Abstract

Background:

Risk-adjusted mortality is widely used to benchmark trauma center care. Patients presenting with isolated hip fractures (IHFs) are usually excluded from these evaluations. However, there is no standardized definition of an IHF. We aimed to evaluate whether there is consensus on the definition of an IHF used as an exclusion criterion in studies evaluating the performance of trauma centers in terms of mortality.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of observational studies. We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, BIOSIS, The Cochrane Library, CINAHL, TRIP Database, and PROQUEST for cohort studies that presented data on mortality to assess the performance of trauma centers and excluded IHF. A standardized, piloted data abstraction form was used to extract data on study settings, IHF definitions and methodological quality of included studies. Consensus was considered to be reached if more than 50% of studies used the same definition of IHF.

Results:

We identified 8,506 studies of which 11 were eligible for inclusion. Only two studies (18%) used the same definition of an IHF. Three (27%) used a definition based on Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) Codes and five (45%) on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. Four (36%) studies had inclusion criteria based on age, five (45%) on secondary injuries, and four (36%) on the mechanism of injury. Eight studies (73%) had good overall methodological quality.

Conclusions:

We observed important heterogeneity in the definition of an IHF used as an exclusion criterion in studies evaluating the performance of trauma centers. Consensus on a standardized definition is needed to improve the validity of evaluations of the quality of trauma care.

Keywords: Benchmarking, consensus, definition, isolated hip fractures, mortality, systematic review, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic injuries represent the first cause of death in North Americans aged less than 45 years.[1] The financial impact of injuries in the United States was estimated at 80.2 billion in 2000, for a deficit of 326 billion dollars in productivity.[2,3] The evaluation of trauma center performance to improve the quality and efficiency of trauma care is therefore of crucial importance.

The evaluation of trauma center performance is widely based on estimates of risk-adjusted mortality.[4] The effectiveness and validity of performance evaluations depend partly on a clear, standardized definition of the target population. Patients with isolated hip fracture (IHF) are usually excluded from trauma performance evaluations, as such injuries are considered a marker of chronic disease rather than a traumatic injury.[5] IHF can be defined according to diagnostic codes (Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD)), the presence or severity of concomitant injuries, and additional criteria including age and injury mechanism. Lack of consensus on an appropriate definition may compromise the validity and comparability of trauma system performance evaluations.[5]

The aim of our study is to evaluate whether there is consensus on the definition of an IHF used as an exclusion criterion for trauma center performance evaluations based on patient mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a systematic review of observational studies designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. We systematically searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, BIOSIS, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, TRIP, and PROQUEST electronic databases.

Search strategy

We constructed our search strategy using combinations of keywords, MeSH (Medline) and Emtree (EMBASE) from three domains: i) Trauma, ii) performance/quality, and iii) mortality (see appendix 1). The search strategy was first developed for Medline and then adapted for other databases. No restriction based on language or year was applied.

Study selection

Both prospective and retrospective cohort studies evaluating the performance of acute care hospitals for the treatment of global trauma populations (i.e., not specific pathologies) using mortality were considered for inclusion. We then selected studies excluding patients with an IHF for the review. Performance evaluation was defined as a comparison of hospitals within a health care system, over time or to an external standard.

Duplicates were identified and eliminated using the EndNote software version X4 (Thomson Reuters, 2010) and manual screening. Two independent reviewers (JT and AB) evaluated citations identified in the systematic search for eligibility by screening titles, abstracts, and full publications. Disagreement on study eligibility was resolved by consensus and two other reviewers (LM and AFT) were involved when required. Inter-rater agreement was evaluated with kappa statistics on study eligibility. Articles written in a language other than English were translated.

Data abstraction

Data was abstracted by two independent reviewers using a standardized data extraction form piloted on a sample of five representative articles. The data abstraction form was designed to capture information on study setting and design, the study population, definitions of IHF (including diagnostic codes, age, mechanism of injury, and additional injuries), and methodological quality. The latter was evaluated using the following six elements adapted from Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines,[6] the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias[7] and Downs and Black checklist:[8]

Data quality assurance efforts reported,

Measures of variation provided (i.e., standard errors or confidence intervals),

risk adjustment performed,

Appropriate treatment of missing data,

Appropriate sample size, and

Sensitivity analyses reported.

