase I: Safety Phase II: ≥50% PSA ↓ |

NCT00959959 | |

| AR | MDV3100 | III | Randomized trial: MDV3100 160 mg orally daily vs placebo orally daily (post-docetaxel) | Overall survival | NCT00974311 |

| III | Randomized trial: MDV3100 160 mg orally daily vs placebo orally daily (pre-docetaxel) | Overall survival and progression-free survival (co-primary) | NCT01212991 | ||

| ARN-509 | I/II | Single-arm trial: ARN-509 30–300 mg orally daily (dose escalation) (pre- and post-docetaxel) | Phase I: Safety Phase II: Time to PSA progression (≥25% ↑) |

NCT01171898 | |

| Immunotherapies | |||||

| CTLA-4 (immune checkpoint) | Ipilimumab | III | Randomized trial: bone irradiation, then ipilimumab 10 mg/kg i.v. every 3 weeks vs placebo i.v. every 3 weeks (post-docetaxel) | Overall survival | NCT00861614 |

| III | Randomized trial: ipilimumab 10 mg/kg i.v. every 3 weeks vs placebo i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | Overall survival | NCT01057810 | ||

| Other targeted therapies | |||||

| VEGF-R (angiogenesis) | Sorafenib | II | Single-arm trial: sorafenib 400 mg orally twice daily (post-docetaxel) | Time to disease progression | NCT00414388 |

| II | Single-arm trial: sorafenib 400 mg orally twice daily plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | ≥50% PSA ↓ | NCT00589420 | ||

| Cediranib | II | Randomized trial: cediranib 20 mg orally daily plus dasatinib 100 mg orally daily vs cediranib 20 mg orally daily (post-docetaxel) | Progression-free survival | NCT01260688 | |

| Ramucirumab | II | Randomized trial: cixutumumab (see below) 6 mg/kg i.v. every 1 week plus mitoxantrone 12 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks vs ramucirumab 6 mg/kg i.v. every 1 week plus mitoxantrone 12 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (post-docetaxel) | Progression-free survival | NCT00683475 | |

| VEGF-Trap (angiogenesis) | Aflibercept | III | Randomized trial: aflibercept 6 mg/kg i.v. plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks vs placebo i.v. plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | Overall survival | NCT00519285 |

| mTOR (angiogenesis) | Temsirolimus | II | Single-arm trial: temsirolimus 25 mg i.v. every 1 week, plus anti-androgen upon progression (post-docetaxel) | Change in circulating tumor cell counts over time | NCT00887640 |

| Everolimus | II | Single-arm trial: everolimus 10 mg orally daily plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | Objective response rate | NCT00459186 | |

| II | Single-arm trial: everolimus 5 mg orally daily plus carboplatin AUC =5 i.v. every 3 weeks (post-docetaxel) | Time to disease progression | NCT01051570 | ||

| Ridaforolimus | II | Single-arm trial: ridaforolimus 50 mg i.v. every 1 week (post-docetaxel) | Objective response rate | NCT00110188 | |

| PI3K (angiogenesis) | BKM-120 | II | Single-agent trial: BKM-120 100 mg orally daily (post-docetaxel) | Progression-free survival | Being planned |

| S100A9 (angiogenesis) | Tasquinimod | III | Randomized trial: tasquinimod 1 mg orally daily vs placebo daily (pre-docetaxel) | Progression-free survival | NCT01234311 |

| Clusterin (apoptosis) | Custirsen | III | Randomized trial: custirsen 640 mg i.v. every 1 week plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks vs docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | Overall survival | NCT01188187 |

| III | Randomized trial: custirsen 640 mg i.v. every 1 week plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks vs placebo i.v. every 1 week plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (post-docetaxel) | Improvement in pain | NCT01083615 | ||

| Survivin (apoptosis) | YM-155 | II | Single-arm trial: YM-155 5 mg/m2 i.v. daily over 7 days (post-docetaxel) | ≥50% PSA ↓ | NCT00257478 |

| II | Single-arm trial: YM-155 5 mg/m2 i.v. daily over 7 days plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | Objective response rate | NCT00514267 | ||

| LY2181308 | II | Randomized trial: LY2181308 750 mg i.v. every 1 week plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks vs docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | Progression-free survival | NCT00642018 | |

| IGF-1R (cell nutrition) | Cixutumumab | II | Randomized trial: cixutumumab 6 mg/kg i.v. every 1 week plus mitoxantrone 12 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks vs ramucirumab (see above) 6 mg/kg i.v. every 1 week plus mitoxantrone 12 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (post-docetaxel) | Progression-free survival | NCT00683475 |

| II | Single-arm study: cixutumumab 6 mg/kg i.v. every 1 week plus temsirolimus 25 mg i.v. every 1 week | Time to disease progression | NCT01026623 | ||

| Figitumumab | II | Single arm trial: figitumumab 20 mg/kg i.v. every 3 weeks plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre- and post-docetaxel) | Objective response rate | NCT00313781 | |

| Src kinase (bone regulation) | Dasatinib | III | Randomized trial: dasatinib 100 mg orally daily plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks vs placebo orally daily plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (pre-docetaxel) | Overall survival | NCT00744497 |

| Saracatinib | II | Randomized trial: saracatinib 175 mg orally daily vs zoledronate 4 mg i.v. every 4 weeks (pre- or post-docetaxel) | Change in bone resorption parameters | NCT00558272 | |

| KX2-391 | II | Single-arm trial: KX2-391 40 mg orally twice daily (pre-docetaxel) | Time to disease progression | NCT01074138 | |

| HDAC (epigenetics) | Panobinostat | II | Single-arm trial: panobinostat 15 mg/m2 i.v. on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle (post-docetaxel) | Progression-free survival | NCT00667862 |

| DNMT (epigenetics) | Azacitidine | II | Single-arm study: azacitidine 150 mg/m2 i.v. on days 1–5 of a 21-day cycle plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 i.v. every 3 weeks (post-docetaxel) | Objective response rate | NCT00503984 |

| PARP (DNA repair) | Olaparib | II | Single-arm study: olaparib 400 mg orally twice daily (pre- or post-docetaxel) | Objective response rate | NCT01078662 |

| Veliparib | II | Single-arm study: veliparib 40 mg orally twice daily on days 1–7 of a 28-day cycle plus temozolomide 150 mg/m2 orally on days 1–5 of a 28-day cycle (post-docetaxel) | ≥30% PSA ↓ | NCT01085422 | |

Abbreviations: AR, androgen receptor; AUC, area under the curve; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4; CYP17; cytochrome P450 17; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor receptor-1; i.v., intravenous; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; VEGF-R, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

