Abstract

Importance of the field

Prostate cancer is the mostly commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in males. The culmination of the last 70 years of clinical drug development has documented that androgen ablation plus taxane-based systemic chemotherapy enhances survival, but is not curative, in metastatic prostate cancer. To effect curative therapy, additional drugs must be developed that enhance the response when combined with androgen ablation/taxane therapy.

Areas covered in this review

The history of the discovery and development of tasquinimod as a second-generation oral quinoline-3-carboxamide analogue for prostate cancer will be presented.

What the reader will gain

The mechanism for such anticancer efficacy is via tasquinimod’s ability to inhibit the ‘angiogenic switch’ within cancer sites required for their continuous lethal growth.

Take home message

Tasquinimod is a novel inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis that enhances the therapeutic anticancer response when combined with other standard-of-care modalities (radiation, androgen ablation, and/or taxane-based chemotherapies) in experimental animal models, but does not inhibit normal wound healing. It has successfully completed clinical Phase II testing in humans and will shortly enter registration Phase III evaluation for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer.

Keywords: antiangiogenic agent, prostate cancer, quinoline-3-carboxamide, tasquinimod

1. Introduction: the magnitude of the problem with prostate cancer

As men age, prostate cancer becomes amore frightening and recurrent nightmare. Presently, it is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in males of the industrialized nations of the world. In the US alone, there will be 200,000 new cases diagnosed each year; this year alone, 30,000 men will die of metastatic prostate cancer, even with aggressive systemic therapy [1]. This is despite more than 70 years of knowledge that metastatic prostate cancers characteristically require a physiologically normal level of circulating androgen for their continued growth and are therefore responsive to androgen ablation therapy [2]. In fact, the use of oral estrogen (diethylstilbestrol) to suppress serum androgen was the first successful systemic therapy ever developed for a human malignancy [2].

Due to the side effects of oral estrogen, long-acting luteinizing hormone release hormone (LHRH) peptide analogues were developed in the 1980s and 1990s; these also suppress serum androgen, and are now the standard of care for androgen ablation [2]. Over the last decade, the use of taxane-based systemic therapies was documented to enhance survival when combined with androgen ablation [3]. Unfortunately, however, while androgen ablation plus taxane-based systemic chemotherapy enhances survival, it is still not curative for metastatic prostate cancer.

Based upon these facts, the diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer still remains a death warrant unless the man dies of intercurrent disease. Thus, there is a profound and urgent need for the development of additional drugs which, when combined with androgen ablation/taxane therapies, can prevent death from metastatic prostate cancer.

2. Discovery that quinoline-3-carboxamide analogs are therapeutically active compounds

This review will summarize the history of the discovery and clinical development of the quinoline-3-carboxamide analogue, tasquinimod (Box 1) for the treatment of prostate cancer. This will provide an informative paradigm of how drug development occurs in the present world of biomedical research. This history involves a 30-year process of critical collaborative research involving industry and academia. Tasquinimod’s development has required sequential financial support and involvement of industry personnel from five separate companies, combined with a score of academic researchers. As will be highlighted in this review, it has not been a simple linear process for tasquinimod from drug discovery involving target validation, small molecule identification, and preclinical proof of concept to clinical drug development. In fact, to borrow a phrase from the famous British knight, Sir Paul McCartney, it has been a ‘long and winding road’ for tasquinimod as a second-generation quinoline-3-carboxamide analogue; but it is finally entering clinical Phase III registration trials.

Box 1. Drug summary.

| Drug name | Tasquinimod |

| Phase | Phase II |

| Indication | Prostate cancer |

| Pharmacology description | Angiogenesis inhibitor |

| Route of administration | Alimentary, p.o. |

| Chemical structure |  |

| Pivotal trial(s) | Clinical Phase I/II trials in patients with progressing castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer have been completed. Active Biotech is initiating clinical Phase III registration trials in patients with progressing castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer orally given 1 mg tasquinimod per day. |

Pharmaprojects – copyright to Citeline Drug Intelligence (an Informa business). Readers are referred to Informa-Pipeline (http://informa-pipeline.citeline.com) and Citeline (http://informa.citeline.com).

