Abstract

Understanding the molecular pathogenesis of lung cancer is necessary to identify biomarkers/targets specific to individual airway molecular profiles and to identify options for targeted chemoprevention. Herein, we identify mechanisms by which loss of microRNA (miRNA)-125a-3p (miR-125a) contributes to the malignant potential of human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) harboring an activating point mutation of the K-ras proto-oncogene (HBEC K-ras). Among other miRNAs, we identified significant miR-125a loss in HBEC K-ras lines and determined that miR-125a is regulated by the PEA3 transcription factor. PEA3 is upregulated in HBEC K-ras cells, and genetic knockdown of PEA3 restores miR-125a expression. From a panel of inflammatory/angiogenic factors, we identified increased CXCL1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production by HBEC K-ras cells and determined that miR-125a overexpression significantly reduces K-ras-mediated production of these tumorigenic factors. miR-125a overexpression also abrogates increased proliferation of HBEC K-ras cells and suppresses anchorage-independent growth (AIG) of HBEC K-ras/P53 cells, the latter of which is CXCL1-dependent. Finally, pioglitazone increases levels of miR-125a in HBEC K-ras cells via PEA3 downregulation. In addition, pioglitazone and miR-125a overexpression elicit similar phenotypic responses, including suppression of both proliferation and VEGF production. Our findings implicate miR-125a loss in lung carcinogenesis and lay the groundwork for future studies to determine if miR-125a is a possible biomarker for lung carcinogenesis and/or a chemoprevention target. Moreover, our studies illustrate that pharmacologic augmentation of miR-125a in K-ras-mutated pulmonary epithelium effectively abrogates several deleterious downstream events associated with the mutation.

Keywords: miR-125a, pulmonary premalignancy, molecular markers, PEA3

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the U.S., accounting for more deaths than prostate, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancers combined (1). The high mortality rate is largely due to the late stage at which lung cancer is diagnosed, underscoring the need for identification of biomarkers for early lung cancer development and more effective lung cancer chemoprevention options (2). While early detection has been the focus of research efforts resulting in recent notable achievements (3), lung cancer chemoprevention has lagged behind (4). Despite extensive efforts, agents evaluated in the majority of lung cancer chemoprevention phase III clinical trials have been found to be ineffective or even harmful (5). Thus, current guidelines do not recommend agents for lung cancer chemoprevention (6). Major clinical breakthroughs in advanced stage lung cancer have been facilitated by the recent advent of patient selection based upon tumor mutational profiles that have fostered a personalized medicine approach for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (7). This paradigm shift has not yet fully reached clinical lung cancer chemoprevention; however, there is increasing recognition that the step-wise molecular alterations precipitating lung cancer development must be better defined to facilitate development of: 1) risk assessment targets, 2) biomarkers for patient selection, and 3) outcome prediction for specific agents (6, 8, 9).

MiRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that inhibit expression of specific genes at the post-transcriptional level by binding to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of their target mRNAs, causing suppression of translation or promotion of mRNA degradation (10). They have emerged as key regulators of proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, processes commonly altered in carcinogenesis (11). Indeed, a rapidly developing literature supports an important role for miRNA in the regulation of lung carcinogenesis and tumor progression (12, 13). Importantly, miRNAs are frequently dysregulated in cancer and have differential expression in tumors compared to normal tissues (14). Differences in miRNA expression patterns can also indicate prognosis. For example, expression of let-7a and let-7f miRNA is prognostic for survival of patients with lung cancer (15). Further, the stability of miRNAs renders them attractive candidates for robust, non-invasive biomarkers for the early detection of lung cancer. The following studies arose from our search for mutation-driven alterations in miRNAs that are potential biomarkers in the lung “at-risk” for the development of lung cancer.

MiR-125a-3p and miR-125a-5p are two mature isoforms of miR-125a, derived from the 3′ and 5′ ends of pre-miR-125a, respectively. MiR-125a is located at chromosome 19q13, a chromosomal region frequently deleted in human cancer. Several studies support the importance of miR-125a in various types of cancer. Overexpression of miR-125a reduces migration, invasion, and AIG of breast cancer cells, and a germline mutation of miR-125a is highly associated with breast cancer tumorigenesis (16, 17). In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues, expression of miR-125a is frequently downregulated compared with matched adjacent liver tissue, and lower expression of miR-125a inversely correlates with aggressiveness and poor prognosis of patients with HCC (18). Further, overexpression of miR-125a inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells both in vitro and in vivo (18). In patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma, a tobacco-related cancer, salivary levels of miR-125a are lower compared with healthy controls, suggesting its utility as a biomarker for oral cancer (19). Importantly, miR-125a is also downregulated in NSCLC tissues compared to corresponding adjacent normal lung tissue, and expression of miR-125a negatively correlates with pathological tumor stage and lymph node metastasis (20). In lung cancer cell lines, a gain-of-function of miR-125a inhibits cell migration, invasion, and proliferation, and induces apoptosis in vitro (20, 21). Conversely, miR-125a loss-of-function enhances lung cancer cell growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and migration. Despite this evidence supporting the importance of miR-125a in late stage cancer, its role in premalignancy, particularly pulmonary carcinogenesis, has yet to be defined.

To model the early pathogenesis of lung cancer, we utilized the in vitro HBEC model system (22, 23). These cells were immortalized in the absence of viral oncoproteins via ectopic expression of human telomerase (hTERT) and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4). In contrast to cancer cell lines with a mixed genetic background, HBECs are a unique in vitro model of lung carcinogenesis that allows evaluation of pathway intermediaries in isolation. These immortalized HBECs are partially progressed lung epithelial cells that can differentiate into mature airway cells in organotypic cultures, but do not have a fully transformed phenotype (i.e. do not form tumors in immunodeficient mice), making them a physiologically appropriate preclinical model of lung premalignancy.

