Abstract

Background:

Trauma injury is the leading cause of mortality and hospitalization worldwide and the leading cause of potential years of productive life lost. Patients with multiple injuries are prevalent, increasing the complexity of trauma care and treatment. Better understanding of the nature of trauma risk and outcome could lead to more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective review of 1178 trauma patients with Injury Severity Score (ISS) ≥ 9, who were admitted to the Acute and Emergency Care of an acute care hospital between January 2011 and December 2012. The statistical analysis included calculation of percentages and proportions and application of test of significance using Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test where appropriate.

Results:

Over the study period, 1178 patients were evaluated, 815 (69.2%) males and 363 (30.8%) females. The mean age of patients was 52.08 ± 21.83 (range 5-100) years. Falls (604; 51.3%) and road traffic accidents (465; 39.5%) were the two most common mechanisms of injury. Based on the three most common mechanisms of injury, i.e. fall on the same level, fall from height, and road traffic accident, the head region (484; 45.40%) was the most commonly injured in the body, followed by lower limbs (377; 35.37%) and thorax (299; 28.05%).

Conclusion:

Fall was the leading cause of injury among the elderly population with road traffic injuries being the leading cause among the younger group. There is a need to address the issues of injury control and prevention in these areas.

Keywords: Falls, injury mechanisms, road traffic accidents, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Trauma injury accounts for 9% of global mortality and are a threat to health worldwide. For every death, it is estimated that there are multiple hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and doctors’ appointments.[1] Injuries sustained are predominantly due to high energy blunt trauma such as a fall from height, road or workplace trauma.[2] Patients with multiple injuries are prevalent, increasing the complexity of trauma care and treatment. Better understanding of the nature of trauma risk and outcome could lead to more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

This study aimed to:

Broadly evaluate the epidemiologic characteristics of trauma in a newly established acute care hospital in Singapore.

Examine the relationship between the sites of injury and the mechanisms of injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a retrospective analysis of all trauma patients with Injury Severity Score (ISS) ≥9, who were admitted into the Acute and Emergency Care (A&E) of our hospital in Singapore from January 2011 to December 2012. Ethics approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group (NHG) Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) prior to initiation of the study.

All traumatic injuries that resulted from any physical injury, suicide attempt by hanging, drowning, and falling object/s were included. Poisonings, isolated fracture neck of femur arising from same level fall for patients aged ≥65 years old, bites from animals, trauma patients who were discharged or transferred to other institutions, non-trauma-related deaths, and complications or adverse events arising from medical or surgical treatment were excluded from the study.

Data of the cases were obtained from the patients’ medical records and the hospital registration system. Medico-legal autopsy reports were retrieved for trauma patients who died in the A&E and when details of injuries from the clinicians’ records as well as investigation results could not be fully determined. All patients were captured in the Singapore National Trauma Registry (NTR) managed by the hospital trauma service of the Department of Surgery.

The Singapore National Trauma Registry (NTR) contains anatomical injury codes, indicators of physiological response to injury, and patient demographics. Anatomic injuries are described with the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) © 2005 UPDATE 2008 version according to guidelines published by the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine (AAAM).[3] Physiological response to injury, which was evaluated upon arrival at the resuscitation room, is described by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and respiratory rate (RR). Epidemiologic factors such as patients’ age, sex, ethnic group, Injury Severity Score (ISS), Revised Trauma Score (RTS), Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS), A&E admission time, mechanism of injuries, and type of organ injury sustained were studied.

The Injury Severity Score (ISS) is the most widely used measure of injury severity. It is an anatomical scoring system that provides an overall score for patients with multiple injuries. Each injury is assigned an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score and is allocated to one of the six body regions (Head, Face, Chest, Abdomen, Extremities, including pelvis, and External). Only the highest AIS score in each body region is used. The three most severely injured body regions have their scores squared and added together to produce the ISS score. The ISS score ranges from one to 75 and its value correlates with the risk of mortality.[4] Patients who died at A&E or hospitalized with ISS ≥9 were recorded in the trauma registry as they were likely to be more severely injured, with higher probability to suffer socio-economic losses.