MDV3100

A slightly different AR-directed approach has focused on the development of second-generation anti-androgens that have advantages over the previous agents in this class (bicalutamide, nilutamide and flutamide). One such drug is MDV3100, an oral non-steroidal AR antagonist with a binding affinity for the AR, which is five times greater than that of bicalutamide.6 Importantly, MDV3100 remains a potent antagonist of the AR in the castration-resistant state, even in the setting of over-expressed or constitutively activated AR.7 In addition, unlike other anti-androgens that may also function as partial AR agonists, MDV3100 does not exhibit any measurable agonistic activity. Finally, MDV3100 reduces translocation of the AR from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, blocking binding of the AR to androgen-response elements of DNA, with resultant tumoricidal activity as opposed to the cytostatic activity that first-generation anti-androgens exhibit in these model systems8 (Figure 1). Notably, recent studies have shown the emergence of ligand-independent AR splice variants in CRPC, some of which may also be inhibited by MDV3100.7

A phase I/II study of oral MDV3100 in men with chemotherapy-naïve (n =65) or taxane-pretreated (n =75) metastatic CRPC has been published recently.9 In that trial, ≥50% PSA declines were seen in 62 and 51% of chemotherapy-naïve and taxane-pretreated patients, objective tumor responses were observed in 36 and 12% of men and improvements in 18F-dihydrotestosterone positron emission tomography imaging were noted in 67 and 40% of men. Radiographic progression-free survival was 6.7 months in the docetaxel-pretreated patients and >17 months in chemotherapy-naïve patients. In addition, 49% of all patients with unfavorable baseline circulating tumor cell (CTC) levels (≥5 cells per 7.5 ml of whole blood) converted to favorable CTC counts (<5 cells) after MDV3100 treatment (including 75% of pre-chemotherapy patients and 37% of post-chemotherapy patients).9 Side effects of MDV3100 are generally mild, and include fatigue (27%) and nausea (9%). Rare seizures (3/140 patients) have also been reported, perhaps mediated by a direct effect of AR antagonism on central nervous system γ-aminobutyric acid-A receptors.10

A pivotal placebo-controlled double-blind phase III study (AFFIRM), randomizing 1170 patients with docetaxel-pretreated ketoconazole-naïve CRPC to receive either MDV3100 160 mg daily (n =780) or placebo (n =390), has now completed accrual (Table 1). This trial has been powered to detect a 25% overall survival improvement with the use of MDV3100 compared with placebo. A second randomized phase III trial (PREVAIL) investigating the same treatment arms in men with chemotherapy-naïve CRPC is currently underway, and has also been powered to detect a clinically relevant survival improvement. If confirmed, these results may suggest that more potent inhibitors of AR transcriptional activity may result in significant clinical benefits, even in men who were deemed to be refractory to hormonal manipulations. In addition, one advantage of MDV3100 over agents such as abiraterone or orteronel is the lack of a need for concurrent corticosteroid administration. However, the optimal sequencing of this agent, if approved, with immunotherapies and other emerging hormonal therapies will need to be defined through future clinical trials.

Emerging AR-directed agents

Men with CRPC will inevitably develop disease progression despite treatment with abiraterone/orteronel or MDV3100. Possible resistance mechanisms to these agents include further (second) mutations in the AR gene, truncated or alternatively spliced AR transcripts, constitutively activated AR, androgen synthesis by CYP17-independent pathways and genetic changes in the CYP17A gene preventing its inhibition by abiraterone/orteronel.11 To overcome such resistance mechanisms and to produce sustained inhibition of AR-dependent signaling, CYP17 inhibitors and second-generation anti-androgens may have to be used in combination with each other (or with additional targeted agents such as those discussed below), more potent analogs of both agents may have to be developed such as inhibitors of the N-terminal transcriptional activation domain of AR12 or agents with dual CYP17-inhibitory and AR-blocking properties may have to be identified.

To this end, TOK-001 is a novel oral agent with structural similarity to abiraterone.13 However, in addition to inducing potent CYP17 (C17,20-lyase) inhibition, this compound has AR antagonistic activity and also causes downregulation of AR protein expression14 (Figure 1). TOK-001 is currently being evaluated in a phase I/II clinical trial (ARMOR1) in men with metastatic chemotherapy-naïve CRPC who have not received previous ketoconazole (Table 1).

Finally, ARN-509 is a novel oral antiandrogen that is a structural analog of MDV3100 optimized for sensitivity to prostate cancers with overexpressed AR, and showing greater potency and efficacy than MDV3100 in preclinical experiments15 (Figure 1). ARN-509 is now being studied in a phase I/II clinical trial allowing enrollment of three CRPC populations: men without previous docetaxel or abiraterone treatment, men with previous abiraterone treatment and men with previous docetaxel treatment (Table 1). Additional therapeutic options indirectly targeting AR include inhibitors of tyrosine kinases that can directly activate AR signaling (for example, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), Src kinase, G-protein-coupled receptors), inhibitors of chaperone proteins (for example, heat-shock protein 90) and epigenetic agents that may reduce AR transcriptional levels. Thus, additional AR-directed therapies are on the horizon and entering the clinic using a variety of approaches.

Immune checkpoint blockade in metastatic CRPC

The autologous cellular immunotherapy, sipuleucel-T, has been discussed previously in the first review of this two-part series. This review will outline an alternative immune-directed strategy: inhibition of immunological checkpoints.

Ipilimumab

Owing to ongoing host immunological pressures on evolving tumors, cancers have developed several mechanisms to escape immune surveillance, effectively inducing a relative state of immune tolerance.16 One way to inhibit immunological evasion by tumor cells is through blockade of the immune checkpoint molecule cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) using monoclonal antibodies. CTLA-4 is a cell surface protein found on tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes that functions as a negative regulator of T-cell activation, leading to attenuation of antitumor T-cell responses.17 In murine prostate cancer models, CTLA-4 inhibition has previously been shown to potentiate T-cell effects and induce tumor rejection as well as reduce metastatic recurrence after primary prostate tumor resection,18 providing evidence that immune checkpoint blockade may be a useful approach.

Several clinical trials using the anti-CTLA-4 antibody, ipilimumab, have been conducted in men with meta-static CRPC. These include phase I and II studies of ipilimumab monotherapy or in combination with radiation,19,20 as well as a phase I dose-escalating study combining ipilimumab with granulocyte–macrophage-colony-stimulating factor.21 Encouragingly, ≥50% PSA reductions were observed in about 20% of patients and radiological tumor responses were seen in about 5% of men. Another phase I study testing the combination of ipilimumab with a granulocyte–macrophage-colony-stimulating factor-secreting allogeneic cellular prostate cancer immunotherapy (GVAX) also showed ≥50% PSA responses (in 33% of men) and a few objective clinical responses (8% of men) at upper dose levels.22 These results are particularly worth noting, because bonafide PSA and tumor responses were rarely reported in the immunotherapy trials discussed in the previous review (for example, using sipuleucel-T or Prostvac-VF). Common side effects of ipilimumab include fatigue (42%), nausea (35%), pruritus (24%), constipation (21%) and rash (19%). In addition, because in a normal host CTLA-4 serves to attenuate autoimmunity, immunological toxicities resulting from an unchecked and overly exuberant immune response may occur. Such severe immune-related adverse events include autoimmune colitis (8%), adrenal insufficiency (2%), hepatitis (1%), and even hypophysitis (1%).23

To investigate the effect of ipilimumab on overall survival, a multicenter placebo-controlled randomized phase III study in docetaxel-refractory CRPC has been launched, which aims to examine the combination of ipilimumab and radiation therapy in men with bone metastases (Table 1). A total of 800 patients will first receive palliative radiation therapy to a bone lesion, and will then be randomized (1:1) to intravenous ipilimumab or placebo infusion given every 3 weeks. This trial is somewhat innovative in that it incorporates low-dose radiotherapy before immunotherapy in an effort to prime an antitumor immune response against all sites of metastatic disease through release of antigen from irradiated tumor cells. A second double-blind randomized phase III study comparing ipilimumab monotherapy against placebo in 600 patients with chemotherapy-naïve metastatic CRPC is now underway, and has also been powered to detect an overall survival improvement with ipilimumab (Table 1).