Here, we report that loss of miR-125a-3p (hereafter referred to as miR-125a) expression contributes to the malignant potential of HBECs harboring an activating point-mutation of the K-ras proto-oncogene, one of the most clinically challenging genetic changes commonly found in current and former smokers. Compared to vector control, reduced expression of miR-125a in K-ras- and/or K-ras/P53-mutated HBECs was associated with increased levels of VEGF and CXCL1, increased proliferation, and enhanced AIG. Furthermore, we demonstrate pharmacologic augmentation of miR-125a expression can abrogate several of the deleterious downstream events associated with K-ras mutation. Taken together, our findings suggest that loss of miR-125a expression participates in the pathogenesis of pulmonary premalignancy.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

Immortalized HBEC lines (obtained from Dr. John D. Minna, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) were established by introducing CDK4 and hTERT into normal HBECs isolated from large airways of patients (22, 23). Three parental cell lines derived from three patients, HBEC3, HBEC7 and HBEC11, were used. These HBECs were subsequently manipulated to stably express the vector control (HBEC Vector) or an activating point-mutation of the K-ras proto-oncogene (K-rasV12; HBEC K-ras), alone or in combination with stable knockdown of the P53 tumor suppressor gene (HBEC K-ras/P53), as previously described (22); each was generated in the UCLA Vector Core. A restriction-fragment-length polymorphism analysis of K-ras cDNA validated that mutant K-rasV12 transcripts were predominately expressed in HBEC K-ras cells compared with the vector control. All cell lines were routinely tested for the presence of Mycoplasma using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza Walkersville). Cell lines were authenticated in the UCLA Genotyping and Sequencing Core utilizing Promega’s DNA IQ System and Powerplex 1.2 system. All cells were utilized within 10 passages of genotyping. HBECs were cultured in Keratinocyte Serum-Free Media (Life Technologies) supplemented with 30 μg/mL Bovine Pituitary Extract and 200 ng/mL recombinant Epidermal Growth Factor 1-53 (Life Technologies). Cell cultures were grown in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Pioglitazone (Enzo Life Sciences) was prepared in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mmol/L, and cells were treated at a final concentration of 10 μmol/L in supplement-free media. CXCL1 (PeproTech) was prepared in 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at a concentration of 10 ng/mL, and cells were treated at a final concentration of 10 pg/mL in complete media.

miRNA PCR arrays

Total RNA (including miRNA) was isolated from HBEC K-ras and Vector cell lines using the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Expression of 667 miRNAs was evaluated using the TaqMan™ Human miRNA Array v.2 (Life Technologies). Briefly, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using Megaplex Primer Pools A and B and the resulting cDNA for each sample was then loaded on two 384-well microfluidic array cards containing TaqMan™ primers and probes for miRNA and normalization controls followed by Real-Time PCR. The PCR data was normalized and analyzed with SDS v.2.3 software (Life Technologies) using the ΔΔCt method. To accurately compare miRNA expression across the study samples, the same Ct threshold was utilized for all samples. Wells with Ct values ≤35 were counted as negative.

Transient transfection of miR-125a and siRNA

Cells were plated in 6-well plates at 1.5 × 104 cells/well. For transient overexpression of miR-125a, HBEC3 Vector, K-ras, and K-ras/P53 cells were transfected with the miRVana™ hsa-miR-125a-3p mimic (Cat# 4464066, ID# MC12378) or Negative Control #1 (Cat# 4464058; both Life Technologies) at a final concentration of 10 nm, unless otherwise stated. For PEA3 knockdown, two different siRNA oligonucleotides specific for PEA3 were utilized: siRNA ID# s4816 (10 nmol/L) and siRNA ID# 115237 (50 nmol/L; both Life Technologies). HBEC3 K-ras cells were transfected with PEA3 siRNA or a non-targeting siRNA control. Transfections were carried out using the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Life Technologies) for 4 h before replacement with complete media.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit, and cDNA for mRNA or miRNA analysis was prepared using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit or the TaqMan™ miRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (both Life Technologies), respectively. Transcript levels of miR-125a and PEA3 were measured by qRT-PCR using the TaqMan™ Probe-based Gene Expression System (Life Technologies) in a MyiQ Cycler (Bio-Rad). Amplification was carried out for 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C. All samples were run in triplicate, and relative gene/miRNA expression levels were determined by normalizing their expression to RNU6B (mir-125a) or GUSB (PEA3). Expression data are presented as fold-change values relative to normalized expression levels in a reference sample using the following equation: RQ = 2-ΔΔCt.

Western blot analysis

HBEC Vector and K-ras cells were plated in 6-well plates at 1.5 × 104 cells/well. Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and total cell lysates were collected using a modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. For detection of PEA3, membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in TBS with 0.05% Tween 20 and probed overnight with a PEA3 monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution; Cat# sc-113; Santa Cruz). GAPDH was used as a loading control, and protein levels were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce Biotechnology). Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software (24).

Proliferation Assay

As an indication of cell viability and proliferation, cellular ATP levels were measured using the ATPlite 1step luminescence assay kit (Perkin Elmer). Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 1 × 103 cells/well. Six replicates for each condition were plated for each independent experiment. For miR-125a overexpression studies, HBEC3 Vector and K-ras cells were transfected with miR-125a mimic or negative control (10 nmol/L) 24 h prior to plating into 96-well plates. For pioglitazone studies, cells were treated with pioglitazone (10 μmol/L) or DMSO control diluted in 50% complete media + 50% supplement-free media. Treatment started following overnight attachment and continued for 48 h. ATP luminescence was assessed at 0 and 48 h; 48 h readings were normalized to the 0 h readings to control for plating differences.

Luminex-based multiplex assay

We performed a fluorescence-based cytokine screen using the Luminex-based multiplex system from Bio-Rad. HBEC Vector and K-ras cells were cultured and grown to 30-40% confluency, then washed twice with PBS before fresh medium was added. Cells were incubated for an additional 48 h, after which the supernatants were collected and centrifuged to remove contaminating cells. Lysates were prepared from the adherent cells, and the BCA assay was performed to determine protein concentration. A customized panel of 7 human cytokine/growth factors (Bio-Rad) was used, and all samples were run in triplicate. Results were normalized to protein concentration from the matched lysates and then expressed as fold-change over unselected cell cytokine secretion (post-normalization). We used ANOVA to compare cell populations for each analyte, and adjusted for multiple testing by computing the false-discovery rate using the q-value method implemented in R. Cytokines differentially produced by the cells were verified by ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

HBEC3 Vector, K-ras, or K-ras/P53 cells were plated in 6-well plates at 1.5 × 104 cells/well. Following overnight attachment, complete media was removed, and the cells were cultured in supplement-free media. After 48 h, supernatants were collected and protein levels of VEGF and CXCL1 were quantified using a DuoSet ELISA Development System (R&D Systems). For miR-125 overexpression studies, cells were transfected with miR-125a mimic or negative control (10 nmol/L) following overnight attachment. Supernatants were collected 48 h post-transfection and assayed as above. For pioglitazone studies, treatment with pioglitazone (10 μmol/L) or the DMSO control started following overnight attachment. Supernatants were collected 48 h after treatment initiation. Lysates were prepared from the adherent cells, and the BCA assay was performed to determine protein concentration. Results were normalized to protein concentration from the matched lysates.