Revised Trauma Score (RTS) is a physiological scoring system with higher inter-rater reliability and demonstrable accuracy in predicting death. The RTS, which provides a general assessment of physiological derangement, consists of Glasgow Coma Scale, systolic blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Values for RTS range from 0 to 7.8408. A higher score indicates a better prognosis.[4]

Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) is the most commonly used combined scoring system in the world. TRISS combines the RTS, ISS, patient age, and mechanism of injury (blunt or penetrating) to estimate survival probability. The TRISS method offers a standard approach for evaluating outcome of trauma care. It is also a very useful tool for benchmarking predictions of risk-adjusted hospital mortality.[4,5]

The statistical analysis also included calculation of percentages and proportions as well as application of test of significance using Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate. The relationship between specific injury regions (e.g. head, neck, face, chest, abdomen, pelvis, spine/spinal column, upper limbs, and lower limbs) and mechanisms of injury (e.g. fall on the same level, fall from height and road traffic accident) were examined by estimating the odds ratio of association and their 95% confidence interval (CI). Due to the large number of specific associations that were examined, the aim of the analysis was to identify highly significant associations. For this reason, we reported exact P value of significance given the likelihood of spurious significance from multiple testings. Therefore, P values greater than 0.001 should be interpreted with caution. The 95% CI were omitted in the tables for clarity.

RESULTS

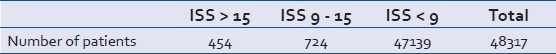

There were a total of 48,317 trauma emergency cases presented to the Acute and Emergency Care of our hospital [Table 1]. The analysis of 1178 patients with physical injuries, who were admitted into the Acute and Emergency Care (A&E) between the period 1st January 2011 and 31st December 2012, was carried out, and various statistical results were drawn from these cases.

Table 1.

Trauma emergency cases in Khoo Teck Puat Hospital

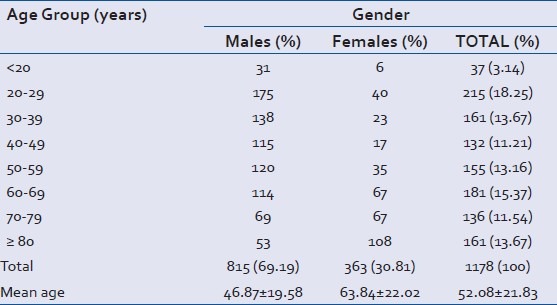

Age and sex incidence

The age-wise distribution of cases is shown in Table 2. More than half of all trauma cases (59.43%) were aged below 60. The most vulnerable age groups were between 20-29 years followed by 60-69 years of age, each comprising 18.25% (215 patients) and 15.37% (181 patients) of the total respectively. Mean age of all trauma cases was 52.08 ± 21.83 years (range 5-100) [Table 2]. The incidences of trauma in male (69.19%) far outnumbered female (30.81%), with a ratio of 2.25:1 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Age and sex distribution of cases (n = 1178)

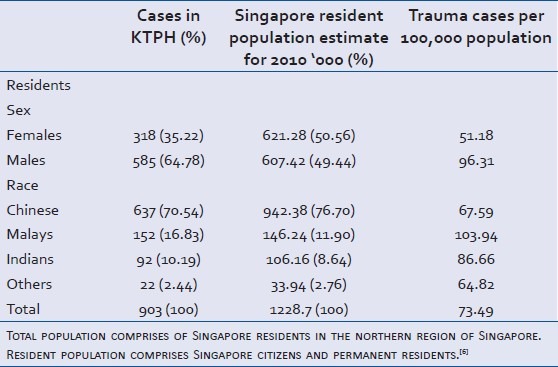

Trauma cases according to ethnicity

The demographic data are presented in Table 3. Based on the indigenous population of 1228, 700 in 2010, the annual incidence of trauma was 73.49 per 100,000 in the northern part of Singapore.[6]

Table 3.