Appropriate treatment of missing data implied that the proportion of missing data were reported and if more than 10% of subjects had missing data, multiple imputation techniques, and/or sensitivity analyses were used.[9] Adequate sample size was considered to be respected if at least 100 patients per hospital were available for analysis or if not, analysis strategies designed for low-volume centers (e.g., shrinkage techniques) were used.[4] Disagreement between reviewers on abstracted data was resolved by consensus or if necessary, consultation with two other reviewers.

Analyses

The definition used for an IHF was described in terms of ICD or AIS diagnostic codes and additional criteria including age, severity of concomitant injuries, and mechanism of injury. Consensus on the definition of IHF was considered to be reached if at least 50% of studies used the same definition according to Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria.[10] The quality of study methodology (risk of bias) was described by the proportion of studies adhering to each of six quality criteria. A study was considered to be at low risk of bias if it adhered to at least four out of six criteria.

RESULTS

Search results

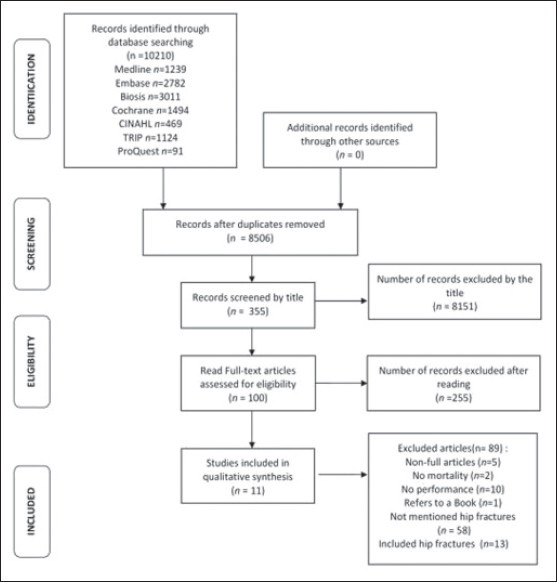

The search strategy identified 8,506 references of which 58 were selected for final review because they evaluated hospital performance on general trauma populations using mortality data [Figure 1]. Of these, 11 (19%) reported that they excluded patients with IHF and were therefore included in our study.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]

Figure 1.

Selection of articles for review

Study characteristics

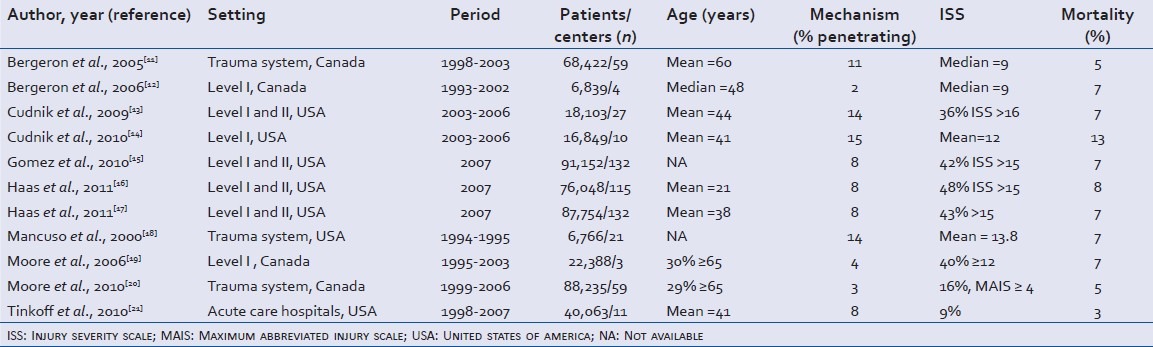

Included studies were conducted in Canada (n = 5)[11,12,17,18,19,20] or in the United States (n = 6)[13,14,15,16,18,21] [Table 1]. All were retrospective cohort studies published in English between 1993 and 2007. Despite the fact that all studies were performed in general trauma populations, inclusion/exclusion criteria varied across studies. Some studies used inclusion criteria based on traumatic injury;[11,12,18,21] whereas, others added criteria based on injury severity,[15,16,17] transfer[11,12,18,20,21,22] or diagnostic codes.[12,13,14,18] Common exclusion criteria other than IHF included death on arrival and poisoning/suffocation/drowning.

Table 1.

