Abstract

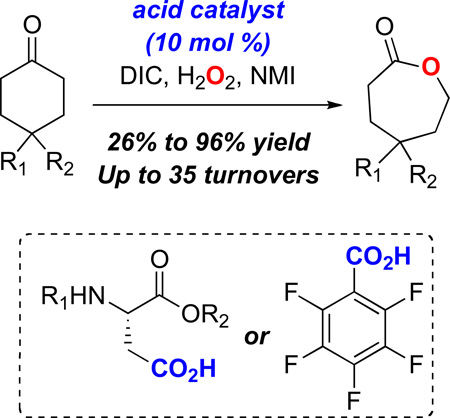

The combined action of carbodiimide and hydrogen peroxide upon exposure to carboxylic acid catalysts serves to generate transient peracids that can be engaged in the Baeyer-Villiger rearrangement of ketones to lactones. Up to 35 turnovers of the catalytic cycle may be achieved. The conditions are especially useful in the context of reactive cyclohexanones, and allow the use of H2O2 as the terminal oxidant. A singular example of a chiral catalyst demonstrates, in principle, that enantioselective catalysis will be possible with this strategy for catalyst turnover.

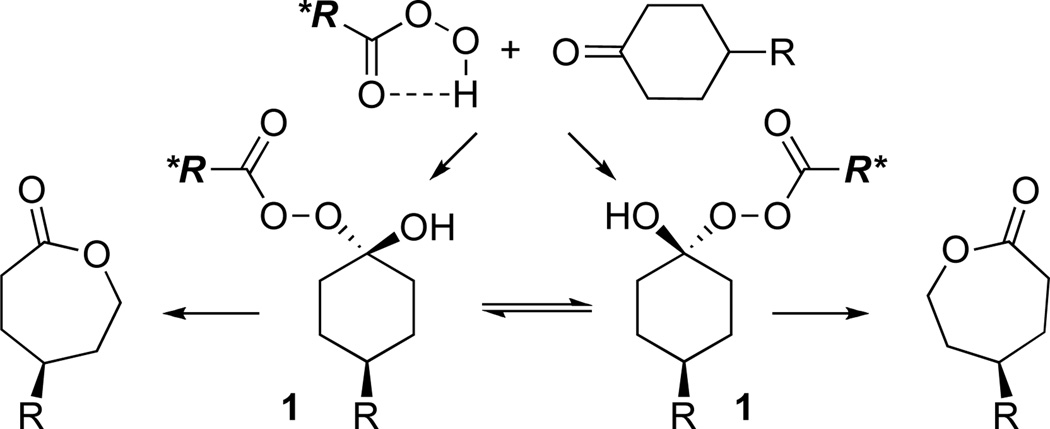

In spite of the fact that the oxidative conversion of ketones/aldehydes to esters via the Baeyer-Villiger reaction (BV) has been known for more than one hundred years,1 there remain innumerable optimizations of this venerable reaction yet to be developed. One major challenge in the field has been the development of robust catalytic cycles that allow for efficient and rapid catalyst turnover. Moreover, highly enantioselective variants of the BV reaction are almost exclusively performed by enzymatic systems,2 which by their nature, exhibit substrate specificity. Nonenzymatic catalysts for this goal have been demonstrated with organometallic reagents3 as well as with potential mimics of biological “Baeyer-Villiger-ases,”4 including systems based on flavin5a and organophosphoric acid moieties.4b In each case, wide generality has not yet been achieved, and efficiency of some catalysts has been limited in terms of overall turnover number. A new entry into efficient BV catalysis, with the potential for a larger substrate scope could derive from trivially accessible and tunable catalysts. The design principles for a new catalytic cycle could then focus on rapid rearrangement of the Criegee intermediate (1, Scheme 1), and ultimately control of the rotational behavior of the Criegee intermediate.

Scheme 1.

