Abstract

An impaired antitumor immunity is found in patients with cancer and represents a major obstacle in the successful development of different forms of immunotherapy. Signaling through Notch receptors regulates the differentiation and function of many cell types, including immune cells. However, the effect of Notch in CD8+ T-cell responses in tumors remains unclear. Thus, we aimed to determine the role of Notch signaling in CD8+ T cells in the induction of tumor-induced suppression. Our results using conditional knockout mice show that Notch-1 and -2 were critical for the proliferation and IFMγ production of activated CD8+ T cells and were significantly decreased in tumor-infiltrating T cells. Conditional transgenic expression of Notch-1 intracellular domain (N1IC) in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells did not affect activation or proliferation of CD8+ T cells, but induced a central memory phenotype and increased cytotoxicity effects and granzyme B levels. Consequently, a higher antitumor response and resistance to tumor-induced tolerance were found after adoptive transfer of N1IC-transgenic CD8+ T cells into tumor-bearing mice. Additional results showed that myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) blocked the expression of Notch-1 and -2 in T cells through nitric oxide-dependent mechanisms. Interestingly, N1IC overexpression rendered CD8+ T cells resistant to the tolerogenic effect induced by MDSC in vivo. Altogether, the results suggest the key role of Notch in the suppression of CD8+ T-cell responses in tumors and the therapeutic potential of N1IC in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells to reverse T-cell suppression and increase the efficacy of T cell-based immunotherapies in cancer.

Introduction

The key role of inflammation in the development and growth of malignancies and the recent advances in the understanding of mechanisms mediating immune suppression in individuals with tumors strongly support the use of immunotherapy as a treatment possibility in cancer (1, 2). Tumor immunotherapy encompasses diverse strategies that range from neutralizing inhibitory pathways to activating adaptive immune effector responses (3). Strategies to stimulate effector immune cells against tumors include treatment with cytokines, vaccination with tumor antigens, antigen-loaded dendritic cells, engineered introduction of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) in T cells, and adoptive transfer of antitumor T cells (3, 4). Although several T cell-based approaches have been developed to treat patients with cancer in promising phase 1-2 clinical trials, a very low clinical outcome has been obtained (5, 6). A possible explanation for the low clinical effect of T cell-based immunotherapy is the presence of an immune tolerogenic microenvironment that blocks antitumor effector responses (7). Therefore, new approaches are needed to render T cells resistant to tumor-induced suppression or to switch the suppressive environment into one that promotes antitumor effector responses.

The Notch family of receptors is a highly conserved pathway that controls the development, differentiation, and function of many cell types, including immune cells (8). Mammals have four Notch receptors (Notch-1-4) that are bound by five ligands of the Jagged (Jagged-1 and Jagged-2) and the Delta-like (DLL1, DLL3, and DLL4) families (9). Binding of Notch receptors to their ligands induces proteolytic processing, including the cleavage by the γ secretase complex, leading to the membrane release and nuclear translocation of the Notch intracellular active domain (NICD). Once there, NICD complexes with the recombination signal-binding protein-J (RBP-J, also known as CSL) and the mastermind-like (MAML) co-activator, promoting transcription of multiple genes (10). Moreover, NICD interacts with members of the NF-κβ pathway, inducing non-canonical regulation of various transcripts (11, 12).

Signaling through Notch plays a critical role on the development and function of T cells (13, 14). Treatment of activated mature T cells with γ secretase inhibitors (GSI) decreased T-cell activation (15), proliferation (16, 17), survival (18), cytokine production (17, 19), and cytotoxicity (19). The role of Notch signaling in the modulation of CD4+ T-helper (Th) cell differentiation and function is well established (20-22). Ligation of Notch to DLL1 and 4 ligands promoted Th1 responses, whereas the engagement of Jagged-1 and -2 ligands induced the development of Th2 and regulatory T cell (Treg) populations (20, 23-25). Furthermore, conditional deletion of Notch-1 and -2 in T cells impaired the expression and generation of Th17 and Th9 populations (26, 27). However, the involvement of Notch signaling in the activation and function of CD8+ T cells is less clear. CD8+ T cells activated in the presence of either a GSI or a blocking anti-Notch-1 antibody had an impaired lytic capacity (19). Similar alterations in effector CD8+ T-cell responses were found after knockdown of Notch-2 (28). Moreover, Jagged-1 expression suppressed collagen-induced arthritis by providing negative signals in CD8+ T cells (29). Interestingly, treatment of tumor-bearing mice with agonistic antibodies against Notch-2 or DLL1- or DLL4-Fc fusion proteins led to antitumor responses (30-32), suggesting the potential therapeutic effect of promoting Notch signaling in cancer. However, these therapeutic approaches were systemic and did not specifically target T cells.

In this study, we aimed to determine the effect of Notch signaling in the antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells. Our results show the critical role of Notch-1 and -2 in CD8+ T-cell functions. Conditional expression of transgenic N1IC in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells promoted cytotoxic responses. Consequently, an increased antigen-specific antitumor effect and high resistance to tumor-induced CD8+ T-cell tolerance were found in tumor-bearing mice receiving T cells engineered to overexpress N1IC. Furthermore, MDSC blocked the expression of Notch-1 and -2 in T cells in a nitric oxide-dependent manner. Also, transgenic-N1IC rendered CD8+ T cells resistant to the tolerogenic effect of MDSC. Altogether the results suggest the relevance of Notch-1 and -2 in antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses and the potential therapeutic benefit of using transgenic-N1IC as an adjuvant for T cell-based immunotherapy in cancer.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 mice (6 to 8-week-old female) were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). Floxed transgenic Rosa-driven N1IC-GFP (33), floxed null Notch-1, floxed null Notch-2, granzyme B Cre recombinase, CD2 Cre recombinase, anti-OVA257-264 (siinfekl) OT-1, and CD45.1+ mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). N1IC/granzyme B Cre/OT-1 mice were backcrossed into C57BL/6 for 9 generations to finally obtain the genotype N1IC+/+; OT-1+/+; granzyme B Cre +/− mice (referred herein as N1IC mice). As controls, we used N1IC+/+; OT-1+/+; granzyme B Cre −/− mice (defined as N1ICf/f mice). Furthermore, floxed null Notch-1 and/or -2 mice were bred with mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the granzyme B promoter, which enabled the conditional knockdown of Notch-1 and/or -2 in activated CD8+ T cells. All experiments using animals were approved by the LSU-IACUC.

Cell lines

Lewis lung carcinoma (3LL) and EL-4 thymoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and maintained in RPMI 1640 (Lonza-Biowhittaker, Walkerville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 25 mM Hepes (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 4 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), and 100 U/ml of penicillin, streptomycin (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Ovalbumin-expressing 3LL cells (3LL-OVA) were generated by transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with a plasmid encoding cytosolic chicken ovalbumin (34) and harboring a neomycin resistance cassette (Addgene; plasmid 25097). 3LL-OVA clones were selected in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 500 μg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Tumor volume was determined using calipers and calculated using the formula [(small diameter)2 × (large diameter) × 0.5 ]. All cell lines were tested and validated to be mycoplasma-free; no additional authentication assays were performed.

