Abstract

Adolescence is a unique period of development characterized by enhanced tobacco use and long-term vulnerability to neurochemical changes produced by adolescent nicotine exposure. In order to understand the underlying mechanisms that contribute to developmental differences in tobacco use, this study compared changes in cholinergic transmission during nicotine exposure and withdrawal in naïve adult rats as compared to 1) adolescents and 2) adults that were pre-exposed to nicotine during adolescence. The first study compared extracellular levels of acetylcholine (ACh) in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) during nicotine exposure and precipitated withdrawal using microdialysis procedures. Adolescent (PND 28–42) and adult rats (PND 60–74) were prepared with osmotic pumps that delivered nicotine for 14 days (4.7 mg/kg/day adolescents; 3.2 mg/kg/day adults). Another group of adults was exposed to nicotine during adolescence and then again in adulthood (pre-exposed adults) using similar methods. Control rats received a sham surgery. Following 13 days of nicotine exposure, rats were implanted with microdialysis probes in the NAcc. The following day, dialysis samples were collected during baseline and following systemic administration of the nicotinic-receptor antagonist mecamylamine (1.5 mg/kg and 3.0 mg/kg, IP) to precipitate withdrawal. A second study compared various metabolic differences in cholinergic transmission using the same treatment procedures as the first study. Following 14 days of nicotine exposure, the NAcc was dissected and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity was compared across groups. In order to examine potential group differences in nicotine metabolism, blood plasma levels of cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) were also compared following 14 days of nicotine exposure. The results from the first study revealed that nicotine exposure increased baseline ACh levels to a greater extent in adolescent versus adult rats. During nicotine withdrawal, ACh levels in the NAcc were increased in a similar manner in adolescent versus adult rats. However, the increase in ACh that was observed in adult rats experiencing nicotine withdrawal was blunted in pre-exposed adults. These neurochemical effects do not appear to be related to nicotine metabolism, as plasma cotinine levels were similar across all groups. The second study revealed that nicotine exposure increased AChE activity in the NAcc to a greater extent in adolescent versus adult rats. There was no difference in AChE activity in pre-exposed versus naïve adult rats. In conclusion, our results suggest that nicotine exposure during adolescence enhances baseline ACh in the NAcc. However, the finding that ACh levels were similar during withdrawal in adolescent and adult rats suggests that the enhanced vulnerability to tobacco use during adolescence is not likely related to age differences in withdrawal-induced increases in cholinergic transmission. Our results also suggest that exposure to nicotine during adolescence suppresses withdrawal-induced increases in cholinergic responses during withdrawal. Taken together, this report illustrates important short- and long-term changes within cholinergic systems that may contribute to the enhanced susceptibility to tobacco use during adolescence.

Keywords: Acetylcholine, Nicotine, Withdrawal, Adolescent, Nucleus accumbens

Introduction

Adolescents display high rates of tobacco use initiation and are more likely to continue smoking into adulthood. Surprisingly little is known about the underlying biological mechanisms that promote tobacco use during adolescence and the long-term consequences of adolescent nicotine exposure. During tobacco cessation, withdrawal from nicotine produces a series of biochemical changes characterized by the emergence of negative affective states that promote compulsive tobacco use and relapse [1]. Given the importance of withdrawal in tobacco use, a better understanding of the mechanisms that mediate withdrawal will yield important information that may guide the development of better cessation treatments for smokers of different ages.

Pre-clinical studies have demonstrated that the negative affective states and behavioral signs of nicotine withdrawal are lower during adolescence. For example, nicotine-treated adolescent rats [2, 3] and mice [4] display fewer physical symptoms of withdrawal as compared to adults. Moreover, withdrawal-associated deficits are less pronounced in adolescent versus adult rats in procedures assessing changes in brain reward function and place aversion [2, 5]. These studies suggest that adolescents suffer relatively less severe consequences of nicotine withdrawal than adults.

The mechanisms that mediate nicotine withdrawal appear to involve dopaminergic deficits in the mesolimbic pathway. This pathway originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and terminates in several forebrain structures, including the nucleus accumbens (NAcc). Previous research has shown that nicotine-dependent adult rats display a decrease in extracellular levels of dopamine during withdrawal [6–8]. Recent work in our laboratory demonstrated that adolescent rats display reduced withdrawal-associated deficits in NAcc dopamine versus nicotine-dependent adults [9]. Similarly, nicotine-treated adolescent rats display a reduced decrease in NAcc dopamine following administration of a kappa agonist as compared to adults [10]. Subsequent studies revealed that adolescents are resistant to the decreases in NAcc dopamine produced by withdrawal because of enhanced excitation via glutamate and reduced inhibition via gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) on dopamine cell bodies in the VTA [11]. These studies suggest that age differences produced by nicotine withdrawal are mediated, in part, by dopamine transmission in the mesolimbic pathway.

There is also evidence suggesting that cholinergic transmission in the NAcc is altered during nicotine withdrawal. Specifically, adult rats experiencing nicotine withdrawal display an increase in extracellular levels of acetylcholine (ACh) in the NAcc [8]. This effect is also observed during withdrawal from amphetamine, cocaine, ethanol and morphine [12, 13]. Conditioned taste aversion and mild stress also increase NAcc ACh, while lowering dopamine in this region [14]. These findings suggest that increases in ACh and decreases in dopamine in the NAcc serve as biomarkers of negative affective states produced by withdrawal from drugs of abuse.

