Abstract

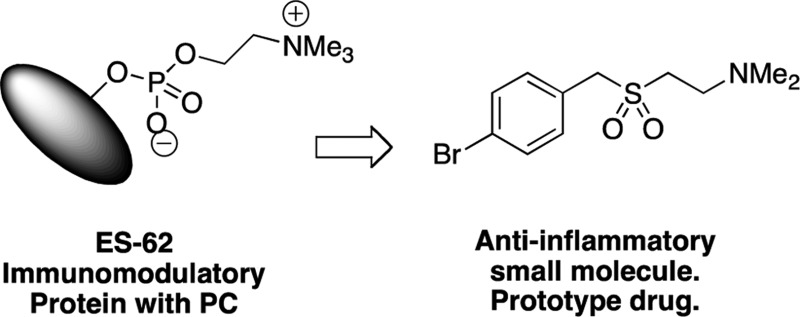

In spite of increasing evidence that parasitic worms may protect humans from developing allergic and autoimmune diseases and the continuing identification of defined helminth-derived immunomodulatory molecules, to date no new anti-inflammatory drugs have been developed from these organisms. We have approached this matter in a novel manner by synthesizing a library of drug-like small molecules based upon phosphorylcholine, the active moiety of the anti-inflammatory Acanthocheilonema viteae product, ES-62, which as an immunogenic protein is unsuitable for use as a drug. Following preliminary in vitro screening for inhibitory effects on relevant macrophage cytokine responses, a sulfone-containing phosphorylcholine analogue (11a) was selected for testing in an in vivo model of inflammation, collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). Testing revealed that 11a was as effective as ES-62 in protecting DBA/1 mice from developing CIA and mirrored its mechanism of action in downregulating the TLR/IL-1R transducer, MyD88. 11a is thus a novel prototype for anti-inflammatory drug development.

Introduction

Parasitic helminths infect up to one-third of the global population1 due to having evolved numerous strategies to balance their survival with that of the host. One mechanism employs secretion of molecules that subtly modulate the host immune response (review ref (2)) to prevent clearance of the parasite without leaving the host vulnerable to opportunistic infections. An understanding of the molecular aspects of this mechanism has been approached through characterization of molecules such as ES-62, a protein discovered in the secretions of the rodent filarial nematode Acanthocheilonema viteae.(3) ES-62 has a range of immunomodulatory effects, many of which involve subversion of TLR4 signaling to induce an anti-inflammatory immunological phenotype.4−6 The molecule has therefore been studied for its therapeutic potential in human diseases associated with aberrant inflammation such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and has been found to be protective in the mouse model of RA, collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), via targeting of pathogenic pro-inflammatory cytokines, in particular IL-17 and IFNγ.7−9

As a tetrameric protein of ∼240 kDa (review ref (10)), ES-62 is immunogenic and hence unsuitable for use as a drug. However, key anti-inflammatory activities are associated with its post-translational glycosylation and subsequent esterification by phosphorylcholine (PC; review ref (11)). Thus, the development of low molecular weight, nonimmunogenic, PC-based derivatives demonstrating ES-62-like biological properties might offer a better approach to drug discovery. Indeed, we have previously found that short synthetic peptides containing PC-esters of tyrosine as well as PC-containing glycosphingolipids replicate some of the immunomodulatory properties of ES-62 in vitro12−15 (and unpublished results). Here, we describe the design and synthesis of a library of novel small molecule analogues (SMAs) related to PC and provide proof of concept in the in vivo CIA model that such compounds can be active against inflammatory diseases like RA for which improved drugs are sought.

Initially, the SMAs were screened in vitro to determine their effect on pro-inflammatory cytokines, promoting Th1 (IFNγ)/Th17 (IL-17) responses that are secreted by macrophages in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The screening strategy was chosen, not only because of the pathogenic roles ascribed to Th1/Th17 polarizing cytokines in RA but also because TLRs are highly expressed by fibroblasts and macrophages in the synovium, and synovial expression of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 is further upregulated by IL-17 (in an IL-1β and IL-6-dependent manner) in CIA.16 Indeed, recent studies suggest that elevated TLR2 levels contribute to the spontaneous release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by synovial tissues.17 Moreover, production of pro-inflammatory chemokines, cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinases, as well as promotion of angiogenesis and cellular invasion18 and also decreases in matrix biosynthesis,19 can be stimulated by triggering of TLRs by PAMPs or endogeneous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that are present in synovial tissue of patients (e.g., TLR2, gp96, Snapin; TLR4, HSP22, tenascin-C). It has thus been proposed that such aberrant TLR signaling drives the chronic inflammation characteristic of RA (reviews refs (20−22)). Collectively, these data have contributed to the identification of TLRs as therapeutic targets in inflammatory disease.23 Hence our previous findings that ES-62 exerts its anti-inflammatory effects at least in part by subverting TLR4 signaling to suppress TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 responses suggests this screening approach for novel RA-targeted drugs is appropriate.4,5 Thus, following the in vitro screen, we selected one of the molecules with properties most similar to ES-62, a sulfone (11a) (termed S3 in UK Patent Application No. 1214106.5) for testing in the CIA model.

Results

PC Conjugated to Bovine Serum Albumin (PC-BSA) Mimics ES-62 in Suppressing IL-17 and IFNγ Responses in CIA

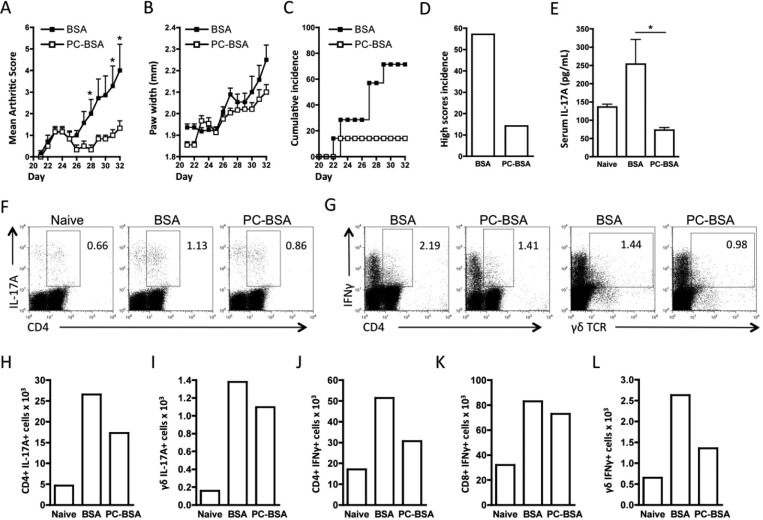

RA has been proposed to exhibit a Th1/Th17 phenotype of autoimmune inflammation, and we have recently shown that ES-62 suppresses both IFNγ and IL-17 production in CIA. While we previously showed that the parasite product modulates Th1 responses by suppression of their priming by dendritic cells (DC24), we found that its protective effects against pathogenic IL-17 responses reflect suppression of a cellular network involving DC, Th17, and γδ T cells.9 Therefore, to address the therapeutic potential of PC-based SMAs of ES-62 in arthritis, we first determined whether a PC-conjugated protein, PC-BSA, could suppress Th1/Th17 responses in CIA. Analysis of its effects (relative to BSA) confirmed and extended our previous findings using PC-ovalbumin (OVA)8 in that PC-BSA suppressed the severity of disease in terms of articular score (Figure 1A) and hind paw width (Figure 1B) as well as reducing incidence of pathology (Figure 1C), especially that pertaining to high articular score (Figure 1D; score ≥4). Also, as with ES-62, PC-BSA reduced the serum levels of IL-17 (Figure 1E), and this was reflected by reduced percentages and numbers of IL-17-producing CD4+ and γδ T cells stimulated with PMA/ionomycin ex vivo (Figure 1F,H,I). Similarly, and also as observed with ES-62, PC-BSA suppressed IFNγ production by CD4+, CD8+, and γδ T cells (Figure 1G,J–L). Collectively, these data suggested that PC-based SMAs could be a suitable starting point for the development of novel anti-inflammatory drugs for RA.

Figure 1.

PC-BSA protects against CIA and targets IL-17 and IFNγ responses. Arthritis scores (BSA, n = 7; PC-BSA, n = 6 (A)) and hind paw width (B), expressed as mean scores ± SEM for BSA- or PC-BSA-treatment groups where n = number of individual mice exposed to collagen and disease incidence (C,D), indicated by the % of mice developing a severity score ≥2 (C) or ≥4 (D). Serum IL-17 levels are plotted as mean values of triplicate IL-17 analyses of serum from individual mice (naïve, n = 3; BSA, n = 6; PC-BSA, n = 6 (E)). (F,G) Exemplar plots of gating strategy of intracellular IL-17 and IFNγ expression by DLN (draining lymph node) cells pooled from BSA- and PC-BSA-treated mice with CIA show CD4 or γδ expression on the x-axis versus cytokine expression on the y-axis, with the relevant % cytokine positive cells annotated. The numbers of cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells (H,J), γδ T cells (I,L), and CD8+ T cells (K) present in the pooled DLN cells from the naïve (not exposed to collagen), BSA, and PC-BSA groups are shown. For statistical analysis, *p < 0.05.

Molecule Design and Synthesis

Our previous work had shown that PC alone13,14 and PC esters of short peptides (unpublished results) and lipids12,15 could reproduce some of the actions of ES-62. However both the size and/or the lability of these compounds suggested that they would not be appropriate as drugs. Moreover, PC esters are known to have a wide range of biological actions, and selectivity would be important for any new drug. A potential solution to these problems is provided by the use of isoesters of the naturally occurring phosphate ester, in which the alkylamino chain and a tetrahedral analogue of the phosphate are included. On the basis of the structure of one of the short peptides, which contained PC-tyrosine, a simple structure was adopted that removed the labile phosphate esters and replaced them with phosphonates, sulfones, sulfonamides, and carboxamides.

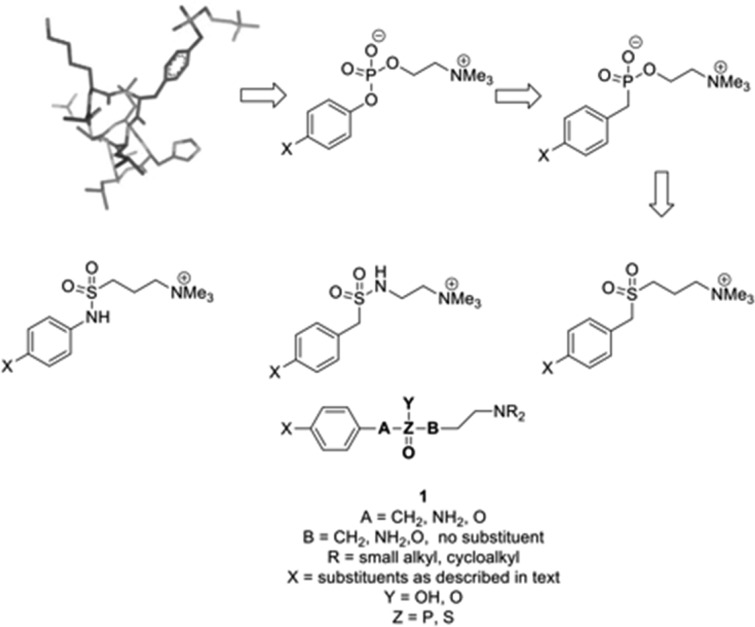

Compound Design

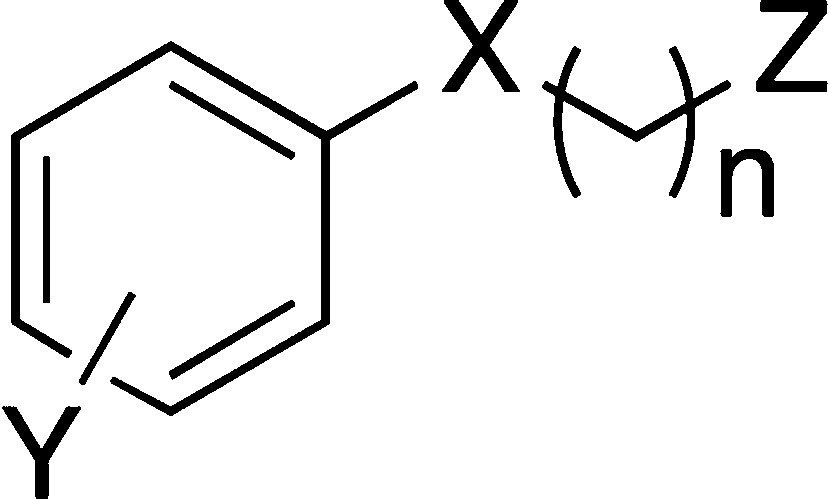

The first series of target compounds was the analogous phosphonates. Choline phosphonates, like phosphates, are zwitterionic and likely to have limited cellular penetration. To obtain monocationic small molecule analogues, therefore, the corresponding sulfones and sulfonamides were included. In place of the peptide backbone, small substituents of differing electronic and steric properties were included in the benzene ring, leading to a generic structure (1) in which this substituent, the methylene chain length, and the substituted amino group could be varied (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Design of small molecule analogues (SMAs) of ES-62 based upon a tyrosyl-phosphoryl choline peptide.

