Abstract

Background

Presence of delayed enhancement (DE) on magnetic resonance (CMR) is associated with worse clinical outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). We investigated the relationship between DE on CMR, and myocardial ischemia in HCM.

Methods and Results

HCM patients (n=47) underwent CMR for assessment of DE and vasodilator stress ammonia positron emission tomography (PET) to quantify myocardial blood flow (MBF) and coronary flow reserve (CFR). The summed difference score (SDS) for regional myocardial perfusion (rMP) was also assessed. Patients in the DE-group (n=35) had greater LV wall thickness (2.09 ± 0.44 vs. 1.78 ± 0.34 cm; P 0.03). Stress MBF (2.25 ± 0.46 vs. 1.78 ± 0.43 ml/min/g, P = 0.01), and CFR (2.78 ± 0.32 vs. 2.01 ± 0.52, P < 0.001) were significantly lower in DE-positive patients. SDS (7.3 ± 6.6 vs. 0.9 ± 1.4, P < 0.0001) was significantly higher in patients with DE. A CFR < 2.00 was seen in 18 patients (51%) with DE, but in none of the DE-negative patients (P <0.0001). CMR and PET showed visually concordant DE and rMP abnormalities in 31 patients and absence of DE and perfusion defects in 9 patients. Four DE-positive patients demonstrated normal rMP, and 3 DE-negative patients had (apical) rMP abnormalities.

Conclusions

We found a close relationship between DE by CMR and microvascular function in the majority of the patients studied. However, a small proportion of patients had DE in the absence of perfusion abnormalities, suggesting that microvascular dysfunction and ischemia are not the sole causes of DE in HCM patients.

Keywords: PET, cardiac MRI, HCM, fibrosis, ischemia

Myocardial delayed enhancement (DE) by gadolinium cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) has emerged as a highly informative biomarker with implications for diagnosis and prognosis. Case reports have shown agreement between location and quantity of myocardial fibrosis in post-mortem/explanted hearts and DE extent on ante-mortem/pre-transplant CMR, suggesting that DE could reflect fibrosis in HCM.1, 2 However, any process that increases extracellular fluid volume in the myocardium will result in DE. Hence, edema, inflammation and myocyte disarray may also result in DE.3, 4 The presence of DE on CMR has been associated with markers of sudden cardiac death,5 and higher incidence of adverse cardiovascular events, including disease progression,2, 5 heart failure symptoms,6 ventricular arrhythmias,7 and all-cause and cardiac mortality8 in HCM patients. Myocardial ischemia has been proposed as an important contributor to fibrosis in HCM.9 Abnormalities in intramural coronary arterioles coupled with increased demand by the hypertrophied myocardium can result in microvascular dysfunction, ischemia, edema, myocyte death and fibrosis in HCM patients.10, 11 However, increased transcription of pro-fibrotic genes has been detected even in the pre-hypertrophic stage of the left ventricular (LV) myocardium in transgenic mouse models of HCM, indicating that factors other than ischemia may be playing a role in the induction of fibrosis in HCM.12

Positron emission tomography (PET) is the gold standard for noninvasive quantification of myocardial perfusion and myocardial blood flow (MBF) 13 and has been shown to predict heart failure, sustained ventricular arrhythmias, and cardiovascular-related death in HCM.14, 15 Measurement of basal and vasodilator-induced MBF permits calculation of coronary flow reserve (CFR), which is primarily determined by the coronary microvasculature in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease (CAD). Hence, a reduction in CFR, which is often observed in patients with HCM, is an indicator of microvascular dysfunction.16 However, it is not known whether microvascular dysfunction is a pre-requisite for the development of fibrosis and/or DE in HCM patients.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to investigate the relationship between DE and coronary microvascular function assessed by PET.

Methods

Patients

We enrolled patients from the Johns Hopkins HCM Clinic who fulfilled the standard diagnostic criteria for HCM and underwent cardiac PET and CMR for clinical indications between June of 2009 and May of 2012. The diagnosis of HCM was based on the presence of unexplained LV hypertrophy ≥ 15 mm wall thickness by echocardiography in the absence of other conditions capable of producing a similar degree of hypertrophy (e.g. moderate-to-severe valvular disease).17 We excluded patients with a history of CAD, including surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization and those with prior septal myectomy or alcohol septal ablation. Echocardiography was used to measure LV wall thickness, ejection fraction and outflow tract gradients (resting and provoked).

A total of 62 patients underwent PET and CMR during this interval, however, 8 patients had history of CAD, 5 patients had prior myectomy/alcohol ablation, and 2 patients showed artifacts during DE-CMR phase, and were excluded. The final study population consisted of 47 patients. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Boards approved this study. All participants gave informed consent.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

CMR imaging was performed using a 1.5-T MR imaging unit (Avanto, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Cine and DE sequences were acquired in the short axis (SA) slices and covered the entire LV.