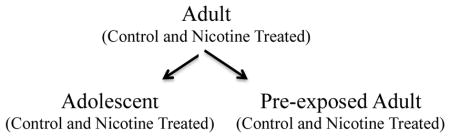

To our knowledge, no one has compared cholinergic transmission in the NAcc during nicotine withdrawal in adolescent and adult rats. Moreover, the long-term effects of adolescent nicotine exposure on cholinergic transmission in the NAcc have not been studied during nicotine exposure or withdrawal from this drug. To address these issues, the present study essentially conducted a series of two-group comparisons between adult rats and either 1) adolescents or 2) adults that were exposed to nicotine during adolescence (pre-exposed adults). Within each experimental group, the rats were either nicotine-treated or received a sham pump surgery. The first study compared extracellular levels of ACh in the NAcc during nicotine exposure and withdrawal. In order to determine whether group differences in nicotine metabolism may have influenced our results, a second study compared blood plasma levels of cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) following 14 days of nicotine exposure. This study also compared acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity levels as a metabolic marker of cholinergic transmission across our experimental groups.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Male Wistar rats (n=4–12 per group) were used. The adolescents were approximately postnatal day (PND) 28 and the adults were PND 60 at the time of the pump implantation surgery. All rats were given free access to food and water throughout the study. Rats were pair-housed in a humidity- and temperature-controlled (20–22°C) vivarium using a 12-hr light/dark cycle with lights on at 8:00 PM. The home cage consisted of a rectangular Plexiglas hanging cage (41.5 cm long 31.7 cm wide 32.1 cm high) with pine bedding. The food and water were located above the animals’ living space on a wire platform encased within a filtered cover. The animals were bred in the animal vivarium of the Psychology Department from a stock of outbred rats from Harlan, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). The rats were bred onsite in order to minimize stress that might have occurred in the adolescents if they had been shipped and tested too close to their weaning period. All procedures were approved by the University of Texas at El Paso Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs

(−) Nicotine-hydrogen tartrate and mecamylamine hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Mecamylamine was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline and injected intraperitoneally (IP) in a volume of 1 ml/kg. All drugs were administered at physiological pH of 7.2–7.4.

Surgical procedures

The rats were first anesthetized with an isofluorane/oxygen mixture (1–3% isofluorane). They were then prepared with 14-day osmotic pumps that were implanted subcutaneously parallel to the spine (Alzet model 2ML2; 1.0 μl/h; Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA). The pumps were filled with nicotine (4.7 mg/kg/day for adolescents or 3.2 mg/kg/day for adults; expressed as base). The adolescents were exposed to nicotine between PND 28–42 and adults were exposed between PND 60–74. A separate group of rats received 14 days of nicotine exposure during adolescence (4.7 mg/kg/day) and then received another 14 days of nicotine exposure later during adulthood (3.2 mg/kg/day). The nicotine pump was surgically removed after 14 days of exposure during adolescence to ensure the same level of nicotine exposure across experimental conditions. The naïve (not pre-exposed) adults received a sham surgery during adolescence to control for the influence of the surgical procedures that may have influenced our comparisons to the pre-exposed adults. The concentration of nicotine in the pump was adjusted according to the weight of the rat at the time of the surgery. The nicotine concentrations were based on previous studies showing that adolescent rats require approximately 1.5 times more nicotine to produce similar plasma nicotine levels as adults [2, 15]. Following implantation, the incision was closed with 9-mm stainless steel wound clips and treated with a topical antibiotic ointment.

Experimental groups

The controls for each group received a sham surgery and were not exposed to nicotine. Our experimental approach essentially involved a two-group comparison between adult rats and either 1) adolescents or 2) adults that were exposed to nicotine during adolescence (pre-exposed adults). The experimental conditions were as follows:

Study 1: Cholinergic transmission in the NAcc during nicotine withdrawal

Microdialysis procedures

Thirteen days after pump implantation, the rats were re-anesthetized and stereotaxically implanted with microdialysis probes aimed at the NAcc. The probes were purchased from CMA-Microdialysis (model CMA 12; 20KD; Holliston, MA) with an active membrane length of 2 mm. The probes were perfused for at least 1 hr prior to implantation at a rate of 0.5 μl/min with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) composed of 145 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 5.4 mM d-glucose and 0.25 mM ascorbic acid (adjusted to a pH of approximately 7.2). The probes were implanted into the NAcc using the following coordinates from bregma [adolescent = anterior-posterior (AP) +2.2, medial-lateral (ML)±0.8, dorsal-ventral (DV) −7.1 and adult = AP +1.7, ML ±1.4, DV −8.1]. The placements were derived from our previous studies using these age ranges [9]. The hemisphere that was implanted with the probe was counterbalanced to control for possible hemispheric differences across experimental conditions. Following surgery, the rats were individually housed in a similar-sized test cage as their home cage with food and water available throughout the following test day.