Sulfones have been used in medicinal chemistry principally in peptidomimetics where they link amino acid-like components to give transition state analogues25 and activate alkenes to Michael addition in irreversible inhibitors.26,27 Cathepsin C is an anti-inflammatory target for which vinyl sulfone containing inhibitors have been described.28 Away from the peptide field, sulfones have featured in inhibitors of terpenoid biosynthesis in farnesyl diphosphate mimetics.29 It has also been shown that sulfone and sulfonamide analogues of fosmidomycin are inactive compared with the parent compound; in that case, the loss of the negative charge was considered to be significant.30 The closest structural relatives to the compounds described in this paper can be found in the patent literature, but most are arylsulfones in which the sulfone group is directly attached to the aromatic ring,31,32 unlike the new compounds described here in which there is a methylene group between aromatic ring and sulfonyl group. Sulfonamides have featured in anti-inflammatory compounds as benzensulfonamides in COX-2 inhibitors,33 and some recent studies have included N-alkyl or aryl substituents. Thus the indole-based PLA2 inhibitors34,35 contain N-alkyl sulfonamides within highly hydrophobic structures. A similar substructure is found in some N-dialkylsulfonamide-containing H4 receptor antagonists.36

Synthetic Methods

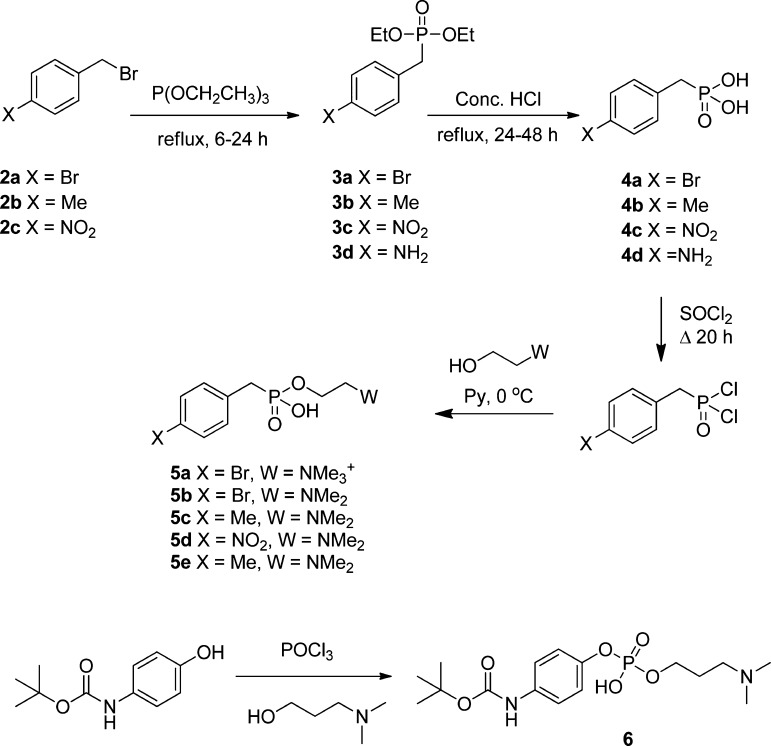

Benzylic Halides to Phosphonates to PC Related Derivatives

Phosphonic acid precursors were prepared from the corresponding benzyl bromides (2a–2c) by the Arbuzov reaction, hydrolysis of the phosphonate esters (3a–3d) to give the corresponding phosphonic acids (3a–3d), activation using thionyl chloride, and finally esterification with choline or an appropriate analogue to give the target compound (Scheme 1, 5a–5e). A phosphate was prepared from the corresponding phenol by phosphorylation with phosphoryl chloride and coupling with choline iodide (Scheme 1, 6).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Phosphorus-Containing SMAs.

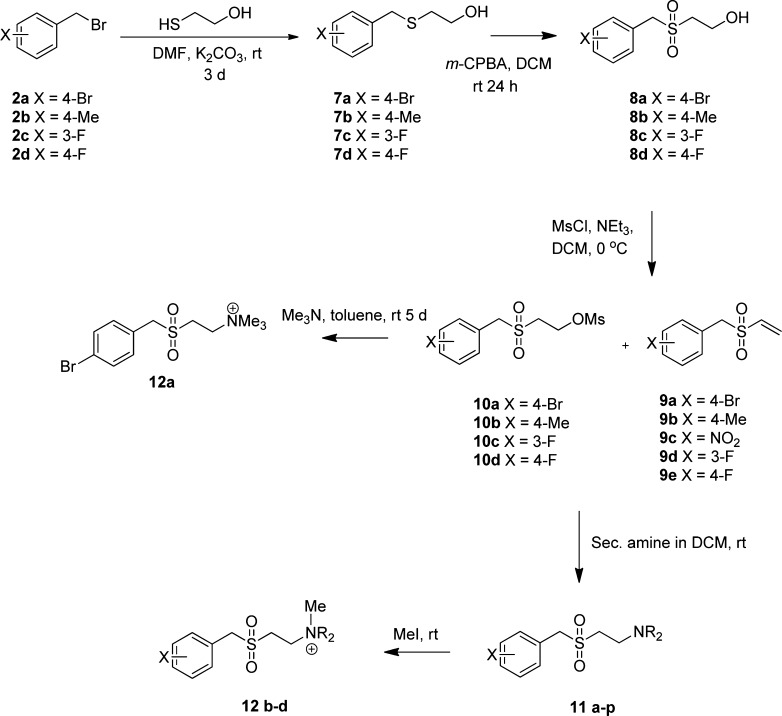

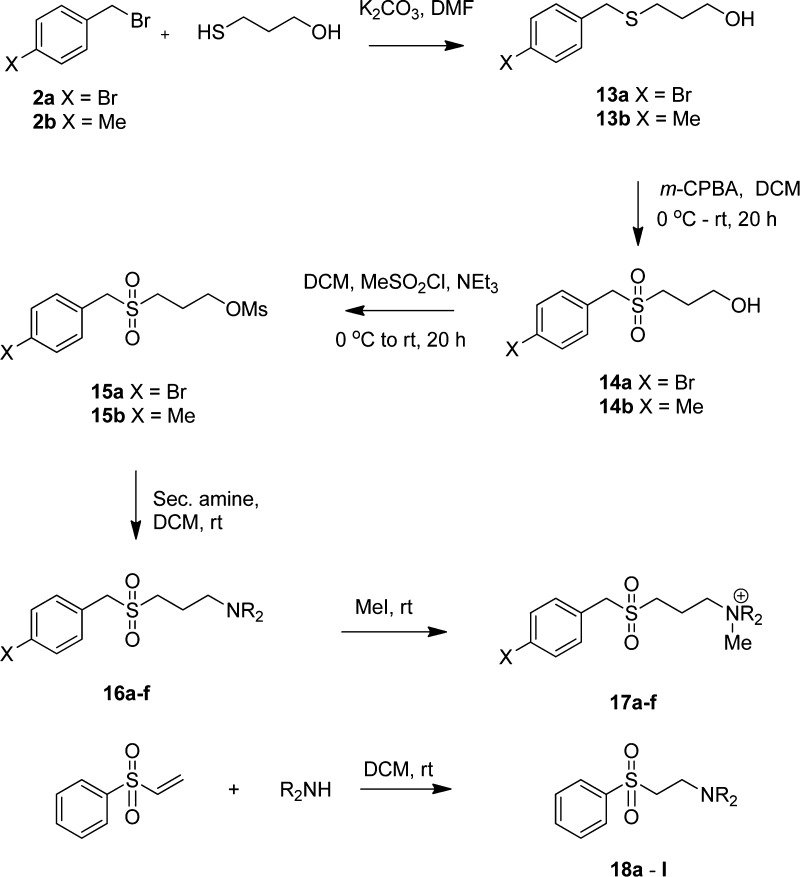

Benzylic Halides to Alkyl Sulfides Followed by Oxidation to Give Sulfones

Sulfones were prepared from the relevant benzylic halide by alkylation of either 2-thioethanol or 3-thiopropanol followed by oxidation of the thioethers (7a–7d, 13a,b, Schemes 2 and 3, respectively) to give the sulfones (8a–8d, 14a,b). Mesylation in the case of the ethyl derivatives afforded a mixture of the vinyl sulfones (9) and the mesylates (10), which was used without separation to react with the appropriate secondary amine to give a series of the required SMAs (11a–11p, 17a–17f). The exact proportions of the vinyl sulfone and mesylate were typically 70–80% vinyl sulfone depending upon substituent and batch. If the reaction time was 48 h or longer, only vinyl sulfone was obtained. This synthetic step was not optimized because both vinyl sulfone and mesylate afforded the same product under equivalent conditions in the following steps. The corresponding quaternary salts (12b–12d) were obtained by alkylation with methyl iodide. For the propyl derivatives in which elimination does not occur under mild conditions, substitution of the mesylate directly afforded the required SMAs.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Aminoethylsulfones.

Secondary amines were Me2NH, pyrrolidine, and morpholine. Substituents X and R of compounds evaluated are given in the tables.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Aminopropylsulfones and Phenyl Sulfones.

Secondary amines were Me2NH, pyrrolidine, and morpholine. Substituents X and R of compounds evaluated are given in the tables.

A third series of phenylsulfones (Scheme 3, 18a–18l) with shorter length than the foregoing compounds was prepared by addition of the appropriate amine to phenylvinylsulfone.

Sulfonamides

Benzyl sulfonamides were simply prepared from the relevant sulfonyl chloride and amine under standard conditions (Scheme 4, 19a–19aa). Arylamino sulfonamides (21a–21p) were prepared from the vinyl sulfonamide (20a–20e) of the appropriate aniline or benzylamine.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Sulfonamides.

Substituents X and R of compounds evaluated are given in the tables. (19) is referred to as the CSN type, (21) as the CNS type, and (23) as the NSC type in the text.

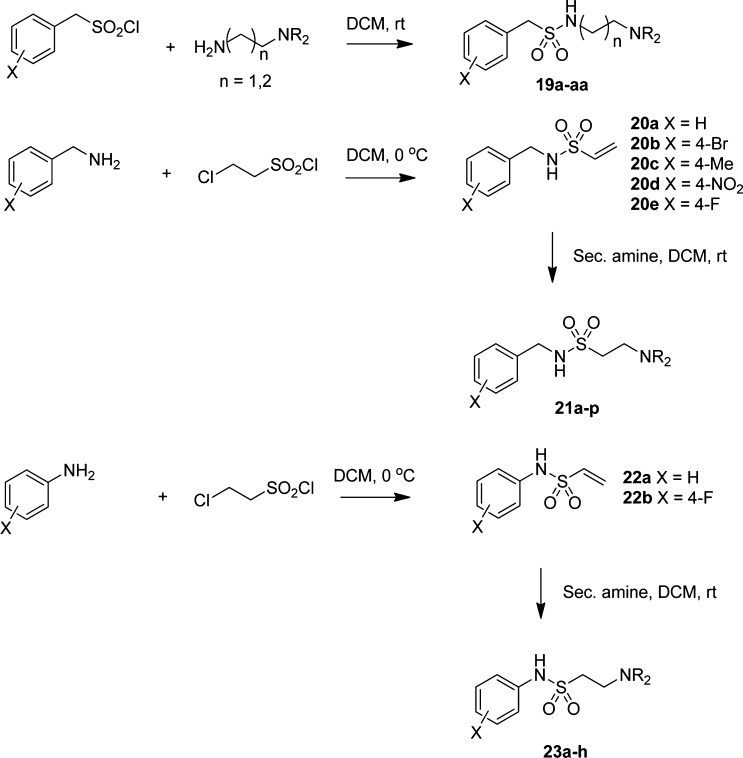

Carboxamides (24a–24d, 25a–25d) were prepared by acylation of the appropriate amine with the acid chloride in dichloromethane solution (Scheme 5). The isoquinolylmethylamide (24e) was prepared by HBTU coupling of the amine and sodium 3-(4-morpholinyl)propanoate.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Carboxamides.