Cardiac Cine Acquisition and Analysis: Retrospective, ECG-gated steady state free precession segmented cine images were acquired in the SA, 2-chamber, 4- chamber and 5-chamber views. Myocardial wall thickness was measured at end-diastole in the SA.

Delayed Enhancement Sequence and Analysis: Delayed enhancement images were acquired at end-diastole during breath-holding using a segmented inversion-recovery gradient-echo turbo fast low angle shot sequence obtained 10-15 min after injection of 0.2 mmol/kilogram of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Bayer) contrast medium. The inversion time was selected to obtain maximal nulling of the signal from the LV. Images were visually scored for the presence or absence of DE. Subsequently, the extent of DE in the LV was quantitatively measured using dedicated software (QMASS version 6.2, Medis, Leiden, The Netherlands). DE was defined by a threshold signal intensity of 6 standard deviations above the mean signal intensity of remote normal myocardium (region without DE on visual assessment).18 This threshold was chosen due to overall good agreement with visual evaluation. The extent of DE was expressed as a % of total LV mass with DE.

Cardiac PET

All patients were imaged using a GE Discovery VCT PET/CT system (GE Healthcare), equipped with an integrated Lutetium Yttrium Orthosilicate scintillator system.

Rest Acquisition: 13N-NH3 (~ 370 MBq [10 mCi]) was injected at baseline and 2-dimensional listmode PET images were acquired for 20 min.

Stress Acquisition: Dipyridamole or Regadenoson was administered for vasodilator stress followed by second injection of 13N-NH3 (20 min 2-dimensional listmode PET stress acquisition). We have previously demonstrated that Dipyridamole- and Regadenoson-induced hyperemia (peak-MBF) is equivalent in patients with HCM.19 In the present study, peak-MBF was highly comparable between Dipyridamole and Regadenoson in HCM patients without DE (2.20 ± 0.41 vs. 2.28 ± 0.52; P = 0.8) and those exhibiting DE (1.79 ± 0.36 vs. 1.77 ± 0.47; P = 0.9).

Quantification of Absolute Flow: Volumetric sampling of the myocardial tracer activity was performed on static images (Munich Heart software). Then, polar map-defined segments were reapplied to the dynamic imaging series to create myocardial time–activity curves. A region of interest was positioned in the LV cavity to obtain the arterial input function. MBF was calculated by fitting the arterial input function and myocardial time–activity curves from the dynamic polar maps to a 2 tissue-compartment tracer kinetic model as previously described.20 MBF of the LV during peak-MBF and rest was measured in mL/min/gm. CFR was determined as the ratio of the peak-MBF to rest MBF. Regions of interest were applied to each flow polar map to obtain regional analysis between the LV septum and lateral wall. Inter-observer agreement for global (R2= 0.88) and regional (R2= 0.85) flow data was very good.

Regional myocardial perfusion (rMP): It was semi-quantitatively assessed by the standard 17-AHA-segmentation, 5-point visual score method based on the level of tracer activity (normal = 0, mildly decreased = 1, moderately decreased = 2, severely abnormal = 3, and absent perfusion = 4) using the CardIQ Physio package (GE Healthcare). The summed stress score (SSS) and summed rest score (SRS) consisted of the summation score of the 17 LV segments during vasodilator-stress and rest perfusion imaging respectively. Summed difference score (SDS) was the difference between SSS and SRS. Abnormal rMP was defined, as an SDS ≥ 2 in this study. 14 Inter-observer (R2 = 0.80) agreement for global SDS was very good.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 19.0). Paired t-test was used to evaluate statistical differences between two continuous measurements or variables of the same individuals. An independent-measures t-test was used to assess continuous variables differences between two groups. One-way analysis of variance combined with Scheffe test for post hoc analysis and correction for multiple comparisons was performed to compare means of more than 2 groups. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to test for statistical differences of continuous variables that had a skewed distribution, and results are given in median in addition to their mean values. Categorical variables were compared between groups using chi-square tests and are presented as percentages. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 47 patients were studied; they were divided into two groups: patients without DE (n=12), and patients with evidence of DE (n=35) on CMR (mean DE 10 ± 10%, range 1-37% of LV mass). DE-positive patients had a higher septal wall thickness, and were more likely to have non-obstructive HCM (Tables 1 and 2). There was no difference in ejection fraction between the DE-negative and DE-positive group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of HCM patients with and without evidence of delayed enhancement on CMR.

| Baseline Characteristics | No DE (n=12) | DE Present (n = 35) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y ± SD | 49 ± 16 | 51 ± 16 | 0.7 |

| Males, % | 6 (50) | 20 (57) | 0.7 |

| Chestpain and/or dyspnea, % | 10 (83) | 28 (80) | 0.8 |

| NYHA Class I, % | 7 (58) | 14 (40) | |

| NYHA Class II, % | 3 (25) | 16 (46) | 0.4 |

| NYHA Class III, % | 2 (17) | 5 (14) | |

| Lightheadedness, % | 5 (42) | 15 (43) | 0.9 |

| Palpitations, % | 1 (8) | 6 (17) | 0.4 |

| Hypertension, % | 5 (42) | 16 (46) | 0.8 |

| Diabetes, % | 1 (8) | 4 (11) | 0.8 |

| Family history of HCM, % | 3 (25) | 6 (17) | 0.5 |

| Beta-blockers, % | 10 (83) | 27 (77) | 0.7 |

| Statin, % | 5 (42) | 13 (37) | 0.8 |

NYHA indicates New York heart association

Table 2.