Demographic data

When only the indigenous population was considered, Malays have higher trauma incidence rates (103.94 per 100,000), followed by two other races, Indians (86.66 per 100,000) and Chinese (67.59 per 100,000). The analysis of non-resident population was excluded due to unavailability of this population group data by geographical location.

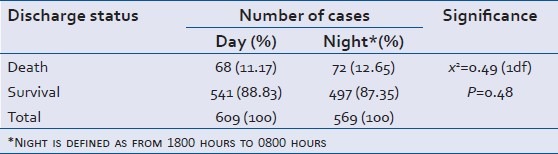

Time of admission into Acute and Emergency Care

The distribution of time of admission into the A&E is shown in Table 4. We arbitrarily chose 8 am and 6 pm as the cut-off timings since these are the normal working hours for staff in our hospital. Of the 1178 cases of trauma patients with ISS ≥9, 609 (51.7%) were admitted to the A&E during the day and 569 (48.3%) were admitted after 1800 hours. There were 68 (11.17%) deaths during the day compared to 72 (12.65%) deaths during the night. The association between these groups was considered to be not statistically significant (P = 0.48).

Table 4.

Time of admission into Acute and Emergency Care (n = 1178)

Trauma cases according to mechanism of injury

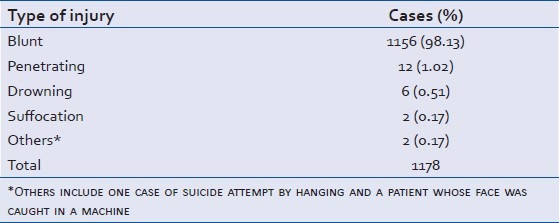

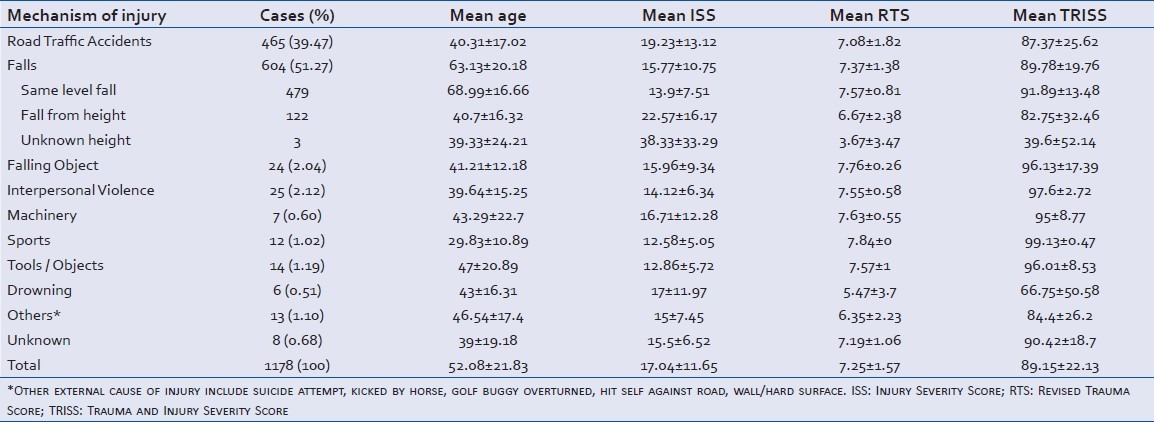

Blunt injury was the main cause of all injuries (98.13%) [Table 5]. Among the various injury types, falls was the commonest cause of injury (51.27%), followed by road traffic accidents (39.47%). Other injury mechanisms included falling objects (2.04%), interpersonal violence (2.12%), machinery (0.6%), drowning (0.51%), sports (1.02%), tools/objects (1.19%), and others (1.10%). The cause of injury sustained by eight patients (0.68%) could not be determined [Table 6]. These eight patients were found at the scene of injury by paramedics, and the patients were not able to recall the incidents.