Substituents X and R of compounds evaluated are given in the tables.

Screening of SMAs

A single screen of a library of 116 novel compounds was carried out for modulation of production of the Th1/Th17 promoting inflammatory cytokines IL-12p40 and IL-6 by bone marrow-derived macrophages (bmMs) in response to the PAMPs, LPS (TLR4), bacterial lipoprotein (BLP, TLR2/6), and CpG motifs (TLR9), to identify SMAs that mimicked the properties of ES-62 (Table 1).4,37,38 Previously, we had successfully tested PC,14 PC-peptides (unpublished), and PC-lipids12,15 in the concentration range 1–10 μg/mL for analysis of effects on cytokine production in vitro, and so a concentration of 5 μg/mL was selected for the current study. Activity at such a concentration would reflect a significant reduction in potency relative to ES-62 (active at 1–2 μg/mL38), which has PC probably accounting for <1% of its mass.39,40 This could possibly be due to the structure of ES-62 and/or its mechanism of interaction with cells, somehow optimizing PC presentation and/or activity.

Table 1. Modulatory Effect of the Library of Small Molecule Analogues on TLR-Dependent Cytokine Productiona.

| (A) phosphonates and phosphates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | X | Y | n | Z | LPS IL-12 | LPS IL-6 | BLP IL-12 | BLP IL-6 | CPG IL-12 | CPG IL-6 |

| 5a | CH2PO3– | 4-Br | 2 | NMe3+ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | |||

| 5b | CH2PO3– | 4-Br | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 5c | CH2PO3– | 4-Me | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | |||||

| 5d | CH2PO3– | 4-NO2 | 2 | NMe3+ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 5e | CH2PO3– | 4-Me | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 6 | OPO3– | 4-BOCNH | 3 | NMe2 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| (B) sulfones | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | X | Y | n | Z | LPS IL-12 | LPS IL-6 | BLP IL-12 | BLP IL-6 | CpG IL-12 | CpG IL-6 |

| 11a | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 2 | Me2N | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| 11b | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 2 | Me2N | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 11c | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 11d | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | |||||

| 11e | CH2SO2 | 3-F | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 11f | CH2SO2 | 3-F | 2 | diam | ||||||

| 11g | CH2SO2 | 3-F | 2 | morph | ↑ | |||||

| 11h | CH2SO2 | 3-F | 2 | pyrrol | ↑ | ↓ | ||||

| 11i | CH2SO2 | 4-F | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 11j | CH2SO2 | 4-F | 2 | morph | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| 11k | CH2SO2 | 4-F | 2 | pyrrol | ↑ | ↓ | ||||

| 11l | CH2SO2 | 4-F | 2 | diam | ↓ | |||||

| 11m | CH2SO2 | 3-F | 2 | S-2-Me-but | ||||||

| 11n | CH2SO2 | 3-F | 2 | R-2-Me-but | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 11o | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 2 | S-2-Me-but | ↓ | |||||

| 11p | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 2 | R-2-Me-but | ||||||

| 12a | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 2 | Me3N+ | ||||||

| 12b | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 2 | Me3N+ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 12c | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 2 | pyrrol Me+ | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 12d | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 2 | pyrrol Me+ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| 16a | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 3 | pyrrol | ||||||

| 16b | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 3 | NMe2 | ↓ | |||||

| 16c | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 3 | morph | ↑ | ↓ | ||||

| 16d | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 3 | pyrrol | ||||||

| 16e | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 3 | NMe2 | ||||||

| 16f | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 3 | morph | ||||||

| 17a | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 3 | morph Me+ | ↑ | |||||

| 17b | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 3 | Me3N+ | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 17c | CH2SO2 | 4-Br | 3 | pyrrol Me+ | ||||||

| 17d | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 3 | pyrrol Me+ | ||||||

| 17e | CH2SO2 | 4-Me | 3 | Me3N+ | ||||||

| 18a | SO2 | H | 2 | diam | ↑ | |||||

| 18b | SO2 | H | 2 | thiomorph | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | |||

| 18c | SO2 | H | 2 | morph | ↑ | ↓ | ||||

| 18d | SO2 | H | 2 | pyrrol | ↑ | ↓ | ||||

| 18e | SO2 | H | 2 | R-2-Me-but | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 18f | SO2 | H | 2 | S-2-Me-but | ||||||

| 18g | SO2 | H | 2 | diam (−Me) | ||||||

| 18h | SO2 | H | 2 | n-Pr | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 18i | SO2 | H | 2 | i-Pr | ↓ | |||||

| 18j | SO2 | H | 2 | 3-OH-n-Pr | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | |||

| 18k | SO2 | H | 2 | t-Bu | ↑ | ↓ | ||||

| 18l | SO2 | H | 2 | 4-Me-pip | ||||||

| (C) sulfonamides

and carboxamides | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | X | Y | n | Z | LPS IL-12 | LPS IL-6 | BLP IL-12 | BLP IL-6 | CpG IL-12 | CpG IL-6 |

| 19a | CH2SO2NH | H | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | |||||

| 19b | CH2SO2NH | H | 2 | pyrrol | ||||||

| 19c | CH2SO2NH | H | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 19e | CH2SO2NH | 4-Br | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 19d | CH2SO2NH | 4-Br | 2 | pyrrol | ↑ | |||||

| 19f | CH2SO2NH | 4-Br | 2 | morph | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 19g | CH2SO2NH | 4-F | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 19h | CH2SO2NH | 4-F | 2 | pyrrol | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||

| 19i | CH2SO2NH | 4-F | 2 | morph | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 19j | CH2SO2NH | 4-Me | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | |||||

| 19k | CH2SO2NH | 4-Me | 2 | pyrrol | ||||||

| 19l | CH2SO2NH | 4-Me | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 19m | CH2SO2NH | 4-NO2 | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | |||||

| 19n | CH2SO2NH | 4-NO2 | 2 | pyrrol | ||||||

| 19o | CH2SO2NH | 4-NO2 | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 19p | CH2SO2NH | 4-Br | 3 | NMe2 | ||||||

| 19q | CH2SO2NH | 4-NO2 | 3 | NMe2 | ↓ | |||||

| 19r | CH2SO2NH | 4-Me | 3 | NMe2 | ||||||

| 19s | CH2SO2NH | 4-F | 3 | NMe2 | ||||||

| 19t | CH2SO2NH | H | 3 | NMe2 | ↑ | |||||

| 19u | CH2SO2NH | 2-naphthyl | 2 | morph | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 19v | CH2SO2NH | 2-naphthyl | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | |||||

| 19w | CH2SO2NH | 2-naphthyl | 2 | NMe2 | ||||||

| 19x | CH2SO2NH | 4-stilbenyl | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | |||||

| 21a | CH2NHSO2 | H | 2 | pyrrol | ||||||

| 21b | CH2NHSO2 | H | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 21c | CH2NHSO2 | H | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | |||||

| 21d | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Br | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 21e | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Br | 2 | pyrrol | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||

| 21f | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Br | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | |||||

| 21g | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Me | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 21h | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Me | 2 | pyrrol | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| 21i | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Me | 2 | NMe2 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 21j | CH2NHSO2 | 4-NO2 | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 21k | CH2NHSO2 | 4-NO2 | 2 | pyrrol | ||||||

| 21l | CH2NHSO2 | 4-NO2 | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| 21m | CH2NHSO2 | 4-F | 2 | morph | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 21n | CH2NHSO2 | 4-F | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| 21o | CH2NHSO2 | 4-F | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | |||||

| 21p | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Me | 2 | diam | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| 21q | CH2NHSO2 | 4-Br | 2 | diam | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| 21r | CH2SO2NH | ‘coumarin’ | 2 | morph | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 21s | CH2SO2NH | ‘coumarin’ | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 21t | CH2SO2NH | ‘coumarin’ | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 23a | NHSO2 | H | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | |||||

| 23b | NHSO2 | H | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 23c | NHSO2 | H | 2 | morph | ||||||

| 23d | NHSO2 | 4-F | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | ↑ | ||||

| 23e | NHSO2 | 4-F | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | |||||

| 23f | NHSO2 | 4-F | 2 | morph | ↓ | ↑ | ||||

| 23g | NHSO2 | 4-F | 2 | diam | ↓ | ↑ | ||||

| 23h | NHSO2 | H | 2 | diam | ↓ | ↑ | ||||

| 24a | CH2CONH | H | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 24b | CH2CONH | H | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| 24c | CH2CONH | H | 2 | morph | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| 24d | CH2CONH | H | 3 | NMe2 | ||||||

| 24e | CH2NHCO | 5-isoquinolyl | 2 | morph | ↓ | |||||

| 25a | CONH | 3-MeO-C6H4 | 2 | NMe2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| 25b | CONH | 3-MeO-C6H4 | 2 | pyrrol | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| 25c | CONH | 3-MeO-C6H4 | 2 | Morph | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| 25d | CONH | 3-MeO-C6H4 | 3 | NMe2 | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | |||

Bone marrow-derived macrophages preincubated for 18 h with 5 μg/mL of compounds were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS, 10 ng/mL BLP, or 0.01 μM CpG in the continued presence of the compounds. After 24 h, supernatants were collected and measured for their IL-12p40 and IL-6 content by ELISA. Arrows down (↓) indicate statistically significant (at least p < 0.05) down-regulation and arrows up (↑) statistically significant up-regulation of the levels of cytokine versus control; blank squares = no significant change. Abbreviations used in structural formulas: ‘coumarin’ = (7-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl; diam = N,N,N-1,1,2-tetramethylethylenediamino2-Me-but = 2-methylbutylamino; 4-Me-pip = 4-methylpiperazinyl; morph = morpholino; 3-OH-n-propyl = 3-hydroxypropylamino; pyrrol = pyrrolidino; stilbenyl = 1-(4-[(E)-2-phenylethyl]benzyl; thiomorph = thiomorpholino.

Many of the compounds were found to demonstrate immunomodulatory activity. However, perhaps unexpectedly, they were selective in terms of the PAMP and/or cytokine responses they affected and, indeed, in some cases cytokine levels were elevated rather than reduced, a result not previously observed with ES-62. Nevertheless, a number of trends are detectable from the cytokine release data.

In general, the tail group structure had no detectable influence on the cytokine release profile although a significant effect of the diamino tail group was observed for 21p and 21q as noted below. Although severely limited by the range of aromatic substituents studied, there was a notable difference between the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine release (4-Br and 4-Me 11a–11d) and the tendency to show a lack of an effect or even an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine release (3-F 11e–11h).

In the sulfone series, compounds with a two-carbon methylene chain (11a–11p and 12a–12d) were generally more effective than comparable compounds with a three-carbon methylene chain (16a–16f and 17a–17e) at inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Shortening the distance between the aromatic ring and the amine essentially increased pro-inflammatory cytokine release (18a–18l), but some reduction of cytokine release was observed, suggesting that there are different targets and mechanisms for these compounds in differently stimulated cells.

The cytokine release signature of many of the sulfonamides was to stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (CSN type 19d–19j, CNS type 21c–21i), and as with the sulfones, there was no evidence for an effect caused by the side chain structure. However there were two subsets of sulfonamides that caused predominant reduction in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines; in the CNS type, compounds with electron withdrawing substituents (F, NO221l–21o) or both CNS and CSN types with large hydrophobic aromatic groups (naphthyl, 19u, ‘coumarinyl’, 21r–21t).

A further special case of reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine release was found for compounds of the CNS type with the dimethylaminoethylamino tail group (21p, 21q) for which some monoamino analogues had the opposite effect (21e, 21f, 21h).

