Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the potential efficacy of buspirone as a relapse-prevention treatment for cocaine dependence.

Method

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week pilot trial conducted at six clinical sites between August 2012 and June 2013. Adult crack cocaine users meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for current cocaine dependence scheduled to be in inpatient/residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment for 12–19 days when randomized, and planning to enroll in local outpatient treatment through the end of the active treatment phase were randomized to buspirone titrated to 60 mg/day (n=35) or to placebo (n=27). All participants received psychosocial treatment as usually provided by the SUD treatment programs in which they were enrolled. Outcome measures included maximum days of continuous cocaine abstinence (primary), proportion of cocaine use days, and days-to-first-cocaine-use during the outpatient treatment phase (study weeks 4–15) as assessed by self-report and urine drug screens.

Results

There were no significant treatment effects on maximum continuous days of cocaine abstinence or days to first cocaine use. In the females (n=23), there was a significant treatment-by-time interaction effect (X2(1)=6.06, p=.01), reflecting an increase in cocaine use by the buspirone, relative to placebo, participants early in the outpatient treatment phase. A similar effect was not detected in the male participants (n=39; X2(1)=0.14, p=.70).

Conclusions

The results suggest that buspirone is unlikely to have a beneficial effect on preventing relapse to cocaine use and that buspirone for cocaine-dependent women may worsen their cocaine-use outcomes.

Trial Registration

Clinical Trials.gov http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Identifier: NCT01641159

Keywords: cocaine, buspirone, relapse-prevention, clinical trial, gender

INTRODUCTION

In 2010, over one million people in the U.S. were abusing or dependent on cocaine1 and in Europe cocaine use has increased significantly in recent years.2 Though psychosocial interventions for cocaine dependence can help, treatment dropout followed by relapse to cocaine use is high. Despite extensive work, there still is no FDA-approved treatment for cocaine dependence.3 Pre-clinical research has found that dopamine D3 receptor antagonists can reduce the rewarding effects of cocaine and reinstatement of cocaine seeking.4–6 In addition, imaging research suggests that dopamine D3 receptors may be upregulated in stimulant abusers.7 Buspirone is an FDA-approved treatment for generalized anxiety disorder with little abuse potential8 and a well-established safety profile.9 Buspirone has long been established to be a 5HT1A agonist,8 but in more recent years has been determined to be a dopamine D310, 11 and D4 antagonist11 as well. Buspirone has been found to significantly decrease cocaine-cue reinstatement in rats12 and both acute11, 13 and chronic14 buspirone have been found to decrease cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys.

Based on the pre-clinical data showing buspirone’s ability to decrease cocaine reinstatement and self-administration, combined with its favorable safety profile, a clinical trial, “A Randomized Controlled Evaluation of Buspirone for Relapse-Prevention in Adults with Cocaine Dependence (BRAC)”, was conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) to test the efficacy of buspirone as a cocaine-dependence treatment. Prior research suggests that stimulant-dependent patients vary substantially in their response to dopaminergic agents15 and, thus, testing for subgroups for whom buspirone might be differentially effective was planned for in the trial.16 One subgroup of interest in this regard is gender given evidence that gender plays a significant role in dopaminergic function and response to dopaminergic agents.17–23 Specific to cocaine, research has found that male monkeys who become dominant have an increase in dopamine D2/D3 receptors and evidence less vulnerability to the reinforcing effects of cocaine while female monkeys who become dominant also have an increase in dopamine D2/D3 receptors but evidence more vulnerability to cocaine’s reinforcing effects.24

As described elsewhere,16 BRAC was designed to be a two-stage process in which a pilot trial would first be completed to obtain information needed to address important operational aspects critical to the design of the full-scale clinical trial (e.g., medication tolerability, adherence, missing data rates, eligibility criteria, etc.). The results from the pilot, including an evaluation of gender effects, are reported in the present paper.

METHODS

Study Design

BRAC was a 16-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, intent-to-treat (ITT) trial. Dose titration was completed in an inpatient/residential setting which allowed an evaluation of buspirone as a relapse-prevention treatment, and based on the potential relapse rate of 65%–72%,25–27 also of its ability to curtail on-going cocaine use. Eligible participants were randomized to buspirone or matching placebo and scheduled to receive study medication and to attend two research visits per week throughout the active treatment phase, which began with randomization and ended on day 7 of study week 15. A single visit was scheduled in week 16 to complete retrospective data for week 15. The trial was conducted at six substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs between August 2012 and June 2013. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT01641159).

