Abstract

Although the current diagnostic manual conceptualizes personality disorders (PDs) as categorical entities, an alternative perspective is that PDs represent maladaptive extreme versions of the same traits that describe normal personality. Existing evidence indicates that normal personality traits, such as those assessed by the five-factor model (FFM), share a common structure and obtain reasonably predictable correlations with the PDs. However, very little research has investigated whether PDs are more extreme than normal personality traits. Utilizing item-response theory analyses, the authors of the current study extend previous research to demonstrate that the diagnostic criterion for borderline personality disorder and FFM neuroticism could be fit along a single latent dimension. Furthermore, the authors’ findings indicate that the borderline criteria assessed the shared latent trait at a level that was more extreme (d = 1.11) than FFM neuroticism. This finding provides further evidence for dimensional understanding of personality pathology and suggests that a trait model in DSM-5 should span normal and abnormal personality functioning, but focus on the extremes of these common traits.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) defines personality disorders (PDs) as categorical entities that are distinct from each other and from normality. However, researchers have highlighted the limitations of this categorical approach and suggested that a dimensional model would provide a viable replacement (Krueger, Skodol, Livesley, Shrout, & Huang, 2007). One alternative dimensional perspective is that PDs represent maladaptive variants of general personality traits (Clark, 2007; Widiger & Samuel, 2005). According to this hypothesis, items from instruments assessing the DSM-IV PD criteria assess the same underlying constructs as general personality inventories, albeit at more extreme levels.

One heavily researched model of general personality is the five-factor model (FFM; McCrae & Costa, 2008), which consists of the five broad dimensions of extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and openness. It has extensive validity support, including evidence concerning behavioral genetics (Yamagata et al., 2006), developmental antecedents (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005), cross-cultural universality (Allik, 2005), and temporal stability (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). Over the past two decades, a body of research has also suggested that the FFM structure is useful for understanding PDs (Widiger & Trull, 2007). Meta-analyses of the literature (Samuel & Widiger, 2008) and reviews of this research (Clark, 2007; Livesley, 2001) have all suggested that there are strong and robust links between the DSM-IV PD and dimensions of normal personality. In addition, much research has demonstrated that instruments assessing personality pathology and those assessing normal personality traits do share common latent dimensions (Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005; O’Connor, 2005). Although this research has demonstrated that PDs and the FFM share a common structure and consistently relate to one another, little research has tested whether PD instruments actually assess the shared traits at more extreme levels than their FFM counterparts. Item-response theory (IRT) is uniquely well suited for making such a comparison because it indicates how items from different measures vary across a common dimension.

IRT (also known as latent trait theory) and the associated analyses differ markedly from classical test theory in that IRT focuses on properties of items, rather than tests (Embretson & Reise, 2000). IRT analyses proceed by aligning items on a latent dimensional trait and estimating how much psychometric information an item provides about the trait using two parameters: alpha and beta. Alpha, referred to as the slope or discrimination parameter, corresponds to the item’s ability to discriminate between individuals and can be analogized to the item’s effectiveness for assessing the underlying trait. Beta corresponds to the level of the latent trait that is required for an individual to endorse a given response with a 50% probability. Within intellectual assessment, beta is often analogized as the item’s difficulty, but within personality and psychopathology assessment it might more accurately be referred to as extremity or severity.

An important product of IRT analyses is the ability to compare items in terms of their provision of information along the latent trait. Feske, Kirisci, Tarter, and Pilkonis (2007) provided an example from personality pathology when they examined the diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD) using IRT. They found that the criteria had comparable alpha parameters, suggesting that each criterion contributed meaningful information for assessing BPD. However, the authors also found that the items displayed more variation in terms of where they provided that information. For example, whereas the criterion assessing affective instability provided information at moderate levels of the construct, the suicidal behavior criterion was notably more extreme (i.e., severe).

