Abstract

Molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE) is integrative molecular and population health science to address molecular pathogenesis and heterogeneity of disease processes. MPE of colon and rectal premalignant lesions (including hyperplastic polyps, tubular adenomas, tubulovillous adenomas, villous adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, sessile serrated adenomas / sessile serrated polyps, and hamartomatous polyps) can provide unique opportunities to examine the influence of diet, lifestyle and environmental exposures on specific pathways of carcinogenesis. Colorectal neoplasia can provide a practical model where both malignant epithelial tumor (carcinoma), and its precursor, are subjected to molecular pathology analyses. KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA oncogene mutations, microsatellite instability, CpG island methylator phenotype, and LINE-1 methylation are commonly-examined tumor biomarkers. Future opportunities include comprehensive interrogation of genomics, epigenomics and pan-omics, as well as in vivo pathology analyses of tissue microenvironment, molecular networks and interactome by endomicroscopy. Considering the colorectal continuum hypothesis and emerging roles of gut microbiota and host immunity in tumorigenesis, detailed tumor location is important information. There are unique strengths and caveats, especially with regard to case ascertainment by colonoscopy. MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions can identify etiologic exposures associated with neoplastic initiation and progression, help us better understand colorectal carcinogenesis, and facilitate personalized prevention, screening, and therapy.

Keywords: molecular pathological epidemiology, colorectal cancer, adenoma, polyp, serrated neoplasia, unique tumor principle, CIMP

Introduction – The Evolving MPE Paradigm

Colorectal tumors represent a heterogenous group of diseases that arise and evolve through the stepwise accumulation of differing sets of genetic and epigenetic alterations (1). In addition to tumor factors, host components, consisting of extracellular matrix and non-transformed cells, interact with tumor cells and play major roles in regulating tumor growth and behavior (2, 3). The molecular complexity of colorectal neoplasia poses challenges to conventional epidemiologic research, where disease heterogeneity is not often taken into consideration in analyses. Molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE), the integration of molecular pathology and epidemiology (4, 5), was conceived to address disease heterogeneity by examining the association between etiologic factors and specific molecular signatures generated during disease processes (4–9). MPE differs from conventional molecular epidemiology, where patients with a disease of interest are typically lumped together into a single disease entity, in that MPE embraces the inherent molecular heterogeneity of disease and the uniqueness of each patient (10) (Figure 1). MPE can therefore be defined as the “epidemiology of molecular pathology and heterogeneity of disease” (11). The MPE paradigm offers several advantages over conventional epidemiologic approaches. By helping decipher relationships between specific etiologic exposures and molecular disease subtypes, MPE studies can provide evidence to support the causality of associations (4, 5). Moreover, MPE can help refine risk estimates for disease occurrence, recurrence, or progression in particular patient subgroups, which can contribute to personalized prevention and treatment strategies(12–14). Indeed, the utility of the MPE concept has been widely acknowledged (6–9, 15–38), and has resulted in a number of important insights into the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer, including associations between obesity, physical activity, and aspirin use, and risks of disease occurrence or survival for molecularly-defined colorectal cancer subgroups (12–14, 39).

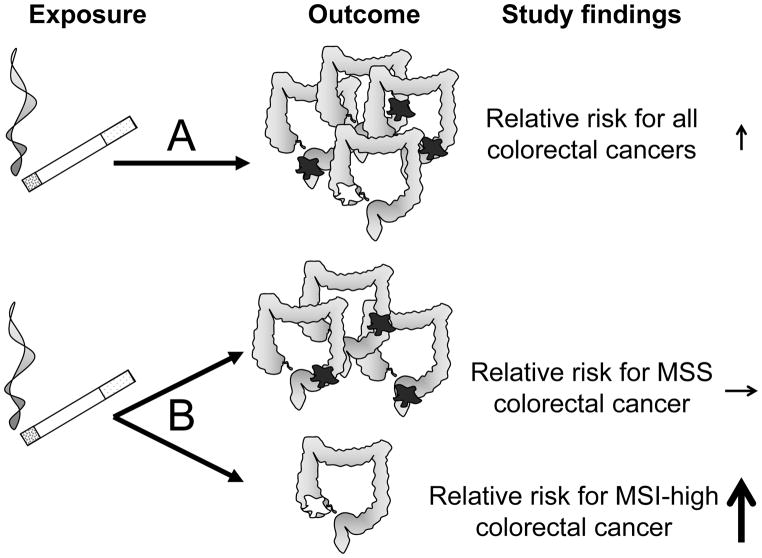

Figure 1.

A. A conventional epidemiologic approach assesses the association between an exposure (smoking) and disease occurrence as a single outcome (colorectal cancer). In this example, colorectal cancer is heterogeneous. Using a binary biomarker, MSI status, colorectal cancer comprises a majority of microsatellite stable tumors (MSS, dark fill on diagram) and a minority of tumors with high levels of microsatellite instability (MSI-High, white fill on diagram). A weak or modest association is observed between smoking and overall colorectal cancer risk. B. An MPE approach assesses associations between an exposure and molecularly-defined tumor subtypes. Here, the association between smoking and microsatellite stable tumor risk is null, whereas the magnitude of risk for MSI-H tumors is much greater than that for colorectal cancers overall.

MPE constitutes a logical strategy for post-genome-wide association study (GWAS) research (“GWAS-MPE approach” (5)), in which a candidate susceptibility variant may be linked to a specific disease subtype (40–42). Interaction analyses between exposures and tumor biomarkers are relatively understudied areas in MPE research, but can demonstrate the capacity of a biomarker to predict response or resistance to lifestyle, dietary or pharmacological interventions (4, 12, 13, 39, 43, 44).

Through an appreciation of disease heterogeneity and analyses of molecular alterations that accrue during carcinogenesis, MPE can provide new insights into the mechanisms through which exposures influence tumorigenic processes in the colorectum.

The colorectum as a resource for MPE research

As a result of the widespread application of colonoscopy in symptomatic investigation and screening, the colorectum has become an unparalleled resource for the study of neoplastic initiation and progression. In many other organs, access to premalignant lesions can be difficult, especially in the epidemiologic research setting (45). The colorectum represents an organ where both cancer tissue and premalignant tissue are readily accessible for molecular analyses, and can provide a model for research on neoplastic evolution in other organs. The colorectum is by far the most microorganism-rich organ in the human body, and colonic luminal contents are believed to play an important role in carcinogenesis (46, 47). Furthermore, as a contiguous hollow organ, and extension of the external environment, the influence of exposure to dietary, microbial, and metabolic constituents of the gut contents can be studied in relation to host factors, including anatomic subsite. These unique features of the colorectum, and neoplasms arising within it, provide substantial opportunities for research; however, MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions also poses important challenges.