The shortened NSC type of sulfonamide (23a–23h) responded with a decrease in release of IL-12p40 in LPS stimulated cells but an increase in IL-6 release from CpG stimulated cells, again largely independent of tail group structure.

The amides (24a–24c, 25a–25d) almost entirely caused a reduction in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Most strikingly, the phosphate and phosphonates, all of which are zwitterionic, in general caused an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine release, suggesting that a distinctly different mechanism was stimulated by these compounds from that of the nonzwitterionic sulfones, sulfonamides, and amides.

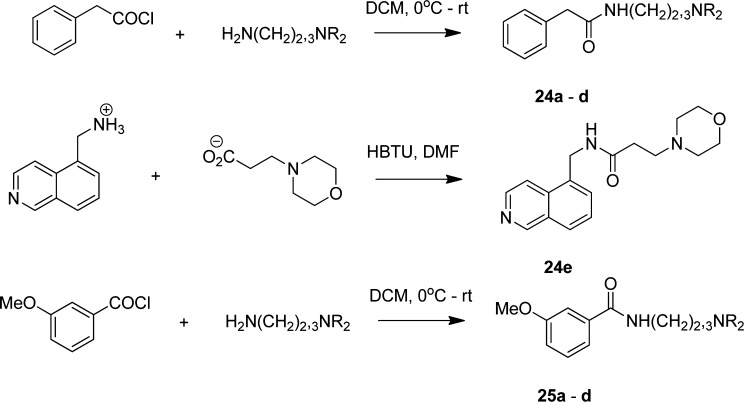

Selection of Compound for in Vivo Evaluation

Of direct relevance to the aims of the project, a number of the compounds reduced production of cytokines important for promoting Th1 and/or Th17 responses, IL-12p40 and/or IL-6, in response to one or more of the TLR ligands. However, some of these did not target either TLR4 (sulfonamide 21o) or TLR2 (sulfonamides 21n, 21o) responses. Likewise, of the carboxamides, 24c only effectively targeted both CpG responses. The most promising compounds were those that showed the broadest response to the PAMPs, the sulfones, 11a and 12b, the sulfonamide 21l, and the carboxamide 24b. 11a (see Figure 3A) and 12b both mimicked ES-62 in targeting IL-12p40 production via each of TLR2, 4, and 9, and this cytokine is pathogenic in CIA41 due to it being a component of both IL-12p70 and IL-23, which promote Th1 and Th17 responses, respectively, and hence a therapeutic target (ustekinumab) in inflammatory autoimmune diseases.42,43 By contrast, sulfonamide 21l and carboxamide 24b did not target LPS- and BLP-mediated IL-12p40 responses, respectively. Sulfone 11a additionally targeted IL-6 production (see also Figure 3B) in response to all three TLRs (although this did not reach statistical significance for TLR2 in all experiments), and this cytokine has also been shown to be pathogenic44 and thus a therapeutic target (tocilizumab) in RA.45 Although sulfone 12b could suppress CpG-mediated IL-6 responses, it was less effective at inhibiting such TLR2- or TLR4-coupled responses (decreases not reaching statistical significance), which have been shown to be important in the development of inflammatory Th17 responses, including those in arthritis.46−48 Moreover, as observed with ES-62,40,49 (11a (Figure 3C), but not 21l (results not shown), was able to inhibit TLR-mediated p65 NF-κB activation in response to all three PAMPs.

Figure 3.

11a-related changes in macrophage cytokine production and signaling of p65 NFκB in response to LPS, BLP, and CpG. BmMs were preincubated with 11a at 5 μg/mL for 18 h prior to stimulation with 100 ng/mL LPS, 10 ng/mL BLP, or 0.01 μM CpG for 24 h and analysis of levels of IL-12p40 (A) and IL-6 (B) performed by ELISA. (C) Stimulation with PAMPs as above for LPS and BLP, and 1 μM CpG, but for 1 h and the level of p65 activation in duplicate samples measured by TransAM. For statistical analysis for (A) and (B), *p < 0.05.

Thus, as both IL-6 and IL-12p40 (via IL-23) promote the differentiation and maintenance of Th17 responses, it was considered that 11a was most likely to mimic the protective effects of ES-62 in CIA by suppressing production of IL-17,9 a cytokine that is pathogenic in RA and an emerging therapeutic target (for example via the humanized monoclonal antibody LY2439821 and the human monoclonal antibody AIN457; reviews refs (42,50−52)). Limited analysis of potency revealed that 11a was still able to induce a statistically significant reduction of LPS-stimulated production of IL-6 by macrophages when the concentration was reduced to 1 μg/mL, but significant effects were not consistently observed at 0.2 μg/mL (data not shown). Like ES-62, 11a showed no evidence of toxicity under conditions mimicking the macrophage screen of cytokine production as determined using the cell viability indicator, 7-actinomycin D (7-AAD) (Figure 4). Indeed, the SMA showed some evidence of protecting against the loss of cell viability associated with exposure to LPS. 11a was thus considered suitable for testing in vivo.

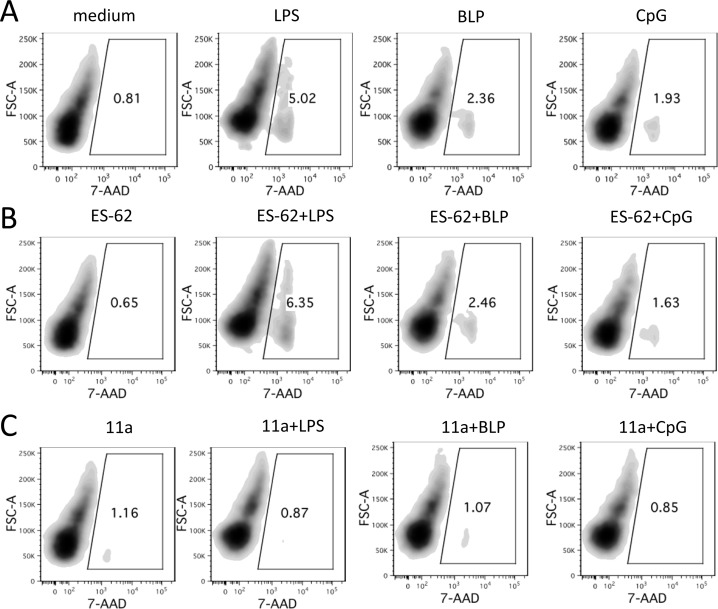

Figure 4.

Lack of toxic effect of 11a on macrophages. BmMs in ultralow binding tissue culture plates were rested in RPMI complete medium for 24 h before culturing with fresh medium or medium containing 11a (5 μg/mL) or ES-62 (2 μg/mL). After 18 h, the macrophages were stimulated with medium containing 100 ng/mL LPS or 10 ng/mL BLP or 0.01 μM CpG for an additional 24 h before staining with 7-AAD to assess their viability. The samples were analyzed by flow cytometry, and the data are presented as density plots with frequency of 7-AAD positive (dead) cells indicated in the gates. The results shown are from a single experiment representative of two independent experiments.

In Vivo Evaluation: 11a Protects against Collagen-Induced Arthritis

11a, at a low dose of ∼50 μg/kg per injection, was tested in the CIA model and it was found that, as with ES-62, it effectively reduced development of arthritis in treated mice. This was reflected in each of disease scores (Figure 5A), hind paw width (Figure 5B), disease incidence (Figure 5C), and percentage of mice with high disease scores (Figure 5D). Moreover, whereas mice with CIA exhibited a significant increase in DLN cell number over the control group not exposed to collagen, this was significantly reduced by treatment with 11a (Figure 5E) and to a level not significantly different from the control naive group. This result was mirrored by analysis of defined T cell populations, namely CD4+ T cells (Figure 5F), CD8+ T cells (Figure 5G), and γδ T cells (Figure 5H), where 11a-treated mice showed reduced levels of cells relative to mice with CIA and/or levels not significantly different to the control group of naive mice not exposed to collagen. Previously we had found that CD4+ and γδ T cells from ES-62-treated mice were similarly reduced, although statistical significance had not been reached.9

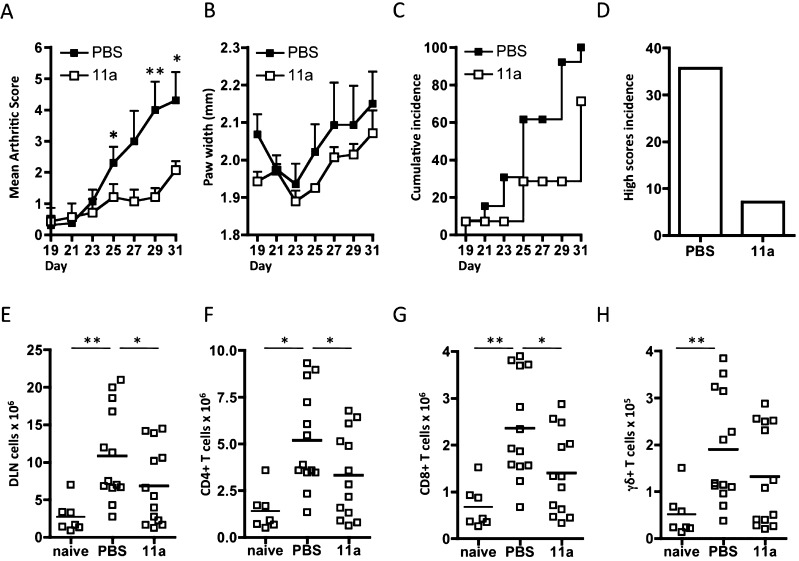

Figure 5.

11a protects against CIA. Disease is shown by each of mean arthritis score ((A) PBS, n = 13; 11a, n = 13, data pooled from two independent experiments), hind paw width ((B) n = 7, data from a single experiment), and incidence (C,D) indicated by the % of mice developing a severity score ≥2 ((C) cumulative incidence) or ≥4 ((D) high score incidence). Results are expressed as mean scores ± SEM for PBS or 11a-treatment groups of mice exposed to collagen. The numbers of each of total (E), CD4+ (F), CD8+ (G), and γδ (H) T cells in DLN of individual mice from the naïve (n = 7), PBS-treated (n = 13) and 11a-treated (n = 13) groups are shown. For statistical analysis, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

11a Protection against CIA Correlates with Suppression of IFNγ and IL-17 Responses

Our previous work with ES-62 showed that it suppressed both IFNγ and IL-17 responses7,9 and hence we investigated whether this was also the case for 11a. Indeed, similarly to ES-62, we found 11a to target IFNγ (Figure 6A) and IL-17 (Figure 6B) responses in DLN cells stimulated with PMA/ionomycin ex vivo. First, whereas mice with CIA displayed significantly higher numbers of DLN, CD8+ T, and CD4+ T cells producing IFNγ in response to PMA/ionomycin-stimulation than naïve mice, this was not true of the 11a-treated mice exposed to collagen. Moreover, the numbers of IFNγ-expressing cells in the DLN and CD8+ T cell populations were significantly reduced in the 11a group relative to the PBS-CIA group (Figure 6A). However, no significant difference in IFNγ-producing γδ T cells was found between the mice exposed to collagen given 11a or not (results not shown). With respect to IL-17, the effects observed were not as striking although it was still possible to see clear evidence that this pro-inflammatory cytokine was also being targeted. Thus, for example, the numbers of DLN, CD4+, and γδ T cells were significantly higher in PBS, but not 11a, treated mice undergoing CIA than in mice not exposed to collagen (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

11a suppresses IFNγ and IL-17 responses in CIA. Exemplar plots of gating strategy of intracellular IFNγ (A) and IL-17 (B) expression by DLN cells from representative individual PBS-treated mice with CIA show forward scatter (FSC) or CD4, CD8, and γδ expression on the y-axis versus cytokine expression on the x-axis as indicated. The number of (A) IFNγ-expressing total DLN cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T cells and (B) IL-17-expressing total DLN cells, CD4+ T cells, and γδ T cells following stimulation with PMA/ionomycin from individual mice are shown (naïve, n = 7; PBS, n = 13; 11a, n = 13). For statistical analysis, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Unlike in our earlier study with ES-62,911a did not induce a statistically significant reduction in the serum levels of IL-17 in these mice (Figure 7A). However, in our previous study,9 it was shown that pre-exposure to ES-62 inhibited the capacity of dendritic cells (bmDCs) to respond to LPS by secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and two cytokines, IL-6 and IL-23, associated with polarization and maintenance of Th17 cells, respectively, and when these experiments were repeated with the bmDCs pre-exposed to 11a, production of all three cytokines was significantly reduced (Figure 7B). As with ES-62,4 this did not reflect downregulation of TLR4 expression or reduction in bmDC viability (data not shown). Furthermore, consistent with the ability of 11a to inhibit production of the two Th17-promoting cytokines, 11a-treated DCs demonstrate a reduced ability to drive naïve antigen (OVA)-specific Th cells toward a Th17 phenotype, as evidenced by suppression of OVA-specific IL-17 production in such bmDC-CD4+ T cell cocultures (Figure 7C,D). Again, this is consistent with what was previously observed with ES-62.9