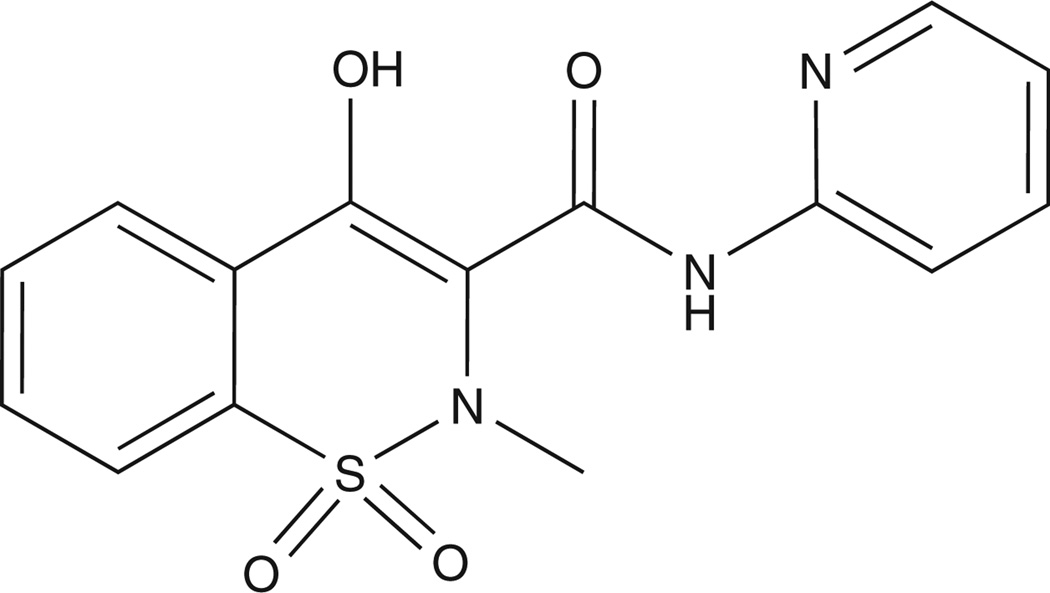

Tasquinimod’s long and winding road starts in the early 1980s, when Torbjorn Stalhandske, leading a research program at the AB Leo Research Laboratories in Helsingborg, Sweden, focused on identifying small-molecule inhibitors of inflammation based upon the NSAID, piroxicam (Figure 1), as the lead platform. Out of this program came the identification of a series of quinoline-3-carboxamide analogues which, instead of inhibiting, stimulated carrageenan-induced inflammatory responses [4]. The Leo group was insightful for not discarding the discovery that while these analogues are not anti-inflammatory, they might be efficacious for other therapeutic uses. The lead quinoline-3-carboxamide analogue (LS 2616) identified by this drug development program was given the generic name roquinimex (Figure 2), and later the registered trade mark name linomide. The Leo group initially documented that delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) is suppressed in rats bearing dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA)-induced autonomous breast cancers and that oral treatment with roquinimex restored the DTH response and inhibited the growth of these autonomous breast cancers. In addition, oral roquinimex inhibited by 50% the development of lung metastasis in rats inoculated with syngeneic Lewis lung carcinoma cells [4].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of piroxicam [CAS number 36322-90-4; (8E)-8-[hydroxy-(pyridin-2-ylamino)methylidene]-9-methyl-10,10-dioxo-10λ6-thia-9-azabicyclo[4.4.0] deca-1,3,5-trien-7-one].

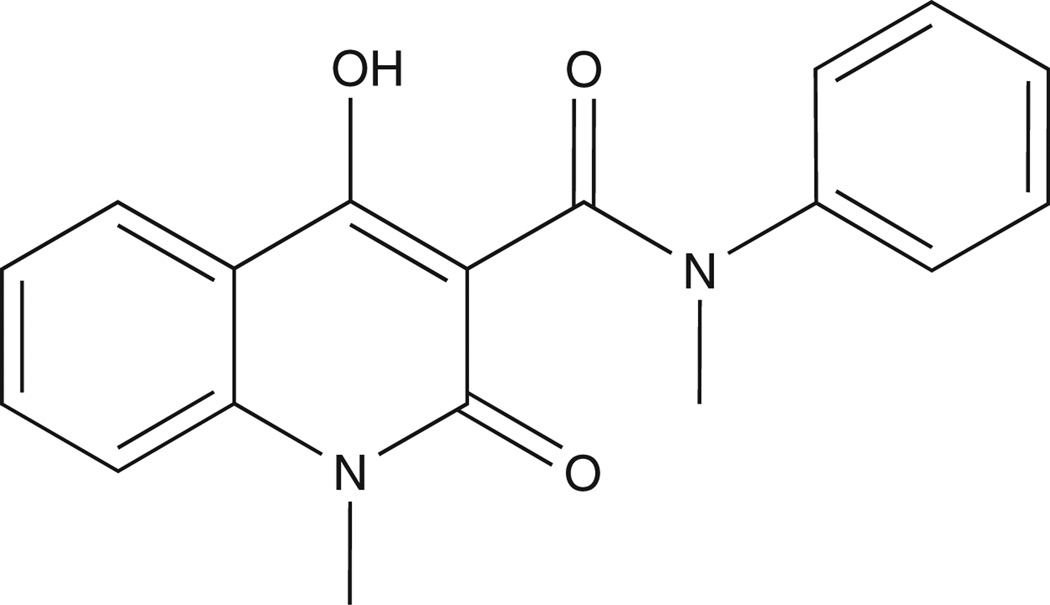

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of roquinimex [LS-2616; CAS number 84088-42-6; 4-hydroxy-N, 1-dimethyl-2-oxo-N-phenyl-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide].

In follow-up studies to identify the mechanism for such anticancer efficacy, Terje Kalland at the University of Lund, collaborating with the Leo group, reported in 1985 that oral roquinimex increases NK cell activity in mice [5]. In 1986, Kalland, using the B16 mouse melanoma model, confirmed that daily oral roquinimex inhibited the growth and metastasis of this cancer in mice and that this anticancer response is mediated by both NK as well as non-NK effects [6]. Based upon these preclinical proof-of-principle results, AB Leo initiated drug development and began clinical Phase I trials with oral roquinimex [7]. In that same year, two papers from Stalhandske and colleagues reported that in addition to its anticancer efficacy, roquinimex inhibits autoimmunity in mice [8, 9]. This latter discovery would have a profound effect upon the subsequent dual clinical development of roquinimex for both cancer and non-cancer autoimmune diseases.