AIG assay

We utilized a modified high-throughput cell transformation assay for evaluation of soft agar colony growth. Briefly, the cells are suspended in 0.4% agar and plated atop a thick layer of solidified 0.6% agar. HBEC Vector, K-ras, and K-ras/P53 cells were plated in 96-well plates at 1 × 104 cells/well. For miR-125a overexpression studies, HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells were transfected with miR-125a mimic or negative control (1 nmol/L) 24 h prior to plating into 96-well plates. Twenty-four hours after plating, cells were treated with CXCL1 or vehicle (0.1% BSA) at a final concentration of 10 pg/mL in complete media for a total of 5 days. Media containing CXCL1 or vehicle were replaced on Day 2, and colony formation was evaluated after 5 days in culture. Three-dimensional projection images (100x total magnification) of the colonies in each sample were obtained by assembling Z-stacks comprised of 60 optical sections, at an interval of ~30 microns, using the Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. The 60 images were then focused into a single representative image per well utilizing the extended depth of focus function of the Nikon Elements AR software, and the total number of colonies in each focused image was manually counted. Twelve replicates for each condition were plated for each independent experiment.

Statistical analysis

Samples were plated/run in triplicate, unless otherwise indicated, and all experiments were performed at least three times. Data represent mean and SEM of one representative experiment, and one representative experiment/image is shown. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed, non-paired Student’s t-test, and data are reported significant as follows: * if p ≥ 0.05, ** if p ≥ 0.01, and *** if p ≥ 0.001.

Results

miR-125a expression is reduced in premalignant HBECs harboring K-ras mutation

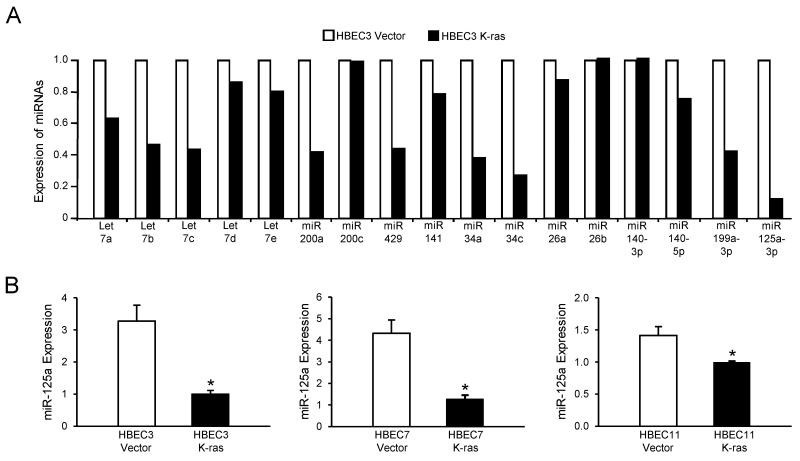

To determine the contribution of miRNAs to the malignancy-promoting effects of K-ras mutation, we characterized the miRNA expression profile in the K-ras-mutated HBEC3 cell line (HBEC3 K-ras) compared to its vector control (HBEC3 Vector) using the TaqMan™ Human miRNA Array v.2 that included 667 miRNAs. Expression levels of miRNAs that have known implications in cancer progression, including the let-7 family, the miR-200 family, and miR-34, are shown in Fig 1A. Among these miRNAs, miR-125a showed the most striking reduction in expression in K-ras-mutated HBEC3 cells compared to vector control. We then validated the microarray data by TaqMan™-based qRT-PCR in three sets of K-ras-mutated and Vector control HBEC lines, each of which was derived from an individual patient - HBEC3, HBEC7 and HBEC11. Compared to their respective vector controls, the basal expression of miR-125a is significantly reduced in all three sets of premalignant K-ras-mutated HBECs, with a 3- to 4-fold reduction seen in HBEC3 and HBEC7 K-ras lines (Fig 1B). Importantly, we observed a trend in reduction of miR-125a expression in at least one premalignant atypical adenomatous hyperplasia lesion compared to normal tissue in 5 out of 8 patient samples (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1. miR-125a expression is reduced in premalignant HBECs harboring K-ras mutation.

(A) Sample set of TaqMan Human miRNA Array v.2 data of HBEC3 K-ras cells compared to HBEC3 Vector; of these miRNAs analyzed, miR-125a was the least abundant. (B) Basal expression of miR-125a was validated by TaqMan-based qRT-PCR in three sets of Vector and K-ras-mutated HBECs. Data was normalized using RNU6B as an endogenous control. Mean ± SEM.

