Abstract

Parkinson protein 2, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (PARK2) gene mutations are the most frequent causes of autosomal recessive early onset Parkinson's disease and juvenile Parkinson disease. Parkin deficiency has also been linked to other human pathologies, for example, sporadic Parkinson disease, Alzheimer disease, autism, and cancer. PARK2 primary transcript undergoes an extensive alternative splicing, which enhances transcriptomic diversification. To date several PARK2 splice variants have been identified; however, the expression and distribution of parkin isoforms have not been deeply investigated yet. Here, the currently known PARK2 gene transcripts and relative predicted encoded proteins in human, rat, and mouse are reviewed. By analyzing the literature, we highlight the existing data showing the presence of multiple parkin isoforms in the brain. Their expression emerges from conflicting results regarding the electrophoretic mobility of the protein, but it is also assumed from discrepant observations on the cellular and tissue distribution of parkin. Although the characterization of each predicted isoforms is complex, since they often diverge only for few amino acids, analysis of their expression patterns in the brain might account for the different pathogenetic effects linked to PARK2 gene mutations.

1. Introduction

Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations of Parkinson protein 2, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (PARK2) geneare cause (50% of cases) of autosomal recessive forms of PD, usually without atypical clinical features. PARK2 mutations also explain ~15% of the sporadic cases with onset before 45 [1, 2] and act as susceptibility alleles for late-onset forms of Parkinson disease (2% of cases) [3]. Along with Parkinsonism forms, PARK2 gene has been linked to other human pathologies, such as Alzheimer disease [4], autism [5], multiple sclerosis [6], cancer [7, 8], leprosy [9], type 2 diabetes mellitus [10], and myositis [11].

PARK2 gene is located in the long arm of chromosome 6 (6q25.2-q27) and spans more than 1.38 Mb [12, 13]. From the cloning of the first human cDNA [12, 13], PARK2 genomic organization was thought to include only 12 exons encoding one transcript. Many evidences now demonstrate the existence of additional exonic sequences, which can be alternatively included or skipped in mature mRNAs. To date, dozens of PARK2 splice transcripts have been described [14] and have been demonstrated to be differentially expressed in tissue and cells [15–21]. These multiple PARK2 splice variants potentially encode for a wide range of distinct protein isoforms with different structures and molecular architectures. However, the characterization and the distribution of these isoforms have not been deeply detailed yet. While studying PARK2 splice variants mRNAs is relatively simple, differentiating protein isoforms is more complex, since they often diverge only for few amino acids. The complexity of this task could explain the small number of scientific papers on this topic. However, solving this riddle is fundamental to comprehend the precise role of PARK2 in human diseases. The tissue and cell specific expression pattern of PARK2 isoforms, in fact, might account for the different pathogenetic effects linked to this gene.

In this review, we briefly describe the structure of PARK2 gene, its currently known transcript products, and the predicted encoded protein isoforms expressed in human, rat and mouse; the latter are two commonly used animal models for studying human diseases. Then, we illustrate the expression of these isoforms by recapitulating the major literature evidences already available, which have previously unknowingly demonstrated their existence. We focus on the expression and cellular distribution of parkin isoforms in the brain. Finally, we collect in a panel the different parkin antibodies, commercially available, which could be useful for the characterization of the isoforms expression and distribution.

2. PARK2 Alternative Splice Transcripts Produce Isoforms with Different Structures and Functions

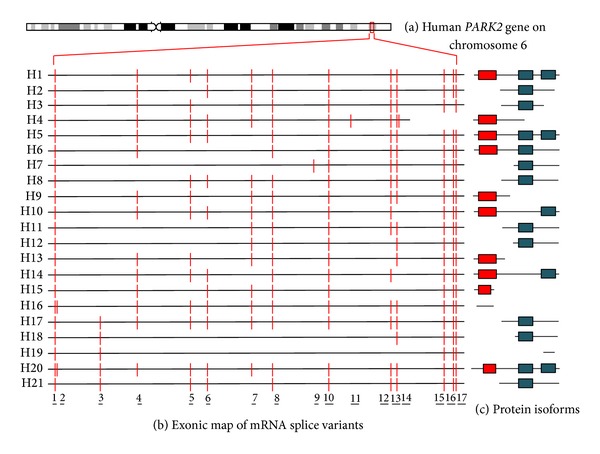

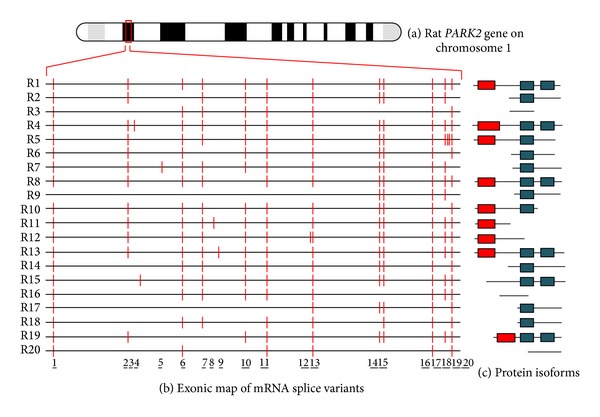

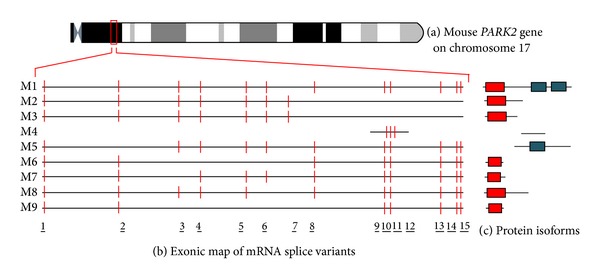

To date, 26 human different cDNAs, corresponding to 21 unique PARK2 alternative splice variants, have been described and are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1. These mature transcripts are derived from the combination of 17 different exonic regions. Similarly, 20 PARK2 transcripts (20 exons) have been characterized in rat (Figure 2 and Table 2) and 9 (15 exons) in mouse (Figure 3 and Table 3). All of them have been carefully described in our previous paper [14]. For each of these variants, the encoded protein isoform, the corresponding molecular weight, and isoelectric point have been predicted and reported in Tables 1, 2, and 3. H8/H17, H9/H13, and H7/H18 isoforms show the same molecular weight and isoelectric point (Table 1), since they have the same amino acid composition; similarly, R2/R7/R14, R17/R18, and R3/R16 show the same primary structure, as shown in Table 2. Although equal, these proteins are encoded by different splice variants which probably produce the same protein with different efficiency.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal localization, exonic structure of alternative splice variants, and corresponding predicted protein isoforms of human PARK2. (a) Cytogenetic location of human PARK2 gene (6q26). (b) Exon organization map of the 21 human PARK2 splice variants currently known. Exons are represented as red bars. The size of introns (black line) is proportional to their length. The codes on left refer to gene identifiers reported in Table 1. (c) Predicted molecular architecture of PARK2 isoforms. Red boxes represent UBQ domain and blue boxes represent IBR domains.

