Abstract

Background

Peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer (GPC) responds poorly to systemic chemotherapy. Limited published data demonstrate improved outcomes after aggressive locoregional therapies. We assessed the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (HIPEC) in GPC.

Methods

We prospectively analyzed 23 patients with GPC undergoing CRS/HIPEC between 2001 and 2010. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and multivariate Cox regression models identified prognostic factors affecting oncologic outcomes.

Results

CRS/HIPEC was performed for synchronous GPC in 20 patients and metachronous GPC in 3 patients. Adequate CRS was achieved in 22 patients (CC-0 = 17; CC-1 = 5) and median peritoneal cancer index was 10.5. Most patients received preoperative chemotherapy (83 %) and total gastrectomy (78 %). Pathology revealed diffuse histology (65 %), signet cells (65 %) and LN involvement (64 %). Major postoperative morbidity occurred in 12 patients, with 1 in-hospital mortality at postoperative day 66. With median follow-up of 52 months, median overall survival (OS) was 9.5 months (95 % confidence interval 4.7–17.3), with 1- and 3- year OS rates of 50 and 18 %. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.8 months (95 % confidence interval 3.9–14.6). In a multivariate Cox regression model, male gender [hazard ratio (HR) 6.3], LN involvement (HR 1.2), residual tumor nodules (HR 2.4), and >2 anastomoses (HR 2.8) were joint significant predictors of poor OS (χ2 = 18.2, p = 0.001), while signet cells (HR 8.9), anastomoses>2 (HR 5.5), and male gender (HR 2.4) were joint significant predictors of poor progression (χ2 = 16.3, p = 0.001).

Conclusions

Aggressive CRS/HIPEC for GPC may confer a survival benefit in select patients with limited lymph node involvement and completely resectable disease requiring less extensive visceral resections.

Gastric adenocarcinoma is frequently associated with synchronous or metachronous peritoneal dissemination. Positive peritoneal cytology and/or macroscopic peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) are identified in 5–50 % of patients presenting with gastric cancer; especially with serosal involvement by large tumors, extensive lymph node involvement, diffuse infiltrative growth pattern and scirrhous-type reaction of the primary tumor.1–5 Disease recurrence after curative resection of gastric cancer occurs in approximately 25–50 % of patients. Disease recurrence is isolated to the abdominal cavity in approximately 50 % of patients and is responsible for the majority of deaths after curative resection.6–9 Locoregional recurrence may be minimized to less than 20 % by optimizing gastric resection margins, performing adequate D2 or greater extended lymph node dissections or by providing adjuvant radiation to the surgical field after inadequate regional lymph node dissection.10,11 However, the incidence of peritoneal recurrence (10–30 %) is not affected by the extent of gastric resection or adjuvant systemic therapies.

Patients with gastric peritoneal carcinomatosis (GPC) have a poor prognosis, with a median survival of less than 6 months and no long-term survivors.12 Systemic chemotherapy has demonstrated some short-term survival benefit of up to 7–10 months in patients with distant metastatic gastric cancer, but not in the setting of PC.13,14 A number of experts consider cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (CRS/HIPEC) as the standard of care for the treatment of pseudomyxoma peritonei, malignant peritoneal mesothelioma and resectable colorectal carcinomatosis.15–17 However, the role of CRS/HIPEC in GPC remains controversial.18,19 Randomized controlled trials of curative gastrectomy in conjunction with CRS/HI-PEC have demonstrated significant long-term survival benefit and decreased peritoneal recurrence in patients with advanced gastric cancer without visible carcinomatosis.20–26 Although some prospective trials have demonstrated limited improvement in median survival after curative gastrectomy plus CRS/HIPEC for macroscopic GPC, especially in patients with limited peritoneal disease, long-term survival benefit in this setting has been minimal.27–31 We present our institutional experience with CRS/HI-PEC for the management of synchronous or metachronous macroscopic GPC and provide a review of the literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed 23 consecutive patients with GPC who underwent CRS/HIPEC between May 2001 and July 2010 from a prospective database. One patient was lost to follow-up and was excluded from survival analyses. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board. Intraoperatively, volume of disease was quantified by the peritoneal cancer index (PCI).32,33 Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) was performed in accordance with techniques, described by Bao and Bartlett. Completeness of cytoreduction (CC) score assessed adequacy of resection, as follows: CC-0, no visible residual disease; CC-1, residual tumors ≤2.5 mm; CC-2, residual tumors 2.5 mm to 2.5 cm; CC-3, residual tumors ≥2.5 cm.34 A standard institutional protocol for HIPEC was initiated after CRS.35 Using the closed technique, a roller-pump heat exchanger perfusion machine (ThermoChem HT-100, ThermaSolutions, Melbourne, FL, USA) allowed adequate saline flow (>800 ml/min) and a target intraperitoneal tissue temperature of 42 °C. Mitomycin C 30 mg was added to the perfusate initially for 60 min, followed by an additional 10 mg for a further 40 min. Postoperative morbidity was classified according to the Dindo–Clavien grading system.36 For the purposes of analysis, grades 3 and 4 were considered major complications.