miR-125a expression is regulated by PEA3 in K-ras-mutated HBECs

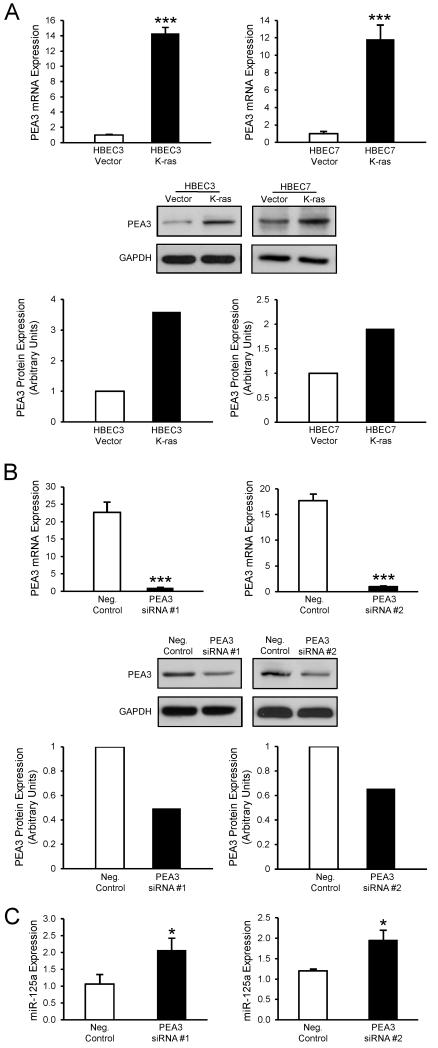

To define the mechanism underlying loss of miR-125a expression in HBEC K-ras cells compared with Vector, we investigated the role of PEA3, a member of the ETS transcription factor family. The miR-125a promoter contains five binding sites for PEA3, and chromatin immunoprecipitation has demonstrated that PEA3 association with the miR-125a promoter suppresses its activity, consequently decreasing levels of miR-125a in ovarian cancer cells (25). Importantly, PEA3 is upregulated in lung cancer and induced and activated by Ras mutation (26-28). Our data indicate that PEA3 expression (mRNA and protein levels) is abundant and elevated in HBEC3 K-ras and HBEC7 K-ras cells relative to their respective vector controls (Fig 2A). To evaluate whether genetic silencing of PEA3 could restore the reduced expression of miR-125a in K-ras-mutated HBECs, we transfected HBEC3 K-ras cells with siRNA specific for PEA3 or a non-targeting siRNA control. Knockdown of PEA3 mRNA and protein was confirmed by qRT-PCR and Western blot, respectively (Fig 2B). As seen in Fig 2C, knockdown of PEA3 expression using two different siRNA oligonucleotides both yielded significantly increased expression of miR-125a by 2-fold, suggesting that miR-125a expression is regulated by the PEA3 transcription factor in K-ras-mutated HBECs.

Figure 2. Loss of miR-125a expression is regulated by elevated PEA3 levels in K-ras-mutated HBECs.

(A) Basal mRNA and protein levels of the PEA3 transcription factor were determined in HBEC3 and HBEC7 Vector and K-ras cells by TaqMan-based qRT-PCR and Western blot, respectively. PEA3 mRNA levels were normalized to GUSB, and protein levels were normalized to GAPDH. (B) Levels of PEA3 were assessed by TaqMan-based qRT-PCR and Western blot, respectively, in HBEC3 K-ras cells 48 h after transfection with PEA3-specific siRNA. (C) miR-125a expression was assessed by TaqMan-based qRT-PCR in HBEC3 K-ras cells 48 h after knockdown of PEA3 with siRNA. Mean ± SEM.

Overexpression of miR-125a reduces tumorigenic proteins and phenotypes in K-ras-mutated HBECs

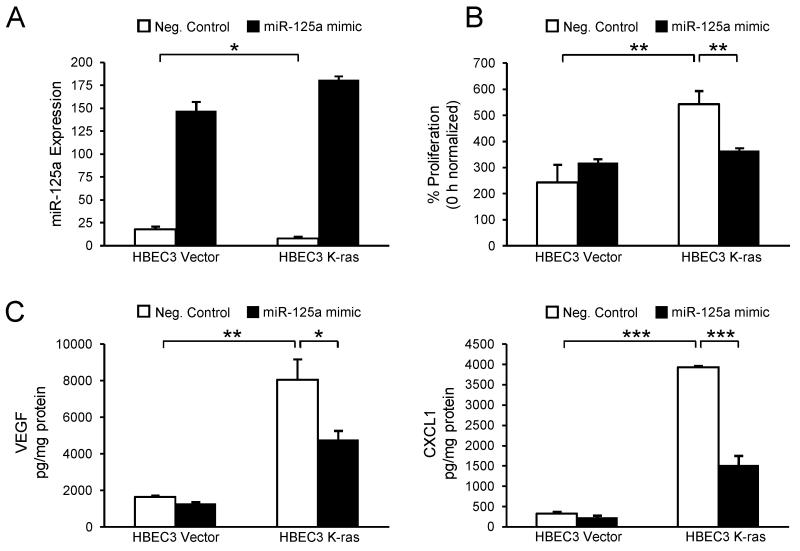

To evaluate the endogenous role of miR-125a in regulating tumorigenic phenotypes of the K-ras-mutated airway, HBEC3 Vector and K-ras cells were transfected with the miRVana™ hsa-miR-125a-3p mimic or negative control (10 nmol/L). Forced expression of miR-125a was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig 3A). Compared with negative control, transfection with the miR-125a mimic led to a significant increase in levels of miR-125a in both Vector and K-ras-mutated HBECs. To assess a functional consequence of miR-125a loss, we measured proliferation of HBEC3 Vector and K-ras cells. At baseline, HBEC K-ras cells display a higher proliferation rate as compared to Vector (Fig 3B). Interestingly, miR-125a overexpression reduced this increased proliferation rate of HBEC K-ras cells to the level of Vector (Fig 3B). To assess the impact of miR-125a loss on tumor-promoting factors in K-ras-mutated HBECs, we collected cell culture supernatants from HBEC3 Vector and K-ras cells 48 h post-transfection with the miR-125a mimic or negative control and evaluated a panel of seven inflammatory and angiogenic proteins that we selected for their demonstrated importance to lung carcinogenesis. All seven proteins were measured within the same sample utilizing a high-throughput Luminex-based multiplex assay. While a number of proteins were differentially expressed, we focused on VEGF and CXCL1 to define mechanisms of miR-125a that limit tumor growth, because computational prediction tools (TargetScan and mirRanda) identified VEGF, as well as positive regulatory factors of CXCL1 (e.g., cyclic AMP response element binding protein and poly ADP-ribose polymerase 1), as putative miR-125a targets. Further, murine models that develop ras-induced tumors have been shown to be dependent upon expression of VEGF and CXCL1, which recruit inflammatory cells and endothelial cells to the tumor (29). Data from the Luminex assay indicated that the basal protein expression of VEGF and CXCL1 is significantly higher in HBEC3 K-ras cells compared with Vector (Fig 3C). These data were then confirmed by ELISAs specific for VEGF or CXCL1 (data not shown). The increased levels of these tumorigenic proteins are in accord with the cytokine and growth factor expression profiles previously reported for NSCLC cells both in vitro and in vivo (30). Importantly, overexpression of miR-125a significantly reduced protein levels of these tumor-promoting factors in HBEC K-ras cells, while no changes were observed in Vector (Fig 3C). Further studies indicated that the reduction in protein levels of CXCL1 is regulated at the mRNA level, and in agreement with others, luciferase assays confirmed that VEGF is a direct target gene of miR-125a (data not shown) (18).