After surgery, the perfusate flow rate was maintained at 0.2 μl/min overnight. The next morning, the flow rate was increased to 1.5 μl/min for 1 hr to allow for equilibration of the probes. Dialysate samples were then collected in 10-min intervals for 1-hr sampling periods during baseline and then following systemic administration of saline and then 2 doses of mecamylamine (1.5 and 3.0 mg/kg; IP; expressed as salt). The doses of mecamylamine were chosen based on previous studies demonstrating age differences in dopamine transmission produced by nicotine withdrawal [9, 11]. After collection, each sample was immediately frozen on dry ice and then stored at −80°C until they were analyzed 1–2 weeks later.

ACh analysis

ACh was separated by a 12-cm reverse phase ESA ACh-3 analytical column at 38°C. The ACh was converted to hydrogen peroxide and betaine by an ESA ACh solid phase reactor containing acetylcholinesterase and choline oxidase. The estimation of ACh levels was assessed by electrochemical detection, as described in [16]. Mobile phase was pumped through the system at a pump speed of 0.35 ml/min. The mobile phase contained 100 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM trimethylammonium chloride, 0.005% Reagent MB (ESA) and 20 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid (Sigma Aldrich, Inc.), which was adjusted to a pH of 8.0 with 85% H3PO4 and degassed through a 0.2-μm filter. ACh levels were quantified with a model 5040 ESA analytical cell with a platinum target electrode set at +300 mV. The EC detector range (ESA Coulochem II) was set to 2 nA for ACh detection with a 10-s filter. Peaks were analyzed and recorded on a computerized data capture system. The detection limit for ACh was 7 fmol/min/10-μl. Peak identities were verified by their absence following removal of the solid phase reactor column.

Histological verification of probe placements

At the end of the experiment, the rats were sacrificed and the brains were frozen on dry ice. The probe placements were verified from coronal sections of the NAcc. In order to be included in the neurochemical analysis, the probe placements had to fall within the NAcc and the animals’ baseline values had to fall within 2 standard deviations from the group mean.

Study 2: Metabolic markers of cholinergic transmission in the NAcc during withdrawal

AChE activity assay

A separate group of rats received the same nicotine pump exposure as Study 1. Fourteen days after pump implantation, the rats were sacrificed and the brains were placed in ice-cold phosphate (Na) buffer at a pH of 8.0 containing 0.02 M MgCl2. Once each brain was cooled, the NAcc was quickly dissected on a cooled petri dish that was kept on ice. The NAcc tissue was then weighed and frozen at −80°C until the samples were analyzed within the next couple of days. The AChE assays were conducted according to the spectrophotometric method of [17] except at pH 7.4. The NAcc was homogenized as a 16.7% w/v (1:6 w/v) in 0.1 M (Na) PO4 in a ground glass tissue homogenizer. The homogenate was then diluted 1:10 (1:60 total dilution) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and that suspension was used as the source of AChE activity. A 150-μl aliquot of the 1:60 dilution of brain homogenate was added to 150 μl of Ellman’s reagent and 4.0 ml of additional PBS. Finally, 290 μl of the AChE/Ellman’s mixture was added into each well of a 96-well plate. The AChE reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 μl of acetylthiocholine Br solution (30 mM, 6 mM or 3 mM) to make a final volume of 300 μl in each well, which made a 1 cm light path. The final concentrations of the acetylthiocholine substrates in the wells were 3.3 μM, 6.67 μM or 33.3 μM and the change in absorbance at 412 nm was recorded for 4 min. In this assay, the final enzyme dilution was 1:1781 w/v from wet weight tissue. Blanks were run using HPLC water instead of substrate. Km and Vmax values were calculated by least squares linear regression of 1/V versus 1/[S]. Finally, enzyme activity was expressed in moles of substrate converted min−1 gram−1 of wet weight tissue using Ellman’s extinction coefficient.

Cotinine assay

Trunk blood was collected at the time the rats were sacrificed. The blood was collected into test tubes and the plasma was separated from the whole blood via centrigugation at 2,000 RPM. The plasma was then separated and cotinine levels were analyzed using a commercially available 96-well plate ELISA kit from OraSure Technologies, Inc. (Bethlehem, PA). The cotinine levels were estimated from internal standards using a Spectra Maxplus spectrophotometer from Molecular Devices, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0 (Armonk, NY). Our statistical approach involved overall ANOVAs followed by post-hoc testing where appropriate using Fisher’s LSD tests (p<0.05). The data in Figures 1 and 3 (basal ACh and AChE activity) were analyzed using ANOVA with treatment (control versus nicotine) and experimental group (adult, adolescent and pre-exposed adult) as between subject factors. The data in Figure 2 (ACh levels) were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA with time as a within subject factor and treatment and age group as between subject factors. The experimental approach of this study is essentially a two-group comparison between adult rats and either 1) adolescents or 2) pre-exposed adults. Given that the data for all of the groups are presented in each figure, our statistics involved a conservative approach whereby all of the experimental groups were included in an overall analysis. If a significant interaction was observed, then separate post-hoc analyses were conducted within each sampling period (Figure 2) or treatment group (Figure 3). The data in Figure 4 (cotinine levels) were analyzed using one-way ANOVA across age groups. Within each figure, different symbols were used to denote the different group comparisons that were made. For example, asterisks (*) denote a significant difference from respective controls and daggers (†) denote a difference from adult rats.