Echocardiography and CMR characteristics in HCM patients with and without evidence of delayed enhancement

| Charactenstics | No DE (n = 12) | DE Present (n = 35) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | |||

| Interventricular septum thickness, cm | 1.78 ± 0.34 | 2.09 ± 0.44 | 0.03 |

| Left ventricular posterior wall thickness, cm | 0.96 ± 0.12 | 1.17 ± 0.31 | 0.03 |

| Left ventricle septum / posterior wall ratio | 1.94 ± 0.79 | 2.15 ± 2.09 | 0.7 |

| Rest LOVTG, mmHg | 14 ± 12 | 27 ± 27 | 0.1 |

| Peak provoked LVOTG, mmHg | 40 ± 25 | 60 ± 59 | 0.4 |

| Non-obstructive HCM, % | 3 (25) | 17 (49) | |

| Obstructive HCM, % | 1 (8) | 11 (31) | 0.01 |

| Latent HCM, % | 8 (67) | 7 (20) | |

| CMR | |||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 72 ± 9 | 72 ±7 | 0.7 |

| Interventricular septum thickness, cm | 1.66 ± 0.28 | 2.03 ± 0.40 | 0.005 |

Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. LOVTG indicates left ventricular outflow tract gradient

Global and regional absolute flow quantification, CFR, and DE-CMR

Baseline hemodynamics including the rate-pressure-product, and vasodilator-induced hemodynamics were similar in both groups as shown in Table 3. Consequently, MBF and CFR were not corrected by the rate-pressure-product.

Table 3.

Hemodynamics and PET characteristics in HCM patients with and without evidence of delayed enhancement on CMR

| PET Variables | No DE (N=12) | DE Present (N=35) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline heart rate, bpm | 6l ±7 | 6l ± 10 | 0.9 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 135 ± 11 | 133 ± 20 | 0.7 |

| Baseline mean arterial blood pressure, mmHg | 92 ±7 | 89 ± 13 | 0.4 |

| Resting rate-pressure-product, bpm*mmHg | 8314 ± 1370 | 8171 ± 1912 | 0.8 |

| Vasodilator-induced peak heart rate, bpm | 31 ± 15 | 92 ± 17 | 0.9 |

| Heartrate difference, bpm | 30 ± 14 | 31 ± 14 | 0.9 |

| Rest myocardial blood flow, mL/min/gram | 0.82 ± 0.20 | 0.92 ± 0.22 | 0.2 |

| Peak myocardial blood flow, mL/min/gram | 2.25 ± 0.46 | 1.78 ± 0.43 | 0.003 |

| Coronary flow reserve, unitless. | 2.78 ± 0.32 | 2.01 ± 0.52 | <0.0001 |

| Coronary flow reserve < 2.00, % | 0 | 18 (51) | 0.002 |

| Summed difference score, unitless. (median) | 0 | 5 | <0.0001 |

| Abnormal regional myocardial perfusion, % | 3 (25) | 31 (89) | <0.0001 |

Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. Bpm indicates beats per minute

At rest, global MBF showed a trend for higher values in the DE-positive compared to DE-negative group. However during vasodilator stress, both peak-MBF and CFR were significantly lower in the DE-positive group (Table 3). A global CFR < 2.00 was seen in 18 DE-positive patients (51%), but in none of the DE-negative subjects (P <0.0001).

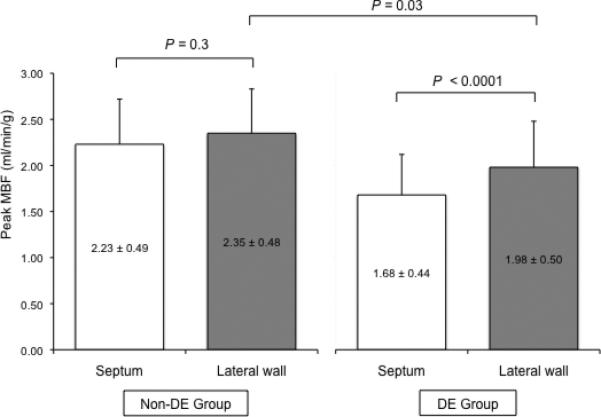

A regional analysis was conducted to investigate MBF differences based on the severity of hypertrophy in patients from both groups (Figure 1): we compared MBF in the septum, the wall that showed the maximum amount of hypertrophy, to the lateral wall that showed a lesser degree of hypertrophy. Within the DE-negative group the septum showed no significant differences in peak-MBF compared to the lateral wall. In contrast, in the DE-positive group the septum exhibited a significantly lower peak-MBF in comparison to the lateral wall. Peak-MBF was significantly lower within the lateral wall of the DE-positive than DE-negative group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Regional analysis that highlights peak-MBF differences between the septum and lateral wall depending on the DE status. Within the group without DE the hypertrophied septum showed no significant differences in peak-MBF compared to the lateral wall. In contrast, in the DE-group the septum exhibited a significantly lower peak-MBF in comparison to the lateral wall. Peak-MBF in the lateral wall was significantly lower in patients with DE compared to those without DE.