Table 1.

Homo sapiens parkin isoforms.

| New code identifier | GI | Protein accession number | aa sequence | Predicted MW | pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H20 | 469609976 | AGH62057.1 | 530 aa | 58,127 | 6,41 |

| H1 | 3063387 121308969 158258616 169790968 125630744 |

BAA25751.1 BAF43729.1 BAF85279.1 NP_004553.2 ABN46990.1 |

465 aa | 51,65 | 6,71 |

| H5 | 284468410 169790970 |

ADB90270.1 NP_054642.2 |

437 aa | 48,713 | 7,12 |

| H10 | 284468412 | ADB90271.1 | 415 aa | 46,412 | 6,91 |

| H14 | 284516985 | ADB91979.1 | 387 aa | 43,485 | 7,43 |

| H4 | 34191069 | AAH22014.1 | 387 aa | 42,407 | 8,15 |

| H8 | 284468407 | ∗ | 386 aa | 42,52 | 6,65 |

| H17 | 284516991 | ∗ | 386 aa | 42,52 | 6,65 |

| H21 | 520845529 | AGP25366.1 | 358 aa | 39,592 | 7,08 |

| H6 | 169790972 | NP_054643.2 | 316 aa | 35,63 | 6,45 |

| H11 | 284516981 | ∗ | 274 aa | 30,615 | 6,3 |

| H2 | 20385797 | AAM21457.1 | 270 aa | 30,155 | 6,05 |

| H3 | 20385801 | AAM21459.1 | 203 aa | 22,192 | 5,68 |

| H12 | 284516982 | ∗ | 172 aa | 19,201 | 6,09 |

| H9 | 284468408 | ADB90269.1 | 143 aa | 15,521 | 5,54 |

| H13 | 284516983 | ADB91978.1 | 143 aa | 15,521 | 5,54 |

| H7 | 194378189 | BAG57845.1 | 139 aa | 15,407 | 6,41 |

| H18 | 284516993 | ∗ | 139 aa | 15,393 | 6,41 |

| H15 | 284516987 | ADB91980.1 | 95 aa | 10,531 | 8,74 |

| H19 | 469609974 | AGH62056.1 | 61 aa | 6,832 | 10,09 |

| H16 | 284516989 | ADB91981.1 | 51 aa | 5,348 | 7,79 |

H1 represents the canonical sequence cloned by Kitada et al., 1998 [12].

∗ The protein accession number is not present in database.

Figure 2.

Chromosomal localization, exonic structure of alternative splice variants, and corresponding predicted protein isoforms of rat PARK2. (a) Cytogenetic location of rat PARK2 gene (1q11). (b) Exon organization map of the 20 rat PARK2 splice variants currently known. Exons are represented as red bars. The size of introns (black line) is proportional to their length. The codes on left refer to gene identifiers reported in Table 2. (c) Predicted molecular architecture of PARK2 isoforms. Red boxes represent UBQ domain and blue boxes represent IBR domains.

Table 2.

Rattus norvegicus parkin isoforms.

| New code identifier | GI | Protein accession number | aa sequence | Predicted MW | pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R13 | 284810438 | ADB96019.1 | 494 aa | 54,829 | 6,46 |

| R4 | 20385787 | AAM21452.1 | 489 aa | 54,417 | 6,46 |

| R1 | 7229096 7717034 11464986 11527823 7001383 |

BAA92431.1 AAF68666.1 NP_064478.1 AAG37013.1 AAF34874.1 |

465 aa | 51,678 | 6,59 |

| R5 | 20385789 | AAM21453.1 | 446 aa | 49,367 | 6,59 |

| R8 | 20385795 284066979 |

AAM21456.1 ADB77772.1 | 437 aa | 48,734 | 6,74 |

| R15 | 520845531 | AGP25367.1 | 421 aa | 46,854 | 6,59 |

| R10 | 284066981 | ADB77773.1 | 394 aa | 43,297 | 6,06 |

| R19 | 520845539 | AGP25371.1 | 344 aa | 38,558 | 6,13 |

| R2 | 18478865 | AAL73348.1 | 274 aa | 30,641 | 6,2 |

| R7 | 20385793 284810436 |

AAM21455.1 ADB96018.1 | 274 aa | 30,641 | 6,2 |

| R14 | 520845525 520845527 |

AGP25364.1 AGP25365.1 | 274 aa | 30,669 | 6,2 |

| R12 | 284468405 | ADB90268.1 | 256 aa | 28,006 | 6,44 |

| R6 | 20385791 | AAM21454.1 | 203 aa | 22,288 | 5,42 |

| R11 | 284468403 | ADB90267.1 | 193 aa | 21,253 | 8,54 |

| R9 | 20385803 | AAM21460.1 | 177 aa | 19,84 | 5,97 |

| R17 | 520845535 | AGP25369.1 | 139 aa | 15,404 | 6,29 |

| R18 | 520845537 | AGP25370.1 | 139 aa | 15,404 | 6,29 |

| R3 | 18478869 | AAL73349.1 | 111 aa | 12,329 | 6,92 |

| R16 | 520845533 | AGP25368.1 | 111 aa | 12,329 | 6,92 |

| R20 | 520845541 | AGP25372.1 | 86 aa | 9,929 | 7,5 |

Figure 3.

Chromosomal localization, exonic structure of alternative splice variants, and corresponding predicted protein isoforms of mouse PARK2. (a) Cytogenetic location of mouse PARK2 gene (A3.2-A3.3). (b) Exon organization map of the 9 mouse PARK2 splice variants currently known. Exons are represented as red bars. The size of introns (black line) is proportional to their length. The codes on left refer to gene identifiers reported in Table 3. (c) Predicted molecular architecture of PARK2 isoforms. Red boxes represent UBQ domain and blue boxes represent IBR domains.

Table 3.