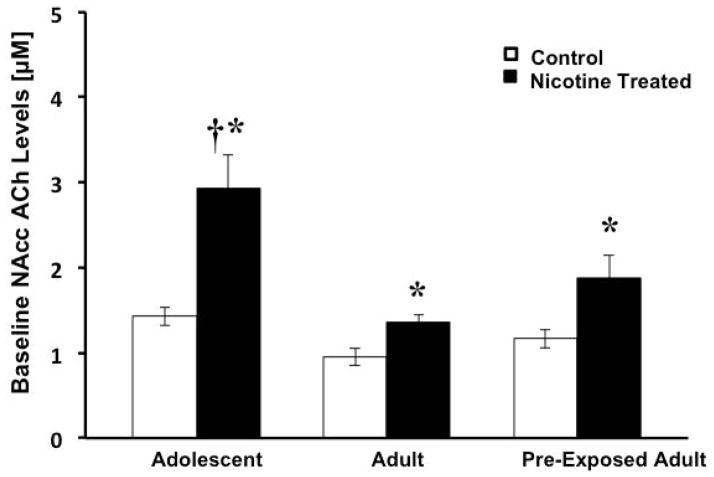

Fig. 1.

The data reflect baseline levels of ACh (±SEM) in the NAcc of adolescent (control n=6 and nicotine-treated n=7), adult (control n=6 and nicotine-treated n=6) and pre-exposed adult rats control n=4 and nicotine-treated n=8). Asterisks (*) denote a main effect of nicotine treatment relative to controls and the dagger (†) denotes a significant difference from adult rats (p<0.05).

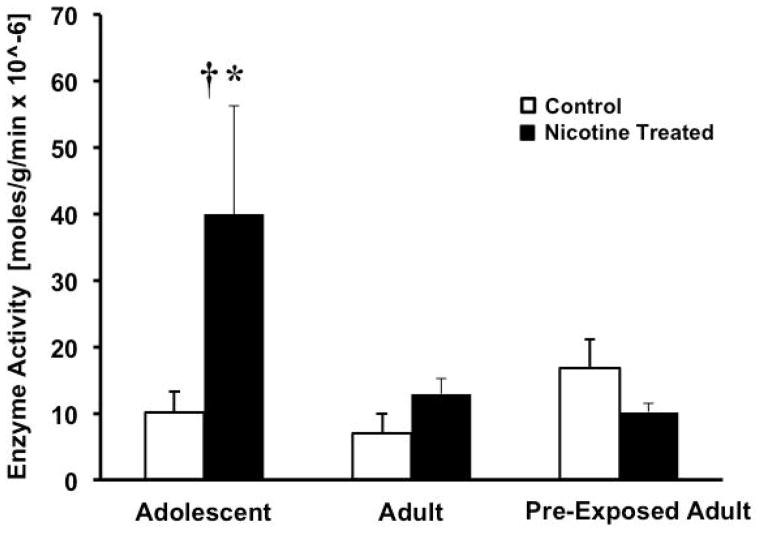

Fig. 3.

The data reflect AChE activity [moles/g/min × 10−6] (±SEM) in the NAcc of adolescent (control n=7 and nicotine-treated n=7), adult (control n=9 and nicotine-treated n=7) and pre-exposed adult rats (control n=8 and nicotine-treated n=6). The asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference relative to controls and the dagger (†) denotes a significant difference from adults (p<0.05).

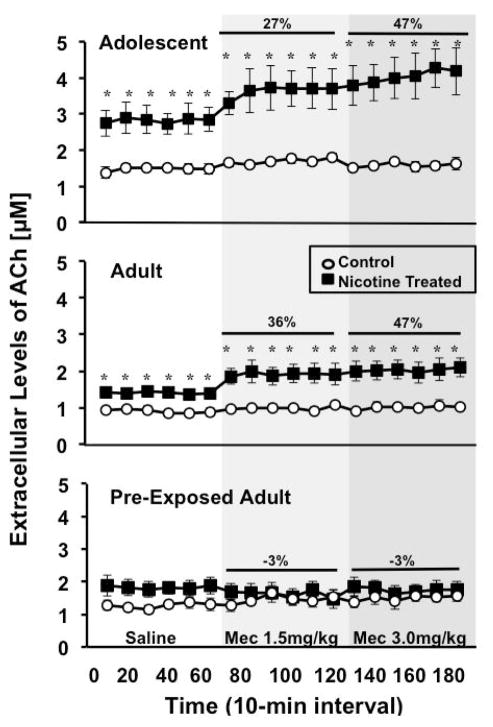

Fig. 2.

The data reflect extracellular levels of ACh (±SEM) in the NAcc of adolescent (control n=6 and nicotine-treated n=7), adult (control n=6 and nicotine-treated n=6) and pre-exposed adult rats control n=4 and nicotine-treated n=8). Each point reflects a 10-min sampling period following saline administration and then administration of 2 doses of mecamylamine (1.5 and 3.0 mg/kg) to precipitate withdrawal (shaded areas). Asterisks (*) denote a significant difference from respective controls (p<0.05).