Participants

Recruitment was primarily from patients seeking inpatient/residential treatment at a participating site; secondary recruitment methods included advertising and direct community promotions, such as networking with community professionals. Eligible participants were adults scheduled to be in inpatient/residential SUD treatment for 12–19 days when randomized, and planning to enroll in local outpatient treatment through the end of the active treatment phase. Participants were required to meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for current cocaine-dependence, to have used crack cocaine a minimum of four times in the 28 days prior to inpatient/residential admission, and to report that their typical pattern of use was at least once a week. Study eligibility was limited to crack cocaine users in the interest of increasing sample homogeneity. Exclusion criteria included a medical or psychiatric condition potentially making participation unsafe, taking psychotropic medication or a medication with which buspirone could have a potentially dangerous interaction, and meeting criteria for current opioid dependence; for women, pregnancy, breastfeeding, or unwillingness to use adequate birth control. All participants were given a thorough explanation of the study and signed an informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating sites.

Procedures

The small sample size for this pilot trial necessitated selecting a single dose of buspirone to be evaluated; the dose evaluated, 60 mg, is the highest FDA-approved dose for treating generalized anxiety disorder. Participants were randomized to buspirone (60 mg per day) or matching placebo in a 1:1 ratio stratified by site and baseline cocaine use frequency (<10 days or ≥ 10 days in the 28 days prior to inpatient/residential admission). Dose escalation was completed over a 10-day period under observation on an inpatient/residential unit in daily divided doses starting with 10 mg on study days 1–3, 20 mg on study days 4–6, 40 mg on study days 7–9 and 60 mg on day 10. Participants who were unable to reach the 60 mg dose or needed to be reduced from 60 mg due to tolerability were maintained on 15 mg, 30 mg, or 45 mg, whichever was the highest dose tolerated. All participants received psychosocial treatment as usually provided by the inpatient/residential and outpatient programs in which they are enrolled (i.e., treatment as usual (TAU)). For the inpatient/residential phase, the minimum allowable TAU was at least one therapeutic activity daily (including milieu therapy) for 12 – 19 days. For the participants’ post-discharge treatment, the minimum allowable TAU was at least one hour of individual or group therapeutic activity per week through study week 15.

During the 15-week treatment phase, participants were scheduled to attend two research visits per week for efficacy and safety assessments. Participants were reimbursed for transportation, inconvenience, and time; a participant attending all 31 post-randomization research visits earned $955. To help assure good medication adherence with buspirone’s required twice daily dosing, all participants could also earn monetary rewards through contingency management (CM) for opening their medication bottle within six hours of a prescribed dose time (i.e., three hours before or after the dose was to be taken). The Med-ic eCAP system (Information Mediary Corporation, Ottawa, Ontario), which is a medication bottle with a microchip that records the times and dates of bottle opening, was used to track medication bottle openings. The CM plan involved a relatively quick escalation of reinforcement earnings as a strategy to promote consistent opening of the medication bottle, with resets to initial reinforcement values for failing to open the bottle as scheduled. A participant who was fully adherent throughout the 15-week active treatment phase could earn a total of $798.50. Reinforcements were provided in the form of retail gift cards (minimum $5 value), with the provision of cash for reinforcements less than $5. The buspirone and placebo participants earned an average of $453.10 (SD=187.81) and $427.40 (SD=209.62), respectively.

Measures

The primary outcome was the maximum days of continuous cocaine abstinence during the outpatient treatment phase (e.g., study weeks 4–15), as assessed by UDS and self-report. A rapid UDS system that screened for cocaine, methamphetamine, amphetamine, opioids, benzodiazepines, and marijuana was used to analyze the urine samples (Branan Medical Corporation, Irvine, California). To avoid falsification, urine samples were collected using temperature monitoring and the validity of urine samples was checked with a commercially available adulterant test. Self-report of substance use was assessed using the Timeline Follow-back (TLFB) method,28 which is a widely employed and well-validated method. Cocaine abstinence was determined by aggregating TLFB and UDS results into a single binary daily composite use indicator. More specifically, an algorithm was developed to combine UDS and TLFB for classifying each day and follows the general principle that a UDS covers a four day look-back period spanning days −3 to 0, where day 0 is when the urine is donated. A positive UDS for which the associated TLFB reports are negative results in “correcting” TLFB days to be cocaine use days. Assumptions are also required for assigning missing UDS dates in scenarios when a UDS is missing. Details on the rules for assigning a day of collection for missing UDS and for combining TLFB and UDS that accounts for missing UDS results has been published elsewhere.16

