Abstract

Objective

Disease-specific reductions in patient productivity can lead to substantial economic losses to society. The purpose of this study was to: 1) define the annual productivity cost for a patient with refractory chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and 2) evaluate the relationship between degree of productivity cost and CRS-specific characteristics.

Study Design

Prospective, multi-institutional, observational cohort study.

Methods

The human capital approach was used to define productivity costs. Annual absenteeism, presenteeism, and lost leisure time was quantified to define annual lost productive time (LPT). LPT was monetized using the annual daily wage rates obtained from the 2012 US National Census and the 2013 US Department of Labor statistics.

Results

A total of 55 patients with refractory CRS were enrolled. The mean work days lost related to absenteeism and presenteeism was 24.6 and 38.8 days per year, respectively. A total of 21.2 household days were lost per year related to daily sinus care requirements. The overall annual productivity cost was $10,077.07 per patient with refractory CRS. Productivity costs increased with worsening disease-specific QoL (r=0.440; p=0.001).

Conclusion

Results from this study have demonstrated that the annual productivity cost associated with refractory CRS is $10,077.07 per patient. This substantial cost to society provides a strong incentive to optimize current treatment protocols and continue evaluating novel clinical interventions to reduce this cost.

Keywords: Chronic rhinosinusitis, Sinusitis, Productivity, Cost, Economic, Indirect cost, Absenteeism, Presenteeism

Introduction

Defining accurate disease-specific costs are important for the generation of appropriate economic evaluations. A societal perspective to cost estimation requires the incorporation of both direct and indirect costs. Indirect costs primarily pertain to productivity losses experienced by a patient and are commonly caused by reduced work performance (ie. Presenteeism) and missed time from work (ie. Absenteeism) due to a health condition. Several common chronic conditions, such as asthma1, migraine2,3, and diabetes4 have defined productivity costs and the outcomes from these studies have improved their disease-specific societal cost estimates.

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common chronic inflammatory disease with detrimental health effects including reduced quality of life (QoL)5, poor sleep6,7, fatigue8, acute infections9, and bodily pain10. These negative sequelae can predispose CRS patients to have impaired work place productivity in the form of both presenteeism and absenteeism. To accurately define the societal cost of CRS, it is important to define the degree of lost productivity and then quantify the associated productivity costs.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the impact of refractory CRS on patient productivity and define the annual productivity cost associated with this disease. Secondary objectives include evaluating the relationship between CRS-specific characteristics and degree of productivity costs.

Methods

The human capital approach was used to define productivity costs. Productivity data was collected prospectively in multi-institutional, international (USA and Canada), observational study (Clinicaltrials# NCT00799097; NIH: R01 DC005805). Inclusion criteria was a diagnosis of CRS based on AAOHNS guidelines (which included objective confirmation of inflammation on either endoscopy or CT imaging)11 and failed initial medical therapy as defined by a minimum 3 months of topical nasal steroid therapy, a minimum 7 days of systemic corticosteroid therapy (prednisone 30mg PO once daily), and 2 weeks of broad spectrum antibiotic. We considered this patient cohort to have refractory CRS due to the persistent symptoms despite the defined initial medical therapy protocol.

In addition to productivity data, we measured disease-specific quality of life (QoL) using the Sinonasal Outcomes Test (SNOT-22)12 and endoscopy scores using the Lund-Kennedy grading system13. Patients were enrolled at four tertiary level rhinology clinics (Medical University of South Carolina, University of Calgary, Stanford University, and Oregon Health Science University). All questionnaires are validated for the English language and were administered by a trained research coordinator to ensure accuracy of reported data.

Measurement of Lost Productive Time

For this study, Lost Productive Time (LPT) was defined as the per-person work days lost due to refractory CRS. We assumed the following average paid work time per patient: 8 hours per day, 5 days per week with 4 weeks of vacation per year. This provided a total of 48 paid work weeks and a total of 240 paid work days per year.

Presenteeism was measured based on the Quantity and Quality Questionnaire14,15. Patients were asked on average the degree (%) of reduced daily work performance due to CRS. Healthy baseline performance was assumed to be 100% productivity. The annual number of work days missed due to CRS-related presenteeism was calculated using the following formula: P = (E – A)*p; where P is the number of missed work days due to presenteeism, E is the expected number of annual work days (ie. 240), A is the work days missed due to absenteeism, and p is the % reduced performance at work16.