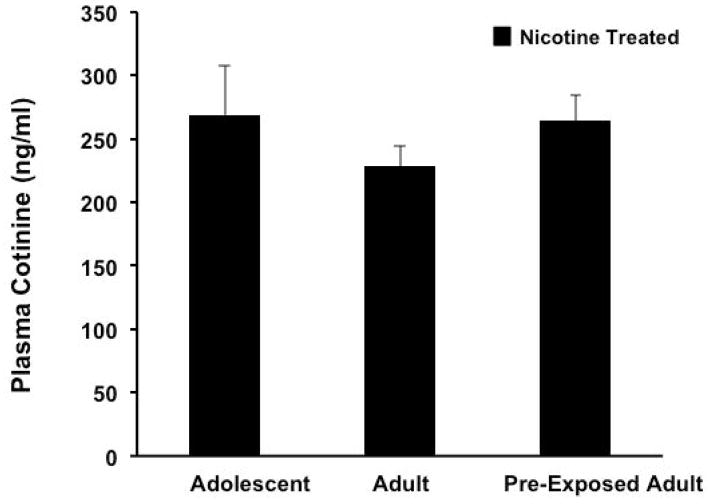

Fig. 4.

The data reflect plasma cotinine levels (ng/ml) (±SEM) in the NAcc of nicotine-treated adolescent (n=8), adult (n=11) and pre-exposed adult rats (n=12).

Results

Study 1

Baseline ACh

Figure 1 denotes baseline levels of ACh in the NAcc of control and nicotine-treated adolescent, adult and pre-exposed adult rats. Overall, the results revealed that nicotine-treatment increased baseline ACh as compared to controls, an effect that was highest in adolescent rats. There was no interaction between treatment and experimental conditions (F2,31=2.6; p=ns). However, there was a main effect of treatment (F1,31=18.2; p<0.001), illustrating that nicotine exposure produced an increase in baseline ACh regardless of age group (p<0.05). There was also a main effect of experimental group (F1,31=9.0; p<0.001), with nicotine-treated adolescents displaying higher basal ACh as compared to both adult groups, regardless of nicotine pre-exposure (p<0.05). There were no differences in control rats across experimental groups.

Withdrawal-induced changes in ACh

Figure 2 depicts ACh in the NAcc of control and nicotine-treated adolescent, adult and pre-exposed adult rats. Overall, the results revealed that nicotine withdrawal produced an increase in ACh in adolescent rats (37% average increase) that was similar to naïve adults (41% average increase); however, this effect was absent in pre-exposed adult rats. The overall analysis revealed a significant interaction between treatment and experimental group (F2,31=30.15; p<0.05). The post-hoc analyses revealed that nicotine-treated adolescents and adults displayed an increase in ACh as compared to control rats during each sampling period (p<0.05). However, this effect was not observed in pre-exposed adults. There were no differences in control rats across experimental groups.

Study 2

AChE activity

Figure 3 depicts AChE activity in the NAcc of adolescent, adult and pre-exposed adult rats. The results revealed that nicotine-treated adolescents displayed an increase in AChE activity that was higher than both groups of adult rats, regardless of nicotine pre-exposure. The analysis revealed a significant interaction between treatment and experimental conditions (F2,33=4.19; p< 0.05), with nicotine-treated adolescent rats displaying higher AChE activity levels as compared to control rats (p<0.05) and relative to both adult groups (p<0.05). There were no differences in control rats across experimental conditions.

Cotinine levels

Figure 4 depicts cotinine levels (ng/ml±SEM) in blood plasma collected from nicotine-treated adolescent, adult and pre-exposed adult rats. The results revealed that there were no significant differences in cotinine levels across experimental groups after 14 days of nicotine exposure (F2,27= 0.89; p=ns).

Discussion

Summary

A major finding of this report is that nicotine exposure produced an increase in basal levels of ACh in the NAcc that was largest in adolescent rats as compared to adults. Another important finding is that under withdrawal conditions, an increase in ACh was observed in the NAcc that was similar in adolescent and naïve adult rats. Interestingly, the latter effect was absent in adult rats that were exposed to nicotine during adolescence. These finding suggest that adolescence is a unique period of development characterized by 1) a short-term increase in cholinergic transmission produced by nicotine exposure during adolescence and 2) a long-term suppression of cholinergic responses during withdrawal in adult rats that were exposed to nicotine during adolescence.