Figure 3. Overexpression of miR-125a reduces tumorigenic proteins and phenotypes in K-ras-mutated HBECs.

(A) miR-125a expression was measured by TaqMan-based qRT-PCR in HBEC3 Vector and K-ras cells 48 h post-transfection with a miR-125a mimic or negative control (10 nmol/L). Functional endpoints were also assessed 48 h post-transfection. Compared with negative control, overexpression of miR-125a in HBEC3 K-ras cells reduces proliferation (B) and expression (C) of VEGF and CXCL1, as measured by Luminex assay. Mean ± SEM.

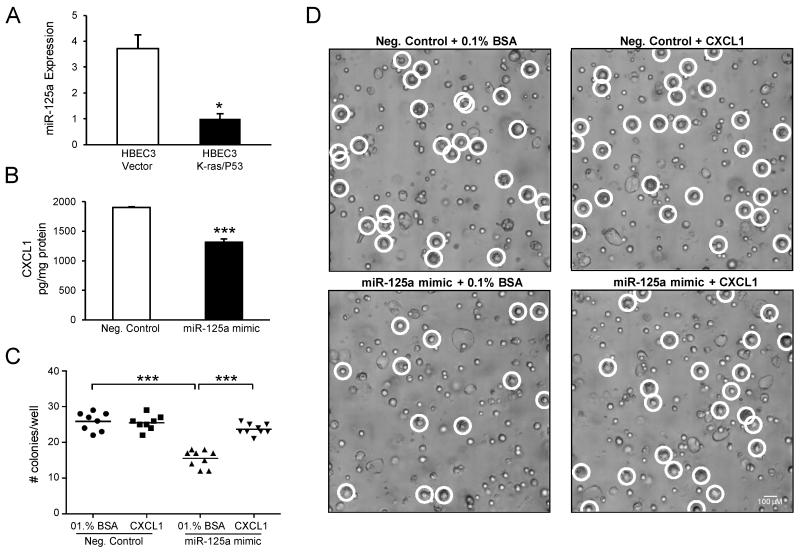

Inhibition of AIG by miR-125a overexpression is dependent on CXCL1

To assess the effect of miR-125a loss on malignant transformation in vitro, we evaluated AIG in soft agar assays as an index of transformed cell growth and tumorigenicity. Because loss of P53 function has been shown to be a critical co-oncogenic step in the malignant transformation of HBECs (22, 23), we utilized HBECs harboring an oncogenic K-ras mutation in combination with P53 knockdown (HBEC3 K-ras/P53) for the soft agar assays. As seen in Fig 4A, basal expression of miR-125a is significantly reduced in HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells compared to Vector control. In agreement with previous studies, HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells display robust AIG, while Vector cells fail to form colonies in soft agar (data not shown) (22, 23). To determine the contribution of miR-125a loss to AIG of HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells, we transfected HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells with the miR-125a mimic or negative control (1 nmol/L) 24 h prior to plating into soft agar. Compared to negative control, miR-125a overexpression markedly decreased colony formation of the HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells by 50% (Figs 4C and D). We then assessed a potential role of CXCL1 in the miR-125a-mediated reduction in AIG of HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells, as CXCL1 has been reported to contribute to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a process that has been implicated in transformation, as well as regulation of proteins involved in AIG (31). Further, miR-125a overexpression reduces protein levels of CXCL1 by 31 ± 3% in HBEC K-ras/P53 cells (Fig 4B). As quantified in Fig 4C and seen in Fig 4D, exogenous CXCL1 treatment (10 pg/mL) restored colony formation of miR-125a-transfected HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells to the level of negative control-transfected cells, whereas no changes were observed with the 0.1% BSA vehicle control.

Figure 4. Inhibition of anchorage-independent growth by miR-125a overexpression is dependent on CXCL1.

(A) TaqMan-based qRT-PCR of basal miR-125a expression in HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells compared to HBEC3 Vector. (B) miR-125a overexpression (1 pmol/L) reduces levels of CXCL1 in HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells, as determined by ELISA 48 h post-transfection. Malignant transformation of HBEC3 K-ras/P53 cells was assessed in vitro by AIG assays. Colony growth was assessed 5 days post-transfection with a miR-125a mimic or negative control (1 pmol/L), with or without exogenous CXCL1 treatment (10 pg/mL). (C) Representative focused images taken on day 5 (100x magnification) from 12 well replicates are shown; each representative image is a focused image of the 60 slices in a Z-stack. (D) Graphical representation of microscopic image quantitation; raw data images were evaluated when colony growth was ambiguous in the focused image. Mean ± SEM.

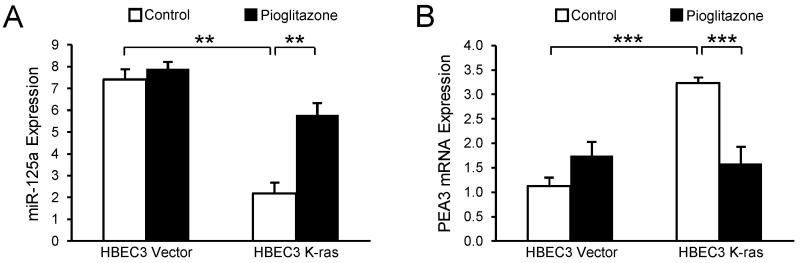

Pioglitazone upregulates miR-125a expression via PEA3

To illustrate the utility of miR-125a as a potential pharmacologic target, we determined the capacity of pioglitazone, a member of the TZD class of agents, to augment miR-125a and limit premalignancy within the “at-risk” K-ras-mutated pulmonary microenvironment. Pioglitazone was selected as a model agent for our studies based on its ability to regulate miRNAs and its capacity to modulate mediators of malignancy, such as VEGF and CXCL1 (32-34). Moreover, a 33% reduction in lung cancer risk among TZD users compared with non-users was observed, suggesting that TZDs may be chemopreventive for lung cancer in select patient populations (35). Expression of miR-125a was determined in HBEC3 Vector and K-ras cells after 48 h of treatment with pioglitazone (10 μmol/L) or the DMSO control. Interestingly, pioglitazone exposure increased miR-125a expression by 3-fold in HBEC3 K-ras cells compared with DMSO control, but did not alter levels of miR-125a in Vector cells (Fig 5A). Further studies determined that upregulation of miR-125a expression by pioglitazone in HBEC3 K-ras cells is accompanied by a significant reduction in expression of the PEA3 transcription factor (Fig 5B).