Mus musculus parkin isoforms.

| New code identifier | GI | Protein accession number | aa sequence | Predicted MW | pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 10179808 118131140 5456929 86577675 |

AAG13890.1 NP_057903.1 BAA82404.1 AAI13205.1 |

464 aa | 51,617 | 6,9 |

| M5 | 220961631 | ∗ | 274 aa | 30,631 | 6,54 |

| M2 | 10179810 | AAG13891.1 | 262 aa | 28,7 | 7,57 |

| M3 | 10179812 | AAG13892.1 | 255 aa | 28,154 | 8,49 |

| M8 | 220961637 | ACL93283.1 | 214 aa | 23,388 | 6,51 |

| M7 | 220961635 | ACL93282.1 | 106 aa | 11,482 | 9,3 |

| M4 | 74227131 | ∗ | 75 aa | 8,053 | 8,85 |

| M6 | 220961633 | ACL93281.1 | 65 aa | 7,181 | 5,62 |

| M9 | 284829878 | ADB99567.1 | 63 aa | 6,967 | 6,53 |

*The protein accession number is not present in database.

In addition to primary structures, molecular architectures and domains composition have also been evaluated (Figures 1, 2, and 3 panels (b) and (c)). As previously described, the original (canonical) PARK2 protein (Accession number BAA25751.1) [12] comprises an N-terminal ubiquitin-like (UBQ) domain and two C-terminal in-between ring fingers (IBR) domains. The UBQ domain targets specific protein substrates for proteasome degradation, whereas IBR domains occur between pairs of ring fingers and play a role in protein quality control. PARK2 encoded isoforms structurally diverge from the canonic one for the presence or absence of the UBQ domain and for one of or both IBR domains. Moreover, when the UBQ domain is present, it often differs in length from that of the canonical sequence. Interestingly, some isoforms miss all of these domains.

The different molecular architectures and domain composition of isoforms might roughly alter also their functions. Parkin protein acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and is responsible of substrates recognition for proteasome-mediated degradation. PARK2 tags various types of proteins, including cytosolic (Synphilin-1, Pael-R, CDCrel-1 and 2a, α-synuclein, p22, and Synaptotagmin XI) [25–29], nuclear (Cyclin E) [15], and mitochondrial ones (MFN1 and MFN2, VDAC, TOM70, TOM40 and TOM20, BAK, MIRO1 and MIRO2, and FIS1) [30–34]. The number of targets is so high that parkin protein results involved in numerous molecular pathways (proteasome-degradation, mitochondrial homeostasis, mitophagy, mitochondrial DNA stability, and regulation of cellular cycle). To date it is unknown if all these functions are mediated by a single protein or by different isoforms. However, considering that parkin mRNAs have a different expression and distribution in tissues and cells [14], which should be also mirrored at the protein level, it is reasonable to hypotisize that these distinct isoforms might perfom specific functions and could be differentially expressed in each cellular phenotype. Each PARK2 splice variants may acts in different manner to suit cell specific needs. This hypothesis is supported by previous evidences showing different and even opposite functions of other splice variants, such as BCl2L12 pattern expression related to cellular phenotype [35]. Finally, based on the extensive alternative splicing process of PARK2 gene, we cannot rule out that additional splice variants with different functions (beyond those listed) may exist.

3. Evidences of Multiple Parkin Isoforms in Brain

A remarkable number of papers have demonstrated the existence, in human and other species, of different mRNA parkin variants [15–21]. However, few of them have investigated parkin isoforms existence, and some have done it without the awareness of PARK2 complex splicing [23, 36, 37]. In fact, although many mRNA parkin splice variants have been cloned, the corresponding proteins have been only deduced through the analysis of the longest open reading frame and uploaded on protein databases as predicted sequences. To date many questions are still unanswered: Are all mRNA parkin splice variants translated? Does a different expression pattern of parkin proteins, in tissue and cells, exist? Does each protein isoform have a specific function? In the following paragraphs we try to answer these questions by summarizing the knowledge accumulated over the last three decades on parkin expression and distribution in human, rat, and mouse brain. Existing data are reinterpreted by considering the complexity level of PARK2 gene splicing described above.

Many conflicting data emerges in the literature regarding the number and relative electrophoretic mobility of parkin proteins. While the majority of papers reported only a band of ~52 kDa corresponding to the canonical parkin isoform, also known as full length parkin, additional bands (from ~22 kDa to ~100 kDa) both in rodent [23, 28, 36–41] and human brain regions were also detected [22–25, 39, 42–45].

Parkin was observed both in rat central and peripheral nervous system. Two major bands of ~50 and ~44 kDa were recognized in cell extracts from rat Substantia Nigra (SN) and cerebellum by western blot analysis. In adrenal glands there were visualized several immunoreactive bands of 50, 69–66, and 89 kDa [36]. Additional bands were also observed in primary cultures of cortical type I astrocytes [37].

Similar result was observed in mouse brain homogenate: a major band of 50 kDa and fainter bands of ~40 and 85/118 kDa were identified on immunoblot. In all these papers, lower and higher molecular weight bands were described as posttranslational modification or proteolytic cleavage of 52 kDa canonical protein or heterodimers resulting from the interaction of parkin with other proteins [42]. However, we speculate that they might correspond to multiple parkin isoforms with different molecular weight.

In knocked-out mice for parkin exon 2, several unexpected bands were also observed on immunoblot. This was interpreted as antibody cross-reactivity with nonauthentic parkin protein [46]. However, as shown in Figure 3, these bands might represent isoforms encoded by splice variants not containing the deleted exon (i.e., M5 and M4).

Parkin expression was also demonstrated in human brains of normal and sporadic Parkinson disease (PD) subjects, but it was absent in any regions of AR-JP brain [22, 23]. A major band of 52 kDa and a second fainter band of ~41 kDa were observed on immunoblot from human frontal cortex of PD patients and control subjects [22]. Parkin expression was also observed in Lewy bodies (LBs), characteristic neuronal inclusions in PD brain. However, in this regard we highlight widely varying results. Initially, the parkin protein expression was reported in neurons of the SN, locus coeruleus, putamen, and frontal lobe cortex of sporadic PD and control individuals but no parkin-immunoreactivity (IR) was found in SN LBs of PD patients [22, 23]. Later on, parkin-IR was described in nigral LBs of four related human disorders, sporadic PD, α-synuclein-linked PD, LB positive parkin-linked PD, and dementia with LBs (DBL) [24]. These discrepant results might be due to the antibodies used. In fact, as shown in Table 4, aligning the epitope sequence recognized by the antibody to each isoform sequence, we discovered that every antibody identifies a pool of different isoforms.

Table 4.