An extension of this type of analysis that is particularly useful for the current study is the ability to compare items across different instruments. Specifically, IRT allows items from an FFM instrument and a PD measure to be fit along a single dimension and simultaneously evaluated in terms of where they provide the most information. This comparison tests whether PD criteria and FFM instruments differ in terms of their extremity. If the dimensional hypothesis was supported, one would expect the PD measure to provide more psychometric information than normal personality items at the extreme (i.e., maladaptive) levels of the shared latent trait. Conversely, if the PD criteria and FFM instruments provide information at the same levels of the trait, it would support the notion that differences are qualitative and not solely due to extremity.

In a previous study, we (Samuel, Simms, Clark, Livesley, & Widiger, 2010) provided an initial test of this hypothesis when we compared a measure of the FFM (i.e., the NEO Personality Inventory–Revised [NEO PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992]) to the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology–Basic Questionnaire (DAPP-BQ; Livesley & Jackson, 2009) and the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality-2 (SNAP-2; Clark, Simms, Wu, & Casillas, in press). Although the IRT analyses indicated that the items assessing normal and abnormal personality overlapped in their coverage of the latent traits, the SNAP-2 and DAPP-BQ provided significantly more information than the NEO PI-R at the highest levels. This was supported by statistical comparisons of the average beta (i.e., “extremity”) parameters for each instrument. For example, the items from the SNAP-2 aggression scale obtained a significantly higher beta value than did those from the NEO PI-R agreeableness scale. The most dramatic support came from items on the DAPP-BQ scale labeled suicidal ideation, which were notably more extreme than their counterparts on the NEO PI-R neuroticism scale. These findings suggested that the maladaptive traits assessed by the DAPP-BQ and SNAP represented extreme versions of traits assessed by normal personality instruments.

Nonetheless, findings from this previous study were limited by the fact that all three measures were self-report questionnaires. Whereas self-report questionnaires are commonly used in clinical practice, semistructured interviews are the preferred method of assessing personality disorders (McDermut & Zimmerman, 2005). Thus, replication of these findings using structured interviews to assess the DSM-IV-TR personality disorders would be particularly useful. The findings from Samuel et al. (2010) were also limited by the use of community samples without a notable range of PD pathology. The use of a clinical sample with a substantial prevalence of PDs would allow greater confidence that personality pathology is well represented and distributed in the sample.

A substance-dependent sample is particularly appropriate for this purpose because of the heavy prevalence of personality pathology among treatment-seeking substance users (Ball, 2005; Ball, Rounsaville, Tennen, & Kranzler, 2001; Rounsaville et al., 1998). Although the physiological and psychological effects of substance use are characterized by marked changes in cognitive, emotional, and social functioning that mimic many of the symptoms of personality disorders (Ball, 2005), research has suggested that there are high rates of personality pathology in these samples even when controlling for substance-related symptoms (Rounsaville et al., 1998).

The current study seeks to address limitations of previous research by using IRT analyses to compare items assessing the FFM to the DSM-IV PD diagnostic criteria assigned by a semistructured interview in a large clinical sample with high PD prevalence. Because comparable results were obtained across a variety of PDs by Samuel and colleagues (2010), we chose to examine only one PD as an illustration. This has the advantage of allowing a clear and concise focus and facilitates a more detailed discussion of individual items, which are the explicit focus of item response theory. Given its high prevalence within substance use samples, we considered antisocial PD as the illustrative example, but its reliance on childhood criteria for diagnosis creates a problematic situation in which the FFM traits and PD behaviors are not exhibited contemporaneously. Thus, we chose to focus specifically on borderline personality disorder (BPD) criteria. BPD is a disorder of notable clinical and research interest (Blashfield & Intoccia, 2000) and is among the most prevalent PDs within substance abuse samples and general clinical settings (Zimmerman, Rothschild, & Chelminski, 2005). In addition, previous work has examined BPD using IRT methods, although it has focused specifically on comparing the diagnostic criteria to one another (Feske et al., 2007). Finally, a practical advantage of choosing BPD is that it has a very strong link with FFM neuroticism (e.g., mean weighted correlation of .54 across 18 studies; Samuel & Widiger, 2008), which assists in meeting the assumption of unidimensionality necessary for IRT analyses.