Figure 5. Pioglitazone upregulates miR-125a expression via PEA3.

TaqMan-based qRT-PCR for (A) miR-125a and (B) PEA3 mRNA expression in HBEC3 Vector and K-ras cells after 48 h treatment with pioglitazone (10 μmol/L). Mean ± SEM.

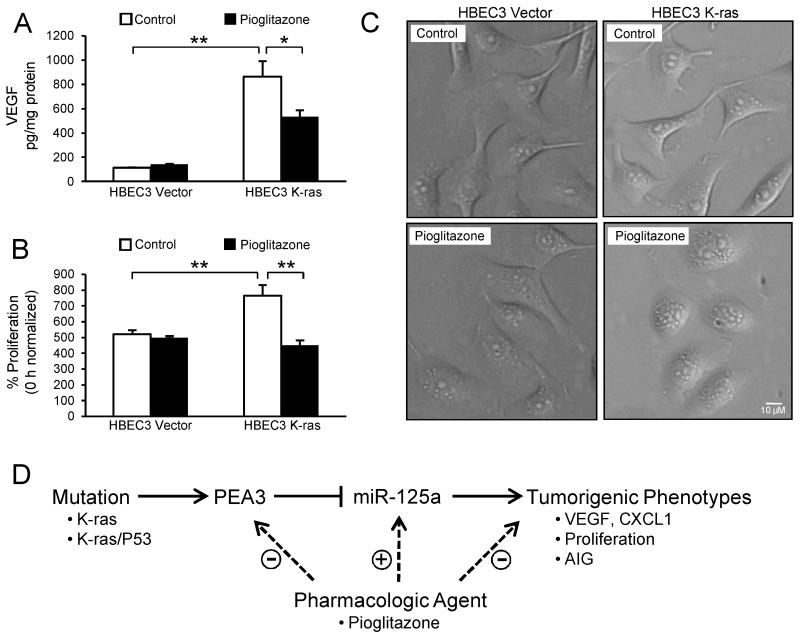

Pioglitazone exhibits similar anti-tumor activity as miR-125 overexpression in K-ras-mutated HBECs

Because pioglitazone upregulates miR-125a expression in HBEC3 K-ras cells, we determined whether pioglitazone could also limit tumorigenic phenotypes. Cell culture supernatants were collected from HBEC3 K-ras and Vector cells treated for 48 h with pioglitazone (10 μmol/L) or the DMSO control, and VEGF protein levels were measured via ELISA. Similar to forced miR-125a expression, pioglitazone significantly reduced VEGF protein levels by 38 ± 6% in K-ras-mutated HBECs, while no changes were observed in Vector cells (Fig 6A). In addition, the increased proliferation rate of HBEC3 K-ras cells was suppressed to the same level as Vector cells by pioglitazone (Fig 6B). Interestingly, 72 h of pioglitazone treatment induced a phenotypic change indicative of mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) in K-ras-mutated HBECs, while no changes were observed in Vector; HBEC K-ras cells displayed changes from a spindle-like to a more cobblestone-like morphology, typical of epithelial cells (Fig 6C).

Figure 6. Pioglitazone exhibits similar anti-tumor activity as miR-125a overexpression in K-ras-mutated HBECs.

Treatment of HBEC3 K-ras cells with pioglitazone (10 μmol/L) for 48 h (A) reduces VEGF production, (B) suppresses proliferation, and (C) induces morphological changes indicative of mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. Mean ± SEM. (D) We propose a model wherein loss of miR-125a expression in K-ras-mutated and/or K-ras/P53-mutated HBECs contributes to elevated levels of tumorigenic proteins, including VEGF and CXCL1, and increases proliferation and AIG. Treatment of K-ras-mutated HBECs with a pharmacologic agent downregulates expression of the PEA3 transcription factor, increases levels of miR-125a, and abrogates several of the deleterious downstream events associated with the mutation.

Discussion

The lack of a systematic approach for chemoprevention agent selection and the disregard for individual differences when randomizing to intervention groups have led to clinical prevention trials that have failed or, in some cases, increased the risk for lung cancer (2). In this regard, defining molecular abnormalities in the pulmonary epithelium of a given individual at-risk will facilitate rational application of chemoprevention agents with the greatest capacity to interrupt specific mutation-driven events in cancer initiation and progression. This personalized, targeted approach is expected to yield more effective cancer prevention, as it has been the recent focus in advanced stage lung cancer. To this end, we have demonstrated that loss of miR-125a expression in K-ras-mutated and/or K-ras/P53-mutated HBECs contributes to elevated levels of tumorigenic proteins, including VEGF and CXCL1, and increases proliferation as well as AIG (Fig 6D). Furthermore, treatment of K-ras-mutated HBECs with a pharmacologic agent increases levels of miR-125a by downregulating expression of the PEA3 transcription factor, and abrogates several of the deleterious downstream events associated with the mutation. Importantly, recent studies have demonstrated that expression of miR-125a is reduced in NSCLC tissues compared with adjacent normal lung tissues, and expression of miR-125a negatively correlates with pathological tumor stage and lymph node metastasis (20). These findings, in addition to the HBEC model of pulmonary premalignancy demonstrated here, suggest that loss of miR-125a expression participates in the pathogenesis of pulmonary premalignancy.