Antibodies and Reagents

Purified antibodies against CD3 (clone 1452C11), CD28 (clone 37.51), CD8α (clone 53-6.7), CD11b (clone M1/70), Gr-1 (clone RB6-8C5), and T-bet (clone 04-46) were obtained from Becton Dickinson Biosciences (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Polyclonal antibodies against perforin A (H-35) and Fas-L (C-178) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against granzyme B (#4275), RBP-J (clone D10A4), NF-κB p65 (clone D14E12), Runx3 (D9K6L), Eomes (#4540), and Notch 2 (clone D76A6) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-Notch-1 (clone mN1A), IFMγ (clone XMG1.2), and CD107a (clone lamp-1) antibodies were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-β-actin antibody (clone AC-74) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). GSI peptide Z-Ile-Leu-CHO, L-NG-Monomethylarginine (L-NMMA), Nω-hydroxy-nor-Arginine (NN), and D-NGMonomethylarginine (D-NMMA) were obtained from EMD Millipore (Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ). Siinfekl peptide was obtained from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA). NF-κB inhibitor pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PTDC) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Isolation of T cells and MDSC

CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of mice using negative isolation kits (Life Technologies). Purity ranged between 95% and 99%, as tested by flow cytometry. Furthermore, MDSC were isolated from tumors previously digested with DNAse and Liberase (Roche USA, Branchburg, NJ), as previously described (35). Briefly, MDSC were isolated by positive selection using anti-Gr-1 antibodies (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and their ability to suppress T-cell proliferation tested in each experiment. Purity for each population ranged from 90%-99%, as measured by flow cytometry.

T-cell Proliferation Assay

Proliferation of wild type CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells was measured using the intracellular dye Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies) after activation with 0.5 μg plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28. Proliferation of N1IC and N1ICf/f cells was evaluated after labeling cells with proliferation dye eFluor® 670 (eBioscience) and activation with siinfekl (2 μg/ml). Proliferation of N1IC and N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells in vivo was monitored using incorporation of 5-bromo2’deoxyuridine (BrdU) (BD Biosciences). Briefly, CD45.1+ mice were injected i.v. with 5 × 106 CD8+ T cells from CD45.2+ N1IC or N1ICf/f mice, followed by vaccination with 0.5 μg siinfekl in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA). Four days later, mice were injected i.p. with 200 μg/mouse of BrdU (BD Biosciences), and 24 hours later, BrdU incorporation was measured in CD45.2+ CD8+ cells using the APC-BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences). Results are expressed as the percentage of CD45.2+ CD8+ BrdU+ cells in spleens.

Adoptive Cellular therapy

CD45.1+ mice bearing palpable 3LL-OVA tumors (for 7 days) received 5 × 106 CD8+ T cells from CD45.2+ N1IC or N1ICf/f mice. The next day, mice were vaccinated with 0.1 mg siinfekl s.c. and monitored for tumor growth kinetics or IFMγ production by ELISpot. Alternatively, splenocytes from N1IC and N1ICf/f mice were activated in vitro with 2 μg/ml siinfekl for 72 hours, after which CD8+ T cells were isolated using negative selection kits and 5 × 106 cells adoptively transferred into CD45.1+ mice bearing 3LL-OVA tumors for 7 days. To determine the effect of N1IC in tumor-induced tolerance, lymph nodes were harvested 10 days after adoptive transfer and tested for the presence of CD45.2+ CD8+ T cells. In addition, they were activated with 2 μg/ml siinfekl and monitored for IFMγ production by ELISpot (R and D systems).

Detailed methodological description of cytotoxicity assays, tolerogenic effect of MDSC, western blot and immunoprecipitation, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP), quantitative PCR, and statistical analysis are included in the Supplementary Methods section.

Results

Notch-1 and -2 regulate CD8+ T-cell function and are inhibited in T cells from tumors

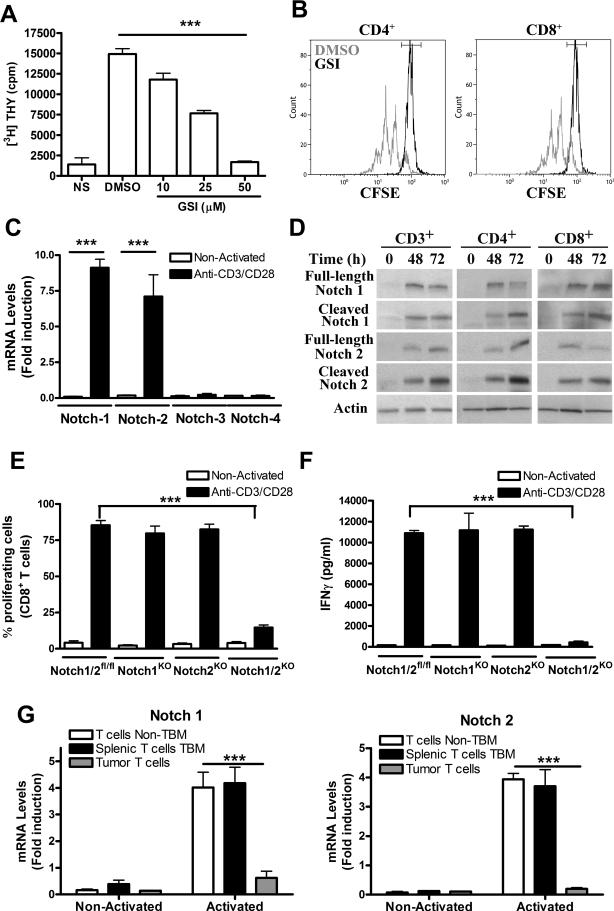

To understand the potential role of T cell-Notch signaling as a mediator of T-cell dysfunction in tumor-bearing host, we first determined the effect of Notch inhibition in T-cell proliferation. As previously demonstrated (16-19), inhibition of Notch signaling in activated T cells using a GSIimpaired T-cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). This anti-proliferative effect was observed in both activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1B). We then aimed to establish the isoforms of Notch induced after T-cell activation. An increased expression of Notch-1 and -2 mRNA, but not Notch-3 or -4, was found in anti-CD3/CD28-activated T cells (Fig. 1C). This induction of Notch-1 and -2 mRNA after T-cell activation was confirmed at the protein levels in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and correlated with increased expression of both full length and cleaved forms of Notch-1 and -2 (Fig. 1D). Then, we investigated the significance of the expression of Notch-1 and -2 in CD8+ T-cell proliferation and IFMγ production. Floxed mutant Notch-1 and/or -2 mice were bred with mice expressing Cre recombinase from the granzyme B promoter, which conditionally knockdown these Notch isoforms preferentially in activated CD8+ T cells. Individual deletion of Notch-1 or -2 did not impair CD8+ T-cell proliferation (Fig. 1E) and IFMγ production (Fig. 1F). However, activated CD8+ T cells lacking both Notch-1 and -2 had an impaired cell proliferation and IFMγ production (Fig. 1E-F), suggesting a relevant, but functionally redundant role, of Notch-1 and -2 in CD8+ T-cell function.