Parkin isoforms recognized by antibodies used in some studies.

| Name | Target | Recognized Parkin isoforms |

|---|---|---|

| M73 (Shimura et al., 1999) [22] | 124–137 | H1, H4, H5, H8, H9, H10, H13, H14, H17, H20, H21 |

| M74 (Shimura et al., 1999) [22] | 293–306 | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H8, H10, H11, H14, H17, H20, H21 |

| ParkA (Huynh et al., 2000) [23] | 96–109 | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H8, H9, H10, H11, H13, H14, H17, H20, H21 |

| ParkB (Huynh et al., 2000) [23] | 440–415 | H1, H2, H5, H6, H7, H8, H10, H11, H12, H14, H17, H18, H20, H21 |

| HP6A (Schlossmacher et al., 2002) [24] | 6–15 | H1, H4, H5, H6, H9, H10, H13, H14, H16, H20 |

| HP7A (Schlossmacher et al., 2002) [24] | 51–62 | H1, H4, H5, H6, H9, H10, H13, H14, H15, H20 |

| HP1A (Schlossmacher et al., 2002) [24] | 84–98 | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H8, H9, H10, H11, H13, H14, H17, H20, H21 |

| HP2A (Schlossmacher et al., 2002) [24] | 342–353 | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, H8, H11, H12, H17, H18, H20, H21 |

| HP5A (Schlossmacher et al., 2002) [24] | 453–465 | H1, H2, H5, H6, H7, H8, H10, H11, H12, H14, H17, H18, H20, H21 |

In accord with this hypothesis, we also explain discordant results observed by Schlossmacher et al. (2002) regarding the cellular distribution of the protein. In fact, they described strongly labeled cores of classical intracellular LBs in pigmented neurons of the SN in PD and DLB patients by using HP2A antibody, whereas HP1A and HP7A antibodies intensively labeled cytoplasmic parkin, in a granular pattern, of cell bodies and proximal neurites of dopaminergic neurons in both diseased and normal brains [24]. These results might represent a different cellular expression profile of parkin isoforms in healthy and diseased human brains.

This hypothesis is supported by another study demonstrating a different expression profile of parkin mRNA splice variants in frontal cortex of patients with common dementia with LB, pure form of dementia with LB, and Alzheimer disease suggesting the direct involvement of isoform-expression deregulation in the development of such neurodegenerative disorders [17]. To date there exists only one paper that has dealt with parkin amino acid sequencing [47]. Trying to ensure that the signal observed on human serum by western blot analysis belongs to parkin protein, they cut off the area on the blot between 50 and 55 kDa in two separate pieces and performed a MALDI-TOF analysis on each. Peptides peaks analysis revealed the presence of six other proteins with similar sequence to canonical one. However, authors did not even speculate that they could represent additional parkin isoforms.

Further evidences on the existence of multiple isoforms come from the conflicting data on their tissue and cellular distribution. Parkin protein is particularly abundant in the mammalian brain and retina [22, 23, 36, 48, 49]. In human, parkin immunoreactivity (IR) has been observed in SN, locus coeruleus, putamen, and frontal lobe cortex [22, 23]. Similarly, it has been strongly measured in rat hippocampus, amygdaloid nucleus, endopiriform nucleus, cerebral cortex, colliculus, and SN (pars compacta and pars reticulata) [37, 50].

Analog parkin distribution was reported in mouse. Most immunoreactive cells were found in the hindbrain. In the cerebellum only the cells within the cerebellar nuclei were positive, while the structures located in the mesencephalon presented moderate to strong immunopositivity. In the ventral part of the mesencephalon the red nucleus showed large strongly stained cells. In the SN moderate parkin immunoreactivity was confined to the pars reticulate. In the dorsal mesencephalon, immunopositive cells were found in the intermediate and deep gray layer of the superior colliculus and in all parts of the inferior colliculus [12, 36, 41, 51].

Although in most brain regions good correlations between parkin-IR and mRNA were observed, incongruent data emerged from some paper in rat SNc (substantia nigra pars compacta), hippocampus, and cerebellar Purkinje cells distribution, where mRNA was detected but no parkin-IR was revealed [23, 36].

Furthermore, in an early study, parkin was described in cytoplasm, in granular structure, and in neuronal processes but was absent in the nucleus [22]. Subsequently other studies reported also its nuclear localization [23, 37, 48, 52–54]. Finally, some papers have also observed a small mitochondrial pool of the protein [55, 56]. All these evidences have suggested that protein could localize to specific subcellular structure under some circumstances. However, it is also reasonably hypothesized that a specific pattern of subcellular distribution of parkin isoforms is related to each cellular phenotype, since in all these papers, protein immunolocalization was performed by using antibodies recognizing different epitopes. Some discrepancies are also observed in the expression of parkin in the SNc of patients affected by other forms of parkinsonism [23].

Brain isoforms might have different species-specific biochemical characteristics, when comparing murine versus human parkin. In fact, it has been shown that mouse protein is easily extracted from brain by high salt buffer, instead human parkin is only extracted with harsher buffers, especially in elderly. This suggested that human parkin becomes modified or interacts with other molecules with age, and this alters its biochemical properties [42]. However, we cannot rule out that this may correlate to a specific expression pattern of isoforms with different biochemical properties in the brains of rodents and humans relative to age.

All of these observations were also supported by contradictory results emerging from clinical studies. Initially, recessive mutations in the parkin gene were related to sporadic early onset parkinsonism [2]; however, the mode of transmission was subsequently rejected by other genetic studies with not only homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations, but also single heterozygous mutations, affecting only one allele of the gene [2, 57–61]. It has been suggested that haploinsufficiency is a risk factor for disease, but certain mutations are dominant, conferring dominant-negative or toxic gain of functions of parkin protein [61]. However, in light of the evidence outlined above, it is possible that some single heterozygous mutation might affect gene expression by inducing loss of function of some isoforms and gain of function of other.