Encouragingly, a phase III trial in patients with metastatic melanoma has recently shown a survival advantage with the use of ipilimumab,24 providing a proof of principle that CTLA-4 blockade may have merit in human cancers and resulting in the Food and Drug Administration approval of this agent for metastatic melanoma. Thus, CTLA-4 blockade and other immune checkpoint blockades (such as PD-1 antagonism)25 are emerging as potential therapeutic strategies in CRPC, in which the overall risk–benefit ratio of induced auto-immunity vs antitumor activity will need to be evaluated carefully in the context of controlled clinical trials in these men who are generally older and more heavily pre-treated than melanoma patients.

Alternative targeted approaches for metastatic CRPC

Although AR-dependent signaling almost always occurs in CRPC, there can be substantial heterogeneity in the intensity of this AR signaling.26 Prostate cancers with lower AR activity or those exposed to prolonged periods of androgen suppression may show upregulation of other oncogenic pathways, including Src kinase, cluster-in, epithelial–mesenchymal transition pathways, PI3K, c-MET and others. Numerous drugs inhibiting alternative pathways that have crosstalk with AR-dependent pathways have been evaluated in clinical trials. Here, we will focus on selected promising agents that are currently being investigated in phase II and III studies (Figure 1).

Apoptosis

Clusterin is a stress-induced antiapoptotic chaperone protein expressed in various cancers including prostate cancer,27 and has received renewed attention due to the development of an antisense inhibitor to this protein. Importantly, expression of clusterin in prostate tumors increases after treatment with androgen ablation or chemotherapy,28,29 conferring a more resistant phenotype. Custirsen is a novel intravenously administered antisense oligonucleotide moiety that inhibits clusterin at the mRNA level (Figure 1), increasing sensitivity to androgen deprivation as well as chemotherapy in prostate cancer cell lines and xenograft models.30,31

In a randomized phase II study of docetaxel with or without custirsen in 82 patients with metastatic CRPC, PSA responses (58 vs 54%) as well as progression-free survival (7.3 vs 6.1 months) were similar in both arms. However, overall survival trended in favor of the combination arm (23.8 vs 16.9 months, P =0.06), although survival was not the primary end point of this study and confidence intervals around these estimates were wide and potentially confounded by subsequent therapies.32 Adverse events associated with custirsen included fatigue (>80%), fever (30–50%), rigors (40–60%), diarrhea (40–60%) and rash (20–40%). Another phase II study of second-line chemotherapy plus custirsen in patients with docetaxel-pretreated CRPC has recently completed accrual, and survival outcomes are awaited. Finally, a registrational placebo-controlled phase III study of docetaxel retreatment with or without custirsen for the second-line management of men with docetaxel-refractory disease was recently launched (Table 1); overall survival was chosen as the primary end point in this trial. However, the recent approval of cabazitaxel and changing standards of care call into question the value of docetaxel retreatment in all but a select group of men in this setting.

Another class of drugs mediating their effect via the apoptotic pathway is the survivin antagonists. Survivin, one of the most cancer-specific proteins ever identified, has been shown to inhibit apoptosis as well as to enhance cell proliferation and promote tumor angiogenesis in multiple tumor types including prostate cancer.33 Because of its marked upregulation in malignant tissues but not in normal cells, and the observation that its suppression leads to inhibition of tumor growth, survivin has attracted attention as a promising target for anticancer therapies.

Two agents in this class are currently in clinical development. The first is LY-2181308 (an antisense oligonucleotide that binds to survivin mRNA)34 and the second is YM-155 (a small-molecule survivin inhibitor).35 Several phase II studies investigating these two drugs in men with metastatic CRPC are now underway or have recently completed accrual (Table 1).

Src kinase signaling

Src is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase signal-transduction protein that is important in tumor cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, survival and transition to the castration-resistant state.36 Src also controls normal and abnormal osteoclastic activity, and has been implicated in development and progression of bone metastases.37 Dasatinib is an oral inhibitor of multiple oncogenic kinases including Src. In experimental models, dasatinib suppressed proliferation of prostate cancer cell lines,38 and inhibited adhesion, migration and invasion.39 In addition, dasatinib reduced tumor growth and lymph node involvement in a prostate cancer mouse xenograft model.40 A phase II study of single-agent dasatinib in men with metastatic CRPC did not show significant PSA responses, but 19% of patients were free of disease progression at 6 months. In addition, more than half of subjects had ≥40% declines in urinary N-telopeptide levels (a marker of bone resorption), and 60% showed reductions in bone alkaline phosphatase.41 In a separate phase I/II study combining dasatinib with docetaxel in a similar patient population, PSA responses were observed in 57% of participants, objective radiographic responses were seen in 60% of men and 30% of patients with bone metastases showed amelioration in bone scans.42 A large placebo-controlled randomized phase III study evaluating this combination in 1500 men with metastatic chemotherapy-naïve CRPC is now underway (Table 1), and will examine overall survival as its primary end point. Adverse effects of dasatinib include diarrhea (62%), nausea (47%), fatigue (45%) and fluid retention (21%). Newer Src kinase inhibitors, such as saracatinib43 and KX2-391,44 are in earlier stages of clinical development in patients with metastatic CRPC (Table 1).

Angiogenesis

Tumor angiogenesis is thought to have an important role in prostate cancer maintenance and progression, and elevated plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been correlated with advanced clinical stage and decreased survival.45 In addition, antibodies to VEGF slow tumor proliferation in prostate cancer xenograft models, especially when combined with chemotherapy.46 However, despite strong preclinical rationale, a phase III randomized study in men with chemotherapy-untreated CRPC (CALGB 90401) failed to show a survival advantage with the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab when combined with docetaxel compared with docetaxel used alone (22.6 vs 21.5 months), although significant improvements were seen with respect to PSA responses (70 vs 58%) and radiographic responses (53 vs 42%), as well as progression-free survival (9.9 vs 7.5 months).47 However, these results do not indicate that antiangiogenic therapies may never have a role in the treatment of CRPC, as much of this failure may be explained by an imbalance of treatment-related toxicities (cardiovascular events, neutropenic complications) in this older population with multiple co-morbidities. To this end, it was reported that the presence and number of co-morbidities (for example, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, liver disease) among patients in the CALGB 90401 trial significantly correlated with survival, and that there was an increase in the average number of co-morbidities in the docetaxel–bevacizumab arm.48 Future development of this and other antiangiogenic agents may rely on combinations with other classes of angiogenesis inhibitors or other chemotherapeutic drugs whose toxicities do not overlap, and will require careful patient selection for those men most likely to benefit and not be harmed by this class of agents.