The potential of miRNAs to serve as non-invasive biomarkers for the early diagnosis of cancer has been an area of active investigation. In a seminal study by Schembri et al., the authors’ findings indicate that miRNAs are regulators of smoking-induced gene expression changes in human bronchial airway epithelial cells, suggesting that miRNA may play a role in the pathogenesis of smoking-related lung diseases (13). While a number of studies have since emerged identifying various miRNAs in lung carcinogenesis, ours is the first examination of miR-125a in the context of pulmonary premalignancy. Moreover, recent findings suggest that miRNA expression measured in readily collected samples can be used for early cancer detection (12, 36, 37). For example, in a blood-based microarray profiling of miRNA expression in preoperative serum of NSCLC patients and healthy individuals, miR-361-3p and miR-625* were identified as the two most downregulated miRNAs (38). It was further determined that both miRNAs could differentiate NSCLC from benign lesions and healthy controls. In next-generation sequencing of small RNA from human bronchial airway epithelium, miR-4423 was identified as a regulator of airway epithelium differentiation and a repressor of lung carcinogenesis (12). Interestingly, expression of miR-4423 is downregulated in the cytologically normal bronchial airway epithelium of smokers with lung cancer. This suggests that expression of miR-4423 and/or other miRNAs might be influenced by a field cancerization effect and could be useful for the early detection of lung cancer in the relatively accessible proximal airway. Importantly, studies documenting the regulation of miRNAs by diverse classes of cancer chemoprevention agents highlight their utility in the clinical setting. In a miRNA expression profiling study of rat lungs exposed to environmental cigarette smoke (ECS), ECS induced down-regulation of several families of miRNAs which regulate tumorigenic phenotypes, including apoptosis, angiogenesis, and proliferation (39). In a subsequent study, the authors demonstrated by microarray that orally administered chemopreventive agents could modulate ECS-induced alterations in miRNA expression, as well as tumorigenic phenotypes (40). As these studies highlight the potential use of miRNAs as biomarkers for NSCLC early detection and targets for NSCLC chemoprevention, our findings suggest that miR-125a may have similar potential that is worthy of further investigation.

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) has been identified as a potential target for lung cancer chemoprevention. Considerable evidence suggests that the TZD group of drugs, also known as PPARγ ligands, modulate cancer progression by inhibiting tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Utilizing in vitro and in vivo xenograft models of lung cancer, TZDs have been shown to induce growth arrest, differentiation, and apoptotic cell death, thereby inhibiting tumor growth (41-48). Currently, the TZD pioglitazone is being evaluated in an early phase chemoprevention clinical trial for subjects at elevated risk for lung cancer. To help define the role of miR-125a in pulmonary premalignancy and demonstrate its potential as a pharmacologic target, we used the TZD pioglitazone as a model agent for our studies. Interestingly, pioglitazone selectively upregulated miR-125a expression in HBEC K-ras cells through downregulation of the PEA3 transcription factor. In agreement with previous studies, pioglitazone exhibited anti-tumorigenic activity, including the reduction of proliferation and tumorigenic proteins. At baseline, HBECs are preneoplastic epithelial cells, but their epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype is highly plastic and shifts along the continuum as the HBECs are genetically manipulated and acquire full malignant potential. In accord with reports of TZD-induced morphological and molecular changes associated with differentiation of NSCLC cells (41), pioglitazone induced morphological changes indicative of MET in K-ras-mutated HBECs. It should be noted that pioglitazone is pleiotropic in its activities; therefore, the anti-tumorigenic effects we observed are likely not solely miR-125a-dependent.

Here, we report findings supporting a role for the loss of miR-125a expression in the pathogenesis of K-ras-dependent pulmonary premalignancy. Further studies will be required to determine if this miRNA can function in evaluation and selection of chemoprevention agents. In addition, our finding that miR-125a expression is reduced in at least one premalignant lesion compared to normal tissue in 5 out of 8 patient samples surveyed demonstrates the marked heterogeneity inherent to lung carcinogenesis within a given individual. Further studies will be required to confirm our data in larger numbers of premalignant lesions and to determine whether miR-125a expression levels in premalignant lesions correlate with K-ras status. Likewise, we have focused our studies on the K-ras-mutated airway epithelium, but future studies will be required to determine if miR-125a functions in the pathogenesis of premalignancy involving other mutations considered to be drivers of lung cancer pathogenesis. Understanding the contribution of specific miRNA in the pathogenesis of pulmonary premalignancy and their potential pharmacologic manipulation will be important in the future application of personalized chemopreventive agents targeted to the underlying molecular and epigenetic drivers of early lung cancer development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Ying Lin for technical assistance and the following UCLA Core Facilities for technical services and advice: the UCLA Vector Core, the UCLA Genotyping and Sequencing Core, and the CNSI Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Resource Facility at UCLA.