The challenge of the unique tumor principle

In the MPE paradigm, genomic and epigenomic variants interact with non-genetic exposures, including dietary, lifestyle, environmental, and hormonal influences, to determine disease occurrence and progression differently in each patient, through changes in cellular and extracellular interactomes (48). Since the resulting changes in the tissue microenvironment in one individual will never be exactly the same as those in another, a specific disease process in a given individual can be considered unique. This concept is embodied in “the unique disease principle” (10) [or “the unique tumor principle” (49, 50)]. The unique tumor principle gains support from recent genomic and epigenomic projects demonstrating enormous tumor heterogeneity in several cancer types (51–53), from differential effects of diverse somatic aberrations (54, 55), and from the influence of host factors on tumor behavior (2, 43, 56, 57).

Epidemiology is based on the fundamental premise that we can predict disease occurrence and evolution by inference from other cases of what is nominally the same disease. The unique tumor principle therefore poses significant challenges. Nonetheless, the seemingly insurmountable problem of disease heterogeneity can be, at least partly, overcome by molecular tools capable of classifying cases into disease subtypes, which share molecular mechanisms and biologic phenotypes (58–68). Through molecular classification, we can subtype tumors to predict their evolution and response to interventions with greater accuracy.

Molecular classification of colorectal cancer

Commonly used molecular classifiers in colorectal cancer include mutations in KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA (69–75), and global molecular features such as microsatellite instability (MSI) (76–78), the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) (15, 16, 79–89), chromosomal instability (CIN) (90) and LINE-1 methylation level (10, 91–93). CIMP status may be divided into CIMP-high, CIMP-low and CIMP-negative (80, 94–99). LINE-1 methylation level can be a continuous classifier (100–102). These tumor molecular features have been widely investigated in relation to exposures (including diet, smoking, aspirin use, body mass index, physical activity, screening behavior, family history, and heritable genetic variants), immune reaction, colorectal cancer incidence, and outcomes (5, 12, 13, 103, 104).

Pathologic and molecular classification of colorectal premalignant lesions

Phenotypic heterogeneity has long been recognized in colorectal premalignant lesions. Historically, we have used lesion size and histopathological classification in an attempt to better predict malignant potential. Well-established pathologic entities include, tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, villous adenoma, hyperplastic polyp, sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) / sessile serrated polyp (SSP), and traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) (Figure 2). In addition, some hamartomatous polyps are considered to be premalignant lesions (105). The terms SSA and SSP can be used interchangeably, and there is no guideline to enforce one terminology over the other (21). In addition to molecular associations of well-established histopathological subtypes, gross morphology of polyps has been associated with tumor molecular features (106).

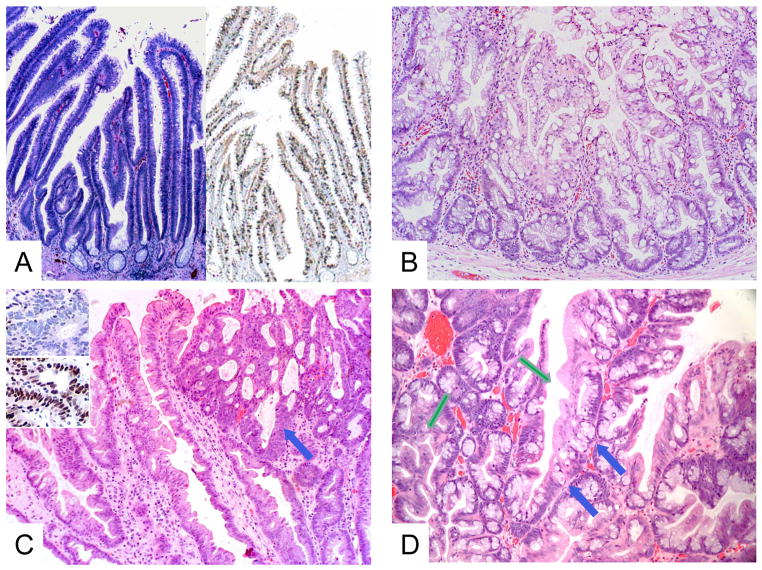

Figure 2. Histopathologic features of selected colorectal premalignant lesions.

A. KRAS-mutated villous adenoma [hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), original magnification x40] (left). Immunohistochemistry for MKI67 (Ki-67) shows brown nuclei indicating proliferative activity extending from crypts to villous tips (original magnification x40) (right). B. BRAF-mutated sessile serrated adenoma / sessile serrated polyp (SSA / SSP) showing characteristic irregular shapes of basal crypts (H&E, original magnification x100). C. BRAF-mutated SSA / SSP with cytological dysplasia (blue arrow) (H&E, original magnification x100). Insets show immunohistochemistry analysis with loss of MLH1 expression (top) and preservation of MSH2 expression (below) (original magnification x200). D. KRAS-mutated traditional serrated adenoma showing a tubulovillous architecture, serrated eosinophilic atypia (green arrow) and characteristic ectopic crypt formation (blue arrows) (H&E, original magnification, x100).

The conventional adenoma-carcinoma sequence encompasses three related histological entities, tubular, tubulovillous and villous adenomas, which exhibit multiple molecular pathway variations and account for the majority of colorectal cancers. In this sequence, APC mutation is a common early event (1); the ensuing disruption of WNT signaling results in a transformed clone of colonocytes that exhibits a dysplastic phenotype and may grow to form a tubular adenoma. In its earliest stage, represented by one or a small number of tubule-shaped crypts, the adenoma is termed an aberrant crypt focus or microadenoma. KRAS mutation is found in up to 50% of large (>1.0 cm) adenomas, and frequently associated with alteration of the polyp architecture from tubular to tubulovillous or villous (107–109).

By definition, all adenomas of this conventional sequence show at least low-grade dysplasia – the adenomatous phenotype. Only a small proportion progress to the next level, high grade dysplasia (HGD); this is defined by nuclear atypia and architectural disorder of the component glands, leading to cribriform structures. HGD is associated with larger size, villous morphology (110), TP53 mutation (111), and deletion of a region of chromosome 18q (111). Chromosomal instability (CIN) can be demonstrated in late precursor adenomas (112), and can be morphologically apparent as anaplasia and abnormal mitoses as HGD evolves. Potential causes of CIN may include APC, TP53 and FBXW7 mutations (113), AURKA overexpression (114, 115), JC virus (116, 117), and loss of PIGN, MEX3C and ZNF516 (109).