An alternative approach has focused on tyrosine kinase inhibitors, agents that block angiogenic transmembrane receptors such as the VEGF receptor (VEGFR) (Figure 1). In phase II studies involving men with metastatic CRPC, oral sorafenib was shown to prevent radiological progression and even caused regression of bone metastases in some patients (<10%), but did not induce significant PSA responses.49,50 Similarly, oral sunitinib produced some partial radiographic responses (~10%), but had minimal effect on PSA levels in men with both chemotherapy-naïve and docetaxel-pretreated CRPC.51,52 In addition, a single-arm study of docetaxel plus sunitinib showed tolerability and a reasonable degree of clinical activity in the front-line setting (39% objective response rate), with over 90% of men surviving 1 year.53 However, a definitive randomized phase III study comparing single-agent sunitinib vs placebo in patients with docetaxel-refractory disease completed accrual of over 800 patients, and was found not to confer an overall survival improvement.54 This result suggests that single-agent anti-VEGFR- or platelet-derived growth factor receptor-based therapies may be insufficient to promote clinical benefit. Importantly, exploring the activity of these VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitors in combination with established cytotoxic and immune-modulatory or hormonal therapies remains of great interest, given the potential for synergy when combining these agents. Finally, a novel oral VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, cediranib,55 is currently being tested in a phase II study where it is being administered with or without the Src inhibitor dasatinib in patients with metastatic docetaxel-refractory CRPC (Table 1). Adverse events related to the use of these tyrosine kinase inhibitors include fatigue (30–50%), nausea (20–40%), hypertension (15–25%), diarrhea (30–50%), hand–foot syndrome (20–30%), rash (25–40%) and congestive heart failure (rare).

Another target that has received recent attention is the MET protein, a transmembrane receptor whose only known ligand is hepatocyte growth factor. Aberrant activation or overexpression of MET is a common event in prostate cancer (especially in castration-resistant bone metastases), and is associated with proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis.56,57 Moreover, androgen suppression has been shown to induce increased MET expression.58 Cabozantinib (XL184) is an oral potent inhibitor of MET and VEGFR that has shown robust antiangiogenic, antiproliferative and anti-invasive activity in preclinical systems.59 Preliminary results from a phase II study in men with metastatic CRPC with up to one previous chemotherapy revealed objective responses in 10% of patients with measurable soft-tissue disease, and improvements in bone scans in a remarkable 95% of men with osseous metastases, which was often accompanied by pain improvements.60 Toxicities with this agent include fatigue (67%), diarrhea (55%), anorexia (51%), emesis (44%) and hypertension (22%). Although the 12-week success rates, particularly in the bone, are strikingly high (including some complete resolutions of skeletal abnormalities as visualized on bone scan), the lack of robust PSA responses and the uncertainty over the durability of these results as measured by progression-free survival will require confirmatory controlled trials to assess the overall clinical benefit of this agent as well as the appropriate dose for long-term use. As the prostate cancer landscape is changing rapidly, the evaluation of cabozantinib in the post-cabazitaxel and post-abiraterone setting against prednisone or best supportive care would be one such approach to the rapid evaluation of clinical benefit of this novel dual MET/VEGFR2 inhibitor. Further investigation of this agent’s activity in the bone using novel imaging techniques (18F-positron emission tomography) or pharmacodynamic studies should also be considered to further understand how this agent is controlling metastatic disease.

A final angiogenesis-inhibiting agent that has received renewed attention is the oral quinoline derivative tasquinimod (Table 1). Although the antiangiogenic properties of this agent have been amply shown in several in vitro and in vivo prostate cancer models,61 the exact mechanism of action of this drug remains elusive and appears to be unrelated to VEGFR inhibition. However, one proposed action of tasquinimod involves inhibition of S100A9, a calcium-binding protein involved in cell cycle progression and differentiation as well as recruitment of tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells.62 Impressively, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase II study involving 200 patients with chemotherapy-naïve metastatic CRPC met its primary end point and showed that patients receiving oral tasquinimod had a median progression-free survival of 7.6 vs 3.2 months in those receiving placebo (P =0.001).63 Adverse events with this agent included gastrointestinal disorders (40%), fatigue (23%), musculoskeletal pain (12%) and asymptomatic elevations of pancreatic enzymes and inflammatory markers. Rare but serious toxicities were heart failure (1%), myocardial infarction (1%), stroke (1%) and deep vein thrombosis (4%). A multi-center randomized phase III trial of tasquinimod vs placebo in patients with chemotherapy-untreated metastatic CRPC has been launched.

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway

Given the high prevalence of phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN) loss and PI3K pathway activation in metastatic prostate cancer, the development of agents that target components of this important oncogenic survival pathway has focused initially on men with metastatic CRPC.64 One critical component has been the TORC1 pathway, an important gatekeeper protein that regulates extracellular and nutrient-based signaling with the metabolic programs and energy outputs of many cells including malignant prostate cancer cells.65 Although mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR or TORC1) inhibitors may have modest single-agent activity in advanced CRPC,66,67 the combination of these drugs with docetaxel is attractive given their ability to reverse or delay chemotherapy resistance in prostate cancer cell lines.68,69 In addition, these agents induce apoptosis when combined with chemotherapy in patients who have activation of the Akt pathway as a result of PTEN mutation/loss or other genetic alteration.70 Limitations of the use of single-agent TORC1 inhibitors have included feedback upregulation of upstream survival signals (such as PI3K and growth factor receptor levels) as well as the lack of induction of apoptosis or prolonged cytostasis owing to parallel activation of alternate oncogenic pathways.67,71,72

Several mTOR inhibitors have entered human clinical testing in combination with other agents (Figure 1). One of these, everolimus, is currently being evaluated in combination with docetaxel for the first-line treatment of metastatic CRPC,73 and is also being used in combination with carboplatin for the treatment of docetaxel-refractory disease (Table 1). In addition, temsirolimus and everolimus are being tested in combination with anti-androgen therapy in men with chemotherapy-naïve CRPC (based on preclinical studies showing synergistic activity of anti-androgens with mTOR inhibitors),74,75 and also as maintenance therapy after responding to docetaxel treatment.76 A third mTOR inhibitor, ridaforolimus, is also being investigated in the phase II setting as monotherapy in men with taxane-refractory CRPC (Table 1). Toxicities of mTOR agents include maculopapular rash (20–40%), hypertriglyceridemia (40–70%), hyperglycemia (30–60%), allergic reactions (3–5%), pedal edema (15–30%), mucositis (40–60%), pneumonitis (5–10%) and thrombocytopenia (20–40%).