Table 5.

Trauma cases according to type of injury (n = 1178)

Table 6.

Trauma cases according to mechanism of injury (n = 1178)

Falls

Of the 1178 cases, 604 (51.27%) resulted from falls. One hundred and twenty-two (10.36%) cases were due to major falls, i.e. fall from height, and 479 (40.66%) cases were due to minor falls, i.e. same level falls [Table 6]. Those who sustained injuries as a result of falls from height were generally younger with mean age of 40.7 ± 16.32 years as compared to 68.99 ± 16.66 years for those from same level falls. The mean ISS and mean TRISS for falls from height were 22.57 ± 16.17 and 82.75 ± 32.46. Those with same level falls had mean ISS of 13.9 ± 7.51 and mean TRISS of 91.89 ± 13.48.

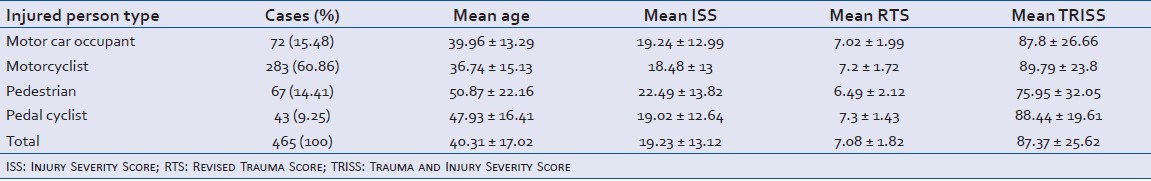

Road traffic accidents (RTA)

There were 465 (39.47%) RTA cases. More than half of all RTA cases (283; 60.86%) involved the use of motorcycles [Table 7]. Motorcar drivers and occupants were the second most vulnerable group contributing 72 (15.48%), followed closely by pedestrians 67 (14.41%). Motorcycle-related injuries were sustained by younger patients, with mean age of 36.74 ± 15.13 years, compared to pedestrians and pedal cyclists who were older. Cases involving pedestrians generated the highest mean ISS of 22.49 ± 13.82.

Table 7.

Trauma cases resulting from road traffic accident (n = 465)

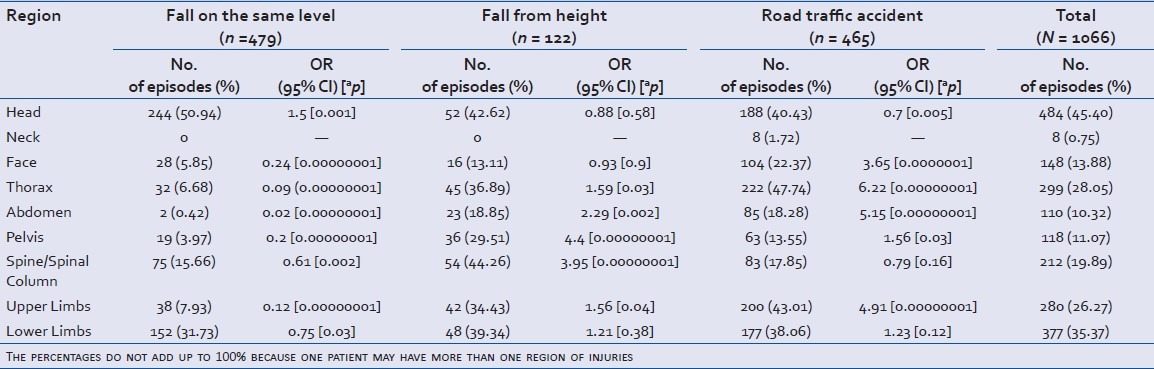

Pattern of injuries observed in parallel to mechanisms of injury

More than 50% (244) of injuries sustained by same level falls were head injuries. Head (52; 42.62%), thorax (45; 36.89%), spine/spinal column (54; 44.26%), upper limbs (42; 34.43%), and lower limb injuries (48; 39.34%) were frequent in trauma patients who fell from height. Thoracic injuries were most frequent in road traffic accidents (222; 47.74%). This was followed by upper limb injuries (200; 43.01%). Overall, amongst the body regions, head was the most commonly injured (48; 45.40%), followed by lower limbs (377; 35.37%) and thorax (299; 28.05%) [Table 8].