Statistical analysis was performed by Stata software, version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). p values <0.05 were considered significant. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death. If a patient did not die, they were censored at the time of their last follow-up. Time to progression was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of tumor recurrence. If a patient did not experience progression or recurrence, they were censored on the date of their last follow-up or death when the cause of death is clearly not related to gastric cancer. When progression or recurrence records were missing and cancer could not be ruled out as a cause for death, these patients were included as having disease progression. Survival times were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. One patient was lost to follow-up and was excluded from survival analyses. Proportional hazards Cox regression was used to examine both univariate and multivariate associations with mortality and progression. In univariate analyses, Bonferroni adjustments were made to p values to account for multiple comparisons. All factors that were examined in univariate analysis were considered for entry into the model for multivariate analysis. Variables were selected for the final multivariate model on the basis of a stepwise selection method with the use of clinical judgment and cumulative knowledge for proper selection of predictors.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Clinical Presentation

The median time interval from initial disease diagnosis until surgical resection at our institution was 5.5 months (range 0.3–58.2 months). The mean age of our patients was 51.5 years, and most patients were women (56.5 %). Most patients presented with synchronous PC (87 %), and almost half of the patients (47.8 %) were symptomatic. Before surgical resection at our institution, 20 patients received chemotherapy (Table 1). The most commonly used drugs included combinations of platinum-based drugs 79 %, fluoropyrimidines 74 %, taxanes 47 %, and anthracyclines 37 %, with one patient each receiving bevacizumab and trastuzumab. The median number of cycles of neoadjuvant therapy was 4 (range 3–12 cycles). Data regarding response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy were not available.

TABLE 1.

Preoperative patient characteristics and presentation (n = 23)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at surgery, year, mean ± SD | 51.5 ± 15 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (range) (n = 21) | 25.2 (16.9–39.3) |

| Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index, median (range)a | 0 (0–5) |

| Preoperative albumin, g/dl, median (range) (n = 19) | 3.9 (1.9–4.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 10 (43.5) |

| Female | 13 (56.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 21 (91.3) |

| Not white | 1 (4.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (4.3) |

| Disease status, n (%) | |

| Synchronous GPC | 20 (87) |

| Metachronous GPC | 3 (13) |

| Prior surgical therapy, n (%) | |

| CRS | 2 (8.7) |

| Chemoperfusion | 1 (4.3) |

| Clinical parameter, n (%) | |

| Symptomatic | 11 (47.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 8 (34.8) |

| Ascites | 3 (13) |

| Bowel obstruction | 2 (8.7) |

| Prior chemotherapy, n (%) (n = 20) | |

| Adjuvant | 1 (4.3) |

| Neoadjuvant | 19 (82.6) |

BMI body mass index, GPC gastric peritoneal carcinomatosis, CRS cryoreductive surgery