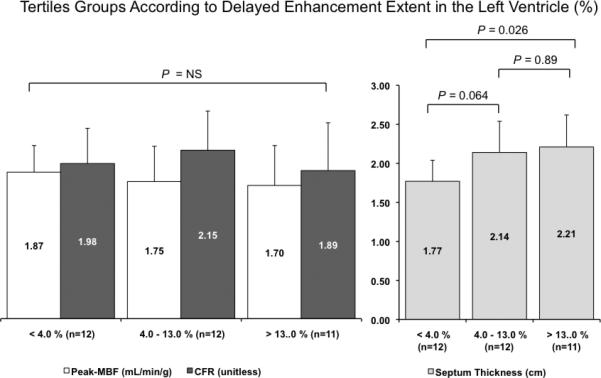

Global peak-MBF (r = -0.44, p = 0.002) and CFR (r = -0.40, p = 0.005) showed a weak correlation with the extent of DE in the LV in the entire cohort (n = 47). However, when DE-positive patients (n = 35) were divided into tertiles based on the extent of DE in the LV, there were no significant differences in peak-MBF (P = 0.6) and CFR (P = 0.5) across the different tertiles, whereas septal wall thickness (P = 0.015) significantly augmented at higher degrees of DE in the LV (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patients with HCM and DE-positive CMR (n = 35) were divided into tertiles based on the extent of DE in the LV. Please note that peak-MBF and CFR are not significantly different across the different tertile groups, whereas septum thickness increases at higher levels of DE in the LV.

Regional Myocardial Perfusion and DE-CMR

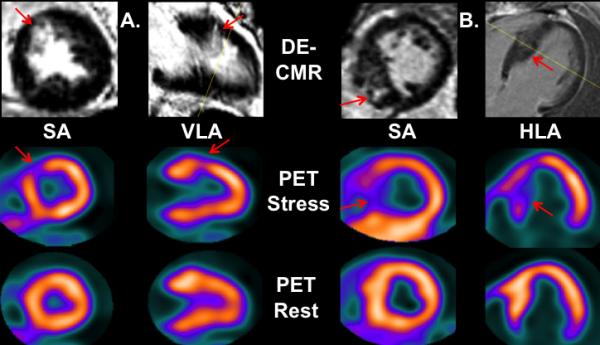

The SDS was undertaken to assess for flow heterogeneity or regional CFR differences, which could be missed by global evaluation of CFR in the LV. The overall SDS was significantly higher in the DE-positive group compared to DE-negative patients. A total of 31 patients had both abnormal rMP (SDS ≥ 2) and evidence of DE on CMR, with majority of the reversible perfusion abnormalities visually matching the myocardial region with DE (Figure 3). On the other hand, 9 patients demonstrated normal rMP and no evidence of DE on CMR, for an overall agreement between rMP by PET and DE by CMR of 85%.

Figure 3.

Matching CMR and PET abnormalities (red arrows) of two patients with HCM that demonstrate concordant DE on CMR and reversible (stress only) regional myocardial perfusion PET abnormalities in the mid anteroseptal wall (patient A) and septum (patient B). Short axis, SA; vertical long axis, VLA; horizontal long axis, HLA.

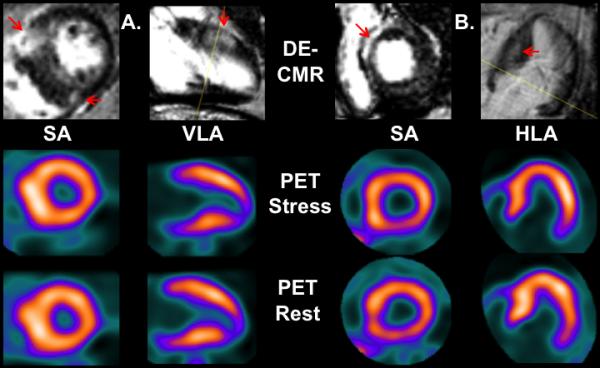

PET and DE-CMR discordance

PET-CMR discordant results occurred in 4 individuals (Figure 4) who were DE-positive but PET-negative. In these patients, the DE extent and wall thickness were similar to DE-positive patients but myocardial ischemia score and CFR were significantly different compared to PET-positive patients (Table 4). The other discordant group, consisted of 3 patients who were DE-negative but PET-positive, albeit the reversible perfusion abnormalities were mild and limited to the apex (SDS range 2 – 4), and global CFR was preserved (CFR range 2.57 – 2.85).