Description of included studies

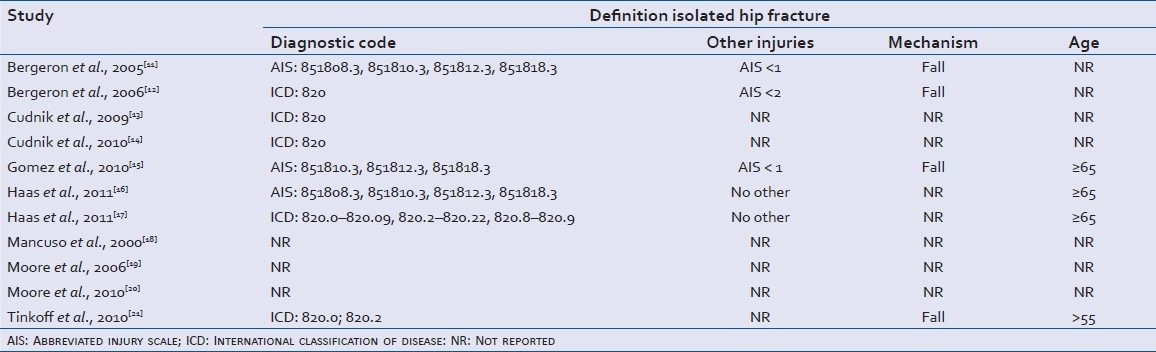

Definition of IHFs

Three studies did not report any definition of an IHF[18,19,20] [Table 2]. Only two studies (18%) used the same definition of an IHF and these studies were conducted by the same first author.[13,14] Five studies used ICD codes[12,13,14,16,21] and three used AIS codes[11,15,17] to define an IHF.[11,16] Five studies also included a criterion based on secondary injuries,[11,12,15,16,17] four used a criterion based on mechanism of injury,[11,12,15,21] and four studies used a criterion based on patient's age.[15,16,17,21] Overall, one study used all four criteria (diagnostic code, secondary injury, mechanism, and age) to define IHF,[15] five studies used three criteria[11,12,16,17,21] and two studies used one criterion in their definition.[13,14]

Table 2.

Definitions used for isolated hip fracture

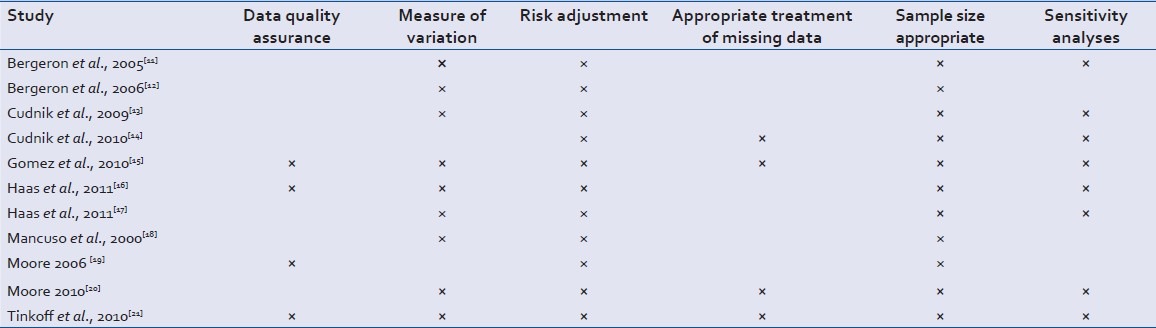

Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

Eight studies (73%) were considered to be of good methodological quality, because they respected at least four out of six criteria[11,13,14,15,16,17,20,21] [Table 3]. Nine studies reported variation measures for performance indices,[11,12,13,15,16,17,18,20,21] all studies used risk adjustment, and four studies reported using data quality assurance.[15,16,19,21] Eight studies provided information on missing data and addressed this problem by using multiple imputation.[14,15,20,21] However, three studies used single imputation techniques that do not account for the uncertainty surrounding missing values (leads to variance underestimation),[16,17] and four studies excluded variables with missing data from multivariable analyses.[14,15,20,21] Finally, eight studies conducted sensitivity analyses[12,13,14,15,16,17,20,21] and five studies reported having obtained research ethics board approval.[11,14,15,17,20]

Table 3.

Methodological quality of included studies

DISCUSSION

We did not observe consensus on the definition of IHF used as an exclusion criterion for trauma center performance evaluations based on mortality. Only two studies used the same definition of an IHF.[13,14] In addition, these two studies were based on a single diagnostic ICD code and were from the same group of researchers. Diagnostic codes (ICD or AIS) and additional criteria based on secondary injuries, mechanism of injury, and age all varied across studies. Overall, the methodological quality of included studies was high.