An alternative strategy focuses on directly inhibiting proximal mediators of the mTOR pathway, such as PI3K or Akt. To this end, advanced prostate cancers frequently show activation of PI3K and Akt,77,78 and this activation has correlated with recurrent disease following prosta-tectomy.79 In addition to promoting cell survival through the inhibition of apoptosis, the PI3K/Akt pathway regulates cell growth, proliferation and angiogenesis via mTOR, and facilitates translation of signals such as c-Myc, hypoxia-inducible factor, cyclin D and VEGF.80 Interestingly, PI3K may also contribute to stemness in prostate cancer, leading to accelerated tumor-initiating potential and invasiveness, as well as resistance to current therapies.81 Given this preclinical data, there are a number of agents entering the clinic with activity against the PI3K/ Akt pathway that are now being tested in men with CRPC. A detailed discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this review, and a number of excellent recent reviews have been published on this topic.64,82

BKM-120 is an oral pan-PI3K inhibitor that lacks direct mTOR kinase inhibitory effects83 (Figure 1). A phase II study using BKM-120 in men with docetaxel-refractory metastatic CRPC will soon be launched (Table 1) through the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Consortium to investigate the clinical activity of PI3K inhibition in this disease as well as potential pharmacodynamic predictors of benefit. Other PI3K, dual PI3K-TORC1/2 and Akt inhibitors are also in early stages (phases I and II) of drug development in CRPC and other solid tumors.64 Toxicities of these agents have included hyperglycemia (20–40%), rash (10–20%), mood changes (10–20%) and fatigue (20–30%).83,84 The development of strategies to identify pretreatment biomarkers (that is, from tumor specimens, specialized imaging or CTCs) that may predict which men are likely to benefit from PI3K inhibitors will be essential in the rational development of these agents.

Insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 pathway

Insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 (IGF-1R) and its ligands may have an important role in prostate carcino-genesis through mechanisms that involve mitogenesis, antiapoptosis and cellular transformation (Figure 1). Moreover, IGF-1R is often overexpressed in prostate tumors and can mediate cell proliferation and resistance to androgen ablation.85,86 Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies that bind to the extracellular domain of IGF-1R can potently inhibit the function of this receptor. In prostate cancer cell lines and in xenograft models, such antibodies have been shown to inhibit growth of both androgen-dependent and -independent tumors.87,88

Cixutumumab is an intravenous fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that specifically targets IGF-1R, inhibiting ligand binding and IGF signaling.89 In a phase II study of cixutumumab in men with metastatic CRPC, 29% of patients showed stable disease for 6 months, whereas a similar percentage experienced PSA responses.90 Toxicities with this agent included fatigue (20–30%), hyperglycemia (15–25%), thrombocytopenia (10–20%), hyperkalemia (5–10%) and muscle spasms (10–20%). A phase II study combining cixutumumab with mitoxantrone compared with ramucirumab (an anti-VEGFR2 monoclonal antibody) with mitoxantrone in men with docetaxel-refractory metastatic CRPC has completed accrual and results are anticipated soon (Table 1).

Figitumumab is a second fully human anti-IGF-1R immunoglobulin G2 monoclonal antibody that has entered clinical testing.91 In a phase Ib study of intravenous figitumumab given in combination with docetaxel to men with metastatic CRPC, 22% of patients had objective tumor responses and 67% had disease stabilization lasting ≥6 months.92 In addition, 90% of patients with measurable CTC levels at baseline achieved ≥30% reductions in CTC counts after treatment. Toxicities of this combination regimen were leucopenia (including neutropenia) (20%), fatigue (50%), diarrhea (25%) and hyperglycemia (10%). A randomized phase II study of figitumumab combined with docetaxel in men with chemotherapy-naïve (arm A) and docetaxel-refractory (arm B) CRPC has completed accrual and results are awaited (Table 1).

Epigenetic therapies

Histone deacetylases are regulators of histone acetylation status, which is critical for androgen receptor-mediated transcriptional activation of genes governing cell survival, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis93 (Figure 1). Vorinostat is an oral histone deacetylase inhibitor that has shown antitumor activity in prostate cancer cell lines as well as animal models.94 However, a phase II study of vorinostat monotherapy in men with docetaxel-refractory CRPC did not show significant PSA or radiological responses and was associated with a high frequency of adverse events including fatigue (80%), emesis (75%), diarrhea (35%) and weight loss (25%).95 A second histone deacetylase inhibitor, panobinostat (used both as an oral and intravenous agent), has completed phase I testing in combination with docetaxel;96,97 the intravenous formulation has been chosen for future development. Side effects of panobinostat include nausea (75%), diarrhea (50%), thrombocytopenia (50%) and fatigue (38%). A phase II trial of single-agent IV panobinostat in docetaxel-refractory disease is currently ongoing (Table 1).

DNA methylation of important tumor suppressor genes represents another epigenetic mechanism by which prostate cancer may progresses to a castration-resistant state.98 The hypomethylating agent azacitidine (Figure 1) is a subcutaneously administered drug that exerts its antineoplastic effects by inhibiting DNA methyltransferases in promoter regions of genes, leading to reversal of gene silencing.99 In preclinical prostate cancer models, azacitidine reverses resistance to androgen ablation and chemotherapy,100 making this agent attractive for clinical trial development. To this end, a phase II study of azacitidine in men with chemotherapy-naïve CRPC induced lengthening of PSA doubling times in 56% of patients and resulted in a median progression-free survival time of 12.4 weeks.101 Toxicities of azacitidine included fatigue (41%) and neutropenia (18%). Another phase II study evaluating the combination of docetaxel and azacitidine in men with docetaxel-pretreated CRPC is now underway (Table 1).

PARP inhibition

PARPs are a family of enzymes that mend single-strand DNA breaks through the repair of base excisions (Figure 1). PARP inhibition leads to accumulation of single-strand DNA breaks that, if left unchecked, lead to double-strand DNA breaks at replication forks.102 These double-strand breaks are repaired by homologous recombination, mediated in part by the tumor suppressor proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2. Preclinical studies have shown that BRCA1/2 mutation combined with PARP inhibition creates a ‘synthetic lethality’ for such cells.103 This results in exquisite sensitivity of BRCA1/2 mutant cells to PARP inhibitors. Another group of tumors that show increased sensitivity to PARP inhibition are those that harbor PTEN loss, a frequent phenomenon in CRPC. To this end, PTEN-null tumors exhibit genomic instability due to downregulation of Rad51 and impaired homologous recombination, or due to defects in cell cycle checkpoints.104

Olaparib was the first PARP inhibitor to reach human clinical testing (Figure 1). In a phase I study of oral olaparib in patients with BRCA1/2-mutated tumors, this agent produced notable responses in several subjects including a >50% PSA drop with resolution of bone metastases in a man with BRCA2-related CRPC.105 Toxicities of olaparib include gastrointestinal disturbance (40%), fatigue/somnolence (30%), lymphopenia (5%) and thrombocytopenia (5%). A larger phase II study of olaparib in patients with advanced BRCA1/2-mutated cancers is ongoing (Table 1). However, the success of PARP inhibitors in CRPC patients will rely on the identification of biomarkers of sensitivity to these agents outside of the traditional germline BRCA1/2 mutations, including PTEN loss or somatic or alternative genetic or epigenetic alterations in DNA repair enzymes.