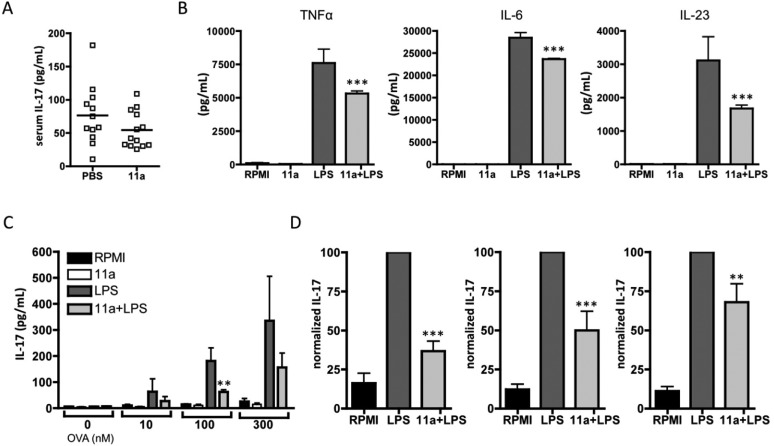

Figure 7.

11a inhibits Th17 polarization. (A) Serum IL-17 levels are plotted as mean values of triplicate IL-17 analyses from individual mice (PBS, n = 12; 11a, n = 13). (B) BmDCs from C57BL/6 mice were preincubated with or without (11a) (5 μg/mL) for 2 h prior to stimulation with LPS for 24 h, and TNFα, IL-6, and IL-23 levels were then analyzed. Data are the mean values (of triplicate samples) ± SEM pooled from 4 independent experiments. (C) BmDCs from BALB/c mice preincubated with or without 11a (5 μg/mL) were pulsed with the indicated concentration of OVA peptide and cocultured with naive OVA-specific CD4+ T cells (DO.11.10/BALB/c) for 3 days before measuring IL-17 release. Data are the mean values ± SD of duplicate samples pooled from two independent experiments (n = 4). (D) Pooled normalized data from four independent experiments analyzing the effect of 11a on IL-17 release from bmDC (C57BL/6)-OVA-specific CD4+T cell (OT-II/C57BL/6) cocultures. Data are presented as the means of the mean percentage maximum (LPS) response ± SEM where data were normalized to the LPS response at 10 nM (left), 100 nM (middle), and 300 nM (right) OVA, respectively. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

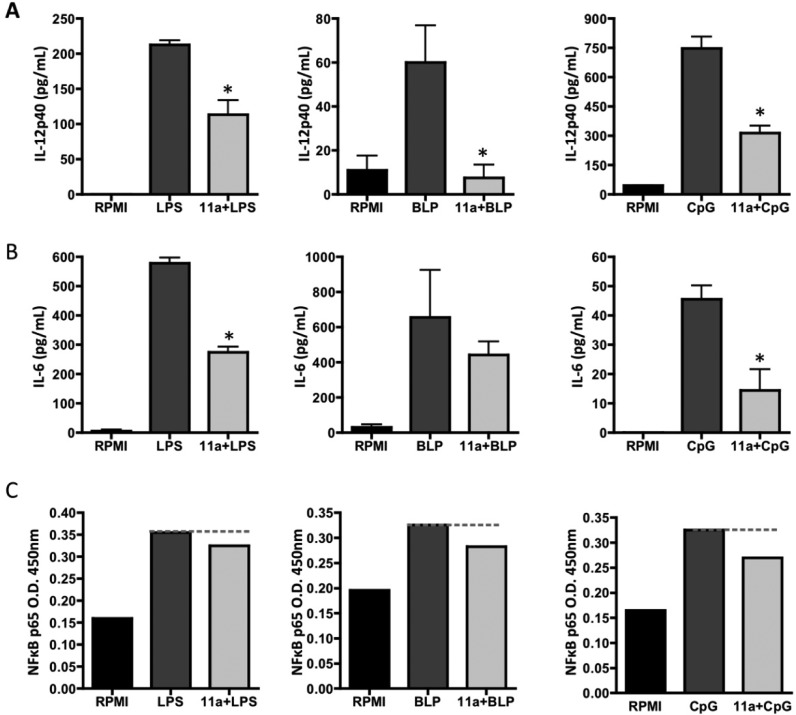

11a Is Able to Cause Downregulation of the TLR Signaling Adaptor Myeloid Differentiation Primary Response Gene 88 (MyD88)

Previous work published by our group has shown that ES-62’s mechanism of action involves downregulation of the key TLR/IL-1R signaling adaptor MyD88 in Th17 cells9 and mast cells.53 This is also true of macrophages (our unpublished results), the cell type used for our primary screen, and so we next investigated whether 11a was also able to cause downregulation of MyD88 in these cells. As shown in Figure 8A,B, the SMA does indeed cause significant downregulation of the signaling adaptor in these cells. Figure 8A–C also shows that, as expected, LPS causes an increase in MyD88 expression within the cells, but as demonstrated in Figure 8C, this is prevented by 11a. A simple schematic of the proposed mechanism of action of 11a is shown in Figure 8D and described in detail in the figure legend.

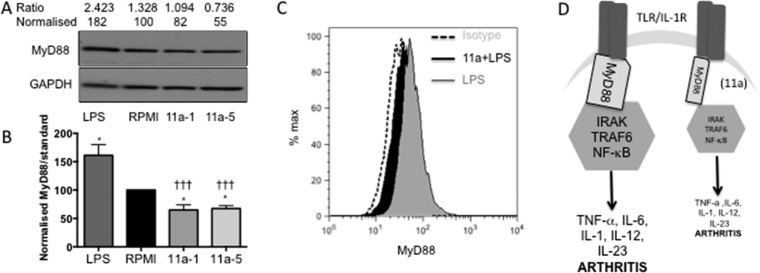

Figure 8.

11a downregulates MyD88 expression in macrophages. (A) BmMs treated with medium (RPMI), 11a at 1 and 5 μg/mL (11a-1 or 11a-5), or LPS (100 ng/mL) for 20 h were analyzed by Western blotting for expression of MyD88 and loading control GAPDH. Levels of expression were determined by densitometry using Image-J software and expressed as the ratio of MyD88:GAPDH and normalized to the RPMI value. (B) Data from six analyses revealed that while LPS significantly increased MyD88 expression (*p < 0.05), both 11a-1 and 11a-5 reduced it (*p < 0.05) relative to the RPMI control. In addition, the level of MyD88 in cells treated with either 11a-1 or 11a-5 was significantly different (†††p < 0.001) to that in those exposed to LPS. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of MyD88 expression in permeabilised bmMs relative to isotype control (20,000 bmMs/treatment group). BmMs were treated with RPMI or 11a (at 5 μg/mL) for 2 h prior to exposure to LPS (100 ng/mL) for a further 18 h, and consistent with the Western blot data, LPS upregulated levels of MyD88 (127% relative to MFI of RPMI-treated bmMs). Moreover, bmMs pretreated with 11a exhibited lower levels of MyD88 expression (MFI for 11a + LPS is 95.7% of the level of the RPMI value: the RPMI trace is not shown due to its overlap with that of 11a + LPS) than cells treated with LPS alone. (D) Simple schematic of model of action of 11a. 11a downregulates MyD88 expression and hence induces a partial uncoupling of TLR/IL-1R from NF-κB activation and consequent pro-inflammatory cytokine production that both initiates pathogenic IL-17-mediated inflammation and perpetuates chronic vascular permeability, inflammation, and pathology in the joints.54,55 Thus 11a-mediated downregulation of MyD88 impacting at one or more of these sites provides a molecular mechanism for the protection afforded in CIA.

Discussion and Conclusions

The increasing awareness of the therapeutic potential of parasitic worms has resulted in a search to identify defined molecules that possess immunomodulatory properties and recently details of a number of these have appeared.11 Although some of the molecules characterized to date are carbohydrate56 or lipid57 in nature, the majority are proteins, and hence there is the potential problem of their immunogenicity possibly interfering with activity. ES-62, which is among the best characterized of helminth-derived immunomodulators,58 is active in mouse models of both allergic and autoimmune diseases58 and has been suggested as being the helminth-derived molecule for which there is most potential in testing in humans for treatment of such disorders.59 Furthermore, PC-containing molecules circulate in the bloodstream of humans infected with filarial nematodes for decades without inducing any known adverse effects on general health or compromising the capacity to fight infection, therefore suggesting that ES-62 might be safer than current immunosuppressive drugs, including glucocorticoids or biologics, used to treat human inflammatory diseases. However, as a large protein, ES-62 is subject to the problem of immunogenicity referred to above and hence in reality is not suitable for use as a drug. Nevertheless, our data obtained to date indicated that PC is the key anti-inflammatory moiety of ES-62,5,8,10,11 and this was confirmed in the present study as when conjugated to BSA, it was found to mimic the suppressive effects of ES-62 on IL-17 and IFNγ responses. Hence we decided to pursue a novel strategy of drug development: designing synthetic small drug-like compounds based around PC.

The SMA library was initially subjected to a simple in vitro screen that involved determining the effect of the compounds on PAMP-induced macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine responses, in particular focusing on those mediators that might contribute to Th1/Th17 responses, which are known targets of ES-62 in CIA.9 The results of this screen were surprising, in that although a number of the SMAs targeted macrophage responses, the effects were more selective than those recorded previously with ES-62, in the sense that not all PAMP-induced cytokine responses were inhibited. Although unexpected, these may actually be potentially important observations, raising the possibility of generating drugs more specific than ES-62 with respect to anti-inflammatory activity. Another unexpected finding was that rather than inhibiting the cytokine responses, a number of the SMAs increased certain responses. Although we have previously shown variation in inhibitory effects of small PC-containing molecules,12 we did not observe any stimulatory effects. The reasons underlying such SMA-mediated promotion of TLR-driven cytokine responses, which potentially could reflect adjuvant-like applications for these compounds similar to those based on classical pro-inflammatory TLR ligands,20 have not been investigated at this stage. However, the data underline the point that structurally closely related compounds may vary with respect to immunomodulatory activity and hence require careful analysis at the individual level.

On the basis of previous in vitro analysis of the effects of ES-62 on macrophages,4,5 allied to its protective effects in CIA,7−9 sulfone 11a was selected from the in vitro screen as a molecule showing properties that might suggest activity against CIA similar to ES-62. We employed the dosing schedule used successfully with ES-62, which was based on the premise that exposing the mice to the parasite product both prior to and at the time of immunization will maximize the potential for modulating initiation of pathogenic immune responses while re-exposure at d21 in the antigen challenge phase will target ongoing and/or memory responses and therefore reflect a more therapeutic regime. This revealed that 11a not only demonstrated efficacy against disease development that mirrored that of the parent molecule but in inhibiting IFNγ and to a lesser extent, IL-17 production, showed evidence of the same immunological mechanism of action. Our aim in this study was simply proof of concept that an SMA could afford protection using a regimen previously shown to be successful with ES-62, and thus it is possible that the molecule can be shown to be even more effective with optimization of dosage regimen. Further support for targeting of IL-17 responses is shown by 11a mirroring ES-62 in preventing secretion by dendritic cells, of cytokines involved in polarization and maintenance of Th17 cells, and inhibiting the subsequent ability of such DCs to prime Th17 responses. Moreover, 11a is able to cause downregulation of the key signaling adaptor MyD88 in macrophages. This is consistent with its effects on NF-κB activation and explains its ability to mimic a primary mechanism of action of ES-62 in suppressing TLR-mediated cytokine production.9,53 In addition, such targeting of MyD88 provides a molecular rationale (Figure 8D) for the protection against CIA afforded by 11a as TLR/MyD88-dependent signaling has been proposed to be pathogenic in both CIA and RA. Moreover, the recent use of MyD88-deficient mice has shown this signaling element to be crucial to development of IL-17-driven arthritis, both in terms of initiation of pathogenic IL-17 responses and also the severity of joint inflammation and pathology.17−20,54,55

11a is of course too small to be immunogenic, but it also possesses another feature that increases its candidature as a more effective version of ES-62 for therapeutic purposes. It contains a tertiary dimethylamino group in contrast to the quaternary trimethylammonium choline component of PC; previously we have shown that unlike choline, its dimethylamino analogue does not compete for binding to the myeloma protein TEPC 15, an antibody which recognizes PC.60 This suggests that 11a will not bind to endogenous anti-PC antibodies that are found in humans and which could conceivably interfere with activity of PC-containing SMAs. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that natural anti-PC antibodies by an as yet unknown mechanism may in themselves be anti-inflammatory, protecting humans from diseases such as atherosclerosis,61 and so this represents another reason for designing drugs that avoid interacting with them. In this way, possessing the tertiary amine rather than quaternary ammonium salt choline may result in a safer as well as a more effective drug.

