Abstract

The lipid component of the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes trial (ACCORD-Lipid) was a landmark, publicly-funded trial demonstrating that fenofibrate, when added to statin therapy, was not associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes among patients with diabetes. We performed a cross-sectional study of all articles describing results of ACCORD-Lipid in the news and biomedical literature in the 15 months following its publication. For articles published in biomedical journals, we determined whether there was an association between authors’ conflict of interests (COI) and trial interpretation. We identified 67 news and 141 biomedical journal articles discussing ACCORD-Lipid. Approximately 30% of news and biomedical journal articles described fenofibrate as ineffective, whereas nearly 20% concluded it was effective. Among articles making a recommendation, approximately 50% of news and 67% of biomedical journal articles supported continued fibrate use. Authors with COI were more likely to describe fenofibrate as effective (27.1% vs. 8.9%; relative risk [RR]=3.03, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.22–7.50; P=0.008) and to support continued fibrate use (77.4% vs. 45.8%; RR=1.69, 95% CI, 1.07–2.67; P=0.006). ACCORD-Lipid was described inconsistently in news and biomedical journal articles, possibly creating uncertainty among patients and physicians, and COI were associated with more favorable trial interpretation.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical trials are designed to generate knowledge that informs medical practice. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial tested three approaches to prevention of cardiovascular events among patients with diabetes mellitus, including intensive glycemic control, intensive systolic blood pressure control, and lipid control using fenofibrate in addition to statin therapy (Box 1). None of the strategies were associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes, in spite of sufficient statistical power. However, the implications of the lipid component of the trial, hereafter referred to as ACCORD-Lipid,1 were a subject of particular discussion in the months following its publication in March 2010. And like many landmark clinical trials, its results continue to stimulate debate and discussion today, almost four years later.

BOX 1. Overview of the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD)-Lipid trial design and principal results.

|

There are many reasons why the ACCORD-Lipid results have been scrutinized. First, the overall result of the trial suggested that broad fenofibrate use among patients with diabetes was not associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes. However, subgroup analyses demonstrated that women experienced worse cardiovascular outcomes when compared with men and a non-statistically significant trend towards benefit among patients with high triglyceride and low high-density lipoprotein levels. These results were consistent with subgroup analysis of an earlier landmark trial suggesting fenofibrate may be beneficial in this population.2 Second, despite limited evidence of its clinical benefit, fenofibrate has become a blockbuster drug in recent years, generating sales exceeding $1.1 billion in 2011 and 2012.3,4 Moreover, questions have been raised about the manufacturer’s (i.e., AbbVie, formerly the pharmaceutical division of Abbott Laboratories) decisions to repeatedly reformulate fenofibrate and modify the marketed doses, hindering generic drug makers’ efforts to establish bioequivalence and compete with the proprietary brand.5 Finally, results from all three parts of ACCORD have been closely watched given the $300 million investment made by National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund this large, landmark trial.6

Together the unexpected result of ACCORD-Lipid, the sheer cost of the overall trial, and several pharmaceutical companies’ financial stake in fenofibrate make the ACCORD-Lipid trial an interesting case study that may offer insight into how new evidence is disseminated to patients and physicians. In addition to reading actual trial publications, clinicians rely upon multiple sources that synthesize evidence and offer interpretations of clinical trial findings, including editorials, commentaries, systematic reviews and practice guidelines, to obtain information about clinical trials. All the while, patients and physicians increasingly obtain health information from the news media, particularly online outlets.

Accordingly, we characterized how the results of ACCORD-Lipid were described and interpreted in a cross-sectional analysis of articles published in newspapers and magazines (henceforth described as ‘news’) and the biomedical literature in the 15 months following its original publication. For articles published in the biomedical literature, we also sought to examine whether there was an association between authors’ financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies invested in fenofibrate’s commercial success and their interpretation of the ACCORD-Lipid results; a similar association was previously demonstrated among authors and their respective positions on the cardiovascular safety of the diabetes medication rosiglitazone.7