Based on current recall recommendations, absenteeism was quantified by asking both the number of full work days missed and the number of work hours missed due to CRS in the last 3 months16-18. Total annual work days lost was calculated by summing the work days lost from both presenteeism and absenteeism due to CRS.

Household productivity loss was calculated by asking patients how much time is used at home to care for their sinuses per day. It was assumed the potential household productivity/leisure time available for weekdays is 7 hours per day (5pm to 12am) and on weekdays it is 15 hours per day (9am to 12am) for 52 weekends per year. Therefore, 7 household hours lost per weekday or 15 household hours lost per weekend would equal one household work day lost. Household productivity is reported separately from paid work days missed since it has a different monetary valuation.

Monetization of Lost Productive Time

To accurately reflect the productivity cost to society, we used a societal wage rate equal to the median annual individual income from the 2012 US National Census19. The median annual individual income was converted into a mean daily income rate by assuming 48 work weeks per year, 40 hours per week and 8 hours per day. Household productivity was valued by assuming it was equal to the hourly wage of a housekeeper. The 2013 United States Department of Labor statistics were used to define the average wage rate for a housekeeper20.

Relationship between Productivity Costs and CRS-related Characteristics

Productivity costs were calculated for each patient. This enabled us to statistically evaluate the relationship of productivity costs to several CRS-specific characteristics including patient demographics, disease subtypes, comorbidities, and degree of QoL reduction. Descriptive statistics were calculated using SPSS v.22 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk NY). Correlations between productivity costs, age, and SNOT-22 scores were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Differences in productivity costs between comorbid characteristics were assessed using the Mann Whitney U test for nonparametric distributions.

Results

Subject characteristics

In this study we obtained baseline productivity costs and disease-specific QoL on a total of 55 patients with refractory CRS. The average subject age was 43.1 (14.9) years old (range: 19-75) with a higher proportion of females (n=29; 52.7%) than males. Comorbid characteristics included: 12 subjects with nasal polyps (21.8%) and 17 subjects with asthma (30.9%). The mean baseline SNOT-22 score (range: 4 - 106) was 52.8(21.6) while the mean endoscopy score (range: 0 - 14) was 5.4(3.6).

Refractory CRS-related Lost Productive Time

The mean annual absenteeism LPT was calculated to be 24.6 days per patient with refractory CRS (Table 1). Patients with refractory CRS reported a mean daily reduction in work performance of 18%. The mean annual presenteeism LPT was then calculated (P = (240 − 24.6)*0.18) to be 38.8 work days missed per patient (Table 1). The overall annual LPT from both absenteeism and presenteeism was then calculated to be 63.4 work days missed per patient with refractory CRS.

Table 1.

Summary of refractory CRS-related LPT outcomes

| Productivity Outcome | Mean | Range (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Paid Work Absenteeism | ||

| Annual number of full work days missed | 18.1 | 0-256 (8.4) |

| Annual number of work hours missed | 51.8 (6.5 full days) | 0-200 (27.1) |

| Annual absenteeism LPT (days) | 24.6 | |

| Paid Work Presenteeism | ||

| Daily reduction in work performance (%) | 18 | 0-40% (13) |

| Annual presenteeism LPT (days) | 38.8 | |

| Household Absenteeism | ||

| Hours per day spent caring for CRS | 0.48 (29 min) | 0.02-2 (0.43) |

| Annual household LPT (days) | 21.2 | |

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; LPT, lost productive time

Patients with refractory CRS reported a mean of 29 minutes per day caring for their sinus disease which is 0.48 hours per day. Using the weekday and weekend household/leisure productivity assumptions outlined in the methods above, the mean sinus care time results in one household day lost 14.6 weekdays (7/0.48) and 31.3 weekend days (15/0.48). This creates a mean of 21.2 household days lost per year (Table 1).

Monetized Lost Productive Time

According to the 2012 US National Census, the median annual US income is $30,853 which produces a mean daily income of $128.5519. This value was used to value the paid work LPT. Using the 2013 United States Department of Labor statistics20, the mean overall hourly wage rate for a housekeeper is $10.49 which produced a daily household monetized LPT of $90.91.