We hypothesized that when placed on a common latent dimension, BPD criteria will provide more psychometric information than FFM neuroticism items at the uppermost levels of the common trait, which has also been referred to as emotional instability (Goldberg, 1993). Furthermore, we hypothesized that the reverse will be true within the normal range. In addition, the beta parameters will be larger for the BPD criteria, indicating that they are more extreme than the FFM items.

METHODS

DATA SOURCES AND ASSESSMENTS

The current study utilized archival data from three previously collected samples of individuals being treated for substance use disorders in which both FFM traits and PD symptoms and diagnoses were available. Three hundred seventy participants were drawn from Rounsaville and colleagues (1998), but 11 were dropped because of incomplete data. One hundred twenty-one were drawn from Carroll and colleagues (2004), and 12 were dropped because of incomplete data. Finally, 41 were drawn from Ball and Cecero (2001) to yield a total combined sample of 509. The total sample was 51% male, with a mean age of 33.4 years. Sixty percent were White, 32% were African American, and 8% were Hispanic.

All participants completed the NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992), which is an abbreviated 60-item measure of five domains of the FFM. Participants were also interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II (SCID-II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997). All studies used careful interviewer training and calibration procedures to ensure reliable and valid diagnoses. PD diagnoses were particularly prevalent in the sample, with antisocial (58%), borderline (33%), and avoidant (18%) the most common. The NEO FFI and the SCID-II are particularly well suited for this analysis because they have extensive validity evidence for assessing the constructs of neuroticism and BPD, respectively.

Because the SCID-II diagnostic criteria utilize a dichotomous, present/absent format, the NEO FFI items were dichotomized so that they could be compared in a straightforward manner; specifically, responses strongly disagree, disagree, and neutral were coded as absent, whereas agree and strongly agree were coded as present. Previous research has indicated that BPD relates strongly with the FFM neuroticism (e.g., Samuel & Widiger, 2008). Nonetheless, in order to ensure that items from each measure were given equal weight, we selected single NEO FFI items that most closely resembled the content of each BPD criteria. In two cases, the most relevant NEO FFI item was from a domain other than neuroticism, as BPD criterion 2 (unstable interpersonal relationships) was thought to most closely relate to an item from the domain of agreeableness and BPD criterion 4 (impulsivity) was most similar to a conscientiousness item.

ITEM RESPONSE THEORY ANALYSES

A fundamental assumption underlying IRT models is that items being analyzed form a unidimensional latent construct. Stout (1990) has argued that what is required for IRT is not the absence of any subfactors, but the presence of a single, dominant factor. Thus, we sought to demonstrate that the underlying trait was essentially unidimensional, meaning that a broad, general dimension underlies all items. Not surprisingly, exploratory factor analyses indicated that the two NEO FFI items drawn from domains other than neuroticism did not fit particularly well and so these items, and their BPD counterparts, were dropped. The resulting 14 items (7 BPD criteria and 7 NEO FFI neuroticism items) were analyzed for unidimensionality using MicroFACT 2.0 software (Waller, 2002). Following Samuel and colleagues (2010), we examined three indicators of unidimensionality, including the ratio of the first to second eigenvalue, the goodness of fit index (GFI), and the root mean square residual (RMSR). The ratio of the first to second eigenvalue was 2.71, the GFI = .94, and the RMSR = .12. While these values do not indicate perfect unidimensionality, they are comparable to values obtained in our studies (e.g., Samuel et al., 2010) and suggest that the items are amenable to IRT analysis. The item parameters were estimated in a two-parameter logistic model using Multilog 7.03 (Thissen, Chen, & Bock, 2003).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the alpha and beta parameters for all items from the SCID-II and NEO FFI. The alpha parameters for all 14 items were at or near 1.0, suggesting that they all provide substantial information about the shared latent trait. Nonetheless, when averaged within each scale, the neuroticism items had a mean alpha value (1.55) that was significantly higher than the BPD items (1.04), F(1, 12) = 13.3, p = .003. This was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with items treated as cases, scale membership as independent variables, and alpha values as the dependent variable. The higher alpha parameters indicate that the NEO FFI items were better able to discriminate among individuals across the latent trait.

TABLE 1.