Figure 1. Induction of Notch-1 and -2 regulate CD8+ T-cell functions and are inhibited in tumor-infiltrating T cells.

(A) CD3+ T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 (0.5 μg each) in the presence of increasing concentrations of GSI, Z-Ile-Leu-CHO. Proliferation was determined after 72 hours by [3H]-thymidine uptake. Activated T cells cultured with DMSO and non-stimulated T cells (NS) were used as controls. Results represent mean ± SD from 3 similar independent experiments. ***, P< 0.001. (B) CFSE-labeled CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were activated as (A) with 30 μM GSI and proliferation determined 72 hours later by flow cytometry. Histograms are a representative result from 3 experiments. (C) Notch-isoforms mRNAs were measured in T cells activated for 48 hours. Results represent mean ± SD from 2 experiments. ***, P< 0.001. (D) CD3+, CD4+, or CD8+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 and whole cell extracts harvested after 48 and 72 hours. Western blot are representative results of 4 repeats. (E and F) CFSE-labeled CD3+ T cells from floxed and conditional-null Notch-1 and -2 mice were activated as (A) and monitored for cell proliferation by CFSE. Supernatants were harvested and IFMγ levels measured by ELISA. Results represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ***, P< 0.001. (G) T lymphocytes were isolated from tumors and spleen of mice bearing s.c. 3LL tumors for 17 days or spleens from mice without tumors. T cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours and tested for Notch-1 and -2 mRNA by real-time PCR. Results represent mean ± SD from 4 different animals and tested in triplicates. ***, P< 0.001.

Next, we tested the expression of Notch-1 and -2 in T cells from tumors and spleens of tumor-bearing mice (TBM) and controls. Induction of Notch-1 and -2 was found in activated T cells from spleens of 3LL-bearing mice and controls, but not in T cells from tumors (Fig. 1G), suggesting the negative effect of the tumor microenvironment on the induction of Notch-1 and -2 in T cells.

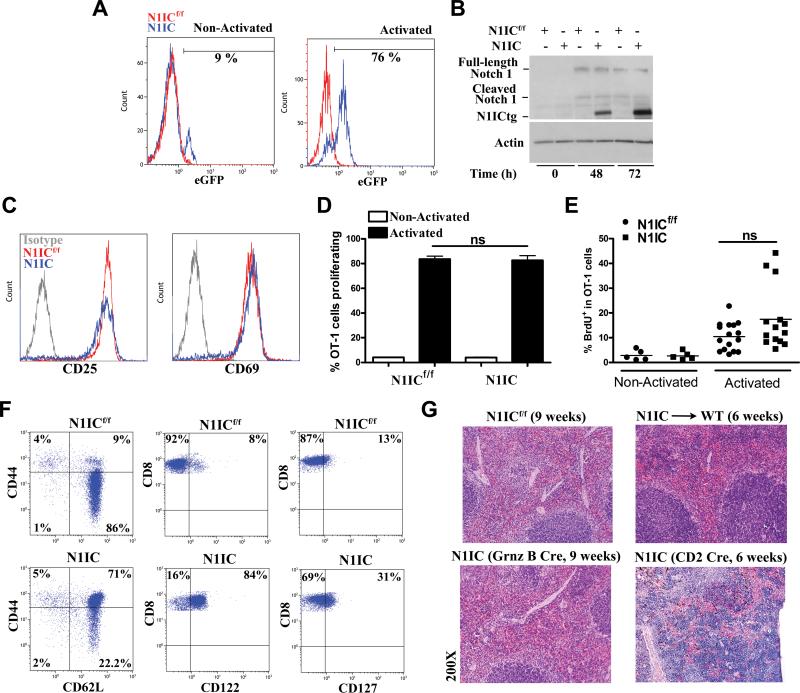

Effect of transgenic N1IC on CD8+ T-cell activation and proliferation

To determine the effect of increasing Notch-1 signaling in CD8+ T cells, we generated a strain of mice, in which N1IC-tagged to green fluorescent protein (GFP) was conditionally expressed in activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. This was achieved by crossing transgenic floxed N1ICGFP mice, anti-OVA257-264 (siinfekl) OT-1 mice, and mice expressing Cre recombinase from the granzyme B promoter (N1IC+/+; OT-1+/+; granzyme Cre +/−; herein defined as N1IC mice). Floxed OT-1 mice lacking granzyme B Cre were used as controls and referred as N1ICf/f. To validate the model, we tested the expression of transgenic N1IC in activated and non-activated CD8+ T cells from N1IC and N1ICf/f mice after testing the GFP reporter using flow cytometry or by measuring transgenic N1IC by immunoblot. Increased percentages of CD8+ T cells expressing N1IC-GFP were found in activated T cells from N1IC mice, but not in stimulated controls or N1IC cells without activation (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, a dramatic increase in the expression of transgenic N1IC, and similar levels of endogenous full length and cleaved Notch-1, were found in siinfekl-activated CD8+ T cells from N1IC mice (Fig. 2B), as compared to those from N1ICf/f mice. Moreover, transgenic expression of N1IC did not alter the expression of early activation markers CD25 and CD69 (Fig. 2C), or the proliferation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2 D-E), ruling out the effect of transgenic N1IC in T-cell activation and proliferation. Interestingly, phenotypic analysis showed an increased expression of central memory markers CD44high CD62L+, CD122+, and CD127+ (Fig. 2F), but not cytotoxic-linked markers KLRG1 and granzyme B (data not shown), in naive CD8+ T cells from N1IC mice, compared to cells from N1ICf/f controls, suggesting a potential effect of transgenic N1IC on effector T-cell responses. Because N1IC is a major mediator in the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), we tested whether N1IC mice or those transferred with activated N1IC CD8+ T cells developed ALL. A normal spleen morphology was observed in N1ICf/f, N1IC (9 weeks after birth), or wild type mice transferred with pre-activated N1IC CD8+ T cells (6 weeks after transfer) (Fig. 2G). In contrast, development of ALL, as suggested by the accumulation of lymphoblastic cells in the spleen, was noted in N1IC-CD2-Cre mice that expressed transgenic N1IC in immature T cells (Fig. 2G). Thus, expression of N1IC in mature activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells did not result in ALL development.

Figure 2. Transgenic N1IC in CD8+ T cells does not regulate activation and proliferation, but induces markers linked to central memory.