Secondary outcomes included proportion of cocaine-use days and days to first cocaine use as assessed by UDS and TLFB during the outpatient treatment phase. Safety was assessed through adverse event (AE) reporting and suicide risk assessments. Medication adherence measures included pill counts, participant self-reported adherence, and Med-ic eCAP data. Finally, a biological measure of adherence was obtained for participants in the buspirone arm. Specifically, urine samples were collected weekly during the treatment period and shipped to the University of California San Francisco School of Pharmacy Drug Studies Unit, Analytical Division for analysis. The samples from the buspirone group were assayed for the buspirone metabolite 1-pyrimidinylpiperazine (1-PP) using a liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry method.

Data Analysis

All analyses were completed on the ITT sample using SAS, Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Statistical tests were conducted at a 5% Type I error rate (two-sided) for all measures. The overall rate of missed visits was only 4.4%. Missing data for the primary outcome and days-to-first use variables were imputed as being positive for cocaine use while missing data for the proportion of cocaine use days ignored missing data. The primary outcome variable (maximum days of continuous cocaine abstinence) was tested for a treatment effect using a gamma generalized linear regression. Daily composite cocaine use indicators were tested for treatment and treatment-by-time effects using a logistic generalized mixed model regression. For graphs of daily composite cocaine use, daily percentages were pooled into weekly percentages to improve the clarity of presentation. Days-to-first-cocaine-use was tested for a treatment effect using a Cox Proportional Hazards regression. The days-to-first-use survival graphs display the by-treatment survival probability distributions as estimated using Kaplan-Meier calculations on raw data. For each outcome, the respective regression was performed using all ITT participants, and then repeated using female ITT participants, and using male ITT participants. All regressions used baseline proportion of self-reported cocaine use days as a covariate.

RESULTS

Participants and Disposition

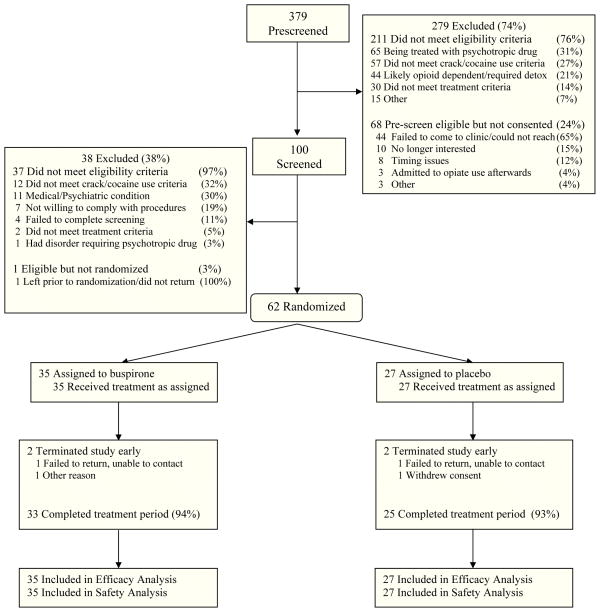

As shown in Figure 1, 379 candidates were pre-screened, 100 were consented and screened, and 62 were randomized to buspirone (n=35) or placebo (n=27). Approximately 94% of participants completed the 15-week active treatment period, with no group differences on completion rate or reasons for non-completion. No participant discontinued the study due to an AE. Demographic and baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between groups for the sample as a whole or within gender subgroup. The sample was approximately 63% male and 73% African American, and participants were 46 years of age on average (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Participant Disposition

Table 1.

Participant demographic and baseline characteristics as a function of treatment group and gender

| All (n=62) | Female (n=23) | Male (n=39) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Buspirone (n=35) | Placebo (n=27) | Total (n=62) | Buspirone (n=11) | Placebo (n=12) | Total (n=23) | Buspirone (n=24) | Placebo (n=15) | Total (n=39) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 44.4 (7.6) | 47.3 (6.6) | 45.6 (7.3) | 41.5 (8.0) | 46.8 (5.8) | 44.3 (7.3) | 45.7 (7.1) | 47.7 (7.3) | 46.5 (7.2) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 24 (68.6%) | 15 (55.6%) | 39 (62.9%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||||