The serrated pathway is an alternative cancer progression sequence that accounts for the development of a minority of colorectal adenocarcinomas (21, 118). It comprises a series of polyps that have glands or crypts with a characteristic saw-toothed (serrated) outline, giving the pathway its histological signature and name. The serrated lesions commonly have BRAF or KRAS mutation. As a result of BRAF or KRAS mutation, adaptive changes, termed senescence (119), occur in the crypt cells, which are designed to forestall transformation (120). Early lesional crypts containing senescent cells are enlarged to accommodate colonocytes that have normal-appearing nuclei but increased cytoplasmic volume and reduced tendency to slough into the lumen. Those abnormal crypts with BRAF mutation commonly show marked serration of the crypts, and the cytoplasm of the cells is filled with small mucin vacuoles (microvesicular). The KRAS-mutated variant tends to show less prominent serration but marked tufting of the surface, and increased numbers of large goblet cells (121). Both variants are precursors of hyperplastic polyps that show these respective phenotypes, “microvesicular hyperplastic polyp” and “goblet cell hyperplastic polyp” (122). Hyperplastic polyps are small (usually less than 5 mm) sessile or flat polyps. These polyps arise predominantly in the distal colorectum, where they are felt to have limited malignant potential, as reflected by current surveillance guidelines (123). Serrated polyps with disordered growth represent an atypical hyperplastic polyp variant called sessile serrated adenoma or sessile serrated polyp, “SSA / SSP” (122). SSAs / SSPs can progress to develop dysplasia (Figure 2), and ultimately evolve into carcinoma (21). The progression from SSA / SSP to SSA / SSP with dysplasia may be associated with increasing promoter methylation of genes, including MLH1, CDX2, and TLR2 (124). The origins of SSAs / SSPs remain uncertain. It is not currently known whether these polyps develop from a single precursor lesion, or arise de novo. In common with microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, SSAs / SSPs are frequently characterized by mutated BRAF. It has therefore been suggested that microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, SSAs / SSPs, and SSAs / SSPs with dysplasia represent parts of a biologic spectrum, and this is supported by an apparent continuum of histological and DNA methylation changes (124–126). The endpoint carcinomas of the BRAF-mutated serrated pathway tend to arise in proximal colon and show CIMP-high and MSI-high due to MLH1 methylation, which leads to numerous somatic mutations (127). were previously thought to play no role in cancer evolution, but there is now compelling evidence that some of these lesions, particularly BRAF-mutated hyperplastic polyps in the proximal colon, are susceptible to further molecular changes, including epigenetic inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (128).

End-point KRAS-mutated serrated pathway carcinomas tend to occur distally, and show mismatch repair proficiency (or microsatellite stability) and CIMP-low, sometimes in association with MGMT epigenetic inactivation (129, 130). However, it is likely that not all CIMP-low cancers arise through the serrated pathway. One of the precursors of these carcinomas is considered to be Traditional Serrated Adenoma (TSA), a serrated polyp characterized by exophytic tubulovillous growth and distal location in the colorectum (21). KRAS-mutated Goblet Cell Hyperplastic Polyp may be a precursor of TSA (131). TSA may have heterogeneous pathogenesis; some TSA lesions harbor BRAF mutation, or wild-type BRAF and KRAS (21).

MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions

A typical study design for MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions, where an exposure of interest can be examined in relation to molecular subtypes of colorectal neoplasia, is illustrated in Figure 1. Compared to studies on colorectal cancer (4, 5), data on MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions remain relatively sparse (30, 132–137).

The definitive study design for investigating the initiation and progression of colorectal premalignant lesions would be to study the molecular and biologic evolution of the lesions in situ, in conjunction with comprehensive data on host exposures. Unfortunately, ethical considerations dictate that this study will never be performed in humans. We therefore require methods that can establish causal relationships between exposures (e.g., dietary, microbiologic, and host genetic factors) and specific tumor subtypes, while piecing together the biology of colorectal tumorigenesis from snapshots of the disease at different stages in its natural history.

MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions, in synergism with MPE of colorectal cancer, can fulfill this role. By way of example, if smoking is shown to be associated with premalignant lesions displaying CIMP-high (or BRAF mutation), it can provide additional evidence for a causal association between smoking and CIMP-high (or MSI-high/BRAF-mutated) colorectal cancer (138–142). An MPE approach can also provide clues to the timing of the carcinogenic effect of a given exposure. Considering the above example, if smoking is associated with an increased risk of premalignant lesions with CIMP-high or BRAF mutation, it can provide evidence for an effect of smoking on specific molecular events at an early phase in carcinogenesis. In contrast, if smoking is associated with CIMP-high or BRAF-mutated colorectal cancer, but not with the risk of premalignant lesions demonstrating these features, it would suggest that smoking facilitates the later progression, rather than initiation, of certain premalignant lesions via specific pathways.

Certain caveats are associated with MPE research on colorectal premalignant lesions. One major issue is case ascertainment. Although colorectal cancers may remain asymptomatic over lengthy periods of time, they usually declare themselves eventually, for example, when they bleed, become large enough to obstruct the lumen, or cause systemic symptoms through metastases. Therefore, in population-based studies, ascertainment of colorectal cancer cases is considered reasonably good; most individuals with colorectal cancer seek medical attention at some point.

In contrast, ascertainment of colorectal premalignant lesions (some of which may never progress to cancer) depends largely on endoscopic screening. In addition to the shift in clinical practice from screening sigmoidoscopy to colonoscopy in the U.S., endoscopic and adjunctive screening technologies, as well as the quality of lower endoscopic examinations, have substantially improved over the past decade. Changing endoscopic practice is therefore a potential source of bias and confounding.