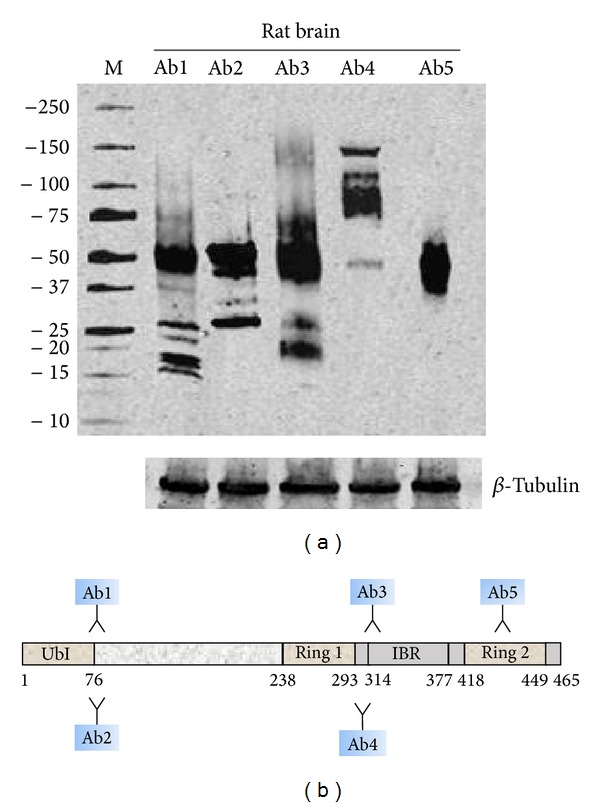

4. The Diversified Panel of Antibodies Commercially Available against PARK2

To date more than 160 PARK2 antibodies are commercially available. They are obtained from different species (generally rabbit or mouse) and commercialized by various companies. Table 5 lists 32 commercially available PARK2 antibodies whose immunogens used are specified by providers in datasheet. Some of them recognize a common epitope, therefore, have been included in the same group. Tables 6, 7, and 8 report, respectively, human, rat, and mouse parkin isoforms recognized by these antibodies. When the amino acid sequence recognized by the antibody perfectly match with the sequence of the protein, it is very likely to get a signal by western blot or immunohistochemistry analysis (this is indicated in the table by “Yes”). Instead, if the antibody recognizes at least 8 consecutive amino acids on the protein, it is likely to visualize a signal both by western blot or immunohistochemistry analysis (this is indicated in the table by “May be”). Finally, if the antibody recognizes less than 8 consecutive amino acids, it could rule out the possibility to visualize a signal on immunoblot or immunohistochemistry analysis (this is indicated in the table by “No”). The use of these 32 antibodies may allow the identification of at least 15 different PARK2 epitopes (Table 5). Although no epitope is isoform specific, the combinatorial use of antibodies targeting different protein regions may provide a precious aid to decode the exact spectrum of PARK2 isoforms expressed in tissues and cells. An example of combinatorial use of antibodies has been reported in Figure 4. On rat brain homogenate, these five antibodies raised against different parkin epitopes, revealed the canonical ~50 kDa band, but additional putative bands of higher and lower molecular weight were visualized. This experimental data reinforce the existence of more than one parkin isoform and confirm that the investigation of parkin expression profile should not be restricted to the use of a single antibody. The latter approach, in fact, could not reveal the entire spectrum of parkin variants.

Table 5.

List of antibodies targeting PARK2 isoforms.

| Antibody group # | Generic name | Target domain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trade name | Companies | ||

| #1 | H00005071-B01P | Abnova | 1 aa–387 aa |

| H00005071-D01P | Abnova | ||

| H00005071-D01 | Abnova | ||

|

| |||

| #2 | OASA06385 | Aviva System biology | 83 aa–97 aa |

| AHP495 | AbD Serotec | ||

| MD-19-0144 | Raybiotech, Inc. | ||

| DS-PB-01562 | Raybiotech, Inc. | ||

| PAB14022 | Abnova | ||

|

| |||

| #3 | MCA3315Z | AbD Serotec | 288 aa–388 aa |

| H00005071-M01 | Abnova | ||

|

| |||

| #4 | PAB1105 | Abnova | 62 aa–80 aa |

| 70R-PR059 | Fitzgerald | ||

|

| |||

| #5 | PAB0714 | Abnova | 305 aa–323 aa |

| AB5112 | Millipore Chemicon | ||

| R-113-100 | Novus biologicals | ||

|

| |||

| #6 | P5748 | Sigma | 298 aa–313 aa |

| GTX25667 Parkin antibody CR20121213_GTX25667 |

GeneTex International Corporation |

||

| ABIN122870 | Antibodies on-line | ||

| PA1-751 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. |

||

|

| |||

| #7 | R-114-100 | Novus biologicals | 295 aa–311 aa |

| Anti-Parkin, aa295-311 h Parkin; C-terminal |

Millipore Chemicon | ||

|

| |||

| #8 | MAB5512 | Millipore Chemicon | 399 aa–465 aa |

| Anti-Parkin antibody, clone PRK8/05882 |

Millipore Upstate | ||

| Parkin (PRK8): sc-32282 | Santa Cruz | ||

|

| |||

| #9 | Parkin (H-300): sc-30130 | Santa Cruz | 61 aa–360 aa |

| Parkin (D-1): sc-133167 | Santa Cruz | ||

| Parkin (H-8): sc-136989 | Santa Cruz | ||

|

| |||

| #10 | EB07439 | Everest Biotech | 394 aa–409 aa |

| GTX89242 PARK2

antibody, internal CR20121213_GTX89242 |

GeneTex International Corporation |

||

| NB100-53798 | Novus biologicals | ||

|

| |||

| #11 | GTX113239 Parkin antibody [N1C1] CR20121213_GTX113239 |

GeneTex International Corporation | 28 aa–258 aa |

|

| |||

| #12 | 10R-3061 | Fitzgerald | 390 aa–406 aa |

|

| |||

| #13 | A01250-40 | GenScript | 300 aa–350 aa |

|

| |||

| #14 | NB600-1540 | Novus biologicals | 399 aa–412 aa |

|

| |||

| #15 | ARP43038_P050 | Aviva System biology | 311 aa–360 aa |

|

| |||

Antibodies against canonical PARK2 isoform (NP_004553.2) were grouped if they recognize the same epitope. To each group was assigned a new identification code (#).

Table 6.

Homo sapiens.

| New code identifier | Ab #1 | Ab #2 | Ab #3 | Ab #4 | Ab #5 | Ab #6 | Ab #7 | Ab #8 | Ab #9 | Ab #10 | Ab #11 | Ab #12 | Ab #13 | Ab #14 | Ab #15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H20 | May be (360 aa) | Yes | May be (64 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (299 aa) | May be (17 aa) | May be (230 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (47 aa) |

| H1 | May be (360 aa) | Yes | May be (64 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (17 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (47 aa) |

| H5 | May be (333 aa) | Yes | May be (64 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (271 aa) | May be (17 aa) | May be (202 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (47 aa) |

| H10 | May be (311 aa) | Yes | May be (22 aa) | Yes | No | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | May be (250 aa) | May be (17 aa) | May be (230 aa) | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| H14 | May be (283 aa) | Yes | May be (22 aa) | Yes | No | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | May be (222 aa) | May be (17 aa) | yes (partial match 202 aa/231 aa) | Yes | May be (12 aa) | May be (15 aa) | No |

| H4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | May be (299 aa) | No | May be (230 aa) | No | Yes | No | May be (47 aa) |

| H8 | May be (274 aa) | Yes | May be (64 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (281 aa) | May be (17 aa) | May be (178 aa) | Yes | Yes | May be (15 aa) | May be (47 aa) |