Excluding index gastric cancer diagnosis

Operative Characteristics and Pathology

Adequate cytoreduction (CC-0/1) was achieved in 22 patients despite a median PCI of 10.5. The majority of patients underwent total gastrectomy (18 patients), 2 patients had partial gastrectomy, 2 patients did not undergo gastrectomy as a result of extensive carcinomatosis, and 1 patient had previously undergone a total gastrectomy. Median operative time and estimated blood loss were 494 min and 500 ml, respectively. All patients received HIPEC with mitomycin C (98 %). Table 2 demonstrates the distribution of T and N stage for the primary gastric cancer according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition staging system. Pathologic assessment revealed diffuse histology in 15 patients and high-grade tumors in 20 patients. High-grade tumors were defined as those meeting any one of the following histologic criteria, including poor cellular differentiation or the presence of signet ring cells or diffuse histology. Positive lymph nodes, signet ring cells, and perineural/perivascular invasion were seen in 63.6, 65.2, and 65.2 % of patients, respectively (Table 2). D2 lymph node dissections were routinely performed in our patients with GPC. The mean number of lymph nodes collected at the time of gastrectomy was 17, and the mean number of positive lymph nodes was 8.

TABLE 2.

Operative characteristics and pathology (n = 23)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Operative time, min, median (range) (n = 21) | 494 (287–780) |

| Estimated blood loss, ml, median (IQR) (n = 19) | 500 (200–900) |

| Peritoneal cancer index, median (range) (n = 22) | 10.5 (0–29) |

| Completeness of cytoreduction, n (%) | |

| CC-0 | 17 (73.9) |

| CC-1 | 5 (21.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (4.3) |

| Surgical resection, n (%) | |

| Peritoneal stripping | 10 (43.5) |

| Omentectomy | 21 (91.3) |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 7 (30.4) |

| Splenectomy | 13 (56.5) |

| Diaphragmatic resection | 5 (21.7) |

| Hepatectomy | 1 (4.4) |

| Cholecystectomy | 6 (26.1) |

| Low anterior resection | 3 (13) |

| Partial colectomy | 6 (26.1) |

| Small bowel resection | 16 (69.6) |

| Partial gastrectomy | 2 (8.7) |

| Total gastrectomy | 18 (78.3) |

| Ureterolysis | 5 (21.7) |

| Hysterectomy | 5 (21.7) |

| Ostomy | 3 (13) |

| No. of anastomoses, median (range) | 2 (0–5) |

| Location of primary tumor, n (%) (n = 19) | |

| Proximal | 12 (63.2) |

| Mid/distal | 3 (15.8) |

| Diffuse | 4 (21.1) |

| AJCC 7th edition TN stage, n (%) (n = 19) | |

| T2N0 | 1 (5.3) |

| T2N1 | 4 (21.1) |

| T3N1 | 5 (26.3) |

| T2N3 | 5 (26.3) |

| T4N1 | 3 (15.8) |

| T4N3 | 1 (5.3) |

| Histologic classification, n (%) | |

| Intestinal | 7 (30.4) |

| Diffuse | 15 (65.2) |

| Unknown | 1 (4.3) |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | |

| Low grade | 3 (13) |

| High grade | 20 (87) |

| Differentiation, n (%) | |

| Well differentiated | 1 (4.3) |

| Moderately differentiated | 4 (17.4) |

| Poorly differentiated | 18 (78.3) |

| Signet ring cells present, n (%) | 15 (65.2) |

| Perineural/perivascular involvement, n (%) (n = 20) | 15 (65.2) |

| Positive lymph node status, n (%) (n = 22) | 14 (63.6) |

IQR interquartile range, CC completeness of cryoreduction, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer

Postoperative Characteristics

Median intensive care unit and hospital length of stay were 2–20 days, respectively. The most common postoperative complications overall included minor infections (34.8 %), pulmonary complications (30.4 %), and cardiac complications (30.4 %), while major 60-day postoperative morbidity (grade III/IV) occurred in 52.2 % of patients. Of the 7 patients undergoing formal distal pancreatic resection, 2 developed a pancreatic leak. Four patients underwent reoperation for enterocutaneous fistulae, wound, or anastomotic complications. Of the 19 patients with available data, adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 9 (47.4 %) patients. There were no postoperative deaths within 60 days of surgery; however, 1 patient died at postoperative day 66 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Postoperative characteristics (n = 23)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Overall morbidity, n (%) (n = 22) | |

| Minor morbidity | 10 (43.5) |

| Major morbidity | 12 (52.2) |

| Overall mortality, n (%) | |

| 30 day | 0 |

| 60 day | 0 |

| In hospital (day 66) | 1 (4.3) |

| Minor wound infection, n (%) | 8 (34.8) |

| Major wound infection, n (%) | 0 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 5 (21.7) |

| Postoperative, bleeding n (%) | 1 (4.3) |

| Cardiac, n (%) | 7 (30.4) |

| Pulmonary, n (%) | 7 (30.4) |

| Ileus, n (%) | 4 (17.4) |

| Delayed gastric emptying, n (%) | 6 (26.1) |

| Pancreatic leak, n (%) | 2 (8.7) |

| Enterocutaneous fistula, n (%) | 1 (4.3) |

| Anastomotic leak, n (%) | 3 (13) |

| Hospital length of stay, day, median (range) | 20 (9–120) |

| ICU length of stay, d, median (range) (n = 22) | 2 (0–110) |

| Return to OR, n (%) | 4 (17.4) |

| Return to ICU, n (%) | 4 (17.4) |

ICU intensive care unit, OR operating room

Oncologic Outcomes

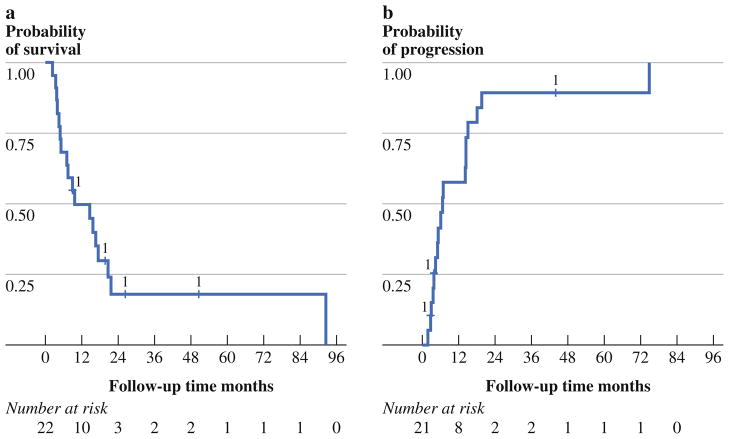

Median follow-up time (based on time to end of study) was 4.4 years (range 9.0 months to 9.9 years). Death occurred in 18 patients and tumor progression occurred in 13 patients. Disease progression involved the peritoneum in 7 patients and occurred systemically in 10 patients. Two patients had either an unknown date of progression or unknown progression status. The median OS was 9.5 months [95 % confidence interval (CI) 4.7–17.3], with 1- and 3-year OS probabilities of 49.6 and 17.9 % (Fig. 1a). The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.8 months (95 % CI 3.9–14.6), with 1- and 3-year PFS probability of 42.8 and 10.7 % (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

a Kaplan–Meier OS curve for patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (n = 22). Median survival was 9.5 months (95 % CI 4.7–17.3), with 1- and 3-year OS probability of 49.6 and 17.9 %, respectively. b Kaplan–Meier curve for time to progression for patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (n = 21). Median time to progression was 6.8 months (95 % CI 3.9–14.6), with 1- and 3-year PFS probability of 42.8 and 10.7 %, respectively