Table 8.

Patterns of Injuries in parallel to mechanisms of injury

In analyzing specific association between injury mechanisms and sites of injury, we identified several associations that were highly significant. Patients who sustained injuries as a result of road traffic accidents were associated with more than three times increased risk of injuries to the face (OR = 3.65, P = 0.0000001), chest (OR = 6.22, P = 0.00000001), abdomen (OR = 5.15, P = 0.00000001), and upper limbs (OR = 4.91, P = 0.00000001). Patients who suffered injuries following falls from heights were four times more prone to pelvic (OR = 4.4, P = 0.00000001) and spinal injuries (OR = 3.95, P = 0.00000001). Those who had falls on same level were 1.5 times more likely to suffer from head injuries (OR = 1.5, P = 0.001) and less likely to show injuries to face (OR = 0.24, P = 0.00000001), thorax (OR = 0.09, P = 0.00000001), abdomen (OR = 0.02, P = 0.00000001), pelvis (OR = 0.2, P = 0.00000001), and upper limbs (OR = 0.12, P = 0.00000001) [Table 8].

DISCUSSION

We found that the preponderance of males among those injured is consistent with data from several studies.[7,8,9,10,11] Similar to our findings, both fatal and non-fatal injuries occurred more frequently among males than females. More than half of all trauma cases in our study (59.4%) were male patients. Several possible reasons for this had been suggested including greater number of vehicles driven by males and more participation in high risk activities, i.e. sports and work.[7]

Our study revealed that Malays had the highest ethnic-specific traumatic injury rates (103.94 vs. 86.66 among Indians vs. 67.59 among Chinese per 100,000 populations). In our study, motorcyclists were the most vulnerable group of road users. We hypothesize that Malays highly represented this vulnerable group. Lateef in a prospective study of 1809 motorcyclists that presented to an Accident and Emergency Department between 2000 and 2001 revealed a proportionately higher presentation of Malays as compared to their proportion in the Singapore population.[12] Similar findings were reported in a study done by Wong et al.[13]

The predominant mechanism of injury was non-penetrating or blunt injury (98.13%). Our finding is somewhat similar to the studies done by Alexandrescu et al. and Padalino et al., in which penetrating injury was observed only in almost 5% of all trauma cases in the Europe and United Kingdom.[14,15] In some analyses in the United States, injuries such as gunshot or stab wounds accounted for a much higher proportion of penetrating trauma.[16,17] This variation could be due to the strict firearm control laws in Singapore as compared to the more liberal gun control legislation in the United States.

Our study revealed that falls (both same level falls and falls from height) were the most common cause of admission to the A&E, followed by road traffic accidents. Studies done by Moini et al. revealed similar findings.[18] Falls, including same level falls, were the most common mechanism of injury in the elderly, and falling down while standing or walking was common in old age.[19]

Motor vehicle accidents are among the ten leading causes of death and disability worldwide and have emerged as a serious public health concern.[20] It has been stipulated that transport-related injuries were among the leading causes of more severe injuries, particularly in the urban environment.[21] Our findings indicated that the most vulnerable road users were motorcyclists (283; 60.86%). This is consistent with the studies done by Phillipo et al. and Leong et al.[22,23] In Singapore, motorcyclists and their pillion riders continue to be a cause for concern. Despite the drop in the number of fatal and injury accidents (from 7,926 cases in 2011 to 7,168 cases in 2012), there is still a significant number of road traffic deaths. Recent implementations by the traffic police include inculcating safe riding behavior through the strategic enforcement teams as well as revisions made to the theory test structure for learner riders.[24]