IHF represent up to 47% of injury admissions in patients aged 65 years or over and this proportion is increasing rapidly.[23] Patients with IHF significantly differ from other trauma patients for several reasons:

IHF is frequently the consequence of a chronic disease rather than a trauma per se,

They typically have higher resource use and worse outcomes despite lower injury severity,[11]

They often present with important comorbidities,

They are often treated outside the trauma system which leads to incomplete case capture in trauma registries, and

According to the National Trauma Data Standard, IHF should be included in trauma registries.[24]

However, 48% of trauma centers that contribute to the National Trauma Data Bank exclude patients with IHF from their trauma registries.[24] Despite the inclusion of IHF in trauma registries, the question of whether they should be included in performance evaluations remains controversial.[15] In this systematic review, we observed that patients with IHF were excluded from 20% of studies evaluating the performance of trauma centers in terms of mortality. The influence of including/excluding IHF on trauma center performance results is well documented. In 2010, Gomez and colleagues reported that more than three-quarters (78%) of centers changed their rank after patients with IHF were excluded from trauma center performance analyses.[15] In addition, Bergeron and colleagues observed that the inclusion/exclusion of IHF from trauma populations had an important impact on the evaluation of patient outcome and resource use.[12] Therefore, if IHF are not excluded from performance evaluations, they should certainly be evaluated separately. If they are to be excluded or separated in trauma center benchmarking activities, identifying these cases according to a standard definition is of great importance. This study shows that at present, no consensus on such a definition exists. These results are consistent with previous studies that have observed variations in the definition of same-level falls and age cut-offs for IHF.[24,25] Indeed, a survey among trauma registrars reported that in 18 different states, six different definitions of same-level falls were used as trauma registry exclusion criteria with varying age cutoffs and ICD-9 codes.[25] Hospitals contributing to the National Trauma Data Bank also use different age cutoffs to define IHF.[24]

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, despite the exhaustiveness of our search strategy and good inter-rater reliability on study inclusion, we might have missed some studies. Furthermore, we did not include studies that did not provide any information on exclusion or inclusion of patients with IHF. This may have led us to miss some definitions of IHF. However, this is unlikely to have affected the observed lack of consensus across studies. Second, several studies did not report information on methodological quality criteria. Lack of information was assumed to mean that they did not meet the criteria and may have led to an underestimation of methodological quality. However, adequate reporting of important information is a reflection of study quality.[6]

CONCLUSION

In this systematic review, we observed no consensus on the definition of IHF used as an exclusion criterion in studies evaluating the performance of trauma centers in terms of mortality. This lack of standardization may compromise the validity of trauma center benchmarking. It is thus important for future studies to assess the impact of the definition of IHF on the results of performance evaluations. In the event that significant changes are observed, an effort to reach expert consensus on a standardized definition of IHF must be made.

Appendix: 1. Medline search strategy

Trauma $. mp.

Injur$. tw.

Exp “Wounds and Injuries”/

1 or 2 or 3

Exp Quality Indicators, Health Care/

Quality Assurance, Health Care/

Benchmarking/

Total Quality Management/

“Health care quality, access, and evaluation”/

((Quality or process) adj2 (measure$ or indicator? Or compar*)). tw.

(Quality adj2 (assurance? Or evaluation$ or control$ or assessment$)). tw.

(Best practi?e?). tw.

Benchmark*. tw.

(Performance $ adj2 (improvement? Or evaluation? or measur$ Or assessment? Or compar*)). tw.

(Audit filter?). tw.

((Trauma* or surg$) adj audit?). tw.

“Risk adjusted scor$”.tw.

Health service* evaluation*. tw.

5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18

((Treatment? or assessment) adj2 outcome$). tw.

“Outcome assessment (health care)”/

Mortality.tw.

Mortality/

“Cause of death”/

Fatal outcome/

Hospital mortality/

Survival rate/

Death

Death/

Asphyxia/

Brain death/

Death, sudden/

Death, sudden, cardiac/

Discharge status

Patient Discharge/sn, mt, st, td [Statistics & Numerical Data, Methods, Standards, Trends]

Survival

Survival analysis/ or kaplan-meier estimate/ or proportional hazards models/

Survival/sn [Statistics & Numerical Data]

20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35v 36 or 37 or 38

4 AND 19 AND 39

Exp animals/not humans.sh.