Univariate associations with poor survival were examined for gender, synchronous versus metachronous presentation, symptoms, completeness of cytoreduction, PCI, blood loss, specific visceral resection, number of anastomoses, tumor histology/grade/differentiation, signet ring cell features, lymph node involvement, and postoperative morbidity. On univariate analysis, significant predictors of poor survival included number of positive lymph nodes (p = 0.008) and delayed return of bowel function of >3 weeks (p = 0.02). There was a trend toward poor survival in male patients (p = 0.08), in those undergoing incomplete CC-1 cytoreductive surgery (p = 0.09), in patients with multiple bowel anastomoses (p = 0.16), and in patients with higher estimated blood loss (p = 0.13). In a multivariate Cox regression model, male gender, number of anastomoses, number of positive lymph nodes, and incompleteness of cytoreduction (CC-1) were joint significant predictors of poor survival (χ2 = 18.2; p = 0.001) (Table 4). Significant predictors of poor progression on univariate analysis included signet cells (p = 0.03). There was a trend toward worse progression in men (p = 0.09), higher number of positive lymph nodes (p = 0.07), incompleteness of cytoreduction CC-1 (p = 0.11), and patients with multiple visceral anastomoses (p = 0.12). In a multivariate Cox regression model, signet cells,>2 visceral anastomoses, and male gender were joint significant predictors of poor progression (χ2 = 16.3; p = 0.001) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Multivariate predictors of mortality and poor progression

| Predictor | HR | Comparison group | SE | 95 % CI for HR | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of mortality (χ2= 18.2; p = 0.001) | |||||

| Sex (male) | 6.2 | 4.8 | 1.4–27.9 | 0.016 | |

| No. of positive lymph nodes | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.1–1.4 | 0.003 | |

| No. of anastomoses > 2 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 0.7–10.8 | 0.14 | |

| Completeness of cytoreduction > CC-0 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.6–10.4 | 0.25 | |

| Predictors of progression (χ2 =16.3; p = 0.001) | |||||

| Signet cells | 9.9 | 6.2 | 2.3–35.1 | 0.002 | |

| Visceral anastomoses> 2 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 1.2–24.1 | 0.03 | |

| Sex (male) | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.8–7.6 | 1.48 | |

HR hazard ratio, SE standard error, CI confidence interval

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the EVOCAPE 1 study, patients with GPC generally have advanced T stage, high peritoneal tumor burden, and liver metastases, and they demonstrate a median OS of 3 months after palliative surgery and systemic chemotherapy.12 Randomized trials comparing combination chemotherapy regimens to best supportive care alone for advanced, recurrent, or metastatic unresectable gastric cancer have demonstrated response rates of 25–50 % and median survival of 7–10 months, with no long-term survivors. However, a majority of the patients in these trials had non-peritoneal-based metastatic disease.37–39 The addition of targeted drugs to combination chemotherapy regimens has further improved survival.40,41 However, the response rate of measureable GPC to systemic chemotherapy is only 14–25 %, most likely attributable to poor penetration of systemic chemotherapy across the blood–peritoneal barrier.13,14, 42–44 In patients with isolated GPC, systemic chemotherapy benefits those patients without measurable disease and those with low-grade PC (defined by lack of PC on preoperative imaging, or lack of bowel involvement and minimal ascites on preoperatively imageable disease), as opposed to patients with measureable disease or high-grade PC. This benefit from systemic chemotherapy in patients with nonmeasureable peritoneal disease or low-grade PC is especially evident when combined with gastrectomy and D1/D2 lymphadenectomy, demonstrating median survival of 18–30 months.45 This provides a rationale for aggressive CRS surgery to achieve macroscopic disease clearance and HIPEC to target microscopic disease.