Overall Productivity Cost

The productivity costs related to paid work LPT was $8,150.07 per year and the costs related to household LPT was $1,927 per year. This produced an overall annual productivity cost of $10,077.07 per patient with refractory CRS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of CRS-related productivity costs

| Mean | |

|---|---|

| Annual paid work LPT (Absenteeism + Presenteeism) | 63.4 days |

| Monetized daily paid work LPT | $128.55 |

| Annual paid work productivity cost | $8,150.07 |

| Annual household LPT | 21.2 days |

| Monetized daily household LPT | $90.91 |

| Annual household work productivity cost | $1,927.29 |

| Annual productivity cost per patient with refractory CRS | $10,077.07 |

LPT, lost productive time; CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis

Effect of CRS Characteristics on Productivity Costs

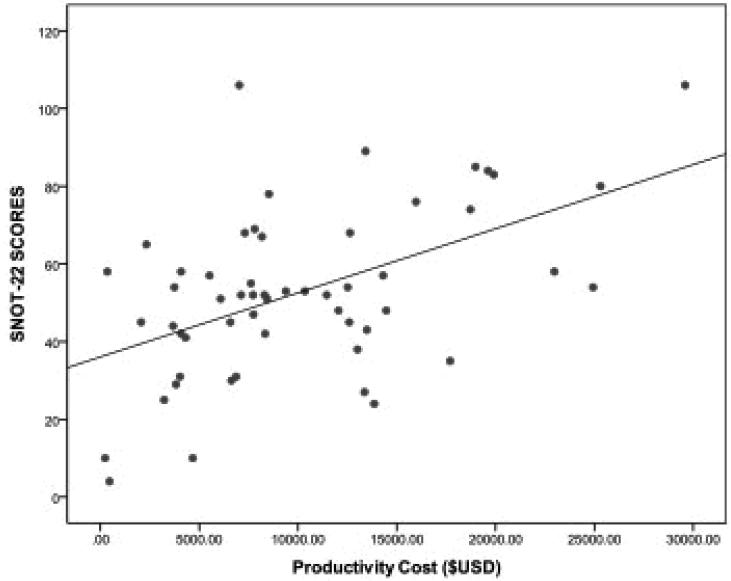

When evaluating the effect of CRS characteristics on the degree of productivity costs, there was no association between CRS with/without polyposis (p=0.132) and CRS with/without asthma (p=0.244). There was a significant correlation between productivity cost and degree of disease-specific QoL impairment (rs=0.440; p=0.001)(Figure 1). This suggests that worsening QoL results in increased productivity costs. There was a significant correlation between age and productivity costs (rs= −0.315; p=0.019). As expected, the age groups with highest income potential (ages 30 to 50 years) resulted in the highest productivity costs. There was a trend of increasing productivity cost with worsening endoscopy score that failed to reach statistical significance (rs= 0.263; p=0.054). Table 3 summarizes the effects of CRS characteristics on productivity costs.

Figure 1.

Relationship between disease-specific quality of life and productivity costs

Table 3.

Summary of CRS-subgroup productivity costs

| CRS subgroups | Mean Annual Productivity Cost (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort (n=55) | $10,077.07 ($6,714) | |

| CRS w/ NP (n=12) | $7,182 ($3,916) | p=0.132 |

| CRS s/ NP (n=43) | $10,961 ($7,123) | |

| CRS w/ Asthma (n=17) | $8,444 ($5,964) | p=0.244 |

| CRS s/ Asthma (n=38) | $10,894 ($6,964) | |

| SNOT-22 Scores: | ||

| 0-20 (n=3) | $1,790 ($2,501) | rs= 0.440; p=0.001 |

| 21-40 (n=9) | $9,167 ($5,352) | |

| 41-60 (n=28) | $9,082 ($5,629) | |

| 61-80 (n=9) | $11,865 ($7,056) | |

| 81-110 (n=6) | $18,094 ($7,524) | |

| Endoscopy Scores: | ||

| 0-4 (n=27) | $8,782 ($6,191) | rs= 0.263; p=0.054 |

| 5-8 (n=17) | $10,455 ($7,073) | |

| 9+ (n=10) | $12,820 ($7,415) | |

| Age (years): | ||

| 18-29 (n=12) | $10,637 ($7,163) | rs= –0.315; p=0.019 |

| 30-39 (n=12) | $13,140 ($6,806) | |

| 40-49 (n=12) | $13,313 ($6,830) | |

| 50-59 (n=11) | $6,992 ($4,568) | |

| 60+ (n=8) | $4,439 ($2,309) | |

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; SD, standard deviation; SNOT, sinonasal outcome test; n, number

Discussion

This prospective, multi-institutional, observational study evaluated 55 patients with refractory CRS and determined that the annual productivity cost was $10,077.07 per patient. This estimate included both presenteeism and absenteeism from paid work as well as lost household/leisure time related to daily sinus care requirements. The degree of productivity cost appeared to be associated with the level of disease-specific QoL since costs increased with worsening SNOT-22 scores. Although this was a pilot study, it provides a first glimpse into the substantial economic burden of refractory CRS on societal productivity.