| African-American | 26 (74.3%) | 19 (70.4%) | 45 (72.6%) | 8 (72.7%) | 10 (83.3%) | 18 (78.3%) | 18 (75.0%) | 9 (60.0%) | 27 (69.2%) |

| Caucasian | 8 (22.9%) | 6 (22.2%) | 14 (22.6%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (20.8%) | 5 (33.3%) | 10 (25.6%) |

| Other/mixed | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (7.4%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (5.1%) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |||||||||

| Married | 3 (8.6%) | 5 (18.5%) | 8 (12.9%) | 2 (18.2%) | 1 (8.3%) | 3 (13.0%) | 1 (4.2%) | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (12.8%) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 15 (42.9%) | 5 (18.5%) | 20 (32.3%) | 6 (54.5%) | 3 (25.0%) | 9 (39.1%) | 9 (37.5%) | 2 (13.3%) | 11 (28.2%) |

| Never Married | 17 (48.6%) | 17 (63.0%) | 34 (54.8%) | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | 11 (47.8%) | 14 (58.3%) | 9 (60.0%) | 23 (59.0%) |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 11.5 (2.0) | 11.8 (1.4) | 11.6 (1.8) | 10.6 (2.2) | 11.6 (1.8) | 11.1 (2.0) | 11.9 (1.9) | 12.0 (1.1) | 11.9 (1.6) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||||||||

| Full-time | 8 (22.9%) | 6 (22.2%) | 14 (22.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (4.3%) | 8 (33.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 13 (33.3%) |

| Part-time | 7 (20.0%) | 8 (29.6%) | 15 (24.2%) | 3 (27.3%) | 3 (25.0%) | 6 (26.1%) | 4 (16.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 9 (23.1%) |

| Other | 20 (57.1%) | 13 (48.1%) | 33 (53.2%) | 8 (72.7%) | 8 (66.7%) | 16 (69.6%) | 12 (50.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 17 (43.6%) |

| Days/cocaine use 28 days pre-admission | 16.4 (8.0) | 14.4 (7.1) | 15.5 (7.6) | 18.6 (8.4) | 16.1 (6.5) | 17.3 (7.4) | 15.4 (7.8) | 13.1 (7.4) | 14.5 (7.6) |

Notes. Where not specifically indicated, numbers represent means (standard deviations).

Medication Adherence

Medication adherence and tolerability did not differ significantly between treatment groups for the sample as a whole or within gender subgroup (Table 2). Study participants self-reported taking an average of 90% of the prescribed pills over the course of the study, and participants took, on average, 95% of pills dispensed based on pill count. Based on the Med-ic eCAP data, an average of 85% of the scheduled twice-daily bottle openings occurred across the study participants. The overall rate of urines positive for 1-PP in the buspirone group was 81.5% on average across study participants over all study weeks (Table 2). During the first 7 weeks of the trial, an average of 93.6% of urines were positive for 1-PP in the buspirone participants overall with rates of 95.5% and 92.8% in the female and male subgroups, respectively (data not shown). All study participants reached the target dose (60 mg/day) and approximately 89% of participants were maintained at the target dose.

Table 2.

Summary of Medication Adherence and Tolerability

| All (n=62) | Female (n=23) | Male (n=39) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Buspirone (n=35) | Placebo (n=27) | Total (n=62) | Buspirone (n=11) | Placebo (n=12) | Total (n=23) | Buspirone (n=24) | Placebo (n=15) | Total (n=39) | |

| Medication Adherence | |||||||||

| % Buspirone/Placebo pills taken: | |||||||||

| Self-report: mean (SD) a | 88.7% (21.6%) | 91.2% (17.0%) | 89.8% (19.7%) | 78.2% (32.5%) | 96.2% (4.5%) | 87.6% (24.0%) | 93.5% (12.5%) | 87.2% (22.0%) | 91.1% (16.8%) |

| Pill count: mean (SD)b | 94.4% (9.6%) | 95.8% (5.2%) | 95.0% (8.0%) | 92.2% (12.6%) | 97.1% (3.0%) | 94.7% (9.1%) | 95.5% (8.0%) | 94.8% (6.4%) | 95.2% (7.3%) |

| % Bottle openings: mean (SD) | 84.5% (22.0%) | 84.4% (20.5%) | 84.5% (21.2%) | 76.2% (31.1%) | 92.0% (7.9%) | 84.5% (23.1%) | 88.3% (15.6%) | 78.4% (25.4%) | 84.5% (20.2%) |