Figure 4.

Discordant CMR and PET images are seen in two different patients with HCM. Please notice the areas of DE on CMR (red arrows) in patients A and B with normal regional myocardial perfusion at these locations on PET. Short axis, SA; vertical long axis, VLA; horizontal long axis, HLA.

Table 4.

Imaging characteristics between patients with concordant and discordant PET-MR scans

| Characteristic | DE-positive PET-positive (n=31) | DE-positive PET-negative (n=4) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range | ||

| DE extent in LV, % | 10.7 ± 10 | 1 – 37 | 8.0 ± 6.4 | 2.5 – 15 | 0.60 |

| Septum thickness, cm | 2.07 ± 0.42 | 1.50 – 2.90 | 2.18 ± 0.59 | 1.7 – 3.0 | 0.67 |

| SDS, unitless (median) | 6.0 | 2–32 | 1.0 | 0– 1 | <0.001 |

| CFR, unitless | 1.90 ± 0.42 | 1.19 – 3.06 | 2.89 ± 0.33 | 2.50 – 3.21 | <0.001 |

SDS indicates summed difference score; CFR, coronary flow reserve

Discussion

Our study demonstrates a close relationship between delayed enhancement on CMR and regional and globally impaired hyperemic myocardial blood flow and coronary flow reserve by PET in a well-characterized HCM cohort. A small proportion of patients (8%) had evidence of DE by CMR but normal regional myocardial perfusion and flow parameters, indicating that DE may exist in the absence of myocardial ischemia in HCM patients.

Microvascular ischemia in HCM

Our results are concordant with the results of a number of studies, employing different imaging modalities, such as PET,21 CMR,11 and echocardiography,22 which have revealed that HCM patients often demonstrate an impaired response to vasodilator stress, translating into abnormal peak-MBF and CFR. In the absence of obstructive CAD, failure to increase MBF during vasodilator stress is considered as evidence for microvascular dysfunction. In HCM, this is believed to be in part secondary to structural alterations in the intramural arterioles (the main source of coronary resistance), characterized by thickening of the small vessel wall and decreased luminal size.10, 23 Ex-vivo studies of hearts from a few HCM patients who died of various causes have found that these microvascular changes are more common in tissue sections demonstrating concomitant significant myocardial fibrosis than in those with mild or absent fibrosis.10, 23 Similarly, the majority of our patients showed evidence of reduced regional perfusion, presumably due to microvascular disease.

Delayed enhancement by CMR and myocardial ischemia in HCM

Our clinical study reveals that patients with evidence of DE had a significantly lower global peak-MBF and CFR in comparison to patients without DE, which implies that microvascular dysfunction and ischemia are more common in this sub-group. Importantly, no patient in the DE-negative group exhibited a global CFR < 2.00, a cut-off value that has consistently being associated with a higher incidence of adverse cardiovascular events including mortality in a number of PET studies. 14, 24-27

On the other hand, 17 patients (49%) who had evidence of DE by CMR had preserved global CFR (≥ 2.00), and despite the obvious significant flow differences of DE-positive compared to DE-negative patients, we observed no definite correlation between the extent of myocardial DE and myocardial flow in HCM (Figure 2). These findings suggest the existence of significant global as well as regional flow heterogeneity in the presence of DE. For example, in the absence of myocardial DE, peak-MBF was similar in the septum and lateral wall, whereas it was significantly lower in the septum of patients with DE. Moreover, myocardial flow in the lateral wall (which showed a lesser degree of hypertrophy) was significantly lower in DE-positive compared to the DE-negative group (Figure 1). These findings indicate that the presence, rather than the extent, of myocardial DE is associated with myocardial flow impairment in HCM.

Some of our regional results are in agreement with Petersen (n=35) 11 and Sotgia (n=34) 28 who observed that peak-MBF (assessed by perfusion-CMR and 13NH3-PET respectively) was significantly lower in myocardial segments with DE and higher in those segments without DE. 11, 28 However, neither of these studies evaluated patients demonstrating preserved myocardial flow in the presence of overt myocardial DE nor the influence of myocardial DE extent on CFR. Moreover, both Sotgia and Peterson seem to support the thesis that DE (fibrosis markers) is the consequence of myocardial ischemia. Our findings demonstrate that DE as marker of fibrosis can exist without evidence of corresponding reductions in perfusion (see below).