In 1986, AB Leo was purchased by Pharmacia AB, with the latter company continuing the clinical development of roquinimex. In 1988, Bo Nilsson reported on the initial Phase I clinical results for roquinimex in humans [7]. In 1990, Pharmacia-LEO merged with Kabi to become Kabi-Pharmacia, which built a new research facility in Lund, Sweden and continued their support of roquinimex development.

3. Discovery that roquinimex is therapeutic for prostate cancer

After the US National Cancer Act of 1971, in which President Richard Nixon ‘declared war on cancer’, the National Prostate Cancer Project (NPCP) was created based at Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, New York, with Gerald Murphy as its initial leader. The NPCP built upon the validation by Charles Huggins in the early 1940s that prostate cancer, like the normal prostate from which it is derived, almost universally retains responsiveness to surgical- or estrogen-induced androgen ablation therapy. Between 1970 and 1988, when the program ended, the NPCP completed a series of clinical trials comparing the efficacy against advanced metastatic prostate cancer of a large variety of hormonal and chemotherapy combinations, with most of the later being cytotoxic agents [2].

These studies took advantage of the development in the early 1980s and FDA approval in 1985 of LHRH analogues as effective alternatives to surgical castration or estrogen hormonal therapy [2]. In addition to supporting clinical trials, the NPCP also supported biomarker and drug discovery activities, mostly within academic laboratories. These studies lead to the discovery of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as a biomarker for disease progression, and to its FDA approval in 1986 for monitoring prostate cancer progression [2].

My own early career development was dependent upon such NPCP support. During this period, it became frustratingly clear that within an individual patient, prostate cancer cells are characteristically heterogeneous with regard to their sensitivity to killing by antiandrogen, cytotoxic, or radiation monotherapies, and that such tumor cell heterogeneity is inevitable due to the inherent genetic instability of these malignant cells [10]. Within an individual patient, such tumor cell heterogeneity results in the presence of prostate cancer cells that are castration-sensitive as well as malignant cells that are castration-resistant, thus preventing cures based upon androgen ablation monotherapy, no matter how complete [2, 3, 11]. This heterogeneity also explains why even multicycle regimens with single cytotoxic agents are not curative for such castration-resistant patients [3].

By 1989, my laboratory focused upon the development of multicycle/combinational chemo/hormonal therapies using a series of appropriate in vivo rodent prostate cancer models. Many of the approaches tested involved the combinational use of chronic androgen ablation therapy plus episodic cycles of cytotoxic agents. While these combinational approaches were effective in inhibiting the growth of these model prostate cancers, they also suppressed the host immune system and decreased blood cell counts, restricting the interval between when additional cycles of cytotoxic agent could be given without unacceptable host toxicity. These studies also demonstrated that if the interval between chemotherapy cycles is too prolonged, then these multicycle/combinational approaches lost their efficacy [12]. These experimental results identified the need for an agent that would inhibit tumor growth without suppressing -- perhaps even stimulating -- the immune system and blood cell counts, which could be given during the interval when additional cytotoxic agents could not be given.

Based upon the published reports that daily oral roquinimex treatment stimulates the immune system [4, 5] and has anticancer efficacy in multiple animal models [4, 6, 13], this raised the possibility that combining daily oral roquinimex with intermittent cycles of cytotoxic chemotherapy might be a more curative approach for prostate cancer. To test this possibility, my laboratory at Johns Hopkins began collaboration in 1991 with Beryl Hartley-Asp of Kabi Pharmacia. These initial studies by Tomohiko Ichikawa and co-workers documented that as a single agent, roquinimex treatment robustly and consistently inhibited the in vivo growth and metastases of a series of rodent prostate cancer models without suppressing the immune system or decreasing blood cell numbers; for maximal anticancer efficacy, roquinimex had to be given daily [14].

Additional studies documented that this antitumor effect was produced in both immune-competent and T-cell--deficient nude rats, and that depletion of NK cells did not prevent the therapeutic response to roquinimex in rats [14]. These studies were followed up by the work of Jasminka Vukanovic and colleagues, which discovered that the mechanism for these anticancer effects against prostate cancers is roquinimex’s ability to block tumor angiogenesis and thus decrease the tumor blood flow [15]. In the early 1990s, Judah Folkman championed the then novel concept that cancer cells go through an initial avascular growth phase, but that such cancers cannot continue to grow and be lethal unless they undergo a ‘vascular switch’ by which they acquire the ability to simulate tumor angiogenesis [16]. Thus the discovery that roquinimex is a potent oral active tumor antiangiogenic agent was highly novel in 1993.