(A) Spleens from N1ICf/f or N1IC mice were cultured in the presence or absence of siinfekl (2 μg/ml) for 72 hours, after which eGFP expression was determined in gated CD8+ T cells. FACS histograms are a representative experiment of 5 independent repeats. (B) Cells from N1ICf/f or N1IC mice were activated as (A) and extracts collected after 48 and 72 hours and tested for Notch-1 and -2 by western blot. A representative experiment of 4 is shown. (C) Expression of CD25 and CD69 was determined in siinfekl-activated N1ICf/f or N1IC cells (24 hours). A representative FACS histogram from 5 experiments is shown. (D) eFluor® 670-labeled N1ICf/f or N1IC cells were cultured in the presence or absence of siinfekl for 72 hours, after which cell proliferation was established in CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. Results represent mean ± SD of the percentage of cells proliferating from 3 independent experiments. Ns= Non-statistical significance, P > 0.01. (E) CD45.1+ mice previously injected with 5 × 106 CD8+ T cells from CD45.2+ N1IC or N1ICf/f mice, were immunized with 0.5 μg siinfekl in IFA. Four days later, mice were injected i.p. with BrdU, and the percentage of CD45.2+ CD8+ BrdU+ cells was established by flow cytometry. Results represent mean ± SD from 2 similar independent experiments (N1ICf/f n=16; N1ICf/f n=14). Ns= Non-statistical significance, P > 0.01. (F) Representative FACS dot plot experiment showing the baseline expression of CD44, CD62L, CD122, and CD127 in CD8+ T cells from N1ICf/f or N1IC mice. Experiment was repeated with 6 mice, obtaining similar results. (G) H&E staining to evaluate spleen morphology in 9 weeks old N1ICf/f (n=5, upper left) and N1IC (n=5, lower left) mice, wild type mice transferred with 5 × 106 pre-activated N1IC (n=5, 6 weeks after transfer, upper right), and N1IC-CD2 Cre recombinase (n=5, lower right, 6 weeks after birth).

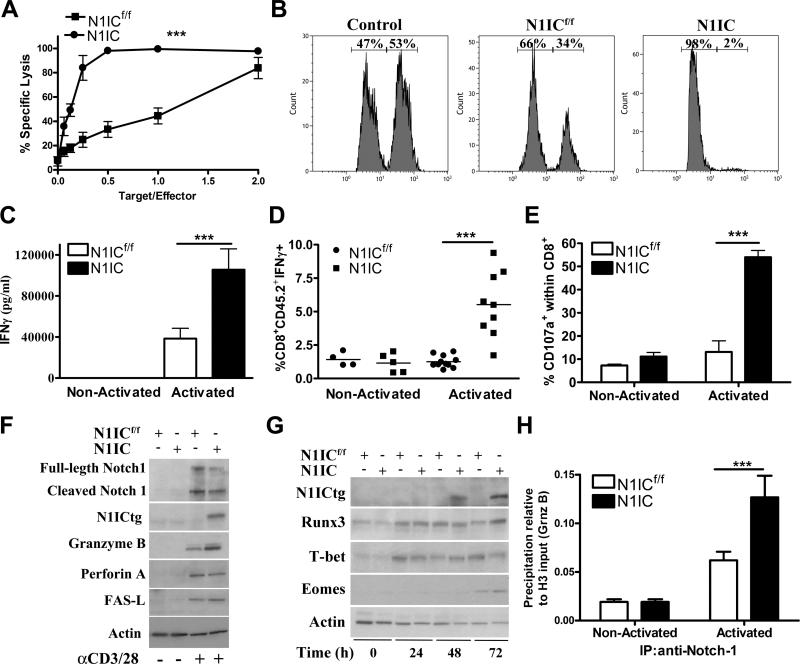

Transgenic N1IC promotes cytotoxic responses in activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells

Because the elevated expression of central memory markers and previous reports showing the inhibitory role of GSI in effector T-cell responses (15-19), we aimed to determine the effect of transgenic expression of N1IC in cytotoxic responses of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Thus, splenocytes from N1ICf/f or N1IC mice were activated with siinfekl for 72 hours, after which CD8+ T cells were sorted and co-cultured with 51Chromium-labeled EL4 tumor cells loaded with siinfekl. A higher cytotoxicity against siinfekl-loaded EL4 cells was displayed by activated N1IC CD8+ cells, as compared to that triggered by N1ICf/f cells (Fig. 3A). To test the effect of N1IC in T-cell cytotoxicity in vivo, mice were injected i.v. with effector N1IC or N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells, followed by adoptive transfer of siinfekl-loaded splenocytes labeled with high CFSE and control-splenocytes labeled with low CFSE. A higher reduction of siinfekl-loaded splenocytes was observed in mice receiving N1IC CD8+ T cells, as compared to those receiving N1ICf/f cells (Fig. 3B). In addition, the elevated cytotoxicity triggered by N1IC-expressing CD8+ T cells correlated with a higher production of IFMγ in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3C-D), higher levels of degranulation marker CD107a (Fig. 3E), and increased expression of granzyme B (Fig. 3F). However, similar levels of perforin and Fas-L were found in activated N1IC and N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells. Also, the ability of N1IC to promote effector pathways did not alter the expression of transcription factors regulating cytotoxic T-cell responses, including Runx3, Eomes, and T-bet (Fig. 3G), suggesting a potential direct effect of N1IC. In fact, a higher endogenous binding of Notch-1 to granzyme B promoter was found, using ChIP assays, in activated CD8+ T cells from N1IC mice, compared to cells from N1ICf/f mice (Fig. 3H), confirming previous studies showing the direct binding of Notch isoforms to granzyme B in activated T cells (19, 28).

Figure 3. Conditional expression of N1IC in activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells directly promotes cytotoxic T-cell responses.

(A) Splenocytes from N1ICf/f or N1IC mice were activated with siinfekl (2 μg/ml) for 72 hours, after which CD8+ T cells were negatively sorted and co-cultured at different ratios with 51Chromium-labeled EL4 tumor cells loaded with siinfekl. Supernatants were collected 8 hours later and cpm calculated. Results represent mean ± SD from 3 similar independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (B) 5 ×106 N1IC or N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells activated with siinfekl for 72 hours were adoptively transferred into mice. The same mice then received 3 X106 cells of a 1:1 ratio of siinfekl-loaded splenocytes labeled with high CFSE (1 μM) and control-splenocytes labeled with low CFSE (0.1 μM). The presence of CFSE-labeled cells was determined 24 hours later by flow cytometry in CD8Neg cells. FACS histograms are a representative experiment of 3 replicates. (C) N1ICf/f or N1IC cells were cultured in the presence or absence of siinfekl for 72 hours, after which supernatants were collected and tested for IFMγ by Elisa. Results represent mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (D) 5 × 106 CD8+ T cells from CD45.2+ N1IC or N1ICf/f mice were adoptively transferred into CD45.1+ mice, followed by vaccination with 0.5 μg siinfekl in IFA. Spleens were harvested 4 days later and challenged with siinfekl for 24 hours, after which the percentage of CD45.2+ CD8+ IFMγ+ cells was monitored by flow cytometry. Results represent mean ± SD from 2 similar independent experiments (N1ICf/f n=10; N1ICf/f n=9). ***, P < 0.001. (E) Expression of CD107a was determined in cells activated as described in (C). Results represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (F and G) CD8+ T cells from N1IC or N1ICf/f mice were activated with siinfekl for 24-72 hours, after which whole cell extracts were collected and used for immunoblot. Representative illustrations from 3 independent experiments are shown. (H). ChIP assays to detect the endogenous binding of Notch-1 to granzyme B promoter were assessed in N1IC or N1ICf/f cells cultured with and without siinfekl for 48 hours, as described in the Methods. Results represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