METHODS

Article Selection and Data Extraction

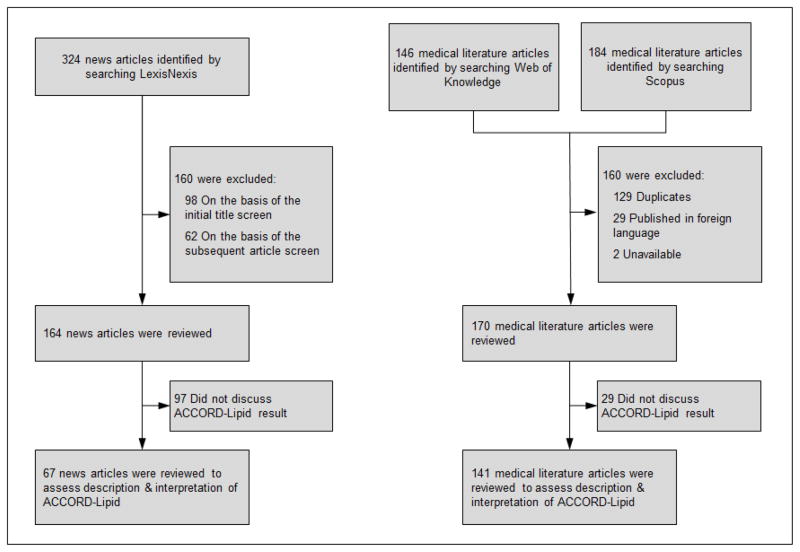

We identified articles from the news and biomedical literature that discussed the findings of ACCORD-Lipid in the 15 months after its original publication on March 14, 2010 (Figure).1 We used LexisNexis Academic (Reed Elsevier; London, England), which indexes articles published in a wide variety of sources, including newspapers and magazines, to identify news articles. We searched for those articles that were published between March 14, 2010 and June 14, 2011 and mentioned fenofibrate or its branded formulations using the following search string: “[body(Tricor) OR body(Trilipix) OR body(fenofibrate)] AND [body(lipid) OR body(cholesterol)]”. We limited our search to articles published in newspapers, newsletters, industry trade press, magazines, non-academic journals and newswires, press releases and scientific materials. Blogs and articles published in online-only publications were excluded, as well as articles published in a language other than English. Two reviewers (NSD and JSR) screened the titles of all articles for relevance, excluding those clearly unrelated to ACCORD-Lipid (e.g., earnings call announcements, articles discussing the status of generic drug manufacturers’ applications). The remaining articles were downloaded for review and classification.

FIGURE.

CONSORT Flow Diagram representing the identification and selection of news articles and biomedical journal articles for study inclusion.

To identify relevant articles published in the biomedical literature, we searched Web of Knowledge (Thomson Reuters; New York, NY), an online citation index, for scientific articles that cited the original ACCORD-Lipid publication and downloaded their complete citation information. In parallel, we performed an identical search in Scopus (Reed Elsevier; London, England), a similar scientific citation index, and merged the two samples before removing duplicates by manual review. Next, the full text of each article, excluding those written in a non-English language, was downloaded for review and classification. Two reviewers (NSD and JSR) classified articles into one of four categories: original article, review, guideline and editorial or commentary.

Article Classification

Each identified article in the news and biomedical literature was allocated to two reviewers, chosen at random from a pool of four (NSD, TC, NDS and JSR). The reviewers assigned three classifications to each article. First, the proportion of the article dedicated to discussion of ACCORD-Lipid was recorded using pre-specified descriptors (Appendix 1); articles without any substantive discussion of ACCORD-Lipid were subsequently excluded from further classification and analysis. Second, the description of ACCORD-Lipid findings was classified as “effective” (i.e., interpreted the results as supportive of fibrate efficacy), “mixed”, or “ineffective” (i.e., interpreted the results as failing to demonstrate fibrate efficacy) (Box 2). Finally, authors’ recommendations for future fibrate use, in light of their interpretation of the ACCORD-Lipid findings, were classified as “supportive” (i.e., recommends fenofibrate use in patients with elevated triglycerides and low high-density lipoprotein or any broader population), “neutral” (i.e., notes insufficient evidence to make a recommendation about fenofibrate use) or “unsupportive” (i.e., states fenofibrate should not be used in efforts to reduce cardiovascular risk); if a recommendation was not made, the article was classified as “no recommendation.”