Peracid BV Oxidation of Cyclic Ketones

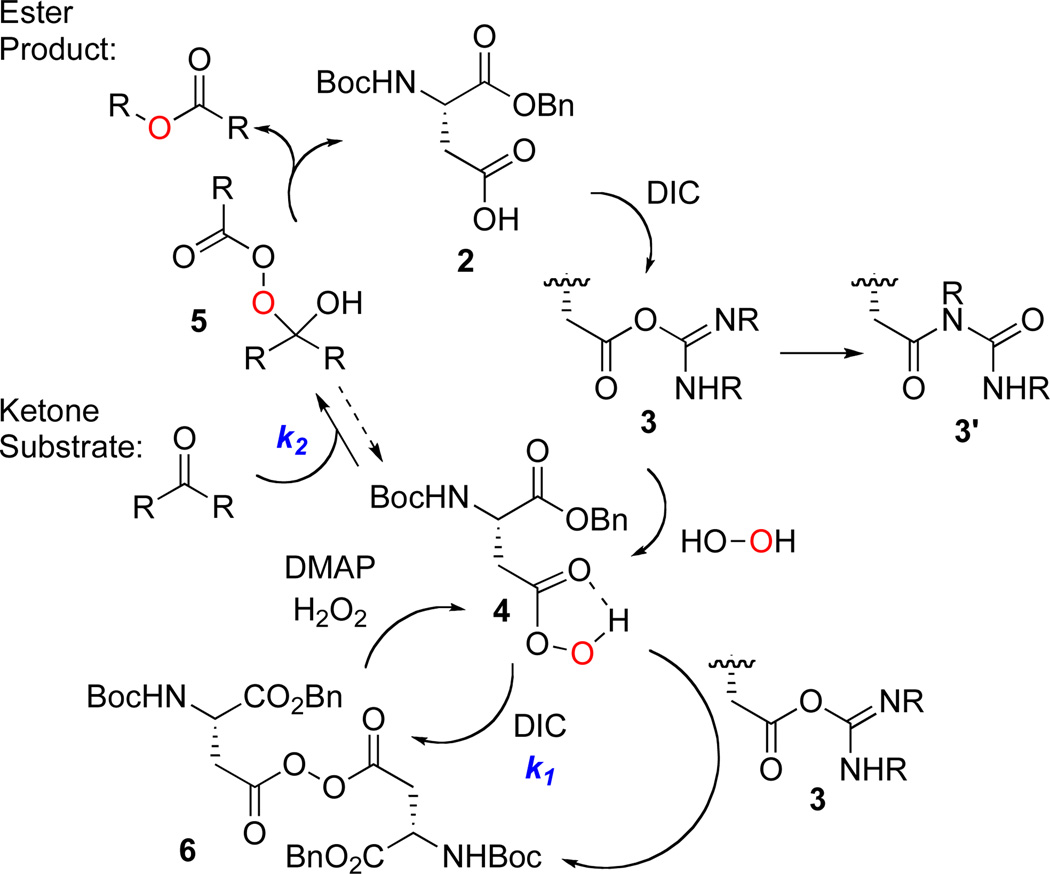

One strategy for this goal involves the development of catalytic carboxylic acids that may shuttle between the per- acid oxidation state, and a carboxylic acid resting state. Indeed, we have recently found that aspartic acid may function in this capacity for enantioselective epoxidation catalysis.6 We now wish to establish that the same catalysis concept is portable to the oxidation of ketones (e.g., 2, Scheme 2). This strategy may represent a fundamentally new catalytic cycle for the BV reaction. We targeted carboxyl activation through the combined action of diisopropyl carbodiimide (DIC), and 4-dimethylamino pyridine (DMAP). Capture of intermediate 3 with H2O2 as the terminal oxidant leads to the formation of aspartate peracid (4, Scheme 2). The classical BV reaction then leads to product esters, and regeneration of 2 for re-entry into the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 2.