Recent systematic reviews of CRS/HIPEC for gastric cancer with isolated macroscopic PC demonstrate a median survival of 8 months and a 5-year survival up to 13 %. Survival advantage is especially evident after complete cytoreduction in patients with low PCI, demonstrating median survival of 15 months (range 10–43 months) and 5-year survival rate of up to 27 %. This was achieved with morbidity and mortality rates of 22 and 5 %, respectively.18,30 Independent prognostic factors for improved survival after CRS/HIPEC include synchronous PC, complete cytoreduction (CC-0), systemic chemotherapy, no significant postoperative adverse events, surgery at a high-volume center, and low burden of peritoneal carcinomatosis.27–29,31,46–48 In our study, a limited subset of patients demonstrated a modest survival benefit to CRS/HIPEC. Complete cytoreduction (CC-0) was achieved in 74 % of patients and they demonstrated a favorable survival of 15 months, similar to published data. Any amount of macroscopic residual disease after CRS (>CC-0) portends poor survival, probably reflecting the ineffectiveness of currently available chemo-therapeutic regimens in this aggressive malignancy. Although PCI did not correlate with survival in our cohort of patients, the extent of surgery based on the number of visceral anastomoses predicted survival and may be a surrogate for tumor burden and our ability to achieve complete cytoreduction. Additionally, male gender and number of positive lymph nodes were significant independent predictors of poor OS. However, the results of the multivariate analysis should be considered with some caution, given the small sample size in this study.

Our major morbidity rate is higher than previously published series. However, we have reported our 60-day major (grade III/IV) postoperative morbidity rate (52 %), as opposed to most published studies, which have reported 30-day morbidity rates or which have not defined this period specifically. We think that 30-day morbidity does not adequately capture the often delayed complications associated with these complex procedures. In addition, we considered ileus >3 weeks (3 patients) and any readmission within 60 days of surgery (2 patients) as a major morbidity because these factors significantly affect patient quality of life. In light of this modest survival benefit in a small subset of patients and the significant morbidity associated with CRS/HIPEC, rigorous selection criteria and neoadjuvant/adjuvant therapeutic modalities must be considered when contemplating aggressive CRS/HIPEC in this patient population with advanced GPC. Currently at our institution, all patients with T3T4N1 gastric cancer first undergo CT imaging and laparoscopic staging including peritoneal washings. We do not currently offer CRS/HI-PEC to patients with macroscopic PC, except in rare situations where very limited, focal, small-volume disease is encountered and is isolated to the peritoneal cavity. Even in this situation, patients first receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy and preferably should have a disease-free interval of >1 year for metachronous presentation. Patients with microscopic disease in the peritoneal cavity at laparoscopic staging also receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by CRS/HIPEC for stable disease. Ideally, all gastric cancer patients being considered for CRS/HIPEC should be enrolled onto prospective clinical trials. However, until such clinical trials can be implemented, a highly selective approach is recommended.

Neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy demonstrates response rates of up to 79 % at the primary tumor site in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer.49 However, the response rate of peritoneal nodules is only 14–25 %.44 Positive peritoneal cytology is an independent predictor of poor survival after curative gastrectomy, with survival rates similar to patients with gross peritoneal disease. Conversion of positive peritoneal cytology to negative cytology occurs in over 50 % of patients after neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy, and these patients demonstrate significantly improved survival after curative gastrectomy.1,2 Bidirectional chemotherapy, consisting of combination neoadjuvant systemic and intraperitoneal chemotherapy, has been demonstrated to convert positive peritoneal washing cytology to negative in 63 % of patients with advanced gastric cancer, with corresponding ability to increase CC-0 resection.50 However, despite cytologic conversion, long-term survival after curative resection in these patients is rare, and more than two-thirds experience disease recurrence within the peritoneal cavity, which is the major cause of death. The most promising survival outcomes for CRS/HIPEC have been demonstrated in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer without microscopic or macroscopic peritoneal dissemination.17,24–26 In our patient cohort, 83 % of patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy immediately before surgical resection. Conversely, adjuvant chemotherapy was provided to only 9 of 19 patients (47.4 %) with available data. Of the 10 patients who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy, 1 patient died at postoperative day 66, 5 patients had major postoperative morbidity that prevented further therapy, 2 patients had metachronous carcinomatosis for which they received preoperative chemotherapy only, and 2 patients had no documented reason for the lack of adjuvant therapy.