In 1994, collaborative studies between Kabi Pharmacia and an independent academic group confirmed our discovery that daily oral roquinimex is an active antiangiogenic agent in a hamster model [17] alone. In addition, another independent academic group documented in 1994 that such daily oral roquinimex treatment does not inhibit, but rather stimulates, wound healing in a rat model [18]. The next year, roquinimex’s efficacy to inhibit cancer growth and metastases via its antiangiogenic ability was reconfirmed using a Lewis lung carcinoma model in mice [19]. These results, combined with the previous rat and hamster data, document that roquinimex’s antiangiogenic ability is not species-specific but a general phenomenon.

That same year, Vukanovic and co-workers documented that the anticancer and antimetastatic responses to roquinimex in rats are associated with a decrease in tumor-infiltrating macrophages and that roquinimex inhibits the ability of rat macrophages to secrete TNF-α, a known angiogenic stimulator [20], confirming earlier mouse studies [21]. These studies also documented that antitumor, antimetastatic, and antimacrophage effects of roquinimex are unaffected by NK cell depletion in vivo [20]. Additionally that year, we demonstrated that human prostate cancer cells growing as xenografts in nude mice are sensitive to apoptotic death induced in vivo by the antiangiogenic effects of roquinimex [22].

4. Clinical trials with roquinimex

Based upon the hypothesis that roquinimex is immunomodulatory and the fact that roquinimex had completed Phase I testing, two clinical trials with the drug were begin in 1991. The first was a pilot clinical trial in acute myeloid leukemia patients treated with a combination of autologous bone marrow transplantation and oral roquinimex at 0.35 mg/kg body weight per week [23]. In the second study, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) in collaboration with Kabi Pharmacia initiated a 72-patient Phase II trial in advanced renal cancer of roquinimex given orally twice weekly at 5 mg during the first week with dose escalation to 10 mg during the second week and 15 mg thereafter [24]. At the given dose and schedule, roquinimex was well tolerated, but had limited antitumor activity against metastatic renal cancer [24]. This study was followed by a second EORTC Phase II study of daily oral roquinimex 10 mg in 35 metastatic renal cancer patients with good prognostic factors [25]. Roquinimex at this dose and schedule was poorly tolerated, with 17% of the patients being withdrawn and 23% having dose reduction due to adverse events, mostly flu-like symptoms of myalgia, arthralgia, and fatigue. Several cases of pericarditis and neuropathy were observed.

In 1993, two different academic groups in collaboration with Kabi Pharmacia published two papers documenting roquinimex’s therapeutic abilities in non-cancer applications, which would significantly affect the course of the future clinical development of roquinimex. The first paper documented that roquinimex prevents death in four different experimental mouse models of septic shock and that this protection involves its ability to inhibit macrophage secretion of TNF-α [21]. The second publication documented that roquinimex is therapeutic in a mouse chronic relapsing–experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [EAE], an animal model for MS [26].

The year 1995 was a turning-point in the course of clinical development of roquinimex, for two reasons. First, Kabi Pharmacia and Upjohn merged to form Pharmacia & Upjohn in that year. Second, based upon the previous preclinical data implicating TNF-α in MS and the demonstration that roquinimex inhibits both TNF-α secretion by macrophages [20, 21] and progression in the EAE mouse model [26], the new company sponsored two small (30 and 31 patients each, respectively) double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II clinical trials using monthly MRI scans to test the efficacy of daily oral roquinimex (at doses of 2.5 mg/day) in secondary progressive MS over a 6-month treatment period. The first trial was by the academic team of Karussis and colleagues at Hadassah University in Israel [27]; the second was by the academic team of Andersen and co-workers at the University of Goteborg, Sweden [28]. The conclusion of these Phase II MS studies, both reported in 1996, was that the drug ‘tends to inhibit the progression of the disease’ [27].

These Phase II results led Pharmacia & Upjohn to sponsor two large (> 700 MS patients each), multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multidose Phase III registration trials, one in North America and the other in Europe and Australia [29, 30]. For the North American study, patients were randomized into a placebo or one of three treatment arms receiving daily oral roquinimex at 1, 2.5, or 5 mg/day; in the European/Australian study, patients received placebo or one of two oral treatment arms given 2.5 or 5 mg/day [29, 30]. For both studies, the intended treatment period was to be 2 years. Randomization for both trials was completed in 1997, but both had to be prematurely terminated in 1997 due to unanticipated serious cardiopulmonary toxicities including pericarditis, pleural effusion, myocardial infarction, and death [29, 30]. Based on these toxicities, roquinimex was never tested in clinical trials with prostate cancer patients.

5. Discovery and development of second-generation quinoline-3-carboxamide analogue

When Pharmacia merged with Upjohn in 1995, its Lund research facility was threatened with closure. This was when Active Biotech AB bought both the Lund facility and its research portfolio, including the quinoline-3-carboxamide platform. Between 1996 and 1998, multiple laboratories – including ours – documented the therapeutic potential of roquinimex as a cancer drug in a variety of experimental systems. These studies documented that roquinimex could: i) inhibit the in vivo development of prostate and breast cancers in rodents [31]; ii) suppress in vitro endothelial cell growth and migration stimulated by VEGF [32] and inhibit VEGF-induced angiogenesis and growth of human breast cancer cells when inoculated as xenografts in nude mice [33]; and iii) synergistically inhibit growth of rat prostate cancers in vivo when combined with androgen ablation [34], due to the ability of androgen ablation to suppress VEGF secretion by the cancer cells combined with roquinimex’s ability to inhibit angiogenic response to the suppressed levels of VEGF [35]. While this growing body of preclinical science suggested that roquinimex could be a useful agent against prostate and breast cancer, the results of the clinical Phase II trials against advanced renal cancer were published reporting that when given orally at 10 mg/day, roquinimex was too toxic [25]. This toxicity was also observed in the MS clinical trials, even when the oral dosing was reduced to only 1 mg/day.