Trauma results in severe life- and limb-threatening injuries. Our findings revealed that regardless of the mechanism of injury, injuries involving head, lower limbs, thorax, upper limbs, and spine/spinal column predominate in most trauma patients. The pattern of injuries observed in parallel to mechanisms of injury was not uncommon. In our study, patients who sustained injuries as a result of road traffic accidents were associated with more than three times increased risk of injuries to the face, chest, abdomen, and upper limb. This is somewhat similar to a study done in United Kingdom, which found that majority of the injuries sustained involved the upper parts of the body including head, face, neck, and thorax.[25] Patients who suffered injuries following falls from heights were more prone to pelvic and spinal injuries. Similarly, Hahn, et al. reported that the most common injuries were fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine with the incidence of thoracic and pelvic injuries increased following falls from greater heights of more than 7 meters.[26]

Consistent with our study, head has been reported to be the most injured region in the geriatric population.[19,27] The geriatric population was arbitrarily defined as comprising patients aged 65 or older.[19,27] Elderly patients fare worse than their younger counterparts because of the loss of physiologic reserve secondary to the ageing process, compounded with the burden of co-morbidities and pre-existing conditions.[28] From our observations, the elderly population has significantly greater number of falls from the same level (mean age 68.99 ± 16.66) of fairly significant severity (mean ISS 13.9 ± 7.51). This indicates a specific problem area where the elderly are particularly vulnerable to falls. Implementation of geriatric trauma programs and a more aggressive approach to elderly trauma patients is required in an effort to improve outcomes of geriatric trauma victims. Based on the injuries and areas sustained, there should also be greater focus in advancing neurosurgical and thoracic care.

Our study showed that there was no association with after-hours admission (P = 0.48). Of interest, one study had indicated that attending surgeons made 25% fewer cognitive errors than trainees during visio-haptic simulations to test realistic trauma interactions during fatigue conditions.[29] In our hospital, all radiological investigations, specialist consultations, and surgical procedures are available upon request 24 hours, 7 days of the week. Our CT scanners which are strategically located next to the trauma resuscitation rooms have enabled faster imaging acquirement and may in turn lead to quicker definitive decisions. A final consideration from a staffing perspective is that at least one experienced emergency department physician and a senior nurse attend to all initial trauma resuscitations 24 hours a day.

LIMITATIONS

Our current limitation is that we have not benchmarked our findings with any national standard. It would be interesting to compare our current findings over time as we continue to develop our trauma care.

CONCLUSION

Our study has addressed the epidemiology of trauma in an acute hospital in Singapore. Falls and road traffic accidents were the leading causes of injury; with traffic injuries being the leading cause among the younger group and falls among the relatively older population. There is a need to address the issues of injury control and prevention in these areas. Future studies could include the surveillance of all injured patients to identify high-risk groups, injury trends, and outcomes of preventive strategies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO.int. World Health Organization. [Lastupdated on 2013 Mar and accessed on 2013 Nov 9]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/injuries/about/en/index.html .

- 2.Ong A, Iau PT, Yeo AW, Koh MP, Lau G. Victims of falls from a height surviving to hospital admission in two Singapore hospitals. Med Sci Law. 2004;44:201–6. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.44.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine (AAAM) International Injury Scaling Committee (IISC): Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS)© 2005 Update 2008.

- 4.Pohlman TH, Bjerke HS, Offner P. Trauma scoring systems. [Last accessed on Nov 9]. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/434076-overview .

- 5.Schulter PJ. The Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) revised. Injury. 2011;42:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singstat.gov.sg. Singapore: Department of Statistics Singapore. [Last accessed on Nov 9]. Available from: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/Publications/publications_and_papers/cop2010/census10_stat_release3.html .