Another important property of PARP inhibitors is their ability to enhance the activity of DNA-damaging cytotoxic agents (for example, alkylators, platinum compounds and topoisomerase inhibitors).106 To this end, addition of the PARP inhibitor veliparib (ABT-888) to temozolomide potentiates the antineoplastic effects of the alkylating agent in several cancer cell lines and animal xenograft models.107 This has provided the rationale for conducting a single-arm phase II study examining the combination of oral veliparib and oral temozolomide in men with metastatic CRPC who have progressed after 1–2 previous chemotherapies (Table 1). Adverse events with veliparib are minimal, and no dose-limiting toxicities were reported in phase I trials. Finally, a randomized phase II cooperative group trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without veliparib in the second-line treatment of metastatic CRPC is being planned.

Conclusion

With more drugs at our fingertips for the treatment of metastatic CRPC than ever before, and an increasing number of novel therapeutic targets being discovered every day, we are still left with several challenges and unanswered questions. First, we must determine how these approved and experimental therapies should ideally be sequenced in individual patients with CRPC. For example, should sipuleucel-T routinely be given before chemotherapy? Should abiraterone be reserved only for docetaxel-refractory patients? Second, we will need to develop strategies to optimally combine these drugs in a rational manner, taking advantage of our understanding of negative feedback loops and alternative pathway activation to overcome resistance to monotherapies. For instance, should mTOR inhibitors always be combined with IGF pathway inhibitors, or should PARP inhibitors only be used together with DNA-damaging chemotherapies? In addition, can PTEN loss predict benefit from PI3K or PARP inhibitors? Ultimately, only prospective trials incorporating biomarker-driven hypotheses will be able to address these important clinical questions. Thus, the collection of tumor specimens or correlative samples may be essential in identifying novel targets or developing enrichment strategies for future study of these agents.

Third, we must design smarter trials with the aim of quickly yet reliably identifying agents that do not hold promise, while enabling those that do to move swiftly to registrational studies. For example, in the clinical development of MDV3100, a pivotal phase III trial was designed directly following an initial phase I/II study that showed significant drug activity in men with CRPC. Finally, we must select our patients more carefully based on clinical or molecular characteristics, to identify the subset most likely to benefit from a particular therapy. For example, in men with significant pain, perhaps sipuleucel-T is not appropriate systemic therapy given the prolonged onset of action and lack of palliative benefits; in addition, immune-based biomarkers may shed light on which men may obtain a greater degree of benefit from these immunotherapies. However, despite these and other unresolved issues, continued advances in our understanding of prostate cancer biology and genomics will certainly further expand our armamentarium of treatment options for patients with CRPC moving forward. Although the future looks bright, we must continue to combine good science with innovative drug development strategies to successfully chart this course.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Dr Antonarakis declares no conflicts of interest. Dr Armstrong has served as a consultant for Novartis and Amgen; he is on the speakers bureau for Pfizer/ Wyeth, Dendreon, and sanofi-aventis; and he has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Imclone, Pfizer/Wyeth, Active Biotech, Medivation, Dendreon, Novartis and sanofi-aventis.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsunaga N, Kaku T, Ojida A, Tanaka T, Hara T, Yamaoka M, et al. C(17,20)-lyase inhibitors: design, synthesis and structure–activity relationships of (2-naphthylmethyl)-1H-imidazoles as novel C(17,20)-lyase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:4313–4336. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasaitis TS, Bruno RD, Njar VC. CYP17 inhibitors for prostate cancer therapy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.11.005. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreicer R, Agus DB, MacVicar GR, Wang J, MacLean D, Stadler WM. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of TAK-700 in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase I/II, open-label study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract 3084. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Clegg NJ, Scher HI. Anti-androgens and androgen-depleting therapies in prostate cancer: new agents for an established target. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:981–991. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70229-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson PA, Chen YF, Balbas MD, Wongvipat J, Socci ND, Viale A, et al. Constitutively active androgen receptor splice variants expressed in castration-resistant prostate cancer require full-length androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16759–16765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, Anand A, Taplin ME, Efstathiou E, et al. Antitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1–2 study. Lancet. 2010;375:1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster WR, Car BD, Shi H, Levesque PC, Obermeier MT, Gan J, et al. Drug safety is a barrier to the discovery and development of new androgen receptor antagonists. Prostate. 2011;71:480–488. doi: 10.1002/pros.21263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attard G, Cooper CS, de Bono JS. Steroid hormone receptors in prostate cancer: a hard habit to break? Cancer Cell. 2009;16:458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadar MD. Small molecule inhibitors targeting the ‘Achilles heel’ of androgen receptor activity. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1208–1213. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN_10-3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handratta VD, Vasaitis TS, Njar VC, Gediya LK, Kataria R, Chopra P, et al. Novel C-17-heteroaryl steroidal CYP17 inhibitors/antiandrogens: synthesis, in vitro biological activity, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor activity in the LAPC4 human prostate cancer xenograft model. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2972–2984. doi: 10.1021/jm040202w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasaitis T, Belosay A, Schayowitz A, Khandelwal A, Chopra P, Gediya LK, et al. Androgen receptor inactivation contributes to antitumor efficacy of 17{alpha}-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase inhibitor 3beta-hydroxy-17-(1H-benzimidazole-1-yl)androsta-5, 16-diene in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2348–2357. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawyers CL. New insights into the prostate cancer genome and therapeutic implications. Proceedings of the Prostate Cancer Foundation Annual Scientific Retreat; Washington, DC. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drake CG, Jaffee E, Pardoll DM. Mechanisms of immune evasion by tumors. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:51–81. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodi FS. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5238–5242. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon ED, Foster BA, Hurwitz AA, Madias C, Allison JP, Greenberg NM, et al. Elimination of residual metastatic prostate cancer after surgery and adjunctive cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) blockade immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15074–15079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Small EJ, Tchekmedyian NS, Rini BI, Fong L, Lowy I, Allison JP. A pilot trial of CTLA-4 blockade with human anti-CTLA-4 in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1810–1815. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beer TM, Slovin SF, Higano CS, Tejwani S, Dorff TB, Stankevichet E, et al. Phase I trial of ipilimumab alone and in combination with radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(Suppl):abstract 5004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fong L, Kwek SS, O’Brien S, Kavanagh B, McNeel DG, Weinberg V, et al. Potentiating endogenous antitumor immunity to prostate cancer through combination immunotherapy with CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF. Cancer Res. 2009;69:609–615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerritsen W, van den Eertwegh AJ, de Gruijl T, van den Berg HP, Scheper RJ, Sackset N, et al. Expanded phase I combination trial of GVAX immunotherapy for prostate cancer and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(Suppl):abstract 5146. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillard T, Yedinak CG, Alumkal J, Fleseriu M. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody therapy associated autoimmune hypophysitis: serious immune related adverse events across a spectrum of cancer subtypes. Pituitary. 2010;13:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s11102-009-0193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendiratta P, Mostaghel E, Guinney J, Tewari AK, Porrello A, Barry WT, et al. Genomic strategy for targeting therapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2022–2029. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoubeidi A, Chi K, Gleave M. Targeting the cytoprotective chaperone, clusterin, for treatment of advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1088–1093. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyake H, Nelson C, Rennie PS, Gleave ME. Acquisition of chemoresistant phenotype by overexpression of the antiapop-totic gene testosterone-repressed prostate message-2 in prostate cancer xenograft models. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2547–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.July LV, Akbari M, Zellweger T, Jones EC, Goldenberg SL, Gleave ME. Clusterin expression is significantly enhanced in prostate cancer cells following androgen withdrawal therapy. Prostate. 2002;50:179–188. doi: 10.1002/pros.10047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gleave M, Miyake H. Use of antisense oligonucleotides targeting the cytoprotective gene, clusterin, to enhance androgen- and chemo-sensitivity in prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2005;23 :38–46. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sowery RD, Hadaschik BA, So AI, Zoubeidi A, Fazli L, Hurtado-Coll A, et al. Clusterin knockdown using the antisense oligonucleotide OGX-011 resensitizes docetaxel-refractory prostate cancer PC-3 cells to chemotherapy. BJU Int. 2008;102:389–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chi KN, Hotte SJ, Yu EY, Tu D, Eigl BJ, Tannock I, et al. Randomized phase II study of docetaxel and prednisone with or without OGX-011 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4247–4254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan BM, O’Donovan N, Duffy MJ. Survivin: a new target for anti-cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talbot DC, Ranson M, Davies J, Lahn M, Callies S, André V, et al. Tumor survivin is downregulated by the antisense oligonucleotide LY2181308: a proof-of-concept, first-in-human dose study. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6150–6158. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satoh T, Okamoto I, Miyazaki M, Morinaga R, Tsuya A, Hasegawa Y, et al. Phase I study of YM155, a novel survivin suppressant, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3872–3880. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wheeler DL, Iida M, Dunn EF. The role of Src in solid tumors. Oncologist. 2009;14:667–678. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Araujo J, Logothetis C. Targeting Src signaling in metastatic bone disease. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lombardo LJ, Lee FY, Chen P, Norris D, Barrish JC, Behnia K, et al. Discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methyl-phenyl)-2-(6-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazin-1-yl)-2-methylpyrimidin-4-ylami-no)thiazole-5-carboxamide, a dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor with potent antitumor activity in preclinical assays. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6658–6661. doi: 10.1021/jm049486a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam S, Kim D, Cheng JQ, Zhang S, Lee JH, Buettner R, et al. Action of the Src family kinase inhibitor, dasatinib (BMS-354825), on human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9185–9189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park SI, Zhang J, Phillips KA, Araujo JC, Najjar AM, Volgin AY, et al. Targeting Src family kinases inhibits growth and lymph node metastases of prostate cancer in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3323–3333. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu EY, Wilding G, Posadas E, Gross M, Culine S, Massard C, et al. Phase II study of dasatinib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7421–7428. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Araujo J, Mathew P, Armstrong AJ, Braud EL, Posadas E, Lonberg M, et al. Dasatinib combined with docetaxel for castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from a phase 1/2 study. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26204. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lara PN, Jr, Longmate J, Evans CP, Quinn DI, Twardowski P, Chatta G, et al. A phase II trial of the Src-kinase inhibitor AZD0530 in patients with advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer: a California Cancer Consortium study. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:179–184. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328325a867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adjei AA, Cohen RB, Kurzrock R, Gordon GS, Hangauer D, Dyster L, et al. Results of a phase I trial of KX2-391, a novel non-ATP competitive substrate-pocket directed Src inhibitor, in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl):abstract 3511. [Google Scholar]