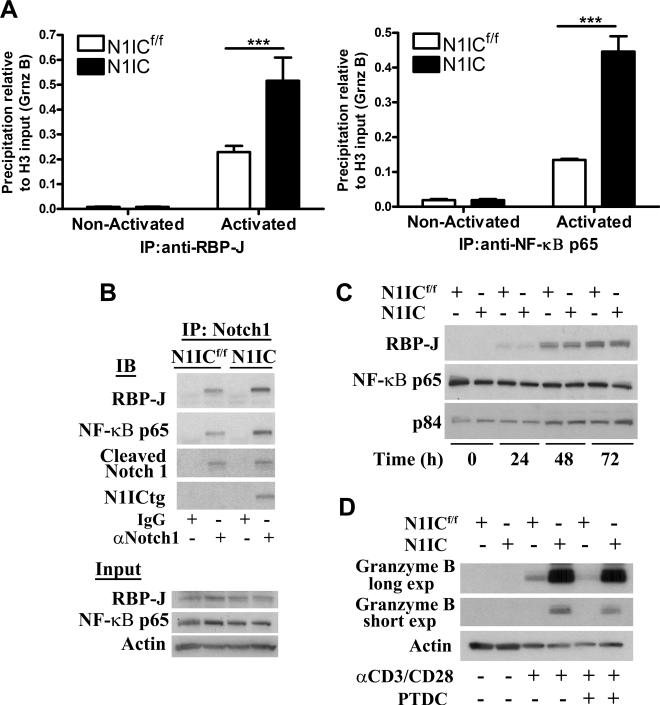

To test whether N1IC regulated granzyme B expression through canonical or non-canonical pathways, we monitored the endogenous binding of canonical member RBP-J and non-canonical member NFκB p65 to granzyme B promoter using ChIP assays. An elevated binding of both RBP-J and NFκB p65 to granzyme B promoter was detected in activated N1IC CD8+ T cells, compared to N1ICf/f cells (Fig. 4A). In addition, higher levels of RBP-J and NFκB were found after immunoprecipitation of Notch-1 in activated N1IC cells, compared to that in N1ICf/f controls (Fig. 4B). The expression of transgenic N1IC appears to be the major determinant in the formation of the complexes, as similar levels of RBP-J and NFκB p65 were detected in N1IC and N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4C). To confirm the role of NF-κB in the increased expression of granzyme B in N1IC CD8+ T cells, we used the NF-κB inhibitor PTDC. A partial prevention in granzyme B induction was found in PTDC-treated N1IC and N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that N1IC regulates granzyme B expression by direct amplification of both canonical and non-canonical pathways.

Figure 4. Transgenic N1IC regulates granzyme B expression by amplification of canonical and non-canonical pathways.

(A) ChIP assays to monitor endogenous binding of RBP-J and NF-κB to granzyme B promoter were assessed in N1IC and N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells cultured with or without siinfekl for 48 hours. Results represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (B) Immunoprecipitations were achieved using 200 μg of protein extracts from activated N1IC and N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells and 2 μg anti-Notch-1 or control IgG antibodies. After overnight incubation, protein G plus-captured complexes were analyzed for Notch-1 (cleaved and transgenic), RBP-J, and NF-κB p65 by western blot. As input controls, we used 10 μg of extracts from each experimental group before immunoprecipitation. Representative illustrations are from 2 experiments. (C) Kinetics for RBP-J and NF-κB p65 in activated N1IC or N1ICf/f cells. Representative blotting from 3 independent repeats. (D) N1IC and N1ICf/f cells were activated with siinfekl in the presence or absence of PTDC (150 nM). Granzyme B levels were tested 72 hours later. Representative illustrations from 3 independent experiments are shown.

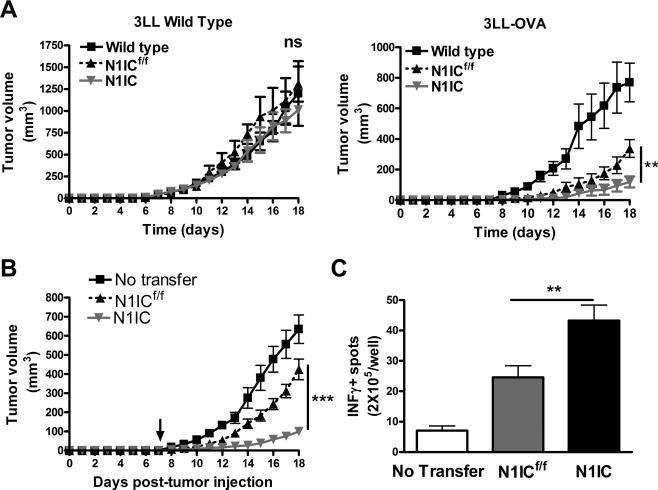

Transgenic N1IC in CD8+ T cells blocks tumor growth and enhances immunotherapy

To determine the effect of N1IC expression in activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in tumor growth, N1IC and N1ICf/f mice were injected with 3LL cells expressing the model-antigen ovalbumin (OVA) or with 3LL controls. In agreement with the high repertoire of anti-OVA T cells present in floxed and N1IC mice, there was a similar growth of 3LL cells in C57BL/6, N1IC, and N1ICf/f mice (Fig. 5A). However, a retardation of 3LL-OVA growth was found in N1ICf/f mice, which was more pronounced in N1IC mice (Fig. 5A), suggesting a higher antigen-specific antitumor effect in N1IC mice. To confirm these results, we investigated the effect of transgenic-N1IC in T cell-based immunotherapy. CD45.1+ mice were injected s.c. with 3LLOVA for 7 days, after which they were adoptively transferred with naïve CD8+ T cells from N1IC or N1ICf/f mice (CD45.2+), and immunized with siinfekl. Then, mice were monitored for tumor growth and IFMγ production. A higher antitumor effect was observed in mice receiving N1IC CD8+ T cells, as compared to those transferred with the same number of N1ICf/f cells (Fig. 5B). In addition, higher numbers of cells producing IFMγ were detected in lymph nodes of tumor-bearing mice receiving N1IC cells after vaccination and activation ex vivo with siinfekl, as compared to activated lymph nodes from control mice (Fig. 5C). This suggests the beneficial effect of the transgenic N1IC in CD8+ T cell-based cancer immunotherapy.

Figure 5. Transgenic N1IC in activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells block tumor growth.