Productivity costs represent a major economic loss to society as there is an estimated $260 billion lost in output every year in the US21. It is recommended that the societal perspective be the goal for economic evaluations since it would optimize the policy makers ability to make appropriately informed decisions regarding efficient health care resource allocation22. In order to assume a societal perspective, researchers must use accurately defined indirect and direct costs. Although direct medical costs of CRS have been investigated and defined23-25, the indirect costs (i.e. productivity costs) have not been thoroughly quantified and this was the focus of our study. Other common chronic diseases such as diabetes, asthma, and migraine have accurately defined their indirect costs1,2,4 and this has lead to accurate economic evaluations performed from the perspective of society. For example, a recent study by Pershing et al. evaluated the cost-effectiveness of treatment for macular edema from the societal perspective. The results demonstrated that the most cost-effective option for society was vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor injections combined with laser since it provided an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of $12,410 which is below the commonly excepted willingness to pay of $50,00026. Another recent study by Wang et al. performed an economic evaluation evaluating the management of pediatric patients with mild to moderate asthma from the perspective of the US government and society. Results demonstrated that low dose fluticasone was a dominant cost effective intervention compared to montelukast27. These economic evaluations from the societal perspective were possible because the indirect costs for each disease were defined in earlier studies.

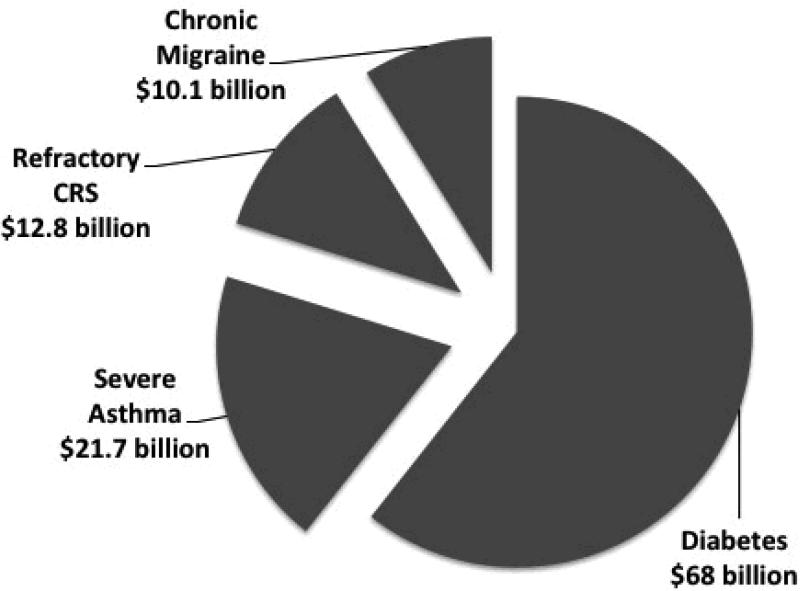

It is generally accepted that productivity costs are several times greater then direct medical costs and therefore should be considered an important economic outcome when evaluating a clinical intervention28. This manuscript referred to refractory CRS as a subset patients with CRS who have persistent symptoms despite extensive medical therapy which included 3 months of topical corticosteroid therapy and courses of systemic corticosteroid and systemic antibiotics. Although it is a very challenging to provide an exact prevalence estimate for this patient cohort, using a conservative assumption of 0.5% (ie. 5% of the overall 10% CRS population prevalence), the overall societal productivity cost would be $12.8 billion (Figure 2). This is approximately a 50% increase of the estimated $8.6 billion attributed to direct medical costs of CRS24. Therefore, a clinical intervention that provides a 10% improvement in productivity losses in patients with refractory CRS would equate to over a $1.2 billion savings for society.

Figure 2.