| % Urine samples positive for 1-PP: mean (SD) | 81.5% (25.4%) | -- | -- | 82.4% (27.3%) | -- | -- | 81.0% (25.1%) | -- | -- |

| Medication Tolerability | |||||||||

| Tolerability of maximum Buspirone/Placebo dose: | |||||||||

| Reached maximum: n (%) | 35 (100.0%) | 27 (100.0%) | 62 (100.0%) | 11 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | 23 (100.0%) | 24 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 39 (100.0%) |

| Sustained dose at maximum: n (%) | 31 (88.6%) | 24 (88.9%) | 55 (88.7%) | 10 (90.9%) | 11 (91.7%) | 21 (91.3%) | 21 (87.5%) | 13 (86.7%) | 34 (87.2%) |

Self-reported adherence was calculated as (total mgs. taken)/(total mgs. prescribed) expressed as a percent;

Pill count adherence was calculated: (pills dispensed − pills returned − pills reported lost)/(pills dispensed − expected pills returned) expressed as a percent. In cases where participants failed to return their medication bottles, those bottles were excluded from the analysis.

Efficacy Outcomes

All participants (n=62)

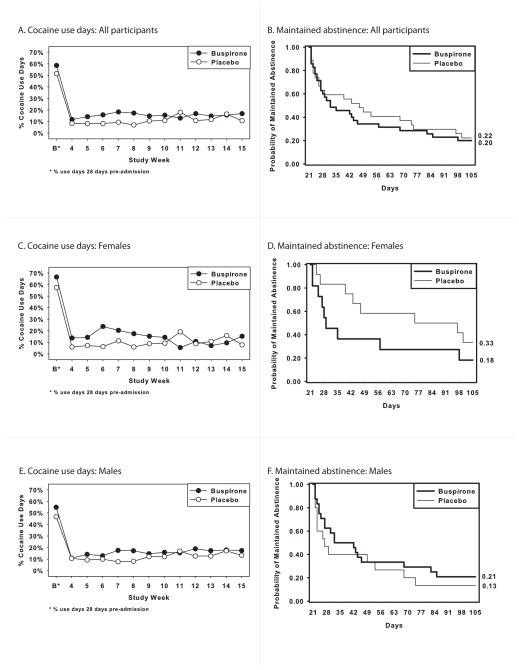

The average maximum number of days of continuous cocaine abstinence was 39.7 (SD=31.4) for the buspirone and 42.1 (SD=31.1) for the placebo participants, which was not a statistically significant difference (X2(1)=0.05, p=.82). In contrast, there was a significant treatment-by-time interaction for proportion of cocaine-use days (X2(1)=6.06, p=.01). A review of the associated graph (Figure 2A) indicates that this effect reflects a relative increase in use by the buspirone group early in the outpatient treatment phase (i.e., weeks 5–8). Kaplan-Meier curves for the probability of maintaining abstinence from cocaine as a function of treatment are provided in Figure 2B; there was no statistically significant treatment effect on days to first cocaine use (X2(1)=0.15, p=0.70).

Figure 2.

Proportion of cocaine use days and Kaplan-Meier curves for maintaining cocaine abstinence as a function of treatment arm for all participants (A, B), females (C, D), and males (E, F).

Females (n=23)

The average maximum number of days of continuous cocaine abstinence was 37.7 (SD=32.5) for the buspirone and 52.0 (SD=32.9) for the placebo participants, which was not a statistically significant difference (X2(1)=1.80, p=.18). In contrast, there was a significant treatment-by-time interaction for proportion of cocaine-use days (X2(1)=15.26, p<.0001). A review of the associated graph (Figure 2C) indicates that this effect reflects a relative increase in cocaine use by the buspirone group early in the outpatient treatment phase (i.e., weeks 4–10). There was a trend for a significant treatment effect on days to first cocaine use (X2(1)=3.20, p=.067), reflecting the tendency for quicker relapse to cocaine use in the buspirone, relative to placebo, participants (Figure 2D).

Males (n=39)

The average maximum number of days of continuous cocaine abstinence was 40.5 (SD=31.6) for the buspirone and 34.3 (SD=28.1) for the placebo participants, which was not a statistically significant difference (X2(1)=3.06, p=.08). There was no significant treatment effect (X2(1)=0.01, p=.91) or treatment-by-time interaction (X2(1)=0.14, p=.70) for proportion of cocaine-use days (Figure 2E). Finally, there was no statistically significant treatment effect on days to first cocaine use (X2(1)=1.40, p=.24; Figure 2F).