- 7.WHO.int. World Health Organization. [Last accessed on Nov 9]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs358/en/index.html .

- 8.Laupland KB, Kortbeek JB, Findlay C, Hameed SM. A population-based assessment of major trauma in a large Canadian region. Am J Surg. 2005;189:571–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moshiro C, Ivar H, Anne NA, Philip S, Yusuf H, Gunnar K. Injury morbidity in an urban and a rural area in Tanzania: An epidemiological survey. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olawale OA, Owoaje ET. Incidence and pattern of injuries among residents of a rural area in South-Western Nigeria: A community-based study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zargar M, Modaghegh MH, Rezaishiraz H. Urban injuries in Tehran: Demography of trauma patients and evaluation of trauma care. Injury. 2001;32:613–7. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(01)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lateef F. Riding motorcycles: Is it a lower limb hazard? Singapore Med J. 2002;43:566–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong TW, Phoon WO, Lee J, Yiu IP, Fung KP, Smith G. Motorcyclist traffic accidents and risk factors: A Singapore study. Asia Pac J Public Health. 1990;4:34–8. doi: 10.1177/101053959000400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexandrescu R, O’Brien SJ, Lecky FE. A review of injury epidemiology in the UK and Europe: Some methodological considerations in constructing rates. BMC Public Health. 2002;9:226. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padalino P, Intelisano A, Traversone A, Marini AM, Castellotti N, Spagnoli D, et al. Analysis of quality in a first level trauma center in Milan, Italy. Ann ItalChir. 2006;77:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, Moser KS, Brennan R, Read RA, et al. Epidemiology of trauma deaths: A reassessment. J Trauma. 1995;38:185–93. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199502000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shackford SR, Mackersie RC, Holbrook TL, Davis JW, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, Hoyt DB, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic death. A population-based analysis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:571–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170107016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moini M, Rezaishiraz H, Zafarghandi MR. Characteristics and outcome of injured patients treated in urban trauma centers in Iran. J Trauma. 2000;48:503–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200003000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterling DA, O’Connor JA, Bonadies J. Geriatric falls: Injury severity is high and disproportionate to mechanism. J Trauma. 2001;50:116–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mock CN, Abantanga F, Cummings P, Koepsell TD. Incidence and outcome of injury in Ghana: A community-based survey. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:955–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leong MK, Mujumdar S, Raman L, Lim YH, Chao TC, Anantharaman V. Injury related deaths in Singapore. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2003;10:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillipo LC, Joseph BM, Ramesh MD, Nkinda M, Isdori HN, Alphonce BC, et al. Injury characteristics and outcome of road traffic crash victims at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2012;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SPF.gov.sg. Singapore Police Force. [Last accessed on Nov 9]. Available from: http://www.spf.gov.sg/stats/traf2012_increase.htm .

- 25.Bradbury A, Robertson C. Prospective audit of the pattern, severity and circumstances of injury sustained by vehicle occupants as a result of road traffic accidents. Arch Emerg Med. 1992;10:15–23. doi: 10.1136/emj.10.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahn MP, Richter D, Ostermann PA, Muhr G. Injury pattern after fall from great height. An analysis of 101 cases. Unfallchirurg. 1995;98:609–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergeron E, Clement J, Lavoie A, Ratte S, Bamvita JM, Aumont F, et al. A simple fall in the elderly: Not so simple. J Trauma. 2006;60:268–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197651.00482.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iaria M, Surleti S, Fama F, Villari SA, Gioffre-Florio M. Epidemiology and outcome of multiple trauma in the elderly population in a tertiary care hospital in southern Italy (Meeting abstract) BMCGeriatr. 2009;9(Suppl 1):A69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerdes J, Kahol K, Smith M, Leyba MJ, Ferrara JJ. Jack Barney award: The effect of fatigue on cognitive and psychomotor skills of trauma residents and attending surgeons. Am J Surg. 2008;196:813–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]