Overall annual societal productivity costs (adjusted for inflation) of four common chronic diseases after taking disease prevalence into account1,2,4

Despite the tremendous negative impact of lost productivity on society, it remains controversial whether or not to include productivity costs in economic evaluations. Inclusion of productivity costs can significantly skew the outcomes of an economic evaluation and are thought to be an inappropriate method to increase the cost-effectiveness of an intervention. Furthermore, the inclusion of productivity costs are thought to result in double-counting since impaired productivity is thought to be unconsciously included in the patients QoL reporting22. In order to address the controversy, it is recommended that productivity loss first be reported as quantities such as number of work days lost and then valued based on a monetary amount such as a wage rate22. Since policy makers require several different economic perspectives during the decision making process for resource allocation, productivity costs should be reported separately from direct health care costs in order to separate the societal cost from health care cost.

A study by Cisternas et al. evaluated the economic burden of asthma and determined that there was a relationship between the annual productivity cost and patient-reported severity of asthma1. The overall annual productivity costs associated with mild, moderate and severe asthma were $582, $1,488, and $5,846, respectively. The results from our study demonstrated a similar finding as productivity costs were correlated to the level of disease-specific QoL impairment (r=0.440; p=0.001). CRS patients with SNOT-22 scores between 0-20 and 20-40 had annual productivity costs of $1,790 and $9,167 compared to those with scores between 60-80 and 80+ which had annual costs of $11,865 and $18,094, respectively. Furthermore, this study is consistent with other studies whereby patients between the ages of 30 to 50 resulted in the highest productivity costs2,4.

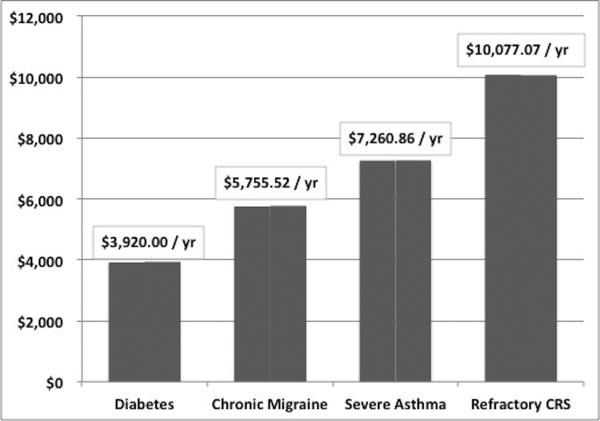

The annual productivity cost of $10,077.07 per patient with refractory CRS reported in this study is higher than the reported annual productivity cost of other common chronic diseases (Figure 3). Furthermore, patients in our study averaged an annual absenteeism of 24.6 work days which is much higher than an earlier study by Bhattacharyya which reported an average annual absenteeism of 5.7 work days23. One potential reason for these findings is that all patients were prospectively enrolled at tertiary level centers and thus had very accurate diagnoses of CRS as compared to other studies identified patients using national databases which rely on the accuracy of physician coding and thus likely included patients without an accurate diagnosis of CRS. Furthermore, patients enrolled in this study had severe reductions in baseline QoL (mean SNOT-22 was 52.8) and had failed extensive prior medical therapy and were considered to have refractory CRS as compared to other studies which may have included patients without refractory CRS. Therefore, patients in this study are likely comprised of those with the largest productivity costs. Another potential reason for our findings is that we included the cost of losing household/leisure time which several of the other studies failed to incorporate. Even if we exclude the costs of household/leisure time, the annual productivity cost of $8,150 per patient with refractory CRS is still greater than other diseases, such as asthma, diabetes and migraine. Lastly, this was a pilot study evaluating only 55 patients and therefore we are continuing to collect productivity data in a prospective study (Clinicaltrials# NCT01332136) to further refine the outcomes.

Figure 3.

Annual productivity cost per patient (adjusted for inflation) of four common chronic diseases1,2,4

Another factor to consider when interpreting these results is that the overall productivity costs reported in this study were specific to patients who had failed extensive medical therapy and thus represent a small cohort of the overall CRS population. Therefore, the overall productivity cost in this study cannot be applied to all patients with CRS and should be limited to those with refractory CRS. Lastly, there is a potential risk of recall bias when asking patients to quantify absenteeism. Although potential bias is present in any study design that asks patients to recall past events, we feel this risk has been minimized by following the current recall recommendations of 3 months16-18. Despite these factors, the study is strengthened by its prospective, multi-institutional, international study design and provides the first insight into the large productivity cost to society associated with refractory CRS.