| H17 | May be (274 aa) | Yes | May be (64 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (280 aa) | May be (17 aa) | May be (178 aa) | Yes | Yes | May be (15 aa) | May be (47 aa) |

| H21 | May be (254 aa) | Yes | May be (64 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (252 aa) | May be (17 aa) | May be (150 aa) | Yes | Yes | May be (15 aa) | May be (47 aa) |

| H6 | May be (148 aa) | No | May be (64 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (52 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| H11 | May be (162 aa) | No | May be (64 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (66 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| H2 | May be (161 aa) | No | May be (64 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (67 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| H3 | May be (161 aa) | No | May be (64 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | May be (67 aa) | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| H12 | May be (42 aa) | No | May be (42 aa) | No | May be (12 aa) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | May be (39 aa) | Yes | Yes |

| H9 | May be (137 aa) | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | May be (110 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| H13 | May be (137 aa) | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | May be (110 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| H7 | May be (27 aa) | No | May be (27 aa) | No | No | No | No | Yes | May be (30 aa) | Yes | No | Yes | May be (24 aa) | Yes | Yes |

| H18 | May be (27 aa) | No | May be (27 aa) | No | No | No | No | Yes | May be (30 aa) | Yes | No | Yes | May be (24 aa) | Yes | Yes |

| H15 | May be (65 aa) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | May be (38 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| H19 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| H16 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Yes = perfect match between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope.

May be = partial match between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope; in parenthesis number of amino acid matching/total number of amino acid recognized by antibody epitope.

No = matching between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope is less than 8 consecutive amino acids.

Table 7.

Rattus norvegicus.

| New code identifier | Ab #1 | Ab #2 | Ab #3 | Ab #4 | Ab #5 | Ab #6 | Ab #7 | Ab #8 | Ab #9 | Ab #10 | Ab #11 | Ab #12 | Ab #13 | Ab #14 | Ab #15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R13 | May be (306 aa) | May be (5 aa) | May be (69 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (66 aa) | May be (248 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (180 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (48 aa) |

| R4 | May be (307 aa) | May be (5 aa) | May be (69 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (66 aa) | May be (247 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (179 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (49 aa) |

| R1 | May be (307 aa) | May be (5 aa) | May be (70 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (66 aa) | May be (249 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (180 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (49 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (49 aa) |

| R5 | May be (305 aa) | May be (5 aa) | May be (69 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (31 aa) | May be (247 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (179 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (48 aa) |

| R8 | May be (279 aa) | May be (5 aa) | May be (69 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (66 aa) | May be (221 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (153 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (48 aa) |

| R15 | May be (254 aa) | May be (5 aa) | May be (73 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (66 aa) | May be (248 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (153 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (49 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (49 aa) |

| R10 | May be (173 aa) | May be (5 aa) | May be (69 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (9 aa) | May be (248 aa) | No | May be (180 aa) | No | May be (48 aa) | No | May be (48 aa) |

| R19 | May be (162 aa) | No | May be (70 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (68 aa) | May be (173 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (74 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (49 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (49 aa) |

| R2 | May be (147 aa) | No | May be (72 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (68 aa) | May be (156 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (55 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (48 aa) |

| R7 | May be (147 aa) | No | May be (72 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (68 aa) | May be (153 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (55 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (49 aa) |

| R14 | May be (149 aa) | No | May be (73 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (68 aa) | May be (155 aa) | May be (14 aa) | May be (56 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (49 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (49 aa) |

| R12 | May be (196 aa) | May be (5 aa) | No | May be (14 aa) | No | No | No | May be (9 aa) | May be (138 aa) | No | May be (168 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| R6 | May be (147 aa) | No | May be (69 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | May be (153 aa) | No | May be (55 aa) | No | May be (48 aa) | No | May be (48 aa) |

| R11 | May be (139 aa) | May be (5 aa) | No | May be (14 aa) | No | No | No | No | May be (82 aa) | No | May be (112 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| R9 | May be (60 aa) | No | May be (68 aa) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | May be (68 aa) | May be (67 aa) | May be (14 aa) | No | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (48 aa) |

| R17 | May be (25 aa) | No | May be (33 aa) | No | No | No | No | May be (68 aa) | May be (32 aa) | May be (14 aa) | No | May be (15 aa) | May be (22 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (35 aa) |

| R18 | May be (25 aa) | No | May be (33 aa) | No | No | No | No | May be (68 aa) | May be (32 aa) | May be (14 aa) | No | May be (15 aa) | May be (22 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (35 aa) |

| R3 | May be (87 aa) | No | No | No | No | No | No | May be (8 aa) | May be (86 aa) | No | May be (55 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| R16 | May be (87 aa) | No | No | No | No | No | No | May be (8 aa) | May be (86 aa) | No | May be (55 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| R20 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | May be (66 aa) | No | May be (14 aa) | No | May be (15 aa) | No | May be (13 aa) | No |

Yes = perfect match between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope.

May be = partial match between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope; in parenthesis number of amino acid matching/total number of amino acid recognized by antibody epitope.

No = matching between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope is less than 8 consecutive amino acids.

Table 8.

Mus musculus.

| New code identifier | Ab #1 | Ab #2 | Ab #3 | Ab #4 | Ab #5 | Ab #6 | Ab #7 | Ab #8 | Ab #9 | Ab #10 | Ab #11 | Ab #12 | Ab #13 | Ab #14 | Ab #15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | May be (294 aa) | No | May be (61 aa) | May be (13 aa) | May be (18 aa) | Yes | Yes | May be (70 aa) | May be (244 aa) | No | May be (176 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes |

| M5 | May be (147 aa) | No | May be (62 aa) | No | May be (18 aa) | Yes | Yes | May be (70 aa) | May be (153 aa) | No | May be (55 aa) | May be (15 aa) | May be (48 aa) | May be (14 aa) | Yes |

| M2 | May be (191 aa) | No | No | May be (13 aa) | No | No | No | No | May be (134 aa) | No | May be (164 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| M3 | May be (192 aa) | No | No | May be (13 aa) | No | No | No | No | May be (135 aa) | No | May be (165 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| M8 | May be (161 aa) | No | No | May be (13 aa) | No | No | No | No | May be (106 aa) | No | May be (136 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| M7 | May be (53 aa) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | May be (27 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| M4 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| M6 | May be (53 aa) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | May be (27 aa) | No | No | No | No |

| M9 | May be (53 aa) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | May be (27 aa) | No | No | No | No |

Yes = perfect match between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope.

May be = partial match between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope; in parenthesis number of amino acid matching/total number of amino acid recognized by antibody epitope.