These toxicity results reinvigorated Active Biotech’s overall R&D efforts, headed by Tomas Leanderson in the new millennium. As part of this overall effort, a program of screening the chemical library of quinoline-3-carboxamide analogues synthesized by the Active Biotech medicinal chemistry group led by Anders Bjork was initiated to identify second-generation compounds lacking the pro-inflammatory side effects of roquinimex for the treatment of both MS and prostate cancer. These studies documented that the pro-inflammatory activity of roquinimex is due to its demethylation at the carboxamide side-chain nitrogen, producing highly planar metabolites that are pro-inflammatory (Anders Bjork, personal communication). This metabolic conversion is due to cytochrome P450-3A4 [36].

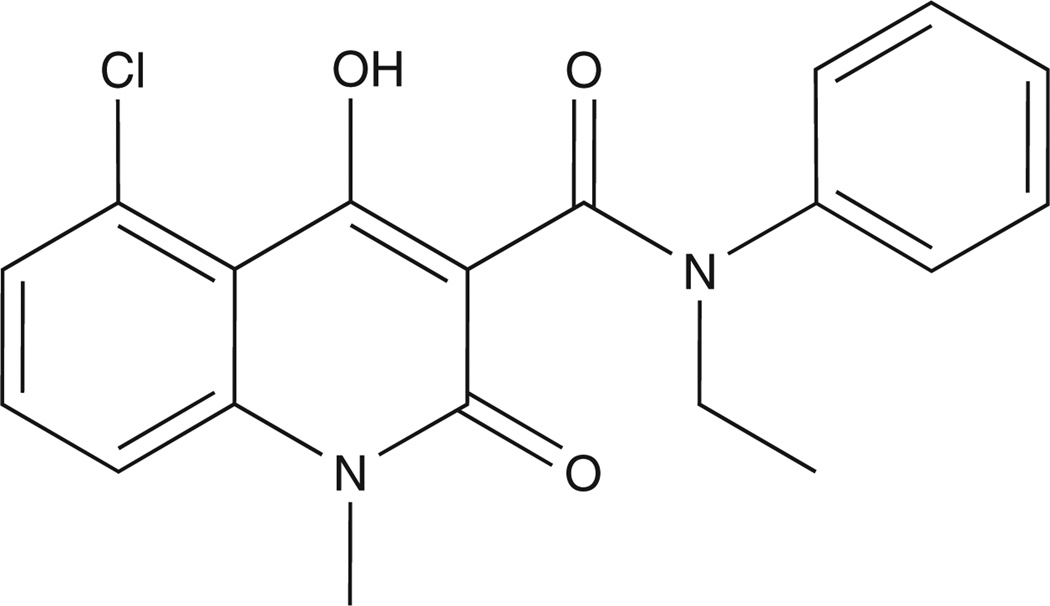

By appropriate chemical modifications, a library of second-generation quinoline-3-carboxamide analogues were synthesized that were designed to restrict the production of planar metabolites, thus highly reducing their pro-inflammatory side effects in appropriate animal models [37]. One of the molecules – given the generic name laquinimod (Figure 3) – was identified in-house by Active Biotech as the lead second-generation analogue, using a variety of animal MS models [38]. Additional preclinical structure/function studies support that autoimmune efficacy of quinoline-3-caboxamides involves their ability to bind S100A9 protein [39]. In 2004, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd incensed laquinimod from Active Biotech; it is now in clinical trials for MS [40].

Figure 3.

Chemical structure of laquinimod [ABR-215062; CAS number 248282-07-7; N-ethyl-N-phenyl-5-chloro-1,2-dihydro-4-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-oxo-3-quinoline-carboxamide].

6. Development of tasquinimod

An additional second-generation quinoline-3-carboxamide analogue with low pro-inflammatory side effects – given the name of tasquinimod (Box 1) – was identified as the lead compound for clinical development for the treatment of prostate cancer in collaborative studies between my laboratory at Hopkins and the TASQ group at Active Biotech [41–43]. This selection was based upon tasquinimod’s enhanced potency (30- to 60-fold more potent than roquinimex) and robust inhibition of in vivo growth of a large series (n = 9) of syngeneic rat and mice prostate cancers and human prostate cancer xenografts in nude mice [41–43]. Pharmacokinetic analysis following daily oral dosing documented that optimal therapeutic blood and tumor tissue levels of tasquinimod are 0.5 – 1 μM [41].