BOX 2. Criteria used to classify news and biomedical journal articles according to their description and interpretation of the ACCORD-Lipid trial.

| Description of fenofibrate effectiveness in the ACCORD-Lipid trial | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Effective | Emphasizes the absolute reductions in cardiovascular risk noted in the overall result of ACCORD-Lipid or any of its subgroup analyses. Focuses on the changes to surrogate endpoints, such a triglyceride and low density lipoprotein levels, as opposed to clinical endpoints | “Although fenofibrate reduced triglyceride levels, there was only a small difference in mean HDL and no difference between LDL-C between groups, which could help to explain lack of benefit… Those subjects with residual atherogenic dyslipidemia as identified by an increased triglyceride level and low HDL-C had a significant 31% reduction in primary end point”1 |

| Mixed | Emphasizes both the trials’ strengths and limitations. Includes favorable and unfavorable interpretations of ACCORD-Lipid | “No significant differences between the two groups with respect to any secondary outcome was found, although there were some interesting subgroup analyses…. a possible interaction according to lipid subgroup, with a possible benefit for patients with both a high baseline triglyceride (TG) level and a low baseline level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).”2 |

| Ineffective | Views ACCORD Lipid trial as an overwhelmingly negative result given failure to meet primary endpoint. Notes trend towards benefit among patients with high triglyceride and low high-density lipoprotein levels was not significant. | “The results showed no difference between the 2 lipid arms in the primary or any of the secondary outcomes. One can conclude that in a setting of good glycemia, BP, and LDL control, a significant reduction in triglycerides and a small increase in HDL does not reduce CVD events in older patients with well-established diabetes.”3 |

| Recommendation for fibrate use in light of the ACCORD-Lipid trial | Description | Examples |

| Supportive | Any recommendation of fibrate use, either in the subpopulation of patients with high triglyceride and low high-density lipoprotein levels or any broader population | “The subgroup analysis from the ACCORD Lipid study and similar findings support the combination use of statin with fibrates for cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk patients with mixed dyslipidemia”4 |

| Neutral | Notes insufficient evidence to make a recommendation about fenofibrate use or that further studies are required | “These new findings suggest that further studies are needed to establish the effects of fenofibrate in the treatment of both macrovascular and microvascular complications of T2DM, albeit in specific groups”5 |

| Unsupportive | Explains that fenofibrate has no role in cardiovascular risk reduction (n.b., recommendation of fenofibrate for prevention of pancreatitis among patients with very high levels of triglycerides does not preclude) | “The findings of ACCORD, therefore, do not support the use of fenofibrate to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with type II diabetics [sic] who are receiving statin therapy. Moreover, these results emphasize the hazards of assuming that improvements in surrogate end points, such as lipid levels, will translate into reductions in morbidity and mortality.”6 |

When there was a disagreement between the classifications made by the initial two reviewers, the article was randomly assigned to one of the two remaining reviewers, who served as a tiebreaker. Classifications that could not be resolved using this methodology were discussed by all four reviewers together and a consensus classification was made. Initial agreement in article classification was high between two reviewers, ranging from 69% to 81% across the three sources of information; on average, less than 25% of classifications required a third reviewer for a tiebreaker or consensus discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

For biomedical journal articles only, we identified whether their authors had relationships with the manufacturer of fenofibrate (i.e., AbbVie/Abbott Laboratories) or any other pharmaceutical company with a commercial interest in the product (i.e., Astra-Zeneca co-promotes the drug in the U.S.; Fournier Pharmaceuticals initially developed the drug; Solvay subsequently purchased Fournier),8–10 henceforth described as ‘Conflicts of Interest (COI)’. We did not determine if authors of news articles or the physicians quoted in the news stories had COI given the lack of disclosure statements in the news media.

To identify COI, we randomly assigned each biomedical journal article to two reviewers (NSD and TC), who reviewed the disclosure statements in the main publication as well as any supplementary online information. Articles written by authors disclosing any association with AbbVie/Abbott, Astra-Zeneca, Solvay or Fournier, and articles funded by any of these companies, were considered to have COI.