Safety outcomes

The occurrence of treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) related to study medication was significantly higher in the buspirone, relative to placebo, group (Table 3). Within gender subgroups, the occurrence of TEAEs related to study medication was significantly higher in the buspirone, relative to placebo, group in the females but not in the males (Table 3). One AE, dizziness, occurred at a rate of 5% or more in the buspirone group, and at a statistically significantly higher rate than in the placebo group in the sample overall (p=.0005) and in the females (p=.005); there was a trend for greater dizziness in the buspirone than the placebo group in the males (p=.057). There was no evidence of an increased risk for suicidal ideation in the buspirone group. Three participants, all of whom were in the buspirone arm, experienced a treatment emergent serious adverse event (SAE). The three events, which were rated as unrelated to the study medication, entailed inpatient hospital admissions for lower respiratory infection (n=1), chest pain (n=1), and pneumonia (n=1).

Table 3.

Summary of Treatment Emergent Adverse Events

| All (n=62) | Female (n=23) | Male (n=39) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| TEAE, n (%) | Buspirone (n=35) | Placebo (n=27) | P Valuea | Buspirone (n=11) | Placebo (n=12) | P Valuea | Buspirone (n=24) | Placebo (n=15) | P Valuea |

| Any TEAEsb | 33 (94.3) | 21 (77.8) | 0.0689 | 11 (100.0) | 11 (91.7) | 1.0000 | 22 (91.7) | 10 (66.7) | 0.0846 |

| TEAEs related to study medicationc | 22 (62.9) | 8 (29.6) | 0.0094 | 9 (81.8) | 4 (33.3) | 0.0361 | 13 (54.2) | 4(26.7) | 0.0920 |

| Any serious TEAE | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2504 | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4783 | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.5142 |

| Discontinued medication due to TEAEs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| Most frequent TEAEs d by MedDRA®e preferred term | |||||||||

| Nervous system disorders | |||||||||

| Dizziness | 15 (42.9) | 1 (3.7) | 0.0005 | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0046 | 9 (37.5) | 1 (6.7) | 0.0574 |

| Somnolence | 3 (8.6) | 2 (7.4) | 1.0000 | 2 (18.2) | 1 (8.3) | 0.5901 | 1 (4.2) | 1 (6.7) | 1.0000 |

| Infections and infestations | |||||||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 8 (22.9) | 4 (14.8) | 0.4268 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (8.3) | 1.0000 | 7 (29.2) | 3 (20.0) | 0.7110 |

| Bronchitis | 2 (5.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1.0000 | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4783 | 1 (4.2) | 1 (6.7) | 1.0000 |

| Influenza | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2504 | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2174 | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||||||||

| Nausea | 8 (22.9) | 2 (7.4) | 0.1642 | 3 (27.3) | 2 (16.7) | 0.6404 | 5 (20.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1359 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (5.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1.0000 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1.0000 | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.5142 |

| Dyspepsia | 2 (5.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1.0000 | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2174 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0.3846 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | |||||||||

| Back pain | 5 (14.3) | 2 (7.4) | 0.4550 | 2 (18.2) | 2 (16.7) | 1.0000 | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2713 |

| Arthralgia | 2 (5.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1.0000 | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4783 | 1 (4.2) | 1 (6.7) | 1.0000 |

| Pain in Extremity | 2 (5.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1.0000 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (8.3) | 1.0000 | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | |||||||||

| Pulmonary congestion | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.5003 | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4783 | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0000 |

| Sinus congestion | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.5003 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.5142 |

| Weight increased | 2 (5.7) | 1 (3.7) | 1.0000 | 2 (18.2) | 1 (8.3) | 0.5901 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| Insomnia | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.5003 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.5142 |

Note. TEAE = Treatment Emergent Adverse Event;

P values are from either Fisher’s exact test or Pearson chi-square, depending on marginal frequency counts.

TEAEs are adverse events defined as a new illness, or an exacerbation of a pre-existing condition, occurring between the first dose of study drug and one week after the last dose of study drug;

TEAE rated as possibly, probably or definitely related to treatment;

TEAEs presented here were reported by >5% of buspirone group and at a greater rate than by the placebo group, in the full sample (n=62);

MedDRA® the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities terminology is the international medical terminology developed under the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). MedDRA® is a registered trademark of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA).