Finally, although based on a combination of epidemiological evidence and model studies there has been much enthusiasm for the idea that parasitic worms may represent a starting point for novel drug design for diseases associated with aberrant inflammation, relevant studies are at an early stage and to date no actual drugs have been produced. However, the work presented in this paper serves as a strong proof of concept that novel small molecules can be active against severe and complex diseases in vivo. Moreover, the compounds described here benefit from ease of synthesis and active compounds such as 11a can be readily subjected to further chemical manipulation to optimize properties as required. In general, this study suggests that there is great medicinal chemical potential to be found in synthetic libraries based around active moieties of helminth-derived molecules.

Experimental Section

Preparation of SMAs

For assay, all compounds tested were of greater than 95% purity. Compounds were reconstituted at 100 mg/mL in cell culture-tested DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, UK), diluted in RPMI medium to 1 mg/mL, and stored in microcentrifuge tubes at −20 °C. Compounds were sterilized using a Millex-GP (0.22 μm) (Millipore, UK) filter unit prior to use in culture. All reagents and plastics used were sterile and pyrogen free.

General Methods for Synthesis

1H and 13C NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker DPX-400 MHz spectrometer with chemical shifts given in ppm (δ values) relative to proton and carbon traces in solvent. Coupling constants are reported in Hz. IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer 1 FT-IR spectrometer. Elemental analysis was carried out on a Perkin-Elmer 2400, analyzer series 2. Mass spectra were obtained on a Jeol JMS AX505. Anhydrous solvents were obtained from a Puresolv purification system, from Innovative Technologies, or purchased as such from Aldrich. Melting points were recorded on a Reichert hot-stage microscope and are uncorrected. Chromatography was carried out using 200–400 mesh silica gels or using reverse-phase HPLC on a Waters system using a C18 Luna column.

Declaration of Purity

All final compounds were equal or more than 95% pure by HPLC and 1H NMR.

Diethyl 4-Bromobenzylphosphonate62 (3a)

1-Bromo-4-(bromomethyl)benzene (3.10 g, 12.5 mmol) was suspended in triethylphosphite (2.4 mL, 13.7 mmol, 1.1 equiv), and the mixture was heated under reflux under N2 for 6 h. Excess triethylphosphite was removed under reduced pressure to give the required product as a yellow oil (3.50 g, 91%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.51 (2H, dd, J = 8.4 Hz and J = 0.9 Hz), 7.25 (2H, dd, J = 8.4 and 2.5 Hz), 3.96–3.91 (4H, m), 3.25 (2H, d, J = 21.6 Hz), 1.19 (6H, t, J = 7.1 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 131.9, 131.8, 131.0, 119.7, 61.4, 32.2, 16.2. IR (NaCl): 3447, 2982, 1646, 1513, 1488, 1392, 1249, 1093, 1057, 963, 853, 766 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C11H16O379BrP, 306.0020; found, 306.0020.

Diethyl 4-Methylbenzylphosphonate62 (3b)

1-(Bromomethyl)-4-methylbenzene (2.60 g, 14.0 mmol) was suspended in triethylphosphite (2.9 mL, 16.7 mmol), and the mixture was heated under reflux under N2 for 20 h. Excess triethylphosphite was removed under reduced pressure to give the required product as a colorless oil (3.20 g, 94%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.17 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.12 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 3.96–3.88 (4H, m), 3.17 (2H, d, J = 20 Hz), 2.27 (3H, s), 1.18 (6H, t, J = 7.1 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 135.4, 129.5, 129.1, 128.9, 61.2, 32.4, 20.6, 16.1. IR (NaCl): 3439, 2982, 2901, 2902, 1651, 1516, 1443, 1391, 1251, 1163, 1058, 963, 841, 783 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C12H19O3P, 242.1072; found, 242.1069.

Diethyl 4-Nitrobenzylphosphonate63 (3c)

1-(Bromomethyl)-4-nitrobenzene (2.44 g, 11.3 mmol) was suspended in triethylphosphite (5.0 mL, 28.79 mmol), and the mixture was heated under reflux under N2 for 20 h. Excess triethylphosphite was removed under reduced pressure to give the required product as a brown oil (6.60 g, 89%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 8.19 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.58 (2H, dd, J = 8.7 Hz and J = 2.3 Hz), 4.07 (4H, q, J = 7.1 Hz), 3.48 (2H, d, J = 22.4 Hz), 1.19 (6H, t, J = 7.1 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 146.2, 141.0, 130.9, 123.2, 62.6, 32.9, 16.2. IR (NaCl): 3466, 2983, 1600, 1520, 1347, 1248, 1027, 966, 860, 796, 694 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C11H16NO5P, 273.0766; found, 273.0763.

4-Bromobenzylphosphonic Acid64 (4a)

Diethyl 4-bromobenzylphosphonate (3.74 g, 12.20 mmol) was suspended in 12 M HCl (30 mL), and the mixture was heated under reflux for 48 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to give the required product as an off-white solid (2.20 g, 72%), mp 167–175 °C [slow decomposition]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.71 (2H, br, s, OH), 7.47 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.20 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 2.97 (2H, d, J = 20.0 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 35.4, 34.1, 119.1, 130.8, 131.9, 133.8. IR (KBr): 2670, 2258, 1911, 1557, 1491, 1409, 1260, 1240, 1105, 999, 823, 703 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C7H879,81BrO3P, 249.9394/251.9375; found, 249.9389/251.9375.

4-Methylbenzylphosphonic Acid65 (4b)

Diethyl 4-methylbenzylphosphonate (3.48 g, 14.40 mmol) was suspended in 12 M HCl (30 mL), and the mixture was heated under reflux for 56 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to give the required product as a white solid (1.99 g, 74%), mp 186–187 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.58 (2H, br, s, OH), 7.14 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.08 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 2.92 (2H, d, J = 21.2 Hz), 2.26 (3H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 135.2, 131.5, 129.95–129.94, 35.9, 21.4. IR (KBr): 2921, 2324, 1514, 1455, 1269, 1235, 1196, 1107, 996, 969, 946, 814, 740 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C8H11O3P, 186.0445; found, 186.0446.

4-Nitrobenzylphosphonic Acid66 (4c)

Diethyl 4-nitrobenzylphosphonate (2.91 g, 10.60 mmol) was suspended in 12 M HCl (90 mL), and the mixture was heated under reflux for 18 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to give the required product as a brown solid (1.82 g, 93%), mp 208–214 °C [lit. mp 228–229 °C]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.45 (2H, br, s, 2H, OH), 7.2–8.2 (4H, m), 2.98 (2H, d, J = 20.0 Hz).

2-{[(4-Bromobenzyl)(hydroxy)phosphoryl]oxy}-N,N,N-trimethylethanaminium Iodide (5a)

4-Bromobenzylphosphonic acid (0.700 g, 2.80 mmol) was suspended in thionyl chloride (5 mL), and the mixture was heated under reflux for 30 h under nitrogen. When the reaction mixture cooledd to room temperature, excess thionyl chloride was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in chloroform (20 mL, dry). This solution was then transferred via syringe to a flame-dried, three-necked round-bottomed flask under nitrogen. This solution was then cooled to 0 °C, followed by the addition of pyridine (2 mL, dry) and the portionwise addition of choline iodide (0.82 g, 3.55 mmol). Stirring was continued for a further 3 days. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was suspended in acetonitrile (2 mL). HPLC purification gave the required product as a colorless oil (0.071 g, 56%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.47 (2H, d, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.24 (2H, d, J = 7.5 Hz), 4.18 (2H, br, s), 3.54 (2H, m), 3.04 (9H, s), 2.99 (2H, d, J = 20 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 139.7, 137.5, 136.4, 124.7, 70.9, 63.6, 58.7, 39.7, 38.4. IR (NaCl): 3383, 3030, 2957, 2913, 1896, 1767, 1686, 1485, 1337, 1241, 1202, 1163, 1093, 1012, 970, 830, 713 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C12H20NO3P79,81Br, 336.0364/338.0345; found, 336.0362/338.0339.

2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl Hydrogen 4-Bromobenzylphosphonate Trifluoroacetate (5b)

4-Bromobenzylphosphonic acid (0.455 g, 1.81 mmol) was suspended in thionyl chloride (5 mL), and the mixture was heated under reflux for 20 h. When the reaction mixture cooled to room temperature, excess thionyl chloride was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in DCM (10 mL, dry). To this solution was added, at 0 °C, pyridine (400 μL, 4.9 mmol, dry) and dimethylethanolamine (122 μL, 2.2 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h before the addition of water (1 mL). Stirring was continued for a further 20 h, after which time the solvent was removed under reduced pressure until ∼1 mL of crude solution was left. The crude mixture was then purified by reverse phase HPLC to give the required product as a colorless oil (295 mg, 37%) as a TFA salt. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.50 (2H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.26 (2H, dd, J = 2.3 Hz and J = 8.4 Hz), 4.15–4.10 (2H, m), 3.29 (2H, t), 3.15 (2H, d, J = 21.4 Hz), 3.76 (6H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 133.1, 131.8, 128.8, 119.4, 58.7, 56.7, 42.6, 32.1, 31.6. IR (NaCl): 3419, 3038, 2912, 2714, 2521, 1772, 1678, 1572, 1488, 1407, 1242, 1204, 1052, 1020, 836, 795, 720 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C12H20NO3P79,81Br, 336.0364/338.0345; found, 336.0362/338.0339.

2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl Hydrogen 4-Methylbenzylphosphonate Trifluoroacetate (5c)

4-Methylbenzylphosphonic acid (0.39 g, 2.10 mmol) was suspended in thionyl chloride (5 mL), and the mixture was heated under reflux for 20 h. When the reaction mixture cold to room temperature, excess thionyl chloride was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in chloroform (20 mL, dry). To this solution was added, at 0 °C, pyridine (600 μL, 7.3 mmol, dry) and dimethylethanolamine (300 μL, 2.98 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h before the addition of water (1 mL). Stirring was continued for a further 20 h, after which time the solvent was removed under reduced pressure until around 2 mL of crude solution was left. The crude mixture was then purified by reverse phase HPLC to give the required product as colorless oil (295 mg, 37%) as a TFA salt. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.17 (2H, dd, J = 2.1 Hz and J = 8.0 Hz), 7.10 (2H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 4.09–4.05 (2H, m), 3.24 (2H, t), 3.05 (2H, d, J = 21.2 Hz), 2.72 (6H, s), 2.26 (3H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 135.0, 130.6, 129.5, 128.6, 58.7, 56.9, 42.5, 33.7, 32.3, 20.6. IR (NaCl): 3418, 3030, 2964, 2921, 2714, 2528, 1766, 1682, 1515, 1472, 1416, 1321, 1203, 1088, 1020, 993, 832, 799, 720 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C12H21O3NP, 258.1259; found, 258.1258.