Conclusion

Patients with refractory CRS suffer several negative health consequences including reduced QoL, poor sleep, and increased bodily pain. These disease-related effects can lead to work absences, reduced work performance, and lost leisure household time. Results from this prospective study have demonstrated that the annual productivity cost associated with refractory CRS is $10,077.07 per patient. This substantial cost to society provides a strong incentive to optimize current treatment protocols and continue evaluating novel clinical interventions to reduce this cost.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institutes of Health had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript or decision to submit it for publication.

Funding/Support: Dr. T. L. Smith, Dr. Z. M. Soler, and J. Mace are supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH: R01 DC005805).

ZMS: Grant support from the NIH/NIDCD

JCM: Grant support from the NIH/NIDCD

RJS: Consultant for BrainLAB, Olympus, United Allergy; Grant support from Medtronic, Arthrocare, Intersect ENT, Optinose, NeilMed.

PHH: Consultant for Intersect ENT, Medtronic, Sinuwave, 3NT; Grant support from Xoran

TLS: Consultant for Intersect ENT Inc. (Menlo Park, CA). Grant support from NIH/NIDCD

Footnotes

Potential Conflict(s) of Interest:

LR: None

References

- 1.Cisternas MG, Blanc PD, Yen IH, et al. A comprehensive study of the direct and indirect costs of adult asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2003;111:1212–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serrano D, Manack AN, Reed ML, Buse DC, Varon SF, Lipton RB. Cost and predictors of lost productive time in chronic migraine and episodic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2013;16:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munakata J, Hazard E, Serrano D, et al. Economic burden of transformed migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2009;49:498–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012 Diabetes care. 2013;36:1033–46. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudmik L, Smith TL. Quality of life in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Current allergy and asthma reports. 2011;11:247–52. doi: 10.1007/s11882-010-0175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alt JA, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis and sleep: a contemporary review. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2013;3:941–9. doi: 10.1002/alr.21217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alt JA, Smith TL, Mace JC, Soler ZM. Sleep quality and disease severity in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2364–70. doi: 10.1002/lary.24040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soler ZM, Mace J, Smith TL. Symptom-based presentation of chronic rhinosinusitis and symptom-specific outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery. American journal of rhinology. 2008;22:297–301. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rank MA, Wollan P, Kita H, Yawn BP. Acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis occur in a distinct seasonal pattern. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010;126:168–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chester AC, Sindwani R, Smith TL, Bhattacharyya N. Systematic review of change in bodily pain after sinus surgery. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2008;139:759–65. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007;137:S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, Lund VJ, Browne JP. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2009;34:447–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;117:S35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwer WB, Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FF. Productivity losses without absence: measurement validation and empirical evidence. Health Policy. 1999;48:13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koopmanschap MA. PRODISQ: a modular questionnaire on productivity and disease for economic evaluation studies. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2005;5:23–8. doi: 10.1586/14737167.5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Bansback N, Anis AH. Measuring and valuing productivity loss due to poor health: A critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revicki DA, Irwin D, Reblando J, Simon GE. The accuracy of self-reported disability days. Medical care. 1994;32:401–4. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199404000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severens JL, Mulder J, Laheij RJ, Verbeek AL. Precision and accuracy in measuring absence from work as a basis for calculating productivity costs in The Netherlands. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:243–9. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US National Census: Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2012 2013 Accessed at http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p60-245.pdf.)

- 20.US Department of Labor: Occupational Employment Statistics 2013 Accessed at http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes372012.htm.)

- 21.Davis K, Collins SR, Doty MM, Ho A, Holmgren A. Health and productivity among U.S. workers. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2005:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharyya N. Contemporary assessment of the disease burden of sinusitis. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2009;23:392–5. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharyya N. Incremental health care utilization and expenditures for chronic rhinosinusitis in the United States. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2011;120:423–7. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharyya N, Orlandi RR, Grebner J, Martinson M. Cost burden of chronic rhinosinusitis: a claims-based study. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2011;144:440–5. doi: 10.1177/0194599810391852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cost-Effectiveness of Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema. ANn Intern Med. 2014;160 doi: 10.7326/M13-0768. S. P, E.A. E, B. M, D.K. O, J.D. G-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Hollenbeak CS, Mauger DT, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fluticasone versus montelukast in children with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma in the Pediatric Asthma Controller Trial. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;127:161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.035. 6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, Hawkins K, Wang S, Lynch W. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting U.S. employers. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine / American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2004;46:398–412. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000121151.40413.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]