- 45.George DJ, Halabi S, Shepard TF, Vogelzang NJ, Hayes DF, Small EJ, et al. Prognostic significance of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor levels in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer treated on Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9480. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1932–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sweeney P, Karashima T, Kim SJ, Kedar D, Mian B, Huang S, et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 antibody reduces tumorigenicity and metastasis in orthotopic prostate cancer xenografts via induction of endothelial cell apoptosis and reduction of endothelial cell matrix metalloproteinase type 9 production. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2714–2724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelly WK, Halabi S, Carducci MA, George DJ, Mahoney JF, Stadler WM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel, prednisone, and placebo with docetaxel, prednisone, and bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: survival results of CALGB 90401. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract LBA4511. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halabi S, Kelly WK, George DJ, Morris MJ, Kaplan EB, Small EJ. Comorbidities predict overall survival in men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl):abstract 189. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahut WL, Scripture C, Posadas E, Jain L, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, et al. A phase II clinical trial of sorafenib in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:209–214. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aragon-Ching JB, Jain L, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Wright JJ, Steinberg SM, et al. Final analysis of a phase II trial using sorafenib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2009;103:1636–1640. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dror Michaelson M, Regan MM, Oh WK, Kaufman DS, Olivier K, Michaelson SZ, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib in men with advanced prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:913–920. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sonpavde G, Periman PO, Bernold D, Weckstein D, Fleming MT, Galsky MD, et al. Sunitinib malate for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer following docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:319–324. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zurita AJ, Liu G, Hutson T, Kozloff M, Shore N, Wilding G, et al. Sunitinib in combination with docetaxel and prednisone in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl):abstract 5166. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfizer Inc. [accessed date 3 October 2011];Pfizer discontinues phase 3 trial of sunitinib in advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer. (press release 9/ 27/2010). http://www.pfizer.com/news/press_releases/pfizer_press_release_archive.jsp#guid=discontinue_phase_3_trial_sutent_092710&source=RSS_2010&page=4.