(A) 106 3LL or 3LL-OVA cells were s.c. injected in N1IC or N1ICf/f mice. Tumor volumes were measured using calipers, as described in the Methods. Results represent mean ± SD from 2 independent experiments (N1ICf/f n=7; N1ICf/f n=7). Ns= Non-statistical significance, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.001. (B) CD45.1+ mice were injected s.c. with 3LL-OVA for 7 days, after which they were adoptively transferred with naïve CD8+ T cells from N1IC or N1ICf/f mice (CD45.2+), and immunized with siinfekl. Results represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. N1ICf/f n=22; N1ICf/f n=22). ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01. (C) Lymph nodes collected 10 days after immunization from B were challenged with siinfekl and the production of IFMγ measured using ELISpot. Results represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. **, P < 0.01.

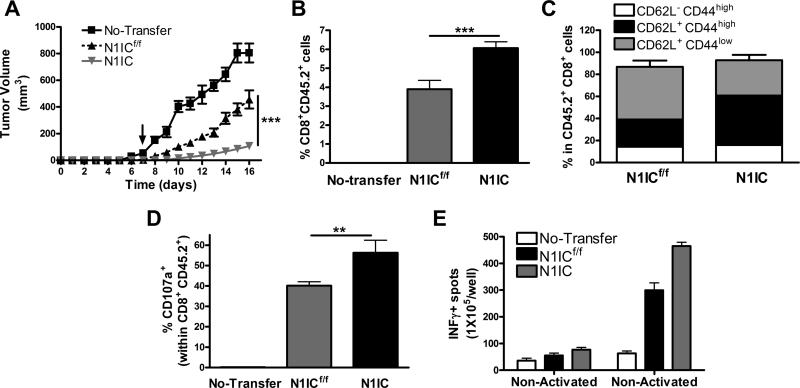

Expression of N1IC in antigen-specific T cells overcomes tumor-induced tolerance

To determine the effect of the expression of N1IC in tumor-induced tolerance, N1IC and N1ICf/f CD8+ T cells pre-activated in vitro for 48 hours, were transferred into CD45.1+ mice bearing 3LL-OVA cells for 7 days, after which mice were followed for tumor growth. A higher anti-tumor effect was induced after adoptive transfer of pre-activated N1IC CD8+ T cells, compared to that induced by N1ICf/f controls (Fig. 6A). In addition, higher numbers of CD45.2+ CD8+ T cells in tumors (Fig. 6B) and elevated expression of central memory markers CD44high CD62L+ in CD45.2+ cells (Fig. 6C) were found in mice transferred with N1IC cells, compared to mice receiving N1ICf/f controls. Also, increased levels of CD107a in CD45.2+ cells (Fig. 6D) and higher numbers of cells producing IFMγ (Fig. 6E) were noted in siinfekl-activated lymph nodes from mice receiving N1IC cells, as compared to those transferred with N1ICf/f. This suggests the beneficial effect of the transgenic expression of N1IC in T cells in overcoming tumor-induced T-cell tolerance.

Figure 6. Expression of N1IC in antigen-specific T cells enhances the efficacy of T cell-based immunotherapy.

(A) 5 × 106 CD8+ T cells N1IC or N1ICf/f pre-activated in vitro for 48 hours were adoptively transferred into mice bearing 3LL-OVA tumors for 7 days. Tumor volume was monitored, as described in the Methods. Results represent mean ± SD from 2 similar experiments. N1ICf/f n=8; N1ICf/f n=8. ***, P < 0.001. (B and C) Single cell suspensions from tumors from (A) were collected and monitored for the percentage of CD45.2+ CD8+ T cells (B) and CD44 and CD62L in CD45.2+ cells by FACS. (C). Results represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. N1ICf/f n=6; N1ICf/f n=6. ***, P < 0.001. (D and E) Spleens (D) and lymph nodes (E) were harvested 10 days after immunization and challenged with siinfekl for 24 hours, after which they were tested for CD107a (D) and production of IFMγ (E) by flow cytometry and ELISpot, respectively. Results represent mean ± SD from 2 similar independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001.

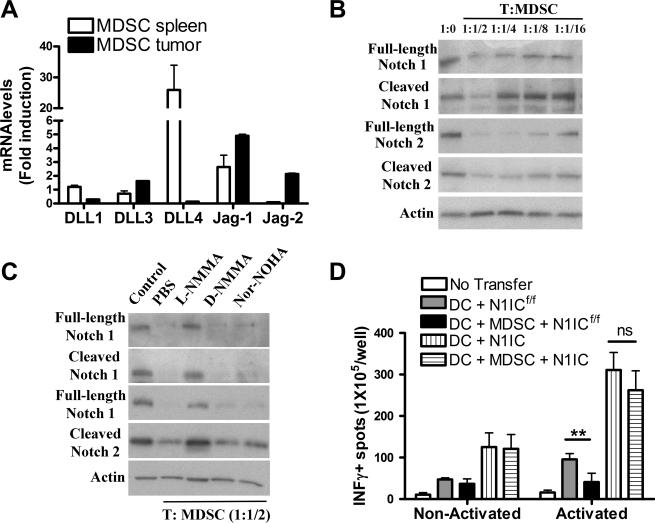

Role of Notch in the suppression of T-cell responses by tumor-infiltrating MDSC

We determined the role of MDSC as modulators of Notch signaling in T cells. MDSC carried an increased ability to trigger Notch signaling, as suggested by Jagged-1 and Jagged-2 expression in tumor-infiltrating MDSC, and DLL1 and DLL4 in splenic MDSC (Fig. 7A). However, MDSC prevented the expression of full length and cleaved Notch-1 and -2 in T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7B). MDSC blocked the expression of T-cell Notch-1 and -2 in a nitric oxide-dependent manner, as the addition of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, L-NMMA, but not the arginase inhibitor Nor-Noha or the inactive NO synthase inhibitor D-NMMA, restored the expression of full-length and cleaved Notch-1 and -2 in T cells (Fig. 7C). Then, we determined whether the expression of transgenic N1IC overcome the tolerogenic effect of MDSC in vivo (36-38). Therefore, CD8+ T cells from CD45.2+ N1IC or N1ICf/f mice were adoptively transferred into CD45.1+ congeneic recipients, followed by immunization with both mature dendritic cells (DC) and/or tumor-associated MDSC pulsed with siinfekl peptide. Five days later, mice received an additional injection with siinfekl-loaded MDSC, and after 5 days, the draining lymph nodes were collected, activated with siinfekl, and tested for IFMγ production using ELISpot. A significant decrease of IFMγ production was found in lymph nodes from immunized mice that were given MDSC and N1ICf/f T cells, compared to vaccinated mice receiving N1ICf/f T cells (Fig. 7D). In contrast, an enhanced production of IFMγ was observed in immunized mice transferred with T cells from N1IC mice, which was not significantly impaired after co-injection with MDSC (Fig. 7D). This suggests the resistance of antigen-specific T cells expressing N1IC to the tolerogenic effect induced by tumor-associated MDSC in vivo.