No = matching between predicted protein sequence and antibody epitope is less than 8 consecutive amino acids.

Figure 4.

Differential detection of parkin isoforms in rat brain using five anti-parkin antibodies. (a) Representative immunoblot of parkin isoforms in rat brain visualized by using five different antibodies. Ab1, Ab2, Ab3, Ab4, and Ab5 correspond to groups #3, #4, #5, #8, and #9 of Table 5. Immunoblot for β-tubulin was used as loading control. (b) Canonical parkin sequence domains recognized by the five antibodies.

5. Conclusion

Alternative splicing is a complex molecular mechanism that increases the functional diversity without the need for gene duplication. Alternative splicing performs a crucial regulatory role by altering the localization, function, and expression level of gene products, often in response to the activities of key signaling pathways [62]. PARK2 gene, as the vast majority of multiexon genes in humans, undergoes alternative splicing [14, 63, 64]. The importance of alternative splicing in the regulation of diverse biological processes is highlighted by the growing list of human diseases associated with known or suspected splicing defects, including PD [65].

Mutations that affect PARK2 splicing could modify the levels of correctly spliced transcripts, alter their localization, and lead to a loss of function of some of them and/or gain of function of others in time- and cell-specific manner. Even if few, some evidences supporting this hypothesis have been already described. Preliminary studies reported PARK2 isoforms with defective degradation activity of cyclin E and control of cellular cycle [15] or characterized by altered solubility and intracellular localization [66]. No evidence of gain of function has been reported, but it is plausible, because a functional screen of the PARK2 splice variants has not been done yet. The huge number of molecular targets attributed to full-size parkin protein could be shared by the others parkin isoforms which could have additional biological activities that until now are uncosidered. In light of this consideration, alteration of the natural splicing of PARK2 and deregulation in the expression of parkin isoforms might lead to the selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in SN of ARJP. However this is a hypothesis, since the functional screen of the PARK2 splice variants is not available and this field is still unexplored.