A Catalytic Cycle for the BV Oxidation

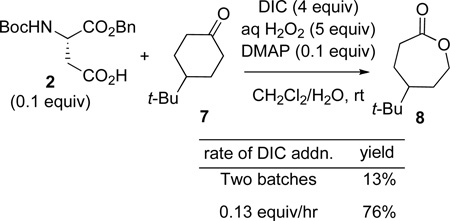

Initially, exposure of 4-t-butyl-cyclohexanone (eq 1, 7) to 10 mol% of 2 activated by DIC/H2O2/DMAP resulted in a low yield of lactone 8 (13%; eq 1). We attributed the low yield to reaction of the aspartic peracid with excess DIC to give inactive diacyl peroxide 6 (k1; Scheme 2).7 This process was already observed in our epoxidation study, and the introduction of a nucleophilic co-catalyst (DMAP or N-methylimidazole; NMI) enabled perhydrolysis of the diacyl peroxide and regeneration of the active peracid (i.e., 6 to 4 in Scheme 2). In the context of the BV, a nucleophilic additive likewise facilitates diacyl peroxide perhydrolysis.8 Furthermore, the low yield of lactone suggested that the rate of the reaction of peracid with ketone (k2, Scheme 2) was slow in comparison to the rate of peracid reaction with DIC (k1, Scheme 2). Thus, to compensate, we sought to maintain a low concentration of DIC during the reaction through slow addition of DIC. Indeed, addition of DIC at a rate of 0.13 equiv/hr, in the presence of 0.1 equiv of 2, delivers 8 in 76% yield (eq 1).

|

(1) |

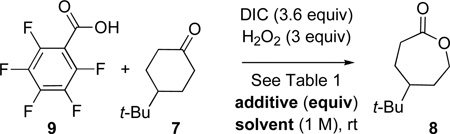

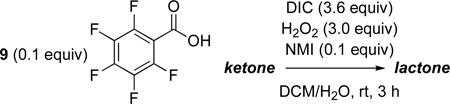

Having adapted 2 for catalytic BV oxidation, we wondered next if use of more acidic carboxylic acids would lead to more reactive peracid moieties, obviating the need for slow addition of DIC, and perhaps increasing the number of catalyst turnovers. Indeed, under conditions where 2 (pKa ~ 4.4)9 produces a poor 15% yield of lactone 8, PhF5CO2H (9; pKa = 1.74)10 catalyzes the formation of 8 in a much-improved yield of 86% (eq 2; Table 1, entry 1). Indeed, with this catalyst, even when DIC is added in one batch at the beginning of the experiment, the yield of 6 is reduced only moderately (68% yield, Table 1, entry 2).

Table 1.

Use of PhF5CO2H (9) as a catalyst for the BV.

| entry | equiv 9 | additive (equiv) | solvent | yielda |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.1 | DMAP (0.1) | DCM | 86% |

| 2b | 0.1 | DMAP (0.1) | DCM | 68% |

| 3 | 0.1 | - | DCM | 20% |

| 4 | 0.1 | NMI (0.1) | DCM | 91% |

| 5 | 0.1 | NMO (0.1) | DCM | 50% |

| 6 | 0.1 | DMAP (0.1) | Et2O | 58% |

| 7 | 0.1 | DMAP (0.1) | THF | 42% |

| 8 | 0.1 | DMAP (0.1) | PhMe | 48% |

| 9c | 0.1 | DMAP (0.1) | DCM | 42% |

| 10 | - | DMAP (0.1) | DCM | 0% |

| 11d | 0.1 | - | DCM | 0% |

| 12 | 0.05 | NMI (0.1) | DCM | 69% |

| 13 | 0.01 | DMAP (0.1) | DCM | 18% |

| 14 | 0.01 | DMAP (0.1) + HOBt (0.1) | DCM | 35% |

Calculated by comparison to an internal NMR standard after DIC addition was complete. DIC was always added at 1.2 DIC equiv/h.

DIC was added in one batch.

UHP (3 equiv) was used as the peroxide source.

Experiment run without DIC or additive.

|

(2) |

With a more reactive peracid catalyst, we next set out to define general experimental conditions for the BV reaction. As expected, when no nucleophilic additives were used, yield dropped substantially (20% yield, Table 1, entry 3). Also, whereas DMAP and NMI are similarly effective as additives (86% and 91% yield respectively, Table 1, entries 1 and 4), other nucleophilic species were far less so. Of the nucleophiles screened (HOBt, pyridine oxide, Ph3P=O, NMO) only NMO had a discernable effect on lactone formation (50% yield, Table 1, entry 5).

Solvent effects are also apparent. DCM (CH2Cl2) facilitates the largest amount of lactone formation (86% yield, Table 1, entry 1). This is in contrast to ethers (Table 1; Et2O, 58% yield, entry 6; THF, 42% yield, entry 7) or aromatic solvents (PhMe, 48% yield, Table 1, entry 8). Anhydrous conditions may be employed by substituting the urea-H2O2 complex (UHP) for 30% H2O2(aq), albeit at the cost of yield (42%, Table 1, entry 9).