2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl Hydrogen 4-Nitrobenzylphosphonate Trifluoroacetate (5d)

4-Nitrobenzylphosphonic acid (0.345 g, 1.59 mmol) was suspended in thionyl chloride (5 mL), and the mixture was heated under reflux for 20 h. When the reaction mixture cold to room temperature, excess thionyl chloride was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in DCM (10 mL, dry). Pyridine (350 μL, 4.3 mmol, dry) and dimethylethanolamine (192 μL, 1.91 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h before the addition of water (1 mL). Stirring was continued for a further 20 h, after which time the solvent was removed under reduced pressure until ∼1 mL crude solution was left. The crude mixture was then purified by reverse phase HPLC to give the required product as colorless oil (200 mg, 31%) as a TFA salt. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 8.18 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.56 (2H, dd, J = 2.3 Hz and J = 8.8 Hz), 4.14–4.09 (2H, m), 3.31 (2H, d, J = 21.2 Hz), 3.25–3.23 (2H, m), 2.75 (6H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 146.0, 142.7, 130.9, 123.1, 58.7, 56.9, 42.5, 34.3, 33.8. IR (KBr): 1767, 1680, 1514, 1472, 1414, 1320, 1202, 1087, 1020, 992, 832, 800, 721 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C11H18O5N2P, 289.0953; found, 289.0957.

3-(Dimethylamino)propyl Hydrogen 4-Methylbenzylphosphonate Trifluoroacetate (5e)

4-Methylbenzylphosphonic acid (0.25 g, 1.34 mmol), was suspended in thionyl chloride (7 mL), and the mixture was heated to reflux for 20 h. When the reaction mixture cold to room temperature, excess thionyl chloride was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in chloroform (20 mL, dry). To this solution was added, at 0 °C, pyridine (295 μL, 3.6 mmol, dry) and 3-(dimethylamino)-1-propanol (190 μL, 1.60 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h before the addition of water (1 mL). Stirring was continued for a further 20 h, after which time the solvent was removed under reduced pressure until around 2 mL of crude solution were left. The crude mixture was then purified by reverse phase HPLC to give the required product as a colorless oil (0.191 g, 37%) as a TFA salt. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.16 (2H, dd, J = 8.0 Hz and 2.0 Hz), 7.10 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 3.90 (2H, m), 3.03 (2H, d, J = 21.2 Hz), 3.01–2.98 (2H, m), 2.71 (6H, s), 2.27 (3H, s), 1.90–1.84 (2H, m). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 135.1, 130.5, 129.6, 128.6, 61.2, 53.8, 42.1, 33.8, 32.5, 25.1, 20.6. IR (NaCl): 3419, 3021, 2961, 2906, 2719, 2637, 1682, 1515, 1470, 1410, 1202, 1133, 1049, 971, 830, 719 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C13H23NO3P, 272.1416; found, 272.1418.

tert-Butyl 4-Hydroxyphenylcarbamate67 (6a)

4-Aminophenol (0.67 g, 6.14 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (15 mL, dry) under nitrogen and the mixture cooled to 0 °C before the addition of BOC anhydride (1.40 g, 6.45 mmol). The mixture was gradually allowed to warm to room temperature, and stirring was continued for 20 h at room temperature. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dried in a drying pistol 60 °C for 2 h, to give the required product as an off-white solid (1.19 g, 93%), mp 146–148 °C [lit. mp 146 °C]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 8.99 (1H, s, NH), 8.94 (1H, br, s, OH), 7.21 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.64 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 1.40 (9H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 152.9, 152.5, 130.9, 120.0, 114.9, 78.4, 28.2. IR (KBr): 3361, 2975, 2936, 2876, 1696, 1610, 1531, 1436, 1370, 1231, 1165, 1058, 1029, 1014, 829, 803 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C11H15NNaO3, 232.0950; found, (M + Na): 232.0951.

tert-Butyl 4-{[[3-(Dimethylamino)propoxy](hydroxy)phosphoryl]oxy} Phenylcarbamate Trifluoroacetate (6b)

tert-Butyl 4-hydroxyphenylcarbamate (0.42 g, 2.00 mmol) was dissolved in chloroform (30 mL, dry) to which potassium carbonate (0.31 g, 2.20 mmol) and phosphorus oxychloride (0. 240 mL, 2.57 mmol) were added at 0 °C, under nitrogen. After 2 h, pyridine (2 mL, dry) and dimethylaminopropanol 0.30 mL, 2.54 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min then allowed to warm to room temperature. Stirring was continued for 72 h. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue by HPLC purification gave the required product as white solid (0.012 g, 16%), mp 144–146 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.25 (1H, br, s, NH), 7.38 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.06 (2H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 1.90 (2H, t), 1.46 (9H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 153.7, 147.3, 136.4, 121.1, 120.0, 79.8, 62.7, 54.9, 42.7, 29.0, 26.7. IR (KBr): 3414, 2981, 2929, 1700, 1605, 1513, 1410, 1393, 1311, 1214, 1161, 1054, 967, 841, 773, 701 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C16H27N2O6P, 375.1685; found, 375.1684.

2-[(4-Bromobenzyl)sulfanyl]ethanol (7a)

1-Bromo-4-(bromomethyl)benzene (10.00 g, 40.00 mmol), 2-mercaptoethanol (3.13 g, 40.00 mmol), and K2CO3 (5.53 g, 40.00 mmol, anhydrous) were added to DCM (50 mL, dry) at room temperature with stirring. Stirring was continued for 48 h, after which time water was added and then the reaction mixture was extracted with DCM. The organic layer was collected, dried (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure to give the required product as a pale-yellow oil (11.00 g, 99%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.46 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.22 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 3.71 (2H, s), 3.70 (2H, t, J = Hz), 2.65 (2H, t, J = 8.0 Hz), 1.93 (1H, br, s, OH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 137.4, 131.9, 130.8, 121.3, 60.6, 35.4, 34.6. IR (thin film): 3390 (br), 2919, 1901, 1663, 1589, 1486, 1402, 1289, 1198, 1096, 1069, 1011, 881, 821 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C9H1179/81BrOS, 245.9714/247.9693; found, 245.9712/245.9692.

2-[(4-Methylbenzyl)sulfanyl]ethanol68 (7b)

1-(Bromomethyl)-4-methylbenzene (10.00 g, 54.03 mmol), 2-mercaptoethanol (4.22 g, 54.03 mmol), and K2CO3 (7.47 g, 54.03 mmol, anhydrous) were added to DCM (50 mL, dry) at room temperature with stirring. The stirring was continued for 48 h. Water was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted with DCM. The organic layer was collected, dried (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure to give the required product as a pale-yellow oil (9.60 g, 98%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.23 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.14 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.79 (1H, t, J = 14.3 Hz, OH), 3.72 (2H,s), 3.57 (2H, m), 2.52 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 2.30 (3H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 135.7, 135.6, 128.8, 128.7, 60.6, 35.0, 33.3, 20.6. IR (KBr): 1664, 1513, 1422, 1386, 1098, 1068, 1020, 878, 817, 726 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C10H14OS, 182.07654; found, 182.0764.

2-[(4-Bromobenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanol (8a)

2-[(4-Bromobenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanol (11.00 g, 44.7 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (50 mL, dry) to which m-CPBA (21.10 g, 122.3 mmol) was added at room temperature with stirring. The reaction was slightly exothermic. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Then 15 min after the addition of m-CPBA, a white solid material precipitated. NaHCO3 (saturated) was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted. The organic layer was extracted with brine and collected, dried (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was applied to a gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1/1, RF = 0.1 to give the pure material as white crystals (4.47 g, 36%) after recrystallization from ethyl acetate/n-hexane, mp 97–99 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.61 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.37 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 5.21 (1H, br s, OH), 4.48 (2H, s), 3.83 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 3.18(2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 133.2, 131.3, 128.1, 121.8, 58.8, 54.9, 53.9. IR (KBr): 3480 (br), 2991, 2928, 1490, 1408, 1388, 1291, 1262, 1235, 1115 (s), 1064, 1014, 848, 808, 705, 523 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C9H1179/81BrO3S, 277.9612/279.9592; found, 277.9614/279.9586.

2-[(4-Methylbenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanol (8b)

2-[(4-Methylbenzyl)sulfanyl]ethanol (9.60 g, 52.7 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (50 mL, dry) to which m-CPBA (18.18 g, 105.0 mmol, 2.0 mol equiv) was added at room temperature with stirring. The reaction was slightly exothermic. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Then 15 min after the addition of m-CPBA, a white solid material precipitated. NaHCO3 (saturated) was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted. The organic layer was extracted with brine and collected, dried (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was recrystallized from ethyl acetate/n-hexane to give the pure material as white crystals (3.11 g). The mother liquor was applied to a silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1/1 (RF = 0.2 and RF = 0.5) to give an additional amount (0.40 g). The total amount obtained was (3.51 g, 31%), mp 102–104 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.30–7.28 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.21–7.19 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 5.29 (1H, br, s, OH), 4.41 (2H, s), 3.82–3.79 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 3.14–3.11 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 2.31 (3H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 137.6, 130.9, 128.9, 125.6, 59.3, 54.9, 53.7, 20.7. IR (KBr): 1697, 1517, 1419, 1296 (s), 1263, 1175, 1116 (s), 1063, 1012, 848, 549, 489 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C10H1403S, 214.0664; found, 214.0665.

1-Bromo-4-[(vinylsulfonyl)methyl]benzene (9a)

2-[(4-Bromobenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanol (2.00 g, 7.17 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL, dry) to which triethylamine (3 mL, 2.18 g, 21.52 mmol, 3.0 mol equiv, anhydrous) was added followed by methylsulfonyl chloride (2 mL, 3.12 g, 19.14 mmol, 2.7 mol equiv) at 0 °C with stirring, which was continued at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was basified with sodium hydrogen carbonate (saturated). The organic layer was collected after the extraction, dried over (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was applied to a silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate/n-hexane (1/2, RF = 0.4). The required product (1.60 g, 86%) was obtained as a white solid, mp 95–97 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.60 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.32 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.96 (1H, dd, J = 16.8 Hz and J = 9.9 Hz), 6.21 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.09 (1H, d, J = 16.6 Hz), 4.55 (2H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 136.2, 133.1, 131.3, 130.5, 128.1, 121.9, 58.0. IR (KBr): 3437, 3057, 2981, 2932, 1489, 1408, 1309, 1260, 1161, 1121, 1072, 1014, 976, 843, 795, 714,519 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C9H979/81BrO2S, 259.9507/261.9486; found, 259.9506/261.9484.

2-[(4-Methylbenzyl)sulfonyl]ethyl Methanesulfonate and 1-Methyl-4-[(vinylsulfonyl)methyl]benzene (9b) and (10b)

2-[(4-Methylbenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanol (3.110 g, 14.51 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL, dry) to which triethylamine (2.202 g, 21.77 mmol, 1.5 mol equiv, anhydrous) was added, followed by methylsulfonyl chloride (2.493 g, 21.77 mmol, 1.5 mol equiv) at 0 °C with stirring, which was continued at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was basified with sodium hydrogen carbonate (saturated). The organic layer was collected after the extraction, dried (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was obtained as a yellow semisolid (5.060 g). TLC showed two spots: RF = 0.3 and RF = 0.6 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1/1). This mixture was used in the next step without further purification.

N-{2-[(4-Bromobenzyl)sulfonyl]ethyl}-N,N-dimethylamine (11a)

1-Bromo-4-[(vinylsulfonyl)methyl]benzene (1.600 g, 6.12 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL, dry) to which dimethylamine (4 mL, 2 M in THF) was added at room temperature with stirring. The stirring was continued at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was extracted with a saturated solution of sodium carbonate. The organic layer was collected, dried over (MgSO4), and filtered, and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure, after which the crude product was applied to a silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate/n-hexane (1/1) in the first instance, followed by ethyl acetate/methanol (9/2, RF = 0.5). The product was obtained as a white solid material (1.36 g, 73%) after trituration with n-hexane, mp 58–60 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.64 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.37 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.52 (2H, s), 3.22 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 2.67 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 2.17 (6H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 133.1, 131.4, 127.9, 121.9, 57.9, 51.6, 49.4, 44.7. IR (KBr): 3424, 2979, 2942, 2822, 2772, 1591, 1488, 1408, 1295, 1275, 1118, 1051, 1013, 843, 816, 640,513 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C11H1679/81BrNO2S, 305.0085/307.0065; found, 305.0081/307.0066.