The role of ACh in the process of nicotine addiction

The process of tobacco addiction involves activation of nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChRs) that consist of specific subunit configurations, such as α4β2 and α7 [18]. Regarding the initial acquisition of nicotine use, a pre-clinical report demonstrated that blockade of nAChRs in the NAcc disrupts the development of drug-seeking behavior in rats [19]. Thus, the initial phases of acquisition of tobacco use likely involve nAChRs in the NAcc. Following chronic drug use, pre-clinical studies have demonstrated a dysregulation in brain reward mechanisms, including but not limited to changes in nAChRs and ACh release in the NAcc. For example, a neurochemical “marker” of nicotine withdrawal is increased ACh levels in the NAcc [8]. Increased ACh levels are also observed during withdrawal from other drugs such as, amphetamine, cocaine, ethanol and morphine [20, 21]. Further, conditioned taste aversion and mild stress also increase NAcc ACh levels, while lowering dopamine levels in this region [22]. These findings suggest that increases in ACh combined with a decrease in dopamine levels in the NAcc serve as biomarkers of withdrawal from nicotine. The present study contributes to this literature by examining changes in cholinergic systems in the NAcc following nicotine exposure and withdrawal from this drug during the adolescent period (short-term effects) and later in adulthood following exposure to nicotine during adolescence (long-term changes).

Short-term effects of nicotine exposure and withdrawal during adolescence

Pre-clinical studies have revealed that there are fundamental differences in the mechanisms that drive nicotine use among adolescents and adults [23–25]. The present study extends previous work by demonstrating that adolescent nicotine exposure produces an increase in basal cholinergic transmission, and that the increases in ACh produced by nicotine withdrawal are similar across age groups. Studies in other laboratories have compared changes in nAChRs nicotine exposure in adolescent and adult rats. This work has revealed that the changes in nAChRs are age-, sex-, receptor subtype- and region-dependent [26–29]. As an example, one report demonstrated that across several brain regions α4β2 and α7 nAChRs were more prominently increased following nicotine exposure in adult versus adolescent rats [28]. However, another report demonstrated a more prominent increase across several brain regions in nAChRs following nicotine exposure in adolescent versus adult rats [29]. Our results suggest that one potential mechanism for the changes in nAChRs may involve age-dependent changes in cholinergic tone following nicotine exposure. This is based on our finding that nicotine exposure produced a larger basal increase in ACh levels and AChE activity in adolescent versus adult rats. The implications of these effects with regard to enhanced vulnerability to tobacco use during adolescence warrants future investigation using animal models of nicotine dependence in rodents of different ages.

Much work has shown that the behavioral effects of nicotine withdrawal are lower in adolescent versus adult rodents [25]. Previous work in our laboratory suggests that dopamine systems modulate age differences produced by nicotine withdrawal. This is based on our finding that nicotine-treated adult rats displayed a robust decrease in NAcc dopamine levels during withdrawal that was absent in adolescents [9]. Nicotine-treated adult rats also displayed a smaller decrease in NAcc dopamine in adolescents versus adults following administration of a kappa opiate receptor agonist [10]. Subsequent studies revealed that adolescents shown smaller decreases in NAcc dopamine during withdrawal because of enhanced excitation via glutamate and reduced inhibition via GABA on dopamine cell bodies in the VTA [11]. The present findings suggest that age differences produced by nicotine withdrawal are not likely modulated via cholinergic transmission in the NAcc. Collectively, our research suggests that age differences produced by nicotine withdrawal are modulated, in large part, via dopaminergic transmission in the mesolimbic pathway.

Long-term effects of adolescent nicotine exposure and withdrawal later in adulthood

There is a large body of literature showing that developmental exposure to nicotine produces an array of behavioral and neurological consequences, especially during the neonatal period [30]. Within this literature, the long-term effects of adolescent nicotine exposure are complex and vary depending on what is measured. With regard to behavioral changes, rodent studies have demonstrated that adolescent nicotine exposure increases the rewarding effects of nicotine later in adulthood [31–33]. However, recent work in our laboratory demonstrated that adolescent nicotine exposure ameliorated the food suppressant effects of nicotine later in adulthood [33]. Also, exposure to nicotine during adolescence enhances anxiety-like behavior [34], but abolishes the corticosterone-activating effect of nicotine later in adulthood [35]. The present study revealed that withdrawal-induced increases in ACh were blunted following exposure to nicotine during adolescence. Consistent with this, gestational nicotine exposure produced a long-term suppression of nicotine-induced increases in NAcc dopamine levels [36]. Adolescent nicotine exposure also produced a long-term suppression of nicotine-induced increases in striatal dopamine and norepinephrine [37]. Our plasma cotinine data rule out the possibility that the blunted neurochemical effects observed in pre-exposed adults are related to group differences in nicotine metabolism. Another possibility is that adolescent nicotine exposure may have produced neurotoxicity that leads to a blunted neurochemical response during nicotine withdrawal. This idea is based on the finding that adolescent nicotine exposure produces greater neuroteratogenicity as compared to exposure to this drug during adulthood [38]. These findings have led researchers to question the use of nicotine replacement therapy in adolescent smokers [39]. Future studies are needed to examine the mechanisms that modulate our neurochemical effects.