Figure 7. N1IC in T cells overcomes the tolerogenic effect induced by MDSC.

(A) MDSC were isolated from tumors and spleens of mice bearing s.c. 3LL cells for 17 days using anti-Gr1 kits. Then, total RNA was isolated and tested for Notch ligands by Quantitative PCR. Results represent mean ± SD from 4 independent animals and tested in triplicate. ***, P < 0.001. (B) Activated CD3+ T cells were co-cultured at different ratios with tumor-infiltrating MDSC for 48 hours. Then, T cells were negatively isolated using anti-CD11b beads and whole protein extracts harvested and used for detection of Notch-1 and -2 isoforms by western blot. A representative experiment of 3 repeats is shown. (C) Activated T cells co-cultured with MDSC at a 1:1/2 ratio were treated with L-NMMA (500 μM), D-NMMA (500 μM), and NN (200 μM) for 48 hours. Then, extracts were isolated and used as in (B). Representative results are from 3 similar experiments. (D) CD8+ T cells from CD45.2+ N1IC or N1ICf/f mice were adoptively transferred into CD45.1+ congeneic recipients. Following transfer, mice were vaccinated with a mix of dendritic cells (DC) and/or MDSC pulsed with siinfekl, as described in the Methods, and the draining lymph nodes harvested, activated with siinfekl, and tested for the production of IFMγ using ELISpot. Results represent mean ± SD from 2 similar independent experiments. Ns= Non-statistical significance, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.001.

Discussion

This study provides evidence of the suppressive role of the down-regulation of Notch-1 and -2 in T-cell responses in tumors. Also, we show the therapeutic potential of the transgenic expression of N1IC in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as a targeted approach to overcome tumor-induced tolerance and enhance the efficacy of T cell-based cancer immunotherapy.

The effect of Notch in the function of CD4+ T cells has been widely studied; whereas its role in CD8+ T-cell responses remains unclear (8). Our results suggest that Notch-1 and -2, although functionally redundant, play a major role in T-cell proliferation and IFMγ production of CD8+ T cells. Similarly, a decreased proliferation and IFMγ production were also observed in CD4+ T cells conditionally lacking Notch-1 and -2 or treated with blocking antibodies against Notch-1 and Notch-2 (20, 39, 40). Furthermore, we found that expression of N1IC in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells promoted effector responses through amplification of canonical and non-canonical Notch pathways and rendered T cells resistant to tumor-induced tolerance. A similar promotion of T-cell cytotoxicity by Notch signaling was recently confirmed in human CD8+ T cells (32). In addition, signaling through Notch-2 promoted cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells (28), suggesting a similar effect of Notch-1 and -2 in CD8+ T-cell effector responses. In contrast to these results, overexpression of N1IC in CD8+ T cells controlled by CD8α Cre recombinase failed to induce antitumor effects (30). These opposite results could be explained by the distinct tumor models employed or differential effects of the specific promoters regulating Cre recombinase. Indeed, we found that expression of N1IC under CD2-Cre that triggered N1IC expression in immature T cells led to ALL, while N1IC induction through granzyme B-Cre only increased their effector function. Recent results suggested the role of effector memory CD8+ T cells in antitumor responses (41). Our data show that expression of N1IC induced a CD8+ T-cell central memory phenotype characterized by the expression of CD44high CD62L+ CD122+ CD127+. However, the relevance of this phenotype in the antitumor effects observed in N1IC mice remains unknown.

Previous studies tested the therapeutic effect of Notch signaling as a way to increase effector T-cell responses in tumor-bearing hosts. An agonistic antibody against Notch-2 induced antitumor responses and extended survival of tumor-bearing mice (30). A similar effect was induced after over expression of DLL1 in dendritic cells or by using a DLL1- or DLL4-fc fused proteins (30, 31). In contrast, Jagged-2 expression on dendritic cells failed to induce antitumor effects (31), suggesting the preferential effect of specific Notch ligands in the induction of antitumor responses. The interaction of DLL1 and DLL4 and Notch-1 and Notch-2 also played a major role in the development of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)(39). Inhibition of these pathways using blocking antibodies inhibited GVHD development by inducing T-cell anergy (39, 42). However, several concerns have been raised against the use of anti-Notch antibodies or Notch-ligands-fused proteins in therapies due to toxicity and unspecific cellular reactions. Our results suggest an innovative Notch-based therapeutic approach, which could overcome the toxicity and specificity limitations, and enhance efficacy of immunotherapy in cancer and other diseases.

MDSC are considered major mediators of T-cell dysfunction in cancer, chronic infectious diseases, sepsis, trauma, and autoimmunity (43). Our results show the relevance of Notch in immune suppression induced by MDSC. Transgenic expression of N1IC rendered T cells resistant to the tolerogenic effect of MDSC in vivo. This is highly relevant as most therapies blocking MDSC have focused on their direct inhibition rather than rendering the target populations, such as T cells, resistant to MDSC suppression. We found that MDSC blocked Notch expression in T cells through nitric oxide-linked pathways; however, the precise mechanisms of how nitric oxide prevented Notch expression are unknown. Our recent published data suggested the independent role of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in the suppression induced by MDSC (44). However, the effect of these pathways in the regulation of Notch signaling remains unknown. Furthermore, tumor-linked MDSC expressed high levels of Jagged-1 and -2, which were shown to induce suppression of CD8+ T-cell responses (45). Thus, in addition to the inhibition of Notch expression in T cells, MDSC could also trigger negative Notch signals leading to T-cell suppression. The specific modulation of Notch ligands in the function and maturation of MDSC is still unknown. Initial results suggested a potential role of Jagged-1 and DLL1 and low Notch-signaling by Notch phosphorylation in the generation of MDSC (46, 47).

In summary, the use of transgenic-N1IC in activated CD8+ T cells carries the potential to overcome immune suppression in tumors and significantly increase the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Therefore, continuation of this work could enable the design of new therapeutic approaches to reverse T-cell anergy in individuals with cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonna Ellis for her administrative assistance.

Financial support: This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P20GM103501 subproject #3 to P.C.R., NIH-R21CA162133 to P.C.R

Abbreviations

- N1IC

Notch-1 intracellular domain

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- NICD

Notch intracellular active domain

Footnotes

Authorship contributions

Rosa A. Sierra: Planned, performed, and supervised most of the experiments.

Paul Thevenot: Planned and performed experiments.

Patrick L. Raber: Performed experiments.

Yan Cui: Provide advice and reagents for experiments.

Chris Parsons: Provide advice for experiments.

Augusto A. Ochoa: Provide advice for experiments.

Jimena Trillo-Tinoco: Performed experiments Luis Del Valle: Provide advice and reagents for experiments.

Paulo C. Rodriguez: Planned, developed, and analyzed experiments. Wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

The authors do not have conflict of interest to disclose.