The therapeutic response to tasquinimod involves inhibition of angiogenesis, as determined by a large series of in vitro and in vivo functional assays. These assays documented that tasquinimod inhibited: i) endothelial capillary tube formation in vitro; ii) endothelial cell outgrowth from aortic rings in vitro; iii) blood vessel development in the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) of chicken eggs; iv) growth factor-induced endothelial network formation in Matrigel in vivo; v) tumor blood vessel density, real-time tumor blood flow, and tumor oxygen level measured as partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) in vivo [40]; and vi) the angiogenic switch by preventing downregulation of thrombospondin-1 and coupled upregulation of HIF-1-α and VEGF expression by prostate cancer cells [43]. In additional studies, we documented that in a series of human prostate xenografts in vivo, daily oral tasquinimod enhances the antiprostate cancer efficacy of both androgen ablation and taxotere-based therapies [42]; as well as in unpublished studies with fractionated external beam radiation. In additional unpublished structure/function studies, the group at Active Biotech documented that tasquinimod binds with nM affinity to S100A9 protein on myeloid-derived suppressor cells, decreasing their expression of VEGF and counteracting immune suppression.

Based upon its consistent ability to inhibit angiogenesis and thus cancer growth in these proof-of-concept preclinical studies, tasquinimod entered clinical Phase I testing in 2005 under the leadership of Jan Erik Damber of the University of Gothenburg. This open-label Phase I trial was unusual in that instead of treating patients with a variety of solid malignancies, all 32 of the patients in this trial had castration-resistant prostate cancer that was progressing, but they had not previously received chemotherapy. The patients received tasquinimod for up to 1 year either at fixed doses of 0.5 or 1 mg/day or an initial dose of 0.25 mg/day that was escalated to 1 mg/day. Twenty-one of the patients received tasquinimod for ≥ 4 months. The results of the Phase I trial determined that the serum half-life for tasquinimod is 40 ± 16 h and the steady-state serum level of tasquinimod produced by an oral dose of 1 mg/day of the drug is 0.5 – 1.0 μM [44]. A serum PSA decline of ≥ 50% was observed in two patients. The median to PSA progression was 19 weeks. Only 3 out of 15 patients (median time on study was 34 months) developed new bone lesions. The dose-limiting toxicity was sinus tachycardia and asymptomatic elevation in amylase. Common treatment-emergent adverse events included transient laboratory abnormalities, anemia, nausea, fatigue, myalgia, and pain.

Based upon these Phase I results, a 2:1 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind Phase II trial was initiated in 2007 comparing patients given 1 mg/day of oral tasquinimod versus placebo in 206 asymptomatic chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic, castrate-resistant prostate cancer who were progressing (determined by a rise in serum PSA, and/or a change in soft-tissue or bone sites based upon radiological scans). The trial was conducted in the US, Canada and Sweden under an Investigational New Drug application. The primary end point of the Phase II trial, led by Roberto Pili (who was initially at Hopkins, but is now at Roswell Park Cancer Institute) was to measure the proportion of patients who display disease progression after 6 months of tasquinimod therapy compared with placebo. Secondary clinical end points of importance for this group of patients included progression-free survival (PFS), safety, and effects on biomarkers.

The primary end point for this Phase II trial was a difference in the number of patients with disease progression at 6 months, and this end point was achieved [45]. The fraction of patients with disease progression during the 6-month period was 31% for patients treated with tasquinimod compared with 66% for placebo-treated patients. The median PFS was 7.6 months for the tasquinimod group, compared with 3.2 months for the placebo group (p = 0.0009). Central review of the scans support an effect on PFS with tasquinimod treatment, with a median PFS of 8.4 months for tasquinimod treated patient versus 3.8 months for the placebo patients (p = 0.0045). Subgroup analysis using the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 2 defined criteria showed that median PFS (mPFS) for patients with visceral (e.g., lung or liver) metastases was 6 months for the tasquinimod-treated group compared with 3 months for the placebo group (p = 0.0160). For patients with only bone metastases, mPFS was 12.2 for the tasquinimod versus 5.4 months for the placebo group (p = 0.0214).

Patients with soft-tissue lesions were analyzed using RECIST disease progression criteria. Tumor shrinkage was observed in 15/65 patients (23%) in the tasquinimod and 5/42 patients (12%) in the placebo group. Partial responses (tumor shrinkage of ≥ 30%) were observed in 6% of the tasquinimod-treated patients, while no objective responses (measurable responses) were observed in the placebo group [45]. Patients treated with tasquinimod had significantly decreased serum LDH levels and stabilized bone alkaline phosphatase (BAP) levels, with less pronounced effects on PSA response and progression. Serious vascular events were more common in the tasquinimod arm (myocardial infarction, heart failure or stroke [3 vs 0%]; deep vein thrombosis [4 vs 0%]). Common (> 10%) adverse events (AEs) occurring more frequently in patients receiving tasquinimod included gastrointestinal disorders, fatigue, and musculoskeletal pains, as well as asymptomatic elevation of pancreatic enzymes and pro-inflammatory markers. Grade 3 – 4 AEs (including labs) were reported in 38% of tasquinimod-treated patients.

7. Conclusions

The idea that drug development is a simple linear process is often a misconception, as exemplified by the history of tasquinimod’s development. Instead, as illustrated by tasquinimod, drug development is an iterative process requiring critical collaboration between experts in academics, industry, and regulatory agencies. The ultimate goal of such collaboration is the successful completion of clinical testing of the drug. Such clinical testing requires documenting that the drug in Phase III trials has efficacy when given as monotherapy against metastatic prostate cancer even if, ultimately, its optimal use is in combinational approaches. Tasquinimod will shortly enter this critical Phase III stage of drug development.