For articles where review of disclosure statements did not identify any COI, we performed additional searches for undisclosed existing relationships, as had been done in prior work.11 Using Scopus, we identified other articles written by each author and published between twelve months prior to and six months after the publication date of the author’s original article discussing ACCORD-Lipid. The disclosure statements associated with these articles were reviewed to identify COI. For editorials, reviews and other articles in our sample with three or fewer authors, we searched each of the authors’ contemporaneous publications; for those with four or more authors, we searched the first and last authors’ publications.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize how ACCORD-Lipid was described and interpreted in news and biomedical journal articles and the prevalence of COI among authors of biomedical journal articles. Subsequently, we used a Fisher’s exact test to examine the association between authors’ descriptions and interpretations of the trial and their COI. Two-tailed P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All analysis was conducted in Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) and JMP 9 (SAS Statistical Institute Inc.; Cary, NC).

RESULTS

News

Our search strategy identified 164 news articles. Reviewers agreed that 97 did not discuss ACCORD-Lipid in sufficient detail for further classification, leaving 67 for review (Figure). Among these 67 news articles, 39 (58.2%) were published in the three months following the publication of ACCORD-Lipid. This trial was the sole focus of 21 (31.3%) news articles, 28 (41.8%) devoted multiple paragraphs, while 18 (26.9%) briefly discussed it. Over one quarter of news articles (n=20; 29.9%) described fenofibrate as ineffective, over half (n=36; 53.7%) as mixed, and 11 (16.4%) concluded it was effective (Table 1 and Box 2). Approximately one third (n=23; 34.3%) of the 67 news articles discussing ACCORD-Lipid made a recommendation about fibrate use in light of the trial’s findings. Among these, 6 (26.1%) were unsupportive of fibrate use, 5 (21.7%) were neutral, noting that there was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation, and 12 (52.2%) were supportive of fibrate use. In addition, among articles making a recommendation, more than three-quarters describing fenofibrate as effective (7 of 11; 77.8%) and nearly half as mixed (5 of 11; 45.5%) were supportive of fenofibrate use (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Description and interpretation of the ACCORD-Lipid trial within news articles and biomedical journal articles published in the 15 months after trial publication.

| News | Biomedical Literature | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| All | All | Review | Editorial/Commentary | Original article | Guideline | |

|

| ||||||

| Articles, No. | 67 | 141 | 70 | 42 | 24 | 5 |

| Proportion of article discussing ACCORD-Lipid trial, No. (%) | ||||||

| Sole focus | 21 (31.3%) | 8 (5.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 7 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Substantial discussion | 28 (41.8%) | 49 (34.8%) | 21 (30.0%) | 19 (45.2%) | 8 (33.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Mentions in passing | 18 (26.9%) | 84 (59.6%) | 48 (68.6%) | 16 (38.1%) | 16 (66.6%) | 4 (80.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Description of fenofibrate effectiveness in ACCORD-Lipid trial, No. (%) | ||||||

| Effective | 11 (16.4%) | 28 (19.9%) | 15 (21.4%) | 4 (9.5%) | 8 (33.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Mixed | 36 (53.7%) | 71 (50.4%) | 36 (51.4%) | 20 (47.6%) | 12 (50.0%) | 3 (60.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Ineffective | 20 (29.9%) | 42 (29.8%) | 19 (27.1%) | 18 (42.9%) | 4 (16.6%) | 1 (20.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Recommendation for fibrate use in light of discussing ACCORD-Lipid trial, No. (%) | ||||||

| Supportive | 12 (17.9%) | 52 (36.9%) | 30 (42.9%) | 10 (23.8%) | 9 (37.5%) | 3 (60.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Neutral | 5 (7.5%) | 13 (9.2%) | 5 (7.1%) | 8 (19.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Unsupportive | 6 (9.0%) | 12 (8.5%) | 5 (7.1%) | 5 (11.9%) | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (20.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| No recommendation | 44 (65.7%) | 64 (45.4%) | 30 (42.9%) | 19 (45.2%) | 14 (58.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

TABLE 2.