Tissue availability represents a further potential source of bias. The size and morphology of colorectal premalignant lesions varies enormously. Diminutive lesions may yield only tiny fragments of tissue, or may remain undetected, whereas larger specimens provide abundant material for analysis. Furthermore, the size of a premalignant lesion correlates with its malignant potential, as well as feasibility of tumor tissue analyses. With advances in molecular methodologies, smaller quantities of biologic material are required for downstream analyses. Indeed, single cell whole genome sequencing is feasible from fresh specimens (143). While fresh tissue yields optimal quality material for molecular analyses, the practicalities of collecting and storing fresh clinical tissue samples often prohibit its use on a large scale. Archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, along with their clinical and pathological annotation, represent an immensely valuable resource for MPE research, and most MPE studies to date utilize archival specimens from participants of prospective cohort studies (30, 132–137). Although FFPE tissues provides good preservation of microarchitechture for in situ analytic approaches, including immunohistochemical analyses, cross-linking and fragmentation of biomolecules by formalin fixation impacts on the quality of nucleic acid recovered (144). Nonetheless, FFPE tissues have been successfully used for genomic, eigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses (145). In addition, laser capture microdissection (LCM) has proved invaluable in addressing tissue and cellular heterogeneity in molecular analyses of FFPE tissues. LCM comes with its own specific challenges, including contamination and low tissue quantities (146). The minimum amount of tissue required for molecular analyses is determined by many factors, including tissue fixation, storage, and age, tissue cellularity, cell ploidy, neoplastic cell abundance, and frequency of the molecular target (e.g., mutation/allele frequency). As little as 10 ng of FFPE-derived DNA may be required for techniques such as comparative genomic hybridization and certain targeted next generation sequencing approaches (147, 148). Furthermore, multiplex transcriptional analyses can be performed in situ, at single cell level (149). In contrast to the use of fresh frozen specimens in molecular research, where informed consent by the donor is usually the rule, the use of archival FFPE tissues, obtained for diagnostic purposes, raises a variety of bioethical considerations, including consent, sample ownership and custodianship, generation of data on germline genetic variants, and confidentiality of personally identifiable information (150, 151).

The anatomic location and morphology of lesions can also influence the likelihood of their being detected endoscopically. The detection of SSAs, for example, is highly variable between endoscopists (152–154). Thus, serrated neoplastic lesions, particularly those in the proximal colon, may easily be missed at colonoscopy, and it is interesting that molecular markers of the serrated pathway are frequently observed post-colonoscopy cancers (155, 156).

Pathological heterogeneity also poses considerable challenges to the MPE of premalignant lesions. As discussed in the preceding section, colorectal premalignant lesions are inherently heterogenous in terms of biology, morphology, and clinical behavior. In addition, nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for premalignant lesions, especially serrated lesions, has changed considerably over time, and may result in inter observer variation among pathologists (21, 152). Thus, a cross comparison of MPE studies on premalignant lesions is challenging. Distinct polyp types likely reflect different etiologies, and histopathological classification can serve as a surrogate in MPE-type analyses (157). Thus, the expertise for accurate pathological classification of premalignant lesions is essential to epidemiologic research.

Colorectal continuum

The colorectum has traditionally been regarded as a single organ, or, as colon and rectum. However, it has long been recognized that clinical and pathological differences exist between proximal and distal colon cancers, and a number of influential review articles have expounded a dichotomous concept of proximal vs. distal colorectum (158–160). Numerous clinical, pathological, and epidemiologic investigations have adopted this model, and differences in key molecular features between proximal and distal colonic tumors are well described (15, 16, 59, 84, 131).

Recently, Yamauchi et al. (54) broke with the prevailing two-colon model and examined molecular features of cancers occurring in 9 colorectal subsites. This study demonstrated that the frequencies of CIMP-high, MSI-high, and BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer increase gradually from rectum to ascending colon, challenging the notion of an acute transition at the splenic flexure (131). Independent studies have confirmed similar distributions in molecular features of colorectal cancers (34, 161–163). Furthermore, in synchronous colorectal cancers, molecular similarities are proportional to the physical proximity of the two cancers (164). A “continuum” hypothesis has therefore been proposed (165), which embodies the role of luminal contents, microbiota, and host responses in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. In support of the continuum model of gut biogeography, the colorectal microbiota, and lymphocytic and macrophage infiltrates appear to transition gradually along colorectal subsites (54, 56, 165, 166).

If we continue to use a dichotomous colorectal research model, we will predictably generate data that support the existence of such a model, provided markers of interest vary to some extent along the proximal-distal axis of the colorectum. Investigations on colorectal tumors should attempt to couple molecular classifiers with detailed subsite location in order to address potential heterogeneity by anatomic location.

Implications in cancer prevention

MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions can provide scientific evidence for cancer etiologies and enable us to develop and optimize cancer prevention strategies. First, by providing additional evidence for causality, MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions can help establish colorectal neoplasia risk factors, some of which may be modifiable.

Second, MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions can provide additional evidence for a mechanistic link between a risk factor and a particular carcinogenic pathway, characterized by a specific molecular alteration (such as MSI). Using MSI as an example, if we are ultimately able to identify those individuals with increased susceptibility to the development of cancers demonstrating MSI, we can recommend avoidance of the associated risk factor as a primary preventive measure.

Third, in analyses using recurrent premalignant lesions or metachronous cancer as endpoints, we can assess for interactive effects between tumor molecular markers and exposures, on the risk of developing subsequent neoplasia. If an interaction can be identified between a tumor molecular feature and an exposure (which may be a modifiable component of diet, lifestyle, or pharmacologic regimen), the molecular feature may serve as a predictive biomarker of response to intervention, warranting further assessment by clinical trials.

Conclusions

Molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE) has emerged as an integrative field that addresses molecular heterogeneity of diseases as well as disease distribution and occurrence in large human populations (4, 5). MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions can provide unique opportunities to examine the influence of an exposure on a specific carcinogenic process, and can be synergistic with the MPE of colorectal cancer. The recent emergence of the colorectal continuum hypothesis (54, 165) has added further complexity to the role of gut biogeography in cancer predisposition, and pathological and epidemiologic studies of premalignant lesions must strive to examine detailed colorectal subsites.

Considering future directions in MPE research, the rapidly-developing omics disciplines, and other emerging technologies (such as endomicroscopy, in vivo pathology, interactome, and molecular network analyses) can be applied to tissue repository resources in existing population-based cohort studies, which are unparalleled resources in terms of their large amassed quantities of exposure data. This represents a very cost-effective approach to advancing integrative MPE science and improving the health of human populations (19, 50, 167). Ultimately, as molecular pathological testing becomes routine in clinical practice, molecular classification data should be entered and accumulate within population disease registries throughout the world. This will facilitate the adoption of MPE research into standard epidemiologic practice. Since epidemiology ultimately attempts to advance our understanding of human disease, epidemiology in this 21st century must take into account advances in the molecular biology and pathophysiology of disease processes. One of the most profound challenges in MPE is the paucity of integrative expertise (in molecular pathology and epidemiology), and future educational reform, involving academic institutions that deliver teaching in medicine and public health, will be required to tackle this problem (168–170).

There are caveats associated with the MPE of premalignant lesions, especially with regard to case ascertainment, and we need to be aware of these potential sources of bias. Nonetheless, by careful study design and analyses, MPE can promote unprecedented discoveries that can contribute to better understanding of the development and progression colorectal neoplasia. Ultimately, MPE of colorectal premalignant lesions can help us achieve our goals of personalized medicine and effectively targeted public health interventions, leading to reductions in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

What is current knowledge?

Molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE) represents an integrative research paradigm.

MPE can 1) link a risk factor to specific molecular alterations, 2) refine a risk estimate for a specific molecular subtype of disease, 3) support a causal relationship, and 4) help to identify a potential tumor biomarker for clinical use.

MPE has been applied to colorectal cancer research.

Only a limited number of studies have conducted MPE research to examine colorectal premalignant lesions.

What is new?

By bridging the gap between normal tissue and malignancy, colorectal premalignant lesions are a unique resource for MPE research

MPE of premalignant lesions can help elucidate etiologies, mechanisms and heterogeneity of disease evolution

Opportunities in MPE of premalignant lesions are accompanied by challenges and caveats

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by grants from USA National Institute of Health (NIH) [R01 CA137178 (to ATC), P50 CA127003 (to CSF), R01 CA151993 (to SO), P01 CA87969 (to SE Hankinson)]. PL is a Scottish Government Clinical Academic Fellow. ATC is a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Funding agencies did not have any role in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, or the writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- AURKA

aurora kinase A

- BRAF

v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B

- CIMP

CpG island methylator phenotype

- CDX 2

caudal type homeobox 2

- CIN

chromosomal instability

- FBXW7

F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase

- FFPE

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- HGD

high-grade dysplasia

- KRAS

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- LINE-1

long interspersed nucleotide element-1

- MEX3C

mex-3 RNA binding family member C

- MGMT

O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

- MLH1

mutL homolog

- MPE

molecular pathological epidemiology

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- PIGN

phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class N

- PIK3CA

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha

- SSA

sessile serrated adenoma

- SSP

sessile serrated polyp

- TLR2

toll-like receptor 2

- TP53

tumor protein p53

- TSA

traditional serrated adenoma

- WNT

member of wingless-type mouse mammary tumor virus integration site protein family

- ZNF516

zinc finger protein 516

Footnotes

Use of Official Symbols for Genes and Gene Products: All symbols for genes and gene products used (APC, AURKA, BRAF, CDX2, FBXW7, KRAS, MEX3C, MGMT, MLH1, PIGN, PIK3CA, TLR2, TP53, WNT, and ZNF516) are approved by the HUGO (Human Genome Organisation), and described at www.genenames.org. Gene names are italicized and gene product names are non-italicized.