- 55.Ryan CJ, Stadler WM, Roth B, Hutcheon D, Conry S, Puchalski T, et al. Phase I dose escalation and pharmacokinetic study of AZD2171, an inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in patients with hormone refractory prostate cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25 :445–451. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9050-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knudsen BS, Gmyrek GA, Inra J, Scherr DS, Vaughan ED, Nanus DM, et al. High expression of the Met receptor in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Urology. 2002;60:1113–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Christensen JG, Burrows J, Salgia R. c-Met as a target for human cancer and characterization of inhibitors for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Lett. 2005;225:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verras M, Lee J, Xue H, Li TH, Wang Y, Sun Z. The androgen receptor negatively regulates the expression of c-Met: implications for a novel mechanism of prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:967–975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shojaei F, Lee JH, Simmons BH, Wong A, Esparza CO, Plumlee PA, et al. HGF/c-Met acts as an alternative angiogenic pathway in sunitinib-resistant tumors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10090–10100. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith DC, Spira A, De Greve J, Hart H, Holbrechts S, Lin CC, et al. Phase 2 study of XL184 in a cohort of patients with castration resistant prostate cancer and measurable soft tissue disease. Proceedings of the Annual EORTC Conference; Berlin, Germany. 2010; p. abstract 406. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isaacs JT, Pili R, Qian DZ, Dalrymple SL, Garrison JB, Kyprianou N, et al. Identification of ABR-215050 as lead second generation quinoline-3-carboxamide anti-angiogenic agent for the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2006;66:1768–1778. doi: 10.1002/pros.20509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Björk P, Björk A, Vogl T, Stenström M, Liberg D, Olsson A, et al. Identification of human S100A9 as a novel target for treatment of autoimmune disease via their binding to quinoline carboxamides. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e97. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pili R, Haggman M, Stadler WM, Gingrich JR, Assikis VJ, Bjork A, et al. A randomized, multicenter, international phase II study of tasquinimod in chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract 4510. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sarker D, Reid AH, Yap TA, de Bono JS. Targeting the PI3K/ AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4799–4805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amato RJ, Jac J, Mohammad T, Saxena S. Pilot study of rapamycin in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2008;6:97–102. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2008.n.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Armstrong AJ, Netto GJ, Rudek MA, Halabi S, Wood DP, Creel PA, et al. A pharmacodynamic study of rapamycin in men with intermediate- to high-risk localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3057–3066. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu L, Birle DC, Tannock IF. Effects of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor CCI-779 used alone or with chemotherapy on human prostate cancer cells and xenografts. Cancer Res. 2005;65 :2825–2831. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morgan TM, Pitts TE, Gross TS, Poliachik SL, Vessella RL, Corey E. RAD001 (everolimus) inhibits growth of prostate cancer in the bone and the inhibitory effects are increased by combination with docetaxel and zoledronic acid. Prostate. 2008;68 :861–871. doi: 10.1002/pros.20752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thomas G, Speicher L, Reiter R, Ranganathan S, Hudes G, Strahs A, et al. Demonstration that temsirolimus preferentially inhibits the mTOR pathway in the tumors of prostate cancer patients with PTEN deficiencies. Proceedings of AACR-NCI-EORTC Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics; Philadelphia, PA. 2005; p. abstract C131. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun SY, Rosenberg LM, Wang X, Zhou Z, Yue P, Fu H, et al. Activation of Akt and eIF4E survival pathways by rapamycin-mediated mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7052–7058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O’Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ross RW, Manola J, Oh WK, Ryan C, Kim J, Rastarhuyeva I, et al. Phase I trial of RAD001 and docetaxel in castration-resistant prostate cancer with FDG-PET assessment of RAD001 activity. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(Suppl):abstract 5069. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang W, Zhu J, Efferson CL, Ware C, Tammam J, Angagaw M, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth progression by antiandrogens and mTOR inhibitor in a PTEN-deficient mouse model of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7466–7472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Armstrong AJ, Kemeny G, Turnbull JD, Chao C, Winters C, Fesko YA, et al. Impact of temsirolimus and anti-androgen therapy on circulating tumor cell5(CTC) biology in men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer (CRPC): a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract TPS249. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Emmenegger U, Sridhar SS, Booth CM, Kerbel R, Berry SR, Ko Y. A phase II study of maintenance therapy with temsirolimus after response to first-line docetaxel chemotherapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract TPS246. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shukla S, Maclennan GT, Hartman DJ, Fu P, Resnick MI, Gupta S. Activation of PI3K-Akt signaling pathway promotes prostate cancer cell invasion. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1424–1432. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sun X, Huang J, Homma T, Kita D, Klocker H, Schafer G, et al. Genetic alterations in the PI3K pathway in prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:1739–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bedolla R, Prihoda TJ, Kreisberg JI, Malik SN, Krishnegowda NK, Troyer DA, et al. Determining risk of biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer by immunohistochemical detection of PTEN expression and Akt activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3860–3867. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gera JF, Mellinghoff IK, Shi Y, Rettig MB, Tran C, Hsu JH, et al. Akt activity determines sensitivity to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors by regulating cyclin D1 and c-Myc expression. J Biol. 2004;279:2737–2746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dubrovska A, Kim S, Salamone RJ, Walker JR, Maira SM, García-Echeverría C, et al. The role of PTEN/Akt/PI3K signaling in the maintenance and viability of prostate cancer stem-like cell populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:268–273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810956106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Courtney KD, Corcoran RB, Engelman JA. The PI3K pathway as drug target in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1075–1083. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baselga J, De Jonge MJ, Rodon J, Burris HA, Birle DC, De Buck SS, et al. A first-in-human phase I study of BKM120, an oral pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract 3003. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burris H, Rodon J, Sharma S, Herbst RS, Tabernero J, Infante JR, et al. First-in-human phase I study of the oral PI3K inhibitor BEZ235 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstract 3005. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chan JM, Stampfer MJ, Ma J, Gann P, Gaziano JM, Pollak M, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF binding protein-3 as predictors of advanced stage prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1099–1106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.14.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krueckl SL, Sikes RA, Edlund NM, Bell RH, Hurtado-Coll A, Fazli L, et al. Increased insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor expression and signaling are components of androgen-independent progression in a lineage-derived prostate cancer progression model. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8620–8629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu JD, Odman A, Higgins LM, Haugk K, Vessella R, Ludwig DL, et al. In vivo effects of the human type-1 insulin-like growth factor receptor antibody A12 on androgen-dependent and androgen-independent xenograft human prostate tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3065–3074. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Plymate SR, Haugk K, Coleman I, Woodke L, Vessella R, Nelson P, et al. An antibody targeting the type-1 insulin-like growth factor receptor enhances the castration-induced response in androgen-dependent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6429–6439. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rowinsky EK, Youssoufian H, Tonra JR, Solomon P, Burtrum D, Ludwig DL. IMC-A12, a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13 :5549–5555. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Higano C, Alumkal J, Ryan CJ, Yu EY, Beer TM, Chandrawansa K, et al. A phase II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of single-agent IMC-A12, a monoclonal antibody against the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-IR), as monotherapy in patients with metastastic, asymptomatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl):abstract 5142. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gualberto A. Figitumumab (CP-751,871) for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:575–585. doi: 10.1517/14712591003689980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Molife LR, Fong PC, Paccagnella L, Reid AH, Shaw HM, Vidal L, et al. The insulin-like growth factor-I receptor inhibitor figitumumab (CP-751,871) in combination with docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumours: results of a phase Ib dose-escalation, open-label study. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:332–339. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nakayama T, Watanabe M, Suzuki H, Toyota M, Sekita N, Hirokawa Y, et al. Epigenetic regulation of androgen receptor gene expression in human prostate cancers. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1789–1796. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Welsbie DS, Xu J, Chen Y, Borsu L, Scher HI, Rosen N, et al. Histone deacetylases are required for androgen receptor function in hormone-sensitive and castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:958–966. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bradley D, Rathkopf D, Dunn R, Stadler WM, Liu G, Smith DC, et al. Vorinostat in advanced prostate cancer patients progressing on prior chemotherapy (NCI Trial 6862): trial results and interleukin-6 analysis: a study by the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Clinical Trial Consortium and University of Chicago Phase 2 Consortium. Cancer. 2009;115:5541–5549. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rathkopf DE, Chi KN, Vaishampayan U, Hotte US, Vogelzang N, Alumkal J, et al. Phase Ib dose finding trial of intravenous panobinostat with docetaxel in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl):abstract 5064. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rathkopf D, Wong BY, Ross RW, Anand A, Tanaka E, Woo MM, et al. A phase I study of oral panobinostat alone and in combination with docetaxel in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:181–189. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]