N,N-Dimethyl-2-[(4-methylbenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanamine (11b)

The product from the previous experiment (4.880 g) was dissolved in DCM (50 mL, dry) to which dimethylamine (4 mL, 2 M in THF) was added at room temperature with stirring. The stirring was continued at room temperature overnight, after which time the reaction mixture was extracted with a saturated solution of sodium carbonate. The organic layer was collected, dried (MgSO4), and filtered, and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was applied to a silica gel column chromatography eluted with ethyl acetate/n-hexane (1/1, RF = 0.1) in the first instance, followed by ethyl acetate/methanol (9/1). The product was obtained as white solid material (2.200 g, 63% based on 2-[(4-methylbenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanol) after trituration with n-hexane, mp 68–70 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.28 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.21 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.44 (2H, s), 3.17 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 2.65 (2H, t, J = 14.3 Hz), 2.31 (3H, s), 2.16 (6H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 137.7, 130.8, 129.0, 125.4, 58.4, 51.6, 49.0, 44.9, 20.7. IR (KBr): 1511, 1463, 1399, 1380, 1314, 1258, 1156, 1119, 1050, 892, 853, 822, 749 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C12H19NO2S, 241.1136; found, 241.1139.

N,N.N-Trimethyl-2-1(4-bromobenzyl)sulfonyl{ethanaminium methane sulfonate (12a)

2-[(4-Bromobenzy)lsulfonyl]ethyl methanesulfonate (0.06g, 0.17 mmol) was suspended in trimethylamine (5 mL in toluene), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature under nitrogen for a period of 5 d, then heated to 60 °C for 20 h. The solvent was concentrated under reduced pressure to give an off-white solid (0.045 g, 83%), mp 187–188 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.66–7.64 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.40–7.38 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.64(2H, s), 3.85–3.80 (2H, m), 3.78–3.74 (2H, m), 3.12 (9H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 133.1, 131.6, 126.3, 121.9, 57.6, 57.4, 52.5, 44.2. IR (KBr): 1591, 1489, 1424, 1413, 1360, 1318, 1277, 1193, 1140, 1068, 1040, 1011, 790, 770 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C12H1979/81BrNO2S, 320.0320/322.0300; found, 320.0321/322.0297.

N,N,N-Trimethyl-2-[(4-methylbenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanaminium Iodide (12b)

N,N-Dimethyl-2-[(4-methylbenzyl)sulfonyl]ethanamine (0.950 g, 3.94 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL, dry) to which iodomethane (4 mL) was added with stirring at room temperature. The stirring was continued overnight. The white solid material formed was filtered off and dried under reduced pressure (1.490 g, 99%), mp 212–214 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.33 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.25 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.58 (2H, s), 3.83–3.79 (2H, m), 3.74–3.71 (2H, m), 3.12 (9H, s), 2.33 (3H, s). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 138.1, 131.0, 129.2, 124.3, 57.9, 57.3, 52.5, 45.0, 18.6. IR (KBr): 1514, 1486, 1326, 1257, 1153, 1123, 1015, 882 cm–1. HRESIMS: calcd for C13H22NO2S, 256.1371; found, 256.1375.

Similarly, the following were prepared: 11c–11p, 12c–12d, 16d–16f, 17d–17f.

N1,N1,N2-Trimethyl-N2-[2-(phenylsulfonyl)ethyl]-1,2-ethanediamine (18a)

(Vinylsulfonyl)benzene (commercially available) (100 mg, 0.60 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (4 mL, dry) to which N1,N1,N2-trimethyl-1,2-ethanediamine (61 mg, 0.062 mL, 0.60 mmol) was added at room temperature with stirring. Stirring was continued at room temperature overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give the required product as a clear pale-yellow oil in quantitative yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.93 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.77 (1H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.68 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 3.49 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.68 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.31 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.13 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.05 (9H, s). IR: 1682, 1606, 1449, 1300, 1199, 1143, 1084, 1037, 744, 731, 689 cm–1. LRESIMS: calcd for C13H23N2O2S, 271.40; found, 271.39.

Similarly, the following were prepared: 18b–18l.

N-[2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl](phenyl)methanesulfonamide (19a)

Phenylmethanesulfonyl chloride [commercially available] (1.034 g, 5.416 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (10 mL, dry) to which N1,N1-dimethyl-1,2-ethanediamine [commercially available] (0.477 g, 5.416 mmol) dissolved in dichloromethane (20 mL, dry) was added dropwise at room temperature with stirring under nitrogen. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 days. The reaction mixture was washed with aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (318 mg, 7.95 mmol in 10 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried (MgSO4), and the solvent removed under reduced pressure to give the required product as a white microcrystalline solid (1.100 g, 84%), mp 127–129 °C, RF = 0.1 [TLC: basic, 99% ethyl acetate and 1% TEA]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.38–7.32 (5H, m), 6.93 (1H, br), 4.35 (2H, s), 2.93 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz), 2.25 (2H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.11 (6H, s). IR [KBr]: 1495, 1458, 1415, 1327, 1261, 1128, 1149, 1050, 893, 784 cm–1. Calculated for C11H18N2O2S: C, 54.52; H, 7.49; N, 11.56; S, 13.23. Found: C, 54.76; H, 7.48; N, 11.62; S, 13.49. HRFABMS: calcd for C11H19O2N2S, 243.1167; found, 243.1169.

Similarly, the following were prepared: 19b–19z.

N-[2-(4-Morpholinyl)ethyl](2-naphthyl)methanesulfonamide (19u)

2-Naphthylmethanesulfonyl chloride (50 mg, 0.208 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (1 mL, dry) to which 2-(4-morpholinyl)ethanamine [commercially available] (27 mg, 34 μL, 0.208 mmol) was added neat dropwise at room temperature with stirring under nitrogen. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was washed with aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (123 mg, 3.08 mmol in 6 mL). The organic layer was separated, dried (MgSO4), and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The product was obtained as a white solid after recrystallization from ethyl acetate/n-hexane (60 mg, 86%), mp 131–134 °C, RF = 0.2 [ethyl acetate only]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.92–7.90 (4H, m), 7.54–7.51 (3H, m), 6.96 (1H, br), 4.55 (2H, s), 3.55 (4H, t, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.05 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.36–2.32 (6H, m). IR (KBr): 1676, 1642, 1594, 1561, 1506, 1462, 1423, 1308, 1174, 1118, 1070, 980, 911, 870, 823, 752, 722 cm–1. Calculated for C17H22N2O3S: C, 61.05; H, 6.63; N, 8.38. Found: C, 61.12; H, 6.73; N, 8.01. HREIMS: calcd for C17H22O3N2S, 334.1351; found, 334.1352.

Similarly, the following were prepared: 19v–19w.

N-Benzylethylenesulfonamide (20a)

Benzylamine (1.275 g, 11.89 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (5 mL, dry) at 0 °C with stirring under N2 to which a solution of 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride (0.969 g, 5.94 mmol) dissolved in DCM (5 mL, dry) was added at 0 °C with stirring under N2, after which time the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction mixture was extracted with dilute hydrochloric acid, and the organic layers were collected, dried (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1/3, RF = 0.2). The product was obtained as colorless oil (390 mg, 33%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.82 (1H, t, J = 6.3 Hz), 7.35–7.25 (5H, m), 6.69 (1H, dd, J = 10.0 and 16.5 Hz), 6.04 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz), 5.95 (1H, d, J = 10.0 Hz), 4.04 (2H, d, J = 6.2 Hz). IR (NaCl): 1497, 1456, 1385, 1327, 1148, 1061, 971, 843, 740 cm–1. Calculated for C9H11NO2S: C, 54.80; H, 5.62; N, 7.10. Found: C, 54.89; H, 5.72; N, 7.04. HRCIMS: calcd for C9H12O2NS, 198.0589; found, 198.0590.

N-Benzyl-2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)ethanesulfonamide: (21a)

Benzylethylenesulfonamide (140 mg, 0.709 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (5 mL, dry) at room temperature to which pyrrolidine (500 mg; 590 μL, 7.09 mmol) was added at room temperature with stirring. The reaction mixture was left standing at room temperature for 48 h. Solvent and excess pyrrolidine were removed under reduced pressure. The white solid material obtained was triturated with n-hexane and filtered to give the required product as a white solid (135 mg, 71%), RF = 0.2 (ethyl acetate/NMM 100/1; basic TLC), mp 100–103 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.60 (1H, t, J = 6.2 Hz), 7.36–7.24 (5H, m), 4.15 (2H, d, J = 6.2 Hz), 3.11 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.71 (2H, t, J = 7.9 Hz), 2.37–2.32 (4H, m), 1.67–1.63 (4H, m). IR (KBr): 1642, 1458, 1331, 1133, 1072, 1017, 870, 761, 738, 705 cm–1. Calculated for C13H20N2O2S: C, 58.18; H, 7.51; N, 10.44. Found: C, 58.03; H, 7.84; N, 10.32. HRFABMS: calcd for C13H21O2N2S, 269.1324; found, 269.1325.

Similarly, the following were prepared: 21b–21r.

N-Phenylethylenesulfonamide (22)

Aniline (1.59 g, 17.12 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL, dry) at 0 °C with stirring under N2 to which NMM (1.73 g; 1.88 mL; 17.12 mmol) was added with stirring. 2-Chloroethanesulfonyl chloride (2.79 g, 1.80 μL, 17.12 mmol) was added at room temperature with stirring under N2. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction mixture was then extracted with dilute hydrochloric acid, and the organic layers were collected, dried (MgSO4), filtered, and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1/3, RF = 0.3). The product was obtained as a light-brown solid (1.918 g, 61%) after trituration with n-hexane, mp 54–57 °C [lit1. mp 64–67 °C; lit.2 mp 65 °C]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.96 (1H, s), 7.31–7.26 (1H, 2, m), 7.15–7.12 (2H, m), 7.08 (1H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 6.79 (1H, dd, J = 10.0 and 16.5 Hz), 6.11 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz), 6.03 (1H, d, J = 10.0 Hz). IR (KBr): 1597, 1488, 1410, 1321, 1218, 1151, 968, 924, 751 cm–1. Calculated for C8H9NO2S: C, 52.44; H, 4.95; N, 7.64. Found: C, 52.33; H, 4.85; N, 7.54. HREIMS: calcd for C8H9NO2S, 183.0354; found, 183.0350.

2-(Dimethylamino)-N-phenylethanesulfonamide69 (23a)

N-Phenylethylenesulfonamide (300 mg, 1.64 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL, dry) to which dimethylamine (2 mL, 2.0 M solution in THF) was added at room temperature with stirring. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Volatile material was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product obtained was applied to a silica gel column chromatography. The product was eluted with ethyl acetate/NMM (100/1), RF = 0.3. The required product was obtained as a white solid after recrystallization from ethyl acetate/n-hexane (340 mg, 91%), mp 68–71 °C [lit. mp 64–65 °C]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 9.77 (1H, br), 7.33–7.06 (5H, m), 3.19 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.62 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 2.05 (6H, s). Calculated for C10H16N2O2S: C, 52.61; H, 7.06; N, 12.27. Found: C, 52.75; H, 7.25; N, 12.14.

Similarly, the following were prepared: 23b–23h.

N-[2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl]-2-phenylacetamide70−72 (24a)

N1,N1-Dimethyl-1,2-ethanediamine (500 mg, 620 μL, 5.67 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (15 mL, dry). Phenylacetyl chloride (877 mg, 5.67 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (15 mL, dry) then added dropwise with stirring at 0 °C to the amine solution. Stirring was continued overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was extracted with sodium hydroxide solution (500 mg in 25 mL of water). The organic layer was collected and dried (MgSO4), and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography using ethyl acetate/NMM/methanol (98/1/1) to give the product as white crystals (0.940 g, 80%), mp 40–42 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.92 (1H, br), 7.29–7.17 (5H, m), 3.38 (2H, s), 3.14 (2H, q, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.27 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.11 (6H, s). IR (KBr): 1652, 1554, 1459, 1354, 1314, 1268, 1188, 1086, 859, 701 cm–1. Calculated for C12H18N2O: C, 69.87; H, 8.80; N, 13.58. Found: C, 69.94; H, 8.84; N, 14.11. HRFABMS: calcd for C12H19N2O, 207.1497; found, 207.1498.

Similarly, the following were prepared: 24b–24e, 25a–25d.

Biological Studies

Mice