40 not 41

Footnotes

Source of Support: The Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, the Fondation de Recherche en Santé du Québec (project #RC2-1460-05), and the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (LM is a recipient of a new investigator award).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Center for Disease Control. Cost of injury. 2007. [Last accessed on 2013 June 6]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/Cost_of_Injury.htm .

- 2.Sunnybrook Research Institute. The enormous human and financial cost of trauma. 2007. [Last accessed on 2013 April 16]. Available from: http://www.swri.ca/programs/trauma .

- 3.Finkelstein EA, Corso PS, Miller TR. The incidence and economic burden of injury in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006. [Last accessed on 2013 May 26]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/CostBook/Economic_Burden_of_Injury.htm .

- 4.Iezzoni L. Risk adjustment for measuring health care outcomes. 3rd ed. Chicago: Health Administration Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Surgeons. National Trauma Data Bank report. 2011. [Last accessed on 2013 April 27]. Available from: http://www.facs.org/trauma/ntdb.html .

- 6.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. Cochrane Bias Methods Group, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allison PD. Missing Data Thousand. Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Dellinger P, Schünemann H, Levy MM, Kunz R, et al. GRADE Working Group. Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. BMJ. 2008;377:a744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Belcaid A, Ratte S, Clas D. Should patients with Isolated hip fractures be included in trauma registries? J Trauma. 2005;58:793–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000158245.23772.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Moore L, Bamvita JM, Ratte S, Clas D. Paying the price of excluding patients from a trauma registry. J Trauma. 2006;60:300–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197393.64678.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cudnik MT, Newgard CD, Sayre MR, Steinberg SM. Level I versus Level II trauma centers: An outcomes-based assessment. J Trauma. 2009;66:1321–6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181929e2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cudnik MT, Sayre MR, Hiestand B, Steinberg SM. Are all trauma centers created equally. A statewide analysis? Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:701–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez D, Haas B, Hemmila M, Pasquale M, Goble S, Neal M, et al. Hips can lie: Impact of excluding isolated hip fractures on external benchmarking of trauma center performance. J Trauma. 2010;69:1037–41. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f65387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas B, Gomez D, Hemmila MR, Nathens AB. Prevention of complications and successful rescue of patients with serious complications: Characteristics of high-performing trauma centers. J Trauma. 2011;70:575–82. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820e75a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas B, Gomez D, Xiong W, Ahmed N, Nathens AB. External benchmarking of trauma center performance: Have we forgotten our elders? Ann Surg. 2011;253:144–50. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f9be97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mancuso C, Barnoski A, Tinnell C, Fallon W., Jr Using Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS)-based analysis in the development of regional risk adjustment tools to trend quality in a voluntary trauma system: The experience of the Trauma Foundation of Northeast Ohio. J Trauma. 2000;48:629–34. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200004000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore L, Lavoie A, Camden S, Le Sage N, Sampalis JS, Bergeron E, et al. Statistical validation of the Glasgow Coma Score. J Trauma. 2006;60:1238–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195593.60245.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore L, Hanley JA, Turgeon AF, Lavoie A, Eric B. A new method for evaluating trauma centre outcome performance: TRAM-adjusted mortality estimates. Ann Surg. 2010;251:952–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d97589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinkoff GH, Reed JF, 3rd, Megargel R, Alexander EL, 3rd, Murphy S, Jones MS. Delaware's inclusive trauma system : Impact on mortality. J Trauma. 2010;69:245–52. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e493b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore L, Lavoie A, LeSage N, Abdous B, Bergeron E, Liberman M, et al. Statistical validation of the Revised Trauma Score. J Trauma. 2006;60:305–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000200840.89685.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark DE, DeLorenzo MA, Lucas FL, Wennberg DE. Epidemiology and short-term outcomes of injured medicare patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2023–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Surgeons. National Trauma Data Bank user manual. Version 7.2. 2009. [Last accessed on 2013 Sept 26]. Available from: http://www.facs.org/trauma/ntdb/pdf/usermanual72.pdf .

- 25.Mann NC, Guice K, Cassidy L, Wright D, Koury J. Are statewide trauma registries comparable. Reaching for a national trauma dataset? Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:946–53. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]