Alpha and Beta Parameters from Item Response Theory Analysis

| SCID-II Borderline Diagnostic Criteria

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Alpha | SE | Beta | SE | |

| 1 | “Frantic efforts to avoid abandonment” | 1.04 | (0.17) | 0.84 | (0.16) |

| 3 | “Identity disturbance” | 0.95 | (0.16) | 0.98 | (0.19) |

| 5 | “Recurrent suicidal behavior” | 0.96 | (0.19) | 1.84 | (0.32) |

| 6 | “Affective instability” | 0.99 | (0.16) | 0.51 | (0.15) |

| 7 | “Chronic emptiness” | 1.30 | (0.18) | 0.30 | (0.11) |

| 8 | “Difficulty controlling anger” | 0.89 | (0.15) | 0.62 | (0.17) |

| 9 | “Dissociation” | 1.15 | (0.19) | 1.48 | (0.22) |

| Mean | 1.04 | 0.94 | |||

| NEO-FFI Neuroticism Items

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Alpha | SE | Beta | SE | |

| 51 | “I want someone else to solve my problems” | 1.41 | (0.19) | 0.88 | (0.12) |

| 26 | “I feel completely worthless” | 1.72 | (0.20) | 0.14 | (0.09) |

| 41 | “I get discouraged and feel like giving up” | 1.82 | (0.20) | −0.15 | (0.08) |

| 21 | “Feel tense and jittery” | 1.77 | (0.20) | 0.46 | (0.09) |

| 6 | “Feel inferior to others” | 1.17 | (0.17) | 1.13 | (0.17) |

| 36 | “I get angry at the way people treat me” | 1.04 | (0.15) | 0.25 | (0.13) |

| 11 | “When under stress, I feel like I’m going to pieces” | 1.89 | (0.24) | −0.16 | (0.08) |

| Mean | 1.55 | 0.36 | |||

More relevant to the hypotheses of the current study are the beta parameters that index the location along the latent trait where the item is providing the most psychometric information. These are presented in units of theta, which roughly correspond to z scores within a normal distribution (Embretson & Reise, 2000). The beta values for the BPD criteria were all above zero, with criterion 5 (“recurrent suicidal behavior”) garnering a value of 1.84. This beta value indicates that only individuals with a particularly high level of the latent trait are likely to endorse the item. In contrast, a few of the NEO FFI items were below zero, including item #41 (“Sometimes I get discouraged and feel like giving up”). The average beta value was .94 for the BPD items and .36 for the neuroticism items. While a one-way ANOVA indicated that this difference fell short of statistical significance, F(1, 12) = 4.2, p = .062, this is perhaps misleading because the items, rather than the participants, served as cases. Thus, statistical power was based on the “sample” of 14 items rather than 509 participants. To avoid this, we converted the means and standard deviations to Cohen’s d and the effect size for the difference was 1.11, which is considered large (Cohen, 1992). This indicates that the BPD items are more extreme than the neuroticism items.

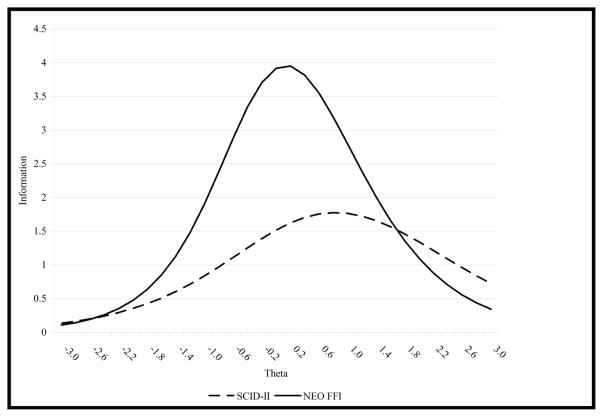

Another result of interest is how the item information curves (IICs), which show the psychometric information that each item provides at all levels of the latent trait, compare across instruments. We summed these IICs separately for the neuroticism and BPD items, and the resulting curves are presented in Figure 1. The Multilog software provides an estimate of the psychometric information at levels of theta ranging from −3.0 to 3.0, at intervals of 0.2. Thus, the mean item information values were tested between the instruments at each interval using a one-way ANOVA. This allowed for a statistical comparison at each interval of theta to determine whether scales were providing different levels of information. The results indicated that the NEO FFI neuroticism curve was significantly higher than the BPD curve from −1.0 to 1.0. Additionally, the BPD curve was significantly higher at the most extreme point examined (i.e., 3.0). This suggests that while the NEO FFI provides greater psychometric information at moderate levels of theta, the BPD criteria provide more information at the uppermost range of the trait.