All these could, at least in part, justifying the conflicting and heterogeneous data of studies revised in this work, which preceded the knowledge of PARK2 alternative splicing and expression of multiple isoforms for this gene. Understanding PARK2 alternative splicing could open up new scenarios for the resolution of some Parkinsonian syndrome.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Bonifati V. Autosomal recessive parkinsonism. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2012;18(supplement 1):S4–S6. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lücking CB, Dürr A, Bonifati V, et al. Association between early-onset Parkinson's disease and mutations in the parkin gene. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(21):1560–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveira SA, Scott WK, Martin ER, et al. Parkin mutations and susceptibility alleles in late-onset Parkinson's disease. Annals of Neurology. 2003;53(5):624–629. doi: 10.1002/ana.10524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns MP, Zhang L, Rebeck GW, Querfurth HW, Moussa CE- Parkin promotes intracellular Aβ1-42 clearance. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18(17):3206–3216. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glessner JT, Wang K, Cai G, et al. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459(7246):569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witte ME, Bol JGJM, Gerritsen WH, et al. Parkinson's disease-associated parkin colocalizes with Alzheimer's disease and multiple sclerosis brain lesions. Neurobiology of Disease. 2009;36(3):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cesari R, Martin ES, Calin GA, et al. Parkin, a gene implicated in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism, is a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 6q25-q27. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(10):5956–5961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931262100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veeriah S, Taylor BS, Meng S, et al. Somatic mutations of the Parkinson's disease-associated gene PARK2 in glioblastoma and other human malignancies. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(1):77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mira MT, Alcaïs A, van Thuc H, et al. Susceptibility to leprosy is associated with PARK2 and PACRG . Nature. 2004;427(6975):636–640. doi: 10.1038/nature02326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wongseree W, Assawamakin A, Piroonratana T, Sinsomros S, Limwongse C, Chaiyaratana N. Detecting purely epistatic multi-locus interactions by an omnibus permutation test on ensembles of two-locus analyses. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10, article 294 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen KM, Veereshwarayya V, Moussa CE, et al. Parkin protects against mitochondrial toxins and β-amyloid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(18):12809–12816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392(6676):605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumine H, Saito M, Shimoda-Matsubayashi S, et al. Localization of a gene for an autosomal recessive form of juvenile parkinsonism to chromosome 6q25.2-27. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1997;60(3):588–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.la Cognata V, Iemmolo R, D’Agata V, et al. Increasing the coding potential of genomes through alternative splicing: the case of PARK2 gene. Current Genomics: Bentham Science. 2014;15(3):203–216. doi: 10.2174/1389202915666140426003342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeuchi K, Marusawa H, Fujiwara M, et al. Attenuation of proteolysis-mediated cyclin E regulation by alternatively spliced Parkin in human colorectal cancers. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;125(9):2029–2035. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Shimizu N. Molecular cloning, gene expression, and identification of a splicing variant of the mouse parkin gene. Mammalian Genome. 2000;11(6):417–421. doi: 10.1007/s003350010080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beyer K, Domingo-Sàbat M, Humbert J, Carrato C, Ferrer I, Ariza A. Differential expression of alpha-synuclein, parkin, and synphilin-1 isoforms in Lewy body disease. Neurogenetics. 2008;9(3):163–172. doi: 10.1007/s10048-008-0124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humbert J, Beyer K, Carrato C, Mate JL, Ferrer I, Ariza A. Parkin and synphilin-1 isoform expression changes in Lewy body diseases. Neurobiology of Disease. 2007;26(3):681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan EK, Shen H, Tan JMM, et al. Differential expression of splice variant and wild-type parkin in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurogenetics. 2005;6(4):179–184. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'agata V, Cavallaro S. Parkin transcript variants in rat and human brain. Neurochemical Research. 2004;29(9):1715–1724. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000035807.25370.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunada Y, Saito F, Matsumura K, Shimizu T. Differential expression of the parkin gene in the human brain and peripheral leukocytes. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;254(3):180–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00697-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S, et al. Immunohistochemical and subcellular localization of Parkin protein: absence of protein in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism patients. Annals of Neurology. 1999;45(5):668–672. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199905)45:5<668::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huynh DP, Scoles DR, Ho TH, del Bigio MR, Pulst SM. Parkin is associated with actin filaments in neuronal and nonneural cells. Annals of Neurology. 2000;48(5):737–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlossmacher MG, Frosch MP, Gai WP, et al. Parkin localizes to the Lewy bodies of Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. The American Journal of Pathology. 2002;160(5):1655–1667. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imai Y, Soda M, Takahashi R. Parkin suppresses unfolded protein stress-induced cell death through its E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(46):35661–35664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S, et al. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nature Genetics. 2000;25(3):302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staropoli JF, McDermott C, Martinat C, Schulman B, Demireva E, Abeliovich A. Parkin is a component of an SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex and protects postmitotic neurons from kainate excitotoxicity. Neuron. 2003;37(5):735–749. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung KKK, Zhang Y, Lim KL, et al. Parkin ubiquitinates the α-synuclein-interacting protein, synphilin-1: implications for Lewy-body formation in Parkinson disease. Nature Medicine. 2001;7(10):1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Gao J, Chung KKK, Huang H, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin-protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(24):13354–13359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240347797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan NC, Salazar AM, Pham AH, et al. Broad activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by Parkin is critical for mitophagy. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20(9):1726–1737. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshii SR, Kishi C, Ishihara N, Mizushima N. Parkin mediates proteasome-dependent protein degradation and rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(22):19630–19640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cookson MR. Parkinsonism due to mutations in PINK1, parkin, and DJ-1 and oxidative stress and mitochondrial pathways. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2(9) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009415.a009415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin SM, Youle RJ. PINK1-and Parkin-mediated mitophagy at a glance. Journal of Cell Science. 2012;125, part 4:795–799. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen D, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;183(5):795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kontos CK, Scorilas A. Molecular cloning of novel alternatively spliced variants of BCL2L12, a new member of the BCL2 gene family, and their expression analysis in cancer cells. Gene. 2012;505(1):153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horowitz JM, Myers J, Stachowiak MK, Torres G. Identification and distribution of Parkin in rat brain. NeuroReport. 1999;10(16):3393–3397. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199911080-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D'Agata V, Grimaldi M, Pascale A, Cavallaro S. Regional and cellular expression of the parkin gene in the rat cerebral cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12(10):3583–3588. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gu W, Abbas N, Lagunes MZ, et al. Cloning of rat parkin cDNA and distribution of parkin in rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2000;74(4):1773–1776. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horowitz JM, Vernace VA, Myers J, et al. Immunodetection of Parkin protein in vertebrate and invertebrate brains: a comparative study using specific antibodies. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2001;21(1):75–93. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubo SI, Kitami T, Noda S, et al. Parkin is associated with cellular vesicles. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;78(1):42–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stichel CC, Augustin M, Kühn K, et al. Parkin expression in the adult mouse brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12(12):4181–4194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pawlyk AC, Giasson BI, Sampathu DM, et al. Novel monoclonal antibodies demonstrate biochemical variation of brain parkin with age. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(48):48120–48128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi P, Golts N, Snyder H, et al. Co-association of parkin and α-synuclein. NeuroReport. 2001;12(13):2839–2843. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200109170-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imai Y, Soda M, Inoue H, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Takahashi R. An unfolded putative transmembrane polypeptide, which can lead to endoplasmic reticulum stress, is a substrate of Parkin. Cell. 2001;105(7):891–902. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarate-Lagunes M, Gu W, Blanchard V, et al. Parkin immunoreactivity in the brain of human and non-human primates: An immunohistochemical analysis in normal conditions and in parkinsonian syndromes. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;432(2):184–196. doi: 10.1002/cne.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Reijden BA, Erpelinck-Verschueren CAJ, Löwenberg B, Jansen JH. TRIADs: a new class of proteins with a novel cysteine-rich signature. Protein Science. 1999;8(7):1557–1561. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.7.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasap M, Akpinar G, Sazci A, Idrisoglu HA, Vahaboğlu H. Evidence for the presence of full-length PARK2 mRNA and Parkin protein in human blood. Neuroscience Letters. 2009;460(3):196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D'Agata V, Zhao W, Pascale A, Zohar O, Scapagnini G, Cavallaro S. Distribution of parkin in the adult rat brain. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):519–527. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esteve-Rudd J, Campello L, Herrero M, Cuenca N, Martín-Nieto J. Expression in the mammalian retina of parkin and UCH-L1, two components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Brain Research. 2010;1352:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.D'Agata V, Zhao W, Cavallaro S. Cloning and distribution of the rat parkin mRNA. Molecular Brain Research. 2000;75(2):345–349. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solano SM, Miller DW, Augood SJ, Young AB, Penney JB., Jr. Expression of alpha-synuclein, parkin, and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 mRNA in human brain: genes associated with familial Parkinson's disease. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47(2):201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cookson MR, Lockhart PJ, McLendon C, O'Farrell C, Schlossmacher M, Farrer MJ. RING finger 1 mutations in Parkin produce altered localization of the protein. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12(22):2957–2965. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hampe C, Ardila-Osorio H, Fournier M, Brice A, Corti O. Biochemical analysis of Parkinson's disease-causing variants of Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin—protein ligase with monoubiquitylation capacity. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15(13):2059–2075. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sriram SR, Li X, Ko HS, et al. Familial-associated mutations differentially disrupt the solubility, localization, binding and ubiquitination properties of parkin. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(17):2571–2586. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Darios F, Corti O, Lücking CB, et al. Parkin prevents mitochondrial swelling and cytochrome c release in mitochondria-dependent cell death. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12(5):517–526. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuroda Y, Mitsui T, Kunishige M, et al. Parkin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis in proliferating cells. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15(6):883–895. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farrer M, Chan P, Chen R, et al. Lewy bodies and parkinsonism in families with parkin mutations. Annals of Neurology. 2001;50(3):293–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hilker R, Klein C, Ghaemi M, et al. Positron emission tomographic analysis of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system in familial parkinsonism associated with mutations in the parkin gene. Annals of Neurology. 2001;49(3):367–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klein C, Pramstaller PP, Kis B, et al. Parkin deletions in a family with adult-onset, tremor-dominant parkinsonism: expanding the phenotype. Annals of Neurology. 2000;48(1):65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maruyama M, Ikeuchi T, Saito M, et al. Novel mutations, pseudo-dominant inheritance, and possible familial affects in patients with autosomal recessive Juvenile Parkinsonism. Annals of Neurology. 2000;48(2):245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.West A, Periquet M, Lincoln S, et al. Complex relationship between Parkin mutations and Parkinson disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics—Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2002;114(5):584–591. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shin C, Manley JL. Cell signalling and the control of pre-mRNA splicing. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2004;5(9):727–738. doi: 10.1038/nrm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(12):1413–1415. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456(7221):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang GS, Cooper TA. Splicing in disease: disruption of the splicing code and the decoding machinery. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8(10):749–761. doi: 10.1038/nrg2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Springer W, Hoppe T, Schmidt E, Baumeister R. A Caenorhabditis elegans Parkin mutant with altered solubility couples α-synuclein aggregation to proteotoxic stress. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(22):3407–3423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]