Mismatch between DE and regional ischemia in HCM

It is conceivable that in some instances, CMR may detect areas of DE that correspond to perfusions defects that are undetectable by PET given the superior spatial resolution of CMR. This could theoretically result in under-reporting by PET of perfusion defects caused by small patchy areas of replacement fibrosis. In our study, the size of DE as well as wall thickness were similar in DE+ PET+ patients compared to DE+PET- patients as shown in Table 4. Therefore the likelihood of an artifactual underreporting of PET abnormalities due to differences in resolution seems low. All patients in our study had LV wall thicknesses of at least 1.5 cm (range 1.5 – 3.0cm), a cut-off that is at least 2 times the spatial resolution of PET (5 - 7 mm). Consequently, any area of DE occupying 1/3 or more of the LV wall thickness would be, presumptively, within the resolution and detection capabilities of PET and should translate into a myocardial perfusion defect if this area of DE were related to derangement of the coronary microvasculature. This was not the case in a small proportion of the patients (8%), in whom despite significant DE involvement of thickened regions of the heart, myocardial perfusion (as well as quantitative flow) remained unaffected as depicted in Figure 4.

Significance of Delayed enhancement in HCM

Whether or not these regions of DE in patients with HCM represent fibrosis is still unclear. Unlike ischemic heart disease, where DE has been proven to result from replacement fibrosis using animal models,3, 29 no detailed histopathologic correlates of DE in HCM are available. DE is non-specific, resulting from an expansion of extracellular fluid volume in the myocardium, which may be due to fibrosis, myonecrosis/edema or myocyte disarray – all of which frequently occur in HCM patients.

It has been previously postulated that fibrosis may be the result of repetitive episodes of myocardial ischemia due to coronary microvascular disease in HCM.11, 28 Alternatively, fibrosis and disarray may be secondary to specific-genotypes, advanced disease, and/or the expression of a severe phenotype. Furthermore, pre-clinical and clinical data suggest that the stimulus for fibrosis can pre-date hypertrophy,12,30 and in fact, we believe that fibrosis may occur in the absence of coronary microvascular changes in some cases. This is supported by the following data: 1) approximately 8% of DE-positive subjects had normal myocardial perfusion in our cohort, 2) in a necropsy study of 7 HCM individuals with evidence of myocardial replacement fibrosis but no significant atherosclerosis of the epicardial coronaries, abnormal intramural coronary arteries typical of HCM were noted in all but one of these patients. The authors concluded that the causal relation between ischemia and fibrosis cannot be considered definitive,31 and 3) Kwon et al32 observed that histologically-proven small-vessel changes were present in 35 of 38 (92%) post-myectomy specimens of HCM patients who exhibited DE in the basal septum prior to surgery, indicating that a small proportion (8%) of individuals had fibrosis without concomitant small-vessel disease. These findings, support our conclusion that myocardial ischemia is not a pre-requisite for the development of DE in HCM patients.

Clinical Implications

HCM individuals with evidence of DE-CMR have been reported to be at higher risk for adverse events.2, 8 Current ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend the use of DE-CMR in selected patients with known HCM when sudden death risk stratification is inconclusive after documentation of the conventional risk factors (Class: IIb; level of Evidence: C).17 Studies have consistently showed that more than half of HCM patients referred for CMR have DE, but only a fraction of these patients will eventually experience cardiovascular events.2, 6, 8, 33 The apparent inconsistency with which DE predicts clinical events could be partially explained by the presence or absence of concomitant ischemia. Fibrosis markers and perfusion abnormalities can separate the overall HCM population into several subgroups that may better segregate high-risk patients. It remains to be prospectively explored, whether HCM patients with DE on CMR and evidence of concomitant ischemia are at higher risk for adverse events such as sudden cardiac death, since the combination of intermittent ischemia, fibrosis and disarray can be highly proarrhythmic.34,35-37

Limitations

We were unable to obtain histopathologic correlates for DE in our HCM patient cohort since we did not perform myocardial biopsies or use molecular imaging agents that directly bind collagen. Furthermore, our cross-sectional, observational study cannot address whether microvascular dysfunction precedes the development of DE in HCM patients. Availability of genotype and/or histopathology would permit a more detailed analysis of the gene-pathology-ischemia relationship. Others have shown that the prevalence of DE is higher and myocardial flow significantly lower in genotype-positive (for sarcomeric protein mutations) compared to genotype-negative individuals with HCM.38 Lastly, we want to point out that given the relatively small size and potential for variability of regional measurements of our cohort, no definite conclusions can be drawn regarding the relationship between DE and myocardial flow, rather, this is a hypothesis-generating study and larger studies are needed to evaluate the complex implications of DE and microvascular dysfunction/ischemia, including on the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias and heart failure in HCM patients.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a close relationship between DE by CMR and microvascular ischemia by PET in HCM in the majority of patients. However, DE can also occur in the absence of coronary flow impairment, indicating that perfusion abnormalities are important, but not the sole cause of myocardial DE in HCM. Prospective studies are needed to assess the combined use of perfusion and DE imaging for predicting cardiovascular events in HCM.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE SUMMARY.