Interpretation of the ACCORD-Lipid trial within news articles and biomedical journal articles published in the 15 months after trial publication, stratified by description of fenofibrate effectiveness in the trial.

| NEWS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of fenofibrate effectiveness in ACCORD-Lipid trial | Recommendation for fibrate use made within article, No. (%) | Recommendation for fibrate use in light of discussing ACCORD-Lipid trial, No. (%)* | ||

| Supportive | Neutral | Unsupportive | ||

| Total (N = 67) | 23 (34.3%) | 12 (52.2%) | 5 (21.7%) | 6 (26.1%) |

| Effective (N = 11) | 9 (81.8%) | 7 (77.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Mixed (N = 36) | 11 (30.6%) | 5 (45.5%) | 4 (11.1%) | 2 (5.6%) |

| Ineffective (N = 20) | 3 (15.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| BIOMEDICAL LITERATURE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of fenofibrate effectiveness in ACCORD-Lipid trial | Recommendation for fibrate use made within article, No. (%) | Recommendation for fibrate use in light of discussing ACCORD-Lipid trial, No. (%)* | ||

| Supportive | Neutral | Unsupportive | ||

| Total (N = 141) | 77 (54.6%) | 52 (67.5%) | 13 (16.9%) | 12 (15.6%) |

| Effective (N = 28) | 21 (75.0%) | 19 (90.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Mixed (N = 71) | 47 (66.2%) | 33 (70.2%) | 8 (17.0%) | 6 (12.8%) |

| Ineffective (N = 42) | 9 (21.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (66.7%) |

Proportion calculated only among those articles that made a recommendation about fibrate use.

Biomedical Literature

Our search strategy identified 170 biomedical journal articles. Reviewers agreed that 29 did not discuss ACCORD-Lipid in sufficient detail for further classification, leaving 141 for review (Figure). Of these 141 articles, almost half (70; 49.7%) were reviews, 42 (29.8%) original articles, 24 (17.0%) editorials or commentaries, and 5 (3.6%) guidelines. ACCORD-Lipid was the sole focus of 8 (5.7%), 49 (34.8%) devoted multiple paragraphs to discussion of the trial and 84 (59.6%) mentioned it briefly. Over one quarter of articles (n=42; 29.8%) described fenofibrate as ineffective, half (n=71; 50.4%) as mixed, and 28 (19.9%) concluded it was effective (Table 1 and Box 2). Over half (n=77; 54.6%) of the 141 biomedical journal articles discussing ACCORD-Lipid made a recommendation about fibrate use in light of the trial’s findings. Among these, 12 (15.6%) were unsupportive of fibrate use, 13 (16.9%) were neutral, noting that there was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation, while the majority (52; 67.5%) were supportive of fibrate use. In addition, among articles making a recommendation, the vast majority describing fenofibrate as effective (19 of 21; 90.5%) and as mixed (33 of 47; 70.2%) were supportive of continued fibrate use (Table 2; see Appendix 2 for examples).

Conflicts of Interest

COI were identified for at least one author of 85 of the 141 (60.3%) biomedical journal articles. Over half were disclosed in the main publication (n=50; 58.8%) and 6 (7.1%) in the online material associated with the main publication; the remaining 29 (34.1%) were not disclosed in original publication and were identified through searches of authors’ other contemporaneous publications. Biomedical journal articles in which at least one author had a COI significantly differed in their description and interpretation of the ACCORD-Lipid trial and in their recommendations for continued fibrate use. When compared with articles for which COI were not identified, articles for which COI were identified were significantly more likely to describe fenofibrate as effective (27.1% vs. 8.9%; relative risk [RR]=3.03, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.22–7.50; P=0.008). Similarly, among articles making a recommendation about fibrate use, articles for which COI were identified were more likely to recommend fibrate use when compared with articles for which COI were not identified (77.4% vs. 45.8%; RR=1.69, 95% CI, 1.07–2.67; P=0.006).

DISCUSSION

Our study found that in the 15 months following publication of the NIH-funded landmark ACCORD-Lipid trial, articles in the news and biomedical literature were inconsistent in their description and interpretation of the trial’s results. Despite the conclusive overall finding that fenofibrate did not effectively lower cardiovascular risk, articles discussing the trial offered no clear consensus on the role of fenofibrate for patients with diabetes, as nearly 20% suggested it was effective, while 30% suggested it was ineffective. Even among those that provided a mixed interpretation of the trial’s findings (i.e., noting the trial’s strengths and weaknesses), the authors often went on to recommend fibrate use. The wide variation in the description and interpretation of the trial likely created uncertainty among patients and physicians about the ACCORD-Lipid findings, raising questions about the role news and biomedical journal articles are playing in the dissemination of findings from landmark clinical trials and their prospective use in promoting evidence-based practice.