Financial Support: These studies were supported by funding from the following sources: NIH/NHLBI #T32HL072752 (S. Dubinett, E. Liclican, T. Walser, S. Park), NCI #U01CA152751 (S. Dubinett, T. Walser, K. Krysan, B. Gardner), NIH/NCATS UCLA CTSI #UL1TR000124 (S. Dubinett), Department of Veteran Affairs #5I01BX000359 (S. Dubinett), and NCI Lung Cancer SPORE #P50CA70907 (J. Minna, J. Larsen).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubinett SM, Spira A. Challenge and opportunity of targeted lung cancer chemoprevention. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4169–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes-Jofre M, Rueda JR, Corsini-Munoz G, Fonseca-Cortes C, Caraballoso M, Bonfill Cosp X. Drugs for preventing lung cancer in healthy people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD002141. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002141.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keith RL, Miller YE. Lung cancer chemoprevention: current status and future prospects. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:334–43. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo E, Mao JT, Lam S, Reid ME, Keith RL. Chemoprevention of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e40S–60S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buettner R, Wolf J, Thomas RK. Lessons learned from lung cancer genomics: the emerging concept of individualized diagnostics and treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1858–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton AM. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:233–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HS, Minna JD, White MA. GWAS meets TCGA to illuminate mechanisms of cancer predisposition. Cell. 2013;152:387–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perdomo C, Campbell JD, Gerrein J, Tellez CS, Garrison CB, Walser TC, et al. MicroRNA 4423 is a primate-specific regulator of airway epithelial cell differentiation and lung carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220319110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schembri F, Sridhar S, Perdomo C, Gustafson AM, Zhang X, Ergun A, et al. MicroRNAs as modulators of smoking-induced gene expression changes in human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2319–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806383106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2257–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, Osada H, Endoh H, et al. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3753–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W, Duan R, Kooy F, Sherman SL, Zhou W, Jin P. Germline mutation of microRNA-125a is associated with breast cancer. J Med Genet. 2009;46:358–60. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.063123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott GK, Goga A, Bhaumik D, Berger CE, Sullivan CS, Benz CC. Coordinate suppression of ERBB2 and ERBB3 by enforced expression of micro-RNA miR-125a or miR-125b. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1479–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bi Q, Tang S, Xia L, Du R, Fan R, Gao L, et al. Ectopic expression of MiR-125a inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting MMP11 and VEGF. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park NJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Henson BS, Kastratovic DA, Abemayor E, et al. Salivary microRNA: discovery, characterization, and clinical utility for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5473–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang L, Huang Q, Zhang S, Zhang Q, Chang J, Qiu X, et al. Hsa-miR-125a-3p and hsa-miR-125a-5p are downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer and have inverse effects on invasion and migration of lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:318. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang L, Chang J, Zhang Q, Sun L, Qiu X. MicroRNA hsa-miR-125a-3p activates p53 and induces apoptosis in lung cancer cells. Cancer Invest. 2013;31:538–44. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2013.820314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato M, Larsen JE, Lee W, Sun H, Shames DS, Dalvi MP, et al. Human lung epithelial cells progressed to malignancy through specific oncogenic manipulations. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:638–50. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0634-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato M, Vaughan MB, Girard L, Peyton M, Lee W, Shames DS, et al. Multiple oncogenic changes (K-RAS(V12), p53 knockdown, mutant EGFRs, p16 bypass, telomerase) are not sufficient to confer a full malignant phenotype on human bronchial epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2116–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasband WS. ImageJ. U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland, USA: 1997-2014. http://imagej.nih.gov/ij. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowden Dahl KD, Dahl R, Kruichak JN, Hudson LG. The epidermal growth factor receptor responsive miR-125a represses mesenchymal morphology in ovarian cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1208–15. doi: 10.1593/neo.09942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiroumi H, Dosaka-Akita H, Yoshida K, Shindoh M, Ohbuchi T, Fujinaga K, et al. Expression of E1AF/PEA3, an Ets-related transcription factor in human non-small-cell lung cancers: its relevance in cell motility and invasion. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:786–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kranenburg O, Gebbink MF, Voest EE. Stimulation of angiogenesis by Ras proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1654:23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upadhyay S, Liu C, Chatterjee A, Hoque MO, Kim MS, Engles J, et al. LKB1/STK11 suppresses cyclooxygenase-2 induction and cellular invasion through PEA3 in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7870–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adjei AA. K-ras as a target for lung cancer therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:S160–3. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318174dbf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang M, Wang J, Lee P, Sharma S, Mao JT, Meissner H, et al. Human non-small cell lung cancer cells express a type 2 cytokine pattern. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3847–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo PL, Shen KH, Hung SH, Hsu YL. CXCL1/GROalpha increases cell migration and invasion of prostate cancer by decreasing fibulin-1 expression through NF-kappaB/HDAC1 epigenetic regulation. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:2477–87. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aljada A, O’Connor L, Fu YY, Mousa SA. PPAR gamma ligands, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, inhibit bFGF- and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2008;11:361–7. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biscetti F, Straface G, Arena V, Stigliano E, Pecorini G, Rizzo P, et al. Pioglitazone enhances collateral blood flow in ischemic hindlimb of diabetic mice through an Akt-dependent VEGF-mediated mechanism, regardless of PPARgamma stimulation. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye Y, Hu Z, Lin Y, Zhang C, Perez-Polo JR. Downregulation of microRNA-29 by antisense inhibitors and a PPAR-gamma agonist protects against myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:535–44. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Govindarajan R, Ratnasinghe L, Simmons DL, Siegel ER, Midathada MV, Kim L, et al. Thiazolidinediones and the risk of lung, prostate, and colon cancer in patients with diabetes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1476–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brase JC, Wuttig D, Kuner R, Sultmann H. Serum microRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers for cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:306. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Ochiya T. Circulating microRNA in body fluid: a new potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2087–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth C, Stuckrath I, Pantel K, Izbicki JR, Tachezy M, Schwarzenbach H. Low levels of cell-free circulating miR-361-3p and miR-625* as blood-based markers for discriminating malignant from benign lung tumors. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Izzotti A, Calin GA, Arrigo P, Steele VE, Croce CM, De Flora S. Downregulation of microRNA expression in the lungs of rats exposed to cigarette smoke. FASEB J. 2009;23:806–12. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izzotti A, Calin GA, Steele VE, Cartiglia C, Longobardi M, Croce CM, et al. Chemoprevention of cigarette smoke-induced alterations of MicroRNA expression in rat lungs. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:62–72. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang TH, Szabo E. Induction of differentiation and apoptosis by ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazra S, Batra RK, Tai HH, Sharma S, Cui X, Dubinett SM. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone decrease prostaglandin E2 in non-small-cell lung cancer cells by up-regulating 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1715–20. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keshamouni VG, Arenberg DA, Reddy RC, Newstead MJ, Anthwal S, Standiford TJ. PPAR-gamma activation inhibits angiogenesis by blocking ELR+CXC chemokine production in non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7:294–301. doi: 10.1593/neo.04601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li MY, Yuan H, Ma LT, Kong AW, Hsin MK, Yip JH, et al. Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and -gamma in the development of non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:674–83. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0349OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyon CM, Klinge DM, Do KC, Grimes MJ, Thomas CL, Damiani LA, et al. Rosiglitazone prevents the progression of preinvasive lung cancer in a murine model. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2095–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reddy RC, Srirangam A, Reddy K, Chen J, Gangireddy S, Kalemkerian GP, et al. Chemotherapeutic drugs induce PPAR-gamma expression and show sequence-specific synergy with PPAR-gamma ligands in inhibition of non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2008;10:597–603. doi: 10.1593/neo.08134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satoh T, Toyoda M, Hoshino H, Monden T, Yamada M, Shimizu H, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma stimulates the growth arrest and DNA-damage inducible 153 gene in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:2171–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, James M, Wen W, Lu Y, Szabo E, Lubet RA, et al. Chemopreventive effects of pioglitazone on chemically induced lung carcinogenesis in mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3074–82. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.