In the present study we examined the relationship of microvascular ischemia by ammonia PET with markers of fibrosis (DE) by CMR. Our results indicate that presence, not extent, of DE by CMR was closely, but not exclusively, related with impaired microvascular perfusion by ammonia PE suggesting that fibrosis markers are not always associated with ischemia as previously thought. We found HCM patients with DE in the setting of normal PET flow/perfusion indicating that, at least in a sub-group, the process of fibrosis is not related to ischemia. Ischemia-fibrosis profiling of HCM resulted in 3 subgroups: ischemia + fibrosis; ischemia only and fibrosis only. This ischemiafibrosis nexus may better explain the apparent inconsistency with which DE alone predicts clinical events in HCM. For instance, HCM patients with DE on CMR and evidence of microvascular ischemia may be at higher risk for adverse events such as sudden cardiac death, since the combination of intermittent ischemia, fibrosis and disarray can be highly pro-arrhythmic. Larger prospective studies will be needed to clarify if this hypothesis is true and if ischemia-fibrosis profiling offers superior risk prediction information in HCM compared to DE alone.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Nuclear Medicine laboratories, in particular, Jennifer Merrill-Warne and Judy Buchanan; the staff of the Johns Hopkins Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center of Excellence especially the sonographers and nurses of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Echocardiography Laboratories and General Electric Ultrasound, Horten Norway (Glenn Lie and Gunnar Hansen) for providing the software and support for echocardiography analysis. We also thank the staff of the Johns Hopkins Clinical Magnetic Resonance Imaging Laboratories for their assistance.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HL098046).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moon JC, Reed E, Sheppard MN, Elkington AG, Ho SY, Burke M, Petrou M, Pennell DJ. The histologic basis of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2260–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Hanlon R, Grasso A, Roughton M, Moon JC, Clark S, Wage R, Webb J, Kulkarni M, Dawson D, Sulaibeekh L, Chandrasekaran B, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Pasquale F, Cowie MR, McKenna WJ, Sheppard MN, Elliott PM, Pennell DJ, Prasad SK. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ordovas KG, Higgins CB. Delayed contrast enhancement on mr images of myocardium: Past, present, future. Radiology. 2011;261:358–374. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11091882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mewton N, Liu CY, Croisille P, Bluemke D, Lima JA. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moon JC, McKenna WJ, McCrohon JA, Elliott PM, Smith GC, Pennell DJ. Toward clinical risk assessment in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with gadolinium cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1561–1567. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maron MS, Appelbaum E, Harrigan CJ, Buros J, Gibson CM, Hanna C, Lesser JR, Udelson JE, Manning WJ, Maron BJ. Clinical profile and significance of delayed enhancement in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1:184–191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.768119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adabag AS, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, Harrigan CJ, Buros JL, Gibson CM, Lesser JR, Hanna CA, Udelson JE, Manning WJ, Maron MS. Occurrence and frequency of arrhythmias in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in relation to delayed enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1369–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruder O, Wagner A, Jensen CJ, Schneider S, Ong P, Kispert EM, Nassenstein K, Schlosser T, Sabin GV, Sechtem U, Mahrholdt H. Myocardial scar visualized by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predicts major adverse events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:875–887. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maron MS, Olivotto I, Maron BJ, Prasad SK, Cecchi F, Udelson JE, Camici PG. The case for myocardial ischemia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maron BJ, Wolfson JK, Epstein SE, Roberts WC. Intramural (“small vessel”) coronary artery disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:545–557. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen SE, Jerosch-Herold M, Hudsmith LE, Robson MD, Francis JM, Doll HA, Selvanayagam JB, Neubauer S, Watkins H. Evidence for microvascular dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: New insights from multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2007;115:2418–2425. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.657023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JB, Porreca GJ, Song L, Greenway SC, Gorham JM, Church GM, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Polony multiplex analysis of gene expression (pmage) in mouse hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Science. 2007;316:1481–1484. doi: 10.1126/science.1137325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bengel FM, Higuchi T, Javadi MS, Lautamaki R. Cardiac positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Gistri R, Lorenzoni R, Chiriatti G, Camici PG. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349:1027–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Gistri R, Lorenzoni R, Chiriatti G, Girolami F, Torricelli F, Camici PG. Relevance of coronary microvascular flow impairment to long-term remodeling and systolic dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bravo PE, Pinheiro A, Higuchi T, Rischpler C, Merrill J, Santaularia-Tomas M, Abraham MR, Wahl RL, Abraham TP, Bengel FM. Pet/ct assessment of symptomatic individuals with obstructive and nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53:407–414. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.096156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Dearani JA, Fifer MA, Link MS, Naidu SS, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, Rakowski H, Seidman CE, Towbin JA, Udelson JE, Yancy CW. 2011 accf/aha guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Executive summary: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:2761–2796. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318223e230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrigan CJ, Peters DC, Gibson CM, Maron BJ, Manning WJ, Maron MS, Appelbaum E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Quantification of late gadolinium enhancement with contrast-enhanced cardiovascular mr imaging. Radiology. 2011;258:128–133. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bravo PE, Pozios I, Pinheiro A, Merrill J, Tsui BM, Wahl RL, Bengel FM, Abraham MR, Abraham TP. Comparison and effectiveness of regadenoson versus dipyridamole on stress electrocardiographic changes during positron emission tomography evaluation of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchins GD, Schwaiger M, Rosenspire KC, Krivokapich J, Schelbert H, Kuhl DE. Noninvasive quantification of regional blood flow in the human heart using n-13 ammonia and dynamic positron emission tomographic imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90237-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bravo PE, Bengel FM. The role of cardiac pet in translating basic science into the clinical arena. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011;4:425–436. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9285-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soliman OI, Knaapen P, Geleijnse ML, Dijkmans PA, Anwar AM, Nemes A, Michels M, Vletter WB, Lammertsma AA, ten Cate FJ. Assessment of intravascular and extravascular mechanisms of myocardial perfusion abnormalities in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by myocardial contrast echocardiography. Heart. 2007;93:1204–1212. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.110460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka M, Fujiwara H, Onodera T, Wu DJ, Matsuda M, Hamashima Y, Kawai C. Quantitative analysis of narrowings of intramyocardial small arteries in normal hearts, hypertensive hearts, and hearts with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1987;75:1130–1139. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.6.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzog BA, Husmann L, Valenta I, Gaemperli O, Siegrist PT, Tay FM, Burkhard N, Wyss CA, Kaufmann PA. Long-term prognostic value of 13n-ammonia myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography added value of coronary flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziadi MC, Dekemp RA, Williams KA, Guo A, Chow BJ, Renaud JM, Ruddy TD, Sarveswaran N, Tee RE, Beanlands RS. Impaired myocardial flow reserve on rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging predicts adverse outcomes in patients assessed for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, Gaber M, Di Carli G, Blankstein R, Dorbala S, Sitek A, Pencina MJ, Di Carli MF. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2011;124:2215–2224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukushima K, Javadi MS, Higuchi T, Lautamaki R, Merrill J, Nekolla SG, Bengel FM. Prediction of short-term cardiovascular events using quantification of global myocardial flow reserve in patients referred for clinical 82rb pet perfusion imaging. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2011;52:726–732. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.081828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sotgia B, Sciagra R, Olivotto I, Casolo G, Rega L, Betti I, Pupi A, Camici PG, Cecchi F. Spatial relationship between coronary microvascular dysfunction and delayed contrast enhancement in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2008;49:1090–1096. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.050138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arheden H, Saeed M, Higgins CB, Gao DW, Ursell PC, Bremerich J, Wyttenbach R, Dae MW, Wendland MF. Reperfused rat myocardium subjected to various durations of ischemia: Estimation of the distribution volume of contrast material with echo-planar mr imaging. Radiology. 2000;215:520–528. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.2.r00ma38520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho CY, Lopez B, Coelho-Filho OR, Lakdawala NK, Cirino AL, Jarolim P, Kwong R, Gonzalez A, Colan SD, Seidman JG, Diez J, Seidman CE. Myocardial fibrosis as an early manifestation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:552–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maron BJ, Epstein SE, Roberts WC. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and transmural myocardial infarction without significant atherosclerosis of the extramural coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1979;43:1086–1102. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Rodriguez ER, Tan C, Setser R, Thamilarasan M, Lytle BW, Lever HM, Desai MY. Cardiac magnetic resonance detection of myocardial scarring in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Correlation with histopathology and prevalence of ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choudhury L, Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Choi KM, Elliott MD, Klocke FJ, Bonow RO, Judd RM, Kim RJ. Myocardial scarring in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2156–2164. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah M, Akar FG, Tomaselli GF. Molecular basis of arrhythmias. Circulation. 2005;112:2517–2529. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.494476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abraham MR, Selivanov VA, Hodgson DM, Pucar D, Zingman LV, Wieringa B, Dzeja PP, Alekseev AE, Terzic A. Coupling of cell energetics with membrane metabolic sensing. Integrative signaling through creatine kinase phosphotransfer disrupted by m-ck gene knock-out. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24427–24434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farid TA, Nair K, Masse S, Azam MA, Maguy A, Lai PF, Umapathy K, Dorian P, Chauhan V, Varro A, Al-Hesayen A, Waxman M, Nattel S, Nanthakumar K. Role of katp channels in the maintenance of ventricular fibrillation in cardiomyopathic human hearts. Circ Res. 2011;109:1309–1318. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.232918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akar FG, Aon MA, Tomaselli GF, O'Rourke B. The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3527–3535. doi: 10.1172/JCI25371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olivotto I, Girolami F, Sciagra R, Ackerman MJ, Sotgia B, Bos JM, Nistri S, Sgalambro A, Grifoni C, Torricelli F, Camici PG, Cecchi F. Microvascular function is selectively impaired in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sarcomere myofilament gene mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]