Clinical implications

Our findings have important implications toward developing more effective cessation strategies for smokers of different ages and previous exposure to nicotine. Our data suggests that adolescent nicotine exposure produces long-term changes in cholinergic systems that may reduce the efficacy of smoking cessation medications later in adulthood, such as nicotine replacement therapy. Consistent with this suggestion, clinical studies in adolescents have found that long-term abstinence rates are not closely associated with nicotine replacement therapies [40–42]. With regard to the long-term consequences of nicotine, our data suggest that adolescent nicotine exposure promotes the dysregulation of cholinergic systems that confer drug dependence. This includes enhancing the rewarding effects of nicotine and possibly altering the aversive effects of nicotine withdrawal. Thus, putting a nicotine patch on an adolescent may be harmful because it might facilitate the development of dependence in young tobacco users who do not normally experience nicotine withdrawal. Future studies are needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms that confer enhanced vulnerability to nicotine in an adult that was exposed to nicotine during adolescence. Future studies might also consider the role of sex differences, environmental conditions and prior drug history in developmental differences to nicotine use.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the technical assistance of Ivan Torres. This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA021274), the Diversity-promoting Institutions Drug Abuse Research Program (R24-DA029989) and the Research Experience for Undergraduates Training Program (R25-DA033613). This project was also supported by the National Institute of Minority Health Disparities (G12MD007592) as part of the UTEP Border Biomedical Research Center. Dr. Luis Natividad was supported by the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein Fellowship Program (F31-DA021133) and the APA Diversity Program in Neuroscience (T32-MH018882).