Guarantor of the article: SO

Specific author contributions: The idea for the article was conceived by SO. PL, ATC, MO, and SO drafted the manuscript. EG, RN, KW, and CSF critically reviewed the draft manuscript and provided material and suggestions for improvement. All authors reviewed and approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Potential competing interests: ATC was a consultant of Bayer Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer Inc. This work was not funded by Bayer Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, or Pfizer Inc. No other competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Lao VV, Grady WM. Epigenetics and colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:686–700. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, et al. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galon J, Franck P, Marincola FM, et al. Cancer classification using the Immunoscore: a worldwide task force. J Transl Med. 2012;10:205. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogino S, Stampfer M. Lifestyle factors and microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer: The evolving field of molecular pathological epidemiology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:365–367. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogino S, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, et al. Molecular pathological epidemiology of colorectal neoplasia: an emerging transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary field. Gut. 2011;60:397–411. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes LA, Simons CC, van den Brandt PA, et al. Body size, physical activity and risk of colorectal cancer with or without the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) PLoS One. 2011;6:e18571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spitz MR, Caporaso NE, Sellers TA. Integrative cancer epidemiology--the next generation. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1087–90. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koshiol J, Lin SW. Can Tissue-Based Immune Markers be Used for Studying the Natural History of Cancer? Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amirian ES, Petrosino JF, Ajami NJ, et al. Potential role of gastrointestinal microbiota composition in prostate cancer risk. Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogino S, Lochhead P, Chan AT, et al. Molecular pathological epidemiology of epigenetics: Emerging integrative science to analyze environment, host, and disease. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:465–484. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogino S, Lochhead P, Giovannucci E, et al. Discovery of colorectal cancer PIK3CA mutation as potential predictive biomarker: power and promise of molecular pathological epidemiology. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.244. in press (published online) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation status, and colorectal cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1596–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishihara R, Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, et al. Aspirin use and risk of colorectal cancer according to BRAF mutation status. JAMA. 2013;309:2563–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Imamura Y, et al. Physical Activity, Tumor PTGS2 Expression, and Survival in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2013;22:1142–1152. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtin K, Slattery ML, Samowitz WS. CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer: past, present and future. Pathology Research International. 2011;2011:902674. doi: 10.4061/2011/902674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes LA, Khalid-de Bakker CA, Smits KM, et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer: Progress and problems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1825:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwagami S, Baba Y, Watanabe M, et al. Pyrosequencing Assay to Measure LINE-1 Methylation Level in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2726–2732. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limburg PJ, Limsui D, Vierkant RA, et al. Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Relation to Somatic KRAS Mutation Status among Older Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:681–684. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes LA, Williamson EJ, van Engeland M, et al. Body size and risk for colorectal cancers showing BRAF mutation or microsatellite instability: a pooled analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1060–1072. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ku CS, Cooper DN, Wu M, et al. Gene discovery in familial cancer syndromes by exome sequencing: prospects for the elucidation of familial colorectal cancer type X. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1055–1068. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1315–1329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fini L, Grizzi F, Laghi L. Adaptive and Innate Immunity, Non Clonal Players in Colorectal Cancer Progression. In: Ettarh R, editor. Colorectal Cancer Biology - From Genes to Tumor. InTech; 2012. pp. 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gay LJ, Mitrou PN, Keen J, et al. Dietary, lifestyle and clinico-pathological factors associated with APC mutations and promoter methylation in colorectal cancers from the EPIC-Norfolk Study. J Pathol. 2012;228:405–415. doi: 10.1002/path.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chia WK, Ali R, Toh HC. Aspirin as adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer-reinterpreting paradigms. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:561–570. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dogan S, Shen R, Ang DC, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS Mutations in 3026 Lung Adenocarcinomas: Higher Susceptibility of Women to Smoking-related KRAS-mutant Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6169–6177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanmuganathan R, Nazeema Banu B, Amirthalingam L, et al. Conventional and Nanotechniques for DNA Methylation Profiling. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosty C, Young JP, Walsh MD, et al. Colorectal carcinomas with KRAS mutation are associated with distinctive morphological and molecular features. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:825–834. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weijenberg MP, Hughes LA, Bours MJ, et al. The mTOR Pathway and the Role of Energy Balance Throughout Life in Colorectal Cancer Etiology and Prognosis: Unravelling Mechanisms Through a Multidimensional Molecular Epidemiologic Approach. Curr Nutr Rep. 2013;2:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s13668-012-0038-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchanan DD, Win AK, Walsh MD, et al. Family History of Colorectal Cancer in BRAF p.V600E mutated Colorectal Cancer Cases. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:917–926. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Potter JD, et al. Genomic aberrations occuring in subsets of serrated colorectal lesions but not conventional adenomas. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2863–2872. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarez MC, Santos JC, Maniezzo N, et al. MGMT and MLH1 methylation in Helicobacter pylori-infected children and adults. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3043–51. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagland HR, Berg M, Jolma IW, et al. Molecular Pathways and Cellular Metabolism in Colorectal Cancer. Dig Surg. 2013;30:12–25. doi: 10.1159/000347166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbenhardt C, Poole EM, Kulmacz RJ, et al. Phospholipase A2G1B polymorphisms and risk of colorectal neoplasia. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2013;4:140–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bae JM, Kim JH, Cho NY, et al. Prognostic implication of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancers depends on tumour location. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1004–1012. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikramuddin S, Livingston EH. New Insights on Bariatric Surgery Outcomes. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310:2401–2402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Y, Yang SR, Wang PP, et al. Influence of pre-diagnostic cigarette smoking on colorectal cancer survival: overall and by tumour molecular phenotype. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1359–66. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffmeister M, Blaker H, Kloor M, et al. Body Mass Index and Microsatellite Instability in Colorectal Cancer: A Population-based Study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2013;22:2303–2311. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobs RJ, Voorneveld PW, Kodach LL, et al. Cholesterol metabolism and colorectal cancers. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2012;12:690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Association of CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) alterations, body mass index, and physical activity with survival in patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:1685–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gruber SB, Moreno V, Rozek LS, et al. Genetic variation in 8q24 associated with risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1143–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.7.4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slattery ML, Herrick J, Curtin K, et al. Increased Risk of Colon Cancer Associated with a Genetic Polymorphism of SMAD7. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1479–1485. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia-Albeniz X, Nan H, Valeri L, et al. Phenotypic and tumor molecular characterization of colorectal cancer in relation to a susceptibility SMAD7 variant associated with survival. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:292–298. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogino S, Galon J, Fuchs CS, et al. Cancer immunology-analysis of host and tumor factors for personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:711–719. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogino S, Nosho K, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Cohort study of fatty acid synthase expression and patient survival in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5713–5720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caporaso NE. Why precursors matter. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:518–20. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, et al. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1907–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kostic AD, Chun EY, Robertson L, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Potentiates Intestinal Tumorigenesis and Modulates the Tumor-Immune Microenvironment. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013;14:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vidal M, Cusick ME, Barabasi AL. Interactome networks and human disease. Cell. 2011;144:986–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. How many molecular subtypes? Implications of the unique tumor principle in personalized medicine. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12:621–628. doi: 10.1586/erm.12.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogino S, Giovannucci E. Commentary: Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer microsatellite instability - molecular pathological epidemiology science, based on unique tumour principle. In J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1072–1074. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammerman PS, Hayes DN, Wilkerson MD, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–25. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imamura Y, Morikawa T, Liao X, et al. Specific Mutations in KRAS Codons 12 and 13, and Patient Prognosis in 1075 BRAF-wild-type Colorectal Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4753–4763. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen CC, Er TK, Liu YY, et al. Computational Analysis of KRAS Mutations: Implications for Different Effects on the KRAS p.G12D and p. G13D Mutations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, et al. The distribution of macrophages with a m1 or m2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Galon J, Mlecnik B, Bindea G, et al. Towards the introduction of the Immunoscore in the classification of malignant tumors. J Pathol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/path.4287. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Febbo PG, Ladanyi M, Aldape KD, et al. NCCN Task Force report: Evaluating the clinical utility of tumor markers in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9 (Suppl 5):S1–32. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0137. quiz S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogino S, Goel A. Molecular classification and correlates in colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:13–27. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zlobec I, Bihl MP, Schwarb H, et al. Clinicopathological and protein characterization of BRAF- and K-RAS-mutated colorectal cancer and implications for prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:367–380. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guastadisegni C, Colafranceschi M, Ottini L, et al. Microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and response to therapy: a meta-analysis of colorectal cancer survival data. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2788–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myers MB, Wang Y, McKim KL, et al. Hotspot oncomutations: implications for personalized cancer treatment. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12:603–20. doi: 10.1586/erm.12.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gavin P, Colangelo LH, Fumagalli D, et al. Mutation Profiling and Microsatellite Instability in Stage II and III Colon Cancer: An Assessment of their Prognostic and Oxaliplatin Predictive Value. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6531–6541. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Curtin K, Samowitz WS, Ulrich CM, et al. Nutrients in Folate-Mediated, One-Carbon Metabolism and the Risk of Rectal Tumors in Men and Women. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:357–366. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.535965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Q, Peng Z, Huang C, et al. The Critical Role of Dysregulated FOXM1-PLAUR Signaling in Human Colon Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:62–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeon JY, Meyerhardt JA. Energy in and energy out: what matters for survivors of colorectal cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:7–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Belt EJ, Brosens RP, Delis-van Diemen PM, et al. Cell Cycle Proteins Predict Recurrence in Stage II and III Colon Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:S682–692. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Waldron L, Ogino S, Hoshida Y, et al. Expression profiling of archival tissues for long-term health studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6136–6146. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut. 2009;58:90–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.155473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zlobec I, Bihl M, Foerster A, et al. Comprehensive analysis of CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP)-high, -low, and -negative colorectal cancers based on protein marker expression and molecular features. J Pathol. 2011;225:336–343. doi: 10.1002/path.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu C, Bekaii-Saab T. CpG island methylation, microsatellite instability, and BRAF mutations and their clinical application in the treatment of colon cancer. Chemother Res Prac. 2012;2012:359041. doi: 10.1155/2012/359041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liao X, Morikawa T, Lochhead P, et al. Prognostic Role of PIK3CA Mutation in Colorectal Cancer: Cohort Study and Literature Review. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2257–2268. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, et al. KRAS-mutation status in relation to colorectal cancer survival: the joint impact of correlated tumour markers. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1757–1764. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sethi S, Ali S, Phillip PA, et al. Clinical advances in molecular biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:14771–14784. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wangefjord S, Sundstrom M, Zendehrokh N, et al. Sex differences in the prognostic significance of KRAS codons 12 and 13, and BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer: a cohort study. Biol Sex Differ. 2013;4:17. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Funkhouser WK, Lubin IM, Monzon FA, et al. Relevance, pathogenesis, and testing algorithm for mismatch repair-defective colorectal carcinomas: A report of the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goel A, Boland CR. Epigenetics of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1442–1460. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Colussi D, Brandi G, Bazzoli F, et al. Molecular Pathways Involved in Colorectal Cancer: Implications for Disease Behavior and Prevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:16365–16385. doi: 10.3390/ijms140816365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8681–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hinoue T, Weisenberger DJ, Lange CP, et al. Genome-scale analysis of aberrant DNA methylation in colorectal cancer. Genome Res. 2012;22:271–282. doi: 10.1101/gr.117523.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dahlin AM, Henriksson ML, Van Guelpen B, et al. Colorectal cancer prognosis depends on T-cell infiltration and molecular characteristics of the tumor. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:671–682. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zlobec I, Bihl MP, Foerster A, et al. The impact of CpG island methylator phenotype and microsatellite instability on tumour budding in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2012;61:777–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zlobec I, Bihl MP, Foerster A, et al. Stratification and Prognostic Relevance of Jass’s Molecular Classification of Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:7. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Yamano HO, et al. Molecular Dissection of Premalignant Colorectal Lesions Reveals Early Onset of the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1847–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang Q, Dong Y, Wu W, et al. Detection and differential diagnosis of colon cancer by a cumulative analysis of promoter methylation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1206. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beggs AD, Jones A, El-Bahwary M, et al. Whole-genome methylation analysis of benign and malignant colorectal tumours. J Pathol. 2013;229:697–704. doi: 10.1002/path.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Karpinski P, Walter M, Szmida E, et al. Intermediate- and low-methylation epigenotypes do not correspond to CpG island methylator phenotype (low and -zero) in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:201–208. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bardhan K, Liu K. Epigenetics and colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Cancers. 2013;5:676–713. doi: 10.3390/cancers5020676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dawson H, Galvan JA, Helbling M, et al. Possible role of Cdx2 in the serrated pathway of colorectal cancer characterized by BRAF mutation, high-level CpG Island methylator phenotype and mismatch repair-deficiency. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2342–51. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mouradov D, Domingo E, Gibbs P, et al. Survival in stage II/III colorectal cancer is independently predicted by chromosomal and microsatellite instability, but not by specific driver mutations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kitkumthorn N, Mutirangura A. Long interspersed nuclear element-1 hypomethylation in cancer: biology and clinical applications. Clin Epigenet. 2012;2:315–330. doi: 10.1007/s13148-011-0032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ibrahim AE, Arends MJ, Silva AL, et al. Sequential DNA methylation changes are associated with DNMT3B overexpression in colorectal neoplastic progression. Gut. 2011;60:499–508. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sunami E, de Maat M, Vu A, et al. LINE-1 hypomethylation during primary colon cancer progression. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) in colorectal cancer: possible associations with male sex and KRAS mutations. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:582–588. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barault L, Charon-Barra C, Jooste V, et al. Hypermethylator phenotype in sporadic colon cancer: study on a population-based series of 582 cases. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8541–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim JH, Shin SH, Kwon HJ, et al. Prognostic implications of CpG island hypermethylator phenotype in colorectal cancers. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:485–494. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0857-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dahlin AM, Palmqvist R, Henriksson ML, et al. The Role of the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype in Colorectal Cancer Prognosis Depends on Microsatellite Instability Screening Status. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1845–1855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Donada M, Bonin S, Barbazza R, et al. Management of stage II colon cancer - the use of molecular biomarkers for adjuvant therapy decision. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Samadder NJ, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, et al. Associations Between Colorectal Cancer Molecular Markers and Pathways with Clinico-Pathologic Features in Older Women. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:348–356. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, et al. A cohort study of tumoral LINE-1 hypomethylation and prognosis in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1734–1738. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ahn JB, Chung WB, Maeda O, et al. DNA methylation predicts recurrence from resected stage III proximal colon cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1847–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Antelo M, Balaguer F, Shia J, et al. A High Degree of LINE-1 Hypomethylation Is a Unique Feature of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Palmqvist R, Wikberg ML, Ling A, et al. The association of immune cell infiltration and prognosis in colorectal cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Di Caro G, Marchesi F, Laghi L, et al. Immune cells: plastic players along colorectal cancer progression. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17:1088–95. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schreibman IR, Baker M, Amos C, et al. The hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: a clinical and molecular review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:476–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Voorham QJ, Rondagh EJ, Knol DL, et al. Tracking the Molecular Features of Nonpolypoid Colorectal Neoplasms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1042–1056. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Maltzman T, Knoll K, Martinez ME, et al. Ki-ras proto-oncogene mutations in sporadic colorectal adenomas: relationship to histologic and clinical characteristics. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:302–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Burrell RA, McClelland SE, Endesfelder D, et al. Replication stress links structural and numerical cancer chromosomal instability. Nature. 2013;494:492–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.O’Brien MJ, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, et al. The National Polyp Study. Patient and polyp characteristics associated with high-grade dysplasia in colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:371–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baker SJ, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, et al. p53 gene mutations occur in combination with 17p allelic deletions as late events in colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7717–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jones AM, Thirlwell C, Howarth KM, et al. Analysis of copy number changes suggests chromosomal instability in a minority of large colorectal adenomas. J Pathol. 2007;213:249–56. doi: 10.1002/path.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fodde R, Kuipers J, Rosenberg C, et al. Mutations in the APC tumour suppressor gene cause chromosomal instability. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:433–8. doi: 10.1038/35070129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nishida N, Nagasaka T, Kashiwagi K, et al. High Copy Amplification of the Aurora-A Gene is Associated with Chromosomal Instability Phenotype in Human Colorectal Cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:525–533. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.4.3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Baba Y, Nosho K, Shima K, et al. Aurora-A expression is independently associated with chromosomal instability in colorectal cancer. Neoplasia. 2009;11:418–25. doi: 10.1593/neo.09154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ricciardiello L, Baglioni M, Giovannini C, et al. Induction of chromosomal instability in colonic cells by the human polyomavirus JC virus. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7256–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nosho K, Shima K, Kure S, et al. JC virus T-antigen in colorectal cancer is associated with p53 expression and chromosomal instability, independent of CpG island methylator phenotype. Neoplasia. 2009;11:87–95. doi: 10.1593/neo.81188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rosty C, Hewett DG, Brown IS, et al. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: current understanding of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:287–302. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ, et al. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2463–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.1971610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wajapeyee N, Serra RW, Zhu X, et al. Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell. 2008;132:363–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rosenberg DW, Yang S, Pleau DC, et al. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS differentially distinguish serrated versus non-serrated hyperplastic aberrant crypt foci in humans. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3551–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC, et al. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:65–81. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dhir M, Yachida S, Van Neste L, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas and classical adenomas: an epigenetic perspective on premalignant neoplastic lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1889–98. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sweetser S, Smyrk TC, Sinicrope FA. Serrated colon polyps as precursors to colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:760–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.004. quiz e54–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, et al. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013;62:367–86. doi: 10.1111/his.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nosho K, Irahara N, Shima K, et al. Comprehensive biostatistical analysis of CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer using a large population-based sample. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL, et al. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut. 2004;53:1137–44. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Whitehall VL, Walsh MD, Young J, et al. Methylation of O-6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase characterizes a subset of colorectal cancer with low-level DNA microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 2001;61:827–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ogino S, kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, et al. Molecular correlates with MGMT promoter methylation and silencing support CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2007;56:1409–1416. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Huang CS, Farraye FA, Yang S, et al. The clinical significance of serrated polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:229–40. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.429. quiz 241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Martinez ME, Maltzman T, Marshall JR, et al. Risk factors for Ki-ras protooncogene mutation in sporadic colorectal adenomas. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5181–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wark PA, Van der Kuil W, Ploemacher J, et al. Diet, lifestyle and risk of K-ras mutation-positive and -negative colorectal adenomas. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:398–405. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Einspahr JG, Martinez ME, Jiang R, et al. Associations of Ki-ras proto-oncogene mutation and p53 gene overexpression in sporadic colorectal adenomas with demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1443–50. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.van den Donk M, van Engeland M, Pellis L, et al. Dietary folate intake in combination with MTHFR C677T genotype and promoter methylation of tumor suppressor and DNA repair genes in sporadic colorectal adenomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:327–33. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Martinez F, Fernandez-Martos C, Quintana MJ, et al. APC and KRAS mutations in distal colorectal polyps are related to smoking habits in men: results of a cross-sectional study. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:664–71. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0712-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Koestler DC, Li J, Baron JA, et al. Distinct patterns of DNA methylation in conventional adenomas involving the right and left colon. Mod Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Sweeney C, et al. Association of smoking, CpG island methylator phenotype, and V600E BRAF mutations in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1731–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Curtin K, Samowitz WS, Wolff RK, et al. Somatic alterations, metabolizing genes and smoking in rectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:158–64. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Limsui D, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, et al. Cigarette Smoking and Colorectal Cancer Risk by Molecularly Defined Subtypes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1012–1022. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Rozek LS, Herron CM, Greenson JK, et al. Smoking, gender, and ethnicity predict somatic BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:838–843. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, et al. A prospective study of duration of smoking cessation and colorectal cancer risk by epigenetics-related tumor classification. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:84–100. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Navin N, Kendall J, Troge J, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Frankel A. Formalin fixation in the ‘-omics’ era: a primer for the surgeon-scientist. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:395–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Klopfleisch R, Weiss AT, Gruber AD. Excavation of a buried treasure--DNA, mRNA, miRNA and protein analysis in formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissues. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:797–810. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Legres LG, Janin A, Masselon C, et al. Beyond laser microdissection technology: follow the yellow brick road for cancer research. Am J Cancer Res. 2014;4:1–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Johnson NA, Hamoudi RA, Ichimura K, et al. Application of array CGH on archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues including small numbers of microdissected cells. Lab Invest. 2006;86:968–78. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tsongalis GJ, Peterson JD, de Abreu FB, et al. Routine use of the Ion Torrent AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel for identification of clinically actionable somatic mutations. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Capodieci P, Donovan M, Buchinsky H, et al. Gene expression profiling in single cells within tissue. Nat Methods. 2005;2:663–5. doi: 10.1038/NMETH786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Dry S, Grody WW, Papagni P. Stuck between a scalpel and a rock, or molecular pathology and legal-ethical issues in use of tissues for clinical care and research: what must a pathologist know? Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:346–55. doi: 10.1309/AJCPS26UKHNYCEAV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.With CM, Evers DL, Mason JT. Regulatory and ethical issues on the utilization of FFPE tissues in research. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;724:1–21. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-055-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hetzel JT, Huang CS, Coukos JA, et al. Variation in the detection of serrated polyps in an average risk colorectal cancer screening cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2656–64. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Kahi CJ, Li X, Eckert GJ, et al. High colonoscopic prevalence of proximal colon serrated polyps in average-risk men and women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:515–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, Bossuyt PM, et al. Differences in proximal serrated polyp detection among endoscopists are associated with variability in withdrawal time. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:617–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095–105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Arain MA, Sawhney M, Sheikh S, et al. CIMP status of interval colon cancers: another piece to the puzzle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1189–95. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Burnett-Hartman AN, Passarelli MN, Adams SV, et al. Differences in epidemiologic risk factors for colorectal adenomas and serrated polyps by lesion severity and anatomical site. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:625–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Bufill JA. Colorectal cancer: evidence for distinct genetic categories based on proximal or distal tumor location. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:779–88. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-10-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Iacopetta B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int J Cancer. 2002;101:403–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Carethers JM. One colon lumen but two organs. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:411–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, et al. BRAF mutation status and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis according to patient and tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1792–1798. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Rosty C, Young JP, Walsh MD, et al. PIK3CA Activating Mutation in Colorectal Carcinoma: Associations with Molecular Features and Survival. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Phipps AI, Lindor NM, Jenkins MA, et al. Colon and Rectal Cancer Survival by Tumor Location and Microsatellite Instability: The Colon Cancer Family Registry. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:937–944. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828f9a57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Zauber P, Huang J, Sabbath-Solitare M, et al. Similarities of Molecular Genetic Changes in Synchronous and Metachronous Colorectal Cancers Are Limited and Related to the Cancers’ Proximities to Each Other. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:652–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, et al. Colorectal cancer: a tale of two sides or a continuum? Gut. 2012;61:794–797. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Li X, Leblanc J, Truong A, et al. A metaproteomic approach to study human-microbial ecosystems at the mucosal luminal interface. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Colditz GA. Ensuring long-term sustainability of existing cohorts remains the highest priority to inform cancer prevention and control. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:649–56. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9498-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Ogino S, King EE, Beck AH, et al. Interdisciplinary education to integrate pathology and epidemiology: towards molecular and population-level health science. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:659–667. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Kuller LH. Invited Commentary: The 21st century epidemiologist -- a need for different training? Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:668–671. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Ogino S, Beck AH, King EE, et al. Ogino et al. respond to “The 21st century epidemiologist”. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:672–674. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]