DISCUSSION

The present pilot trial was the first to evaluate buspirone as a relapse-prevention treatment for cocaine dependence. The pilot was successful in demonstrating the feasibility of conducting a large-scale trial based on enrollment, dose escalation tolerability, and adherence. The study however, even with small numbers and, counter to prediction, suggests that buspirone had no beneficial effect on relapse to cocaine use and had a significant negative effect on proportion of cocaine-use days in female participants. This suggests that the use of buspirone for cocaine-dependent women may worsen their cocaine-use outcomes, although, given the small sample of women in the trial (n=23), this finding would need to be replicated before being given significant consideration clinically. The results for the male participants revealed no significant buspirone treatment effect which suggests that buspirone is not an effective cocaine-dependence treatment for males but, again, based on the small sample of men in the trial (n=39), this finding would also need to be replicated prior to concluding that buspirone is not effective.

The results from the present pilot trial are inconsistent with pre-clinical studies finding that buspirone significantly decreases cocaine-cue reinstatement in rats12 and that both acute11, 13 and chronic14 buspirone decrease cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Of import, these pre-clinical studies have been completed only with males and, thus, the discrepancy between the pre-clinical and present study results may reflect, in part, gender differences in dopaminergic function and dopaminergic-agent response.17–23 The present results are consistent with a small (n=35) 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the association between impulsivity, severity of cocaine use, and buspirone treatment, which found no significant treatment effect of buspirone on cocaine-use outcomes.29

The present study had several strengths. First, this trial was conducted at 6 sites, which enhances the generalizability of the results. Another study strength is that it was conducted with individuals seeking treatment at SUD treatment programs and, thus, the results are likely generalizable to individuals in treatment for stimulant-dependence disorders.30 Other strengths include the very high retention and good medication adherence rates. The small sample size of the present trial is a significant limitation in that small trials do not provide accurate estimates of treatment effect,31 nor was this study adequately powered to detect differences in efficacy outcomes since the primary goal of this study was to address important operational aspects that would be applied to a second, larger trial. However, the results from this pilot trial do not provide a strong rationale for conducting a larger follow-up trial. Evaluation of a single dose of buspirone is another potential limitation of the present trial. There is evidence that buspirone’s affinity for D3 and D4 receptors is comparable to its affinity for 5HT1A receptors and, thus, standard clinically-effective doses would likely effect D3 and D4.32 The dose evaluated in this trial, 60 mg, is the highest FDA-approved dose for treating generalized anxiety disorder and, thus, would be expected to occupy D3 and D4 receptors. Still, an evaluation of other doses of buspirone might have produced different results from those observed in this trial. In conclusion, the results from the present trial suggest that buspirone is not an effective relapse-prevention treatment for cocaine dependence and may have a significant negative effect on cocaine-use outcomes in cocaine-dependent women.

Clinical Points.

There is currently no FDA-approved medication for the treatment of cocaine-dependence.

Buspirone, which is an FDA-approved treatment for generalized anxiety disorder, may have a significant negative effect on cocaine-use outcomes in cocaine-dependent women.

Buspirone does not appear to be an effective relapse prevention treatment for cocaine dependence.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the following grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse: U10-DA013732 to University of Cincinnati (Dr. Winhusen); U10-DA020036 to University of Pittsburgh (Dr. Daley), U10-DA013720 to University of Miami School of Medicine (Drs. Szapocznik and Metsch); U10-DA013727 to Medical University of South Carolina (Dr. Brady); U10-DA020024 to University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dr. Trivedi); U10DA013043 (Dr. Woody).