Reference List

- 1.Gattinoni L, Powell DJ, Jr., Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:383–93. doi: 10.1038/nri1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced cancer: crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:759–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalos M, June CH. Adoptive T cell transfer for cancer immunotherapy in the era of synthetic biology. Immunity. 2013;39:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:269–281. doi: 10.1038/nri3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gajewski TF, Woo SR, Zha Y, Spaapen R, Zheng Y, Corrales L, et al. Cancer immunotherapy strategies based on overcoming barriers within the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–15. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radtke F, MacDonald HR, Tacchini-Cottier F. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:427–37. doi: 10.1038/nri3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guruharsha KG, Kankel MW, rtavanis-Tsakonas S. The Notch signalling system: recent insights into the complexity of a conserved pathway. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:654–66. doi: 10.1038/nrg3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radtke F, Fasnacht N, MacDonald HR. Notch signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2010;32:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborne BA, Minter LM. Notch signalling during peripheral T-cell activation and differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:64–75. doi: 10.1038/nri1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minter LM, Osborne BA. Canonical and non-canonical Notch signaling in CD4(+) T cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2012;360:99–114. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabher C, von Boehmer H, Look AT. Notch 1 activation in the molecular pathogenesis of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:347–59. doi: 10.1038/nrc1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch U, Radtke F. Mechanisms of T cell development and transformation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:539–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler SH, Chiffoleau E, Xu L, Dalton NM, Burg JM, Wells AD, et al. Notch signaling augments T cell responsiveness by enhancing CD25 expression. J Immunol. 2003;171:2896–903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi I, Minter LM, Telfer J, Demarest RM, Capobianco AJ, Aster JC, et al. Notch signaling mediates G1/S cell-cycle progression in T cells via cyclin D3 and its dependent kinases. Blood. 2009;113:1689–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palaga T, Miele L, Golde TE, Osborne BA. TCR-mediated Notch signaling regulates proliferation and IFN-gamma production in peripheral T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:3019–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bheeshmachar G, Purushotaman D, Sade H, Gunasekharan V, Rangarajan A, Sarin A. Evidence for a role for notch signaling in the cytokine-dependent survival of activated T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:5041–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho OH, Shin HM, Miele L, Golde TE, Fauq A, Minter LM, et al. Notch regulates cytolytic effector function in CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:3380–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auderset F, Schuster S, Coutaz M, Koch U, Desgranges F, Merck E, et al. Redundant Notch1 and Notch2 signaling is necessary for IFNgamma secretion by T helper 1 cells during infection with Leishmania major. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002560. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauma D, Ramirez A, Alvarez K, Rosemblatt M, Bono MR. Notch signalling regulates cytokine production by CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Scand J Immunol. 2012;75:389–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minter LM, Osborne BA. Notch and the survival of regulatory T cells: location is everything! Sci Signal. 2012;5:e31. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amsen D, Antov A, Flavell RA. The different faces of Notch in T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:116–24. doi: 10.1038/nri2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amsen D, Antov A, Jankovic D, Sher A, Radtke F, Souabni A, et al. Direct regulation of Gata3 expression determines the T helper differentiation potential of Notch. Immunity. 2007;27:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu L, Fang TC, Artis D, Shestova O, Pross SE, Maillard I, et al. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1037–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elyaman W, Bassil R, Bradshaw EM, Orent W, Lahoud Y, Zhu B, et al. Notch receptors and Smad3 signaling cooperate in the induction of interleukin-9-producing T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:623–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becher B, Segal BM. T(H)17 cytokines in autoimmune neuro-inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:707–12. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maekawa Y, Minato Y, Ishifune C, Kurihara T, Kitamura A, Kojima H, et al. Notch2 integrates signaling by the transcription factors RBP-J and CREB1 to promote T cell cytotoxicity. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1140–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kijima M, Iwata A, Maekawa Y, Uehara H, Izumi K, Kitamura A, et al. Jagged1 suppresses collagen-induced arthritis by indirectly providing a negative signal in CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:3566–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugimoto K, Maekawa Y, Kitamura A, Nishida J, Koyanagi A, Yagita H, et al. Notch2 signaling is required for potent antitumor immunity in vivo. J Immunol. 2010;184:4673–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y, Lin L, Shanker A, Malhotra A, Yang L, Dikov MM, et al. Resuscitating cancer immunosurveillance: selective stimulation of DLL1-Notch signaling in T cells rescues T-cell function and inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6122–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuijk LM, Verstege MI, Rekers NV, Bruijns SC, Hooijberg E, Roep BO, et al. Notch controls generation and function of human effector CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2013;121:2638–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murtaugh LC, Stanger BZ, Kwan KM, Melton DA. Notch signaling controls multiple steps of pancreatic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14920–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436557100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Sanderson NS, Wawrowsky K, Puntel M, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Kupfer-type immunological synapse characteristics do not predict anti-brain tumor cytolytic T-cell function in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4716–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911587107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez PC, Hernandez CP, Quiceno D, Dubinett SM, Zabaleta J, Ochoa JB, et al. Arginase I in myeloid suppressor cells is induced by COX-2 in lung carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2005;202:931–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, Mesa C, Fernandez A, Dolcetti L, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagaraj S, Gupta K, Pisarev V, Kinarsky L, Sherman S, Kang L, et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat Med. 2007;13:828–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Bronte V. Measurement of myeloid cell immune suppressive activity. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1417s91. Chapter 14:Unit14.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tran IT, Sandy AR, Carulli AJ, Ebens C, Chung J, Shan GT, et al. Blockade of individual Notch ligands and receptors controls graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1590–604. doi: 10.1172/JCI65477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helbig C, Gentek R, Backer RA, de SY, Derks IA, Eldering E, et al. Notch controls the magnitude of T helper cell responses by promoting cellular longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9041–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206044109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Kao C, Banerjee A, Schambach F, Northrop JK, et al. Requirement for T-bet in the aberrant differentiation of unhelped memory CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2015–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandy AR, Chung J, Toubai T, Shan GT, Tran IT, Friedman A, et al. T cell-specific notch inhibition blocks graft-versus-host disease by inducing a hyporesponsive program in alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:5818–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raber PL, Thevenot P, Sierra R, Wyczechowska D, Halle D, Ramirez ME, et al. Subpopulations of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSC) impair T cell responses through independent nitric oxide-related pathways. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2853–64. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kared H, dle-Biassette H, Fois E, Masson A, Bach JF, Chatenoud L, et al. Jagged2-expressing hematopoietic progenitors promote regulatory T cell expansion in the periphery through notch signaling. Immunity. 2006;25:823–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu H, Zhou J, Cheng P, Ramachandran I, Nefedova Y, Gabrilovich DI. Regulation of dendritic cell differentiation in bone marrow during emergency myelopoiesis. J Immunol. 2013;191:1916–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng P, Kumar V, Liu H, Youn JI, Fishman M, Sherman S, et al. Effects of notch signaling on regulation of myeloid cell differentiation in cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:141–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.