References

- 1.Dani JA, Jenson D, Broussard JI, De Biasi M. Neurophysiology of nicotine addiction. J Addict Res Ther. 2011;20(1):S1. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.S1-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Dell LE, Bruijnzeel AW, Smith RT, Parsons LH, Merves ML, Goldberger BA, Koob GF, Markou A. Diminished nicotine withdrawal in adolescent rats: implications for vulnerability to addiction. Psychopharmacol. 2006;186:612–619. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shram MJ, Siu EC, Li Z, Tyndale RF, Lê AD. Interactions between age and the aversive effects of nicotine withdrawal under mecamylamine-precipitated and spontaneous conditions in male Wistar rats. Psychopharmacol. 2008;198:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kota D, Martin BR, Robinson SE, Damaj MI. Nicotine dependence and reward differ between adolescent and adult male mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:399–407. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Dell LE, Torres OV, Natividad LA, Tejeda HA. Adolescent nicotine exposure produces less affective measures of withdrawal relative to adult nicotine exposure in male rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carboni E, Bortone L, Giua C, Di Chiara G. Dissociation of physical abstinence signs from changes in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and in the prefrontal cortex of nicotine dependent rats. Drug Alc Dep. 2000;58:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hildebrand BE, Nomikos GG, Hertel P, Schilstrom B, Svensson TH. Reduced dopamine output in the nucleus accumbens but not in the medial prefrontal cortex in rats displaying a mecamylamineprecipitated nicotine withdrawal syndrome. Brain Res. 1998;779:214–225. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rada P, Jensen K, Hoebel BG. Effects of nicotine and mecamylamine-induced withdrawal on extracellular dopamine and acetylcholine in the rat nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacol. 2001;157:105–110. doi: 10.1007/s002130100781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Natividad LA, Tejeda HA, Torres OV, O’Dell LE. Nicotine withdrawal produces a decrease in extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens that is lower in adolescent versus adult male rats. Synapse. 2010;64(2):136–145. doi: 10.1002/syn.20713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tejeda HA, Natividad LA, Orfila JE, Torres OV, O’Dell LE. Dysregulation of kappa-opioid receptor systems by chronic nicotine modulate the nicotine withdrawal syndrome in an age-dependent manner. Psychopharmacol. 2012;224:289–301. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2752-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natividad LA, Parsons LH, OV, O’Dell LE. Adolescent rats are resistant to adaptations in excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms that modulate mesolimbic dopamine during nicotine withdrawal. J Neurochem. 2012;123:578–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rada P, Johnson DF, Lewis MJ, Hoebel BG. In alcohol-treated rats, naloxone decreases extracellular dopamine and increases acetylcholine in the nucleus accumbens: evidence of opioid withdrawal. Pharmacol Biochem Beh. 2004;79:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossetti ZL, Hmaidan Y, Gessa GL. Marked inhibition of mesolimbic dopamine release: a common feature of ethanol, morphine, cocaine and amphetamine abstinence in rats. Euro J Pharmacol. 1992;221:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90706-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark GP, Weinberg JB, Rada PV, Hoebel BG. Extracellular acetylcholine is increased in the nucleus accumbens following the presentation of an aversively conditioned taste stimulus. Brain Res. 1995;688(1–2):184–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00401-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trauth JA, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. An animal model of adolescent nicotine exposure: effects on gene expression and macromolecular constituents in rat brain regions. Brain Res. 2000;867:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damsma G, Westerink BHC. A microdialysis and automated on-line analysis approach to study central cholinergic transmission in vivo. In: Robinson TE, Justice JB, editors. Microdialysis in the Neurosciences. Elsevier; New York: 1991. pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Feather-Stone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penton RE, Lester RA. Cellular events in nicotine addiction. Seminars Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20(4):418–431. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crespo JA, Stockl P, Zorn K, Saria A, Zernig G. Nucleus accumbens core acetylcholine is preferentially activated during acquisition of drug- vs food-reinforced behavior. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;33:3213–3220. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rada P, Johnson DF, Lewis MJ, Hoebel BG. In alcohol-treated rats, naloxone decreases extracellular dopamine and increases acetylcholine in the nucleus accumbens: evidence of opioid withdrawal. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79(4):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossetti ZL, Hmaidan Y, Gessa GL. Marked inhibition of mesolimbic dopamine release: a common feature of ethanol, morphine, cocaine and amphetamine abstinence in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;221(2–3):227–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90706-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mark GP, Weinberg JB, Rada PV, Hoebel BG. Extracellular acetylcholine is increased in the nucleus accumbens following the presentation of an aversively conditioned taste stimulus. Brain Res. 1995;688(1–2):184–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00401-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adriani W, Laviola G. Windows of vulnerability to psychopathology and therapeutic strategy in the adolescent rodent model. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15:341–352. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barron S, White A, Swartzwelder HS, Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Slawecki CJ, Ehlers CL, Levin ED, Rezvani AH, Spear LP. Adolescent vulnerabilities to chronic alcohol or nicotine exposure: findings from rodent models. Alc Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1720–1725. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000179220.79356.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Dell LE. A psychobiological framework of the substrates that mediate nicotine use during adolescence. Neuropharmacol. 2009;56(1):263–278. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins SL, Wade D, Ledon J, Izenwasser S. Neurochemical alterations produced by daily nicotine exposure in periadolescent vs. adult male rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;502(1–2):75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Counotte DS, Goriounova NA, Moretti M, Smoluch MT, Irth H, Clementi F, Schoffelmeer AN, Mansvelder HD, Smit AB, Gotti C, Spijker S. Adolescent nicotine exposure transiently increases high-affinity nicotinic receptors and modulates inhibitory synaptic transmission in rat medial prefrontal cortex. FASEB J. 2012;26(5):1810–1820. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-198994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doura MB, Gold AB, Keller AB, Perry DC. Adult and periadolescent rats differ in expression of nicotinic cholinergic receptor subtypes and in the response of these subtypes to chronic nicotine exposure. Brain Res. 2008;1215:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trauth JA, Seidler FJ, McCook EC, Slotkin TA. Adolescent nicotine exposure causes persistent upregulation of nicotinic cholinergic receptors in rat brain regions. Brain Res. 1999;851(1–2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winzer-Serhan UH. Long-term consequences of maternal smoking and developmental chronic nicotine exposure. Front Biosci. 2008;13:636–649. doi: 10.2741/2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adriani W, Deroche-Gamonet V, Le Moal M, Laviola G, Piazza PV. Pre-exposure during or following adolescence differently affects nicotine-rewarding proper-ties in adult rats. Psychopharmacol. 2006;184:382–390. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin ED, Rezvani A, Montoya R, Rose J, Swartrzwelder H. Adolescent-onset nicotine self-administration modeled in female rats. Psychopharmacol. 2003;169:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1486-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natividad LA, Torres OV, Friedman TC, O’Dell LE. Adolescence is a period of development characterized by short- and long-term vulnerability to the rewarding effects of nicotine and reduced sensitivity to the anorectic effects of this drug. Behav Brain Res. 2013;257:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith LN, McDonald CG, Bergstrom HC, Brielmaier JM, Eppolito AK, Wheeler TL, Falco AM, Smith RF. Long-term changes in fear conditioning and anxiety-like behavior following nicotine exposure in adult versus adolescent rats. Pharmacol Biochem Beh. 2006;85(1):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz FC, Delucia R, Planeta CS. Differential behavioral and neuroendocrine effects of repeated nicotine in adolescent and adult rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80(3):411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kane VB, Fu Y, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Gestational nicotine exposure attenuates nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens shell of adolescent Lewis rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308(2):521–528. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trauth JA, Seidler FJ, Ali SF, Slotkin TA. Adolescent nicotine exposure produces immediate and long-term changes in CNS noradrenergic and dopaminergic function. Brain Res. 2001;892(2):269–280. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ginzel KH, Maritz GS, Marks DF, Neuberger M, Pauly JR, Polito JR, Schulte-Hermann R, Slotkin TA. Critical review: nicotine for the fetus, the infant and the adolescent? J Health Psychol. 2007;12(2):215–224. doi: 10.1177/1359105307074240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slotkin TA, Bodwell BE, Ryde IT, Seidler FJ. Adolescent nicotine treatment changes the esponse of acetylcholine systems to subsequent nicotine administration in adulthood. Brain Res Bull. 2008;76(1–2):152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanson KA, Allenn S, Jensen S, Hatsukami D. Treatment of adolescent smokers with the nicotine patch. Nic Tob Res. 2003;5:515–526. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurt RD, Croghan GA, Beede SD, Wolter TD, Croghan IT, Patten CA. Nicotine patch therapy in 101 adolescent smokers: efficacy, withdrawal symptom relief, and carbon monoxide and plasma cotinine levels. Arch Ped Adol Med. 2000;154:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moolchan ET, Robinson ML, Ernst M, Cadet JL, Pickworth WB, Heishman SJ, Schroeder JR. Safety and efficacy of the nicotine patch and gum for the treatment of adolescent tobacco addiction. Pediatrics. 2005;115:407–414. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]