The intermediacy of peracids in the above oxidations is supported by further control experiments. For instance, no lactone was produced in the absence of acid catalyst (Table 1, entry 10). Also, because no ketone oxidation takes place when DIC is omitted (Table 1, entry 11), general acid catalysis by RCO2H appears inoperative under these conditions.

We have also briefly examined the limits of catalyst turnover. Lowering the catalyst loading to 5 mol% increased the number of turnovers (69% yield, 14 turnovers, Table 1, entry 12). On the other hand, a 1 mol% loading of PhF5CO2H (9) only increased the turnover number to 18 (Table 1, entry 13), pointing to the existence of a catalyst deactivation pathway. We hypothesized that deactivation involves rearrangement of O-acyl ureas to N-acyl ureas (cf. 3 to 3’, Scheme 2). Accordingly, the addition of HOBt (10 mol%) to a reaction containing 1 mol% 9 led to the observation of 35 cycles (Table 1, entry 14).

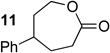

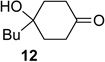

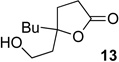

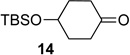

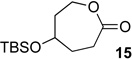

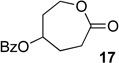

We next examined the substrate scope of catalyst 9 under these reaction conditions. 4-Substituted cyclohexanones are excellent substrates for rearrangement with catalyst 9. Ketone 10 (Table 2, entry 1) was as reactive as 7 and produced the desired lactone in 96% isolated yield. Tertiary alcohol-containing ketone 12 rearranged to the 5-membered lactone 13 (Table 2, entry 2), presumably via the kinetically produced 7-membered lactone. TBS-ethers are tolerated, and lactone 15 is obtained in 78% yield (Table 2, entry 3). Finally, the more electron deficient ketone 16 is less reactive and produced the corresponding lactone 17 in only 48% yield (Table 2, entry 4). Substituted cyclohexanones participate and abide by anticipated migratory aptitudes.1b For instance, 2-phenyl cyclohexanone (18), delivers lactone 19 in 78% yield (Table 2, entry 5). Less reactive substrates rearrange in lower yields. For instance, bicycle 20 produces ester 21 in only 23% yield within 8 h (Table 2 entry 6). Tetralone 22 also reacts slowly, giving 23 in 10% yield (Table 2, entry 7). Nevertheless, catalyst 9 processes moderately reactive ketones efficiently.

Table 2.

Substrate scope of PhF5CO2H (9) in BV reaction.

Yield was measured by comparison to an internal NMR standard, or by isolation of the product by chromatography. Except where noted, DIC was always added at 1.2 DIC equiv/h.

Reaction run with 4 equiv DIC (Rate of additions 0.5 DIC equiv/h), 5 equiv aq H2O2 and DMAP (0.1 equiv) for 8 h.

DIC was added at 0.6 DIC equiv/h for 6 h.