FIGURE 1.

Mean information curves for SCID-II borderline PD and NEO FFI neuroticism.

DISCUSSION

Compelling evidence indicates that normal personality traits share a common structure (O’Connor, 2005) and maintain predictable relationships with the DSM-IV PDs (Samuel & Widiger, 2008). Nonetheless, few studies have reported that PDs represent extreme variants of normal personality traits (e.g., Samuel et al., 2010). The current study extended previous research by using a clinical sample with high levels of PDs diagnosed using a semistructured interview and found that BPD criteria provided information at a higher level than NEO FFI neuroticism items. As hypothesized, the neuroticism items provided more information at moderate (i.e., normal) ranges of the latent trait, while the BPD criteria provided more information at the most extreme (i.e., maladaptive) ranges.

In fact, the current findings provided even stronger support for the dimensional hypothesis. Our previous study (Samuel et al., 2010) demonstrated that although the self-reported SNAP-2 and DAPP-BQ items were more extreme than those from the FFM, they also displayed a great deal of overlap. In contrast, the current study found that the BPD criteria assessed via interview were consistently more extreme than the neuroticism items and that the overall effect size for this difference was large (d = 1.11). This suggests that the differentiation between normal and abnormal personality increased when the latter was measured via a semistructured interview and provides further evidence to support the idea that borderline PD can be conceptualized as a maladaptive, extreme manifestation of neuroticism.

The explanation for this finding is likely due to the behavioral specificity of the SCID-II diagnostic criteria relative to the SNAP-2 and DAPP-BQ items. Whereas the SCID-II items were designed explicitly to assess the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, both the SNAP-2 and DAPP-BQ were developed to provide measurement of more trait-like representations of personality pathology. Notably, the most dramatic difference identified by Samuel and colleagues (2010) was for the DAPP-BQ’s self-harm scale. The items on the self-harm scale, in contrast to other scales on the instrument, were also quite behaviorally specific because they assess behaviors related to suicide and self-injury.

The results of the current study also can provide information about the assessment of borderline PD offered in DSM-IV. The criteria varied substantially in terms of where along the latent trait they provided the most psychometric information, with beta values ranging from .30 (chronic emptiness) to 1.84 (recurrent suicidality). This suggests that individuals with moderate levels of the latent trait are likely to endorse feeling empty inside, whereas the endorsement of suicidality and self-harm indicates a substantially higher level of the latent trait. These values are also relatively consistent with a previous study that used IRT to examine the DSM-III-R borderline criteria (Feske et al., 2007). Feske and colleagues also found that the suicidal behavior criterion was among the most extreme and only the fear of abandonment had a higher beta parameter. In sum, the current findings suggest that the borderline criteria vary in terms of the location along the latent trait where they provide the most psychometric information.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The current study addressed the primary limitations of a previous study that used IRT to compare measures of normal and abnormal personality. In order to provide a clear and concise picture, we intentionally focused on only one PD. We chose BPD as the illustration because of its prevalence within the sample and historical clinical and research interest. Although previous findings do not suggest that this effect is specific to BPD, future research that continues to employ IRT methodologies with other PDs is warranted. This would be particularly useful for specific PDs, such as schizotypal, for which there is vigorous debate as to how it fits into dimensional models of personality (e.g., Watson, Clark, & Chmielewski, 2008).