Given the nuance and complexity of clinical trials, a range of interpretations is often appropriate. However, as our study highlights, such wide variation may be an impediment to evidence-based practice. In today’s clinical environment, where 75 trials and 11 systematic reviews are published every day,12 no practicing physician can be expected to keep up with the growing evidence base. And while not every trial is relevant to every physician, landmark trials and systematic reviews are intended to resolve uncertainties about high impact clinical questions, thereby improving healthcare quality.13 Ensuring the rapid and accurate dissemination of this research requires many steps, and ideally would be complemented by statements from professional societies that are financially independent from medical product manufacturers and can therefore objectively address landmark trials as they are published in order to help patients and physicians place the results in context. Professional societies can take on the role of independent evaluator of clinical trial evidence and provide interpretation to facilitate translation of findings for clinical practice. In this case, neither the American Diabetes Association nor the American College of Cardiology has made such a statement on ACCORD-Lipid.14,15 However, the American Heart Association did issue a Scientific Statement in April 2011 focused on triglycerides and cardiovascular disease, explaining that ACCORD-Lipid did not demonstrate an overall benefit of adding fibrate therapy to statin therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, but that there may be a benefit among the subgroup of patients with high triglyceride and low high-density lipoprotein levels.16 In fact, the Statement concludes that the aggregate data suggest that fibrate monotherapy may be beneficial in patients with high triglyceride levels, low high-density lipoprotein levels, or both.16

Many information sources relied upon by patients and physicians, such as the news media, are not typically peer-reviewed, raising the importance of ensuring that clinical trials, particularly landmark trials with the potential to change practice, are described and interpreted in a consistent manner. Even among biomedical journal articles, most were commentaries or editorials that typically undergo minimal editorial review, or sometimes even no review. Similar to prior research findings that authors with financial relationships with relevant industry are more likely to have a favorable position on the cardiovascular safety of the diabetes medication rosiglitazone,7 we found that authors with financial relationships with companies that manufacture and market fenofibrate were three times more likely to interpret the ACCORD-Lipid trial favorably and nearly twice as likely to recommend continued fenofibrate use.

Ideally, all articles that describe and interpret landmark clinical trials should be written by authors who have no financial stake in the interventions, as those with financial stakes, particularly manufacturing companies, are more likely to report favorable results and conclusions.17 However, relationships with industry are essential to further basic science and clinical research, and many physicians choose to collaborate with industry, making transparency of authors’ relationships with industry critical. Our study found that one-third of the COI we identified were not disclosed in the original publications or their supplementary material and were only identified through our searches of authors’ contemporaneous publications. Biomedical journal editors, as well as editors of news articles, should clearly display COI at the beginning or end of articles so that readers can easily obtain this information during the course of reading and be mindful of the possible influence of these relationships.

There are several limitations of our study to consider. First, we did not include other sources of information that also inform patients and physicians, such as television, scientific conferences, continuing medical education seminars, sales calls from representatives of the pharmaceutical industry, conversations with peers, point-of-care resources, blogs and other online resources. Second, we excluded non-English language articles, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Third, although our cross-sectional approach provides a snapshot of the debate about the ACCORD-Lipid findings in the 15 months following its initial publication, debate and discussion about this trial persists today. Our study illustrates the sentiment about fenofibrate use during this period; however, the long-term interpretation of this trial remains unclear. This 15 month period might also be when controversy and uncertainty should be expected to be greatest, as the field slowly comes to consensus as additional information from the trial becomes known. Fourth, while agreement between reviewers was high, our approach necessitated that articles be classified into discrete categories, which eliminated authors’ caveats and nuances. Finally, it is well established that authors do not consistently disclose all COI,18,19 and despite our extensive search strategy, our study may have underestimated the incidence of such relationships. However, we may also have overestimated COI, identifying relationships in contemporaneous publications that were initiated after the original article was published, although we expect this to be unlikely.