The participating sites were: Addiction Medicine Services, Pittsburgh, PA; Gateway Community Services, Jacksonville, FL; Morris Village - Lexington/Richland Alcohol & Drug Abuse Council, Columbia, SC; Maryhaven, Inc., Columbus, OH; Nexus Recovery, Inc., Dallas, TX; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors report no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, Center for Behaviorial Health Statistics and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2010. United Nations Publication; Sales No. E.10.XI.13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuehn BM. Scientists target cocaine addiction. JAMA. 2009;302(24):2641–2642. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vorel SR, Ashby CR, Jr, Paul M, et al. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22(21):9595–9603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xi ZX, Newman AH, Gilbert JG, et al. The novel dopamine D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904 inhibits cocaine’s rewarding effects and cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(7):1393–1405. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidbreder CA, Newman AH. Current perspectives on selective dopamine D(3) receptor antagonists as pharmacotherapeutics for addictions and related disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:4–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boileau I, Payer D, Houle S, et al. Higher binding of the dopamine D3 receptor-preferring ligand [11C]-(+)-propyl-hexahydro-naphtho-oxazin in methamphetamine polydrug users: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurosci. 2012;32(4):1353–1359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4371-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lader M. Can buspirone induce rebound, dependence or abuse? Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1991;12:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julien RM. A Primer of Drug Action: A Concise, Nontechnical Guide to the Actions, Uses, and Side Effects of Psychoactive Drugs. 10. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kula NS, Baldessarini RJ, Kebabian JW, Neumeyer JL. S-(+)-aporphines are not selective for human D3 dopamine receptors. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1994;14(2):185–191. doi: 10.1007/BF02090784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergman J, Roof RA, Furman CA, et al. Modification of cocaine self-administration by buspirone (BuSpar(R)): potential involvement of D3 and D4 dopamine receptors. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shelton KL, Hendrick ES, Beardsley PM. Efficacy of buspirone for attenuating cocaine and methamphetamine reinstatement in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;129(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold LH, Balster RL. Effects of buspirone and gepirone on i.v. cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;108(3):289–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02245114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mello NK, Fivel PA, Kohut SJ, Bergman J. Effects of Chronic Buspirone Treatment on Cocaine Self-Administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(3):455–467. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ersche KD, Bullmore ET, Craig KJ, et al. Influence of compulsivity of drug abuse on dopaminergic modulation of attentional bias in stimulant dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):632–644. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winhusen T, Brady KT, Stitzer M, et al. Evaluation of buspirone for relapse-prevention in adults with cocaine dependence: an efficacy trial conducted in the real world. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(5):993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poth LS, O’Connell BP, McDermott JL, Dluzen DE. Nomifensine alters sex differences in striatal dopaminergic function. Synapse. 2012;66(8):686–693. doi: 10.1002/syn.21554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riccardi P, Park S, Anderson S, et al. Sex differences in the relationship of regional dopamine release to affect and cognitive function in striatal and extrastriatal regions using positron emission tomography and F-18 fallypride. Synapse. 2011;65(2):99–102. doi: 10.1002/syn.20822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callahan PM, Cunningham KA. Modulation of the discriminative stimulus properties of cocaine: comparison of the effects of fluoxetine with 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36(3):373–381. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin-Soelch C, Szczepanik J, Nugent A, et al. Lateralization and gender differences in the dopaminergic response to unpredictable reward in the human ventral striatum. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33(9):1706–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munro CA, McCaul ME, Wong DF, et al. Sex differences in striatal dopamine release in healthy adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(10):966–974. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton LR, Czoty PW, Gage HD, Nader MA. Characterization of the dopamine receptor system in adult rhesus monkeys exposed to cocaine throughout gestation. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210(4):481–488. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1847-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji J, Dluzen DE. Sex differences in striatal dopaminergic function within heterozygous mutant dopamine transporter knock-out mice. J Neural Transm. 2008;115(6):809–817. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nader MA, Nader SH, Czoty PW, et al. Social dominance in female monkeys: dopamine receptor function and cocaine reinforcement. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha R, Garcia M, Paliwal P, Kreek MJ, Rounsaville BJ. Stress-induced cocaine craving and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses are predictive of cocaine relapse outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):324–331. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paliwal P, Hyman SM, Sinha R. Craving predicts time to cocaine relapse: further validation of the Now and Brief versions of the cocaine craving questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(3):252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyman SM, Paliwal P, Chaplin TM, Mazure CM, Rounsaville BJ, Sinha R. Severity of childhood trauma is predictive of cocaine relapse outcomes in women but not men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92(1–3):208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(1):134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Barratt ES, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, Grabowski J. The impact of impulsivity on cocaine use and retention in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21(4):193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winhusen T, Winstanley EL, Somoza E, Brigham G. The potential impact of recruitment method on sample characteristics and treatment outcomes in a psychosocial trial for women with co-occurring substance use disorder and PTSD. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1–3):225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):484–489. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newman AH, Blaylock BL, Nader MA, Bergman J, Sibley DR, Skolnick P. Medication discovery for addiction: translating the dopamine D3 receptor hypothesis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012 Oct 1;84(7):882–890. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]