In summary, aggressive CRS/HIPEC may be selectively offered to gastric cancer patients with low peritoneal tumor burden in whom complete cytoreduction can be achieved. In fact, given the limited survival benefit even in this select subgroup of patients, a multidisciplinary protocol-based approach is warranted. CRS/HIPEC may be most beneficial in a prophylactic setting for patients with locally advanced gastric cancer without peritoneal dissemination and possibly those with positive peritoneal cytology that demonstrate favorable response to neoadjuvant systemic or bidirectional chemotherapy.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

David L. Bartlett, Email: bartlettdl@upmc.edu.

Haroon A. Choudry, Email: choudrymh@upmc.edu.

References

- 1.Mezhir JJ, Shah MA, Jacks LM, Brennan MF, Coit DG, Strong VE. Positive peritoneal cytology in patients with gastric cancer: natural history and outcome of 291 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3173–80. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badgwell B, Cormier JN, Krishnan S, et al. Does neoadjuvant treatment for gastric cancer patients with positive peritoneal cytology at staging laparoscopy improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2684–91. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentrem D, Wilton A, Mazumdar M, Brennan M, Coit D. The value of peritoneal cytology as a preoperative predictor in patients with gastric carcinoma undergoing a curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:347–53. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke EC, Karpeh MS, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Laparoscopy in the management of gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1997;225:262–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asencio F, Aguilo J, Salvador JL, et al. Video-laparoscopic staging of gastric cancer. A prospective multicenter comparison with noninvasive techniques. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:1153–8. doi: 10.1007/s004649900559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Angelica M, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Turnbull AD, Bains M, Karpeh MS. Patterns of initial recurrence in completely resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:808–16. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143245.28656.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landry J, Tepper JE, Wood WC, Moulton EO, Koerner F, Sullinger J. Patterns of failure following curative resection of gastric carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:1357–62. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90344-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarz RE, Zagala-Nevarez K. Recurrence patterns after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: prognostic factors and implications for postoperative adjuvant therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:394–400. doi: 10.1007/BF02573875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:236–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muratore A, Zimmitti G, Lo Tesoriere R, Mellano A, Massucco P, Capussotti L. Low rates of loco-regional recurrence following extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:588–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000;88:358–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<358::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preusser P, Wilke H, Achterrath W, et al. Phase II study with the combination etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced measurable gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1310–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.9.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajani JA, Ota DM, Jessup JM, et al. Resectable gastric carcinoma. An evaluation of preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy. Cancer. 1991;68:1501–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911001)68:7<1501::aid-cncr2820680706>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugarbaker PH. New standard of care for appendiceal epithelial neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:69–76. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan TD, Black D, Savady R, Sugarbaker PH. Systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4011–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan TD, Welch L, Black D, Sugarbaker PH. A systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for diffuse malignancy peritoneal mesothelioma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:827–34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugarbaker PH, Yu W, Yonemura Y. Gastrectomy, peritonectomy, and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: the evolution of treatment strategies for advanced gastric cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21:233–48. doi: 10.1002/ssu.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozzetti F, Yu W, Baratti D, Kusamura S, Deraco M. Locoregional treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:273–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.21052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamazoe R, Maeta M, Kaibara N. Intraperitoneal thermochemotherapy for prevention of peritoneal recurrence of gastric cancer. Final results of a randomized controlled study. Cancer. 1994;73:2048–52. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940415)73:8<2048::aid-cncr2820730806>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujimura T, Yonemura Y, Muraoka K, et al. Continuous hyperthermic peritoneal perfusion for the prevention of peritoneal recurrence of gastric cancer: randomized controlled study. World J Surg. 1994;18:150–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00348209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yonemura Y, Ninomiya I, Kaji M, et al. Prophylaxis with intraoperative chemohyperthermia against peritoneal recurrence of serosal invasion-positive gastric cancer. World J Surg. 1995;19:450–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00299188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu W, Whang I, Suh I, Averbach A, Chang D, Sugarbaker PH. Prospective randomized trial of early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy as an adjuvant to resectable gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;228:347–54. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujimoto S, Takahashi M, Mutou T, Kobayashi K, Toyosawa T. Successful intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion for the prevention of postoperative peritoneal recurrence in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:529–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yonemura Y, de Aretxabala X, Fujimura T, et al. Intraoperative chemohyperthermic peritoneal perfusion as an adjuvant to gastric cancer: final results of a randomized controlled study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1776–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu W, Whang I, Chung HY, Averbach A, Sugarbaker PH. Indications for early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy of advanced gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized trial. World J Surg. 2001;25:985–90. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yonemura Y, Kawamura T, Bandou E, Takahashi S, Sawa T, Matsuki N. Treatment of peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer by peritonectomy and chemohyperthermic peritoneal perfusion. Br J Surg. 2005;92:370–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glehen O, Schreiber V, Cotte E, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 2004;139:20–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall JJ, Loggie BW, Shen P, et al. Cytoreductive surgery with intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:454–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Nagendran J, et al. Treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: a systematic review of survival, mortality, and morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:692–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glehen O, Gilly FN, Arvieux C, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: a multi-institutional study of 159 patients treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2370–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugarbaker PH. Successful management of microscopic residual disease in large bowel cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;43(Suppl):S15–25. doi: 10.1007/s002800051093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:359–74. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1247-5_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bao P, Bartlett D. Surgical techniques in visceral resection and peritonectomy procedures. Cancer J. 2009;15:204–11. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181a9c6f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gusani NJ, Cho SW, Colovos C, et al. Aggressive surgical management of peritoneal carcinomatosis with low mortality in a high-volume tertiary cancer center. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:754–63. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, Kleber G, Grothey A, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2903–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gubanski M, Johnsson A, Fernebro E, et al. Randomized phase II study of sequential docetaxel and irinotecan with 5-fluorouracil/ folinic acid (leucovorin) in patients with advanced gastric cancer: the GATAC trial. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:155–61. doi: 10.1007/s10120-010-0553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ajani JA. Optimizing docetaxel chemotherapy in patients with cancer of the gastric and gastroesophageal junction: evolution of the docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil regimen. Cancer. 2008;113:945–55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross P, Nicolson M, Cunningham D, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing mitomycin, cisplatin, and protracted venous-infusion fluorouracil (PVI 5-FU) With epirubicin, cisplatin, and PVI 5-FU in advanced esophagogastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1996–2004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baba H, Yamamoto M, Endo K, et al. Clinical efficacy of S-1 combined with cisplatin for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2003;6(Suppl 1):45–49. doi: 10.1007/s10120-003-0222-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yano M, Shiozaki H, Inoue M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by salvage surgery: effect on survival of patients with primary noncurative gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:1155–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong SH, Shin YR, Roh SY, et al. Treatment outcomes of systemic chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from gastric cancer with no measurable disease: retrospective analysis from a single center. Gastric Cancer. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0182-1. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang XJ, Huang CQ, Suo T, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: final results of a phase III randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1575–81. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1631-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang XJ, Li Y, Yonemura Y. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy to treat gastric cancer with ascites and/or peritoneal carcinomatosis: Results from a Chinese center. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:457–64. doi: 10.1002/jso.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scaringi S, Kianmanesh R, Sabate JM, et al. Advanced gastric cancer with or without peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a single western center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kochi M, Fujii M, Kanamori N, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 and CDDP in advanced gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:781–5. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0126-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yonemura Y, Endou Y, Shinbo M, et al. Safety and efficacy of bidirectional chemotherapy for treatment of patients with peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer: Selection for cytoreductive surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:311–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]