|

(3) |

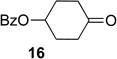

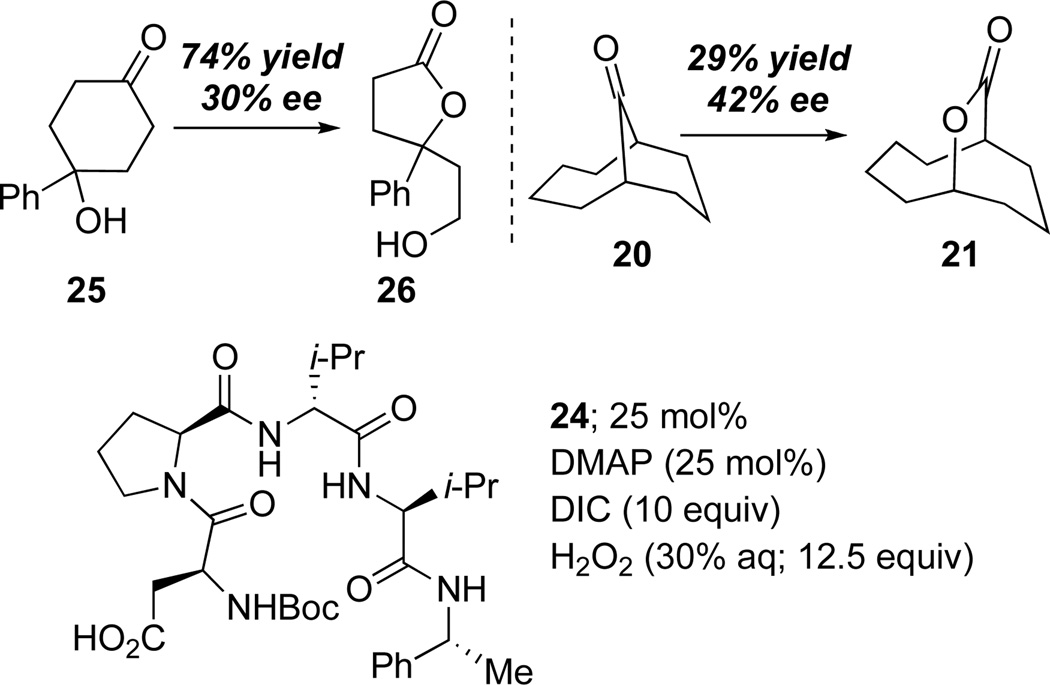

The development of nonenzymatic catalytic enantioselective BV oxidations is, perhaps, a field in its infancy. Nonetheless, we wish to report preliminary data that shows the translation of these reaction conditions to the desymmetrization of prochiral ketones. Aspartate-containing peptide 24 mediates the oxidation of ketones 25 and 20 to give the corresponding lactones with modest, but appreciable selectivity (65:35 e.r. and 71:29 e.r., respectively; Scheme 3). As expected, the catalysis with these low reactivity substrates proceeds with modest turnover efficiency. Nonetheless, these early experiments document a remarkable potential for peptide-based peracids to control the subtle bond rotations associated with enantioselective BV processes (Scheme 1), an area we will now explore in depth.

Scheme 3.

Preliminary study of enantioselective BV.

In conclusion, we have found a nonenyzymatic process for amino acid and peptide-catalyzed Baeyer-Villiger oxidations. Our approach is inspired by the capability of peracids to effect BV reactions, and the portability of acid/peracid catalytic cycles from epoxidation chemistry to BV reactions. The versatility of the catalytic cycle may allow a common set of catalysts to be studied in parallel development of epoxidations, BV reactions, and other processes. The portability of catalysts and catalytic cycles from one reaction type to another is a potential hallmark of “privileged” catalysts.11 At the same time, the adaptability of catalyst scaffolds across a broad spectrum of chemical reactions is also a hallmark of enzyme evolution.12 This work may contribute to a groundwork that allows for further exploration of analogies between synthetic and enzymatic catalysts.13

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the NIH (NIGMS) and Boehringer-Ingelheim, each for partial support of this research. We are also grateful to Charles E. Jakobsche for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION. Experimental procedures and characterization. This material is available at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Baeyer A, Villiger V. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1899;32:3625. [Google Scholar]; (b) Krow GR. Org. React. 1993;43:251. [Google Scholar]; (c) ten Brink G–J, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:4105. doi: 10.1021/cr030011l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Mihovilovic MD. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006;10:1265. [Google Scholar]; (b) Katsuki T. Russ. Chem. Bull. Int. Ed. 2004;53:1859. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Colladon M, Scarso A, Strukul G. Synlett. 2006:3515. [Google Scholar]; (b) Frison JC, Palazzi C, Bolm C. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:6700. [Google Scholar]; (c) Watanabe A, Uchida T, Irie R, Katsuki T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:5737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306992101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mihovilovic MD, Muller B, Stanetty P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002;22:3711. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Murahashi S–I, Ono S, Imada Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2366. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020703)41:13<2366::AID-ANIE2366>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu S, Wang Z, Zhang X, Zhang X, Ding K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peris G, Jakobsche CE, Miller SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8710. doi: 10.1021/ja073055a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene FD, Kazan J. J. Org. Chem. 1963;28:2168. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Exposure of 7 to benzoyl peroxide and aq. H2O2 in DCM failed to give lactone 8 after 16 h. Performing the reaction with DMAP (0.1 equiv) delivers 8 in 89% yield.

- 9.Stryer L. Biochemistry. W.H. Freeman; New York: 1988. p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stetzenbach KJ, Jensen SL, Thompson GM. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982;16:250. doi: 10.1021/es00099a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon TP, Jacobsen EN. Science. 2003;299:1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1083622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Koonin EV. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003;7:12. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller SJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:601. doi: 10.1021/ar030061c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.