In conclusion, in the 15 months following publication of the NIH-funded landmark ACCORD-Lipid trial, articles in the news and biomedical literature were inconsistent in their descriptions and interpretations of the trial’s results. Despite the conclusive overall finding that fenofibrate did not effectively lower cardiovascular risk for patients with diabetes, many articles in these media interpreted the ACCORD-Lipid trial as demonstrating fenofibrate to be effective and supported its continued use. Authors who had relationships with pharmaceutical companies involved in the manufacture and marketing of fenofibrate were significantly more likely to interpret the trial favorably and to recommend continued use of fenofibrate. Our findings raise questions about the role news and biomedical journal articles are playing in the dissemination of findings from landmark clinical trials and their prospective use in promoting evidence-based practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/support and role of the sponsor: This project was not supported by any external grants or funds. Drs. Krumholz and Ross receive support from Medtronic, Inc. and Johnson and Johnson, Inc. to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting, and from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop methods for post-market surveillance of medical devices. Dr. Krumholz is supported by a National Heart Lung Blood Institute Cardiovascular Outcomes Center Award (1U01HL105270-04). Dr. Ross is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG032886) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program.

Footnotes

Data access and responsibility: Mr. Downing and Dr. Ross had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of interest: Mr. Downing reports that he was formerly a consultant to Moderna. Dr. Krumholz reports that he chairs a scientific advisory board for UnitedHealthcare. Dr. Ross reports that he is a member of a scientific advisory board for FAIR Health, Inc.

Author contributions: Mr. Downing and Drs. Krumholz and Ross were responsible for the conception and design of this work. Mr. Downing and Dr. Ross drafted the manuscript and conducted the statistical analysis. Mr. Downing, Ms. Cheng and Drs. Shah and Ross were responsible for acquisition of data. Dr. Ross provided supervision. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

References

- 1.Effects of Combination Lipid Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(17):1563–1574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2005;366(9500):1849–1861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AbbVie. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];Annual Report on Form 10-K and 2013 Proxy Statement. 2012 Available at: http://www.abbvieinvestor.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=251551&p=irol-reportsannual.

- 4.Abbott Laboratories. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];Annual Report on Form 10-K and 2012 Proxy Statement. 2011 Available at: http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/94/94004/Proxy_Page/AR2011.pdf.

- 5.Downing NS, Ross JS, Jackevicius CA, Krumholz HM. Avoidance of Generic Competition by Abbott Laboratories’ Fenofibrate Franchise. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(9):724–730. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];Questions and Answers: Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Study. 2010 Mar 15; Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/other/accord/q_a.htm.

- 7.Wang AT, Mccoy CP, Murad MH, Montori VM. Association between industry affiliation and position on cardiovascular risk with rosiglitazone: cross sectional systematic review. BMJ. 2010;340:c1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AstraZeneca. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];AstraZeneca and Abbott Extend Relationship to Include Co-Promotion of Trilipix. 2009 Jun 4; Available at: http://www.astrazeneca.com/Media/Press-releases/Article/20090604--AstraZeneca-and-Abbott-Extend-Relationship-to-Include.

- 9.Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];New Drug Application 019304, Label and approval history: Lipidil (fenofibrate) Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/pre96/019304_s000.pdf.

- 10.Bloomberg. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];Solvay to Buy Fournier for as Much as EU1.6 Bullion (Update 4) 2005 Mar 24; Available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aKiXJ38hfMBw&refer=europe.

- 11.Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross J, Keyhani S. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-Five Trials and Eleven Systematic Reviews a Day: How Will We Ever Keep Up? PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(9):e1000326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ioannidis JA. Mega-trials for blockbusters. JAMA. 2013;309(3):239–240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.168095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];Position Statements. Available at: http://professional.diabetes.org/ResourcesForProfessionals.aspx?cid=91471.

- 15.American College of Cardiology. [Accessed January 17, 2014.];Guidelines & Quality Standards. Available at: http://www.cardiosource.org/Science-And-Quality/Practice-Guidelines-and-Quality-Standards.aspx.

- 16.Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al. Triglycerides and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292–2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, Busuioc OA, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012;12:MR000033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Selph SS, Fu R. Conflict of Interest Disclosures for Clinical Practice Guidelines in the National Guideline Clearinghouse. PloS One. 2012;7(11):e47343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okike K, Kocher MS, Wei EX, Mehlman CT, Bhandari M. Accuracy of Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures Reported by Physicians. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(15):1466–1474. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.