8. Expert opinion

For its optimal therapeutic use, an understanding of the mechanism of action of a drug is critical in order to provide a logical, as opposed to empirical, rationale for both the timing and the choice of which additional agents should be combined with the new agent. Cell and molecular biological analyses have documented that cancers must initiate an angiogenic switch in order to continuously develop an expanding tumor blood supply required for the lethal growth of the malignant cells [16]. This angiogenic switch involves the down-regulation of the expression of endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors, like thrombospondin (TSP-1), coupled with tumor hypoxia-induced upregulation of expression of angiogenesis stimulators via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1-α)–dependent transcription of VEGF and survival factors, like glucose transporter (GT)-1 [46].

While it is clear that tasquinimod’s therapeutic mechanism of action involves inhibition of the angiogenic switch within the cancer tissue, the specific molecular pathways responsible for this inhibition have not been fully elucidated. It is clear, however, that once initiated this inhibition of the angiogenic switch is associated with upregulation of TSP-1 mRNA and protein and downregulation of HIF-1-α, VEGF, and GT-1 expression within prostate cancer cells [43]. Thus, even without full knowledge of its molecular targets, it is rational to hypothesize that for optimal efficacy against metastatic prostate cancer, tasquinimod should be combined with other therapeutic approaches that either inhibit the production of angiogenic factors (VEGF by androgen ablation [35]) or increase hypoxia (radiation [47]), and/or that increase the production of antiangiogenic factors (TSP-1 by either androgen ablation [48] or taxanes [49]).

Acknowledgments

This supports research focused upon identifying the mechanism of action of tasquinimod against prostate cancer. He receives no honoraria for this research and has no stock in Active Biotech AB.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

JT Isaacs has a sponsored research agreement with Active Biotech AB overseen by the Conflict of Interest program in the Dean’s office of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Bibliography