Additionally, the current study concerned a sample of individuals with primary substance abuse diagnoses. Although significant levels of PD pathology were present, their manifestation or assessment might be altered by active addiction (Ball, 2005). Nonetheless, it should be noted that Rounsaville and colleagues (1998) found that individuals with BPD diagnoses showed similar clinical profiles regardless of whether their symptoms were related to substance use. Of particular relevance to the current findings, those groups did not differ on neuroticism scores. Although this suggests that the current findings might not be influenced by substance diagnoses, replication within additional clinical samples would be useful.

CONCLUSIONS

The current findings indicate that the diagnostic criteria for borderline PD provide information at higher levels of a latent trait shared with normal-range neuroticism. This result buttresses the idea that the DSM-IV PDs can be conceptualized as maladaptive, extreme variants of the personality traits described by the FFM. This evidence supports a dimensional understanding of PD and is particularly relevant to ongoing discussions regarding the potential implementation of such a model within DSM-5. In particular, it suggests that the DSM-5 can and should incorporate dimensions that extend from the basic science foundation of normal personality description. Furthermore, our findings indicate that a fundamental priority of a DSM-5 trait model should be to ensure that it adequately accounts for the extreme variants of the trait dimensions.

Acknowledgments

For this work, Dr. Samuel was the recipient of the Gunderson Young Investigators Award from the Association for Research on Personality Disorders for 2011. Research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA10012, RO1 DA05592, K12 DA00617, K05 DA00457, R01 DA10679, K05 DA00089, and P50 DA09241) and from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (K20 AA00143). Writing of this article was supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Allik J. Personality dimensions across cultures. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:212–232. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. rev. [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA. Personality traits, problems, and disorders: Clinical applications to substance use disorders. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Cecero JJ. Addicted patients with personality disorders: Traits schemas, and presenting problems. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15:72–83. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.1.72.18642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Rounsaville BJ, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. Reliability of personality disorder symptoms and personality traits in substance-dependent inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:341–352. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashfield RK, Intoccia V. Growth of the literature on the topic of personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:472–473. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter T, Shi J, Rounsaville BJ. Efficacy of Disulfiram and cognitive behavior therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorder: Perennial issues and an emerging reconceptualization. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:227–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Simms LJ, Wu KD, Casillas A. Manual for the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP-2) Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item response theory for psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Feske U, Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Pilkonis PA. An application of item response theory to the DSM-III-R criteria for border-line personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:418–433. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Skodol AE, Livesley WJ, Shrout PE, Huang Y. Synthesizing dimensional and categorical approaches to personality disorders: Refining the research agenda for DSM-V Axis II. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16(Suppl 1):S65–S73. doi: 10.1002/mpr.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ. Conceptual and taxonomic issues. In: Livesley WJ, editor. Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment. New York: Guilford; 2001. pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jackson D. Manual for the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology—Basic Questionnaire. Port Huron, MI: Sigma Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF, Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: An integrative hierarchical approach. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;88:139–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. The five factor theory of personality. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of personality. 3. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- McDermut W, Zimmerman M. Assessment instruments and standardized evaluation. In: Oldham J, Skodol A, Bender D, editors. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of personality disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2005. pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor BP. A search for consensus on the dimensional structure of personality disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:323–645. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR, Ball SA, Tennen H, Poling J, Triffleman E. Personality disorders in substance abusers: Relation to substance use. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:87–95. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199802000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Simms LJ, Clark LA, Livesley WJ, Widiger TA. An item response theory integration of normal and abnormal personality scales. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2010;1:5–21. doi: 10.1037/a0018136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1326–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout WF. A new item response theory modeling approach with applications to unidimensionality assessment and ability estimation. Psychometrika. 1990;55:293–325. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Chen WH, Bock D. Multilog 7.03. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Waller NG. WinMFact 2.0. Minneapolis, MN: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Chmielewski M. Structures of personality and their relevance to psychopathology: II. Further articulation of a comprehensive unified trait structure. Journal of Personality. 2008;76:1485–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Samuel DB. Diagnostic categories or dimensions: A question for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:494–504. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist. 2007;62:71–83. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata S, Suzuki A, Ando J, One Y, Kijima N, Yoshimura K, et al. Is the genetic structure of human personality universal? A cross-cultural twin study from North America, Europe, and Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:987–998. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1911–1918. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]