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. A history of prostate cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:389–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basch E, Somerfeild M, Beer T, et al. Amercan Society of Clinical Oncology endorsement of the Cancer Care Ontario practice guideline on nonhormonal therapy for men with metastatic hormone-refractory (castration-resistant) prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5313–5318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stalhandske T, Eriksoo E, Sandberg B. A novel quinoline-3-carboxamide with interesting immunomodulatory activity. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1982;4:336. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalland T, Alm G, Stalhandshe T. Augmentation of mouse natural killer cell activity by LS 2616, a new immunomodulator. J Immunol. 1985;134:3956–3961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalland T. Effects of the immunomodulator LS 2616 on growth and metastasis of the murine B16-F10 melanoma. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3018–3022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson BI. Phase I study in malignancy of LS 2616, a new immunomodulator: methodological considerations. Cancer Detect Prev. 1988;12:553–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarkowski A, Gunnarsson K, Nilsson A, et al. Successful treatment of autoimmunity in MRL/1 mice with LS-2616, a new immunomodulator. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1405–1409. doi: 10.1002/art.1780291115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarkowski A, Gunnarsson K, Stalhandske T. Effects of LS-2616 administration upon the autoimmune disease of (NZB x NZW) F1 hybrid mice. Immunology. 1986;59:589–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaacs JT, Wake N, Coffey DS, et al. Genetic instability coupled to clonal selection as a mechanism for tumor progression in the Dunning R-3327 rat prostatic adenocarcinoma system. Cancer Res. 1982;42:2353–2371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaacs JT, Isaacs WB. Androgen receptor outwits prostate cancer drugs. Nat Med. 2004;10:26–27. doi: 10.1038/nm0104-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isaacs JT. Relationship between tumor size and curability of prostatic cancer by combined chemo-hormonal therapy in rats. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6290–6294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harning R, Szalay J. A treatment for metastasis of murine ocular melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:1505–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichikawa T, Lamb JC, Christensson PI, et al. The antitumor effects of the quinoline-3-carboxamide linomide on Dunning R-3327 rat prostatic cancers. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3022–3028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vukanovic J, Passaniti A, Hirata T, et al. Antiangiogenic effects of the quinoline-3-carboxamide linomide. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1833–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folkman J. The role of angiogenesis in tumor growth. Semin Cancer Biol. 1992;3:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borgstrom P, Torres Filho IP, Vajkoczy P, et al. The quinoline-3-carboxamide linomide inhibits angiogenesis in vivo. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1994;34:280–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00686033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepisto J, Laato M, Niinikoski J, et al. Stimulation of wound healing by the immunomodulator LS-2616 (Linomide) World J Surg. 1994;18:818–820. doi: 10.1007/BF00299073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borgstrom P, Torres Filho IP, Hartley-Asp B. Inhibition of angiogenesis and metastases of the Lewis-lung cell carcinoma by the quinoline-3-carboxamide, Linomide. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:719–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vukanovic J, Isaacs JT. Linomide inhibits angiogenesis, growth, metastasis, and macrophage infiltration within rat prostatic cancers. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1499–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalo JA, Gonzalez-Garcia A, Kalland T, et al. Linomide, a novel immunomodulator that prevents death in four models of septic shock. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2372–2374. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vukanovic J, Isaacs JT. Human prostatic cancer cells are sensitive to programmed (apoptotic) death induced by the antiangiogenic agent linomide. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3517–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bengtsson M, Simonsson B, Carlsson K, et al. Stimulation of NK cell, T cell, and monocyte functions by the novel immunomodulator Linomide after autologous bone marrow transplantation. A pilot study in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Transplantation. 1992;53:882–888. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199204000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pawinski A, van Oosterom AT, de Wit R, et al. An EORTC phase II study of the efficacy and safety of linomide in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:496–499. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)89028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Wit R, Pawinsky A, Stoter G, et al. EORTC phase II study of daily oral linomide in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with good prognostic factors. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:493–495. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)89027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karussis DM, Lehmann D, Slavin S, et al. Treatment of chronic-relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with the synthetic immunomodulator linomide (quinoline-3-carboxamide) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6400–6404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karussis DM, Meiner Z, Lehmann D, et al. Treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis with the immunomodulator linomide: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study with monthly magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Neurology. 1996;47:341–346. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen O, Lycke J, Tollesson PO, et al. Linomide reduces the rate of active lesions in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;47:895–900. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noseworthy JH, Wolinsky JS, Lublin FD, et al. Linomide in relapsing and secondary progressive MS: part I: trial design and clinical results. North American Linomide Investigators. Neurology. 2000;54:1726–1733. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.9.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan IL, Lycklama a Nijeholt GJ, Polman CH, et al. Linomide in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: MRI results from prematurely terminated phase-III trials. Mult Scler. 2000;6:99–104. doi: 10.1177/135245850000600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph IB, Vukanovic J, Isaacs JT. Antiangiogenic treatment with linomide as chemoprevention for prostate, seminal vesicle, and breast carcinogenesis in rodents. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3404–3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parenti A, Donnini S, Morbidelli L, et al. The effect of linomide on the migration and the proliferation of capillary endothelial cells elicited by vascular endothelial growth factor. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:619–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziche M, Donnini S, Morbidelli L, et al. Linomide blocks angiogenesis by breast carcinoma vascular endothelial growth factor transfectants. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1123–1129. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartley-Asp B, Vukanovic J, Joseph IB, et al. Anti-angiogenic treatment with linomide as adjuvant to surgical castration in experimental prostate cancer. J Urol. 1997;158:902–907. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199709000-00069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph IB, Isaacs JT. Potentiation of the antiangiogenic ability of linomide by androgen ablation involves down-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in human androgen-responsive prostatic cancers. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1054–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuvesson H, Wienkers LC, Gunnarsson PO, et al. Identification of cytochrome P4503A as the major subfamily responsible for the metabolism of roquinimex in man. Xenobiotica. 2000;30:905–914. doi: 10.1080/004982500433327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jonsson S, Andersson G, Fex T, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new 1,2-dihydro-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-3-quinolinecarboxamides for treatment of autoimmune disorders: structure-activity relationship. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2075–2088. doi: 10.1021/jm031044w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunmark C, Runstrom A, Ohlsson L, et al. The new orally active immunoregulator laquinimod (ABR-215062) effectively inhibits development and relapses of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;130:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bjork P, Bjork A, Vogl T, et al. Identification of human S100A9 as a novel target for treatment of autoimmune disease via binding to quinoline-3-carboxamides. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e97. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preiningerova J. Oral laquinimod therapy in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:985–989. doi: 10.1517/13543780903044944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isaacs JT, Pili R, Qian D, et al. Identification of ABR-215050 as lead second generation quinoline-3-carboxamide anti-angiogenic agent for the treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2006;66:1768–1778. doi: 10.1002/pros.20509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalrymple SL, Becker RE, Isaacs JT. The quinoline-3-carboxamide anti-angiogenic agent, tasquinimod, enhances the anti-prostate cancer efficacy of androgen ablation and taxotere without effecting serum PSA directly in human xenografts. Prostate. 2007;67:790–797. doi: 10.1002/pros.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsson A, Bjork A, Vallon-Christersson J, et al. Tasquinimod (ABR-215050), a quinoline-3-carboxamide anti-angiogenic agent, modulates the expression of thrombospondin-1 in human prostate tumors. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:107. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bratt O, Haggman M, Ahlgren G, et al. Open-label, clinical phase I studies of tasquinimod in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1233–1240. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pili R, Haggman M, Stadler W, et al. A randomized multicenter international phase II study of tasquinimod in chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. (abstract 4510) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:75. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moeler BJ, Dewhirst MW. Raising the bar: how HIF-1 helps determine tumor radiosensitivity. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1107–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colombel M, Filleur S, Fournier P, et al. Androgens repress the expression of the angiogenesis inhibitor thrombospondin-1 in normal and neoplastic prostate. Cancer Res. 2005;65:300–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tas F, Duranyildiz D, Soydinc HO, et al. Effect of maximum-tolerated doses and low-dose metronomic chemotherapy on serum vascular endothelial growth factor and thrombospondin-1 levels in patients with advanced no small cells lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:721–725. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]